On Tuesday morning, the

19th of August, a gloomy misty day that seemed to be grieving in sympathy

with her on her separation from her beloved France, Queen Mary arrived in

Leith Roads. She had not been expected till the last days of the month,

when the nobles and gentry had been summoned "with their honourable

companies to welcome her Majesty." No. preparation had therefore been

made to receive her, but the cannon of her two galleys soon brought out

the people in crowds to greet her. She was accompanied by her three uncles

of the House of Guise, by her four Maries, who, like herself, owing to

their long residence in France, always spoke Scots with a French accent,

and others of lower order. On landing in the forenoon beside the King’s

Wark, a part of the Shore that has seen so much of the pageantry of

Scottish history, she was received by the Earl of Moray and a great crowd

of all ranks.

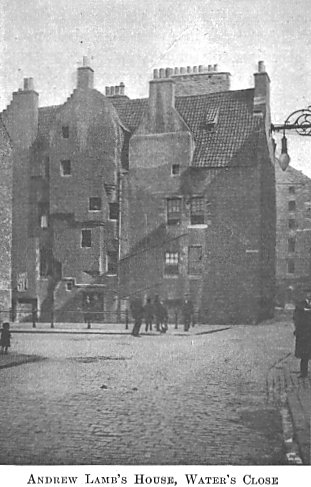

As no preparation bad yet

been made for her at Holyrood she "dynit in Andro Lambis house,"

in Leith, where, according to John Knox, she remained till towards

evening, when she proceeded to the Palace. Queen Mary had not far to

travel after landing to reach Andrew Lamb’s house, for it stood, as

parts of it may still, at the head of the close which has been named from

himself as its chief resident—Andrew Lamb’s Close— and is so

familiar to-day to lovers of old-time Leith by the name of an eighteenth

century inhabitant, Willie Waters, of whom no tradition or history has

been preserved.

At the head of Water’s

Close, on the line of Water Street, stands a fine specimen of the

picturesque street architecture of days long gone by, which shows us that,

if the streets of the Leith of other and older days were narrow and

gloomy, the eye of the wayfarer was ever being arrested by the quaint and

pleasing variety presented by the outline of turret, roof, and gable

against the background of the sky. This Water’s Close mansion, the

finest specimen of old Scottish architecture in Leith, was the house of

the Lambs and theft descendants down to a century ago; but how much of the

old house as it stands to-day dates from Queen Mary’s time it is hard to

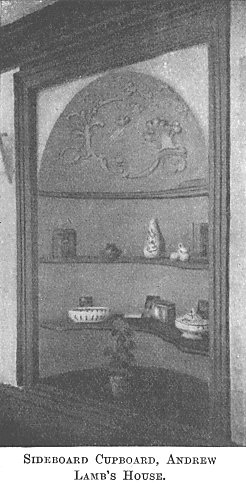

say. The dining-room of the Lambs, with its early seventeenth-century

alcoved sideboard, now forms a house by itself of three apartments, and

the other rooms have been similarly transformed. A great courtyard, which

was once the garden of the mansion and in which Queen Mary may have

strolled on that gloomy far-off August day, is now a tradesman’s yard,

and may be entered from a pend in Water Street.

At the head of Water’s

Close, on the line of Water Street, stands a fine specimen of the

picturesque street architecture of days long gone by, which shows us that,

if the streets of the Leith of other and older days were narrow and

gloomy, the eye of the wayfarer was ever being arrested by the quaint and

pleasing variety presented by the outline of turret, roof, and gable

against the background of the sky. This Water’s Close mansion, the

finest specimen of old Scottish architecture in Leith, was the house of

the Lambs and theft descendants down to a century ago; but how much of the

old house as it stands to-day dates from Queen Mary’s time it is hard to

say. The dining-room of the Lambs, with its early seventeenth-century

alcoved sideboard, now forms a house by itself of three apartments, and

the other rooms have been similarly transformed. A great courtyard, which

was once the garden of the mansion and in which Queen Mary may have

strolled on that gloomy far-off August day, is now a tradesman’s yard,

and may be entered from a pend in Water Street.

