|

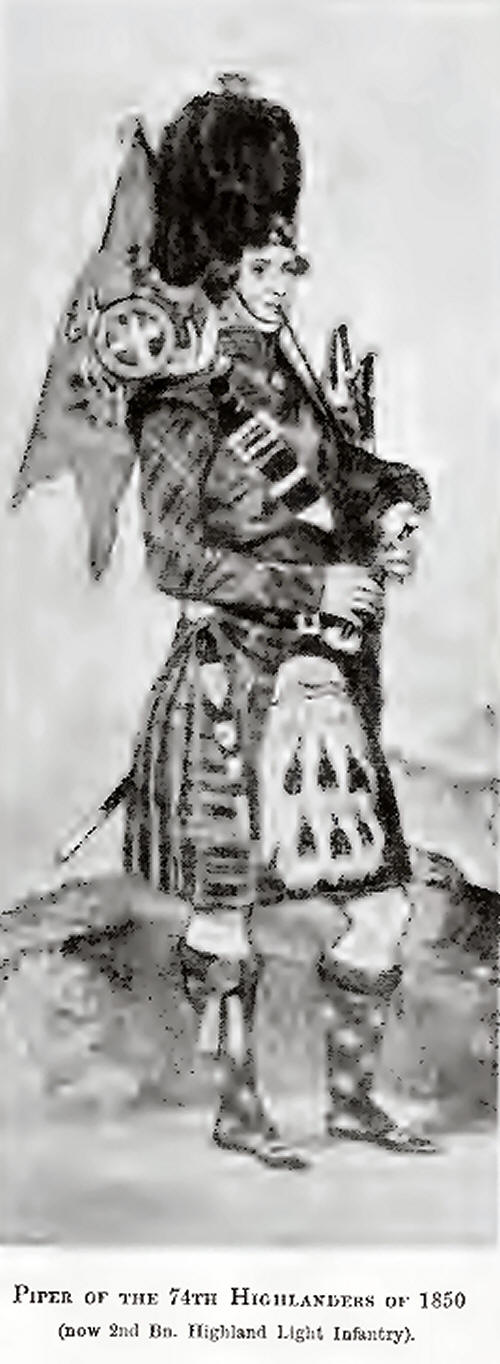

PIPERS OF THE HIGHLAND

LIGHT INFANTRY

Possessors of more battle

honours than any other Scots regiment, the Highland Light Infantry owe

much to their pipers. Long years before 1881, when the 74th Highlanders

were added as their 2nd Battalion, the pipers had materially assisted to

make the high reputation of the regiment. The 71st, or 1st Battalion,

had been raised in 1777 by John (Mackenzie) Lord MacLeod, eldest son of

the Third Earl of Cromartie, who had been “out in the Forty-five.”

Mustering at Elgin the regiment, comprising 681 Highlanders and 260

Lowlanders, were sent to India to repel the French and natives who were

then attacking the British settlements. After a weary voyage which

lasted twelve months they were disembarked at Madras and very quickly

had the misfortune to be too near an ammunition wagon which had

exploded, just as they were going into action. Several officers and men

were wounded and made prisoners by the large army of Hyder Ali, one of

the 71st’s officers being Captain Baird who was later to attain to much

fame as Lieut.-General Sir David Baird and of whose capture Sir Walter

Scott used to relate the following story. Baird’s mother, on being

informed that her son had been chained to another officer like all those

who had been in captured, ejaculated: “Lord peety the chiel wha’s

chained to oor Davie!”

That indignity was, however, spared Captain Baird, who was badly wounded

and whose services were in consequence lost to his regiment for some

weeks.

It was the battle of Porto Novo, 1st July 1781, which introduced the

pipers of the 71st to the admiring notice of soldiers far and wide. The

7lst, the only white battalion engaged, held the post of honour on the

extreme right of the first line. The whole force under Sir Eyre Coote

numbered but 8000; while the enemy had 25 battalions of Infantry, 400

Europeans, and about 45,000 Cavalrymen; and more than 100,000 matchlock

men and 47 cannon.

The position looked hopeless for the small body under Sir Eyre Coote.

All the brunt was on the Scots, everything depended on them, and that

seemed to be realised not only by the commander-in-chief but by one of

the pipers who accompanied the 71st. For eight hours the fight went on

and all the time that piper kept playing all that he knew of battle

tunes. The 71st put up their hardest and best and, surprising as it must

appear, actually won the day.

