|

THE people of Leith and

Edinburgh had long hoped that when Queen Elizabeth died their own King

James would be called to the English throne as her successor. And so it

came to pass. But could they have foreseen the evils the Union of the

Crowns was to bring in its train for them, their joy and pride in seeing

their king ride forth from Holyrood amid the thunder of the Castle guns to

rule over the "auld enemy" would have been sadly sobered and

restrained. Leith had the honour of seeing three of her townsfolk

accompany King James on his journey to London. There was the first Lord

Balmerino, who had succeeded Sir Robert Logan as Laird of Restalrig, and,

as Secretary of State, on Queen Elizabeth’s death had proclaimed James

VI. at the Cross of Edinburgh as King of England. With him were David

Lindsay, Bishop of Ross as well as senior minister of South Leith, a great

favourite at Court, and Andrew Lamb, Bishop of Galloway, in whose father’s

house in Water’s Close Queen Mary had been hospitably entertained when

she arrived so unexpectedly from France.

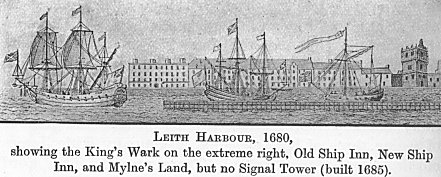

Before setting out for

England James ordered that the King’s Wark and the adjacent lands and

buildings associated with it should become a barony, and this he gifted to

the groom of his chambers, Bernard Lindsay, granting him also a tax of £4

Scots on every tun of wine sold in the taverns in the King’s Wark, of

which there were never to be more than four. From this tax he was to erect

in the King’s Wark a bourse or exchange for merchants "for the

decorating of the pier and Shore of the haven of Leith." This bourse

has long ago disappeared, and so has its successor at the foot of Queen

Street, a locality which old residenters still call the "Burss."

The French name bourse is a relic of the French occupation of Leith

in the time of Mary of Guise and the long trade connection of the town

with France.

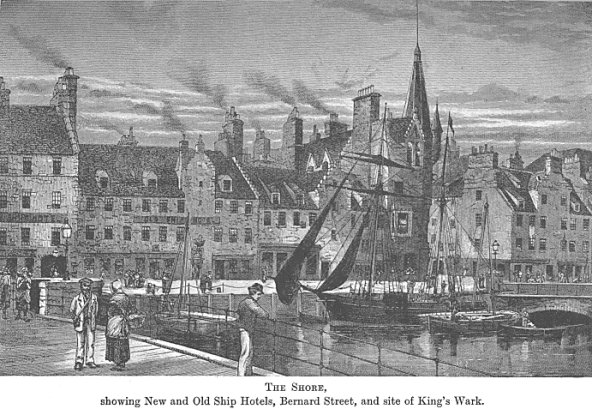

The word is still a

place-name in Leith in a corrupted form in Timber Bush. Leith has to-day a

memorial of Bernard Lindsay in Bernard Street, which was opened right

through a part of the King’s Wark more than one hundred and fifty years

ago.

A considerable yearly

income in the way of rents was derived from the buildings that went to

form the King’s Wark. It was out of these that James III. and James IV.

gifted the annual grant of £28 to the Collegiate Church of Restalrig,

which Bernard Lindsay continued to pay to South Leith Church. When the

Town Council of Edinburgh purchased the King’s Wark in 1647 they became

liable for this financial burden on the property, which they pay annually

to the South Leith Kirk Session, a yearly transaction that links our days

with

"The old unhappy

far-off times

And battles long ago,"

for it was in 1512, the

year before Flodden, that James IV. made over his gift. Part of the walls

of the King’s Wark may be incorporated in the quaintly gabled old

tenement now occupying the greater part of the site.

