|

WHEN the disastrous news of

the battle of lnverlochy reached Edinburgh, the Estates were thrown into a

state of great alarm. They had, no doubt, begun to fear, before that

event, and, of course, to respect the prowess of Montrose, but they never

could have been made to believe that, within the space of a few days, a

well-appointed army, composed in part of veteran troops, would have been

utterly defeated by a force so vastly inferior in point of numbers, and

beset with difficulties and dangers to which the army of Argyle was not

exposed. Nor were the fears of the Estates much allayed by the appearance

of Argyle, who arrived at Edinburgh to give them an account of the affair,

"having his left arm tied up in a scarf, as if he had been at

bones-breaking." It is true that Lord Balmerino made a speech before

the assembly of the Estates, in which he affirmed, that the great loss

reported to be sustained at Inverlochy "was but the invention of the

malignants, who spake as they wished," and that "upon his honour,

not more than thirty of Argyle’s men had been killed;" but as the

disaster was well known, this device only misled the weak and ignorant.

Had Montrose at this juncture descended into the Lowlands, it is not

improbable that his presence might have given a favourable turn to the

state of matters in the south, where the king’s affairs were in the most

precarious situation; but such a design does not seem to have accorded

with his views of prolonging the contest in the Highlands, which were more

suitable than the Lowlands to his plan of operations, and to the nature of

his forces.

Accordingly, after allowing

his men to refresh themselves a few days at Inverlochy, Montrose returned

across the mountains of Lochaber into Badenoch, "with displayed

banner." Marching down the south side of the Spey, he crossed that

river at Balchastel, and entered Moray without opposition. He proceeded by

rapid strides towards the town of Inverness, which he intended to take

possession of; but, on arriving in the neighbourhood, he found it

garrisoned by the Iaird of Lawers’ and Buchanan’s regiments. As he did

not wish to consume his time in a siege, he immediately altered his course

and marched in the direction of Elgin, issuing, as he went along, a

proclamation in the king’s name, calling upon all males, from 16 to 60

years of age, to join him immediately, armed as they best could, on foot

or on horse, and that under pain of fire and sword, as rebels to the king.

In consequence of this threat Montrose was joined by some of the

Moray-men, including the laird of Grant and 200 of his followers; and, to

show an example of severity, he plundered the houses and laid waste the

estates of many of the principal gentlemen of the district, carrying off,

at the same time, a large quantity of cattle and effects, and destroying

the boats and nets which they fell in with on the Spey.

Whilst Montrose was thus

laying waste part of Moray, a committee of the Estates, consisting of the

Earl of Seaforth, the laird of Tunes, Sir Robert Gordon, the laird of

Pluscardine, and others, was sitting at Elgin; these, on hearing of his

proceedings, prohibited the holding of the fair which was kept there

annually on Fasten’s eve, and to which many merchants and others in the

north resorted, lest the property brought there for sale might fall a prey

to Montrose’s army. They, at the same time, sent Sir Robert Gordon,

Mackenzie of Pluscardine, and Innes of Luthers, to treat with Montrose, in

name of the gentry of Moray, most of whom were then assembled in Elgin;

but he refused to enter into any negotiation, offering, at the same time,

to accept of the services of such as would join him and obey him as the

king’s lieutenant. Before this answer had been communicated to the

gentry at Elgin, they had all fled from the town in consequence of hearing

that Montrose was advancing upon them with rapidity. The laird of Innes,

along with some of his friends, retired to the castle of Spynie, possessed

by his eldest son, which was well fortified and provided with every

necessary for undergoing a siege. The laird of Duffus went into

Sutherland. As soon as the inhabitants of the town saw the committee

preparing to leave it, most of them also resolved to depart, which they

did, carrying along with them their principal effects. Some went to

Inverness, and others into Ross, but the greater part went to the castle

of Spynie, where they sought and obtained refuge.

Apprehensive that Montrose

might follow up the dreadful example he had shown, by burning the town, a

proposal was made to, and accepted by him, to pay four thousand merks to

save the town from destruction; but, on entering it, which he did on the

19th of February, his men, and particularly the laird of Grant’s party,

were so disappointed in their hopes of plunder, in consequence of the

inhabitants having carried away the best of their effects, that they

destroyed every article of furniture which was left.

Montrose was joined, on his

arrival at Elgin, by Lord Gordon, the eldest son of the Marquis of Huntly,

with some of his friends and vassals. This young nobleman had been long

kept in a state of durance by Argyle, his uncle, contrary to his own

wishes, and now, when an opportunity had for the first time occurred, he

showed the bent of his inclination by declaring for the king.

On taking possession of

Elgin, Montrose gave orders to bring all the ferry-boats on the Spey to

the north side of the river, and he stationed sentinels at all the fords

up and down, to watch any movements which might be made by the enemies’

forces in the south.

Montrose, thereupon, held a

council of war, at which it was determined to cross the Spey, march into

the counties of Banff and Aberdeen, by the aid of Lord Gordon, raise the

friends and retainers of the Marquis of Huntly, and thence proceed into

the Mearns, where another accession of forces was expected. Accordingly,

Montrose left Elgin on the 4th of March with the main body of his army,

towards the Bog of Gicht, accompanied by the Earl of Seaforth, Sir Robert

Gordon, the lairds of Grant, Pluscardine, Findrassie, and several other

gentlemen who "had come in to him" at Elgin. To punish the Earl

of Findlater, who had refused to join him, Montrose sent the Farquharsons

of Braemar before him, across the Spey, who plundered, without mercy, the

town of Cohen, belonging to the earl.

After crossing the Spey,

Montrose, either apprehensive that depredations would be committed upon

the properties of his Moray friends who accompanied him, by the two

regiments which garrisoned Inverness, and the Covenanters of that

district, or having received notice to that effect, he allowed the Earl of

Seaforth, the laird of Grant, and the other Moray gentlemen, to return

home to defend their estates; but before allowing them to depart, he made

them take a solemn oath of allegiance to the king, and promise that they

should never henceforth take up arms against his majesty or his loyal

subjects. At the same time, he made them come under an engagement to join

him with all their forces as soon as they could do so. The Earl of

Seaforth, however, disregarded his oath, and again joined the ranks of the

Covenanters. In a letter which he wrote to the committee of Estates at

Aberdeen, he stated that he had yielded to Montrose through fear only, and

he avowed that he would abide by "the good cause to his death."

On Montrose’s arrival at

Strathbogie, or Gordon castle, Lord Graham, his eldest son, a most

promising youth of sixteen, became unwell, and died after a few days’

illness. The loss of a son who had followed him in his campaigns, and

shared with him the dangers of the field, was a subject of deep regret to

Montrose. While Montrose was occupied at the death-bed of his son, Lord

Gordon was busily employed among the Gordons, out of whom he speedily

raised a force of about 500 foot, and 160 horse.

With this accession to his

forces, Montrose left Strathbogie and marched towards Banff, on his route

to the south. In passing by the house of Cullen, in Boyne, the seat of the

Earl of Findlater, who had fled to Edinburgh, and left the charge of the

house to the countess, a party of Montrose’s men entered the house,

which they plundered of all its valuable contents. They then proceeded to

set the house on fire, but the countess entreated Montrose to order his

men to desist, and promised that if her husband did not come to Montrose

and give him satisfaction within fifteen days, she would pay him 20,000

merks, of which sum she instantly paid down 5,000. Montrose complied with

her request, and also spared the lands, although the earl was "a

great Covenanter." Montrose’s men next laid waste the lands in the

Boyne, burnt the houses, and plundered the minister of the place of all

his goods and effects, including his books. The laird of Boyne shut

himself up in his stronghold, the Crag, where he was out of danger; but he

had the misfortune to see his lands laid waste and destroyed. Montrose

then went to Banff, which he gave up to indiscriminate plunder. His troops

did not leave a vestige of moveable property in the town, and they even

stripped to the skin every man they met with in the streets. They also

burned two or three houses of little value, but not a drop of blood was

shed.

