|

HERTFORD arrived in the

Forth on his errand of destruction on the afternoon of Saturday, May 4,

1544. The Regent Arran (son to him who led James IV.’s navy to France)

and Cardinal Beaton had got wind of the expedition a few days before, but

too late to muster forces for effective resistance, and they made little

or no use of those they had. They, however, warned all the inhabitants of

the towns on the south shore of the Forth to fortify their towns with

trenches to resist "the Englishe mennis navye," which those of

Leith did. The people of Edinburgh and Leith gathered at every point of

vantage to gaze on the great fleet of two hundred ships as they sailed up

the Firth and came to anchor above Inchkeith.

Next morning the English

army disembarked on the shore under the shadow of Wardie Tower, which had

been built in the year 1500 by the Laird of Inverleith to defend his lands

against the English; but on this occasion, like the Scottish leaders,

Wardie Tower did nothing to oppose the enemy’s landing. The English then

marched in three divisions to the Water of Leith, near Bonnington Mill,

where their passage was disputed by some Scottish troops under Arran and

Beaton. The Scots made but a feeble resistance, however, and were easily

repulsed. Crossing the stream, the English then turned their steps towards

Leith, whose early capture was necessary that they might bring their ships

into its harbour for the landing of guns and stores. They were already

bringing their larger ships into Newhaven.

John Knox, who was much

given to the use of exaggerated language, gives a graphic picture of the

English entry into Leith that suggests a sudden surprise and flight.

According to Knox the English marched into the town, where they found

"the tables covered, the dennarts prepared," and such abundance

of wine and victuals as one could not find in any other town of the same

size either in Scotland or England. Now it is hardly likely that the

Leithers would prepare their Sunday dinners with the English marching

towards their gates. In reality, save the defenders, all the inhabitants

had fled from the town before the English arrived. But these same

defenders did not allow the enemy the easy walk-over Knox would lead us to

suppose. "We captured then by force," reports Hertford to his

much gratified master, "the entry to the town of Leith, which was

stoutly defended."

The crowd of fugitives, the

stronger helping the more feeble and the sick, would make their way as

best they could to the wilderness of swamp and morass that, for the

greater part of the way, then extended between Duddingston and Gogar,

where none could find them save those who knew the straggling and perilous

paths by which their retreats alone could be reached. English invasion had

made the folk of Leith familiar with these treacherous wastes, where they

could remain in comparative safety until the enemy had taken their

departure. From the large amount of plunder the English carried away from

the town it is evident the Leithers

had fled in haste, and had had no time to take with them more than some

oatmeal, perhaps, and a few cooking utensils.

The English found two

goodly ships in the harbour —the Salamander, given to James V. by

the French king on his marriage with the ill-fated Madeleine, and the Unicorn,

which had been built in Leith or Newhaven. Whether the English found

in the town all the sumptuous fare Knox pictures for us Hertford does not

say, but that they captured a wealth of booty they had never anticipated

is certain. "The town was found fuller of riches than we expected any

Scottish town to have been," reported the English admiral. In fact,

the enemy captured booty in Leith to the value of £100,000 of our money—an

amount of wealth that seems to contradict much of what we are generally

told of Scotland’s poverty in those troublous times.

During the whole week they

were encamped in Leith the English gave themselves up to the work of

destruction. Edinburgh was given over to the torch. For three days and

nights it blazed, and, being a city set on a hill, its burning was an

awesome sight to behold. Holyrood, too, went up in flames; and with it was

destroyed Restalrig and its tower above the loch, Pilrig, Newhaven, and

the tower of the Laird of Inverleith on Wardie brow. Not a village in the

neighbourhood, not a farm steading, not even a cottage was left unscathed.

Meanwhile the English fleet had not been idle, for not a harbour, not a

ship, not even a boat was left undestroyed on either side of the Firth

from Stirling to the ocean.

