|

WITH the accession of the

haughty and imperious Henry VIII. to the English throne in 1509 the

friendly relations which had existed between Scotland and England since

the marriage of James IV. and Margaret Tudor soon became strained. The

state of affairs on the Continent was partly to blame for this. There Pope

Julius II. had formed the Holy League with Venice, Spain, the Emperor

Maximilian, and Henry VIII. against France. James could hardly with honour

to himself remain neutral when the ancient ally of Scotland was thus being

attacked on all sides, more especially as he well knew—and the events of

history were to justify his belief---—that,

if Henry succeeded in France, Scotland would be the next to suffer from

his ambition.

And besides, James himself

had several causes of quarrel with Henry, only one of which concerns our

story of Leith. This was the attack by the Howards on Andrew Barton and

his two ships in time of peace. It was just at this time that De la Motte,

the French ambassador, arrived with his queen’s appeal for help.

bringing with him into Leith seven English ships captured at sea. Three

months later Robert Barton brought in thirteen more. War inevitably

followed. James determined to assist France by leading an army across the

Border and sending his now powerful fleet to cooperate with that of France

against England in the Channel.

On the outbreak of war the

command of the fleet, as we have seen, was not given to a real seaman like

Sir Andrew Wood or Robert Barton, but to the Earl of Arran, for in feudal

times the high officers of State were chosen from among the great nobles.

Robert Barton sailed under Arran as captain of the Lion, while his

brother John went as commander of the Margaret, but died on the

voyage before the fleet reached France. The ships of the fleet were

completely equipped in every way, their complement of men including

chaplains and surgeons just as those of warships do to-day.

We can imagine the stir and

excitement in Leith when the ships sailed away, since all the sailormen and

gunners of Leith and Newhaven were aboard. So was King James, for to show

his interest in the expedition he had resolved to sail in the Great

Michael as far as the May Island. The children and the womenfolk, the

old and the feeble, crowded the pier and the beach to watch the fleet as

it sailed away, little dreaming that as the ships, their pride and their

boast, one after another, disappeared beyond the horizon they had seen the

most of them for the last time. On the king’s return to Leith, Arran,

instead of steering direct for France, for some unaccountable reason went

North-about and arrived in France too late to have any influence on the

war. From this date the navy of James IV., built at so great a cost and

constructed almost entirely by the people of Leith and Newhaven,

disappears from history, and seems to have been sold out of the service,

for during the long and troubled minority of James V. little patriotism

was left in the land.

Meanwhile the great army of

James was gathering at the Standand Stane on the Burgh Muir, over which

the streets and villas of Morningside are now built. This "standand

stane" has been placed upon, the wall enclosing the grounds of

Morningside Parish Church, and is now known as the "Bore Stone."

James and his army were no more successful than the fleet, for at Flodden

they met with such disastrous defeat that the sorrow of it even yet echoes

mournfully in song and story. Local tradition records how nobly the

burgesses of Edinburgh fought and died around their king in the gloom of

that fatal September evening on Flodden Edge, and how great was the sorrow

the dark tidings of the disaster brought her.

But what of Leith?

"Tradition, legend, tune, and song" record the part towns like

Edinburgh, Selkirk, and Hawick played in this much-storied battle; but how

many Leithers, if asked, could tell what share their town took in the

Flodden campaign? And yet, when we turn to the accounts for the king’s

ships, the story of Leith’s part is at once revealed. The men of Leith

and Newhaven, as one might have guessed, were with the fleet; for their

country has never called when they have not heard. Their very names are

all set down, and run to hundreds; First on the list come the Bartons, of

whom there were no fewer than seven, followed by their relations the

Edmonstones and the Kers, who, with the Richardsons, lived in North Leith.

The tragic and untimely

death of James IV. at Flodden was nowhere more lamented than in Leith, for

in no part of the country had that gay and romantic monarch been better

known and more loved. His interest in his ships and dockyards had brought

him almost daily to the town, where he was a frequent and welcome visitor

at the homes of his more noted sea-captains, Sir Andrew Wood, the Bartons,

the Logans, Will Merrymouth, and Will Brownhill. Never again was any king

of Scotland to have such frequent and friendly association with Leith as

James IV. had had. Under his wise and peaceful rule the town had grown and

prospered, but its prominence in national affairs was not due to its size,

which was small, but to its harbour, then the most important in the

country, and to its sailormen, whose courage and daring were held in

wholesome dread wherever their flag was known.