Later in the day the

youthful queen continued her journey to Holyrood. Though

she captivated all by her beauty and stately carriage, her cavalcade did

not form the brilliant pageant associated with the arrival of former

princesses at the Shore, for the two Dutch ships carrying her horses and

baggage had been captured by English war

vessels and detained at Newcastle. In Mary’s eye the ill-favoured

little Scottish hackneys, so meanly caparisoned, on which she and her

escort rode from the Shore to Holyrood, looked wretched indeed compared,

with the superb palfreys and their gay trappings to which she had been

accustomed in France.

Story, but not history,

associates two other Leith mansions with the ill-fated Queen Mary. The one

is Hillhousefield House, now renamed Tay House since engineering works

have invaded its once pleasant lawns and gardens that used to stretch down

to the river’s edge; and the other is the stately old mansion of Trinity

Grove, which did not come into existence till long after Queen Mary’s

time. According to story, the weeping thorn that once adorned the old

garden of Hillhousefield was planted by the hapless queen’s own fair

hand.

But like many another

fondly believed Queen Mary tree, it was not in reality planted by the

queen, but grown from a slip taken from a tree the queen was believed to

have planted. The name naturally continued to attach itself to the tree,

but in the lapse of years the reason for the name passed from memory. The

story of the ancient gardener of Trinity Grove, on his way to Holyrood

with his basket of nettle tops over his arm for "sallets" to the

queen, of which her French upbringing had made her extremely fond, is a

pretty but wholly fanciful tale.

If the sorry steeds which

conveyed Queen Mary and her retinue to Holyrood gave her an unfavoarable

impression of her native land, that feeling would in no way be relieved by

the appearance of Leith at this time. The burnings of Hertford, and the

destructive fire of the English guns during the siege of the year before,

had left much of the town in ruins, of which the greater

Kirkcaldy

made a raid on Leith. Gathering all the victuals he could seize from the

merchants and their ships, he now stood prepared for a long siege. With

the guns of the Castle pointed downward on the houses, he was easily

master of the whole city, from which he drove the new Regent Lennox, the

Earls of Morton, Mar, and Argyll, and some two hundred of the leading

burgesses on the king’s side. Among these were Edward Hope and Adam

Fullarton, two strenuous supporters of Knox and the Reformation, and for

that reason strongly opposed to the cause of Queen Mary. The king’s men

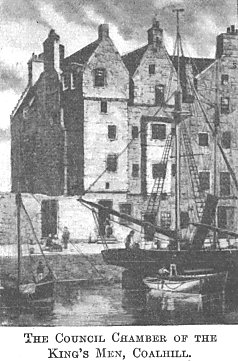

took up their quarters in Leith. It is at this time that the old

Renaissance building facing the Coalhill comes into history as their

council chambers, where they discussed their plans for carrying on the

war. For this reason the old alley leading to it from behind became known

as Parliament Square, which has now given place to Parliament Street.

During the two years the king’s men were in Leith there could be no

regular government of Edinburgh by the provost and magistrates, and so we

have a gap in the council records, which do not again begin until some

months after their return to the city.

Kirkcaldy

made a raid on Leith. Gathering all the victuals he could seize from the

merchants and their ships, he now stood prepared for a long siege. With

the guns of the Castle pointed downward on the houses, he was easily

master of the whole city, from which he drove the new Regent Lennox, the

Earls of Morton, Mar, and Argyll, and some two hundred of the leading

burgesses on the king’s side. Among these were Edward Hope and Adam

Fullarton, two strenuous supporters of Knox and the Reformation, and for

that reason strongly opposed to the cause of Queen Mary. The king’s men

took up their quarters in Leith. It is at this time that the old

Renaissance building facing the Coalhill comes into history as their

council chambers, where they discussed their plans for carrying on the

war. For this reason the old alley leading to it from behind became known

as Parliament Square, which has now given place to Parliament Street.

During the two years the king’s men were in Leith there could be no

regular government of Edinburgh by the provost and magistrates, and so we

have a gap in the council records, which do not again begin until some

months after their return to the city.

The Leithers again suffered

something of the horrors of war, for skirmishes took place daily between

the king’s men in Leith and the queen’s men from the city and the

Castle. But they suffered still more from the harsh treatment and

high-handed dealings of the king’s men from Edinburgh, who had forcibly

taken up their quarters in their midst. These did not forget that the

Leithers had been specially favoured by the dethroned queen, for she had

endeavoured to make their town a free burgh to the detriment of the city

which now ruled them. Their sympathies were thus strongly on the side of

the ill-fated queen and the youthful yet unruly Laird of Restalrig, who

was fighting under the banner of the gallant Kirkcaldy in Edinburgh

Castle.

