|

ANOTHER noted family of

Leith sailormen, who for several generations were the most renowned

seafarers belonging to the Port, was that of the Bartons, one of whom,

Wood’s old friend, Sir Andrew Barton as he is so often called, although

there is no record of his ever having been knighted, was among the most

famous and daring sea-captains of his time. If Wood was the Scottish

"Nelson" of his day, Andrew Barton was undoubtedly the Scottish

"Drake."

The first of this family to

come into prominence was John, a noted mariner of Leith, who, in the reign

of James III., was skipper of the Yellow Carvel, described as one

of the king’s ships. Under his command the Yellow Carvel seems to

have met a good deal of ill-fortune, for she was captured by the English,

although afterwards restored by Edward IV., and was then nearly wrecked

among the rocks off North Berwick before she won fame under the captaincy

of the brave and skilful Sir Andrew Wood.

John Barton had three sons,

all of whom rose to fame — Andrew, the eldest and most renowned; Robert,

familiarly known among Leith sailor folk as Robin, and by the English, who

held him in wholesome dread, as Rob o’ Barton; and John, who was only

less celebrated than his two elder brothers. All

of them were distinguished naval officers of James IV., and skilled and

daring navigators. They fought in many a stubborn sea fight between Norway

and the Canaries. The names of all three brothers, and most frequently of

all that of Andrew, occur in Andrew Halyburton’s ledger, showing that

they traded more or less regularly between Leith and the Low Countries.

For nearly a hundred years the

Bartons carried on a kind of family war with the Portuguese. The quarrel

began in 1476. In that year John Barton, the first of that family to come

into fame, was voyaging from the port of Sluis, in Flanders, homeward

bound in the good ship Juliana, laden with a valuable cargo, when

he was attacked by two armed Portuguese vessels. After a stout resistance

the Juliana was captured, and the survivors among the crew were

thrust into a boat and cut adrift. Among them was their gallant skipper,

John Barton, who made his way to Lisbon to seek redress for the wrong that

had been done him, but in vain; nor were the efforts of James III. with

Alfonso V., King of Portugal, any more successful.

Letters of reprisal, or warrants,

were therefore granted by the Scottish king to the Barton family,

authorizing them to seize Portuguese vessels and cargoes until they had

made good their father’s losses, which were reckoned at 12,000 ducats,

or about £6,000—a great sum for those times. Andrew Barton seems to

have been the most active of the three brothers in capturing the richly

laden caravels of Portugal returning from India and Africa. The Portuguese

were not slow to retaliate, and for years a regular war on the high seas

ensued between the Bartons and other bold Leith mariners on the one hand,

and the Portuguese on the other. But such piratical attacks both

unauthorized and those authorized by letters of marque or reprisal, were

ordinary incidents of fifteenth-century navigation.

Among the captures of the Bartons

from the Portuguese that made a great sensation in Leith and Edinburgh

were two negro maids, who had no doubt been carried off from the coast of

Guinea to be sold as slaves. A much more kindly destiny, however, was in

store for them. The Bartons presented the "Moorish lasses," as

they were popularly called, to King James IV., who not only accepted the

gift but took the greatest interest in their welfare. A devoted son of the

Church, he had them baptized as Margaret and Ellen, perhaps after the

youthful Queen Margaret and the wife of the Governor of Edinburgh Castle,

where they were housed as maids to some of the Court ladies. Dunbar, the

great Scottish poet of that time, who knew the "Moorish lasses"

well, reflects their happy lot in his poem entitled "Ane

Black-Moor" :—

"Quhen she is claid in riche

apparel

She blinks as bright as ane tar barrel,

My ladye with the mekle lippis."

