|

IN the last chapter

we saw how Edinburgh purchased the Shore of Leith from Sir Robert Logan of

Restairig in 1398 and 1414, and the harbour of Newhaven from James IV. in

1510. These purchases were to prove but the first instalments of Edinburgh’s

ultimate possession of all save one portion of the town and lands of

Leith. The next portion of the superiority to be acquired by the city was

Sir Robert Logan’s town of South Leith, which he governed by a baron-bailie,

who was always his kinsman, the Laird of Coatfield. This acquisition of

South Leith did not, of course, include the Abbot of Holyrood’s portion

of the town, the lands of St. Leonards, which extended from the Vaults to

the Brigend. The story of how the Laird of Restairig’s town came into

the possession of Edinburgh is rather complicated, as it is mixed, up with

important State events connected with the troubles of the Reformation and

the misfortunes of Mary Queen of Scots.

In 1556 Mary of Guise, the

Queen-Regent, met a deputation of four Leithers, who wished to negotiate

with her for the erection of the town into a royal burgh, and so raise it

to the same status as Edinburgh. This was really more than Mary of Guise

could possibly accomplish, for such a

Step was certain to be resisted by the city. Edinburgh’s Opposition

would be sure to be backed up by all the other royal burghs, who were

keenly jealous of the extension of their privileges to other towns. The

first step to be taken by the Queen-Regent in support of the ambitions

of the Leithers was to buy up Logan, which she did

for £3,000 Scots, The people of Leith paid over this money to the queen, but all they received in

return were her

letter patent, empowering them to choose bailies and other

officers, and to erect their craftsmen into corporations, which in some cases,

as in those of the tailors and the shoemakers, had already been done by the

Logans.

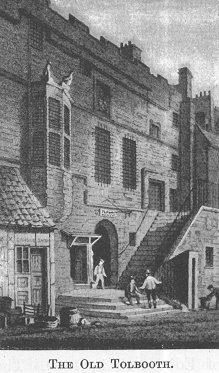

In 1561 Queen Mary —arrived

in Leith from France, and took the government of Scotland into her own hands. Encouraged

and aided by their young queen, whom they expected to raise their town to

the status of a free burgh, the people of Leith in 1564 built a new

tolbooth in the Tolbooth Wynd. The old tolbooth of the Logans, in which

they had held their baronial courts, had been burnt down by Hertford and

never rebuilt. The tolbooth erected in Queen Mary’s time was demolished

in 1819, and a new one—built on the same site, 53—61 Tolhooth Wynd, in

1822—is now occupied as shops and dwelling-houses. In 1565, in a time of

financial need, Queen Mary was granted a loan of 10,000 merks by the city

of Edinburgh on the condition that, if the money was not repaid, the

superiority of South Leith, which her mother, Mary of Guise, had bought

from the Logans with the Leith people’s money, should be given in

exchange for the debt. In 1561 Queen Mary —arrived

in Leith from France, and took the government of Scotland into her own hands. Encouraged

and aided by their young queen, whom they expected to raise their town to

the status of a free burgh, the people of Leith in 1564 built a new

tolbooth in the Tolbooth Wynd. The old tolbooth of the Logans, in which

they had held their baronial courts, had been burnt down by Hertford and

never rebuilt. The tolbooth erected in Queen Mary’s time was demolished

in 1819, and a new one—built on the same site, 53—61 Tolhooth Wynd, in

1822—is now occupied as shops and dwelling-houses. In 1565, in a time of

financial need, Queen Mary was granted a loan of 10,000 merks by the city

of Edinburgh on the condition that, if the money was not repaid, the

superiority of South Leith, which her mother, Mary of Guise, had bought

from the Logans with the Leith people’s money, should be given in

exchange for the debt.

In little more than two

years thereafter followed all the tragic events that landed Queen Mary in

an English prison, and her loan of 10,000 merks was never repaid. This, we

know, was just what the Edinburgh Town Council wished, although they

themselves had the utmost difficulty in repaying the merks to the city

guilds from whom they had borrowed them. The merk was not a coin, but a

money of account, as the guinea now is today, and was equal to 13s. 4d.

