|

IN the last chapter we saw

how Leith at last freed herself from the shackles by which Edinburgh had

for so many long centuries restricted her from almost any share in the

shipping trade of her own harbour. But Edinburgh, in another way, still

continued to hamper Leith’s activities, for, from the closing years of

the fourteenth century, she began to have another hold on Leith which

tightened more and more as the years passed, and held her in an even more

galling bondage than that of being excluded from any share in the foreign

trade of her own harbour.

In being shut out from

engaging in the overseas trade of their own port Leithers were no worse

off than the inhabitants of other unfree ports throughout the land. The

Clyde burghs of Rutherglen, Renfrew, and Dumbarton did all they could to

hamper and impede the trade of the unfree town of Glasgow. But there the

jurisdiction of these royal burghs over Glasgow ended. They had no other

rights over the good folk of this unfree port, who in all other matters

were under the authority of their own overlord, the archbishop of the

cathedral.

The lot of those unfree

towns was happy compared with that of Leith. For not only did Edinburgh

own the harbour, and possess the sole right of carrying on all the

overseas trade of the port of Leith, but by purchasing the feudal rights

of the Logans and other superiors she gradually became overlord of nearly

the whole town as well, and thus exercised complete authority over its

inhabitants, and regulated all their doings. Leith was in the position of

a serf of which Edinburgh was the owner. Serfs had really no individual

rights, and therefore Leith as a town had none. Its inhabitants were for

this reason looked on as unfree. No other town in Scotland had the freedom

of its inhabitants so hampered and obstructed, or had its affairs so

completely subjected to the selfish interests of its overlord, as were

those of Leith.

From 1398 down to 1833,

when Leith was made a separate burgh by Act of Parliament, the

relationship between the two towns may be described as, on the one hand,

the most constant and jealous interference and control on the part of

Edinburgh to further what she considered her undoubted rights, and, on the

other hand, an equally constant evasion of this control on every possible

opportunity on the part of Leith. The Merchant Guild of Edinburgh, who

alone at this time, and for the next two hundred years, monopolized the

right to membership of the Town Council, thought, and no doubt rightly,

that they could enforce and maintain their trade privileges in Leith all

the more strongly if they, instead of the Logans, were the feudal

superiors of the town.

Gradually, therefore, the

whole of South Leith held by the Logans passed from the possession of the

barons of Restalrig into that of the wealthy and, if truth must be told,

somewhat proud and overbearing merchant burgesses of Edinburgh, who proved

very exacting overlords to the Leithers, just as they were somewhat

tyrannous and oppressive in their rule of all the inhabitants of Edinburgh

itself who were not fortunate enough to be members of the Merchant Guild,

and whom they jealously excluded from all share in the municipal

government of the city.

To the many restrictions

and prohibitions upon her freedom to trade abroad, dating from the

earliest years of her history—for Bruce’s famous charter only

confirmed what former kings had granted—we owe the origin of the

unfriendly feeling between the two towns. But to the irritating and

humiliating state of vassalage just described, much more than to Edinburgh’s

trading privileges as a royal burgh, is due that feeling of suspicion and

unfriendliness that still, to some extent, exists between the two towns.

The prolongation of this state of vassalage for so many years after the

growing commerce of the country had rendered the trading restrictions no

longer possible, added to and greatly intensified this unfriendly feeling.

The Town Council of

Edinburgh, then, gradually acquired complete control of Leith and all its

affairs. For this reason Leith never had a provost, magistrates, or town

council of her own until she became a parliamentary burgh under the Burgh

Reform Act in 1833. The records of the Town Council of Edinburgh form a

rich storehouse of the city’s history, and are valuable for the

information they give regarding the customs and social life of its

inhabitants in mediaeval times. Leith, on the other hand, having been an

unfree town right down to the early decades of the nineteenth century,

has, of course Town Council records from that time only, and thus what

would have proved a valuable source of her early history was never

written, and so we must look for it elsewhere. The loss from 1589 is

partially replaced by the records of the Sessions of South and North Leith

Parish Churches Of the former body, the two Edinburgh bailies—the Water

Bailie and his Deputy—charged with the control and supervision of South

Leith affairs, were members by virtue of their office.