From Banff Montrose

proceeded to Turriff, where a deputation from the town council of Aberdeen

waited upon him, to represent the many miseries which the loyal city had

suffered from its frequent occupation by hostile armies since the first

outbreaking of the unfortunate troubles which molested the kingdom.

They further represented,

that such was the terror of the inhabitants at the idea of another visit

from his Irish troops, that all the men and women, on hearing of his

approach, had made preparations for abandoning the town, and that they

would certainly leave it if they did not get an assurance from the marquis

of safety and protection. Montrose heard the commissioners patiently,

expressed his regret at the calamities which had befallen their town, and

bade them not be afraid, as he would take care that none of his foot, or

Irish, soldiers should come within eight miles of Aberdeen; and that if he

himself should enter the town, he would support himself at his own

expense. The commissioners returned to Aberdeen, and related the

successful issue of their journey, to the great joy of all the

inhabitants.

Whilst Montrose lay at

Turriff, Sir Nathaniel Gordon, with some troopers, went to Aberdeen, which

he entered on Sunday, the 9th of March, on which day there had been

"no sermon in either of the Aberdeens," as the ministers had

fled the town. The keys of the churches, gates, and jail were delivered to

him by the magistrates. The following morning Sir Nathaniel was joined by

100 Irish dragoons. After releasing some prisoners, he went to Torry, and

took, after a slight resistance, 1,800 muskets, pikes, and other arms,

which had been left in charge of a troop of horse. Besides receiving

orders to watch the town, Sir Nathaniel was instructed to send out scouts

as far as Cone to watch the enemy, who were daily expected from the south.

When reconnoitering, a skirmish took place at the bridge of Dee, in which

Captain Keith’s troop was routed. Finding the country quite clear, and

no appearance of the covenanting forces, Gordon returned back to the army,

which had advanced to Frendraught. No attempt was made upon the house of

Frendraught, which was kept by the young viscount in absence of his

father, who was then at Muchallis with his godson, Lord Fraser; but

Montrose destroyed 60 ploughs of land belonging to Frendraught within the

parishes of Forgue, Inverkeithnie, and Drumblade, and the house of the

minister of Forgue, with all the other houses, and buildings, and their

contents. Nothing, in fact, was spared. All the cattle, horses, sheep, and

other domestic animals, were carried off, and the whole of Frendraught’s

lands were left a dreary and uninhabitable waste.

From Pennyburn, Montrose

despatched, on the 10th of March, a letter to the authorities of Aberdeen,

commanding them to issue an order that all men, of whatever description,

between the age of sixteen and sixty, should meet him equipped in their

best arms, and such of them as had horses, mounted on the best of them, on

the 15th of March, at his camp at Inverury, under the pain of fire and

sword. In consequence of this mandate he was joined by a considerable

number of horse and foot. On the 12th of March, Montrose arrived at

Kintore, and took up his own quarters in the house of John Cheyne, the

minister of the place, whence he issued an order commanding each parish

within the presbytery of Aberdeen, (with the exception of the town of

Aberdeen,) to send to him two commissioners, who were required to bring

along with them a complete roll of the whole heritors, feuars, and

liferenters of each parish. His object, in requiring such a list, was to

ascertain the number of men capable of serving, and also the names of

those who should refuse to join him. Commissioners were accordingly sent

from the parishes, and the consequence was, that Montrose was joined daily

by many men who would not otherwise have assisted him, but who were now

alarmed for the safety of their properties. While at Kintore, an

occurrence took place which vexed Montrose exceedingly.

To reconnoitre and watch

the motions of the enemy, Montrose had, on the 12th of March, sent Sir

Nathaniel Gordon, along with Donald Farquharson, Captain Mortimer, and

other well-mounted cavaliers, to the number of about 80, to Aberdeen. This

party, perceiving no enemy in the neighbourhood of Aberdeen, utterly

neglected to place any sentinels at the gates of the town, and spent their

time at their lodgings in entertainments and amusements. This careless

conduct did not pass unobserved by some of the Covenanters in the town,

who, it is said, sent notice thereof to Major-general Hurry, the second in

command under General Baillie, who was then lying at the North Water

Bridge with Lord Balcarras’s and other foot regiments. On receiving this

intelligence, Hurry put himself at the head of 160 horse and foot, taken

from the regular regiments, and some troopers and musketeers, and rode off

to Aberdeen in great haste, where he arrived on the 15th of March, at 8 o’clock

in the evening. Having posted sentinels at the gates to prevent any of

Montrose’s party from escaping, he entered the town at an hour when they

were all carelessly enjoying themselves in their lodgings, quite

unapprehensive of such a visit. The noise in the streets, occasioned by

the tramping of the horses, was the first indication they had of the

presence of the enemy, but it was then too late for them to defend

themselves. Donald Farquharson was killed in the street, opposite the

guard-house; "a brave gentleman," says Spalding, "and one

of the noblest captains amongst all the Highlanders of Scotland, and the

king’s man for life and death." The enemy stripped him of a rich

dress he had put on the same day, and left his body lying naked in the

street. A few other gentlemen were killed, and some taken prisoners, but

the greater part escaped. Hurry left the town next day, and, on his return

to Baillie’s camp, entered the town of Montrose, and carried off Lord

Graham, Montrose’s second son, a boy of fourteen years of age, then at

school, who, along with his teacher, was sent to Edinburgh, and committed

to the castle.

The gentlemen who had

escaped from Aberdeen returned to Montrose, who was greatly offended at

them for their carelessness. The magistrates of Aberdeen, alarmed lest

Montrose should inflict summary vengeance upon the town, as being

implicated in the attack upon the cavaliers, sent two commissioners to

Kintore to assure him that they were in no way concerned in that affair.

Although he heard them with great patience, he gave them no satisfaction

as to his intentions, and they returned to Aberdeen without being able to

obtain any promise from him to spare the town. Montrose contented himself

with making the merchants furnish him with cloth, and gold and silverlace,

to the amount of £10,000 Scots, for the use of his army, which he held

the magistrates bound to pay, by a tax upon the inhabitants.

"Thus," says Spalding, "cross upon cross upon

Aberdeen."

When Sir Nathaniel Gordon

and the remainder of his party returned to Kintore, Montrose despatched,

on the same day (March 16th), a body of 1,000 horse and foot, the latter

consisting of Irish, to Aberdeen, under the command of Macdonald, his

major-general. Many of the inhabitants, alarmed at the approach of this

party, and still having the fear of the Irish before their eyes, were

preparing to leave the town; but Macdonald relieved their apprehensions by

assuring them that the Irish, who amounted to 700, should not enter the

town; he accordingly stationed them at the Bridge of Dee and the Two Mile

Cross, he and his troopers alone entering the town. With the exception of

the houses of one or two "remarkable Covenanters," which were

plundered, Macdonald showed the utmost respect for private property, a

circumstance which obtained for him the esteem of the inhabitants, who had

seldom experienced such kind treatment before.

Having discharged the last

duties to the brave Farquharson and his companions, Macdonald left

Aberdeen, on March 18th, to join Montrose at Durris; but he had not

proceeded far when complaints were brought to him that some of his Irish

troops, who had lagged behind, had entered the town, and were plundering

it. Macdonald, therefore, returned immediately to the town, and drove,

says Spalding, "all these rascals with sore skins out of the town

before him."