Logan’s town of South Leith, as well as the harbour, was now completely

under the Town Council of Edinburgh, and later, in 1636, became a burgh of

barony under the superiority or overlordship of the city.

The lands of North Leith,

including those of St. Leonards on the south side of the water extending

from the Brigend to the Black Vaults, fell into the hands of Edinburgh in

1639. They had formed Part of the princely possessions of the Abbey of

Holyrood. On the confiscation of the Church lands at the Reformation North

Leith had become lay property, and, with most of the lands of Broughton,

eventually passed into the hands of the first Earl of Roxburgh, who also

owned the Canongate. These two properties, the Canongate and North Leith,

the earl sold to the governors of George Heriot’s Hospital, and from

their ownership they passed into the possession of the city.

The Canongate and North Leith were made one barony—the

barony of the Canongate—which was ruled by magistrates appointed by

Edinburgh. These bailles of the Canongate had no connection with those of

South Leith, although they were all appointed by the Town Council of the

city. For the next two hundred years, therefore, South Leith and North

Leith were entirely separate and independent of each other.

After the disastrous Battle of Dunbar in 1650 Leith

was occupied by some regiments of Cromwell’s troops under Major-General

Lambert. Some English families then came to settle in the town, but they

found their industrial activities so hampered by the restrictions of

Edinburgh that, along with the people of Leith, they petitioned General

Monk, Cromwell’s commander in Scotland, to have Leith declared a

separate burgh from Edinburgh. But nothing came of it. Monk thought the

town was under the greatest slavery that ever he knew, and said so; but on

Edinburgh paying £5,000 sterling towards the cost of his great fort,

whose memory we still preserve in the name of the Citadel, all her trade

privileges were confirmed.

In the wild outburst of loyalty at the Restoration

Cromwell’s Citadel was dismantled, to the great joy of the people.

Charles II. gifted it, with its haven and port, to the Duke of Lauderdale,

the king’s powerful minister in Scotland. He erected it into a burgh of

barony and named it Charlestown in honour of the king. Here was a burgh

and its port placed between Edinburgh’s ports of Leith and Newhaven, and

there was no saying how much harm it might do their trade in such

unscrupulous hands as those of Lauderdale. The Citadel had already cost

Edinburgh £5,000 under the dread of losing her trade privileges. Now once

more she had to dip deep into her

coffers, for it cost her £6,000 more before Lauderdale could be induced

to hand it over to her possession.

Besides the district of St.

Leonards on the south side of the water, the Abbey of Holyrood also owned

the land at the mouth of the river which now extends from the Broad Wynd

to Bernard Street. How it came about that the lands of the Abbey and those

of the Laird of Restalrig were thus intermingled we cannot now tell. This

portion of the Abbey’s possessions had been purchased by the Crown, and

on it had been erected the King’s Wark, a kind of palace and royal

arsenal combined, which was the most prominent object on the Shore of

Leith, and, like the Signal Tower of later centuries, formed a striking

and imposing termination to its line of buildings. Immediately beyond the

King’s Wark were the Lang or East Sands, now the line of Bernard Street,

over which, in stormy weather, the sea swept in long rolling waves, to

dash themselves into foam against its northern wall.

Leith was then, and had

been from a very early period in its history, the port at which victuals

and other commodities destined for the king’s use were landed. It was

therefore necessary to have Government buildings where such goods could be

stored till they were actually required for use. From a very early date

houses had been rented in Leith by the king for this purpose. When the

English held the port in the days of Edward I. they commandeered the house

of John de Lestalric for their stores. De Lestalric was at this time

fighting Scotland’s battle by the side of Robert the Bruce. This house

of De Lestalric’s was a great storehouse like the Black Vaults rather

than a dwelling. It was used by the English as a kind of distributing

depot for army stores brought by sea from Berwick. To James I. we owe the

erection of a special building for housing the royal stores. From its

great size and many uses as Government arsenal, naval yard, and even royal

palace, this building was named the King’s Wark. In the King’s Wark

and in the royal arsenals at Edinburgh Castle and Holyrood cannon were

first cast in Scotland.