At this time a small fleet of

Scottish merchantmen sailing in company, as they so often did as a

precaution against pirates, was attacked by some Dutch ships. The Scottish

vessels were plundered, and their crews and the merchants who sailed with

them were thrown overboard, for merchants or theft factors usually

accompanied their wares oversea in those days when the post did not exist

and orders could not be made by letter. Andrew Barton, whose daring and

skill had early recommended him to the favour of King James, was

dispatched with ships to avenge this act of savagery. Barton

completely cleared the Scottish coasts of the Dutch ships, and sent to the

king a number of barrels full of the heads of the Dutch pirates as a token

of the thoroughness with which he had carried out his orders.

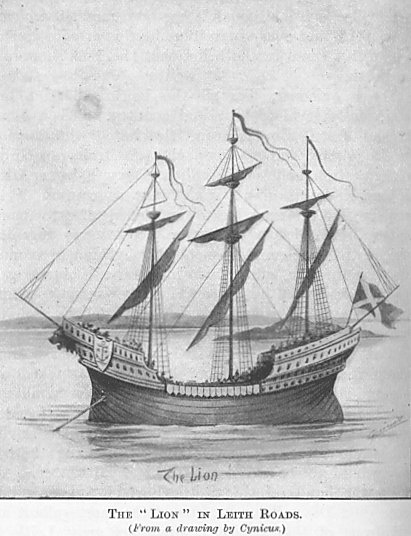

It was on account of these

attacks on the Portuguese that Robert Barton was arrested and his ship,

the Lion, seized by the magistrates of Campvere, in Holland, at the

instance of some Portuguese merchants who had been despoiled by the

Bartons. He was sentenced to be hung as a pirate if he did not make good

their losses; but Robin Barton was not to die so ingloriously. James IV.

wrote to Margaret of Savoy with all the confidence of one who had no doubt

as to the issue, explaining that the attacks against the Portuguese were

perfectly legitimate, as they had been done under letters of marque given

by himself; and the result was, as James had so confidently anticipated,

that Barton and his ship were set free.

This ship of Robert Barton’s

would seem to have been the same great war vessel aboard which his gallant

brother, Andrew Barton, fought his last fight in August 1511. If this be

so, then it shows us, what indeed we know from other sources, that, like

the rest of their ships, the Lion was a joint possession of the

Barton family and their friends. Joint-ownership of vessels was the method

adopted by shipowners in Leith and other Scottish ports to minimize their

losses from the manifold perils of the sea in mediaeval times, when marine

insurance, though common in Italy, the Netherlands, and even in England,

was unknown in Scotland. Whether this great ship of the Bartons was a

capture from the Portuguese which they renamed the Lion, or whether

they had bought her in France or the Netherlands, as was then customary,

since shipbuilding had not as yet arisen as an industry in the Port, we

have now no means of knowing.

On the capture of the Lion

by the Howards the Bartons immediately replaced her by another ship of

the same name equally large, for among the warships James IV. sent to help

France during the Flodden campaign was one named the Lion, under

the command of Robert Barton. After his death in 1538 the Lion became

the possession of his nephew John, the worthy successor in skill and

courage of his famous uncles. That this second Lion was in no way

behind her more noted predecessor in size and equipment we learn from the

all too brief notice of her untoward fate. "There is great maine

(grief) here," wrote an English spy from Edinburgh in March 1547,

"for a Scots ship of war, the Lion, wrecked near Dover with

eleven score men (that is, fighting men), besides mariners." We can

well believe, as a letter of James VI.’s to the Kirk Session of South

Leith Church tells us, that in those troublous days "poor widows and

orphans" of sailormen were always numerous in Leith.

Ever since the marriage of James III. with

the saintly Margaret of Denmark there had been a close alliance between

Scotland and that country which continued to the Union of the Crowns, and

led to much coming and going between Copenhagen and Leith. In 1508 Andrew

Barton was sent with ships to assist Denmark in her struggle with the

powerful city of Lübeck, the head of the Hanseatie League. But the career

of Andrew Barton soon after this came to an end. He had been cruising on

the look-out for the richly laden ships of Portugal as they returned from

the Indies and the Guinea coast. This capture of Portuguese merchant-men

inflicted serious damage on the commerce of London, and the merchants of

that city raised a clamour against the interference with their trade.

