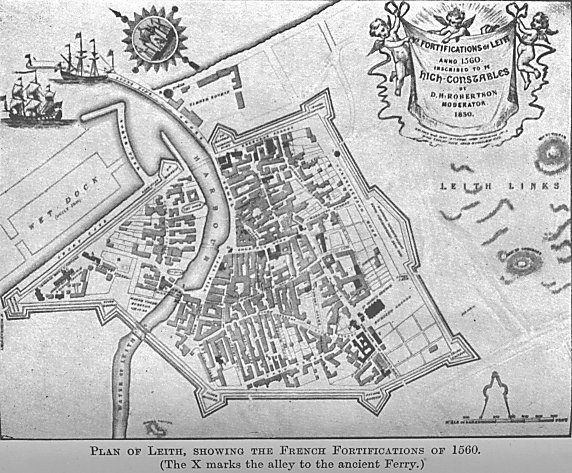

The French commander,

Monsieur D’Essé, soon perceived the strategic importance of Leith, if

fortified, as a stronghold and seaport. It would at once form a safe

retreat should he chance to be defeated by the English, and at the same

time be a gateway by which lie could keep up communication with France, on

which country he was to a large extent dependent for supplies. He

therefore at once set about its fortification. Under his skilled direction

the town was speedily enclosed within strong walls, constructed in

accordance with the most approved principles of military science then

practised on the Continent. Indeed so skilfully had the French constructed

their defensive works that they baffled every attempt of the Scots, aided

by the English, to carry them by assault.

A large and strong bastion,

which bore the name of Ramsay’s Fort, was built immediately north of the

King’s Wark. A similar and equally strong bastion was erected on the

opposite side of the river. These two works formed an adequate defence for

the harbour against attack from the sea. Ramsay’s Fort and its companion

bastion on the north side of the water were built entirely of stone and

were heavily armed with guns, whereas the rampart with which D’Essé

enclosed the town was constructed mostly of earth, where shot from an

enemy’s guns would simply find a grave in which to bury themselves. No

vestiges of D’Essé’s fortifications or of those which succeeded them

in Covenanting times remain to-day. Their memory, however, is still

preserved in the name of Sandport Street, which was so called because a

port or gate in the rampart there led out on to the Short Sands, where the

Custom House now is. The last portion, removed on the construction of the

lower and earlier part of Constitution Street and the erection of the

Assembly Rooms, was known as the Ladies’ Walk, from its having been a

favourite promenade of the Leith belles because of its fine seaward views.

Inchkeith was still

occupied by its English garrison. Whoever held Inchkeith possessed the key

to the Forth in those days as in ours. From that important strategic

position, therefore, the French in Leith now determined to drive the

English out, for not only did they persistently plunder the neighbouring

shores with such vessels as they had, but they were constantly attacking

the shipping passing up and down the Firth. Luckily, however, their powers

of mischief had its limits. They lamented they had no "tall"

ships, meaning ships of war. "Had I a ship like the Mary

Willoughby," wrote the English commander to Somerset, "I

would employ her well. The prizes I have lost would have paid all the

charges of our men here." A ship with Flanders wares, one of the Old

Leith "Wha daur meddle wi’ me?" type that cared naught for the

English garrison on Inchkeith, had just sailed into the harbour under his

very nose, but her whole appearance forbade attack, and hence his Laments

to Somerset. Mary of Guise had been a frequent visitor to Leith since the

arrival of her countrymen in the town. She took so much interest in the

expedition against Inchkeith that she came down to the Shore to see it

embark, and with the fair ladies of her Court waved her encouragement and

wished them a pleasant trip on the Forth as they set out on their venture.

After a prolonged and fierce fight the English commander was slain, when

the garrison surrendered and the expedition returned in triumph to the

harbour.

