|

MONTROSE now entertained

confident expectations that many of the royalists of the surrounding

country who had hitherto kept aloof would join him; but after remaining

three days at Perth, to give them an opportunity of rallying round his

standard, he had the mortification to find that, with the exception of

Lords Dupplin and Spynie, and a few gentlemen from the Carse of Gowrie,

who came to him, his anticipations were not to be realized. The spirits of

the royalists had been too much subdued by the seventies of the

Covenanters for them all at once to risk their lives and fortunes on the

issue of what they had long considered a hopeless cause; and although

Montrose had succeeded in dispersing one army with a greatly inferior

force, yet it was well known that that army was composed of raw and

undisciplined men, and that the Covenanters had still large bodies of

well-trained troops in the field.

Thus disappointed in his

hopes, and understanding that the Marquis of Argyle was fast approaching

with a large army, Montrose crossed the Tay on the 4th of September,

directing his course towards Coupar-Angus, and encamped at night in the

open fields near Collace. His object in proceeding northward was to

endeavour to raise some of the loyal clans, and thus to put himself in a

sufficiently strong condition to meet Argyle. Montrose had given orders to

the army to march early next morning, but by break of day, and before the

drums had beat, he was alarmed by an uproar in the camp. Perceiving his

men running to their arms in a state of fury and rage, Montrose,

apprehensive that the Highlanders and Irish had quarrelled, immediately

rushed in among the thickest of the crowd to pacify them, but to his great

grief and dismay, he ascertained that the confusion had arisen from the

assassination of his valued friend Lord Kilpont. He had fallen a victim to

the blind fury of James Stewart of Ardvoirlich, with whom he had slept the

same night, and who had long enjoyed his confidence and friendship.

According to Wishart, wishing to ingratiate himself with the Covenanters,

he formed a design to assassinate Montrose or his major-general,

Macdonald; and endeavoured to entice Kilpont to concur in his wicked

project. He, therefore, on the night in question, slept with his lordship,

and having prevailed upon him to rise and take a walk in the fields before

daylight, on the pretence of refreshing themselves, he there disclosed his

horrid purpose, and entreated his lordship to concur therein. Lord Kilpont

rejected the base proposal with horror and indignation, which so alarmed

Stewart that, afraid lest his lordship might discover the matter, he

suddenly drew his dirk and mortally wounded Kilpont. Stewart, thereupon,

fled, and thereafter joined the Marquis of Argyle, who gave him a

commission in his army. (Wishart, p. 84. — Stewart’s descendant, the

late Robert Stewart of Ardvoirlich, gives an account of the above

incident, founded on a "constant tradition in the family."

tending to show that his ancestor was not so much a man of base and

treacherous character, as of "violent passions and singular

temper." James Stewart, it is said, was so irritated at the Irish,

for committing some excesses on lands belonging to him, that he challenged

their commander, Macdonald, to single combat. By advice of Kilpont,

Montrose arrested both, and brought about a seeming conciliation. When

encamped at Collace, Montrose gave an entertainment to his officers, on

returning from which Ardvoirlich, "heated with drink, began to blame

Kilpont for the part he had taken in preventing his obtaining redress, and

reflecting against Montrose for not allowing bins what he considered

proper reparation. Kilpont, of course, defended the conduct of himself and

his relative, Montrose, till their argument came to high words, and

finally, from the state they were both in, by an easy transition, to

blows, when Ardvoirlich, with his dirk, struck Kilpont dead on the

spot." He fled, leaving his eldest son, Henry, mortally wounded at

Tippermuir, on his death-bed.—lntrod. to Legend Montrose).

Montrose now marched upon

Dundee, which refused to surrender. Not wishing to waste his time upon the

hazardous issue of a siege with a hostile army in his rear, Montrose

proceeded through Angus and the Mearns, and in the course of his route was

joined by the Earl of Airly, his two sons, Sir Thomas and Sir David

Ogilvie, and a considerable number of their friends and vassals, and some

gentlemen from the Mearns and Aberdeenshire. This was a seasonable

addition to Montrose’s force, which had been greatly weakened by the

absence of some of the Highlanders who had gone home to deposit their

spoils, and by the departure of Lord Kilpont’s retainers, who had gone

to Menteith with his corpse.

After the battle of

Tippermuir, Lord Elcho had retired, with his regiment and some fugitives,

to Aberdeen, where he found Lord Burleigh and other commissioners from the

convention of estates. As soon as they heard of the approach of Montrose,

Burleigh, who acted as chief commissioner, immediately assembled the

Forbeses, the Frasers, and the other friends of the covenanting interest,

and did everything in his power to gain over to his side as many persons

as he could from those districts where Montrose expected assistance. In

this way Burleigh increased his force to 2,500 foot and 500 horse, but

some of these, consisting of Gordons, and others who were obliged to take

up arms, could not be relied upon.

When Montrose heard of

these preparations, he resolved, notwithstanding the disparity of force,

his own army now amounting only to 1,500 foot and 44 horse, to hasten his

march and attack them before Argyle should come up. On arriving near the

bridge of Dee, he found it strongly fortified and guarded by a

considerable force. He did not attempt to force a passage, but, directing

his course to the west, along the river, crossed it at a ford at the Mills

of Drum, and encamped at Crathas that night (Wednesday, 11th September).

The Covenanters, the same day, drew up their army at the Two Mile Cross, a

short distance from Aberdeen, where they remained till Thursday night,

when they retired into the town. On the same night, Montrose marched down

Deeside, and took possession of the ground which the Covenanters had just

left.

On the following morning,

viz., Friday, 13th September, about eleven o’clock, the Covenanters

marched out of Aberdeen to meet Montrose, who, on their approach,

despatched a drummer to beat a parley, and sent a commissioner along with

him bearing a letter to the provost and bailies of Aberdeen, commanding

and charging them to surrender the town, promising that no more harm

should be done to it; "otherwise, if they would disobey, that then he

desired them to remove old aged men, women, and children out of the way,

and to stand to their own peril". Immediately on receipt of this

letter, the provost called a meeting of the council, which was attended by

Lord Burleigh, and, after a short consultation, an answer was sent along

with the commissioner declining to surrender the town. On their return the

drummer was killed by the Covenanters, at a place called Justice Mills;

which violation of the law of nations so exasperated Montrose, that he

gave orders to his men not to spare any of the enemy who might fall into

their hands. His anger at this occurrence is strongly depicted by

Spalding, who says, that "he grew mad, and became furious and

impatient."