Henry VIII. had sent no complaint against

the brilliant Leith sailorman to the Scottish king.

Evidently he had none to send, for Henry was never

slow to air and make the most of a grievance when he had one. Indeed there

does not seem to be any act of unlicensed piracy recorded against the

Bartons. But that mattered little to the English, who, jealous that

Scottish seamen should match, if not even outrival, their mariners on the

sea, determined to effect Barton’s capture. At the earnest request of

Sir Thomas and Sir Edward Howard, the latter of whom afterwards perished

in such another fight against the French, Henry allowed them to fit out an

expedition against Barton, who had with him his great ship, the Lion, and

her pinnace, the Jenny Pirwin.

The Howards were piloted by the skipper of

a merchant vessel which Barton had plundered the previous day. They came

up with him in the Downs. The dread with which the name of the great Leith

sailorman had filled the English seamen is well seen in the reply a

sxteenth-century baliadist puts into the mouth of this skipper, Henry

Hunt, when requested by the Howards to steer their ships to Barton’s

haunts:-

"Were ye but twenty ships, and

he but one,

I swear by kirk, and bower, and hall,

He would overcome them every one,

If once his beams they do downfall."

On approaching Barton the English vessels

showed neither colours nor ensigns as was the rule with all ships, and

especially ships of war even then, but put up willow wands on their masts,

"As merchants use that sayle the sea,"

the old balladist tells us, but the beams

and other contrivances on Barton’s ship for overwhelming an enemy’s

deck are a pure invention on his part to add to the dramatic effect of his

story. Barton, in no way dismayed by the odds against him, boldly engaged

the enemy, and with his whistle suspended about his neck by a chain of

gold encouraged his men in the desperate conflict. With such opponents as.

the Howards, Barton well knew that the battle could only end with the

death or capture of himself or them.

"‘Fight on, my men,’

Sir Andrew says,

‘And never flinch before the foe;

And stand fast by St. Andrew’s Cross

As long’s you hear my whistle blow.’"

By St. Andrew’s Cross he

meant the Scottish flag or ensign. Easily distinguished by his rich dress

and bright armour, Barton became a special target for his enemies’

marksmen. He was mortally wounded early in the fight, but even then

continued to encourage his men with his whistle as long as life remained

to him. At length his whistle was heard no longer, and, on the Howards

boarding his vessel, they found that the gallant Leith captain was slain.

Thus died Andrew Barton, the most famous and brilliant sailorman that ever

sailed from the Port of Leith in an age when Leith mariners had hardly any

rivals, and might with truth be said to have held

"From Noroway’s

shores to Cape de Verde,

The mastery of the deep."

His ship, the Lion, was

carried into the Thames, and became, after the Great Harry, the

largest man-of-war in the English navy—a remarkable tribute to the Port

of Leith and the enterprise of her daring skippers.

James sent a herald to King

Henry to demand redress for the slaughter of his favourite officer in time

of peace, and compensation for the loss of his ships. Henry haughtily

replied that the fate of pirates should be no cause of dispute between

princes, an answer that only aggravated the insult to the Scottish flag,

for Barton, as Henry well knew, was no more pirate than the Howards

themselves. The English king, indeed, freed Barton’s crew, giving them a

small sum to defray the cost of their homeward journey; but this failed to

satisfy King James, and the dispute was finally fought out on Flodden

Field.

The rocks and shoals of the

Northumberland coast sent many a Scottish ship to its doom in those old

days of unlighted and uncharted seas. There in the reign of James Ill.,

off Bamborough, was wrecked the great trading barge of the good Bishop

Kennedy of St. Andrews, and there, too, was dashed "in Hinders"

one of James IV.’s ships, the Treasurer, no doubt named in honour

of Sir Robert Barton, the King’s Lord High Treasurer, who had purchased

her in Dieppe. In Embleton Bay, just north of the great ruined castle of

Dunstanburgh, there lies a rock a foot or two beneath the yellow sand

whose interest for Leithers is very great.