The Session of the Parish

Church, aided by the two Edinburgh bailies, strange as it may seem to us

in our more democratic days, discharged many of the duties of a town

council, and for over two hundred years had a considerable share in the

management and direction of the public affairs of the town. Their records

have been published for the period 1588—1700, and are not surpassed in

the interest of their details by any similar publication for the same

period. Yet few Leithers have taken the trouble to read them, and still

fewer have thought them worthy of purchase. That seems altogether strange

in a town that has never lacked a vigorous spirit of local patriotism.

We have learned that from

the earliest days of their history, towns, like baronies, had their

overlords, who held absolute sway over them and their inhabitants. As they

grew in size towns became impatient of this rule, and wished to govern

themselves through their corporations, as our towns do today. Where the

king or some noble was overlord this freedom of self-government was not

very difficult to obtain, for kings and nobles were often in need of

money, and this need the towns under their rule were ever ready to supply

in return for a larger freedom. They would advance a goodly sum to a needy

king or baron in return for a document called a charter, in which the

privileges to be granted them were fully detailed. Step by step in this

way towns were constantly obtaining a larger measure of freedom until, as

in the case of royal burghs like Edinburgh, they finally obtained

self-government.

In many cases, as in that

of Edinburgh, this privilege of self-government was acquired at so early a

period that the charter by which it was granted has long ago disappeared.

The royal burghs grew to be the largest and most important towns in the

country, because they were allowed to develop freely without their

industrial activities being fettered in any way by the arbitrary rule of

some overlord. Baronial towns like Dalkeith were not quite so fortunate,

and towns like the Canongate, which belonged to the Church, were still

less so in their struggle for freedom, though continued for centuries, as

rich and powerful bodies like the abbot and monks of some wealthy abbey,

such as Holyrood, could not be induced to part with many of their powers

by offers of money, however large.

But the lot of Church towns

like the Canongate or Musselburgh was fortunate compared with that of

unhappy Leith. While it was not unusual in Italy during the Middle Ages to

find one town subject to another at least for a time, so far as its

outside relations were concerned, as Pisa and Lucca to Florence in the

early fourteenth century, yet such a servitude, except in the case of that

of Leith to Edinburgh, was unknown in Scotland. In being subject to

Edinburgh, Leith was the vassal of a wealthy city corporation, proud of

its possessions and privileges, whom no sum of money could tempt to part

with any one of them in the smallest degree. On the contrary, in order to

obtain more complete control of the harbour and its shipping, and to check

any attempt of the Leithers to evade her statutes and ordinances, or to

infringe her trade monopoly, it was to the interest of Edinburgh to

tighten by every means in her power, rather than to relax, her hold over

her unhappy vassal, and the most effective way of doing this was to obtain

possession of the town as well as of the harbour. This then became the

traditional policy of the Corporation of Edinburgh, and they spent large

sums of money in its pursuit.

The town of Leith in the

far-off times of which we are now speaking—the closing years of the

fourteenth century—was owned by three feudal superiors: the king, the

Laird of Restalrig, and the Abbot of Holyrood. Edinburgh’s first

possessions in Leith were, of course, those of the harbour and mills

gifted to her by royal charter at some period of that golden age of

Scotland’s history extending from the reign of David I. to the death of

Alexander III.—that is, between 1124 and 1286. Mills, owing to the large

revenue derived from them, were among the most valuable of an overlord’s

possessions. They were as prominent a feature in the Leith of the

fourteenth century as they are today, for both the Laird of Restalrig and

the Abbot of Holyrood had mills in Leith as well as the Town Council of

Edinburgh. No barony, indeed, was then without its mill. Though in later

years we find windmills as well, those in Leith at this time were all

driven by water power, and were therefore situated somewhere by the banks

of the Water of Leith; but their exact location, except in the case of one

or two which were owned by the Laird of Restalrig, is unknown today.