The invaders now prepared

to evacuate Leith, but before doing so they indulged in the same wanton

destruction that had characterized their whole invasion.

They broke down the pier of

Leith and burnt every stick of it. They took away the two goodly ships,

the Salamander and the Unicorn, ballasting them with cannon

shot from the King’s Wark. They then sent away their ships not merely

laden but, to use their own expression, cumbered with booty, and resolved

to return homewards themselves by land. The night before their departure

from Leith they held a grand carnival of destruction by burning every

house in the town. Next morning they set off across the Links on their

homeward march, passing Restalrig, now a blackened ruin, and then marched

away eastwards by the Fishwives’ Causeway, leaving a line of smoking

towns, villages, and farms to mark their route.

Such were some of the

things Leith saw and suffered in those old unhappy days. We can only

partly realize the grief and terror of the townsfolk as they sought refuge

from the cruelties and outrages of Hertford’s savage soldiery amid the

wastes and recesses around Arthur’s Seat and the country farther west.

Their suffering and misery are to a certain extent suggested to us in that

dispatch of Hertford’s detailing his fell work, which proved such

pleasant reading to Henry VIII. In this document Hertford tells us how,

standing with his officers upon the Calton Hill to view the burning city,

he heard the women and children in the valley beyond, as they witnessed

the destruction of their homes, bewailing their woeful state. On the

departure of the invader those from Leith stole back again to the ruined

town. Until their houses were repaired they found shelter in St. Mary’s

Church, which, strangely enough, had escaped the flames.

The Leith sailormen knew

all along of the mighty fleet Hertford was assembling in the Tyne and,

guessing its purpose, had discreetly kept themselves and their ships out

of harm’s way. They now returned, however, and determined that England

should pay towards repairing the great loss the Port had sustained at her

hands. Hertford’s fleet had now sailed to the Channel, where it was

sorely needed for service against France, and was not likely to return

until peace was made. Led by John Barton with the Mary Willoughby, the

Lion, and other ships, the Leith mariners hung along the English

coast for the next four or five months and worked their will upon the

English, Dutch, and Flemish shipping—for the latter countries, under the

rule of Mary of Hungary, were for the time being Henry’s allies against

France. The Leith seamen during the war were thus shut out from trading

with the Netherlands, and were now voyaging to Hamburg and other Hansard

ports instead. "It would be an easy thing to lighten them by the way,

either going or coming," wrote one of Henry’s numerous spies; but

the English king had his hands full in France, and so the Leithers, for

the time at least, had command of the North Sea.

Newcastle was sorely

stricken with plague, and could send neither ship, boat, nor mariner to

oppose the Leithers. Hull, Yarmouth, and other east coast ports sent

urgent appeals to Henry. "If we might have help here," they

lamented, "the Scots should not long keep the seas. No man that sails

by the coast can escape them, for they cannot be meddled with." Their

only consolation was a message to help themselves as the Channel ports

did. But their desire for revenge made those east coast towns importunate,

and so another appeal was made to their sovereign lord. "They are

desperate merchants of Leith and Edinburgh, who, having lost almost their

whole substance at the army’s late being

in Scotland, seek adventures to recover something. They have taken many

Hollanders, and with such as they take of ours wax wealthy again. Six of

your Majesty’s ships are a match for sixteen of them. Sorry are we that

they route after this sort upon the seas." But his Majesty told his

loving subjects that if the Scots could be so easily beaten that was all

the more reason why they should attempt it themselves. And so the

"desperate Leith and Edinburgh merchants" continued to

"route" upon the English seas because no mariner of the

"auld enemy" dared say them nay.

Henry VIII. died early in

1547; but his death brought no change in the English policy towards

Scotland, except for the worse, if that were possible, for Hertford, now

Duke of Somerset, in his endeavours to compel the Scots to marry their

little Queen Mary to Edward VI., surpassed even Henry VIII. in merciless

and savage cruelty, as Leith was soon to know. He invaded Scotland once

more, this time by land. The bale-fires blazed forth the news of his

having crossed the Border. At Pinkie, near Musselburgh, he inflicted on

the Scots army under Arran such an overwhelming defeat that for long years

after the name of Black Saturday, given to the anniversary of the fight,

reminded Scotland of one of the most disastrous days in her annals.