By the Treaty of Boulogne

in 1550 war between England and France came to an end, and Scotland was

included in the peace. Such English garrisons as still remained in

Scotland now withdrew to their own country, but the French refused to

return overseas. It now seemed as if Scotland had exchanged the domination

of England for that of France, and would eventually become a mere French

province. This feeling was intensified when Queen Mary was married to

Francis II. in 1558. The French had long outstayed their welcome. The

country was thawing more and more to the side of the Reformers, who had

repeatedly demanded from the queen-regent that her countrymen should

depart "furth the kingdom." This she

refused, and both sides then prepared to settle the dispute by force of

arms.

As the Governor of

Edinburgh Castle refused to have any dealings either with Mary of Guise

and the French, or with the Lords of the Congregation, as the Protestant

leaders were now called, the queen-regent, feeling herself unsafe in

Holyrood, sought protection with the French garrison behind the strong

defences of Leith. Here she built for herself a mansion in the Rotten Row

which stood between Quality Lane and the modern Mary of Guise Buildings.

This once royal mansion was demolished in the early eighteenth century,

while an immediately adjacent building of the same period long known as

"Mary of Guise House," which may, indeed, have been part of the

queen-regent’s residence, was removed in 1878.

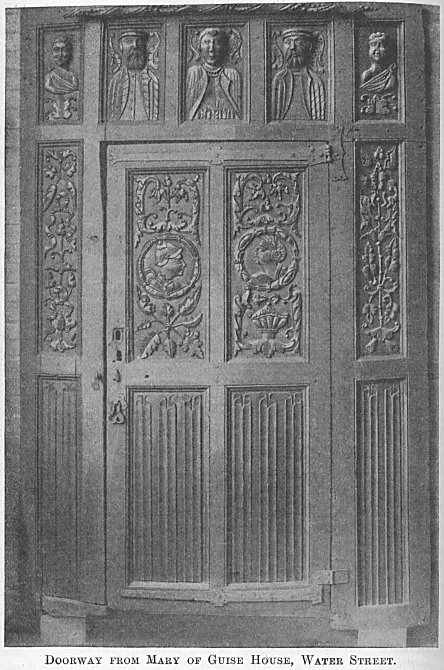

Some

interesting relics of these buildings have been preserved. One is a

beautifully carved stone, having the Guise arms quartered with those of

Scotland, which once adorned the front of Mary of Guise’s house and is

now built into the vestibule of South Leith Church. Two others, a finely

carved oak door and a window frame, are in the safe keeping of the

Antiquarian Museum in Edinburgh. Unfortunately only the lower part of the

window frame has been preserved. It differs from those now in use in

having wooden panels instead of glass in the lower sash, as all windows in

Leith and Edinburgh, even those of Holyrood Palace, had down to the middle

of the seventeenth century, when glass was less plentiful than now because

much more expensive. Such a window may still be seen in Baile Macmorran’s

house in Riddle’s Close, Lawnmarket.

Some

interesting relics of these buildings have been preserved. One is a

beautifully carved stone, having the Guise arms quartered with those of

Scotland, which once adorned the front of Mary of Guise’s house and is

now built into the vestibule of South Leith Church. Two others, a finely

carved oak door and a window frame, are in the safe keeping of the

Antiquarian Museum in Edinburgh. Unfortunately only the lower part of the

window frame has been preserved. It differs from those now in use in

having wooden panels instead of glass in the lower sash, as all windows in

Leith and Edinburgh, even those of Holyrood Palace, had down to the middle

of the seventeenth century, when glass was less plentiful than now because

much more expensive. Such a window may still be seen in Baile Macmorran’s

house in Riddle’s Close, Lawnmarket.

