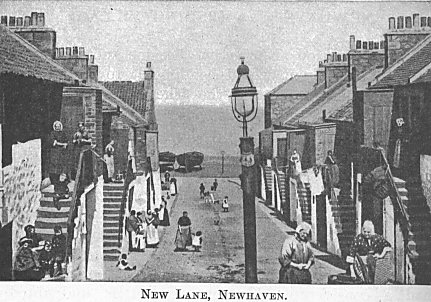

At what period Newhaven

became noted for its fisher population it would be difficult to say. A

persistent tradition tells that the fisherfolk came from the Netherlands.

We have already seen that a goodly number of the gunners and shipwrights

introduced by James TV. in the earliest days of Newhaven’s history came

from both the Netherlands and the northern shores of France, especially

from Normandy and Brittany. Hans, the king’s master gunner, was a

Fleming, while Jacques Terrell, who as James’s master wright played so

great a part in the building of his navy, was a Frenchman. That the

original population of Newhaven had a considerable Flemish element is

undoubtedly true, but the tradition that its fisherfolk are the

descendants of Flemish refugees, who settled here during the

life-and-death struggle of their nation against the might of Spain, we may

at once set aside as mere legend.

Fish has always formed a

large part of the food of the people of our district, and, down to the

early days of the nineteenth century, was almost the only meat the poorer

classes could afford. Newhaven was in early days, and still is, the chief

source of this supply. For centuries then, before the days of railways,

the fishwives of Newhaven travelled to their

Edinburgh customers by Whiting Loan (now Newhaven Road), through Broughton

village (for Pilrig Street and Leith Walk are modern) and up Leith Wynd,

where, after paying the petty customs on their fish, "new drawn frae

the Forth," they entered the High Street by the Netherbow Port. For

safety they always travelled in company in these law-less days, beguiling

the long and toilsome journey by singing in chorus the songs their

grandmothers had sung before them.

Accustomed to an outdoor

life from their early years and in all weathers, the fisherwomen are well

known for their strong and healthy figures. Yet even in our days of trains

and trams their strength must often be sorely taxed as they bear their

burden of fish up the steep streets, and still steeper stairs, for which

Edinburgh is notorious. A fishwife’s ordinary load varies from half a

hundredweight to a hundredweight, and, incredible as it may seem, heavier

loads are sometimes carried. A well-known song by James Ballantine, an

Edinburgh poet who might be called the children’s laureate, takes its

name and refrain from an incident that bears out what has been said about

the heavy loads the Newhaven fishwife is often accustomed to carry.

Ballantine happened to be passing when a fishwife was about to hoist on to

her back her heavily laden creel. He very gallantly went to her

assistance, and after doing so remarked with astonishment on the weight of

her burden. Her cheery reply as she adjusted the strap against her

forehead showed a happiness and contentment with her lot as unexpected as

was the beauty and poetry of the words in which it was expressed—"

Oo, ay, but ilka blade o’ grass keps its ain drap o’ dew."

But the Newhaven fishwife

has other praiseworthy characteristics besides a happy contentment with

her lot. As the creel becomes lighter, her industry and thrift are very

much in evidence on her journeys, for she usually knits whenever her hands

are free, and thus keeps herself and family well supplied with good warm

stockings. As they ply their trade with creel on back, the fishwives of

Newhaven are, from an historical point of view, the most picturesque

figures met with in our streets. Not only are they the last of our old

street traders, who formed such a prominent part of the street life in

days gone by (as it is mirrored for us in the poems of Dunbar, Fergusson,

and other Scottish poets, and in some of the novels of Sir Walter Scott),

but they ply their trade to-day in almost the same garb, and in pretty

much the same way, as they did centuries ago, when the Stuarts held court

in Holyrood.