The Union of the Crowns

itself, though of great benefit to England in freeing her from the menace

of invasion from Scotland when she engaged in continental war, was very

far indeed from being an unmixed blessing to the people of Leith and

Edinburgh. The removal of the king and court to London meant much loss to

Edinburgh’s merchants, and consequent injury to the trade of Leith. But

that was not their only loss. The absurd claim of the Stuart kings, after

they became British sovereigns, to rule by divine right led to such

tyrannical methods of governing Scotland that Parliament for years

together did not meet. That did much injury to the general merchant, for

the hundred and forty-five Lords and the hundred and sixty Commons who,

with their wives and families, were wont to throng the city for a longer

or shorter period every year, and to bring in their wake much gaiety and

business, did a good deal to stimulate and encourage local trade. As

Edinburgh’s trade was affected so was that of its port of Leith.

But if Leith’s local

trade was injuriously affected by the Union, her overseas trade suffered

still more, and, indeed, was at times almost brought to a standstill.

During the seventeenth century the two countries with which England was

most frequently at war were France and Holland ; but these were the very

countries with which Leith carried on most trade. Through her sovereign,

as King of England, Scotland was, of course, involved in these wars, and

her trade with the enemy forbidden. She was then in the embarrassing

position of having to fight those with whom she wished to be friends, and

of having to pay heavy taxes to carry on wars that ruined her own trade.

The result was that Scotland frequently disregarded the prohibition

against trading with the enemy. We find Leith ships sailing to and from

France and the Low Countries during the French and Dutch wars of the

seventeenth century, to the great indignation of the English, who looked

on the Scots in general, and the Leithers in particular, as they were the

chief overseas traders, as little better than traitors, because the French

favoured them "after the old manner."

But English foreign policy

even in times of peace was often a menace to Leith’s shipping trade.

England’s Navigation Act of 1614 forbade the importation of goods into

England except in English ships. The French Government naturally

retaliated by issuing a similar decree for France. Now such a policy on

the part of France, if carried out against Scotland, would have meant ruin

for many a Leith shipowner. From the reign of James IV. a goodly number of

Leith ships had always been hired and employed by Frenchmen in their own

carrying trade, and would be now laid up for lack of cargoes.

The Scots at once reminded

Marie de Medici, the Queen-Regent of France, that the French still enjoyed

their old trading privileges in Scotland, in spite of the new English

regulations. The Scots had enjoyed the same rights as French subjects in

France from the marriage of Queen Mary with the Dauphin in 1558.

Nor did the Union of the

Crowns bring Leith any recompense of increased trade with England by way

of compensation for this loss of overseas trade, for she was as much shut

out from any share in English foreign and colonial trade as she had been

when the two countries were under separate sovereigns. England persisted

in a policy towards Scotland of always subordinating Scotland’s

interests to her own by shutting her out from any share whatever in those

rights and privileges of trading with the Colonies and Plantations, which

she considered belonged to Englishmen only. King James, who, in his own

way, was ever anxious for the welfare of his Scottish subjects, wished the

two countries to be brought into commercial as well as regal union. The

English commercial classes were bitterly opposed to this scheme, which,

although it failed, was not altogether without good result.

After the Union of the

Crowns there was frequent trouble between the Scots and their English

neighbours, who were much given to piracy and violent outrages at sea. In

1610 nine English pirates were sentenced "to be hangit upon the Sands

of Leyth until they be deid." In the same year thirty more were

doomed to this fate at the same place. The gibbet stood within the

"flood mark," nearly opposite the foot of Constitution Street.

To avoid all such trouble as far as possible, King James issued a

proclamation that the ships of both nations were to carry at their

maintops the flags of St. Andrew and St. George interlaced. It was now

that the Union Jack first made its appearance in Leith harbour. The ships

of Scotland had also to carry at their stern the flag of St. Andrew, while

those of England were to fly, in the same place, that of St. George.

In Scotland up to this time each royal burgh had

protected its own trade area against encroachment by every other burgh,

free or unfree. Now this monopoly of the royal burghs, where all trade was

controlled by the merchant and craft guilds, was about to be broken down,

because it could not be made to fit in with the new ways of trading that

were beginning to come into vogue. The old methods had already broken down

in England, where any one might carry on trade whether he was a member of

the local guilds or not. The first step in this direction in Scotland was

taken in 1597. By this date the Spanish treasure

ships had imported so much gold and silver from America that there had

been a general fall in the value of money throughout Western Europe, and

King James’s income was no longer sufficient for his needs. As a remedy

taxes were imposed on Scottish imports for the first time. From taxes for

revenue purposes only to taxes for the protection of home industries is

but a step. Such a step meant in time the end of mediaeval and the

beginning of modern methods of trading, for from this time the protection

of trade began to be a national instead of a local matter, and was no

longer left to each burgh in its own district.