Before leaving Kintore, the

Earl of Airly was attacked by a fever, in consequence of which, Montrose

sent him to Lethintie, the residence of the earl’s son-in-law, under a

guard of 300 men; but he was afterwards removed to Strathbogie for greater

security. On arriving, March 17th, at Durris, in Kincardineshire, where he

was joined by Macdonald, Montrose burnt the house and offices to the

ground, set fire to the grain, and swept away all the cattle, horses, and

sheep. He also wasted such of the lands of Fintry as belonged to Forbes of

Craigievar, to punish him for the breach of his parole; treating in the

same way the house and grain belonging to Abercrombie, the minister of

Fintry, who was "a main Covenanter." On the 19th, Montrose

entered Stonehaven, and took up his residence in the house of James Clerk,

the provost of the town. Here learning that the Covenanters in the north

were troubling Lord Gordon’s lands, he despatched 500 of Gordon’s foot

to defend Strathbogie and his other possessions; but he still retained

Lord Gordon himself with his troopers.

On the day after his

arrival at Stonehaven, Montrose wrote a letter to the Earl Marshal, who,

along with sixteen ministers, and some other persons of distinction, had

shut himself up in his castle of Dunottar. The bearer of the letter was

not, however, suffered to enter within the gate, and was sent back, at the

instigation probably of the earl’s lady and the ministers who were with

him, without an answer. Montrose then endeavoured, by means of George

Keith, the Earl Marshal’s brother, to persuade the latter to declare for

the king, but he refused, in consequence of which Montrose resolved to

inflict summary vengeance upon him, by burning and laying waste his lands

and those of his retainers in the neighbourhood. Acting upon this

determination, he, on the 21st of March, set fire to the houses adjoining

the castle of Dunottar, and burnt the grain which was stacked in the

barn-yards. Even the house of the minister did not escape. He next set

fire to the town of Stonehaven, sparing only the house of the provost, in

which he resided; plundered a ship which lay in the harbour, and then set

her on fire, along with all the fishing boats. The lands and houses of

Cowic shared the same hard fate. Whilst the work of destruction was going

on, it is said that the inhabitants appeared before the castle of Dunottar,

and, setting up cries of pity, implored the earl to save them from ruin,

but they received no answer to their supplications, and the earl witnessed

from his stronghold the total destruction of the properties of his tenants

and dependents without making any effort to stop it. After he had effected

the destruction of the barony of Dunottar, Montrose set fire to the lands

of Fetteresso, one-fourth part of which was burnt up, together with the

whole corn in the yards. A beautiful deer park was also burnt, and its

alarmed inmates were all taken and killed, as well as all the cattle in

the barony. Montrose next proceeded to Drumlithie and Uric, belonging to

John Forbes of Leslie, a leading Covenanter, where he committed similar

depredations.

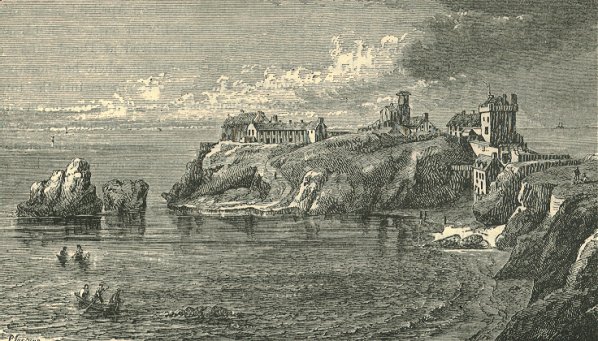

Dunnottar Castle in the 17th century - From Slezer's

Theatrum Scotia (1693)

Montrose, on the following

day, advanced to Fettercairn, where he quartered his foot soldiers,

sending out quarter-masters through the country, and about the town of

Montrose, to provide quarters for some troopers; but, as these troopers

were proceeding on their journey, they were alarmed by the sudden

appearance of some of Major-general Hurry’s troops, who had concealed

themselves within the plantation of Halkerton. These, suddenly issuing

from the wood, set up a loud shout, on hearing which the troopers

immediately turned to the right about and went back to the camp. This

party turned out to be a body of 600 horse, under the command of Hurry

himself, who had left the head-quarters of General Baillie, at Brechin,

for the purpose of reconnoitering Montrose’s movements. In order to

deceive Hurry, who kept advancing with his 600 horse, Montrose placed his

horse, which amounted only to 200, and which he took care to line with

some expert musqueteers, in a prominent situation, and concealed his foot

in an adjoining valley. This ruse had the desired effect, for Hurry

imagining that there were no other forces at hand, immediately attacked

the small body of horse opposed to him; but he was soon Un-deceived by the

sudden appearance of the foot, and forced to retreat with precipitation.

Though his men were greatly alarmed, Hurry, who was a brave officer,

having placed himself in the rear, managed to retreat across the North Esk

with very little loss.

After this affair Montrose

allowed his men to refresh themselves for a few days, and, on the 25th of

March, put his army in motion in the direction of Brechin. On hearing of

his approach, the inhabitants of the town concealed their effects in the

castle, and in the steeples of churches, and fled. Montrose’s troops,

although they found out the secreted goods, were so enraged at the conduct

of the inhabitants that they plundered the town, and burnt about sixty

houses.

From Brechin, Montrose

proceeded through Angus, with the intention either of fighting Ballie, or

of marching onwards to the south. His whole force, at this time, did not

exceed 3,000 men, and, on reaching Kirriemuir, his cavalry was greatly

diminished by his having been obliged to send away about 160 horsemen to

Strathbogie, under Lord Gordon and his brother Lewis, to defend their

father’s possessions against the Covenanters. Montrose proceeded with

his army along the foot of the Grampians, in the direction of Dunkeld,

where he intended to cross the Tay in the sight of General Baillie, who

commanded an army greatly superior in numbers; but, although Montrose

frequently offered him battle, Baillie, contrary, it is said, to the

advice of Hurry, as often declined it. On arriving at the water of Isle,

the two armies, separated by that stream, remained motionless for several

days, as if undetermined how to act. At length Montrose sent a trumpeter

to Baillie offering him battle; and as the water could not be safely

passed by his army if opposed, Montrose proposed to allow Baillie to pass

it unmolested, on condition that he would give him his word of honour that

he would fight without delay; but Baillie answered that he would attend to

his own business himself, and that he would fight when he himself thought

proper. The conduct of Baillie throughout seems altogether extraordinary,

but it is alleged that he had no power to act for himself, being subject

to the directions of a council of war, composed of the Earls of Crawford

and Cassilis, Lords Balmerino, Kirkcudbright, and others.