As soon as Montrose

received notice of the refusal of the magistrates to surrender the town,

he made the necessary dispositions for attacking the enemy. From his

paucity of cavalry, he was obliged to extend his line, as he had done at

Tippermuir, to prevent the enemy from surrounding or outflanking him with

their horse, and on each of his wings he posted his small body of horsemen

along with select parties of musketeers and archers. To James Hay and Sir

Nathaniel Gordon he gave the command of the right wing, committing the

charge of the left to Sir William Rollock, all men of tried bravery and

experience.

The Covenanters began the

battle by a cannonade from their field-pieces, and, from their commanding

position, gave considerable annoyance to the royal forces, who were very

deficient in artillery. After the firing had been kept up for some time,

Lord Lewis Gordon, third son of the Marquis of Huntly, a young man of a

very ardent disposition, and of a violent and changeable temper, who

commanded the left wing of the Covenanters, having obtained possession of

some level ground where his horse could act, made a demonstration to

attack Montrose’s right wing; which being observed by Montrose, he

immediately ordered Sir William Rollock, with his party of horse, from the

left wing to the assistance of the right. These united wings, which

consisted of only 44 horse, not only repulsed the attack of a body of 300,

but threw them into complete disorder, and forced them to retreat upon the

main body, leaving many dead and wounded on the field. Montrose restrained

these brave cavaliers from pursuing the body they had routed, anticipating

that their services might be soon required at the other wing; and he was

not mistaken, for no sooner did the covenanting general perceive the

retreat of Lord Lewis Gordon than he ordered an attack to be made upon the

left wing of Montrose’s army; but Montrose, with a celerity almost

unexampled, moved his whole cavalry from the right to the left wing,

which, falling upon the flank of their assailants sword in hand, forced

them to fly, with great slaughter. In this affair Montrose’s horse took

Forbes of Craigievar and Forbes of Boyndlie prisoners.

The unsuccessful attacks on

the wings of Montrose’s army had in no shape affected the future fortune

of the day, as both armies kept their ground, and were equally animated

with hopes of ultimate success. Vexed, but by no means intimidated by

their second defeat, the gentlemen who composed Burleigh’s horse

consulted together as to the best mode of renewing the attack; and, being

of opinion that the success of Montrose’s cavalry was owing chiefly to

the expert musketeers, with whom they were interlined, they resolved to

imitate the same plan, by mixing among them a select body of foot, and

renewing the charge a third time, with redoubled energy. But this scheme,

which might have proved fatal to Montrose, if tried, was frustrated by a

resolution he came to, of making an instant, and simultaneous attack upon

the enemy. Perceiving their horse still in great confusion, and a

considerable way apart from their main body, he determined upon attacking

them with his foot before they should get time to rally; and galloping up

to his men, who had been greatly galled by the enemies’ cannon, he told

them that there was no good to be expected by the two armies keeping at

such a distance—that in this way there was no means of distinguishing

the strong from the weak, nor the coward from the brave man, but that if

they would once make a home charge upon these timorous and effeminate

striplings, as he called Burleigh’s horse, they would never stand their

attack. "Come on, then," said he, "my brave fellow

soldiers, fall down upon them with your swords and muskets, drive them

before you, and make them suffer the punishment due to their perfidy and

rebellion." These words were no sooner uttered, than

Montrose’s men rushed forward at a quick pace and fell upon the enemy,

sword in hand. The Covenanters were paralyzed by the suddenness and

impetuosity of the attack, and, turning their backs, fled in the utmost

trepidation and confusion, towards Aberdeen. The slaughter was tremendous,

as the victors spared no man. The road leading from the field of battle to

Aberdeen was strewed with the dead and the dying; the streets of Aberdeen

were covered with the bodies, and stained with the blood of its

inhabitants. "The lieutenant followed the chase into Aberdeen, his

men hewing and cutting down all manner of men they could overtake, within

the town, upon the streets, or in the houses, and round about the town, as

our men were fleeing with broad swords, but (i.e. without) mercy or

remeid. Their cruel Irish, seeing a man well clad, would first tyr (strip)

him and save his clothes unspoiled, syne kill the man." In fine,

according to this writer, who was an eye-witness, the town of Aberdeen,

which, but a few years before, had suffered for its loyalty, was now, by

the same general who had then oppressed it, delivered up by him to be

indiscriminately plundered by his Irish forces, for having espoused the

same cause which he himself had supported. For four days did these men

indulge in the most dreadful excesses, "and nothing," continues

Spalding, was "heard but pitiful howling, crying, weeping, mourning,

through all the streets." Yet Guthry says that Montrose " shewed

great mercy, both pardoning the people and protecting their goods."

It is singular, that

although the battle continued for four hours without any determinate

result, Montrose lost very few men, a circumstance the more extraordinary

as the cannon of the Covenanters were placed upon advantageous ground,

whilst those of Montrose were rendered quite ineffective by being situated

in a position from which they could not be brought to bear upon the enemy.

An anecdote, characteristic of the bravery of the Irish, and of their

coolness in enduring the privations of war, has been preserved. During the

cannonade on the side of the Covenanters, an Irishman had his leg shot

away by a cannon ball, but which kept still attached to the stump by means

of a small bit of skin, or flesh. His comrades-in-arms being affected with

his disaster, this brave man, without betraying any symptoms of pain, thus

cheerfully addressed them :—" This, my companions, is the fate of

war, and what none of us ought to grudge: go on, and behave as becomes you

and, as for me, I am certain my lord, the marquis, will make me a trooper,

as I am now disabled for the foot service." Then, taking a knife from

his pocket, he deliberately opened it, and cut asunder the skin which

retained the leg, without betraying the least emotion, and delivered it to

one of his companions for interment. As soon as this courageous mar. was

able to mount a horse, his wish to become a trooper was complied with, in

which capacity he afterwards distinguished himself.

Hoping that the news of the

victory he had obtained would create a strong feeling in his favour among

the Gordons, some of whom had actually fought against him, under the

command of Lord Lewis Gordon, Montrose sent a part of his army towards

Kintore and Inverury, the following day, to encourage the people of the

surrounding country to declare for him; but he was sadly disappointed in

his expectations. The fact is, that ever since the appointment of Montrose

as lieutenant-general of the kingdom,—an appointment which trenched upon

the authority of the Marquis of Huntly as lieutenant of the north,—the

latter had become quite lukewarm in the cause of his sovereign; and,

although he was aware of the intentions of his son, Lord Lewis, to join

the Covenanters, he quietly allowed him to do so without remonstrance.