The step of fostering home industries by heavy

protective duties seems to have been first taken in Leith, where several

new industries were introduced in James’s reign, and began Scotland’s

career as a manufacturing country. This was done by the grant of patents,

or monopolies, to certain merchants, giving to them the sole right of

manufacturing certain articles whose importation from abroad was

prohibited. Under the old system of trading only burgesses of Edinburgh,

who were at the same time members of the merchant guild, could engage in

commerce in our district. Up to this time no Leithers could be merchants, as we understand

the term to-day, although Sir Andrew Wood and the Bartons are often

erroneously described as Leith merchants. They were shipowners, a calling

that no doubt gave them many opportunities for trading, and they could

always find markets abroad for cargoes of their own, either obtained in

foreign ports or by piracy. While merchants might have storehouses and

even booths in Leith, they had to reside in the city or forfeit all their

rights and privileges as merchant burgesses, and become "unfree."

But merchants who obtained monopolies could reside and carry on their

trade wherever they pleased, without being either free burgesses or guild

brothers.

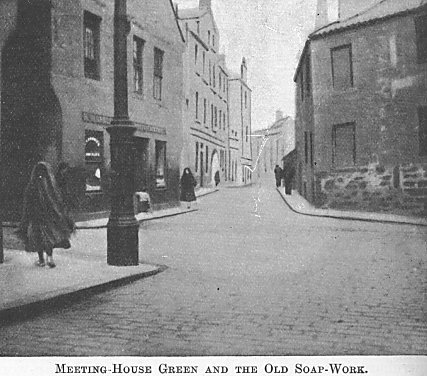

In the wall of the Corporation Buildings, opposite Meeting-house

Green, is a carved stone from the old building which previously

occupied the site, bearing the inscription—

BUILT 1583. T.

J. REBUILT

1800.

This ancient building had been for generations the

Leith Soap-work, which has now removed to Broughton Road. T. J. were the

initials of Thomas Jameson, a noted Leith merchant in his day and

proprietor of this old soap-work at the close of the eighteenth century.

Down to 1619 foreign soap only was used in this country, and was mostly

imported from the Low Countries. In that year Nathaniel Uddart, whose

father had been Provost of Edinburgh, was granted the monopoly of

soapmaking in Scotland for twenty-one years, on condition of paying an

annual duty of £20 to the Crown. He erected "a goodly work" in

Leith to carry on its manufacture. But it does not

seem to have been too prosperous. And indeed that is not surprising, for

in Leith in those days, and everywhere else for that matter, not many

washed every day as they are expected to do now.

Nathaniel

Uddart was one of the most active and enterprising merchants of his time.

The manufacture of soap was the first but not the only industry he

established in Leith. To obtain a supply of oil with which to carry on its

manufacture Uddart received a further patent to trade! in oil obtained

from the whale fishing in Greenland. This led to much trouble with the

English Muscovy Company, trading with Russia through Archangel, then her

only seaport, for at this time she had no possessions on the Baltic coast.

The Muscovy Corn Nathaniel

Uddart was one of the most active and enterprising merchants of his time.

The manufacture of soap was the first but not the only industry he

established in Leith. To obtain a supply of oil with which to carry on its

manufacture Uddart received a further patent to trade! in oil obtained

from the whale fishing in Greenland. This led to much trouble with the

English Muscovy Company, trading with Russia through Archangel, then her

only seaport, for at this time she had no possessions on the Baltic coast.

The Muscovy Corn

pany looked on

the entry of Leith ships into the Arctic Seas as an infringement of their

monopoly, and resisted them with "wild outrages, riots, murder, and

effusion of blood."