What the men and their officers actually thought about the piper one

cannot tell, but they must all have felt considerably astonished and

delighted when, at the close, Sir Eyre Coote rode up to the piper, shook

him heartily by the hand, “Well done, gallant fellow, you shall have a

silver set of pipes for this!” The promise was kept and the pipes are to

this day an heirloom at Headquarters of the 1st Battalion of the

regiment.

One engagement after another found the 71st and their pipers achieving

brilliant victories until the whole series terminated in favour of

British arms at Seringapatam in 1799. Then the 71st was sent off to

fight the Dutch in South Africa, thence to South America where the

fighting was still against the Napoleonic regime.

There, too, the pipers proved of value to their friends. One soldier

whose term of service had expired, confided to a comrade his intention

to remain in that sunny land; the comrade said nothing—merely hummed a

pipe tune, “Lochaber No More.” It was enough; “Ach, no, I could not . .

. no, I must go back.”

After the street fighting in Buenos Ayres in 1806 the pipe-major

discovered that he had lost his pipe banner. How it had gone, whether by

capture or by his own carelessness, none could say. The loss was soon

forgotten in the press of other affairs. Judge, then, the surprise of

the successors of these officers and pipers when, eighty years later,

they were informed that the old pipe banner had been all that time a

treasured relic in an old family in Chile and that it was to be restored

to the regiment. The circumstances were these: In 1882 Sir John Drummond

Hay, H.M. Charge d’Affaires at Valparaiso, wrote to Her Majesty Queen

Victoria stating that Santiago D. Lorca, Admiral of the Chilian Navy,

had a British banner which had been in the possession of his family

since the days of his grandfather, who had enjoined his sons to treasure

it until circumstances should permit of its safe return to the British

nation; and that he now proposed to hand it over to the Charge

d’Affaires. This was the long missing pipe banner of the 71st. Her

Majesty, regarding it as valuable as a regimental colour, gave order for

a warship to be sent for the delivery of the precious relic. That was

done, and the Queen having inspected it, handed it to the

representatives of the 71st, who placed it in their Headquarters, where

it still reposes, showing a thistle and rose, the emblems of the

regiment, embroidered on a field of crimson silk fringed with gold.

[Another pipe banner of the 71st still bangs in Santo Domingo Church,

Buenos Ayres,]

If the 71st won fame by its piper in India it was destined to achieve

more fame in the Peninsular War by the valour of another piper. At the

battle of Vimiera, 21st August 1808, Piper George Clark set the example

so often followed in later actions, of continuing to play, in spite of

severe wounds, the regimental charging tune, “Up and waur them a’,

Willie.” Clark played when he fell wounded and played for some time, the

while his comrades, animated by his play, fought on. Officers and men

feted the wounded piper and would have urged the Authorities to bestow a

decoration on him had such things been customary then. They did their

best, however, for they told of the heroism of Clark, and that was

lauded by civilians at home to so great an extent, that on the return of

the regiment to Scotland, the Highland Society held a reception in

honour of Piper Clark and awarded him a gold medal and a set of pipes.

Moreover, when their piping competition was about to be held they

dissuaded him from competing, probably because they did not wish to see

him second to any; and having awarded him a special gold medal,

appointed him piper to the Society.

In 1813 the pipers of the 71st were at Vittoria, where they played

“Johnny Cope” in the brilliant uphill charge against the French — a fact

alluded to by a Forfarshire poet, William Glen, one of whose stanzas

runs as follows:—

If e’er they meet their worthy king,

Let them dance roun’ him in a ring,

And some Scots piper play the spring

He blew them at Vittoria.