But, besides being thus, in some measure, superseded by Montrose, the

marquis was actuated by personal hostility to him on account of the

treatment he had formerly received from him; and it appears to have been

partly to gratify his spleen that he remained a passive observer of a

struggle which involved the very existence of the monarchy itself.

Whatever may have been Huntly’s reasons for not supporting Montrose, his

apathy and indifference had a deadening influence upon his numerous

retainers, who had no idea of taking the field but at the command of their

chief.

As Montrose saw no

possibility of opposing the powerful and well-appointed army of Argyle,

which was advancing upon him with slow and cautious steps, disappointed as

he had been of the aid which he had calculated upon, he resolved to march

into the Highlands, and there collect such of the clans as were favourably

disposed to the royal cause. Leaving Aberdeen, therefore, on the 16th of

September, with the remainder of his forces, he joined the camp at Kintore,

whence he despatched Sir William Rollock to Oxford to inform the king of

the events of the campaign, and of his present situation, and to solicit

him to send supplies.

We must now advert to the

progress of Argyle’s army, the slow movements of which form an

unfavourable contrast with the rapid marches of Montrose’s army. On the

4th of September, four days after the battle of Tippermuir, Argyle, who

had been pursuing the Irish forces under Macdonald, had arrived with his

Highlanders at Stirling, where, on the following day, he was joined by the

Earl of Lothian and his regiment, which had shortly before been brought

over from Ireland. After raising some men in Stirlingshire, he marched to

Perth upon the 10th, where he was joined by some Fife men, and Lord

Bargenny’s and Sir Frederick Hamilton’s regiments of horse, which had

been recalled from Newcastle for that purpose. With this increased force,

which now consisted of about 3,000 foot and two regular cavalry regiments,

besides ten troops of horse, Argyle left Perth on the 14th of September

for the north, and in his route was joined by the Earl Marshal, Lords

Gordon, Fraser, and Crichton, and other Covenanters. He arrived at

Aberdeen upon the 19th of September, where he issued a proclamation,

declaring the Marquis of Montrose and his followers traitors to religion

and to their king and country, and offering a reward of 20,000 pounds

Scots, to any person who should bring in Montrose dead or alive. Spalding

laments with great pathos and feeling the severe hardships to which the

citizens of Aberdeen had been subjected by these frequent visitations of

hostile armies, and alluding to the present occupancy of the town by

Argyle, he observes that "this multitude of people lived upon free

quarters, a new grief to both towns, whereof there was quartered on poor

old Aberdeen Argyle’s own three regiments. The soldiers had their

baggage carried, and craved nothing but house-room and fire. But ilk

captain, with twelve gentlemen, had free quarters, (so long as the town

had meat and drink,) for two ordinaries, but the third ordinary they

furnished themselves out of their own baggage and provisions, having store

of meal, molt and sheep, carried with them. But, the first night, they

drank out all the stale ale in Aberdeen, and lived upon wort

thereafter."

Argyle was now within half

a day’s march of Montrose, but, strange to tell, he made no preparations

to follow him, and spent two or three days in Aberdeen doing absolutely

nothing. After spending this time in inglorious supineness, Argyle put his

army in motion in the direction of Kintore. Montrose, on hearing of his

approach, concealed his cannon in a bog, and leaving behind him some of

his heavy baggage, made towards the Spey with the intention of crossing

it. On arriving at the river, he encamped near the old castle of

Rothiemurchus; but finding that the boats used in passing the river had

been removed to the north side of the river, and that a large armed force

from the country on the north of the Spey had assembled on the opposite

bank to oppose his passage, Montrose marched his army into the forest of

Abernethy. Argyle only proceeded at first as far as Strathbogie; but

instead of pursuing Montrose, he allowed his troops to waste their time in

plundering the properties and laying waste the lands of the Gordons in

Strathbogie and the Enzie, under the very eyes of Lord Gordon and Lord

Lewis Gordon, neither of whom appears to have endeavoured to avert such a

calamity. Spalding says that it was "a wonderful unnaturalitie in the

Lord Gordon to suffer his father’s lands and friends in his own sight to

be thus wreckt and destroyed in his father’s absence;" but Lord

Gordon likely had it not in his power to stay these proceedings, which, if

not done at the instigation, may have received the approbation of his

violent and headstrong younger brother, who had joined the Covenanters’

standard. On the 27th of September, Argyle mustered his forces at the Bog

of Gicht, when they were found to amount to about 4,000 men; but although

the army of Montrose did not amount to much more than a third of that

number, and was within twenty miles’ distance, he did not venture to

attack him. After remaining a few days in Abernethy forest, Montrose

passed through the forest of Rothiemurchus, and following the course of

the Spey, marched through Badenoch to Athole, which he reached on 1st

October.

When Argyle heard of the

departure of Montrose from the forest of Abernethy, he made a feint of

following him. He accordingly set his army in motion along Speyside, and

crossing the river himself with a few horse, marched up some distance

along the north bank, and recrossed, when he ordered his troops to halt.

He then proceeded to Forres to attend a committee meeting of Covenanters

to concert a plan of operations in the north, at which the Earl of

Sutherland, Lord Lovat, the sheriff of Moray, the lairds of Balnagown,

Innes and Pluscardine, and many others were present. From Forres Argyle

went to Inverness, and after giving some instructions to Sir Mungo

Campbell of Lawers, and the laird of Buchanan, the commanders of the

regiments stationed there, he returned to his army, which he marched

through Badenoch in pursuit of Montrose. From Athole Montrose sent

Macdonald with a party of 500 men to the Western Highlands, to invite the

laird of Maclean, the captain of clan Ranald, and others to join him.

Marching down to Dunkeld, Montrose himself proceeded rapidly through Angus

towards Brechin and Montrose.