The fishwives of Newhaven

are in our day the only old-world figures still to be seen in our streets,

and as such they form a link connecting us with the figures in the

bustling crowds that thronged the thoroughfares of Edinburgh and Leith in

far-off days. The dress of the fishwife is familiar to all. Henley, the

poet, has described it in his sonnet entitled "At Fisherrow,"

and Charles Reade has given it several paragraphs in Christie Johnstone,

his well-known novel on Newhaven fisher life of sixty years ago, named

after its heroine, a Newhaven fisher lass. Charles Reade spent some weeks

here in the autumn of 1852. His picture of Newhaven fisher-folk and their

ways is hardly a true representation, and, like most English novelists, he

is not very happy in his Scottish dialogue. The best thing in the book is

the portrait it draws of Dr. Fairbairn, so long Free Church minister here,

whose church Reade attended while residing in Newhaven. The great majority

of the congregation were fishermen and their families, who were always

keenly appreciative of the manner in which Dr. Fairbairn prayed for those

exposed to "peril on the sea."

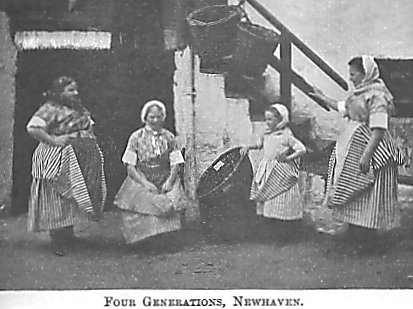

The Newhaven fishwife’s

dress is admirably adapted to her calling. Its most noticeable feature is

the multiplicity of short petticoats, the home-knitted stockings, usually

black, and the neat shoes. The numerous petticoats are a necessity of her

vocation. Secured round her waist by broad bands, the bulging flannel

forms a saddle for the creel, without which it would be equally difficult

to balance and to carry, while their numerous folds form a protection both

against wet weather and the drip of the creel.

To the lay mind all

fishwives seem dressed alike, but there are several marked differences

that distinguish those of Newhaven from those, say, of Fisherrow. The

Fisberrow fishwife has a greater length of skirt and her creel band is

always of leather, while that of her Newhaven sister is usually of canvas,

which is well scrubbed every week to match her usual trig appearance. The

girls generally go bareheaded, and the married women often follow their

example and have no other head-dress than their own abundant hair brushed

close and smooth.

Frequently, however, the

married women wear a frilled cap that seems to indicate that old

connection with the fisherfolk of Flanders, Normandy, and the coasts of

Brittany.

Such are the fishwives of

whom, when driving through Newhaven in 1872, the late Queen Victoria saw

"many very enthusiastic, but not in their smartest dress." In

their smartest dress the Newhaven fisher girls are undoubtedly the golden

butterflies of their kind. As such they have been invited to concerts in

many large English towns, and a dozen of them were sent as attendants to

the great London Fisheries Exhibition of 1883, when they were hospitably

entertained by Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle, and by the Prince and

Princess of Wales (afterwards King Edward VII. and Queen Alexandra) at

Marlborough House. As a result of this visit the fisher girls’ garb as a

costume for ladies became fashionable all over the country, silks and

finer cloths being substituted for the more common and more durable

material. As we notice the brightness and colour added to our street

scenes by the fisher girls of Newhaven when in gala dress we cannot but

regret that so few of the old-time national costumes survive among us

to-day.