As Montrose could not

attempt to cross the water of Isla without cavalry, in opposition to a

force so greatly superior, he led his army off in the direction of the

Grampians, and marched upon Dunkeld, of which he took possession. Baillie

being fully aware of his intention to cross the Tay, immediately withdrew

to Perth for the purpose of opposing Montrose’s passage; but, if

Montrose really entertained such an intention after he had sent away the

Gordon troopers, he abandoned it after reaching Dunkeld, and resolved to

retrace his steps northwards. Being anxious, however, to signalize himself

by some important achievement before he returned to the north, and to give

confidence to the royalists, he determined to surprise Dundee, a town

which had rendered itself particularly obnoxious to him for the resistance

made by the inhabitants after the battle of Tippermuir. Having sent off

the weaker part of his troops, and those who were lightly armed, with his

heavy baggage, along the bottom of the hills with instructions to meet him

at Brechin, Montrose himself, at the head of about 150 horse, and 600

expert musketeers, left Dunkeld on April 3d about midnight, and

marched with such extraordinary expedition that he arrived at Dundee Law

at 10 o’clock in the morning, where he encamped. Montrose then sent a

trumpeter into the town with a summons requiring a surrender, promising

that, in the event of compliance, he would protect the lives and

properties of the inhabitants, but threatening, in case of refusal, to set

fire to the town and put the inhabitants to the sword. Instead of

returning an answer to this demand, the town’s people put the messenger

into prison. This insult was keenly felt by Montrose, who immediately gave

orders to his troops to storm the town in three different places at once,

and to fulfil the threat which he had held out in case of resistance. The

inhabitants, in the mean time, made such preparations for defence as the

shortness of the time allowed, but, although they fought bravely, they

could not resist the impetuosity of Montrose’s troops, who, impelled by

a spirit of. revenge, and a thirst for plunder, which Dundee, then one of

the largest and most opulent towns in Scotland, offered them considerable

opportunities of gratifying, forced the inhabitants from the stations they

occupied, and turned the cannon which they had planted in the streets

against themselves. The contest however, continued in various quarters of

the town for several hours, during which the town was set on fire in

different places. The whole of that quarter of the town called the Bonnet

Hill fell a prey to the flames, and the entire town would have certainly

shared the same fate had not Montrose’s men chiefly occupied themselves

in plundering the houses and filling themselves with the contents of the

wine cellars. The sack of the town continued till the evening, and the

inhabitants were subjected to every excess which an infuriated and

victorious soldiery, maddened by intoxication, could inflict.

This melancholy state of

things was, however, fortunately put an end to by intelligence having been

brought to Montrose, who had viewed the storming of the town from the

neighbouring height of Dundee Law, that General Baillie was marching in

great haste down the Carse of Gowrie, towards Dundee, with 3,000 foot and

800 horse. On receiving this news from his scouts, Montrose gave immediate

orders to his troops to evacuate Dundee, but so intent were they upon

their booty, that it was with the utmost difficulty they could be

prevailed upon to leave the town, and, before the last of them could be

induced to retire, some of the enemy’s troops were within gun-shot of

them. The sudden appearance of Baillie’s army was quite unlooked-for, as

Montrose had been made to believe, from the reports of his scouts, that it

had crossed the Tay, and was proceeding to the Forth, when, in fact, only

a very small part, which had been mistaken by the scouts for the entire

army of Baillie, had passed.

In this critical

conjuncture, Montrose held a council of war, to consult how to act under

the perilous circumstances in which he was now placed. The council was

divided between two opinions. Some of them advised Montrose to consult his

personal safety, by riding off to the north with his horse, leaving the

foot to their fate, as they considered it utterly impossible for him to

carry them off in their present state, fatigued, and worn out as they were

by a march of 24 miles during the preceding night, and rendered almost

incapable of resisting the enemy, from the debauch they had indulged in

during the day. Besides, they would require to march 20 or even 30 miles,

before they could reckon themselves secure from the attacks of their

pursuers, a journey which it was deemed impossible to perform, without

being previously allowed some hours repose. In this way, and in no other,

urged the advocates of this view, might he expect to retrieve matters, as

he could, by his presence among his friends in the north, raise new

forces; but that, if he himself was cut off, the king’s affairs would be

utterly ruined. The other part of the council gave quite an opposite

opinion, by declaring that, as the cause for which they had fought so

gloriously was now irretrievably lost, they should remain in their

position, and await the issue of an attack, judging it more honourable to

die fighting in defence of their king, than to seek safety in an

ignominious flight, which would be rendered still more disgraceful by

abandoning their unfortunate fellow-warriors to the mercy of a revengeful

foe.

Montrose, however,

disapproved of both these plans. He considered the first as unbecoming the

generosity of men who had fought so often side by side; and the second he

thought extremely rash and imprudent. He, therefore, resolved to steer a

middle course, and, refusing to abandon his brave companions in arms in

the hour of danger, gave orders for an immediate retreat, in the direction

of Arbroath. This, however, was a mere manoeuvre to deceive the enemy, as

Montrose intended, after nightfall, to march towards the Grampians. In

order to make his retreat more secure, Montrose despatched 400 of his

foot, and gave them orders, to march as quickly as possible, without

breaking their ranks. These were followed by 200 of his most expert

musketeers, and Montrose himself closed the rear with his horse in open

rank, so as to admit the musketeers to interline them, in case of an

attack. It was about six o’clock in the evening when Montrose began his

retreat, at which hour the last of Baillie’s foot had reached Dundee.

Scarcely had Montrose begun

to move, when intelligence was received by Baillie, from some prisoners he

had taken, of Montrose’s intentions, which was now confirmed by ocular

proof. A proposal, it is said, was then made by Hurry, to follow Montrose

with the whole army, and attack him, but Baillie rejected it; and the

better, as he thought, to secure Montrose, and prevent his escape, he

divided his army into two parts, one of which he sent off in the direction

of the Grampians, to prevent Montrose from entering the Highlands; and the

other followed directly in the rear of Montrose. He thus expected to be

able to cut off Montrose entirely, and to encourage his men to the

pursuit, he offered a reward of 20,000 crowns to any one who should bring

him Montrose’s head. Baillie’s cavalry soon came up with Montrose’s

rear, but they were so well received by the musketeers, who brought down

some of them, that they became very cautious in their approaches. The

darkness of the night soon put an end to the pursuit, and Montrose

continued unmolested his march to Arbroath, in the neighbourhood of which

he arrived about midnight. His troops had now marched upwards of 40 miles,

17 of which they had performed in a few hours, in the face of a large

army, and had passed two nights and a day without sleep; but as their

safety might be endangered by allowing them to repose till daylight,

Montrose entreated them to proceed on their march. Though almost exhausted

with incessant fatigue, and overpowered with drowsiness, they readily

obeyed the order of their general, and, after a short halt, proceeded on

their route in a northwesterly direction. They arrived at the South Esk

early in the morning, which they crossed, at sunrise, near Carriston

Castle.

Montrose now sent notice to

the party which he had despatched from Dunkeld to Brechin, with his

baggage, to join him, but they had, on hearing of his retreat, already

taken refuge among the neighbouring hills. Baillie, who had passed the

night at Forfar, now considered that he had Montrose completely in his

power; but, to his utter amazement, not a trace of Montrose was to be seen

next morning. Little did he imagine that Montrose had passed close by him

during the night, and eluded his grasp. Chagrined at this unexpected

disappointment, Baillie, without waiting for his foot, galloped off at

full speed to overtake Montrose, and, with such celerity did he travel,

that he was close upon Montrose before the latter received notice of his

approach. The whole of Montrose’s men, with the exception of a few

sentinels, were now stretched upon the ground, in a state of profound

repose, and, so firmly did sleep hold their exhausted frames in its grasp,

that it was with the utmost difficulty that they could be aroused from

their slumbers, or made sensible of their danger. The sentinels, it is

said, had even to prick some of them with their swords, before they could

be awakened, and when at length the sleepers were aroused they

effected a retreat, after some skirmishing, to the foot of the Grampians,

about three miles distant from their camp, and retired, thereafter,

through Glenesk into the interior without further molestation.

This memorable retreat is

certainly one of the most extraordinary events which occurred during the

whole of Montrose’s campaigns. It is not surprising, that some of the

most experienced officers in Britain, and in France and Germany,

considered it the most splendid of all Montrose’s achievements.