Uddart’s patent seems to

have been either recalled or allowed to lapse, for in 1634 a new grant was

made to Patrick Maule of Panmure, "His Majesty’s daily

servitor." Panmure Close, in the Canongate, just below the parish

church, where a large portion of the family mansion still remains,

preserves the memory of this family in our midst. Like Uddart, Maule also

sent ships to the Greenland whale fishing and to Archangel, from which he

imported materials used in the soap factory at Leith; but the oil and

tallow for this purpose were both more extensively and more conveniently

shipped from Danzig and Königsberg, the two chief centres of Leith’s

trade with the Baltic Seas. The manufacture of soap and the whale fishing

were to continue to be two of Leith’s staple industries for the next two

hundred and fifty years. From this time Leith was no longer simply a

trading port. With the soap and oil works of Uddart and Maule she enters

on that career which has made her to-day not only a great seaport but a

busy and prosperous centre of industry as well.

But the departure from the

old methods of trading under the hampering control of the merchant and

trade guilds was only in its infancy, and developed slowly in the

seventeenth century. Indeed it was impossible it could be otherwise. Apart

from the dislocation of trade through England’s wars with France, Spain,

and Holland, in which Scotland was her unwilling partner, with such

troubles as the civil wars of Charles I.’s time, and the misgovernment

and persecutions all through the reign of his son, Charles II., no country

could thrive. Scotland was thus kept in a state of poverty. There was

little money with which to start new industries, and capital was scarcely

more plentiful in Leith than in other parts of the country. The

manufactures introduced by the enterprise of the ever-active Uddart

struggled along rather than progressed, and sailoring, fishing, and

farming the lands immediately around the town were still, as in older

days, the chief occupations of Leith’s inhabitants.

The want of capital with

which to begin and support new industries, and later the disturbing effect

of the civil strife in Charles I. and Cromwell’s time, led to much

unemployment at home. Scotsmen, therefore, as at the close of the wars

between king’s men and queen’s men, still sought fortune abroad in

continental wars.

One of the largest and most

beautiful comets that have ever been chronicled appeared in our northern

sky in the beginning of 1618. Leithers, like other Scotsmen, gazed night

after night with awe and wonder on the blazing messenger, for messenger

they believed it to be.

Ben Jonson, the friend of

Shakespeare, and after him the greatest of the Elizabethan dramatists,

came to Scotland at this very time. During the whole period of this comet

he was residing in Leith in the house of Mr. John Stuart, Water-Bailie,

and owner of the ship, The Post of Leith. Here

he was visited by that eccentric Londoner, John Taylor, the Water Poet,

while on his Penniless Pilgrimage. Taylor had been hospitably entertained

at the King’s Wark by Bernard Lindsay and his good dame Barbara, a Logan

of Coatfield. Jonson wrote a journal of his tour, which, unfortunately for

us to-day, was burnt while in manuscript through his house taking fire,

and thus much valuable information about Leith and his many friends there,

among whom we may number the Nisbets of

Craigentinny, was lost to us. The great Elizabethan must often have

discussed the strange stellar visitant with those friends who knew not

what to make of it.

"The heavens themselves blaze forth

the death of princes," says Shakespeare, and the superstition of the

age afterwards held this unusual visitant to have been a portent of the

Thirty Years’ War that broke out in the same year. In this great

struggle James’s only daughter Elizabeth and her kingdom of Bohemia were

overwhelmed with misfortune. Scotsmen deemed it a patriotic duty to go to

her support. Scotland became a chief recruiting ground for raising levies

to support the Protestant cause in this war championed by Gustavus

Adolphus, the "Lion of the North," and Leith was the chief port

for their embarkation. Now we see the "fighting Wauchopes" of

Niddrie sailing away in command of a company; now a troopship leaves the

Shore with much cheering. Under the brilliant; generalship of the

"Lion of the North," Scotsmen like Sir Patrick Ruthven and the

two Leslies learned soldiering abroad, which they used afterwards with

such skill in Leith that its effects are still plainly visible in the town

to-day. But these wars were a serious drain on the manhood of the country,

and the sorrow they caused finds touching expression in more than one old

song—

"Oh, lang, lang is the

travel to the bonnie Pier o’ Leith,

Oh dreich it is to gang on foot wi’ the snaw

drift in the teeth!

