|

IN his endeavours to make

Scotland a power on the sea James IV. was ably seconded by the sailormen

of Leith. The number of noted sea-captains belonging to the Port at this

time was out of all proportion to its size. This was owing to Leith being

the port, not only for the larger town of Edinburgh, but also, now that

Berwick had become an English town, for the whole south-east of Scotland,

and especially for the wool trade of the great Border abbeys. Then, again,

commerce was the monopoly in those days of the freemen of the royal burghs

only, so that in an unfree town like Leith sailoring was the occupation

that offered the greatest opportunities of wealth and advancement to lads

of push and enterprise.

In no other port of Europe

at this time of equal size could there have been found more daring

captains, and few could have rivalled Leith in her number of bold and

skilful mariners, for seafaring was in their blood. It had been the

occupation of the men folk of many Leith families through long

generations, and even in our days of steamships, when the sailorman is

degenerating into the mere deck hand, there are still a few families in

the town with whom seafaring has been a tradition for centuries. The navy

of James IV. could neither have been built nor manned had he not had the

sailor-men of Leith behind him.

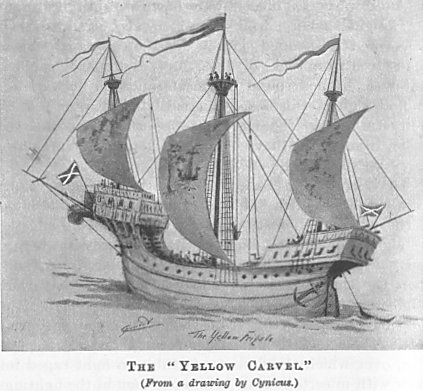

Among Leith’s noted

mariners at this time none had won a greater name for himself than Sir

Andrew Wood of Largo, who was a Leith man born and bred. He first comes

upon the stage of history in the reign of James III. as the commander of

two ships of about three hundred tons each—the Flower and the Yellow

Carvel. The Yellow Carvel belonged to the king, and had

formerly been commanded by the veteran John Barton. Wood hired this vessel

at so much a voyage, or even at so much per annum, as was the custom of

those days, but the Flower was his own vessel.

With these two ships Wood

made frequent trading voyages to France, and still more to the Low

Countries. In Andrew Halyburton’s ledger we get glimpses of both him and

the Flower in the old Dutch town of Bergen-op-Zoom, then one of the

most flourishing towns in Holland, though now unimportant. His reputation

for seamanship had early recommended him to the favour of the king, who

bestowed upon him the lands of Largo on the condition that he should

accompany the king and queen to the holy well and shrine of St. Adrian on

the Isle of May as often as he was required to do so.

Wood had developed a great

genius for naval warfare by his frequent encounters with Dutch, English,

and Portuguese pirates in defence of his ships and their cargoes. From his

many victories over these enemies he has been called the Scottish

"Nelson" of his time. He was the trusted servant of James III.,

by whom he had been employed on several warlike missions, which he carried

out with fidelity to his king and honour to himself. Two of these

expeditions were his successful defence of Dumbarton castle against the

fleet of Edward IV. in 1481, and his attack

on the fleet of Sir Edward Howard, which the

English king had sent to do as much mischief as it could along the shores

of the Firth of Forth. It was for these important services against the

English that James III. gave Wood a part of the lands of Largo, which he

had previously occupied as a tenant of the king.

In those days money was scarce and rents were usually

paid in kind— that is, in the produce of the land. The feu-duties of

much land in Leith are still reckoned in amounts of grain and vary with its

market price. The Black Vaults of Logan of Coatfield were partly used for

the storage of such rents.

And so we find Sir

Andrew Wood, in the days when he was only tenant of

Largo, and not laird, constantly engaged in shipping grain from Largo to

Leith. Grain, then as now, bulked considerably in Leith’s imports; but

whereas most of it now comes from abroad, in the days of James III., and

for several centuries after, it was all, except in times of dearth, home

grown. Scotland in those days was self-sustaining—that is, she grew all

her own food.

Sir Andrew Wood is no less noted for his faithful

adherence to James III. when opposed by his rebellious and traitorous

nobles, like old "Bell-the-Oat," than for his skill and courage

as a naval commander. In his flight from the battlefield of Sauchieburn

the ill-fate king is supposed to have been making his way to the

shores of the Forth opposite Alloa, where Sir Andrew had gone with his two

ships in aid of his royal master. All that long sunny June afternoon he

kept several boats close by the shore to receive the king if defeat should

overtake his arms, as it did, but the tragedy at Beaton Mill rendered

the loyal sailorman’s vigil vain.