Being now secure from all

danger in the fastnesses of the Grarnpians, Montrose allowed his men to

refresh themselves for some days. Whilst enjoying this necessary

relaxation from the fatigues of the field, intelligence was brought to

Montrose that a division of the covenanting army, under Hurry, was in fall

march on Aberdeen, with an intention of proceeding into Moray. Judging

that an attack upon the possessions of the Gordons would be one of Hurry’s

objects, Montrose despatched Lord Gordon with his horse to the north, for

the purpose of assisting his friends in case of attack.

It was not in the nature of

Montrose to remain inactive for any length of time, and an occurrence, of

which he had received notice had lately taken place, which determined him

to return a second time to Dunkeld. This was the escape of Viscount Aboyne,

and some other noblemen and gentlemen, from Carlisle, who, he was

informed, were on their way north to join him. Apprehensive that they

might be interrupted by Baillie’s troops, he resolved to make a

diversion in their favour, and, by drawing off the attention of Baillie,

enable them the more effectually to elude observation. Leaving, therefore,

Macdonald, with about 200 men, to beat up the enemy in the neighbourhood

of Coupar-Angus, Montrose proceeded, with the remainder of his forces,

consisting only of 500 foot and 50 horse, to Dunkeld, whence he marched to

Crieff, which is about 17 miles west from Perth. It was not until he had

arrived at the latter town that Baillie, who, after his pursuit of

Montrose, had returned to Perth with his army, heard of this movement. As

Baillie was sufficiently aware of the weakness of Montrose’s force, and

as he was sure that, with such a great disparity, Montrose would not risk

a general engagement, he endeavoured to surprise him, in the hope either

of cutting him off entirely, or crippling him so effectually as to prevent

him from again taking the field. He therefore left Perth during the night

of the 7th of April, with his whole army, consisting of 2,000 foot and 500

horse, with the intention of falling upon Montrose by break of day, before

he should be aware of his presence; but Montrose’s experience had taught

him the necessity of being always upon his guard when so near an enemy’s

camp, and, accordingly, he had drawn up his army, in anticipation of

Baillie’s advance, in such order as would enable him either to give

battle or retreat.

As soon as he heard of

Baillie’s approach, Montrose advanced with his horse to reconnoitre, and

having ascertained the enemy’s strength and numbers, which were too

formidable to be encountered with his little band, brave as they were, he

gave immediate orders to his foot to retreat with speed up Strathearn, and

to retire into the adjoining passes. To prevent them from being harassed

in their retreat by the enemy’s cavalry, Montrose covered their rear

with his small body of horse, sustaining a very severe attack, which he

warmly repulsed. After a march of about eight miles, Montrose’s troops

arrived at the pass of Strathearn, of which they took immediate

possession, and Baillie, thinking it useless to follow them into their

retreat, discontinued the pursuit, and retired with his army towards

Perth. Montrose passed the night on the banks of Loch Earn, and marched

next morning through Balquidder, where he was joined, at the ford of

Cardross, by the Viscount Aboyne, the Master of Napier, Hay of Dalgetty,

and Stirling of Keir, who, along with the Earl of Nithsdale, Lord Herries,

and others, had escaped from Carlisle, as before stated.

No sooner had Baillie

returned from the pursuit of Montrose than intelligence was brought him

that Macdonald, with the 200 men which Montrose had left with him, had

burnt the town of Coupar-Angus, —that he had wasted the lands of Lord

Balnerino, —kiIled Patrick Lindsay, the minister of Coupar, —and

finally, after routing some troopers of Lord Balcarras, and carrying off

their horses and arms, had fled to the hills. This occurrence, withdrawing

the attention of Baillie from Montrose’s future movements, enabled the

latter to proceed to the north without opposition.

Montrose had advanced as

far as Loch Katrine, when a messenger brought him intelligence that

General Hurry was in the Enzie with a considerable force, that he had been

joined by some of the Moray-men, and, after plundering and laying waste

the country, was preparing to attack Lord Gordon, who had not a sufficient

force to oppose him. On receiving this information, Montrose resolved to

proceed immediately to the north to save the Gordons from the destruction

which appeared to hang over them, hoping that, with such accessions of

force as he might obtain in his march, united with that under Lord Gordon,

he would succeed in defeating Hurry before Baillie should be aware of his

movements.

He, therefore, returned

through Balquidder, marched, with rapid strides, along the side of Loch

Tay, through Athole and Angus, and, crossing the Grampian hills, proceeded

down the Strath of Glenmuck. In his march, Montrose was joined by the

Athole-men and the other Highlanders who had obtained, or rather taken

leave of absence after the battle of Inverlochy, and also by Macdonald and

his party. On arriving in the neighbourhood of Auchindoun, he was met by

Lord Gordon, at the head of 1,000 foot and 200 horse. Montrose crossed the

Dee on the 1st of May, at the mill of Crathie -—having provided himself

with ammunition from a ship in Aberdeen harbour -—continued his march

towards the Spey, and before Hurry was even aware that the enemy had

crossed the Grampians, he found them within six miles of his camp. The

sudden appearance of Montrose with such a superior force —for Hurry had

only at this time about 1,000 foot and 200 horse—greatly alarmed him,

and raising his camp, he crossed the Spey in great haste, with the

intention of marching to Inverness, where he would be joined by the troops

of the garrison, and receive large reinforcements from the neighbouring

counties. Montrose immediately pursued him, and followed close upon his

heels to the distance of 14 miles beyond Forres, when, favoured by the

darkness of the night, Hurry effected his escape, with little loss, and

arrived at Inverness.

The panic into which Hurry

had been thrown soon gave way to a very different feeling, as he found the

Earls of Seaforth and Sutherland with their retainers, and the clan

Fraser, and others from Moray and Caithness, all assembled at Inverness,

as he had directed. This accession of force increased his army to 3,500

foot and 400 horse. He therefore resolved to act on the offensive, by

giving battle to Montrose immediately.

Montrose had taken up a

position at the village of Auldearn, about three miles south-east from

Nairn, on the morning after the pursuit. In the course of the day, Hurry

advanced with all his forces, including the garrison of Inverness, towards

Nairn; and, on approaching Auldearn, formed his army in order of battle.

Montrose’s force, which had been greatly weakened by the return of the

Athole-men and other Highlanders to defend their country from the

depredations of Baillie’s army, now consisted of only 1,500 foot and 250

horse. It was not, therefore, without great reluctance, that he resolved

to risk a battle with an enemy more than double in point of numbers, and

composed in great part of veteran troops; but, pressed as he was by Hurry,

and in danger of being attacked in his rear by Baillie, who was advancing

by forced marches to the north, he had no alternative but to hazard a

general engagement. He therefore instantly looked about him for an

advantageous position.

The village of Auldearn

stands upon a height, behind which, or on the east, is a valley,

overlooked by a ridge of little eminences, running in a northerly

direction, and which almost conceals the valley from view. In this hollow

Montrose arranged his forces in order of battle. Having formed them into

two divisions, he posted the right wing on the north of the village, at a

place where there was a considerable number of dikes and ditches. This

body, which consisted of 400 men, chiefly Irish, was placed under the

command of Macdonald. On taking their stations, Montrose gave them strict

injunctions not to leave their position on any account, as they were

effectually protected by the walls around them, not only from the attacks

of cavalry, but of foot, and could, without much danger to themselves,

keep up a galling and destructive fire upon their assailants. In order to

attract the best troops of the enemy to this difficult spot where they

could not act, and to make them believe that Montrose commanded this wing,

he gave the royal standard to Macdonald, intending, when they should get

entangled among the bushes and dikes, with which the ground to the right

was covered, to attack them himself with his left wing; and to enable him

to do so the more effectually, he placed the whole of his horse and the

remainder of the foot on the left wing to the south of the village. The

former he committed to the charge of Lord Gordon, reserving the command of

the latter to himself. After placing a few chosen foot with some cannon in

front of the village, under cover of some dikes, Montrose firmly awaited

the attack of the enemy.

