|

FOREWORD

By The Duke of Atholl, K.T., G.C.V.O., C.B.

Mr Charles A. Malcolm has

asked me to write an introduction to his book The Piper in Peace and

War. Every one who reads the book will admit that Mr Malcolm has taken

an extraordinary amount of pains to collect his data, and that he has

written a book which will be read with much interest by those who are

fond of the pipes.

Tradition, unless set

down on paper, is apt to become lost or inaccurate. It is well,

therefore, that these traditions should be handed down in writing by

those who are capable of doing so, and I think no one will deny Mr

Malcolm’s capability and zeal.

Probably there were never

more pipers in existence than there were during the Great War, and never

at any time were their services more appreciated. No good

pipe band ever belonged to a bad regiment, and to those who understand

the pipes

it is a simple thing to

judge of those who follow them. In times of peace the pipers keep the

men together. Every individual man in the regiment takes a pride in the

band because it is distinctive and of his own nation, proud and full of

courage, but not aggressive, sometimes sad but always appealing.

The wide extension of

pipe music in these days, when every mining village in the south of

Scotland and every tourist resort in the north has its local pipe band,

may have increased the number of pipers, but I doubt if it has improved

their quality. But few of the modern airs have the special character or

the distinction of the old music, and the old tunes, when played, have

little difficulty in holding their own. While it is everything to have

good band pipers in military units, the local bands are doing much to

eliminate the old individual player, who was a musician first and a

bandsman second. Some of the best pipers that I used to know in the old

days—men with beautiful fingering and who put their whole soul into a

piobaireachd— were indifferent players of marches. While the old airs

are not being lost, for they are written down, very few of the modern

pipers have a good repertory. Many of the best of them seem to have a

sort of musical circle, like that on a roulette table. You can pick any

number you like so long as it is shown on the wheel. These are their

competition tunes, but outside that you must not and cannot go.

Publishers, presumably for financial reasons, appear to be more

interested in publishing the new tunes than the old ones, and in pushing

their sale. The result is that many young pipers do not know the grand

old tunes, but are experts at inferior modern ones, and if, by chance,

one strikes their fancy, we hear that tune and no other till we are sick

to death of it The old tunes, in their names and characters, remind us

of our hills and glens, of our history, of brave men, of national sorrow

and of times of national joy. Can that be said of most of the new ones?

While we have splendid

pipe bands in the Army, they are bound, for purposes of playing

together, to be stereotyped. One always feels when they are playing that

the pipers have one eye on the Drum-Major in front and the other on the

Regimental Sergeant-Major behind. I remember one young regimental piper,

when checked for indifferent playing, saying “My thochts were on the

counter march.” Under such conditions, it is difficult to have one’s

mind up in the heavenly sphere of music.

We find the same thing in

Highland dancing, where large numbers are taught by the same instructor

at the same time. The boys at Scottish Institute Schools dance

beautifully. They all skip at the same time in the same way and to the

same height. As a gymnastic or ballet display it is fine. As Highland

dancing the soul and joy is gone out of it. When watching such displays

or competitions, I sometimes feel more joy in the one that has strayed

that in the ninety-nine that have not.

In other words, the

general extension of piping, while it may have done much to popularise

the instrument, has not improved things from a musical point of view,

and the efforts of those who love pipe music should be used towards

maintaining standard and character rather than in increasing numbers.

That Mr Malcolm should remind us, therefore, of the days that are gone

is all to our advantage.

ATHOLL.

September 1927.

PREFACE

It is not the purpose of

the writer to treat of the various forms of bagpipe used in the past by

the different nations of the world, but to trace as far as possible the

work in peace and war of the skilful and intrepid masters of the “great

war pipe of the north.”

It may be noted, however,

that the oldest memorial to a piper is not one to any distinguished

Highlander or Borderer, to a M'Crimmon, a M'Intyre, a Mackay, a

MacArthur, a Habbie Simpson, or a Hastie, but to an unknown Roman

legionary, a member of the Roman Army of Occupation in Britain. His

statue occupied a niche in the great Roman Wall from the Tyne to the

Solway. Though Time hasdealt gently with the effigies of this piper, it

is to be regretted that it has not left his pipes in such a state as to

enable us to trace the details of their construction. The bag is there,

but not the drones. Yet here is evidence, though all the historians are

silent on the point, that the legions of Cassar marched to the strains

of the pipes, and that the piper was a person of some consequence in the

great armies of Rome. It is strange to reflect that, just as in later

times the Scottish bagpipe has contributed to victory, so the armies of

Imperial Rome seem to have been led to conquest by pipe music.