The renown of the regiment which had relied so much on the prowess of

its pipers had more than a transitory effect on its fortunes. Because of

its brilliant conduct in the various actions in the Peninsula, the 71st

was, in 1809, promoted to be a Light Infantry regiment which, among

other details, meant an alteration in dress and accoutrements. Light

Infantry corps were not as other regiments, but wore a distinctive

uniform which permitted of greater freedom in their quick movements and

skirmishing duties; and they had a bugle band to cheer them on their

way. These were very fine for ordinary regiments of Foot, but hardly

good enough for a Highland regiment that prided itself on its

picturesque dress and its own form of musical instrument. Accordingly

Colonel — later General — Sir Denis Pack appealed to Headquarters that

the 71st might be allowed to retain the title of “Highland” before the

new designation “Light Infantry,” and that it might continue to wear

“such parts of the national dress as might not be inconsistent with

their duties as a light infantry corps, including the ‘bonnet cocked’”;

finally, he urged, “that they keep their pipers in all their customary

dress. It cannot be forgotten bow these pipers were obtained and how

constantly the regiment upheld its title to them. These are the

honourable characteristics alluded to, which must preserve to future

generations the precious remains of the old corps, and of which I feel

confident His Majesty never will have reason to deprive the 71st

Regiment.”

This eloquent appeal had the desired result. The letter of 12th April

1810, from Whitehall, contained an assent to all Colonel Pack’s

requests, and as the “71st Highland Light Infantry” it shared, with the

90th Perthshire Regiment—now 2nd Battn. Scottish Rifles — the

distinction of a Light Infantry regiment, and of being the only light

infantry corps in possession of pipers — all the other light infantry

corps being English. This right to pipers was confirmed in 1854 when

Headquarters permitted each Highland unit to have a pipe-major and five

pipers. Yet, here again, there continued for many years a difference

between the pipe band of the H.L.I. and that of every other regiment;

there were no drums in light infantry units and the H.L.I. carried on

without these great assets until 1905, when there was appointed a

pipe-major who, coming from the Seaforth Highlanders, deplored the lack

of the sheepskins. The officers acceded to the earnest representation of

Pipe-Major James Taylor by getting the necessary number of drums.

The pipers had then a long list of battle honours: Waterloo, Sebastopol,

the Indian Mutiny, Tel-el-kebir, Crete and South Africa, 1899-1902,

being the successors of the eighteenth century engagements. It was in

the last-named war that two pipers of the H.L.I., Pipe-Major Ross and

Piper J. M'Lellan, were both awarded the D.C.M. for conspicuous

gallantry in the battle of Magersfontein where, in the most exposed part

of the field, they played the regimental “Assembly” with such excellent

effect that the scattered soldiers were brought together. M‘Lellan was

poet and composer of several melodious tunes, one of which received —

while the battalion were stationed in Egypt — the name of “The Burning

Sands of Egypt,” and, after doing duty in South Africa as “The March to

Heilbron,” it was adapted to the words of a song which is yet popular:

“The Road to the Isles.” Such at least is the proud claim of the H.L.I.

Ihe 2nd Battn. the 74th Highlanders has an equally notable record of

distinguished pipers, the earliest noted of whom is George Maclachlan,

who was among the first to scale the twenty-foot-high wall at the siege

of Badajos. Several were killed in the attempt and many more were

wounded but Maclachlan escaped; only his bagpipe was hit just as he had

reached the top and had started “The Campbells are Cornin’.” Maclachlan

coolly sat on the ramparts, heedless of the bullets that went whizzing

past, repaired his bagpipe, tried it, and resumed his advance and the

stirring tune. It was he who averted disaster from his regiment at

Vittoria, where the 74th had gone to the rescue of the 88th Regiment.

The adjutant had tried in vain to recall his men; they heard him not.

Without direction of any kind Piper Maclaclilan promptly played the

“Assembly” while he stood by his officer’s side, and the men, hearing

the old, familiar notes, came towards him at the “double.”

That successful exhibition of native wit and initiative became the talk

of the officers and was reported to Headquarters; the grateful adjutant

promised the piper a reward of value, but alas! that promise could not

be redeemed, for Piper Maclaclilan shortly afterwards was killed in the

thick of battle.

In the Great War the Highland Light Infantry had all its nine “New Army”

battalions, six territorial and two regular battalions engaged in one or

other of the theatres of war; and in every unit the pipers were

conspicuous either as pipers, runners, ration and ammunition carriers,

stretcher-bearers, or with rifle and bombs.