Although some delay had

been occasioned in Montrose’s movements by his illness for a few days in

Badenoch, this was fully compensated for by the tardy motions of Argyle,

who, on entering Badenoch, found that his vigilant antagonist was several

days’ march a-head of him. This intelligence, however, did not induce

him in the least to accelerate his march. Hearing, when passing through

Badenoch, that Montrose had been joined by some of the inhabitants of that

country, Argyle, according to Spalding, "left nothing of that country

undestroyed, no not one four footed beast;" and Athole shared a

similar fate.

At the time Montrose

entered Angus, a committee of the estates, consisting of the Earl Marshal

and other barons, was sitting in Aberdeen, who, on hearing of his

approach, issued on the 10th of October a printed order, to which the Earl

Marshal’s name was attached, ordaining, under pain of being severely

fined, all persons, of whatever age, sex, or condition, having horses of

the value of forty pounds Scots or upwards, to send them to the bridge of

Dee, which was appointed as the place of rendezvous, on the 14th of

October, by ten o’clock, a.m., with riders fully equipped and armed.

With the exception of Lord Gordon, who brought three troops of horse, and

Captain Alexander Keith, brother of the Earl Marshal, who appeared with

one troop at the appointed place, no attention was paid to the order of

the committee by the people, who had not yet recovered from their fears,

and their recent sufferings were still too fresh in their minds to induce

them again to expose themselves to the vengeance of Montrose and his Irish

troops.

After refreshing his army

for a few days in Angus, Montrose prepared to cross the Grampians, and

march to Strathbogie to make another attempt to raise the Gordons; but,

before setting out on his march, he released Forbes of Craigievar and

Forbes of Boyndlie, on their parole, upon condition that Craigievar should

procure the liberation of the young laird of Drum and his brother from the

jail of Edinburgh, failing which, Craigievar and Boyndlie were both to

deliver themselves up to him as prisoners before the 1st of November. This

act of generosity on the part of Montrose was greatly admired, more

particularly as Craigievar was one of the heads of the Covenanters, and

had great influence among them. In pursuance of his design, Montrose

marched through the Meams, and upon Thursday, the 17th of October, crossed

the Dee at the Mills of Drum, with his whole army. In his progress north,

contrary to his former forbearing policy, he laid waste the lands of some

of the leading Covenanters, burnt their houses, and plundered their

effects. He arrived at Strathbogie on the 19th of October, where he

remained till the 27th, without being able to induce any considerable

number of the Gordons to join him. It was not from want of inclination

that they refused to do so, but they were unwilling to incur the

displeasure of their chief, who they knew was personally opposed to

Montrose, and who felt indignant at seeing a man who had formerly espoused

the cause of the Covenanters preferred before him. Had Montrose been

accompanied by any of the Marquis of Huntly’s sons, they might have had

influence enough to have induced some of the Gordons to declare for him;

but the situation of the marquis’s three sons was at this time very

peculiar. The eldest son, Lord Gordon, a young man "of singular worth

and accomplishments," was with Argyle, his uncle by the mother’s

side; the Earl of Aboyne, the second son, was shut up in the castle of

Carlisle, then in a state of siege; and Lord Lewis Gordon, the third son,

had, as we have seen, joined the Covenanters, and fought in their ranks.

In this situation of

matters, Montrose left Strathbogie on the day last mentioned, and took up

a position in the forest of Fyvie, where he despatched some of his troops,

who took possession of the castles of Fyvie and Tollie Barclay, in which

he found a good supply of provisions, which was of great service to his

army. During his stay at Strathbogie, Montrose kept a strict outlook for

the enemy, and scarcely passed a night without scouring the neighbouring

country to the distance of several miles with parties of light foot, who

attacked straggling parties of the Covenanters, and brought in prisoners

from time to time, without sustaining any loss. These petty enterprises,

while they alarmed their enemies, gave an extraordinary degree of

confidence to Montrose’s men, who were ready to undertake any service,

however difficult or dangerous, if he only commanded them to perform it.

When Montrose crossed the

Dee, Argyle was several days’ march behind him. The latter, however,

reached Aberdeen on the 24th of October, and proceeded the following

morning towards Kintore, which he reached the same night. Next morning he

marched forward to Inverury, where he halted at night. Here he was joined

by the Earl of Lothian’s regiment, which increased his force to about

2,500 foot, and 1,200 horse. In his progress through the counties of

Angus, Kincardine, Aberdeen, and Banff, he received no accession of

strength, from the dread which the name and actions of Montrose had

infused into the minds of the inhabitants of these counties.

The sudden movements of

Argyle from Aberdeen to Kintore, and from Kintore to Inverury, form a

remarkable contrast with the slowness of his former motions. He had

followed Montrose through a long and circuitous route, the greater part of

which still bore recent traces of his footsteps, and instead of showing

any disposition to overtake his flying foe, seemed rather inclined to keep

that respectful distance from him so congenial to the mind of one who,

"willing to wound," is "yet still afraid to strike."

But although this questionable policy of Argyle was by no means calculated

to raise his military fame, it had the effect of throwing Montrose, in the

present case, off his guard, and had well-nigh proved fatal to him. The

rapid march of Argyle on Kintore and Inverury, in fact, was effected

without Montrose’s knowledge, for the spies he had employed concealed

the matter from him, and while he imagined that Argyle was still on the

other side of the Grampians, he suddenly appeared within a very few miles

of Montrose’s camp, on the 28th of October.