This attempt to rescue

what might have been forgotten and to focus what has been stated in

various regimental records, newspapers, and public speeches, imperfect

as it is, would not have been possible but for the kindness of officers,

noncommissioned officers, and men of II.JI. Forces of Great Britain,

Ireland, and the Dominions overseas, whose names are too numerous to

mention; officials of the War Office, Public Record Office, and Canadian

Headquarters. In particular I owe thanks to Colonel John Murray, D.S.O.,

for many helpful suggestions and reports; to Major Ian II. Mackay-Scobie

who, besides revising proofs, lent prints and communicated numerous

interesting facts; and to Mr Kennedy Stewart, M.A., and my brother Mr

Peter Malcolm, M.A., for their labours in the revision and the

correction of the typescript and of the proofs of this book.

CONTENTS

PART I THE PIPER IN PEACE

AND WAR

I. (1) The Army and the

Piper

(2) Status of the Army Piper

II. The Piper in Barracks and Camp

III. The Bagpipe in Battle

IV. The Pipes in Strange Places

V. The Influence of the Pipes

VI. Pipe Music

PART II RECORDS OF THE

PIPERS

Scots Guards

Royal Scots

Royal Scots Fusiliers

King’s Own Scottish Borderers

Cameronians (Scottish Rifles)

Black Watch (Royal Highlanders)

Highland Light Infantry

Seaforth Highlanders

Gordon Highlanders

Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders

Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders

Lovat Scouts

Scottish Horse

London Scottish

Liverpool Scottish

Tyneside Scottish

Irish Regiments

Canadian Forces

Australian Forces

New Zealand Forces

South African Scottish

Royal Navy

PART III

Some Well-Known Army

Pipers

Note by the Earl of Dartmouth, K.C.B on the Picture at Patshull House

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

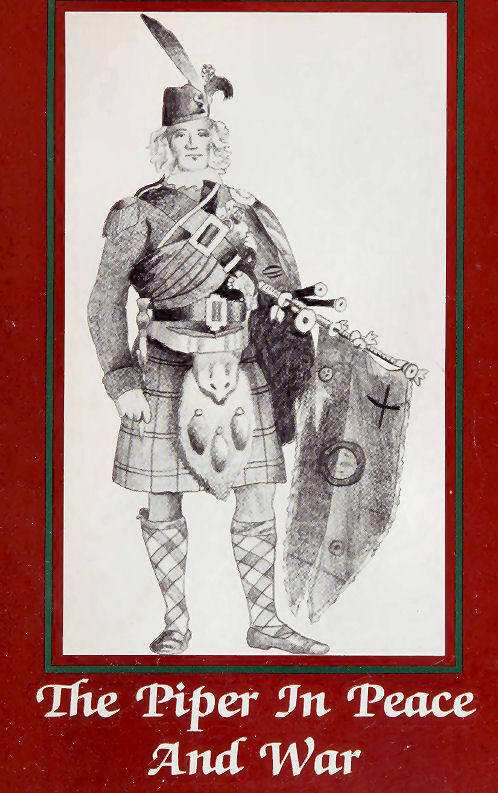

George Clark, the Piper

of Vimiera. From a print in the possession of Major Mackay-Scobie

Frontispiece

"Jock in the thick of it:

coming away from the Trenches.” From a drawing by Georges Scott By

permission of The Graphic

“The Piping Times of Peace.” From a picture by Fred Roe, R.I. By

permission of The Graphic

Piper Laidlaw outside the British Trench playing “Blue Bonnets over the

Border.” From a picture by S. Begg. By permission of the Illustrated

London News

Piper Donald MacDonald, 42nd Highlanders, 1743. By kind permission of H.

D. MacWilliam, Esq.

Piper of the 74th Highlanders of 1850 (now 2nd Bn. Highland Light

Infantry). From the Historical Record of the 74th Regiment (Highlanders)

The Irish Guards Pipers

The Mole of Tangier in 1684. From a picture by Stoop in the possession

of The Earl of Dartmouth

|