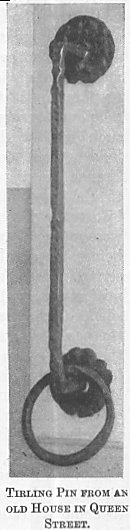

The door giving entry to

Mary of Guise’s house had neither bell nor knocker, but was provided

with a pin or risp, of which a picture of one from an old house in Leith

is given below. No hero  in

the old ballads ever came to his lady love’s door but he "tirled at

the pin." Tirling pins are still commemorated in the old rhyme,

in

the old ballads ever came to his lady love’s door but he "tirled at

the pin." Tirling pins are still commemorated in the old rhyme,

"Tirl the pin, peep in,

Lift the latch, and walk in."

There is a tirling pin on

the kitchen door of Pilrig House, and one has been placed on the door of

the Cannonball House, on the Castle Hill.

With the queen-regent in

Leith were few Scots of note save the far-seeing Maitland of Lethington,

who before long deserted her to join the Reformers, and the wayward and

unstable Sir Robert Logan of Restalrig. The great majority had joined the

Lords of the Congregation, who sent a messenger to Leith to summon the

town by sound of trumpet to surrender within the space of twelve hours.

The trumpeter’s blast, of course, was ignored, and war then began in

earnest. The French troops in Leith numbered just over three thousand men,

but they were all trained veterans who had seen much service in

continental wars. Moreover, they were admirably led, for their commander,

Monsieur D’Oysel, was a man of the greatest courage, and skilled in the

art of war. He felt himself more than a match for the leaders of the

Congregation and their undisciplined and untrained troops. The latter had

no artillery worth the name, and that fact made it impossible for them to

conduct a siege with any hope of success.

After several petty

skirmishes had taken place in which the French were invariably the

victors, the leaders of the Congregation resolved to carry the town by

assault, and marched against it with a force of twelve thousand men.

Scaling ladders for mounting the walls had been prepared in St. Giles’

Church, which led the more strictly religious to predict that nothing but

evil would follow such unholy doings. Their fears proved true. The ladders

were found to be much too short; and the French making a sudden sally, the

besiegers fled back to the city in the greatest disorder. The Protestant

leaders having no money wherewith to pay their men were reduced to coining

their "cupboard" plate, but before this could be done many of

their men had deserted. The French in Leith, hearing of this further

misfortune, sallied out from the town, attacked and silenced a battery of

guns on the Calton Hill, and chased the panic-stricken enemy even into the

city itself, where they made such a fray that all was disorder and uproar

for two hours. They then returned in triumph to Leith laden with plunder,

and were joyfully received by the queen-regent, who had seated herself

upon the ramparts to welcome their victorious return.

Misfortunes, according to

the proverb, never come singly. Nothing at this time seemed to escape the

vigilance of the French. A convoy of provisions was to come to Edinburgh

by the coast road from Musselburgh in the grey light of early morning.

Now, as the long-expected French ships with supplies had not yet arrived

in Leith, indeed were never to arrive, there was nothing the poor Leithers

and the French stood more in need of than provisions.

"Soldiers," exclaimed D’Oysel, addressing his hungry troops,

"we can have ample supplies of food and drink if we have but the

courage to take them." This was welcome news, and the French troops

were at once eager for the venture. D’Oysel embarked a chosen body of

his men in boats, to escape detection, and sent them along the coast to

lie in ambush at a point on the Figgate Whins, near Restairig, where the

convoy must pass. The troops sent to protect the provisions were

unexpectedly set upon and driven in headlong flight into the city, while

the convoy was compelled to change its course for Leith.

The poor Leithers must have

had a sorry time with over three thousand French troops billeted on them.

These occupied the best rooms in their houses and had the first share of

any food that was going. But the Leithers were to have a sorrier time

before the siege was over, for it was as yet not well begun. Fortune was

to prove unkind to the brave and chivalrous D’Oysel. Queen Elizabeth

made a treaty, the Treaty of Berwick, with the leaders of the

Congregation, by which she agreed to help them with men, money, and a

fleet to drive out the French and to establish Protestantism in Scotland.