The truth of the chronicler

Fordoun’s almost prophetic utterance, "Woe to the land when the

king is a child," was to be brought home to the people of Leith

during the long minority of James V. in a way never before experienced

even in unruly Scotland. The wayward Earl of Arran in the summer of 1513

returned with three ships of the fleet he had so leisurely led to France,

two of them being the Margaret and the James. The Great

Michael and the others were sold to the French king, and Leith saw

them no more. The Leith sailor-men on their return complained bitterly of

their treatment at the hands of the French, who, no doubt, felt keenly the

tardy arrival of Arran, for the war had gone against their king, Louis

XII.

Arran became Provost of

Edinburgh, and was at the same time head of the King’s Council. In a

dispute between the merchant burgesses of Edinburgh and the Leithers, led

by Robert Barton, about the sale of a cargo of timber brought by a Dutch

ship to the Shore, Arran, in an evil hour for himself, and to the towering

wrath of the Edinburgh burgesses, sided with the Leithers, who, to say

truth, had ignored any rights of the burgesses in the matter. The

Edinburgh merchants, however, soon found occasion

for revenge. In the great street fight between Arran and Angus and their

followers, known to fame as "Cleanse the Causeway," the burgesses

took the side of Angus, and Arran and his son only saved themselves by

mounting a pack-horse that had come into the city with coals, and riding

through the shallows of the Nor’ Loch for their lives.

It was impossible that trade could

flourish amid the lawlessness and consequent insecurity that ensued when

rulers in the State like Angus and Arran led the way in stirring up

turmoil and strife. It was decreed that no Hamilton or Douglas should

occupy the provost’s chair. Leith then, for the first and only time,

supplied the city with her chief magistrate in the person of Robert Logan

of Coatfield, who was granted 100 merks in addition to his ordinary fee,

that he might employ four armed men to carry halberds before him,

"because the warld is brukle (unsettled) and troublous."

It was now that Henry VIII. began a

policy of "frightfulness" against Scotland by raiding and

desolating the Lowland districts. These English raids were usually

preceded or accompanied by a naval force, which sometimes sailed up the

Forth, destroying the shipping and harassing the towns round the coast.

One of these naval raids now brings Leith into notice. On the first Sunday

of May 1521 seven English warships made their way up the Firth, and

attacked the Port when the people were about to set out for morning

church. They bombarded the town, doing little harm, for they were on a lee

and sandy shore and feared to venture too near, but thought that

"such another peal to matins and to mass had not been rung in Leith

these twenty years." Off Inchkeith, where they replenished their

empty water barrels, they learned from a captain whose ship they had captured that no vessels were then

in the Port, save a barque of Davy Falconer’s and a ship belonging to

Hob a Barton. The others were all at sea, which was just as well perhaps

for the English commander, for when Davy Falconer and young John Barton

joined ships they could give the English long odds and win in the end.

Thus with the turmoil within the realm from feudal

strife and English raids, and wars upon the sea, the shipping of Leith

declined and trade decayed. An unemployment "dole" had to be

paid to the clerk who gave the bailie’s "tikket" allowing

ships to set out on their voyage, and another was paid to the keeper of

the Over Tron at the Bowhead, where all goods imported into Leith were

weighed, for overseas trade had almost ceased. Save the Unicorn, we

hear of no more ships being built. The dockyards of the Port and Newhaven

became neglected, and finally fell into decay and ruin. Leith again had to

revert to her former custom of purchasing what ships she required from

Holland, and not till the beginning of the eighteenth century did the

building of the larger ships again become an industry in the town. Much of

her trade, as in older days, again fell into the hands of Dutch and

Flemish shipowners, whose freights were lower even than those of her own

shipmen.

In 1527 continental politics took a change.

Henry VIII. was now in league with France against the Emperor Charles V.,

and Scotland, as her ally, was included in the Peace. But war, both by

land and sea, soon broke out again, and on the sea Leith was seldom out of

the fray. Early in the following year five armed ships, with the king’s

knowledge we are told, set forth from Leith Haven. The

capital

"H" shows that Newhaven is meant. It was

there that the largest vessels usually lay at this time.

