WHILE we know the names of a large number of Scottish

ships belonging to James IV.’s time, we cannot always distinguish the

vessels of the king from those of other owners. A recent great writer of

Scottish history, however, estimates that the navy of James at its best

consisted of sixteen large ships and ten small ones. Such a large fleet of

royal vessels shows us that, even although the king sometimes purchased

ships from abroad, his own dockyards at home must also have been unusually

busy.

The Margaret was perhaps the largest Scottish

vessel then afloat; but James was ambitious to possess ships still larger.

From the difficulties encountered by the ingenious Jacques Terrell, James’s

master wright and chief naval designer, in floating the Margaret over

the entrance of her dockyard at the Shore it was evident there was not

sufficient depth of water to permit of the construction of larger vessels

at Leith. But by men like James IV., Sir Andrew Wood, and the Bartons,

this difficulty was soon overcome. Little more than a mile farther west

the depth of water at high tides was much greater than at Leith, and there

the king resolved to construct new dockyards for the building of larger

ships, while he still retained those at Leith for constructing vessels of

normal size. This resolution had no sooner been arrived at than work was

begun, and even before the Margaret was ready for sea the Novus

Portus de Leith—that is, the New Haven or Harbour of Leith, and now so

well known as the fishing village of Newhaven—was in process of

formation.

The land on the west side of the Water of Leith,

however, did not belong to the king. It was the property of the abbot and

canons of Holyrood, and would require to be purchased from them before any

new harbour could be constructed there; but the royal ships and shipyards

had already cost so much that Sir Robert Barton, the clever keeper of the

king’s purse, had little money wherewith to indulge in any new

expenditure. But difficulties only appeared to be at once overcome; for

the king gave the abbot and canons a portion of his rich lands in and

around Linlithgow for some acres of the grassy lands so long known as the

Links of North Leith, of which all that remains to-day is the Free

Fishermen’s Park adjacent to the Whale Brae.

In 1504 trees to the number of one hundred and

sixty-three were purchased from the Laird of Inverleith for the

construction of the new village. The labourers employed in this work were

lodged in a great pavilion brought from Edinburgh Castle and erected on

the grassy links until houses were built. But housing was pushed on

rapidly, and Newhaven became ere long quite a large village and the seat

of a considerable population, of whom many were French, some Flemings, and

others Dutch. Mingled with these were a few Spaniards, Panes, and

Portuguese.

As James, like his mother before him, was devoted to

the Church, he early made provision for the spiritual welfare of his many

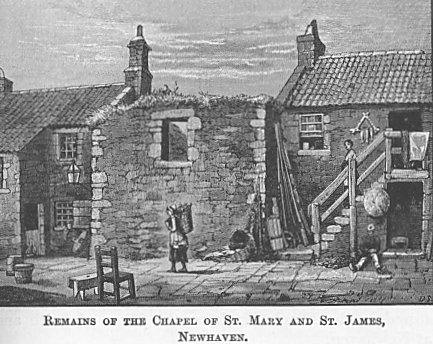

shipwrights and other workmen at Newhaven. We find that the building of a

chapel dedicated to the Virgin and St. James was going on in 1505, and in

little more than a year afterwards we see it open for service and the king

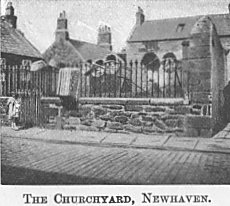

presenting it with a silver chalice or communion cup. The only remains of

this chapel to be found in Newhaven to-day are the west gable of the nave

which stands on the right as you go down the Westmost Close, and its

little God’s-Acre which forms a green enclosure adjacent in Main Street.

Our ancestors in these old times had a happy gift of putting much poetry

into their place-names, and so, from the fact of their chapel being

dedicated to the Virgin, Newhaven was commonly known by the highly poetic

name of Our Lady’s Port of Grace.

As the building of a fleet was an undertaking very dear

to James’s heart, we soon find him showing the greatest interest in the

construction of the New Haven by frequent visits to the works from his

royal palaces at Holyrood and Linlithgow, and by encouraging the workmen

with gifts of the inevitable "drink-silver," as in 1504, when he

sent fourteen shillings by the hand of Sir Robert Barton to "the

marinaris that settis up the bulwerk of the New Haven." Three years

later, in 1507, the works were still being extended, for in that year we

find another bulwark erected and a new dock being excavated.

No

sooner was the first dock ready than shipbuilding began, and preparations

were made for the construction of a warship superior to any yet afloat. We

find timber and other material for the "great schip," afterwards

known to fame as the Great Michael, being brought from many

quarters and stored in the King’s Wark on the Shore of Leith and at

Newhaven.