The unexpected arrival of

Argyle’s army did not disconcert Montrose. His foot, which amounted to

1,500 men, were little more than the half of those under Argyle, while he

had only about 50 horse to oppose 1,200. Yet, with this immense disparity,

he resolved to await the attack of the enemy, judging it inexpedient, from

the want of cavalry, to become the assailant by descending into the plain

where Argyle’s army was encamped. On a rugged eminence behind the castle

of Fyvie, on the uneven sides of which several ditches had been cut and

dikes built to serve as farm fences, Montrose drew up his little but

intrepid host; but before he had marked out the positions to be occupied

by his divisions, he had the misfortune to witness the desertion of a

small body of the Gordons, who had joined him at Strathbogie. They,

however, did not join Argyle, but contented themselves with withdrawing

altogether from the scene of the ensuing action. It is probable that they

came to the determination of retiring, not from cowardice, but from

disinclination to appear in the field against Lord Lewis Gordon, who held

a high command in Argyle’s army. The secession of the Gordons, though in

reality a circumstance of trifling importance in itself, (for had they

remained, they would have fought unwillingly, and consequently might not

have had sufficient resolution to maintain the position which would have

been assigned them,) had a disheartening influence upon the spirits of

Montrose’s men, and accordingly they found themselves unable to resist

the first shock of Argyle’s numerous forces, who, charging them with

great impetuosity, drove them up the eminence, of a considerable part of

which Argyle’s army got possession. In this critical conjuncture, when

terror and despair seemed about to obtain the mastery over hearts to which

fear had hitherto been a stranger, Montrose displayed a coolness and

presence of mind equal to the dangers which surrounded him. Animating them

by his presence, and by the example which he showed in risking his person

in the hottest of the fight, he roused their courage by putting them

further in mind of the victories they had achieved, and how greatly

superior they were in bravery to the enemy opposed to them. After this

emphatic appeal to their feelings, Montrose turned to Colonel O’Kean, a

young Irish gentleman, highly respected by the former for his bravery, and

desired him, with an air of the most perfect sang froid, to go down

with such men as were readiest, and to drive these fellows (meaning Argyle’s

men), out of the ditches, that they might be no more troubled with them. O’Kean

quickly obeyed the mandate, and though the party in the ditches was

greatly superior to the body he led, and was, moreover, supported by some

horse, he drove them away, and captured several bags of powder which they

left behind them in their hurry to escape. This was a valuable

acquisition, as Montrose’s men had spent already almost the whole of

their ammunition.

While O’Kean was

executing this brilliant affair, Montrose observed five troops of horse,

under the Earl of Lothian, preparing to attack his 50 horse, who were

posted a little way up the eminence, with a small wood in their rear. He,

therefore, without a moment’s delay, ordered a party of musketeers to

their aid, who, having interlined themselves with the 50 horse, kept up

such a galling fire upon Lothian’s troopers, that before they had

advanced half way across a field which lay between them and Montrose’s

horse, they were obliged to wheel about and gallop off.

Montrose’s men became so

elated with their success that they could scarcely be restrained from

leaving their ground and making a general attack upon the whole of Argyle’s

army; but although Montrose. did not approve of this design, he disguised

his opinion, and seemed rather to concur in the views of his men, telling

them, however, to be so far mindful of their duty as to wait till he

should see the fit moment for ordering the attack. Argyle remained till

the evening without attempting anything farther, and then retired to a

distance of about three miles across the Spey; his men passed the night

under arms. The only person of note killed in these skirmishes was Captain

Keith, brother of the Earl Marshal.

Next day Argyle resolved to

attack Montrose, with the view of driving him from his position. He was

induced to come to this determination from a report, too well founded,

which had reached him, that Montrose’s army was almost destitute of

ammunition ;—indeed, he had compelled the inhabitants of all the

surrounding districts to deliver up every article of pewter in their

possession for the purpose of being converted into ammunition; but this

precarious supply appears soon to have been exhausted. On arriving at the

bottom of the hill, he changed his resolution, not judging it safe, from

the experience of the preceding day, to hazard an attack. Montrose, on the

other hand, agreeably to his original plan, kept his ground, as he did not

deem it advisable to expose his men to the enemy’s cavalry by descending

from the eminence. With the exception of some trifling skirmishes between

the advanced posts, the main body of both armies remained quiescent during

the whole day. Argyle again retired in the evening to the ground he had

occupied the preceding night, whence he returned the following day, part

of which was spent in the same manner as the former; but long before the

day had expired he led off his army, "upon fair day light," says

Spalding, "to a considerable distance, leaving Montrose to effect his

escape unmolested."

Montrose, thus left to

follow any course he pleased, marched off after nightfall towards

Strathbogie, plundering Turriff and Rothiemay house in his route. He

selected Strathbogie as the place of his retreat on account of the

ruggedness of the country and of the numerous dikes with which it was

intersected, which would prevent the operations of Argyle’s cavalry, and

where he intended to remain till joined by Macdonald, whom he daily

expected from the Highlands with a reinforcement. When Argyle heard of

Montrose’s departure on the following morning, being the last day of

October, he forthwith proceeded after him with his army, thinking to bring

him to action in the open country, and encamped at Tullochbeg on the 2d of

November, where he drew out his army in battle array. He endeavoured to

bring Montrose to a general engagement, and, in order to draw him from a

favourable position he was preparing to occupy, Argyle sent out a

skirmishing party of his Highlanders; but they were soon repulsed, and

Montrose took possession of the ground he had selected.

Baffled in all his attempts

to overcome Montrose by force of arms, Argyle, whose talents were more

fitted for the intrigues of the cabinet than the tactics of the field, had

now recourse to negotiation, with the view of effecting the ruin of his

antagonist. For this purpose he proposed a cessation of arms, and that he

and Montrose should hold a conference, previous to which arrangements

should be entered into for their mutual security. Montrose knew Argyle too

well to place any reliance upon his word, and as he had no doubt that

Argyle would take advantage, during the proposed cessation, to tamper with

his men and endeavour to withdraw them from their allegiance, he called a

council of war, and proposed to retire without delay to the Highlands. The

council at once approved of this suggestion, whereupon Montrose resolved

to march next night as far as Badenoch; and that his army might be able to

accomplish such a long journey within the time fixed, he immediately sent

off all his heavy baggage under a guard, and ordered his men to keep

themselves prepared as if to fight a battle the next day. Scarcely,

however, had the carriages and heavy baggage been despatched, when an

event took place which greatly disconcerted Montrose. This was nothing

less than the desertion of his friend Colonel Sibald and some of his

officers, who went over to the enemy. They were accompanied by Sir William

Forbes of Craigievar, who, having been unable to fulfil the condition on

which he was to obtain his ultimate liberation, had returned two or three

days before to Montrose’s camp.

This distressing occurrence

induced Montrose to postpone his march for a time, as he was quite certain

that the deserters would communicate his plans to Argyle. Ordering,

therefore, back the baggage he had sent off, he resumed his former

position, in which he remained four days, as if he there intended to take

up his winter quarters.