The craftsmen and merchant

burgesses of Edinburgh, "the sons of heroes slain at Flodden,"

had again nobly come forward in defence of queen and country, and nearly

four hundred widows were left to mourn their husbands sent to their long

last home at Pinkie Cleuch. There, too, fell Robert Monypenny, the Laird

of Pilrig; but who else from Leith, save the Laird of Restairig, took part

with Monypenny in this most disastrous fight we cannot tell. Luckily for

the Leith sailormen, they had set out on the autumn voyaging before the

invasion took place, for Somerset was accompanied by a fleet of transports

and war vessels that came to anchor off the mouth of the harbour.

The day after the battle

the English marched straight along the shore to Leith, "the which we

found all desolate, for not a soul did we find in the town." The

Leithers, like the other inhabitants of the district, had been ordered to

betake themselves and their gear within the shelter of the walls of

Edinburgh. If the English had anticipated again enriching themselves with

stores of loot from Leith they were to be hugely disappointed. Except some

thirteen odd vessels, most of which were old and ruinous, there was little

else to be found, "for as much of other things as could well be

carried the inhabitants overnight had carried off with them," writes

one who accompanied the expedition. What a strange procession they must

have formed—the men, women, and children of Leith—as they toiled

towards Edinburgh, bent and perspiring under their load of household gear.

"My Lord Somerset and most of our horsemen were lodged in the

town," while the rest of the army, in full view of their fleet riding

at anchor in the Roads, lay encamped on the Links and on the stubble

fields stretching away towards Lochend and Holyrood.

The English lay around

Leith for a week. They struck their camp on the following Saturday, but

Somerset, "mynding before with recompence sumwhat to reward one

Barton, that had plaid an untrue part, commanded that overnight his house

should be set afyr." This was John Barton, whom we have already seen

achieving so much fame with his ships, the Lion and the Mary

Willoughby. His "untrue part" was that he bad been devotedly

loyal in serving his country, as all the Leith sailormen were in those

days, when the shiftiness and double-dealing of the nobles who favoured

the English cause had made the name of Scot a byword in England.

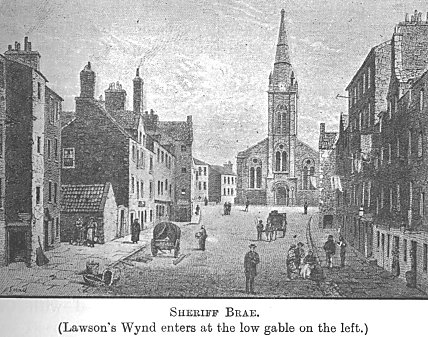

We do not know where John

Barton’s house was situated in Leith. As he was now the chief member of

his family residing in the town, he had in all likelihood heired that of

his grandfather, who had built his house in the Sheriff Brae, close by the

residence of his old friend and fellow mariner, John Lawson of Lawson’s

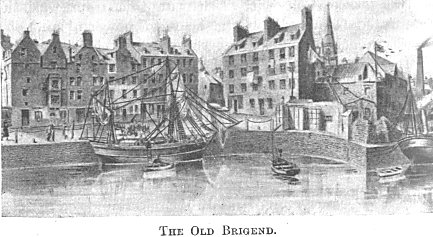

Wynd, which was almost opposite the Old Brigend. In setting the torch to

Barton’s house the English soldiers, in their mischievous zeal, fired

all the town besides. "Six great ships lying in the haven

there," says the chronicler who accompanied the army, "that for

age and decay were not so apt for use, were then also set on fire, which

all the night with great flame did burn very solemnly." Leaving the

ships and the town in flames behind them, the English left Leith early

next morning. The Castle gave them a few parting shots as they crossed the

Links towards Lochend and Restalrig on their way to the Border. The

English fleet continued in the Roads for some time longer, to complete

their work of destroying the harbours and shipping along the coast. Then,

leaving garrisons behind them on Inchkeith and Inchcolm, the English ships

sailed away to the south.