No

sooner was the first dock ready than shipbuilding began, and preparations

were made for the construction of a warship superior to any yet afloat. We

find timber and other material for the "great schip," afterwards

known to fame as the Great Michael, being brought from many

quarters and stored in the King’s Wark on the Shore of Leith and at

Newhaven.

This great ship seems to have been laid on the stocks

about 1507, and her construction was carried out under the superintendence

of Sir Andrew Wood, perhaps the greatest of James’s many sea captains.

In a poem addressed to the king himself by William Dunbar, the famous

Scots poet of that time, we have a brief but graphic word-picture of the

stir and bustle that reigned in the naval yards of Leith and Newhaven at

this period—a word-picture undoubtedly suggested by what he had so often

seen at these places with his own eyes. In this poem Dunbar talks of the

"Carpenters,

Builders of barks and ballingars,

Masons lying upon the land,

And shipwrights hewing upon the strand."

To Lindsay of Pitscottie, in Fife, perhaps the most

picturesque and attractive writer of Scots history, we owe much

interesting information about the building of the Great Michael. Although

doubt has been thrown on many of the details of his graphic narrative, yet

we must remember that Pitscottie was near neighbour to the Woods of Largo,

and is therefore likely to have had authentic information about Sir Andrew

and the great ship of which he was commander. Pitscottie, after the manner

of the old balladists, tells us that the Great Michael was "a

year and a day" in building; but that is only his picturesque Scots

way of saying that she took a long time to build, and we know from other

sources that she must have been on the stocks for four years at least.

During this long period James took the deepest interest

in every detail of her construction, and was therefore a frequent visitor

to Newhaven, where his kindly consideration and attractive manner, as in

Leith, Soon won for him the devoted and affectionate loyalty of the whole

population. No accident to any of the workmen and no case of sickness

among the villagers ever failed to call forth his kindly sympathy and

ready help. We find him giving fourteen shillings to "ane pure wyff

becaus hir husband brak his leg at the king’s werk and had nathing to

amend it with." One of his French shipwrights died and was buried in

the little churchyard of St. Mary’s Chapel. The king not only paid all

the expenses of the illness and burial, but also sent the widow back to

her native Rouen to which she longed to return. Even the poor charwoman

who kept the court that led to the works is not forgotten when she

"is fallen seik." The king’s courteous and kindly bearing

encouraged even the humblest of his subjects to approach him with freedom.

There must have been fishermen in Newhaven even in

those early days of its history, for we find James going with them to the

oyster-dredging. As the fishers were accustomed to sing songs while at

work, and the king was passionately fond of music, we may be sure the

"dreg song" was struck up on these occasions, for

"The oysters are a gentle kin’,

They winna tak unless ye sing."

In 1506, a year when summer days were more than usually

fine, a Newhaven woman brought the king the first strawberries of the

season, a fruit for which James had a particular fondness, while on

another occasion he received a gift of plums "at the bridge end of

the New Haven." Again we see him later in the same season purchasing

"hony peris" from a fruitseller at the pier end. A pleasant

place evidently was this Newhaven of long ago, with its cottages set in

shady gardens, gay with blossom in the pleasant springtime, and rich with

fruit in mellow autumn, the honey pears and the plums in all likelihood

from trees grown from slips brought by James’s French shipwrights from

the sunnier and warmer shores of Normandy and Brittany.

Sometimes King James rode down from Holyrood in the

early morning on his favourite steed Grey Gretno, when the exercise and

fresh morning air put rather a keen edge on his appetite. On such

occasions, there being no inn at this time in Newhaven, he "disjonit"

(French déjeuner—to breakfast) at the house of one of his French

shipwrights, whose wife was seemingly known to local fame as a cook

skilled beyond her neighbours. Royal visits were everyday incidents in

Newhaven in those distant days.

Perhaps the most pleasing Newhaven memories associated

with those of James IV. are connected with the nameless little Newhaven

girl to whose identity we have no clue whatever, for the king never speaks

of her except as "the little lass." Children, unless they are of

royal blood, do not figure largely in State documents, and are not often

met with in local history. King James, however, always seemed to be

specially interested in them; it might be because he had lost so many of

his own, "which grevit him sae sair that he tvald not be

comforted." He possessed in a very high degree all that charm of

manner so characteristic of the Stuarts, which drew to him both young and

old. At Newhaven we see James’s love for children shown in his interest

in this little nameless lass, whose charm and grace of manner seem to have

been no less attractive than his own, and whose little heart he was wont

to make glad on his visits to his dockyards with the small money gift of a

groat, perhaps to buy strawberries from one of those sunny gardens where

they used to ripen so early, or, if autumn were the season, to purchase

honey pears from the fruitseller at the pier end. What an interesting

story of child life in the days when James IV. was king might be written

round the title, "The Little Lass in Newhaven."