And oh, the cauld wind froze the tear that gather’d in my e’e,

When I gaed there to see my love embark for Germanie."

But the chronic poverty of

the country drove thousands more abroad in pursuit of trade. A great deal

of the foreign trade of Leith, especially with Poland and other lands

bordering the Baltic Sea, was carried on by pedlars, who, when their ships

reached such ports as Danzig, Königsberg, or Stralsund, went round the

country, and especially the village fairs, selling to the peasantry, as

Breton onion-sellers used to do in Leith and Edinburgh before the Great

War, and are now doing again since the arrival of peace. This was one

reason why English merchants opposed King James’s commercial union

between England and Scotland, because the Scots, they declared,

"trade after a meaner sort and condition in foreign parts than we, by

retailing parcels and remnants of cloth and other commodities up and down

the countries, as we cannot do, because of the honour of our country, for

their poverty is ever a spur unto them to make them industrious."

Poland and Eastern Prussia

were the Canada for Scotsmen in those times, and few vessels sailed from

Leith for the Baltic Sea that did not carry emigrants to those lands, as

ocean liners do to Canada from Glasgow to-day. The descendants of those

old Scottish emigrants, like General Mackensen (Mackenzie), were among

Germany’s best soldiers in the Great War.

James Riddle, the successor

of Patrick Maule in carrying on the manufacture of soap in Leith, was the

son of one of those Polanders, as they were called. Riddle’s Close,

whose name has in recent years been changed to Market Street, for over two

hundred and fifty years preserved the name, if not the memory, of this old

Leith merchant.

When James I. set out for

England in 1603 he promised to visit Scotland every three years, but a

period of fourteen years was to pass before his Scottish subjects were to

see him once more among them. The news of his coming caused the greatest

bustle and excitement in Leith and Edinburgh, for it seemed an

impossibility to provide lodging, not to speak of provisions, for the huge

following he was expected to bring with him, and for the nobility and

gentry who would be sure to come to town during his Majesty’s visit.

King James and his nobles travelled on horseback from Berwick to Leith,

from which he made his State entry into Edinburgh.

It was strongly believed

that the main object of this, his first and only visit after the Union,

was to complete the work of establishing Episcopacy in Scotland. The

Leithers, who were sternly Presbyterian, had already had experience of

James’s endeavours to bring the Church of Scotland into line with that

of England in polity and service. King James, even in far-off London, kept

an eye on the doings of the Scottish clergy, and had every one exiled or

imprisoned who opposed his Church policy. In January 1606 six ministers,

including Mr. John Welch, who had married the daughter of John Knox, were

condemned to be banished for life from their beloved land for their

resistance to the king’s arbitrary measures in putting down the Church

of Scotland. They were to sail to the Continent from Leith, where they

stayed with Mr. Morton, the minister of South Leith Parish Church, until

their departure, of which we have a touching description from one of their

contemporaries, that reminds us of another parting long before on the

shore at Miletus.

"The ship being ready,

and many attending their embarking, they fell down upon their knees on the

Long Sands and prayed several times very fervently, moving all the

multitude about to tears in abundance and to lamentation, and after they

had sung the 23rd Psalm, joyfully taking their leave of their brethren and

acquaintances, passed to the ship, and upon the morn, getting a fair wind,

were safely transported and landed in France." Next year Mr. Morton

himself was imprisoned in Edinburgh Castle for an "impertinent

sermon" against Episcopacy, nor, after a year, was he released except

on condition that he should "preach not and goe not to Leith."