In accordance with the

terms of this treaty an English fleet under Admiral Winter arrived in the

Forth. It had been delayed by storms, but the same storm that had detained

Winter’s ships had also driven a French fleet on its way to Leith to

ruin on the Danish coast. Two of these French ships, however, richly laden

with much-needed stores, eluded the English vessels and came to anchor off

the mouth of the harbour under the protection of the French guns. But

misfortune was yet to overtake them, for while their officers, in the

belief that their ships were perfectly safe, were supping with the

queen-regent, a Leith sailorman, Andrew Sandes by name and one of a family

of noted Leith mariners, with some kindred spirits, all apparently of

Protestant leanings and all in league with the English admiral, stealthily

rowed out to the Roads in the darkness of the winter night, boarded the

two French ships, and, after a sharp conflict, carried them off to the

English fleet.

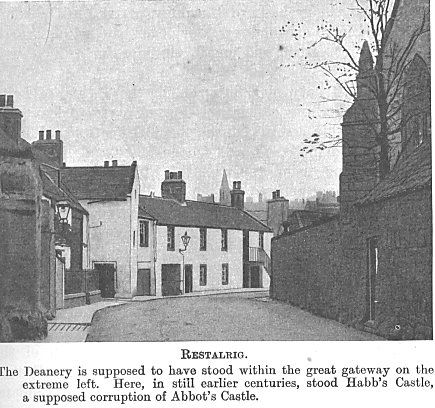

Two months after Elizabeth’s

fleet had begun to blockade Leith from the sea, Lord Grey and the English

army joined the Scots in enclosing it on the land side. The English

commander made himself comfortable in the deanery at Restalrig while his

men lay encamped between that village and the Links. Whether Scotland was

to remain Catholic or become Protestant was to depend upon the fate of

Leith. The English troops had scarcely arrived, when the French,

undeterred by their superior numbers, sallied out from Leith, and,

crossing the Links, took possession of the heights of Hawkhill, where a

fierce but unequal contest raged for several hours. The French were at

last forced to retreat, and withdrew behind their ramparts.

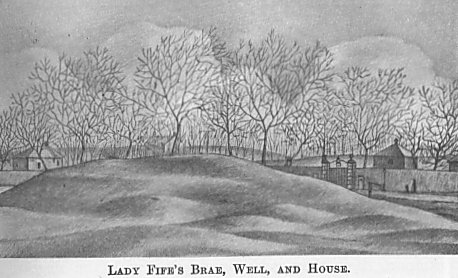

The English siege trenches

gradually drew closer to the town. The French, to retard the progress of

the works, made frequent sorties and did as much damage as they could

before they again retired. In this way many a fierce and hotly contested

skirmish took place on the Links midway between the two hostile camps. But

such desultory fighting did not bring the capture of the town and the

expulsion of the French any nearer. Accordingly, the English abandoned

their position on the Hawkhill and erected two huge mounds on the Links on

which to mount their guns. These two mounds—Mount Pelham, now Lady Fife’s

Brae, after the Countess of Fife, whose mansion of Hermitage House stood

close by, and Mount Somerset, so well known to-day as the Giant’s Brae—were

named after their respective captains of artillery. The English raised a

third—Mount Falcon—in the neighbourhood of Bowling Green Street, and

then, in conjunction with the fleet, began a fierce bombardment of the

town. The steeple of St. Anthony’s Hospital Church was shot down, and so

were the choir and tower of St. Mary’s, for they stood directly in the

line of fire from Mount Somerset. The guns of Mount Falcon swept the Shore

from end to end, so that to pass that way was to run the risk of almost

certain death.