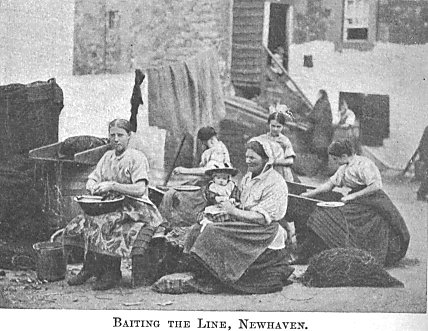

Until recent years the

inhabitants of Newhaven rarely married outside their own community. Their

marriages have been aptly described as a union of talents as well as of

hearts. A woman of any other class would be almost useless as a fisherman’s

wife, unacquainted as she would be with the baiting and the preparation of

lines and the mending of nets, and unable to assist him in the maintenance

of the family by donning the creel and disposing of his catch. Sir Walter

Scott, who knew the Newhaven people and their sayings well, is referring

to this in The Antiquary when he makes Steenie’s mother, Maggie

Mucklebackit, say to his sweetheart Jenny, "You’ll no dae for

Steenie, lass; a feckless thing like you’s no fit to mainteen a

man." The Newhaven fishwife is indeed the head of the household,

ruling her husband along with the. other members of the family, and

believing with Maggie Mucklebackit that "Them that sell the goods

guide the purse; them that guide the purse rule the house." And how

well she guides the purse is borne out by the fact that Newhaven is

reckoned to have the wealthiest fishing community on the Forth, many of

the houses being owned by their thrifty occupants.

A wedding in Newhaven,

until some thirty or more years ago, used to be a very notable event, and

as most of the inhabitants were more or less known to each other, if not

related, it was generally attended by a large number of the younger

members of the community. The bride in her braws, accompanied by her

sweetheart, went round some time before and invited the guests personally.

On the wedding day they walked in couples from the bride’s house to the

"Peacock," the "Marine," or other hotel, where the

marriage was to be celebrated.

"And a’ the boats wi’

flags were decked,

Frae Annfield to the pier;

And Doctor Johnstone, worthy man,

Had twa three hours to spare,

Sae he toddled to Newhaven,

And spliced the happy pair."

As

many as one hundred couples have "walked" at a Newhaven wedding,

the male guests frequently, as in the old-time "penny weddings,"

paying their own and their partner’s share of the wedding supper. Such

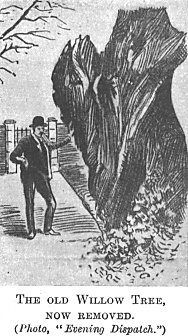

wed. dings, like other old fisher customs, have gradually gone out of

fashion, as the younger generation are no longer following the vocation of

their parents, and the prophecy of the old spaewife anent the great willow

tree that once grew and flourished at Willow Bank so many long years ago,

As

many as one hundred couples have "walked" at a Newhaven wedding,

the male guests frequently, as in the old-time "penny weddings,"

paying their own and their partner’s share of the wedding supper. Such

wed. dings, like other old fisher customs, have gradually gone out of

fashion, as the younger generation are no longer following the vocation of

their parents, and the prophecy of the old spaewife anent the great willow

tree that once grew and flourished at Willow Bank so many long years ago,

"When that tree shall

decay,

The open sea-boat fishing trade shall also die away,"

seems fast coming true.

The young men are now

either joining the trawlers or entering some trade, while the majority of

the Newhaven girls will no longer carry the creel, and, discarding the

picturesque fishing costume, follow other walks in life, many of them

being employed in Messrs. Devlin’s net factory at Granton and other

public works in the neighbourhood. Though such a sight was common a

generation ago, it is only on rare occasions now that one sees fisherwomen

baiting and preparing lines at their doorstep in Newhaven. The day of the

small trader in the fishing industry, as in most others, is over, and thus

the old-time fishing boats, with their tall, straight masts and brown

sails, than which nothing could be more picturesque, are not so numerous

in Newhaven harbour as they once were. The trawler has almost driven the

line fisher from the fishing grounds, just as the fish shop, and more

especially the fish cart, even in Newhaven itself, is driving the fishwife

out of the market. The cry of "Caller herrin’" is seldom heard

in our streets, and soon will be remembered only in the touching words of

Lady Nairne’s fine song, whose beautiful air was composed by Nathaniel

Gow from a blending of the music of St. Andrew’s church bells with the

notes of a fishwife’s cry, as she hawked her fish along George Street

when that fine thoroughfare was a residential and not a business quarter

as it is to-day.