It is only uncovered at

long intervals by the wash of the waves, and then by the same agency

buried again. A few years ago, while exposed to view, its surface showed

in ancient rudely carved letters the famous name of "Andrea

Barton." A rubbing of this inscription has been taken in case it

should not again see the light. Embleton Bay must often have been familiar

with the sight of Barton’s flag as he sailed southward from the Forth,

it may be on some venture against the Portingals. But who carved the hero’s

name on the surface of this now hidden rock, whether he himself to

commemorate some victory over the English, or whether some admiring

follower as he rode at anchor in the bay, we may never know. The rock

evidently has some secret to reveal, but what that secret is has remained

undiscovered.

That the incident has been

forgotten is typical of most of the exploits of our Scottish

"Drake," for although rehearsed with pride round the winter fire

in the Leith of the brave days of James IV. they have long ago passed out

of memory. Some of them may again be revealed by as yet unpublished papers

in the State archives of Portugal. But the Bartons were an able race. and

their fame did not die when James IV.’s most brilliant sailorman fell in

the unequal conflict with the Howards in August 1511. His brothers Robert

and John, only just less celebrated than himself, had been associated with

him in some of his exploits against the Portuguese. They continued and

maintained the family fame; and the fighting Bartons of Leith were known

and held in wholesome respect by all the seafaring folk of Western Europe.

In 1513 the English

ambassador complained to James IV. that the Bartons had done Englishmen so

much harm, perhaps by way of reprisal for the slaughter of their brother

Andrew, that they were greatly excited against them. "England has

sustained three times as much damage at sea from the Scots as they have

from us," wrote Lord Dacre, Henry’s able but unscrupulous commander

on the Border, with the Leith sailormen in his mind. No wonder Henry VIII.

wrote in his wrath to James IV.: "As to Hob à Barton and Davy

Falconer their deeds have shown what they be." They had. "Two

ships of Leith have taken seven prizes of the Islande Flote (the English

Baltic trading fleet) and taken them to Leith," wrote Dacre again to

Wolsey. Unless the Zealand Flote (the English merchant fleet trading with

Holland) be better guarded they will be in great danger." As long as

Leith continued to send forth such gallant sea captains English pirates

could no longer plunder Scottish ships and murder Scottish seamen as they

had done, and as they were to do again under the nerveless foreign policy

of James VI., when Scottish mariners were neither encouraged nor

supported, and the great race of Leith sailormen came to an end.

Ships voyaging to France,

unless they formed a considerable fleet, usually went North-about—that

is, they steered north instead of south on leaving the Forth, and sailed

through the Pentland Firth and down the west coast. Ships from France

often came no farther than Ayr, a frequent landing-place of French

ambassadors. Ayr was then the chief port on the "West Keys," as

the waters washing our southern and western shores were then called. From

Ayr the cargoes were sent overland to Stirling, whence they were sent down

the Forth to Leith. Most of the wine taken aboard the fleet of James IV.

before it sailed for France during the Flodden campaign was brought from

the "West Seys" by this route.

But the risks of attack by

the English fleet patrolling the Narrow Seas of the Strait of Dover and

the English Channel had no terrors for Robin Barton and his close friend

and companion, Davy Falconer, with whom he so often sailed in company.

"The six ships under the command of Hob à Barton (Robin Barton), the

Lord High Treasurer, and Davy Falconer," wrote Dacre to Surrey in

1512, "are ready decked to carry their determination through the

Narrow Seas to France." Some times their daring cost them dear, for

after such information as that of Dacre’s the English fleet lay in wait

for the bold Leithers. It failed to find them on the outward voyage, but

on their return Barton and Falconer, with whom Will BrownhilL another

daring Leith navigator, was now sailing, ran plump into the whole English

fleet. Brownhill used to boast that he never encountered an English ship

at sea without fighting her. On this occasion, however, it was the English

who encountered him, and a hot time they gave him.