Hurry divided his foot and

his horse each into two divisions. On the right wing of the main body of

the foot, which was commanded by Campbell of Lawers, Hurry placed the

regular cavalry which he had brought from the south, and on the left the

horse of Moray and the north, under the charge of Captain Drummond. The

other division of foot was placed behind as a reserve, and commanded by

Hurry himself.

When Hurry observed the

singular position which Montrose had taken up, he was utterly at a loss to

guess his designs, and though it appeared to him, skilful as he was in the

art of war, a most extraordinary and novel sight, yet, from the well known

character of Montrose, he was satisfied that Montrose’s arrangements

were the result of a deep laid scheme. But what especially excited the

surprise of Hurry, was the appearance of the large yellow banner or royal

standard in the midst of a small body of foot stationed among hedges and

dikes and stones, almost isolated from the horse and the main body of the

foot. To attack this party, at the head of which he naturally supposed

Montrose was, was his first object. This was precisely what Montrose had

wished; his snare proved successful. With the design of overwhelming at

once the right wing, Hurry despatched towards it the best of his horse and

all his veteran troops, who made a furious attack upon Macdonald’s

party, the latter defending themselves bravely behind the dikes and

bushes. The contest continued for some time on the right with varied

success, and Hurry, who had plenty of men to spare, relieved those who

were engaged by fresh troops. Montrose, who kept a steady eye upon the

motions of the enemy, and watched a favourable opportunity for making a

grand attack upon them with the left wing, was just preparing to carry his

design into execution, when a confidential person suddenly rode up to him

and whispered in his ear that the right wing had been put to flight.

This intelligence was not,

however, quite correct. It seems that Macdonald who, says Wishart,

"was a brave enough man, but rather a better soldier than a general,

extremely violent, and daring even to rashness," had been so provoked

with the taunts and insults of the enemy, that in spite of the express

orders he had received from Montrose on no account to leave his position,

he had unwisely advanced beyond it to attack the enemy, and though he had

been several times repulsed he returned to the charge. But he was at last

borne down by the great numerical superiority of the enemy’s horse and

foot, consisting of veteran troops, and forced to retire in great disorder

into an adjoining enclosure. Nothing, however, could exceed the admirable

manner in which he managed this retreat, and the courage he displayed

while leading off his men. Defending his body with a large target, he

resisted, single-handed, the assaults of the enemy, and was the last man

to leave the field. So closely indeed was he pressed by Hurry’s

spearmen, that some of them actually came so near him as to fix their

spears in his target, which he cut off by threes or fours at a time with

his broadsword.

It was during this retreat

that Montrose received the intelligence of the flight of the right wing;

but he preserved his usual presence of mind, and to encourage his men, who

might get alarmed at hearing such news, he thus addressed Lord Gordon,

loud enough to be heard by his troops, "What are we doing, my Lord?

Our friend Macdonald has routed the enemy on the right and is carrying all

before him. Shall we look on and let him carry off the whole honour of the

day?" A crisis had arrived, and not a moment was to be lost.

Scarcely, therefore, were the words out of Montrose’s mouth, when he

ordered his men to charge the enemy. When his men were advancing to the

charge, Captain or Major Drummond, who commanded Hurry’s horse, made an

awkward movement by wheeling about his men, and his horse coming in

contact with the foot, broke their ranks and occasioned considerable

confusion. Lord Gordon seeing this, immediately rushed in upon Drummond’s

horse with his party and put them to flight. Montrose followed hard with

the foot, and attacked the main body of Hurry’s army, which he routed

after a powerful resistance. The veterans in Hurry’s army, who had

served in Ireland, fought manfully, and chose rather to be cut down

standing in their ranks than retreat; but the new levies from Moray, Ross,

Sutherland, and Caithness, fled in great consternation. They were pursued

for several miles, and might have been all killed or captured if Lord

Aboyne had not, by an unnecessary display of ensigns and standards, which

he had taken from the enemy, attracted the notice of the pursuers, who

halted for some time under the impression that a fresh party of the enemy

was coming up to attack them. In this way Hurry and some of his

troops, who were the last to leave the field of battle, as well as the

other fugitives, escaped from the impending danger, and arrived at

Inverness the following morning. As the loss of this battle was mainly

owing to Captain Drummond, he was tried by a court-martial at Inverness,

and condemned to be shot, a sentence which was carried into immediate

execution. He was accused of having betrayed the army, and it is said that

he admitted that after the battle had commenced he had spoken with the

enemy.

The number of killed on

both sides has been variously stated. That on the side of the Covenanters

has been reckoned by one writer at 1,000, by another at 2,000,

and by a third at 3,000 men. Montrose, on the other hand, is

said by the first of these authors to have lost about 200 men, while the

second says that he had only "some twenty-four gentlemen hurt, and

some few Irish killed," and Wishart informs us that Montrose only

missed one private man on the left, and that the right wing, commanded by

Macdonald, "lost only fourteen private men." The clans who had

joined Hurry suffered considerably, particularly the Frasers, who, besides

unmarried men, are said to have left dead on the field no less than 87

married men. Among the principal covenanting officers who were slain were

Colonel Campbell of Lawers, Sir John and Sir Gideon Murray, and Colonel

James Campbell, with several other officers of inferior note. The laird of

Lawers’s brother, Archibald Campbell, and a few other officers, were

taken prisoners. Captain Macdonald and William Macpherson of Invereschie

were the only persons of any note killed on Montrose’s side. Montrose

took several prisoners, whom, with the wounded, he treated with great

kindness. Such of the former as expressed their sorrow for having joined

the ranks of the Covenanters he released—others who were disposed to

join him he received into his army, but such as remained obstinate he

imprisoned. Besides taking 16 standards from the enemy, Montrose got

possession of the whole of their baggage, provisions, and ammunition, and

a considerable quantity of money and valuable effects. The battle of

Auldearn was fought on the 4th of May, according to Wishart, and

on the 9th according to others, in the year 1645.

The immense disproportion

between the numbers of the slain on the side of the Covenanters and that

of the prisoners taken by Montrose evidently shows that very little

quarter had been given, the cause of which is said to have been the murder

of James Gordon, younger of Rhiny, who was killed by a party from the

garrison of Spynie, and by some of the inhabitants of Elgin, at Struders,

near Forres, where he had been left in consequence of a severe wound he

had received in a skirmish during Hurry’s first retreat to Inverness.

But Montrose revenged himself still farther by advancing to Elgin and

burning the houses of all those who had been concerned in the murder, at

the same time sending out a party to treat in a similar way the

town of Garmouth belonging to the laird of Innes.

While these proceedings

were going on, Montrose sent his whole baggage, booty, and warlike stores

across the Spey, which he himself crossed upon the 14th of May, proceeding

to Birkenbog, the seat of "a great Covenanter," where he took up

his head quarters. He quartered his men in the neighbourhood, and, during

a short stay at Birkenbog, he sent out different parties of his troops to

scour the country, and take vengeance on the Covenanters.

When General Baillie first

heard of the defeat of his colleague, Hurry, at Auldearn, he was lying at

Cromar, with his army. He had, in the beginning of May, after Montrose’s

departure to the north, entered Athole, which he had wasted with fire and

sword, and had made an attempt upon the strong castle of Blair, in which

many of the prisoners taken at the battle of Inverlochy were confined;

but, not succeeding in his enterprise, he had, after collecting an immense

booty, marched through Athole, and, passing by Kirriemuir and Fettercairn,

encamped on the Birse on the 10th of May. His force at this time amounted

to about 2,000 foot and 120 troopers. On the following day he had marched

to Cromar, where he encamped between the Kirks of Coull and Tarlan till he

should be joined by Lord Balcarras’s horse regiment. In a short time he

was joined, not only by Balcarras’s regiment, but by two foot regiments.