Hertford gained nothing by

the slaughter of Pinkie and outrages like the burnings of Leith, for the

little Queen Mary was sent to France, where she eventually married the

Dauphin, who became king as Francis II. Leith suffered as she did because

Scotland was divided into factions, and thus no effective resistance could

be made against the enemy. There were two great parties— the party

favourable to France, which included the great mass of the people, and

held strongly to the Catholic Church; and the party desirous of closer

relations with England, and which, as England was now a Protestant

country, became more and more identified with the doctrines of the

Reformation.

But as yet those who

favoured Protestantism in Scotland ran great risk of persecution and even

death. Leith was not only destined to be the scene of the final triumph of

the Reformers over their opponents, but was also to aid largely in

spreading the new doctrines that were to overthrow the ancient Church. The

converts to the new teaching were at first known in Scotland as Lutherans.

Leith sailormen and Edinburgh merchants sailing to the Baltic ports, and

especially to Danzig, an early centre of the Lutheran Church, were among

the first to become familiar with its teaching. It was chiefly through the

traders of Leith and St. Andrews that Luther’s books and copies of

Tyndale’s New Testament, carefully concealed in bales of merchandise,

were imported into Scotland in spite of all the prohibitions against them.

In this way Leith and Edinburgh made early acquaintance with Protestant

doctrines.

The spread of the new

teaching among the seafaring folk of Leith is shown in 1534, the year when

David Straitoun and Norman Gourlay were executed as heretics at the Cross

of Greenside, opposite Picardy Place. In that year Adam Deas, shipwright

in North Leith, and Henry Cairns, a skipper, are cited to appear before

the Archbishop of St. Andrews. What became of Deas does not appear, but

Henry Cairns prudently went off to sea, and was denounced as fugitive and

heretic with blast of trumpet on the Shore, the chief place of public

resort both for townsmen and foreign traders, who would carry the news

overseas.

The most noted sufferer for

the Protestant faith having association with Leith at this time was the

celebrated George Wishart, the most powerful and eloquent preacher of his

day. On a Sunday in the middle of December 1545 he preached in Leith on

the Parable of the Sower. No memory of Wishart’s friends, or of their

place of abode, has survived in Leith, but this gathering of sympathizers,

so desirous to hear him discourse to them, and their assurance that

nothing was to be feared from the inhabitants, suggest that the new

religion had numerous supporters in the town.

Every year, as June and

July came round, companies of pilgrims had for long centuries been

accustomed to embark at the Shore to voyage by way of Bruges to the shrine

of that most popular of saints in Western Europe, St. James of Compostella,

in Spain, and to return in September with their clam shells in token of

their pilgrimage. Of these pilgrimages there is still a memorial over the

doorway numbered 150 High Street, Edinburgh, marking where once stood the

Clam Shell Turnpike. But now men like Patrick Hamilton, the first Scottish

martyr, whose father had been Provost of Edinburgh in 1515, began to

voyage to Danzig and other Baltic ports to see and hear Martin Luther at

Wittenberg.

The Old Brigend was left in

ruins by Hertford’s troops after their victory at Pinkie. With that

woeful battle may be associated the weird story of Bessie Dunlop, who met

the ghost of Tom Reid, slain in Pinkie fight, by the waters of Lochend.

Tom’s ghost conferred upon Bessie the magic power which brought her to

the stake as a witch in 1576. During Bessie’s uncanny interview a great

cavalcade of the fairies swept past, with loud jingle of bridle bells.

They seemed to ride into the loch and so disappear.

|