The names of the ships are

not given, but those of some of the captains are, at whose sole expense

they were equipped. There were Will Clapperton, who lived on the Shore;

John Barton, who had all the fighting spirit of his more famous uncles,

Andrew and Robert; and John Ker, who was married to Barton’s sister

Agnes, and lived benorth the brig—that is, in North Leith. Evidently

they had some score to settle with the "auld enemy," and they

paid it with interest. For three months later they returned to Leith in

triumph with fifteen English prizes to recoup them for their outlay.

"Our Lord send amends of the false Scots," wrote the exasperated

English spy who had the unpleasant duty of sending this highly displeasing

news of the exploits of John Barton and his friends to his English

employers.

Certainly this English spy

had good cause to feel sore, for a similar capture of English ships had

been made the year before. "I would like to do the Scots some

displeasure," wrote the English Admiral of the Narrow Seas to Wolsey,

"for their cracks and high words." He was thinking of the Leith

sailormen when he wrote, for some proud words of John Barton had just been

reported to him by an English sea captain whom that bold Leith mariner had

relieved of both ship and cargo the day before, within the very seas

patrolled by the irate admiral’s ships. It almost seems as if Leith had

no need of shipbuilding yards in those stirring times.

Peace was at length

proclaimed, and Henry, having sent his nephew James the Order of the

Garter as a token of his goodwill, the latter thought he might safely

leave his kingdom for a time and venture overseas to France, where he was

engaged by treaty to marry a French princess. It was not considered

courtly etiquette for a king to go a-wooing in this way. James, no doubt,

inherited this impulsive side of his nature from his Tudor mother, who,

like her imperious brother Henry VIII., was constantly giving shocks to

her more sedately-minded subjects. Yet, as Leithers, we are pleased that

King James was no stickler for courtly convention, for his voyage in

search of a wife with a rich "tocher" to replenish his empty

treasury forms a pleasant and romantic episode in the almost unvarying

story of piracy and war that seems to form the staple of Leith’s history

during this period.

James did not set sail from

Leith as is so often stated, but the small fleet of seven ships did which

was to carry him and his brilliant retinue to France. The names of two

only of these ships are given—the Mary Willoughby, one of John

Barton’s captures from the English and the largest ship then belonging

to the Port, and the Morisat, whose name suggests that she was one

of the many captures by the Bartons from the Portingals. The fleet picked

up the king and his suite at Pittenweem, for they had all travelled

thither from his favourite seat of Falkland. In addition to their crews

the vessels carried five hundred soldiers, so that, in the event of attack

from English or other ships, the king might have a sufficient force with

which to oppose them.

In those days books were

few, and James, unlike his father, took no pleasure in them. Raleigh had

not yet introduced tobacco, indeed was not yet born, so, to relieve the

monotony of the voyage, whose length might vary from a few days to as many

weeks or even months, according to the wind, James took with him for his

own use two and a half barrels of sweetmeats and

a box of caramels. The storm-tossed fleet eventually reached Dieppe, to

the great alarm of the inhabitants of that quaint old port, for they took

the Scottish ships for some vengeful English squadron, until the red lion

of Scotland pierced with the French fleurs-de-lis, which seafaring Dieppe

knew so well, was seen at their masthead, when "thai war werie

rejoyssit of his coming."

The lady chosen for him not coming

up to James’s expectations, he fell in love with the beautiful

Madeleine, daughter of the French king, and she with him. The royal lovers

were married with all pomp and ceremony at Notre Dame, in Paris, in 1537.

James and his beautiful but delicate bride set sail from Dieppe with a

fleet of fourteen Scottish ships convoyed by eight French men-of-war, but

not before the English shore had been well reconnoitred to see if any

English ships were ready to dispute their passage, for this French match

must have been a sore trial to Henry VIII. At last, after a somewhat

stormy voyage, the fleet made the sheltered waters of the Forth, and came

to anchor off the harbour mouth at ten o’clock on Whitsunday evening.

Next morning Leith was all astir. In

the long twilight of the previous evening the townsfolk had watched the

fleet as it made its way up the Firth, and all had recognized the Mary

Willoughby as she proudly led the way, her tops and yards alive with

banners and streamers from mast to sea. When the queen stepped ashore she

knelt down in the fullness of her loving heart, and kissed "the

Scottis eard, and thanked God that her husband and she were cum saif

through the seas," little dreaming as she did so that ere six weeks

were to pass she would be laid to rest in Holyrood Abbey beneath the same

kindly Scottish earth.