During the years 1508-11 we know little of what went on

in Newhaven, as the king’s accounts for those years have not come down

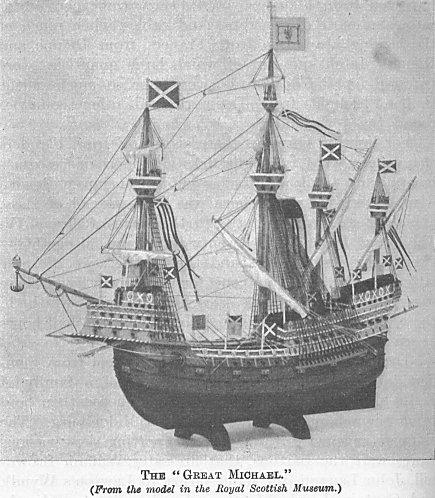

to us. The Great Michael, by far the largest ship built in Europe

in those days, was still on the stocks. The best account we have of this

great ship is from the pen of that picturesque old chronicler, Pitscottie,

whose word-pictures are so often credited with owing much to the free play

of his imagination.

According to Pitscottie, the Great Michael wasted

all the woods of Fife except those of Falkland in addition to all the

timber that was brought from Norway. Here Pitscottie must have put a great

restraint upon his powers of story-telling, for when we examine the

account books we find that he has understated, rather than exaggerated,

the amount of timber used in her construction. Not only were supplies of

timber sought in all parts of Scotland, but they were also largely

imported from the Continent, and especially from France and the Baltic or

"Estland Seys."

The dimensions of the Great Michael, as given by

the same chronicler, were two hundred and forty feet long, thirty-five

feet broad, with sides of oak ten feet thick. With such dimensions as

these, it is not surprising that she wasted all the woods of Fife, and

required in addition many cargoes of timber from Norway and other lands

beyond the sea.

Besides the timber, much of the other material employed

in the construction of this great ship also came from the Continent, and

chiefly, of course, from those countries with which Leith was accustomed

to trade most, such as the Low Countries, France, Scandinavia, Denmark,

and Poland. We see the enmity between England and Scotland that did so

much to hinder their mutual trade in olden times in the fact that tin and

copper from Cornwall were got via Antwerp.

The guns came mostly from Flanders, though many were

made in Edinburgh Castle and stored in the King’s Wark on the Shore.

Hundreds of "gun-stanes "—the general name for cannon balls at

this time—were also imported from Flanders. With them came canvas for

sails, and most of the ropes and cables, while much of the rigging also

came from France—from Dieppe and Rouen. Pitch and tar, of which large

quantities were required for the dockyards, were, like so much of the

timber, brought from Denmark and other countries round the "Estland

Seys."

For lighting purposes there also came from Flanders

chandeliers—that is, candlesticks of a more or less ornamental kind—and

horn for bowets to the ships. Bowets were lanterns in which horn was used

instead of glass, a highly expensive material in the reign of James IV.

The Great Michael had twenty-six bowets altogether - twenty-three

small ones and three large, two of these latter for the stern and one for

her bow. Then there were the "night-glasses," or sand-glasses,

which in those clockless days were used to indicate the hall-hours at sea

as is still done by bells.

The compasses for the ship were also got from Flanders,

and George Paterson, a member of a family of Leith mariners, was

commissioned to choose them and bring them home with his ship from

Middelburg. The skippers engaged in the work of importing these various

stores were the Bartons, that fire-eater William Brownhill, John Lawson

(the name-father to Lawson’s Wynd), and Captain Lamb, of whose family we

have already heard and of which we shall hear still more.

The Great Michael seems to have been

launched in October 1511, but the event is nowhere definitely stated. So

notable an incident, however, could not fail to be celebrated as a gala

day in Newhaven, and so we find payments being made to Scottish trumpeters

"at the outputting of the kingis gret schip." James would be

there and so would Queen Margaret, and with them a brilliant train of

lords and ladies from Holyrood. Congratulations on the success of the day’s

event would be showered from all sides on Sir Andrew Wood and Jacques

Terrell, the master wright, who in those days was designer as well as

builder.