The 2nd Battalion was the earliest in action. As part of the Second

Division it fought in all the actions from Mons to Festubert, December

1914. It was then that the 1st Battalion arrived from India. The pipers

of the 1st Battalion numbered twenty-eight, twenty-two of them being

“acting” pipers; the 2nd Battalion had a pipe

band of fifteen, of whom

nine were “acting” and accordingly these reverted to the ranks in

accordance with Army regulations. The six “full” pipers of the 2nd

Battalion — who became stretcher-bearers, and at times ammunition

carriers — were all casualties by the close of the year 1914, their

places being taken by pipers sent from the depot. Festubert accounted

for some severe losses to the pipers of the 1st Battalion — two were

badly wounded, two were captured, and the pipe-major and four of the

acting pipers killed in action. One piper—Morrison —was long remembered

for the gallant fight which he made against hopeless odds and for his

refusal to surrender to a number of Germans who surrounded him he fell

at last with seventeen bayonet wounds.

The shell-swept field of Richcbourg also forms one of the vivid memories

of the H.L.I. pipers, one of whom, Pipe-Sergeant Godsman, carried bombs

throughout the battle, to the surprise of his comrades who entertained

few hopes of his survival. The pipe-sergeant, however, did escape,

though wounded, and had the satisfaction later of learning that his

devotion to duty and disregard of danger had been recognised in the

award of the Cross of the Russian Order of St George, a distinction

shared by another piper.

The Territorial battalions began their war experience in Gallipoli,

where the casualties among the pipers were heavy in consequence of their

position at the head of their respective battalions. So great were these

casualties, that on the eve of evacuation of the peninsula, pipers could

not be obtained except after an exhaustive search among men in the

trenches who had not enlisted as pipers. The pipers who had played their

companies forward were in many cases found lying dead on the battlefield

with their pipes by their side.

Piper Kenneth M‘Lennan of the 7th Battn. H.L.I. was more fortunate,

though he had his pipes blown out of his hands by a shell in the action

of 12th July 1915 when he was at the head of his company; piping being

over he became stretcher-bearer, tended the wounded under heavy fire,

and had his gallant services recognised by the award of a D.C.M.

The pipers who had been found among the rank and file were formed into

one pipe band for the Division and were utilised for the marches through

Egypt and Palestine, their music being appreciated not only by the

Division but by all who were near enough to hear them. Men writing home

mention how the sound of the pipes reaching their ears over wide

expanses, seemed like a whiff from the homeland where they had thought

little of pipe music. These improvised pipers carried on until they were

brought to France where they became stretcher-bearers or runners, or

ammunition and ration carriers.

In the “Kitchener” battalions of the H.L.I. the pipers were at times

playing their companies into action, at other times they fought in the

ranks, and very often they were stretcher-bearers and runners. Young

Gilbert, the pipe-major of the 17th Battalion, was one of those who took

each of these duties in turn, and for a considerable time he was

actually Regimental Sergeant-Major. It was, however, for his work as a

runner from Headquarters to battalion lines that he received the

Military Medal.

In the Somme offensive of July 1916 the pipers were with the battalion

of the H.L.I. which penetrated farthest into the enemy lines. There

Piper Hugh MacArthur had been as a rifleman and at the close of the day

returned to Headquarters for rest. He was not long there when the

Headquarters Company was almost surrounded by German troops who were

strenuously bombing. Neighbouring battalions were being pressed back and

everything looked “black” for our troops. Piper MacArthur pondered the

situation and promptly decided that only a stirring air on the pipes

could have any chance of averting disaster. Accordingly he got his

pipes, stood on the top of a trench and played as loudly as he knew how,

with the anticipated result — the repulse of the enemy!

On the glad occasions of Divisional Games the pipers of the different

battalions proved their skill by winning prizes for pipe-playing. The

pipers of the 2nd Battalion won the first prize in 1917 for marches,

strathspeys, and reels, and the 7th (Territorial) Battalion were first

in 1919 in competitions open to Brigade, Division, and Army Corps.

A unique departure from the old Army pipers’ ways was made in

consequence of the American army’s entry into the War. Their authorities

had requested the services of some officers and non-commissioned

officers as instructors, and no one was surprised; but when they also

asked for the “loan” of pipers the request seemed odd. Pipers were sent

and those selected were from the 14th Battn. H.L.I. Very soon these

pipers learned to their considerable surprise that the gentlemen with

the nasal twang were not all so ignorant of pipe tunes and pipers’ ways

as they had imagined. After all it was not so surprising, for the Yankee

hat and the nasal twang often disguised the ubiquitous Scot. |