The Wark would seem to have

been the principal arsenal of the country all through the reigns of the

Stuart kings. It appears to have been largely extended in the reign of

James II. Its various buildings covered a large area of ground, and from

its situation at the mouth of the harbour, and its great tower, it would

seem also, like the Martello Tower in 1809, to have been designed as a

kind of citadel to ward off the attacks of any enemy approaching from the

sea. It was much damaged, though by no means destroyed, when Leith went up

in flames during Hertford’s destructive invasions. It was repaired and

largely rebuilt after Queen Mary’s return from France in 1561, and on

James VI. succeeding Elizabeth on the throne of England in 1603 he gifted

the whole building to Bernard Lindsay, one of his Court favourites. In

1647 Lindsay’s sons sold the King’s Wark to the Town Council of

Edinburgh, to whom its lands still belong.

There remained only one

part of Leith over which Edinburgh never had any jurisdiction, because it

at no time was any part of her property. This was the district of St.

Anthony’s, which James VI. erected into a barony and gifted to the Kirk

Session of South Leith. This barony included the Lees quarter of the

Yardheads which had at one time been the orchards of the canons of St.

Anthony. The portion next King Street and Cables Wynd, which the Logans

had kept in their own hands, was purchased with what remained of their

barony of Restalrig by Lord Balmerino, who added it to his separate barony

of Wester Restairig or the Craigend, but better known latterly as the

Calton, a village on the slope of the Calton Hill overlooking Leith

Street, and part of which still survives under the name of High Calton.

The dwellers in the Calton were shut off from the city of Edinburgh and

from their nearest neighbours in the Canongate by the steep slopes of the

Calton Hill, for there was no Waterloo Place with its great Regent Arch in

older days. The villagers of the Calton belonged to the parish of South

Leith, in whose church their gallery was indicated by a carved panel

inscribed with the legend,

"16. FOR THE CRAIGEND.

56."

The site of this gallery on

the north side of the nave is marked by a facsimile of this panel, but the

original one, erected in the days of Cromwell’s stern rule, is now in

the Antiquarian Museum in Queen Street, where it was sent when the Church

was stripped of so many of its older features during the restoration of

1847. These old villagers buried their dead in the churchyard in the

Kirkgate. The distance of the Calton from South Leith, however, induced

its inhabitants in 1718 to set up what is known today as the Old Calton

Burying Ground. This old cemetery was cut in two on the formation of

Waterloo Place in 1815. The smaller part enters by the original iron gate

from the centre of the village while the larger part, containing the old

collecting box for the poor, enters by a separate gateway from Waterloo

Place. The Town Council of Edinburgh purchased the lands of Calton from

Lord Balmerino in 1724, and in this purchase was included that portion of

the Yardheads which had belonged to the former lords of the barony of

Restalrig, the Logans.

The story of how Edinburgh

acquired the superiority of Leith, in order the more effectually to

enforce and maintain her trade privileges as a royal burgh, has now been

told. The burgesses of that much favoured burgh, through their trade

monopoly, had obtained possession of the harbour in the days of Alexander

III., if not even much earlier. To this they added part of the Shore in

1414, Newhaven in 1510, Logan’s town of South Leith in 1567, North Leith

in 1639, the Citadel in 1663, and the Calton barony in 1724. The only part

of the town to remain in the hands of the Leithers was the barony of St.

Anthony.

Each of these different

districts had its own baron baffle, and thus, although they were all

immediately adjacent and in some cases even intermingled, they were each

under separate jurisdiction. However much such a state of matters may have

suited those earlier centuries when overlords were the arbitrary masters

of their own lands and their inhabitants, it was altogether unsuited to

modem times and the needs of a growing town and increasing population. The

conviction of the common interests and needs of these separate but

contiguous areas became so strong that in 1833 their antiquated system of

government was swept away, and Leith became a separate parliamentary

burgh.

|