The ministers endeavoured to induce the country people also to join Bailie,

by "thundering out of pulpits," but "they lay still,"

says Spalding, "and would not follow him."

As soon as Baillie heard of

the defeat of Hurry, he raised his camp at Cromar, upon the 19th of May,

and hastened north. He arrived at the wood of Cochlaraehie, within two

miles of Strathbogie, before Montrose was aware of his approach. Here he

was joined by Hurry, who, with some horse from Inverness, had passed

themselves off as belonging to Lord Gordon’s party, and had thus been

permitted to go through Montrose’s lines without opposition.

It was on the 19th of May,

when lying at Birkenbog, that Montrose received the intelligence of

Baillie’s arrival in the neighbourhood of Strathbogie. Although Montrose’s

men had not yet wholly recovered from the fatigues of their late

extraordinary march and subsequent labours, and although their numbers had

been reduced since the battle of Auldearn, by the departure of some of the

Highlanders with the booty they had acquired, they felt no disinclination

to engage the enemy, but, on the contrary, were desirous of coming to

immediate action. But Montrose, although he had the utmost confidence in

the often tried courage of his troops, judged it more expedient to avoid

an engagement at present, and to retire, in the meantime, into his

fastnesses to recruit his exhausted strength, than risk another battle

with a fresh force, greatly superior to his own. In order to deceive the

enemy as to his intentions, he advanced, the same day, upon Strathbogie,

and, within view of their camp, began to make intrenchments, and raise

fortifications, as if preparing to defend himself. But as soon as the

darkness of the night prevented Baillie from discovering his motions,

Montrose marched rapidly up the south side of the Spey with his foot,

leaving his horse behind him, with instructions to follow him as soon as

daylight began to appear.

Baillie had passed the

night in the confident expectation of a battle next day, but was surprised

to learn the following morning that not a vestige of Montrose’s army was

to be seen. Montrose had taken the route to Balveny, which having been

ascertained by Baillie, he immediately prepared to follow. He,

accordingly, crossed the Spey, and after a rapid march, almost overtook

the retiring foe in Glenlivet; but Montrose, having outdistanced his

pursuers by several miles before night came on, got the start of them so

completely, that they were quite at a loss next morning to ascertain the

route he had taken, and could only guess at it by observing the traces of

his footsteps on the grass and the heather over which he had passed.

Following, therefore, the course thus pointed out, Baillie came again in

sight of Montrose; but he found that he had taken up a position, which,

whilst it almost defied approach from its rocky and woody situation,

commanded the entrance into Badenoch, from which country Montrose could,

without molestation, draw supplies of both men and provisions. To attack

Montrose in his stronghold was out of the question; but, in the hope of

withdrawing him from it, Baillie encamped his army hard by. Montrose lay

quite secure in his well-chosen position, from which he sent out parties

who, skirmishing by day, and beating up the quarters of the enemy during

the night, so harassed and frightened them, that they were obliged to

retreat to Inverness, after a stay of a few days, a measure which was

rendered still more necessary from the want of provisions and of provender

for the horses. Leaving Inverness, Baillie crossed the Spey, and proceeded

to Aberdeenshire, arriving on the 3d of June at Newton, in the Garioch,

"where he encamped, destroying the country, and cutting the green

growing crops to the very clod."

Having got quit of the

presence of Baillie’s army, Montrose resolved to make a descent into

Angus, and attack the Earl of Crawford, who lay at the castle of Newtyle

with an army of reserve to support Baillie, and to prevent Montrose from

crossing the Forth, and carrying the war into the south. This nobleman,

who stood next to Argyle, as head of the Coyenanters, had often complained

to the Estates against Argyle, whose rival he was, for his inactivity and

pusillanimity; and having insinuated that he would have acted a very

different part had the command of such an army as Argyle had, been

intrusted to him, he had the address to obtain the command of the army now

under him, which had been newly raised; but the earl was without military

experience, and quite unfit to cope with Montrose.

Proceeding through Badenoch,

Montrose crossed the Grampians, and arrived by rapid marches on the banks

of the river Airly, within seven miles of Crawfords camp, but was

prevented from giving battle by the desertion of the Gordons and their

friends, who almost all returned to their country.

He now formed the

resolution to attack Baillie himself, but before he could venture on such

a bold step, he saw that there was an absolute necessity of making some

additions to his force. With this view he sent Sir Nathaniel Gordon, an

influential cavalier, into the north before him, to raise the Gordons and

the other royalists; and, on his march north through Glenshee and the

Braes of Mar, Montrose despatched Macdonald into the remoter Highlands

with a party to bring him, as speedily as possible, all the forces he

could. Judging that the influence and authority of Lord Gordon might

greatly assist Sir Nathaniel, he sent him after him, and Montrose himself

encamped in the country of Cromar, waiting for the expected

reinforcements.

In the meantime, Baillie

lay in camp on Dee-side, in the lower part of Mar, where he was joined by

Crawford; but he showed no disposition to attack Montrose, who, from the

inferiority, in point of number, of his forces, retired to the old castle

of Kargarf. Crawford did not, however, remain long, with Baillie; but,

exchanging a thousand of his raw recruits for a similar number of Baillie’s

veterans, he returned with these, and the remainder of his army, through

the Mearns into Angus, as if he intended some mighty exploit; he,

thereafter, entered Athole, and in imitation of Argyle, plundered and

burnt the country.

Raising his camp, Baillie

marched towards Strathbogie to lay siege to the Marquis of Huntly’s

castle, the Bog of Gight, now Gordon castle; but although Montrose had not

yet received any reinforcements, he resolved to follow Baillie and prevent

him from putting his design into execution. But Montrose had marched

scarcely three miles when he was observed by Baillie’s scouts, and at

the same time ascertained that Baillie had taken up a strong position on a

rising ground above Keith, about two miles off. Next morning Montrose, not

considering it advisable to attack Baillie in the strong position he

occupied, sent a trumpeter to him offering to engage him on open ground,

but Baillie answered the hostile message by saying, that he would not

receive orders for fighting from his enemy.

In this situation of

matters, Montrose had recourse to stratagem to draw Baillie from his

stronghold. By retiring across the river Don, the covenanting general was

led to believe that Montrose intended to march to the south, and he was,

therefore, advised by a committee of the Estates which always accompanied

him, and in whose hands he appears to have been a mere passive instrument,

to pursue Montrose. As soon as Montrose’s scouts brought intelligence

that Baillie was advancing, he set off by break of day to the village of

Alford on the river Don, where he intended to await the enemy. When

Baillie was informed of this movement, he imagined that Montrose was in

full retreat before him, a supposition which encouraged him so to hasten

his march, that he came up with Montrose at noon at the distance of a few

miles from Alford. Montrose, thereupon, drew up his army in order of

battle on an advantageous rising ground and waited for the enemy; but

instead of attacking him, Baillie made a detour to the left with the

intention of getting into Montrose’s rear and cutting off his retreat.

Montrose then continued his march to Alford, where he passed the night.

On the following morning,

the 2d of July, the two armies were only the distance of about four miles

from each other. Montrose drew up his troops on a little hill behind the

village of Alford. In his rear was a marsh full of ditches and pits, which

would protect him from the inroads of Baillie’s cavalry should they

attempt to assail him in that quarter, and in his front stood a steep

hill, which prevented the enemy from observing his motions. He gave the

command of the right wing to Lord Gordon and Sir Nathaniel; the left he

committed to Viscount Aboyne and Sir William Rollock; and the main body

was put under the charge of Angus Macvichahister, chief of the Macdonells

of Glengarry, Drummond younger of Balloch, and Quarter-master George

Graham, a skilful officer. To Napier his nephew, Montrose intrusted a body

of reserve, which was concealed behind the hill.