From the gay and romantic

times of James IV. down to the boyhood days of our grandfathers many

fisherwomen earned their livelihood by the sale of shellfish. The cries of

"Cockles and mussels," "Wulks and buckies" are no

longer heard. The vendors of these, however, now reduced to some

half-dozen fisherwomen and girls, still remain, and form an interesting

picture of Old Edinburgh street life. They are all, with the exception of

one, who has her stance in Leith Street, to be found in the Old Town—in

the High Street, Bristo, and St. Mary Street, and near the very spots

occupied by their predecessors of four hundred years ago. These fisherfolk

are usually to be found on Saturdays only, and all come from Fisherrow. No

Newhaven fishwife would now condescend to sell shellfish on the street,

for by her it is no longer considered a fish trade of the first class.

In the evenings during the

months of May, June, and July the Newhaven fisher girl, with creel on back

and rather more trig in her get-up than usual, though not in her smartest

dress, may be found at some busy centre such as the Theatre Royal or the

foot of Leith Walk. Here towards sunset the cry of "Caller partans"

may fall pleasantly on the ear. It is usually rendered "Caller parte-e-e,"

for the fisher lass seems to take pleasure in prolonging the last syllable

to make her cry more effective, and to save herself its too frequent

repetition.

The season of partans used

to be followed by that of oysters.

"September’s merry

month is near

That brings in Neptune’s caller cheer,

New oysters fresh;

The halesomest and nicest gear

O’ fish or flesh."

During every month with the

letter "r" in it—that is, from September to April—the cry of

"Caller ou" (that is, Caller oysters), the most beautiful of all

the fisherwomen’s cries, was frequently heard on the streets after

"the aucht hours’ bell." Evening oyster parties were

fashionable in old-time Edinburgh and Leith, and many a "snell

repartee" used to be exchanged between the oyster lass and her

customers. The supply of oysters in the Forth, from overdredging and other

causes, is now extremely limited.

Oyster dredging employed

the local fishermen from the close of the summer herring fishing off the

north-east coast until the opening of the winter herring fishing in the

Forth, and the sale of oysters was a lucrative source of income to the

fisherwomen. The Forth oyster beds are slowly recovering themselves, and

the time may again come when the melodious cry of "Caller ow-ooh,"

as it was pronounced, which even yet is occasionally heard on autumn

evenings in our West End squares, will once more become familiar to our

ears, and the picturesque form of the Newhaven fisher girl, as in days

gone by, be more frequently seen in our streets.

An important institution of Newhaven that

was wont to bring itself more frequently into public notice than it does

now is the Free Fishermen’s Society, which is said to date from 1572.

The annual election of the boxmaster of this society, Until a very few

years ago, gave Newhaven its annual gala night, when a great torchlight

procession was formed for the "lifting of the box" and its

conveyance to the house of the new boxmaster for the year. This event was

followed by a supper noted for its flowing bowl. In more temperate days

this supper became a soiree, when the Rev. Dr. Kilpatrick usually occupied

the chair, and on these occasions was generally in his best story-telling

form. The soiree, like the supper, is now among the things that were. The

Society, for the nominal rent of ten shillings per annum, has perpetual

lease from the Government of the Free Fishermen’s Park, which is all

that remains of the once extensive Newhaven Links.

We have now followed the outline of

Newhaven’s history from its earliest days to our own times. At first it

seemed destined to become a great shipbuilding port, but the untoward

death of James IV. on Flodden Edge ended those hopes, and it gradually

declined into the little fishing village it remained down to the Close of

the eighteenth century. After the Turnpike Road Act of 1751, which did so

much for Scotland’s progress, and the consequent great development of

the stage coach, Newhaven became the busiest and most important ferry and

packet station in Scotland; but its somewhat primitive pier and breakwater

could not possibly hold out against the magnificent docks and piers which

in 1848 drew the railway to Granton, and it sank once more into a fishing

village as we know it to-day.

Once again, however, the

stir and bustle of trade have invaded it, and, as a fishing village, it

now seems about to regain the fame it has lost as a port. Yet, strange as

it may seem, it is as the little fishing village that Newhaven has

achieved its greatest distinction, for, by sending its musical cries of

"Caller herrin’" and "Caller ou" sounding over the

globe, it has become known to fame wherever the English language is spoken

and Scots songs are loved.