The bombardment went on for

several weeks, yet the French showed no sign of surrender, nor had any

breach been made in the walls. Many of the inhabitants were killed, and

although the ramparts remained unbreached, much damage was done in the

town. One night in April 1560, just after supper, a great fire broke out

in the neighbourhood of the Sheriff Brae, and raged among the

timber-fronted houses throughout the whole night. The glare of the fire

was seen for miles around, and the English prevented any attempt of the

townsfolk to extinguish it by pouring upon the spot an incessant fusilade

from their guns. Mary of Guise watched the progress of the fire from the

Castle ramparts. To her laments over this misfortune to her loyal

Frenchmen the unfeeling Governor rudely replied, "Indeed, madam,

since it seems beyond the power of man to drive out the beggarly French,

God Him self is taking the matter in hand."

The blockade now began to

tell upon the besieged, who suffered much from famine, and were reduced to

consuming horse flesh and the bodies of animals of a much less wholesome

kind. But the French were evidently great sports, for they were in no way

downhearted, and fought none the less gallantly in spite of the strange

meats on which they fed. They were wont to rag the English by politely

asking them from the ramparts how they were progressing with the siege of

Restalrig. Queen Elizabeth, too, and her ministers, seeing little or no

result for their large outlay, although the siege had lasted for months,

began to hint that Lord Grey must be finding the deanery at Restairig

"a very sweet lodging." It was certainly exasperating to be

paying £20,000 a month in what seemed a vain endeavour to drive out a few

thousand ragged and hall-starved Frenchmen.

Provoked by the stubborn

defence and the jibes of the Frenchmen, not to speak of the whispers from

London, the fleet and the army determined to make another grand assault on

the town, and spoke boastfully of how, on this occasion, they would carry

all before them. But they failed as ignominiously as before, for the

besieged, aided by their womenfolk and even their children, made so

spirited a resistance that the besiegers were hurled headlong from the

ramparts, leaving over one thousand killed and wounded around the walls.

The

English had attempted to drive out the French from Leith by force, and had

failed. Queen Elizabeth resolved to see what diplomacy could do, and a

truce was made. Just at this stage Mary of Guise died. She had been long

suffering from an incurable disease, and had been allowed to retire

to Edinburgh Castle, from which she daily looked towards Leith to see if

the banner of her faithful and gallant Frenchmen still floated over the

beleaguered town. The road to peace was made easier by her death. The

English were tired of the siege, and when Queen Elizabeth’s secretary,

Sir William Cecil, afterwards the great Lord Burghley, arrived in the camp

at Restalrig to arrange terms of peace, the soldiers made all the guns,

great and small, thunder forth their welcome.

The

English had attempted to drive out the French from Leith by force, and had

failed. Queen Elizabeth resolved to see what diplomacy could do, and a

truce was made. Just at this stage Mary of Guise died. She had been long

suffering from an incurable disease, and had been allowed to retire

to Edinburgh Castle, from which she daily looked towards Leith to see if

the banner of her faithful and gallant Frenchmen still floated over the

beleaguered town. The road to peace was made easier by her death. The

English were tired of the siege, and when Queen Elizabeth’s secretary,

Sir William Cecil, afterwards the great Lord Burghley, arrived in the camp

at Restalrig to arrange terms of peace, the soldiers made all the guns,

great and small, thunder forth their welcome.

By the Treaty of Edinburgh, or the Treaty of Leith as

it is sometimes called, the French were to leave the country

within twenty days, the fortifications of Leith were to be demolished, and

Queen Mary and Francis II. were to cease using the arms of England. But

Queen Mary in France refused to sign the Treaty of Edinburgh, an act for

which Elizabeth never forgave her. To the siege of Leith, then, is due in

part the lifelong enmity that Elizabeth cherished toward Queen Mary. In

resulting in the Treaty of Edinburgh the siege of Leith forms a great

central landmark in the history of our country. The departure of the

French marks the fall of the Catholic Church in Scotland, and the end of

the ancient Franco-Scottish Alliance. The triumph of the leaders of the

Congregation was the triumph of Protestantism, and the beginning of that

union with England which gave rise to the kingdom of Great Britain, and

has helped to make her the great world Power she is to-day.