Expectant crowds lined the

way as the king and his young and happy

bride, followed by a brilliant train of lords and ladies, rode along the

Shore under a veritable canopy of streamers from the ships lining the quay

wall. The hearts of all, men, women, and children, were at once captivated

by the charm and sweetness of the fair and gentle Madeleine. But soon all

this joy was changed to sorrow, for the excitement of her arrival and the

sudden change from the genial and sunny climate of France to the cold east

winds and chilly haars for which Leith and Edinburgh in May and June are

notorious were too much for this fragile lily of France. To the

inexpressible grief of the whole nation the loving and affectionate

Madeleine died in the midst of her happiness a few weeks after her arrival

on the Shore of Leith.

James was not a widower long, for in

the following year he married Mary of Guise, whom he had much admired

while in France the year before. Like Queen Madeleine, Mary of Guise

voyaged to Scotland in John Barton’s ship, the Mary Willoughby, but,

as Leith was threatened with plague, she landed near Crail, where James

met her. The marriage took place next day in St. Andrews Cathedral. Though

Mary of Guise did not land at Leith she was destined ere long to form very

close associations with the town, where memorials of her are still to be

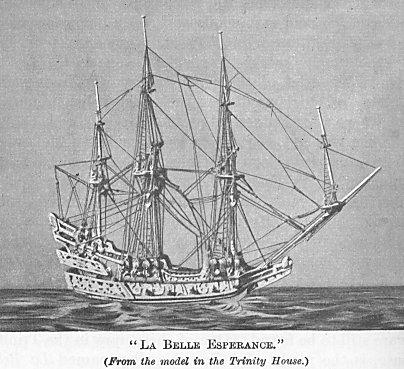

found. One of these, now in the Trinity House, is the model of a French

galley named La Belle Esperance, in which she is said to have

sailed to Scotland. Three galleons of France accompanied her on that

occasion, but only one, the Riall, which had also convoyed Queen

Madeleine, is named.

The marriage of James V. with Mary

of Guise was to prove a turning point in the history of Scotland and to

bring much woe to Leith. James, encouraged by his French wife, turned more

and more to France, while a

powerful section of the nobles, whose ranks were honey combed with

treachery, favoured closer relations with England. The result of these

diverging policies was the shameful rout of Solway Moss, the death of

James, and the poor defence against England in her savage wars against

Scotland during the early years of Mary Queen of Scots, when Leith more

than once was most cruelly ravaged by the "auld enemy." Peace

followed on the death of James, and a marriage was arranged between Henry’s

son, Edward, and the infant Queen of Scots, but the mischievous

interference of Henry spoiled all.

In his customary

high-handed way in dealing with Scotland Henry ordered the seizure of

several ships belonging to Leith and Edinburgh merchants and ship-owners.

They were on their way to France laden with fish, and relying on the

protection afforded by the peace had entered English ports under stress of

weather. Negotiations were begun with a view to having the ships and their

cargoes restored, but the English conditions were such that the patriotic

Edinburgh and Leith ship-owners and merchants boldly declared they would

rather lose their ships than become traitors to their country by agreeing

to them. The Scots thereupon repudiated the marriage treaty, and began to

establish closer relations with France.

Henry VIII. was furious at

what he called the "untrue dealing" of the Scots, and reverted

to the policy of "frightfulness" to bend them to his will. He

had gathered together a great fleet of ships for service against France.

He now ordered the veteran Earl of Hertford to employ these vessels in

conveying an expedition to Scotland by sea, so as to avoid any chance of

being intercepted and opposed on the Border.

Hertford’s instructions

were to burn Edinburgh, and so deface it as to leave a memory for ever of

the vengeance of God upon it; to sack Holyrood; to sack, burn, and destroy

Leith, and all the towns and villages round Edinburgh, "putting man,

woman, and child to the sword without exception where any resistance is

made." Such were Henry’s savage and barbarous instructions, and in

Hertford and his men, to whom mercy was unknown, he had fitting

instruments for carrying them out.

|