In the meantime Montrose

had the mortification to witness the defection of almost the whole of his

officers, who were very numerous, for, with the exception of the Irish and

Highlanders, they outnumbered the privates from the Lowlands. The bad

example which had been set by Sibbald, the intimate friend of Montrose,

and the insidious promises of preferment held out to them by Argyle,

induced some, whose loyalty was questionable, to adopt this course; but

the idea of the privations to which they would be exposed in traversing,

during winter, among frost and snow, the dreary and dangerous regions of

the Highlands, shook the constancy of others, who, in different

circumstances, would have willingly exposed their lives for their

sovereign. Bad health, inability to undergo the fatigue of long and

constant marches—these and other excuses were made to Montrose as the

reasons for craving a discharge from a service which had now become more

hazardous than ever. Montrose made no remonstrance, but with looks of high

disdain which betrayed the inward workings of a proud and unsubdued mind,

indignant at being thus abandoned at such a dangerous crisis, readily

complied with the request of every man who asked permission to retire. The

Earl of Airly, now sixty years of age and in precarious health, and his

two sons, Sir Thomas and Sir David Ogilvie, out of all the Lowlanders,

alone remained faithful to Montrose, and could, on no account, be

prevailed upon to abandon him. Among others who left Montrose on this

occasion, was Sir Nathaniel Gordon, who, it is said, went over to Argyle’s

camp in consequence of a concerted plan between him and Montrose, for the

purpose of detaching Lewis Gordon from the cause of the Covenanters, a

conjecture which seems to have originated in the subsequent conduct of Sir

Nathaniel and Lord Lewis, who joined Montrose the following year.

Montrose, now abandoned by

all his Lowland friends, prepared for his march, preparatory to which he

sent off his baggage as formerly and after lighting some fires for the

purpose of deceiving the enemy, took his departure on the evening of the

6th of November, and arrived about break of day at Balveny. After

remaining a few days there to refresh his men, he proceeded through

Badenoch, and descended by rapid marches into Athole, where he was joined

by Macdonald and John Muidartach, the captain of the Clanranald, the

latter of whom brought 500 of his men along with him. He was also

reinforced by some small parties from the neighbouring Highlands, whom

Macdonald had induced to follow him.

In the meantime Argyle,

after giving orders to his Highlanders to return home, went himself to

Edinburgh, where he "got but small thanks for his service against

Montrose." Although the Committee of Estates, out of deference,

approved of his conduct, which some of his flatterers considered deserving

of praise because he "had shed no blood;" yet the majority had

formed a very different estimate of his character, during a campaign which

had been fruitful neither of glory nor victory. Confident of success, the

heads of the Covenanters looked upon the first efforts of Montrose in the

light of a desperate and forlorn attempt, rashly and inconsiderately

undertaken, and which they expected would be speedily put down; but the

results of the battles of Tippermuir, Aberdeen, and Fyvie, gave a new

direction to their thoughts, and the royalists, hitherto contemned, began

now to be dreaded and respected. In allusion to the present "posture

of affairs," it is observed by Guthry, that "many who had

formerly been violent, began to talk moderately of business, and what was

most taken notice of, was the lukewarmness of many amongst the ministry,

who now in their preaching had begun to abate much of their former

zeal." The early success of Montrose had indeed caused

some misgivings in the minds of the Covenanters; but as they all hoped

that Argyle would change the tide of war, they showed no disposition to

relax in their seventies towards those who were suspected of favouring the

cause of the king. The signal failure, however, of Argyle’s expedition,

and his return to the capital, quite changed, as we have seen, the aspect

of affairs, and many of those who had been most sanguine in their

calculations regarding the result of the struggle, began now to waver and

to doubt.

While Argyle was passing

his time in Edinburgh, Montrose was meditating a terrible blow at Argyle

himself to revenge the cruelties he had exercised upon the royalists, and

to give confidence to the clans in Argyle’s neighbourhood. These had

been hitherto prevented from joining Montrose’s standard from a dread of

Argyle, who having always a body of 5,000 or 6,000 Highlanders at command,

had kept them in such complete subjection that they dared not, without the

risk of absolute ruin, espouse the cause of their sovereign. The idea of

curbing the power of a haughty and domineering chief whose word was a law

to the inhabitants of an extensive district, ready to obey his cruel

mandates at all times, and the spirit of revenge, the predominating

characteristic of the clans, smoothed the difficulties which presented

themselves in invading a country made almost inaccessible by nature, and

rendered still more unapproachable by the severities of winter. The

determination of Montrose having thus met with a willing response in the

breasts of his men, he lost no time in putting them in motion. Dividing

his army into two parts, he himself marched with the main body, consisting

of the Irish and the Athole-men, to Loch Tay, whence he proceeded through

Breadalbane. The other body, composed of the clan Donald and other

Highlanders, he despatched by a different route, with instructions to meet

him at an assigned spot on the borders of Argyle. The country through

which both divisions passed, being chiefly in possession of Argyle’s

kinsmen or dependants, was laid waste, particularly the lands of Campbell

of Glenorchy.

When Argyle heard of the

ravages committed by Montrose’s army on the lands of his kinsmen, he

hastened home from Edinburgh to his castle at Inverary, and gave orders

for the assembling of his clan, either to repel any attack that might be

made on his own country, or to protect his friends from future aggression.

It is by no means certain that he anticipated an invasion from Montrose,

particularly at such a season of the year, and he seemed to imagine

himself so secure from attack, owing to the intricacy of the passes

leading into Argyle, that although a mere handful of men could have

effectually opposed an army much larger than that of Montrose, he took no

precautions to guard them. So important indeed did he himself consider

these passes to be, that he had frequently declared that he would rather

forfeit a hundred thousand crowns, than that an enemy should know the

passes by which an armed force could penetrate into Argyle.

While thus reposing in

fancied secufity in his impregnable stronghold, and issuing his mandates

for levying his forces, some shepherds arrived in great terror from the

hills, and brought him the alarming intelligence that the enemy, whom he

had imagined were about a hundred miles distant, were within two miles of

his own dwelling. Terrified at the unexpected appearance of Montrose,

whose vengeance he justly dreaded, he had barely self-possession left to

concert measures for his own personal safety, by taking refuge on board a

fishing boat in Loch Fyne, in which he sought his way to the Lowlands,

leaving his people and country exposed to the merciless will of an enemy

thirsting for revenge. The inhabitants of Argyle being thus abandoned by

their chief, made no attempt to oppose Montrose, who, the more effectually

to carry his plan for pillaging and ravaging the country into execution,

divided his army into three parties, under the respective orders of the

captain of clan Ranald, Macdonald, and himself. For upwards of six weeks,

viz., from the 13th of December, 1644, till nearly the end of January

following, these different bodies traversed the whole country without

molestation, burning, wasting, and destroying every thing which came

within their reach. Nor were the people themselves spared, for although it

is mentioned by one writer that Montrose "shed no blood in regard

that all the people (following their lord’s laudable example) delivered

themselves by flight also," it is evident from several contemporary

authors that the slaughter must have been immense. In fact, before the end

of January, the face of a single male inhabitant was not to be seen

throughout the whole extent of Argyle and Lorn, the whole population

having been either driven out of these districts, or taken refuge in dens

and caves known only to themselves.