Bonnington Mills, which we find a possession of Holyrood from their

earliest record, perhaps supplied the needs of the abbot’s lands of

North Leith as well as those of more outlying parts. The mills of the

Laird of Restalrig, specifically known as Leith Mills, were sold to the

city of Edinburgh in 1722 by Lord Balmerino.

The mills gifted to

Edinburgh along with the harbour, though frequently spoken of in later

years as "Leith Mills," are not so designated in Robert the

Bruce’s charter. Leith Mills belonged, as we have already seen, to the

lairds of Restalrig. Where Edinburgh’s mills were situated is not known.

With the harbour they were the earliest of the city’s possessions in

Leith. This royal grant did not confer any right to the use of the banks

of the river, and disputes arose with Sir Robert Logan, the proprietor

which were only settled by the Edinburgh authorities paying him a large

sum of money for the banks, with liberty to erect wharves and quays

thereon, and to make roads through the lands of Restalrig for the

transport of goods and merchandise to and from the city. Their main

highway became the Easter Road of later days, while the abbot and canons

of Holyrood had their own approach to Leith by way of Broughton Loan and

the Bonnington or Western Road, which passed through their own lands all

the way to the ford and ferry across the water to North Leith.

In 1414 Edinburgh made

another bargain with Sir Robert Logan, and obtained a charter from him by

which he granted to the city all the land along the river bank from the

abbot’s lands of St. Leonards, now the Coalhill, to the mouth of the

river, which was then where the Broad Wynd is now, while the waste land

beyond that point, in some way unknown to us today, belonged to Holyrood

Abbey. Up to this time the only means of access to the harbour which Logan

allowed the Edinburgh burgesses was by the narrow yet quaintly picturesque

Burgess Close, now widened into a street, utterly wanting in the old-world

charm that graced its ancient predecessor.

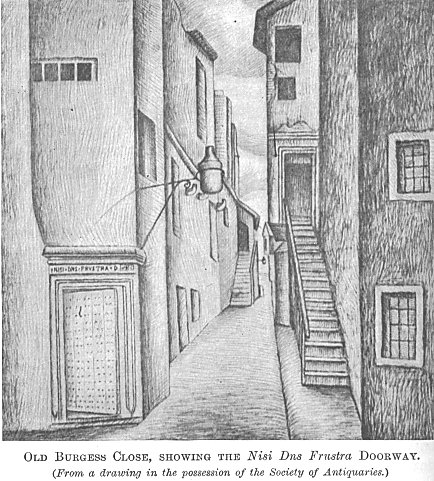

The old Burgess Close, which ran south-east

to the Rotten Row, now Water Street, was not for Leith folks. It contained

the booths and stores of those Edinburgh burgesses engaged in the commerce

of their port. In an old building which formerly stood here, probably at

one time the booth of one of those Edinburgh merchant burgesses, there was

a beautifully moulded doorway with a finely carved lintel containing the

heraldic motto of the city, Nisi Dominus Frustra, in the

abbreviated form Nisi Dns Frustra, and the date, 1573, with what

looked like a merchant’s mark, but which might have been merely

decoration. This is the oldest carved lintel of Leith of which there is

any record, and, curiously enough, the oldest carved dated lintel in

Edinburgh has a variation of the same heraldic motto. The Edinburgh

burgesses compelled the Laird of Restalrig to give them a wider and more

convenient access to their harbour, and in this further grant we have the

origin of Tolbooth Wynd as a street.

The next superiority the

city acquired was that of Newhaven, founded by James IV. in 1504 on lands

acquired from the Abbey of Holyrood in exchange for part of his own domain

of Linlithgow. Here he erected shipbuilding yards and a naval dockyard for

the construction and accommodation of the navy he was so ambitious to

possess. The city of Edinburgh, we are told, did not look with favour on

this new rival to their own port of Leith. James’s naval schemes had

already exhausted his treasury, and, as the sale of Newhaven was in no way

to interfere with the work of his shipyards there, he readily parted with

it in 1510 to the Edinburgh Council, who were only too eager to possess

it, for frequent injury was done to the trading privileges of the royal

burghs by ports outside their control.

|