Scarcely had Montrose

completed his arrangements, when he received intelligence that the enemy

had crossed the Don, and was moving in the direction of Alford. This was a

fatal step on the part of Baillie, who, it is said, was forced into battle

by the rashness of Lord Balcarras, "one of the bravest men of the

kingdom," who unnecessarily placed himself and his

regiment in a position of such danger that they could not be rescued

without exposing the whole of the covenanting army.

When Baillie arrived in the

valley adjoining the hill on which Montrose had taken up his position,

both armies remained motionless for some time, viewing each other, as if

unwilling to begin the combat. Owing to the commanding position which

Montrose occupied, the Covenanters could not expect to gain any advantage

by attacking him even with superior forces; but now, for the first time,

the number of the respective armies was about equal, and Montrose had this

advantage over his adversary, that while Baillie’s army consisted in

part of the raw and undisciplined levies which the Earl of Crawford had

exchanged for some of his veteran troops, the greater part of Montrose’s

men had been long accustomed to service. These circumstances determined

Baillie not to attempt the ascent of the hill, but to remain in the

valley, where, in the event of a descent by Montrose, his superiority in

cavalry would give him the advantage.

This state of inaction was,

however, soon put an end to by Lord Gordon, who observing a party of

Baillie’s troops driving away before them a large quantity of cattle

which they had collected in Strathbogie and the Enzie, and being desirous

of recovering the property of his countrymen, selected a body of horse,

with which he attempted a rescue. The assailed party was protected by some

dykes and enclosures, from behind which they fired a volley upon the

Gordons, which did considerable execution amongst them. Such a cool and

determined reception, attended with a result so disastrous and unexpected,

might have been attended by dangerous consequences, had not Montrose, on

observing the party of Lord Gordon giving indications as if undetermined

how to act, resolved immediately to commence a general attack upon the

enemy with his whole army. But as Baillie’s foot had intrenched

themselves amongst the dykes and fences which covered the ground at the

bottom of the hill, and could not be attacked in that position with

success, Montrose immediately ordered the horse, who were engaged with the

enemy, to retreat to their former position, in the expectation that

Baillie’s troops would leave their ground and follow them. And in this

hope he was not disappointed, for the Covenanters thinking that this

movement of the horse was merely the prelude to a retreat, advanced from

their secure position, and followed the supposed fugitives with their

whole horse and foot in regular order.

Both armies now came to

close quarters, and fought face to face and man to man with great

obstinacy for some time, without either party receding from the ground

they occupied. At length Sir Nathaniel Gordon, growing impatient at such a

protracted resistance, resolved to cut his way through the enemy’s left

wing, consisting of Lord Balcarras’s regiment of horse; and calling to

the light musketeers who lined his horse, he ordered them to throw aside

their muskets, which were now unnecessary, and to attack the enemy’s

horse with their drawn swords. This order was immediately obeyed, and in a

short time they cut a passage through the ranks of the enemy, whom they

hewed down with great slaughter. When the horse which composed Baillie’s

right wing, and which had been kept in check by Lord Aboyne, perceived

that their left had given way, they also retreated. An attempt was made by

the covenanting general to rally his left wing by bringing up the right,

after it had retired, to its support, but they were so alarmed at the

spectacle or melee which they had just witnessed on the left, where

their comrades had been cut down by the broad swords of Montrose’s

musketeers, that they could not be induced to take the place of their

retiring friends.

Thus abandoned by the

horse, Baiilie’s foot were attacked on all sides by Montrose’s forces.

They fought with uncommon bravery, and although they were cut down in

great numbers, the survivors exhibited a perseverance and determination to

resist to the last extremity. An accident now occurred, which, whilst it

threw a melancholy gloom over the fortunes of the day, and the spirits of

Montrose’s men, served to hasten the work of carnage and death. This was

the fall of Lord Gordon, who having incautiously rushed in amongst the

thickest of the enemy, was unfortunately shot dead, it is said, when

in the act of pulling Baillie, the covenanting general, from his horse,

having, it is said, in a moment of exultation, promised to his men, to

drag Baillie out of the ranks and present him before them. The Gordons, on

perceiving their young chief fall, set no bounds to their fury, and

falling upon the enemy with renewed vigour, hewed them down without mercy;

yet these brave men still showed no disposition to flee, and it was not

until the appearance of the reserve under the Master of Napier., which had

hitherto been kept out of view of the enemy at the back of the hill, that

their courage began to fail them. When this body began to descend the

hill, accompanied by what appeared to them a fresh reinforcement of

cavalry, but which consisted merely of the camp or livery boys, who had

mounted the sumpter-horses to make a display for the purpose of alarming

the enemy, the entire remaining body of the covenanting foot fled with

precipitation. A hot pursuit took place, and so great was the slaughter

that very few of them escaped. The covenanting general and his principal

officers were sawed by the fleetness of their horses, and the Marquis of

Argyle, who bad accompanied Baillie as a member of the committee, and who

was closely pursued by Glengarry and some of his Highlanders, made a

narrow escape by repeatedly changing horses.

Thus ended one of the best

contested battles which Montrose had yet fought, yet strange as the fact

may appear, his loss was, as usual, extremely trifling, Lord Gordon being

the only person of importance slain. A considerable number of Montrose’s

men, however, were wounded, particularly the Gordons, who, for a long

time, sustained the attacks of Balcarras’s horse, amongst whom were Sir

Nathaniel, and Gordon, younger of Gicht. The loss on the side of the

Covenanters was immense; by far the greeter part of their foot, and a

considerable number of their cavalry having been slain. Some prisoners

were taken from them, but their number was small, owing to their obstinacy

in refusing quarter. These were sent to Stratbbogie under an escort.

The brilliant victory was,

however, clouded by the death of Lord Gordon, "‘a very hopeful

young gentleman, able of mind and body, about the age of twenty-eight

years." Wishart gives an affecting description of the feelings

of Montrose’s army when this amiable young nobleman was killed.

"There was," he says, "a general lamentation for the loss

of the Lord Gordon, whose death seemed to eclipse all the glory of the

victory. As the report spread among the soldiers, every one appeared to be

struck dumb with the melancholy news, and a universal silence prevailed

for some time through the army. however, their grief soon burst through

all restraint, venting itself in the voice of lamentation and sorrow.

When the first transports were over the soldiers exclaimed against heaven

and earth for bereaving the king, the kingdom, and themselves, of such an

excellent young nobleman; and, unmindful of the victory or of the plunder,

they thronged about the body of their dead captain, some weeping over his

wounds and kissing his lifeless limbs; while others praised his comely

appearance even in death, and extolled his noble mind, which was enriched

with every valuable qualification that could adorn his high birth or ample

fortune: they even cursed the victory bought at so dear a rate. Nothing

could have supported the army under this immense sorrow but the presence

of Montrose, whose safety gave them joy, and not a little revived their

drooping spirits. In the meantime he could not command his grief, but

mourned bitterly over the melancholy fate of his only and dearest friend,

grievously complaining, that one who was the honour of his nation, the

ornament of the Scots nobility, and the boldest asserter of the royal

authority in the north, had fallen in the flower of his youth."

The victories of Montrose

in Scotland were more than counterbalanced by those of the parliamentary

forces in England. Under different circumstances, the success at Alford |