Having thus retaliated upon

Argyle and his people in a tenfold degree the miseries which he had

occasioned in Lochaber and the adjoining countries, Montrose left Argyle

and Lorn, passing through Glencoe and Lochaber on his way to Lochness. On

his march eastwards he was joined by the laird of Abergeldie, the

Farquharsons of the Braes of Mar, and by a party of the Gordons. The

object of Montrose, by this movement, was to seize Inverness, which was

then protected by only two regiments, in the expectation that its capture

would operate as a stimulus to the northern clans, who had not yet

declared themselves. This resolution was by no means altered on reaching

the head of Lochness, where he learned that the Earl of Seaforth was

advancing to meet him with an army of 5,000 horse and foot, which he

resolved to encounter, it being composed, with the exception of two

regular regiments, of raw and undisciplined levies.

While proceeding, however,

through Abertarf, a person arrived in great haste at Kilcummin, the

present fort Augustus, who brought him the surprising intelligence that

Argyle had entered Lochaber with an army of 3,000 men; that he was burning

and laying waste the country, and that his head-quarters were at the old

castle of Inverlochy. After Argyle had effected his escape from Inverary,

he had gone to Dumbarton, where he remained till Montrose’s departure

from his territory. While there, a body of covenanting troops who had

served in England, arrived under the command of Major-general Baillie, for

the purpose of assisting Argyle in expelling Montrose from his bounds; but

on learning that Montrose had left Argyle, and was marching through

Glencoe and Lochaber, General Baillie determined to lead his army in an

easterly direction through the Lowlands, with the intention of

intercepting Montrose, should he attempt a descent. At the same time it

was arranged between Baillie and Argyle that the latter, who had now

recovered from his panic in consequence of Montrose’s departure, should

return to Argyle and collect his men from their hiding-places and

retreats. As it was not improbable, however, that Montrose might renew his

visit, the Committee of Estates allowed Baillie to place 1,100 of his

soldiers at the disposal of Argyle, who, as soon as he was able to muster

his men, was to follow Montrose’s rear, yet so as to avoid an

engagement, till Baillie, who, on hearing of Argyle’s advance into

Lochaber, was to march suddenly across the Grampians, should attack

Montrose in front. To assist him in levying and organizing his clan,

Argyle called over Campbell of Auchinbreck, his kinsman, from Ireland, who

had considerable reputation as a military commander. In terms of his

instructions, therefore, Argyle had entered Lochaber, and had advanced as

far as Inverlochy, when, as we have seen, the news of his arrival was

brought to Montrose.

Montrose was at first

almost disinclined, from the well-known reputation of Argyle, to credit

this intelligence, but being fully assured of its correctness from the

apparent sincerity of his informer, he lost not a moment in making up his

mind as to the course he should pursue. He might have instantly marched

back upon Argyle by the route he had just followed; but as the latter

would thus get due notice of his approach, and prepare himself for the

threatened danger, Montrose resolved upon a different plan. The design he

conceived could only have originated in the mind of such a bold and

enterprising commander as Montrose, before whose daring genius

difficulties hitherto deemed insurmountable at once disappeared. The idea

of carrying an army over dangerous and precipitous mountains, whose wild

and frowning aspect seemed to forbid the approach of human footsteps, and

in the middle of winter, too, when the formidable perils of the journey

were greatly increased by the snow, however chimerical it might have

seemed to other men, appeared quite practicable to Montrose, whose

sanguine anticipations of the advantages to be derived from such an

extraordinary exploit, more than counterbalanced, in his mind, the risks

to be encountered.

The distance between the

place where Montrose received the news of Argyle’s arrival and

Inverlochy is about thirty miles; but this distance was considerably

increased by the devious track which Montrose followed. Marching along the

small river Tarf in a southerly direction, he crossed the hills of Lairie

Thierard, passed through Glenroy, and after traversing the range of

mountains between the Glen and Ben Nevis, he arrived in Glennevis before

Argyle had the least notice of his approach. Before setting out on his

march, Montrose had taken the wise precaution of placing guards upon the

common road leading to Inverlochy, to prevent intelligence of his

movements being carried to Argyle, and he had killed such of Argyle’s

scouts as he had fallen in with in the course of his march. This

fatiguing. and unexampled journey had been performed in little more than a

night and a day, and when in the course of the evening, Montrose’s men

arrived in Glennevis, they found themselves so weary and exhausted that

they could not venture to attack the enemy. They therefore lay under arms

all night, and refreshed themselves as they best could till next morning.

As the night was uncommonly clear, it being moonlight, the advanced posts

of both armies kept up a small fire of musketry, which led to no result.

In the meantime Argyle,

after committing his army to the charge of his cousin, Campbell of

Auchinbreck, with his customary prudence, went, during the night, on board

a boat in the loch, excusing himself for this apparent pusillanimous act

by alleging his incapacity to enter the field of battle in consequence of

some contusions he had received by a fall two or three weeks before; but

his enemies averred that cowardice was the real motive which induced him

to take refuge in his galley, from which he witnessed the defeat and

destruction of his army. This somewhat suspicious action of Argyle—and

it was not the only time he provided for his personal safety in a similar

manner—is accounted for in the following (? ironical) way by the author

of Britane’s Distemper (p. 100):-

"In this confusion,

the commanders of there armie lightes wpon this resolution, not to hazart

the marquisse owne persone; for it seems not possible that Ardgylle

himselfe, being a nobleman of such eminent qualitie, a man of so deepe and

profund judgement, one that knew so weell what belongeth to the office of

a generall, that any basso motion of feare, I say, could make him so

wnsensible of the poynt of honour as is generally reported. Nether will I,

for my owne pairt, belieue it; but I am confident that those barrones of

his kinred, wha ware captanes and commanderes of the armie, feareing the

euent of this battelle, for diuers reasones; and one was, that Allan M’Collduie,

ane old fox, and who was thought to be a seer, had told them that there

should be a battell lost there by them that came first to seiko battell;

this was one cause of there importunitie with him that he should not come

to battell that day; for they sawe that of necessitie they most feght, and

would not hazart there cheife persone, urgeing him by force to reteire to

his galay, which lay hard by, and committe the tryall of the day to them;

he, it is to be thought, with great difficultie yeelding to there request,

leaues his cusine, the laird of Auchinbreike, a most walorous and brane

gentleman, to the generall commande of the armie, and takes with himselfe

only sir James Rollocke, his brother in lawe, sir Jhone Wachope of Nithrie,

Mr. Mungo Law, a preacher. It is reported those two last was send from

Edinburgh with him to beam witnesse of the expulsion of those rebelles,

for so they ware still pleased to terme the Royalistes."