For these causes little

consideration was shown to the Leithers. The Edinburgh burgesses who had

fled from Kirkcaldy’s guns began to erect houses and booths on their

lands without ever saying by your leave, and when Helen Moubray, a

great-granddaughter of Sir Robert Barton, complained to the regent, no

satisfaction was given. The rude soldiery of Morton who bore the brunt in

the fighting had to be lodged and victualled by the oppressed inhabitants,

who in many cases were forbidden the use of their own houses, which

had been taken possession of by the rough soldiers of the harsh and cruel

Morton.

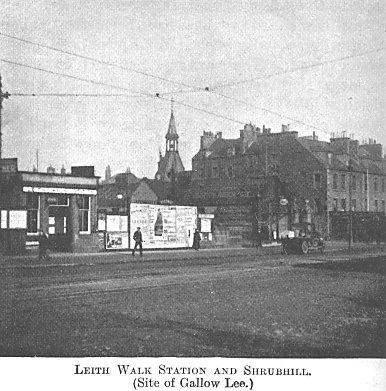

After the death of Lennox

and Mar, James, Earl of Morton, became regent in name as he had all along

been in fact. Morton was a man of cruel and callous nature, and continued

the fight against Kirkcaldy and the queen’s men with the utmost

bitterness and cruelty. "No quarter," was the cry of the king’s

men now that Morton was in command. All prisoners who chanced to fall into

his hands were hanged in full view of the Castle garrison at the Gallow

Lee, where Leith Walk Station and the tramway depot are now. The queen’s

men of course retaliated in like manner, for no war stirs up so much hate

among a people as civil strife, and Kirkcaldy would string up an equal

number of prisoners on the Castle Hill or Moutree’s Hill, now covered by

the Register House. And so the cruel strife went on.

Slaughter and outrage were

everyday events. Trade was brought to a standstill and hard times were

everywhere, for the fields between the two towns being a daily

battle-ground were left untilled. The farmer’s horse was commandeered

for Morton’s troopers or yoked to his lumbering artillery. Kirkcaldy

defended the Castle with the utmost courage and skill, and was so

confident in his ability to hold out for any length of time against Morton

alone that he indulged in a "rowstie ryme "—that is, a rude

ballad—in which he mocked the attempts of his enemies to drive him from

his stronghold—

"When they have lost as

mony teeth

As they did at the siege of Leith,

They will be fain to leave it."

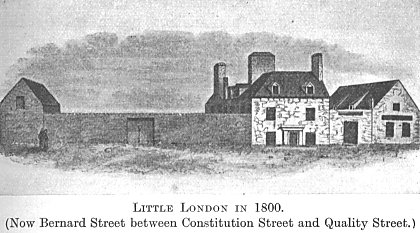

But Kirkcaldy in his plans

of defence had taken no account of the fact that, just as at the siege of

Leith in 1560, Morton might be aided by a force from England; and this was

what happened, for Queen Elizabeth, anxious for the success of the

Protestant cause, sent a siege train to Leith by sea and an army under Sir

William Drury from Berwick. They encamped by the Links in the

neighbourhood of Bernard Street, perhaps at a spot which appears in local

records six months later as Little London, seemingly for no other reason

than this association with Drury’s men. What Morton failed to do,

treachery within the Castle and the English guns without accomplished in

May 1573, when Kirkcaldy and Lethington surrendered to Sir William Drury

on condition that their lives would be spared. They were afterwards

brought to the English camp at Leith. Lethington died in the Leith

tolbooth, but whether from disease or by his own hand or those of his

enemies has never been quite determined. Kirkcaldy, by Elizabeth’s

orders, and to the shame and grief of Drury who afterwards resigned his

command, was surrendered to the tender mercies of the ruthless Morton and

the burgesses of Edinburgh who had suffered so much at his hands. He was

condemned to the ignominious death of hanging.