The Leith folk felt

themselves confirmed in their convictions regarding the purpose of James’s

visit when a ship arrived in the harbour from London with organs,

paintings, and stained-glass windows to fit up Holyrood Chapel for service

during the king’s stay among them. Indeed these mischievous innovations,

as they held them to be, had been supernaturally foretold by such a

swelling of the sea at Leith that the like had not been seen before for a

hundred years. This abnormal tide was taken as a forewarning of some evil

to come. The "evil to come" was of course afterwards seen to be

James’s choristers with their white surplices, his organs, his

paintings, and idolatrous windows set up in the chapel royal of Holyrood.

Eight years afterwards

Leith had another supernatural warning. On Tuesday, March 29, 1625, one of

the greatest storms on record raged round our coasts. The water in the

harbour overflowed on to the Shore, carrying boats with it, and doing much

damage. "It was taken by all men," says a credulous historian,

"to be a forerunner of some great alteration. And indeed the

following day a sure report was brought hither that the king departit this

life the Lord’s day before," and thus the same kind of portent that

had foretold his visit to Scotland was now held to have been warning of

his death, in accordance with the superstitious beliefs of the age.

James was succeeded by his

son, Charles I., who made his first visit to Scotland in 1633, which was

to begin for Leith the most troubled period of her whole history, a period

which continued for fifty-five years. In honour of the king’s visit a

new pulpit was placed in South Leith Church, and it is believed that the

carved stone, with the royal arms and the letters C. R. for Carolus Rex,

in the front of the church tower facing the Kirkgate, was then built into

the stonework of the church in his honour also. The old sculptured stone

that adorned King James’s Hospital was built into the north face of the

tower in 1822. Besides the two panels containing the royal arms in the

church tower there are within the entrance porch two beautifully carved

stones, one of which, taken from her mansion that once stood in Water

Street, shows the arms of Mary of Guise. The other, showing the arms of

her daughter, Mary Queen of Scots, once adorned the old Tolbooth in the

Tolbooth Wynd, first erected in her reign. Thus we have four original and

consecutive royal arms, from James V. to Charles I., built into the church

tower, two within the structure and two outside. James was succeeded by his

son, Charles I., who made his first visit to Scotland in 1633, which was

to begin for Leith the most troubled period of her whole history, a period

which continued for fifty-five years. In honour of the king’s visit a

new pulpit was placed in South Leith Church, and it is believed that the

carved stone, with the royal arms and the letters C. R. for Carolus Rex,

in the front of the church tower facing the Kirkgate, was then built into

the stonework of the church in his honour also. The old sculptured stone

that adorned King James’s Hospital was built into the north face of the

tower in 1822. Besides the two panels containing the royal arms in the

church tower there are within the entrance porch two beautifully carved

stones, one of which, taken from her mansion that once stood in Water

Street, shows the arms of Mary of Guise. The other, showing the arms of

her daughter, Mary Queen of Scots, once adorned the old Tolbooth in the

Tolbooth Wynd, first erected in her reign. Thus we have four original and

consecutive royal arms, from James V. to Charles I., built into the church

tower, two within the structure and two outside.

The visit of Charles I. in

1633, like that of his father James in 1617, was mainly undertaken with a

view to bringing the Church of Scotland into harmony with that of England

in its form of worship. For this purpose Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury,

drew up a service book to be used in Scottish churches. The introduction

of this service book led to the Jenny Geddes riot and the thawing up of

the National Covenant in February 1638.

The Covenant was sworn to

by the people of South Leith in St. Mary’s Church on Thursday, 12th

April, when the minister of Greyfriars’ read and expounded it. Then

"he gurd the people stand up, hold up thair right hands, and swear

very solemnly, which God blessed with ane very sensible

motion." On Sunday; 22nd, it was similarly sworn to by the folk of

North Leith in the Church of St. Ninian, where their own minister, Mr.

Fairfoul, preached from Revelation,

3rd chapter and 2nd verse, a very fitting text for the occasion. By far

the most interesting of the original copies of the National Covenant is

the one in the Edinburgh Corporation Museum, in which there are over four

thousand signatures, among them that of the second Lord Balmerino, one of

the staunchest upholders of the Kirk of Scotland at this time.