It would appear that it was

not until the morning of the battle that Argyle’s men were aware that it

was the army of Montrose that was so near them, as they considered it

quite impossible that he should have been able to bring his forces across

the mountains; they imagined that the body before them consisted of some

of the inhabitants of the country, who had collected to defend their

properties. But they were undeceived when, in the dawn of the morning, the

warlike sound of Montrose’s trumpets, resounding through the glen where

they lay, and reverberating from the adjoining hills, broke upon their

ears. This served as the signal to both armies to prepare for battle.

Montrose drew out his army in an extended line. The right wing consisted

of a regiment of Irish, under the command of Macdonald, his major-general;

the centre was composed of the Athole-men, the Stuarts of Appin, the

Macdonalds of Glencoe, and other Highlanders, severally under the command

of Clanranald, M’Lean, and Glengary; and the left wing consisted of some

Irish, at the head of whom was the brave Colonel O’Kean. A body of Irish

was placed behind the main body as a reserve, under the command of Colonel

James M’Donald, alias O’Neill. The general of Argyle’s army formed

it in a similar manner. The Lowland forces were equally divided, and

formed the wings, between which the Highlanders were placed. Upon a rising

ground, behind this line, General Campbell drew up a reserve of

Highlanders, and placed a field-piece. Within the house of Inverlochy,

which was only about a pistol-shot from the place where the army was

formed, he planted a body of 40 or 50 men to protect the place, and to

annoy Montrose’s men with discharges of musketry. The account

given by Gordon of Sallagh, that Argyle had transported the half of his

army over the water at Inverlochy, under the command of Auchinbreck, and

that Montrose defeated this division, while Argyle was prevented from

relieving it with the other division, from the intervening of "an arm

of the sea, that was interjected betwixt them and him," is probably

erroneous, for the circumstance is not mentioned by any other writer of

the period, and it is well known, that Argyle abandoned his army, and

witnessed its destruction from his galley, — circumstances which Gordon

altogether overlooks.

It was at sunrise, on

Sunday, the 2d of February, 1645, that Montrose, after having formed his

army in battle array, gave orders to his men to advance upon the enemy.

The left wing of Montrose’s army, under the command of O’Kean, was the

first to commence the attack, by charging the enemy’s right. This was

immediately followed by a furious assault upon the centre and left wing of

Argyle’s army, by Montrose’s right wing and centre. Argyle’s right

wing not being able to resist the attack of Montrose’s left, turned

about and fled, which circumstance had such a discouraging effect on the

remainder of Argyle’s troops, that after discharging their muskets, the

whole of them, including the reserve, took to their heels.

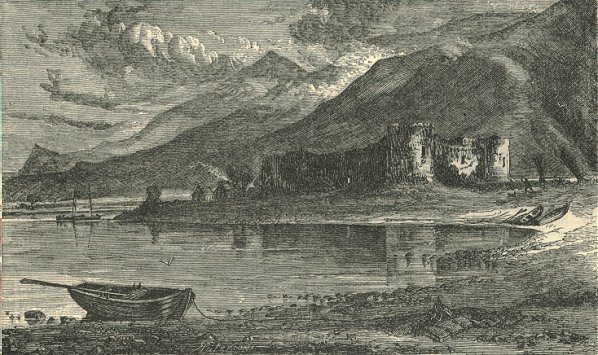

Inverlochy Castle - From M'Culloch's celebrated picture in the Edinburgh

National Gallery

The rout now became

general. An attempt was made by a body of about 200 of the fugitives, to

throw themselves into the castle of Inverlochy, but a party of Montrose’s

horse prevented them. Some of the flying enemy directed their course along

the side of Loch Eil, but all these were either killed or drowned in the

pursuit. The greater part, however, fled towards the hills in the

direction of Argyle, and were pursued by Montrose’s men, to the distance

of about eight miles. As no resistance was made by the defeated party in

their flight, the carnage was very great, being reckoned at 1,500 men.

Many more would have been cut off had it not been for the humanity of

Montrose, who did every thing in his power to save the unresisting enemy

from the fury of his men, who were not disposed to give quarter to the

unfortunate Campbells. Having taken the castle, Montrose not only treated

the officers, who were from the Lowlands, with kindness, but gave them

their liberty on parole.

Among the principal persons

who fell on Argyle’s side, were the commander, Campbell of Auchinbreck,

Campbell of Lochnell, the eldest son of Lochnell, and his brother, Cohn; M’Dougall

of Rara and his eldest son; Major Menzies, brother to the laird, (or Prior

as he was called) of Achattens Parbreck; and the provost of the church of

Kilmun. The loss on the side of Montrose was extremely trifling. The

number of wounded is indeed not stated, but he had only three privates

killed. He sustained, however, a severe loss in Sir Thomas Ogilvie, son of

the Earl of Airly, who died a few days after the battle, of a wound he

received in the thigh. Montrose regretted the death of this steadfast

friend and worthy man, with feelings of real sorrow, and caused his body

to be interred in Athole with due solemnity. Montrose immediately after

the battle sent a messenger to the king with a letter, giving an account

of it, at the conclusion of which he exultingly says to Charles,

"Give me leave, after I have reduced this country, and conquered from

Dan to Beersheba, to say to your Majesty, as David’s general to his

master, Come thou thyself, lest this country be called by my name."

When the king received this letter, the royal and parliamentary

commissioners were sitting at Uxbridge negotiating the terms of a peace;

but Charles, induced by the letter, imprudently broke off the negotiation,

a circumstance which led to his ruin. |