In his day of trouble

Kirkcaldy’s thoughts turned to his old friend David Lindsay, the

much-esteemed minister of South Leith. When Knox was dying he had sent

David Lindsay to warn Kirkcaldy, for the love he bore him, that he was

fighting, not only in a losing cause, but in one that would bring shame

and disaster to himself. That prophecy was now about to be fulfilled, for

Kirkcaldy was hanged at the Cross two months after his surrender of the

Castle, the faithful David Lindsay standing by him to the end. By such

shameful death died the gallant Kirkcaldy of Grange, the greatest Scots

soldier of his day, and the last hope in Scotland of the cause of Queen

Mary, who wept bitterly in her English prison when the Earl of Shrewsbury,

with unkindly intent, told her the ill news of his death. The Laird of

Restalrig, though condemned to die also, was afterwards set free, but on

the same scaffold with Kirkcaldy was hanged another of the Castilians, as

they were called, James Mossman, Queen Mary’s goldsmith, whose initials

and coat-of-arms, with other interesting carved stonework, still adorn his

ancient booth in the High Street—now John Knox’s House. Mossman’s

descendants of the same name are still goldsmiths in Edinburgh, as one may

see from the name over the doorway of the jeweller’s shop at 134 Princes

Street.

The regent Morton and the

king’s men, driven to Leith by the Castle guns, now returned to their

ruined houses in the city. These they repaired or rebuilt, and in Fountain

Close, immediately opposite John Knox’s House, are to be seen the two

carved lintels with the inscription VINCIT VERITAS—that is, The truth

conquers—and other pious legends which Adam Fullarton placed over

his doorways in 1573 in celebration of his party’s triumph. And now

Leith was to be free from the cruel experience of war in her midst for the

next seventy years, but companies of armed men embarking at the Shore of

Leith for service abroad was to be a familiar sight for many years to

come.

The ordinary rank and file

of the Castilians were set free, says a contemporary chronicler, on

condition that they enlisted for service in the Netherlands, where the

Duke of Alva and the other merciless lieutenants of the bigoted Philip II.

of Spain were oppressing Catholics and Protestants alike, but especially

the latter. The fall of Edinburgh Castle and the end of the Civil War had

deprived many soldiers, both king’s men and queen’s men, of

employment. Owing to the dearth of food the Government ordered that all

idle men and soldiers were to quit the city and might pass to the wars in

Flanders, where they were soon to be found fighting side by side with the

Netherlanders against their Spanish oppressors. Few ever saw their native

land again, for the ferocious Spaniards gave no quarter to those who fell

into their hands, but their memory can never die so long as Scots maidens

sing the fine old ballad with its beautifully pathetic refrain, "The

Lowlands of Holland hae twined my love and me."

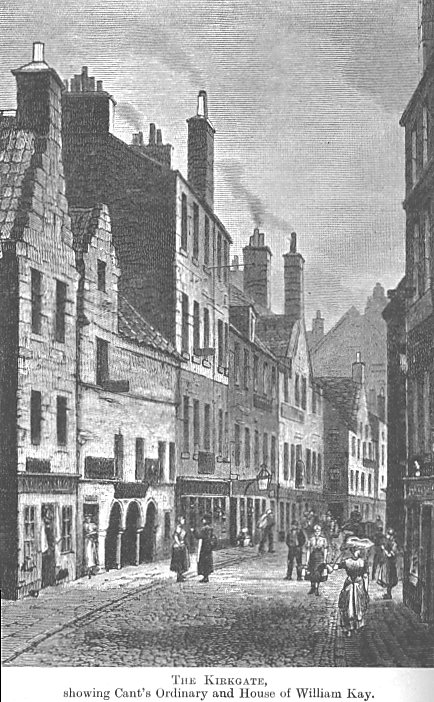

There is one other incident

associating the name of the much-hated regent Morton with Leith. His

policy as regent was much opposed by many of the leading nobles, but in

1578 a reconciliation was effected, when Morton and his chief opponents,

including the Earls of Argyll, Montrose, Arran, and Boyd, celebrated the

event by dining jovially at a hostelry in Leith kept by one William Cant.

There had been Cants in Leith, mostly sailormen, for many generations.

Cant’s Ordinary or Hostelry is supposed to have been the quaint old

building raised on pillared arches which for centuries stood in the

Kirkgate at the head, of Combe’s Close. The site of this ancient place

of entertainment is now fittingly occupied by Kinnaird’s Restaurant. The

ceiling of Mr. Kinnaird’s shop is a facsimile of the decorated plaster

ceiling of the so-called Queen Mary room of its ancient predecessor, whose

outline in carved stonework may be seen on an ornamental panel in front of

the new building.