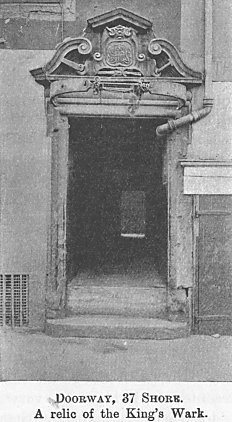

After the battle the insurgent lords proclaimed James

IV. king at Stirling, and then marched east to the capture of Edinburgh

Castle. It was for this purpose

they encamped on Leith Links for two days, and at the same time appear to

have occupied the King’s Wark on the Shore. The fate of James III. was

as yet unknown, but, as report declared that Sir Andrew Wood’s ships had

been seen taking on board men wounded in the battle, it was thought the

king might have found refuge with their gallant commander aboard the Yellow

Carvel. Wood had by this time come to anchor in Leith Roads some two

miles off the shore. Sir Andrew was requested to come before the young

King James IV. and his council to tell what he knew of the fate of James

III., but this the wary seaman refused to do until two hostages of rank

were sent aboard the Yellow Carvel to ensure his safe return.

On the arrival of the hostages—Lord Seton and Lord

Fleming—aboard his ship the loyal and gallant Wood, seated in his great

barge, at once steered for the Shore, the oars glittering in the sunlight

as with measured stroke the boat swept past the Mussel Cape, now crowned

by the Martello Tower, and, entering the old harbour, made straight for

the landing-stage opposite the King’s Wark. Here Wood boldly confronted

the haughty confederate lords. When asked by the young and now repentant

king if his father was aboard his ships, Wood replied that he wished he

were, when he would defend and keep him scathless from all the traitors

who had cruelly murdered him.

The traitor

"Bell-the-Cat" and the other rebel lords scowled angrily at

these bold words, but, fearful of what might befall their two friends in

pledge aboard the ships, could not further resent them. Finding they could

make nothing of the undaunted Wood, they dismissed him to his ships, where

his men, impatient and alarmed at his delay, were about to swing the two

hostages from the yardarm in the belief that some treachery had befallen

their much-loved commander. Authentic news of the cruel fate that had

overtaken James III. soon came to hand, and then Sir Andrew Wood gave in

his allegiance to his successor, and became one of his most trusted

friends and counsellors. In the work of constructing royal dockyards at

Leith and Newhaven, and in his ambition to make Scotland’s name a power

on the sea, James IV. found no more wise and powerful supporter than the

brave Sir Andrew Wood.

The year after James IV.

ascended the throne five English ships entered the Firth of Forth, ravaged

the shores of Fife and the Lothians, and did much damage among trading

vessels making for Leith and other ports on the Forth. Now, while there

was never really peace between the two countries on the high seas, such an

outrage as this James determined should not go unpunished. He ordered Sir

Andrew Wood to go in pursuit of the enemy. With never a thought of the

odds against him, that gallant captain at once weighed anchor, and, under

a heavy press of sail decorated with the royal arms and those of the brave

Sir Andrew himself, as you may see in the pictures of the Yellow cartel

and the Great Michael, his two stately ships stood down the

Firth with a favouring breeze behind them.

All was bustle and activity

on board, getting the decks cleared for action, which, in those stirring

and romantic days, meant rather cumbering them with the guns of the

arquebusiers. These had all to be set on their stands to sweep the enemy’s

decks and cripple her sails and rigging in order to render her

unmanageable. Sir Andrew and his officers were harnessed in full armour

like knights ashore, while the men, accoutred in their jacks or

steel-padded jackets and steel caps, armed themselves from racks of axes,

guns, and boarding pikes, that were framed round the masts and the

bulwarks of poop and quarter-deck. The cross-bowmen were sent to their

stations in the fighting-tops or cages round the masts, from which they

could shoot arrows or hurl down heavy missiles on the enemy’s deck.

The

Yellow Cartel and her consort, the Flower, came up with the

English ships off Dunbar. All undaunted by the unequal contest, Wood at

once blew his whistle, the signal for action, and the battle forthwith

began. The boarders stood by with the grappling irons, and, when the ships

closed in upon one another, they were caught by the irons below and by the

hooks for the same purpose projecting from the ends of the yardarms aloft.

Their locked hulls then formed one great platform, over which the fierce

and stubborn fight raged for hours with uncertain issue, while the men in

the fighting-tops threw down missiles on the mass of swaying combatants

below as they saw opportunity. At length the skill and courage of the

Leith sailormen prevailed, and overcame the superior force of the English.

With the fighting-tops of his now crippled ships gay with streamers and

banners that even swept the surface of the sea, Wood convoyed the five

English prizes in triumph to the Port, and the name of the great Leith

captain, so the story

goes, "became a by-word and a terror to all the shippers and mariners

of England."

Sir Andrew was richly

rewarded by James for his great services, and in some measure to make up

for the losses he had sustained, and, as no castle could be built without

the king’s permission, licence was given him to erect such at Largo as a

defence against English pirates who, in raiding the shores of Fife, would

never fail to make his dwelling a special object of attack. This castle,

according to the same old chronicler, he is said to have compelled some

English pirates captured at sea to build by way of ransom.

Henry VII., indignant at

the disgrace brought upon the English flag by so humiliating a defeat, is

said to have offered an annual pension of £1,000 to any English captain

who should capture the ships of Wood and take him prisoner. Now, unless

history utterly belies the character of Henry VII., such a story is

entirely out of keeping with all we know of him, for he was a man of peace

and loved money even to miserliness. Be that as it may, one Stephen Bull,

when other English captains had declined to attempt so risky an

enterprise, equipped three ships, and determined to bring Wood to London

dead or alive. We know little of Bull beyond the fact that he was knighted

by Sir Edward Howard in Brittany in 1512, and we know nothing at all of

his three ships, except that they were neither king’s ships nor in the

king’s service.