All the work of Charles and

Laud was now undone. The king, determined to secure obedience to his

Church policy by force of arms, marched an army to Berwick for this

purpose. But the Scots captains and troops, who had fought so gallantly

for the Protestant cause on the blood-drenched battlefields of Germany,

came pouring homewards when they heard that Scotland was in danger, and

under Sir Alexander Leslie, his nephew Sir David, and that skilled general

of artillery, Sir Alexander Hamilton— "Dear Sandy," as he was

affectionately and familiarly called—they mustered on Leith Links to the

number of twenty thousand. "Sandy" Hamilton refortified the town

on a new plan. The nobles and their ladies, together with the townsfolk—men,

women, and even children—joined enthusiastically to defend the Kirk and

Covenant by helping to carry the earth of which the walls were composed,

while three shiploads of arms were sent to Leith from Holland for the

equipment of Leslie’s army encamped on the Links.

The stout Sir Patrick

Ruthven, nephew to the grim Lord Ruthven who took so dramatic a part in

the murder of Rizzio, also returned from the wars in Germany to be made

governor of Edinburgh Castle on the king’s side. Ruthven and his family

came to take up their residence in Leith, as did so many of the gentry in

the seventeenth century; but with the exception of Balmerino House, and

one or two survivals in Quality Street and Restalrig, few remains of their

old mansions are to be found among us to-day. The Ruthven family had their

pew in South Leith Church. In 1638 Sir Patrick gifted to the congregation

two communion vessels, which are still in use and which were the work of

that wealthy goldsmith, Gilbert Kirkwood, who was at this very time

absorbed in the building of his new mansion of Pilrig House.

The king sent the Marquis

of Hamilton with a fleet to Leith Roads; but the town, where his own

mother was among the defenders, was so strongly fortified that he dared

not attack it. The strength and power of the Covenanting forces arrayed

against him led King Charles to make terms with the Scots by granting the

liberties they desired, and three years later he came to reside again at

Holyrood. While playing golf on Leith Links news was brought to him of the

terrible Irish massacres of 1641, and shortly afterwards he left Edinburgh

never to return. In the next year the great Civil War between King Charles

and the English Parliament began. Sir Patrick Ruthven, after a heroic

resistance of six months, was forced to surrender Edinburgh Castle to

Leslie and his Covenanting army from the Links.

Then by the terms of the

Solemn League and Covenant, which were sworn to in the two Leith churches

after a solemn fast, just as the inhabitants had formerly sworn to the

National Covenant, the Scottish army under Leslie joined the English

Parliamentary forces against the king, and with them across the Border

went, as chaplain, Mr. Gibson, one of the two ministers of South Leith.

Over the Border, too, went Sir Patrick Ruthven to fight as gallantly for

King Charles as Leslie and the army of the Covenant fought against him.

All through these unhappy years of division and strife "ye Ladie

Riven "and her three daughters were allowed to live quietly and

peacefully in their old Leith mansion, and to worship Sunday after Sunday

in the family pew in "ye loft bewast the pulpit" in the Parish

Church in the Kirkgate.

The story of the Civil War

and the ruthless campaign of Montrose and his savage horde lie apart from

the history of Leith, but the grievous strife of this time was to bring

upon the town darker days than she had ever known.

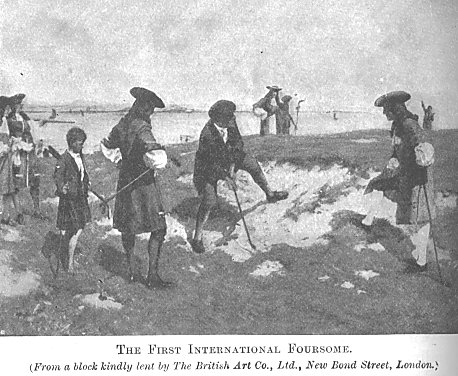

Charles I. at golf on Leith

Links has been made the subject of pictures by Sir John Gilbert, R.A., and

Allan Stewart. Below is a reproduction of another painting by Allan

Stewart, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1919. Its subject is the

foursome on Leith Links in which James II. took part, as related on p.

358.

|