The house with its gable to

the street immediately to the left of the supposed Cant’s Ordinary, and

demolished at the same time as that ancient hostelry, was for centuries

the property of a family named Kay. Here, or in its predecessor on the

same site, in the reign of James VI., dwelt William Kay, mariner.

A noted interest attaches

to this old Leith sailorman, for his descendants are actively engaged in

the commercial life of the Port to-day. In every generation of this

family, from William Kay’s time until now, one or more members always

seem to have followed a sea-faring life. Robert Kay was a shipmaster in

1739. William Kay was chief mate of the sloop Culloden in 1787,

when he was exempted from capture by the Press Gang, which, during the

American and Napoleonic wars, periodically raided the Port from the

warships in the Roads. It was from Leith aboard one of the warships in the

Forth, although he was not a Leith man, that "Admiral" Parker,

the leader of the mutiny at the Nore in 1797, enlisted in the navy.

Another member of the Kay family was captain of the Happy Janet which

brought Mons Meg from the Tower of London to Leith in 1829, when the whole

town poured out to welcome the great "bombard" just as it had

done some four hundred years before when she was unshipped on the Shore

from Flanders. A great-grandson of the commander of the Happy Janet is

an officer aboard a Leith steamer to-day.

When the fleet of James 1V.

sailed to France in 1513 one of the ‘ blue jackets" aboard the Great

Michael was a shipwright named John Kay. If this sailorman was of the

same stock as William Kay, near neighbour to the host of Cant’s Ordinary

in 160], then we have in Leith to-day members of a family that has the

proud, and surely unique, distinction of having been associated with the

shipping of the Port from the heroic age of the Bartons and Sir Andrew

Wood to our own day, a period of more than four hundred years.

The execution of Queen Mary

in 1587 caused much indignation in Scotland, especially among a section of

the nobles. When the Court went into mourning the young Earl of Bothwell

appeared in a coat of mail, which he declared was the best "dule

weed" for the dead queen. There were other causes of hostility at

this time which mischief-makers made the most of to stir up strife between

the two peoples. The English ambassador, when he once more dared show

himself in Edinburgh after Queen Mary’s execution, reported to Queen

Elizabeth that the acts of piracy on the part of English seamen against

Scottish ships were more numerous than in time of open war, and were so

much resented that they were made use of to inflame the minds of the

people against England. An English pirate cruised off the May Island and

despoiled many ships entering the Firth. She was reported to belong to Sir

Humphrey Gilbert, but that could not possibly have been true, for the

gallant Elizabethan sailor had set out on what was to prove his last

voyage just a month before, taking with him all the ships he could muster.

Behind the May had always been a favourite lurking-place for English

pirates.

In 1587 Edinburgh

commissioned and equipped one of Leith’s largest ships to "pass

upon the Inglis pyrats" haunting this quarter, but with what success

does not appear. "But it so happened in God’s pleasure," so we

are told after the pious manner of the time, that the English pirates did

not always have it their own way, for George Pantoun, a local skipper, and

his good ship making their way homeward from Danzig to Leith brought a

whole ship’s crew of these rievers with him, most of whom were hanged on

the Sands, which had for long been the customary

place of execution for those who chose to sail under the "Jolly

Roger." Many a bold pirate closed his lawless career on the gibbet on

Leith Sands, where his body continued to hang in chains as a warning, but

seldom, it would seem, as a deterrent, to others. The first notice we have

of the bodies of criminals being suspended in chains in Scotland is in

1551, when John Davidson was first hanged and then hung in chains on the

Sands of Leith "for the violent piracy of a French ship of

Bordeaux."

But now the Scots and

English were to lay aside their mutual hostility for a time in face of a

common danger. This was the invasion of the Spanish Armada, perhaps the

best-known fact in British history. Even the pirates were received into

favour when they came to guard against the approach of the Spanish

galleons; for had England gone down before the might of Spain, the

subjugation of Scotland must have followed immediately thereafter. The

merchants of Edinburgh and the sailormen of Leith had much cause to fear

and hate the Spaniard. Their chief trade was with the Netherlands, and it

had suffered greatly through the confused and unsettled state of those

provinces, owing to the cruel oppression of their Spanish rulers.