But we have not read aright

the story of the death of the Leith sailormen in days of yore if we have

not learned that for merchant ships to be guilty of piratical attacks upon

those of other nations, and to be sometimes captured by those they

attacked, was a very common incident on the high seas in those lawless

times. Indeed so common was it that it had been a long-established custom

on the North Sea for mariners thus captured, when they were not made to

"walk the plank," as they at times were, to be ransomed by their

friends at the very moderate charge of twenty shillings a mariner and

forty shillings the master or skipper.

With his three ships Bull

sailed for the Forth in July 1490, and, entering the Firth, lay to behind

the Isle of May. In the belief that peace had been established with

England Wood had sailed for Flanders, partly by way of trade and partly as

convoy to the merchant fleet. On a fine sunny morning in August Sir Andrew

Wood’s two ships hove

in sight, and all unconscious of the presence of the lurking enemy,

steered their way towards the Forth. But no sooner did Wood perceive the

English ships with the white flag and red cross of St. George than he at

once gave the signal for immediate action, and fought "fra the

ryssing of the sun till the gaeing doun of the same in the lang simmer’s

day, quhile afi the men and women that dwelt near the coast syd stood and

beheld the fighting, quhilk was terrible to sie."

This running fight was kept

up for three days, when victory once more declared itself on the side of

the seemingly invincible Leith captain, and, after taking the ships to

Dundee, Wood and his prizes eventually came to Leith, bringing sorrow as

well as joy to the town, for many a member of his crew had fallen in the

desperate three days’ encounter. These two naval victories of Sir Andrew

Wood by which he is popularly known rest solely on the picturesque

narrative of the gossipy Pitscottie, who is not generally relied on unless

corroborated by other writers. But we must remember that Pitscottie was

near neighbour to the Woods at Largo, and the familiar friend of Sir

Andrew’s second and more distinguished son John, who played a notable

part in the service of James V. Besides, he was intimate with Sir Robert

Barton, the first skipper of the Great Michael, and from him he got

all the details of that famous ship.

We have seen that Sir

Andrew Wood had much to do with the construction of the king’s dockyards

at Leith and at Newhaven, and with the building of that navy in which

James IV. was so interested. It was he who superintended the construction

and equipment of the Great Michael, the largest ship built either

in England or Scotland up to that time. She was the special pride of the

Leithers, who looked on her as one of the wonders of the age, as indeed

she was. When the Great Michael was launched at Newhaven in 1511,

Sir Andrew was made her quartermaster or principal captain, with Robert

Barton under him as skipper or second captain.

On

the outbreak of the Flodden campaign the command of this great vessel, the

flagship of the fleet, was by a fatal error given, not to a skilful seaman

like Sir Andrew Wood, or to Robert Barton, but to the Earl of Arran, as in

feudal countries like Scotland any great office of state like that of Lord

High Admiral had, in accordance with the customs of the age, to belong to

the great feudal aristocracy. The fleet was as handsornely equipped as any

British squadron of the present day, the complement of men including

chaplains and "barbers," who in Scotland at that time, as

everywhere else in Europe, combined with that trade the profession of

surgeon, their guild being known as the "Incorporation of Chirurgeons

and Barboures." The barber’s pole with a brass bleeding-dish

hanging from near its end was the sign of the Surgeon-Barbers’ Guild in

olden days. On

the outbreak of the Flodden campaign the command of this great vessel, the

flagship of the fleet, was by a fatal error given, not to a skilful seaman

like Sir Andrew Wood, or to Robert Barton, but to the Earl of Arran, as in

feudal countries like Scotland any great office of state like that of Lord

High Admiral had, in accordance with the customs of the age, to belong to

the great feudal aristocracy. The fleet was as handsornely equipped as any

British squadron of the present day, the complement of men including

chaplains and "barbers," who in Scotland at that time, as

everywhere else in Europe, combined with that trade the profession of

surgeon, their guild being known as the "Incorporation of Chirurgeons

and Barboures." The barber’s pole with a brass bleeding-dish

hanging from near its end was the sign of the Surgeon-Barbers’ Guild in

olden days.

From the date of this

expedition we hear little more of Sir Andrew Wood. The great sailor died

two years later, in 1515. He was buried in the family aisle in the ancient

parish church of Largo, where his tomb is marked by a plain inscribed

stone let into the floor. He has often been confused with his eldest son,

who bore the same name as himself, with the result that Sir Andrew has

been represented as living to a very old age. To this confusion, together

with the fact that the remains of some great ditch, moat, or other

earthwork seem to lead from his now ruined tower at Largo in the direction

of the village, we owe the picturesque legend that, when enfeebled

by an old age he never reached, he caused a canal to be formed from his

castle to the parish church which stands at the entrance to the ancient

avenue, and that on this canal he used to sail in state to church in his

barge, rowed by old pensioners with whom he had fought so many brave

fights aboard that most storied ship in Scottish history, the Yellow

Carvel.

|