When finally out of the builders’ hands and furnished

with her full equipment, she made a brave show as she rode at anchor some

two miles from the shore, with her richly carved and decorated forecastle,

her huge poop, her four great masts alive with banners and streamers, and

her sails, as was the custom of the age, emblazoned with the royal and

other coats-of-arms.

But even then she gave her commander, Sir Andrew Wood,

and Jacques Terrell, the master wright, no end of trouble, for owing to

her huge size and cumbersome build she was somewhat difficult to navigate.

For this reason she had the misfortune to run aground in one of her early

trips in the Firth, which had not then its shoals and shallows indicated

by buoys as it has to-day. The result was that there were added to her

crew three pilots, who, strangely enough, were all Frenchmen, and whose

duty it was to mark out the deeper channels.

Now that the Great Michael was making such an

imposing show as she lay at anchor in the Roads, and had no further need

of his services aboard her in the meantime, Jacques Terrell sailed for

France in February 1513 with the French ambassador, De la Motte. The

master wright went to France to enlist fourscore French mariners, perhaps

to act as gunners, for the Great Michael. He sailed from Newhaven

in De la Motte’s little bark called the Gabriel. As Will

Brownhill, with three ships under his command, left Leith at the same

time, ostensibly for Flanders to deceive the English spies, but really for

France, he almost certainly joined De in Motte as convoy to his ship, the

little Gabriel, which was freighted with wool fleeces and salted

hides, two of Leith’s staple articles of export.

Ambassadors in those days seemingly joined trade with

diplomacy, and did not disdain to combine a little piracy with both when a

successful opportunity came along. Like her more famous namesake in the

old English ballad, the Gabriel sailed away adventurously to meet

whatever fortune, chance, or Providence might send. Off Flamborough Head

she fell in with an English ship making for Newcastle with a cargo of

wine, which was promptly captured and sent on to Leith with a prize crew.

Now such an exploit was not the unaided work of the

little Gabriel, and, as the prize was sent to Leith, we may

conclude that Will Brownhill and his three ships had not been far off. To

be sure Scotland and England chanced to be at peace at that particular

time, but that counted for little on the high seas, where a state of war

between the mariners of the two countries was the normal condition of

affairs.

At this time, according to the letters of the English

spies, James visited his ships at Newhaven daily, going early in the

morning and remaining until the dinner-hour, which was then at twelve o’clock.

How many ships had been built at Newhaven it is now impossible to say. In

the letters of the spies of Henry VIII. we read of ships in course of

building, but we have no clue to their names.

Just at this very time we have an account from the

English ambassador himself of his visit to Leith and Newhaven. He was as

much spy as envoy, which James, who perhaps suggested the visit, seemed to

guess. James had boasted that the Great Michael carried more guns

than the French king ever brought to the siege of a town. The English

ambassador wrote to King Henry that this was "a great crack," or

lie, but was too polite to say so to James. He, however, went down to

Leith to see the ships for himself, and then went on to Newhaven, but as

some of the largest of the king’s ships, unknown to this rather

sell-satisfied Englishman, were safely out of sight far beyond Queensferry,

he sent a rather disparaging report of the size of James’s navy to his

lord and master in the belief that he had seen the whole of it.

Jealous for their port of Leith, the burgesses of

Edinburgh, we are told, looked with no friendly eye upon the growing

importance of Newhaven, for much injury was done to the royal burghs and

their monopoly of the overseas trade by vessels sailing from such ports as

Newhaven, over which they had no jurisdiction. In 1510, therefore, they

purchased Newhaven from James, whose many expensive enterprises left him

in constant need of money.

The charter granted to the city by the king describes

Newhaven as "the new port called Newhaven, lately constructed by the

king on the seashore between the Chapel of St. Nicholas in the north part

of the town of Leith and the lands of Wardie." From this charter we

further learn that Newhaven had at this time at least one street, the

South Raw. While the burgesses of Edinburgh thus obtained complete control

of Newhaven, they were at the same time bound to uphold the pier and

bulwarks for receiving and protecting the ships and vessels sailing

thereto.

This grant of Newhaven to the city of Edinburgh in no

way interfered with its use as a place for the construction of the king’s

ships, but with the departure of James’s fleet for France in 1513, the

larger portion of which never returned, the great days of Newhaven as a

shipbuilding port came to an end. The death of James at Flodden, the

misrule and lawlessness which followed, and the failure of Edinburgh to

uphold the pier and bulwarks gradually led to its decline. No vestige of

the pier and once busy dockyards erected by James IV. survives in Newhaven

to-day.