Some of the more lawless

Scots nobles like the Earl of Huntly, the slayer of the "Bonnie Earl

of Moray," and perhaps the plotting Logan of Restalrig, were quite

ready to join Philip in an invasion of England, or even to turn against

their own country to avenge Queen Mary’s death. Spies in the interests

of Spain frequently came and went through the Port of Leith between Philip

and these Scots sympathizers. One of these spies, Colonel William Semple,

a member of an old Scots family who had fought on the side of Spain

against Holland, took up his lodging in Leith in the summer of 1588,

nominally as an envoy from the Prince of Parma to King James, but really

to negotiate with Huntly in the interests of Spain.

On August 8th, the very day

on which the Great Armada was being driven in disastrous rout before the

English "sea-dogs," a Spanish warship with some two hundred men

aboard anchored off the Port and sent a boat ashore with sixteen men,

bearing dispatches from Parma to Colonel Semple. But Sir John Carmichael,

the Captain of the King’s Guard, was too clever for them. He not only

arrested the crew of the Spanish boat, but at the same time captured

Semple and all Parma’s dispatches. King James, with beating of drums and

the ringing of the alarm bell in the Tolbooth, commanded the men of Leith

to hold themselves in readiness to oppose any further attempts of the

Spaniards to send men ashore.

Huntly advised Parma to

invade England through Leith, which he could then hold as a postern giving

easy entrance into England; but the ships of the "Beggars of the

Sea" kept Parma shut up in the Netherlands. The danger to Scotland

from Spain was therefore very real and very great. The result was a treaty

for mutual defence between King James and Queen Elizabeth, and Scotland’s

fighting men were ordered to hold themselves in readiness to muster on

Leith Links to repel the invader should he succeed in landing. Watchers

were posted round the coast, and the balefires were to be lit on the first

alarm.

Terrible was the

consternation and fear in Leith and Edinburgh when it was known that

"that monstrous navie was about our costes." As in the Great

War, lying rumour brought in many false alarms. Now the Spaniards, like

the Germans, had landed at Dunbar, now at St. Andrews, and now somewhere

in the north. It was not until a month after the Armada had left Spain

that it was known to be in full flight round our shores, little better

than so many storm-shattered hulks, four of which came to grief on the

coast of Mull. The shipwrecked crews of these vessels, some seven hundred

all told, "for the maist pairt young berdless men, trauchled and

hungered," and utterly wretched, were all that the people of Leith

saw of the Spanish Armada, for from the Shore, after being kindly treated,

they were shipped over to the Duke of Parma in Flanders.

The fear and alarm with

which the Leithers awaited the approach of the Armada were now changed to

thankful prayers and joyful songs. In common with the people throughout

England and the greater part of Scotland, the Leithers gathered in their

two parish churches and poured forth their gratitude to God for His

goodness and mercy. This was done in both countries in the words of the

76th Psalm, which celebrates Israel’s miraculous deliverance from King

Sennacherib and his Assyrian host.

A Scottish poet,

calling upon his countrymen to celebrate with rejoicing so signal a

deliverance, said,—

"Expose your gold and shyning

silver bright

On covered cupboards set in open

sight."

Such

a cupboard or open sideboard with stuccoed decoration still survives in

what was once the dining-room of Andrew Lamb’s house in Water’s Close,

where Mary spent the first day on her unexpected arrival from France.

Such

a cupboard or open sideboard with stuccoed decoration still survives in

what was once the dining-room of Andrew Lamb’s house in Water’s Close,

where Mary spent the first day on her unexpected arrival from France.

Of all the carved stones of Leith, that

which above all others engages our interest and excites our curiosity is

the upper of the two panels built into the wall of the house immediately

opposite the head of St. Andrew’s Square in the Main Street of Newhaven.

The sculptures on the lower panel are similar to those on the south wing

of the Trinity House in the Kirk-gate. They are the heraldic arms of the

Mariners’ Incorporation of the Trinity House, and at one time must have

adorned some of their property in the neighbourhood of Newhaven. How old

this stone may be there is no date to show, but that the arms themselves

must have been adopted over two hundred and fifty years ago the carvings

on the stones themselves indicate, for, instead of the sextant, the shield

bears its predecessor, the cross-staff, which has been obsolete since the

time of William of Orange.