The odds were such that the Leith

men’s only chance was to dash through the English host as best they

could. Barton and the redoubtable Will Brownhill won through with the

utmost difficulty, but Falconer was captured and his ship "drounit"

or sunk. Falconer was "shrewitly handellit," by which phrase we

readily understand he was by no means chivalrously treated. Certainly the

English had suffered much at his hands. He was taken to London and safely

lodged in prison, where Henry VIII. determined that "for his manifold

piracies "—he would have been more truthful had he said for having

outmatched the English at their own game—Falconer should die.

But the Shore of Leith had

not yet seen the last of Falconer’s flag. Among the Port’s

sea-captains none had a warmer place in King James’s heart than Davy

Falconer, his "familiar servant," as he called him. Perhaps the

King saw in this seaman’s dash and spirit something akin to his own,

for, like all great sailormen, Falconer seems to have believed that no

seaman was worthy of the name who was not bold even to rashness. With the

aid of Lord Dacre, Henry’s ablest and most distinguished officer on the

Borders, James effected Falconer’s release, but beyond this nothing more

is told us. We must ever lament the scant

records that tell us so little of the gallant deeds of those bold Leith

sailormen, who raised Scotland’s name on the sea to such a pitch of fame

in those brave days of old. We could have wished that that graphic and

picturesque chronicler, Pitscottie, had been less curious about the

details of the Great Michael, and more interested in the exploits

of her daring and clever skipper, Robin Barton, and his seafaring friends

like Davy Falconer. Had Pitscottie, like another Hakluyt, gone in and out

among the Leith sailormen and recorded for later generations the moving

tales of their adventures, what a stirring chapter might we not have

possessed to-day about their exploits, and in what a setting of romance

would we see them when viewed through the long vista of over four hundred

years!

Like Sir Andrew Wood, Robert Barton

became a feudal baron, for in 1507 James IV. not only knighted him, but,

for his great services, gave him a gift of the lands of Barnton beside

Cramond. From over the corbelled parapet wall of the ancient keep that

stood here in Barton’s time he would have long sea views beyond the May

and the Bass to remind him of his stirring adventures of younger days.

The Woods, the Bartons, the

Napiers of Merchiston, and the Touris of Inverleith are among the earliest

instances in our history of merchants becoming great landowners, and

taking their place among the aristocracy without relinquishing their

merchandising, as custom would have compelled them to do in France or

Germany. Here we see the influence of such centres of trade and commerce

as Edinburgh and Leith in overthrowing the old feudalism, with its

mediaival notions about the profession of arms being the only fit

occupation for a gentleman. All the noble families in and around our

neighbourhood to-day, with two notable exceptions— those of Buccleuch

and Lothian—were founded by Edinburgh and Leith traders and merchants.

Sir Robert Barton’s training in commerce gave him great skill in money

matters and the keeping of accounts. It was for this reason be was made

Lord High Treasurer or Comptroller and Master of the Mint. We have a

pen-portrait of him in a letter from the English ambassador in Scotland to

Wolsey, in which we are shown Barton as a man of great wealth for a

Scotsman. He still sent shipping ventures to the Netherlands, France, and

the Baltic, but he himself now seldom voyaged over the seas.

Some of his ships, like the Black

Bargue of Abbeville, were seized by pirates, and the crews and factors

shamefully used. He became a generous friend to Margaret Tudor after the

catastrophe of Flodden, giving her of his ample means when she was often

penniless through her own imprudence and dishonest tenants refusing to pay

to her their rents. He was " ane very pyrett and sey-revare

comptroller," said Gavin Douglas, the son of the traitor

Bell-the-Cat, to Henry VIII.; but no patriotic Scot and officer of the

Crown at this time, however wise and able, could be good in the eyes of a

Douglas. Barton continued to live far into the reign of James V., when he

took a leading part in opposing the restrictions the Edinburgh merchant

burgesses placed upon the freedom of the Leith mariners.