It is the upper and more

ancient of the two panels, however, which specially arrests our attention,

for it bears, carved in curious fashion, the ever-memorable date 1588, the

year of the destruction of the Great Armada.

Beneath this date is

sculptured a sixteenth-century ship with the flag of St. Andrew. Scotland’s

naval ensign before the Union of 1707, flying from each masthead. Beneath

all, in capital letters, is the legend, "In the Neam of God."

The ship sculptured here much resembles the model now in the Royal

Scottish Museum of the Yellow Carve!, that gallant old ship of Sir

Andrew Wood.

Is

it only a remarkable coincidence that this stone should bear so

significant a date, or is there some connection between it and the rout

and ruin of the vaunted Invincible Armada? Does it not seem as if the

people of Newhaven wished to have some permanent memorial to remind them

and those who came after them of God’s signal mercy and goodness in so

great a time of peril? If any of their number had been refugees from the

hated tyranny and cruel persecution of the Spaniards, we can well

understand the gratitude that led them to erect this memorial for their

second escape from the terrors of the Spanish Fury and the cruelty of the

pitiless Spanish oppressor.

The year following the

destruction of the Spanish Armada saw another royal princess set sail from

her native land to become a Scottish queen. This was Anne of Denmark, who

was married to James VI. in 1589. On setting forth on her voyage her ship

was so tempest-tossed and driven out of her course that she had to seek

shelter in Christiania Harbour, where she remained all through the winter.

James, becoming impatient at her non-arrival, sailed to Norway to bring

her home, and the royal pair were married at Christiania by David Lindsay

of South Leith, who had accompanied King James overseas, because he was

"the minister whom the Court liked best." They set sail from

Norway in the ship of Captain John Dick, whose only son, Sir William Dick

of Braid, afterwards became a wealthy Edinburgh merchant prince and

Covenanter, and Provost of the city.

On their arrival in Leith

in May of the following year the whole town gathered on the Shore and Long

Sands to welcome them, just as they did eleven years later when James

crossed the Forth to Edinburgh after his escape from Gowrie House. A

thanksgiving service for their safe arrival was held in St. Mary’s Kirk.

As Holyrood was not yet ready for their reception, they stayed for six

days at the King’s Wark with the father of Bernard Lindsay, and then

they passed on to Holyrood, the queen and her ladies riding in a coach

drawn by eight great horses of her own, all richly caparisoned. The

members of the trade incorporations, all armed as if for war, lined both

sides of the way to the bounds of the town, when the duty was taken up by

the men of Edinburgh and the Canongate.

James and his loving

subjects had good reason, so he and they at least believed, to be thankful

for his safe arrival from overseas, for it was discovered from a maid

suspected of witchcraft that the storms which had so beset his homeward

voyage had been the malignant work of witches, who wished to drown both

him and his young queen. These witches had met at the Fairy Holes, near

Newhaven, and then, sailing out to Leith Roads in riddles, had raised the

storms by means of a christened cat which was given them by Satan himself.

All these absurdities were most solemnly believed by both king and people,

and a number of so-called witches were first strangled and then their

bodies were burnt to ashes for their supposed share in so wicked a plot.

Such absurd beliefs show us

how superstitious the people of Edinburgh and Leith were in those days;

and, indeed, right down almost to the close of the eighteenth century many

firmly believed in witchcraft. The place of execution for witches in Leith

was the Gallow Lee, once a small hill at Leith Walk Station, of which a

part still survives under the name of Shrub Hill. Here in 1664 nine

witches, who were first mercifully strangled, had their bodies burnt to

ashes; and in 1678 five more met a similar fate. The witch burning in

Leith after James’s voyage from Norway has been made the subject of a

long ballad by Robert Buchanan, entitled The Lights o’ Leith, of

which two verses are quoted below—

"‘The

lights o’ Leith ! the lights o’ Leith !’

The skipper cried aloud—

While the wintry gale with snow and hail

Blew snell thro’ sail and shroud.

"High up on the quay

blaze the balefires, and see!

Three stakes are deep set in the ground,

To each stake smear’d with pitch clings the corpse of a witch,

With the fire flaming redly around !"