Sir Robert Barton died in

1538. He was succeeded by his son, of the same name as himself, who added

the princely domain of Barnbongle and Dalmeny to that of Barnton by

marrying Barbara Moubray, the only daughter and heiress of the long and

noble line of the Moubrays, whose ancestor, Sir Philip, had held Stirling

Castle for Edward I. down to the day of Bannockburn. On his marriage

Robert Barton assumed the name and arms of Moubray; but in the days of

Queen Mary the fortunes of the family began to decline, and one by one

they had to part with their estates, until at last, in 1614, they had even

to sell Barnbougle. Barnton was purchased by Lord Balmerino, who by his

acquisition of the lands of Restalrig in 1604 had become laird of that

barony in place of the Logans.

While the Bartons and Sir

Andrew Wood are the best known and most famous of the Leith sea captains

of the days of James IV., they were not the only mariners of note who

belonged to the Port. A goodly number of others might be named, who in

their day were only less famous than the great captains whose names are so

familiar to all. Some of these have already appeared in this history.

There were Sir Alexander Makkison and Will Brownhill. There was Will

Merrymouth, whose daring in fight and skill in seamanship had won him the

soubriquet of "King of the Sea," and then there was the bold and

intrepid Davy Falconer, of whose adventurous career something has already

been said. He appears along with Sir Robert Barton as one of the heroes in

The Yellow Frigate, James Grant’s fascinating romance about the

Leith "Sea-dogs" of the days of James IV., as Sir David Falconer

of Bo’ness.

But, like Andrew Barton,

Falconer never seems to have had the honour of knighthood, and there is

little doubt he was of the family of Peter Falconer who founded and

endowed the altar to St. Peter in the, Lady Kirk of Leith in 1490. He had

no sooner been released by the English in 1512 than he sailed for France.

Returning later in the year he hugged the dangerous Flemish and Dutch

coasts so as to avoid the English, and then, driven before a terrific

storm, sailed straight across the North Sea and entered the Firth on a

dark night in December. Finding it impossible to make the Port of Leith,

Falconer, who was at the helm, ran before the gale right up the Firth away

beyond the Ferry, but fired two guns as he passed the harbour mouth. These

so greatly alarmed the burgesses of Edinburgh that for three hours

together they rang the common bell, which still strikes the hours in St.

Giles’ spire, although it has been recast twice since those days, and

every man, donning his armour, rushed to the City Cross in the belief that

the English were in the Forth.

Davy Falconer, like all the

Leith sailormen, was passionately loyal to king and country. When James V.

had freed himself from the hated thraldom of the Douglases, and was

besieging the traitorous brood in their stronghold of Tantallon, Davy

Falconer, from his experience in ship’s guns, went as captain of the

artillery, but the massive towers defied all attempts to capture them

despite the efforts of "many ingenious men, both Scotch and French,

although never so much was ever done in vain to win one house." James

gave up the siege and returned with the army to Edinburgh, leaving a

company of foot to follow with the artillery.

But "that same night a

little after moonrise" Angus sallied forth with eightscore horse and

attacked and defeated them, slaying Davy Falconer, who was gallantly

covering the retreat, "the principal captain of foot and their best

man-o’-warsman on the sea," wrote the English ambassador Magnus,

not without the feeling that his news would not be unwelcome to his royal

master. And so by the hands of the traitor Earl of Angus and his Scots

died Davy Falconer, one of the most gallant and chivalrous of that choice

company of great Leith sea captains who were ever loyal to the king and

devoted to the service of their country, and who did so much for

Scotland's name and fame on the sea when there was little, if any,

patriotism among those in high places.

|