|

Hitherto the history of the

Highlands has been confined chiefly to the fends and conflicts of the

clans, the details of which, though interesting to their descendants,

cannot be supposed to afford the same gratification to readers at large.

We now enter upon a more important era, when the Highlanders begin to play

a much more prominent part in the theatre of our national history, and to

give a foretaste of that military prowess for which they afterwards became

so highly distinguished.

In entering upon the

details of the military achievements of the Highlanders during the period

of the civil wars, it is quite unnecessary and foreign to our purpose to

trouble the reader with a history of the rash, unconstitutional, and

ill-fated attempt of Charles I. to introduce Episcopacy into Scotland;

nor, for the same reason, is it requisite to detail minutely the

proceedings of the authors of the Covenant. Suffice it to say, that in

consequence of the inflexible determination of Charles to force English

Episcopacy upon the people of Scotland, the great majority of the nation

declared their determination "by the great name of the Lord their

God," to defend their religion against what they considered to be

errors and corruptions. Notwithstanding, however, the most positive

demonstrations on the part of the people to resist, Charles, acting by the

advice of a privy council of Scotsmen established in England, exclusively

devoted to the affairs of Scotland, and instigated by Archbishop Laud,

resolved to suppress the Covenant by open force. In order to gain time for

the necessary preparations, he sent the Marquis of Hamilton, as his

commissioner, to Scotland, who was instructed to promise "that the

practice of the liturgy and the canons should never be pressed in any

other than a fair and legal way, and that the high commission should be so

rectified as never to impugn the laws, or to be a just grievance to loyal

subjects," and that the king would pardon those who had lately taken

an illegal covenant, on their immediately renouncing it, and giving up the

bond to the commissioners.

When the Covenanters heard

of Hamilton’s approach, they appointed a national fast to be held, to

beg the blessing of God upon the kirk, and on the 10th of June, 1638, the

marquis was received at Leith, and proceeded to the capital through an

assemblage of about 60,000 Covenanters, and 500 ministers. The spirit and

temper of such a vast assemblage overawed the marquis, and he therefore

concealed his instructions. After making two successive journeys to London

to communicate the alarming state of affairs, and to receive fresh

instructions, he, on his second return, issued a proclamation, discharging

"the service book, the book of canons, and the high commission court,

dispensing with the five articles of Perth, dispensing the entrants into

the ministry from taking the oath of supremacy and of canonical obedience,

commanding all persons to lay aside the new Covenant, and take that which

had been published by the king’s father in 1589, and summoning a free

assembly of the kirk to meet in the month of November, and a parliament in

the month of May; the following year." Matters had, however,

proceeded too far for submission to the conditions of the proclamation,

and the covenanting leaders answered it by a formal protest, in which they

gave sixteen reasons, showing that to comply with the demands of the king

would be to betray the cause of God, and to act against the dictates of

conscience.

In consequence of the

opposition made to the proclamation, it was generally expected that the

king would have recalled the order for the meeting of the assembly at

Glasgow; but no prohibition having been issued, that assembly, which

consisted, besides the clergy, of one lay-elder and four lay-assessors

from every presbytery, met at the time appointed, viz., in the month of

November, 1638. After the assembly had spent a week in violent debates,

the commissioner, in terms of his instructions, declared it dissolved;

but, encouraged by the accession of the Earl of Argyle, who placed himself

at the head of the Covenanters, the members declined to disperse at the

mere mandate of the sovereign, and passed a resolution that, in spiritual

matters, the kirk was independent of the civil power, and that the

dissolution by the commissioner was illegal and void. After spending three

weeks in revising the ecclesiastical regulations introduced into Scotland

since the accession of James to the crown of England, the assembly

condemned the liturgy, ordinal, book of canons, and court of high

commission, and, assuming all the powers of legislation, abolished

episcopacy, and excommunicated the bishops themselves, and the ministers

who supported them. Charles declared their proceedings null; but the

people received them with great joy, and testified their approbation by a

national thanksgiving.

Both parties had for some time been

preparing for war, and they now hastened on their plans. In consequence of

an order from the supreme committee of the Covenanters in Edinburgh, every

man capable of bearing arms was called out and trained. Experienced

Scottish officers, who had spent the greater part of their lives in

military service in Sweden and Ger. many, returned to Scotland to place

themselves at the head of their countrymen, and the Scottish merchants in

Holland supplied them with arms and ammunition. The king advanced as far

as York with an army, the Scottish bishops making him believe that

the news of his approach would induce the Covenanters to submit themselves

to his pleasure; but he was disappointed,—for instead of submitting

themselves, they were the first to commence hostilities. About the 19th of

March, 1639, General Leslie, the covenanting general, with a few men,

surprised, and without difficulty, occupied the castle of Edinburgh, and

about the same time the Earl of Traquair surrendered Dalkeith house.

Dumbarton castle, like that of Edinburgh, was taken by stratagem, the

governor, named Stewart, being intercepted on a Sunday as he returned from

church, and made to change clothes with another gentleman and give the

password, by which means the Covenanters easily obtained possession. The

king, on arriving at Durham, despatched the Marquis of Hamilton with a

fleet of forty ships, having on board 6,000 troops, to the Frith of Forth;

but as both sides of the Frith were well fortified at different points,

and covered with troops, he was unable to effect a landing.

In the meantime, the Marquis of Huntly raised the royal

standard in the north, and as the Earl of Sutherland, accompanied by Lord

Reay, John, Master of Berridale and others, had been very busy in

Inverness and Elgin, persuading the inhabitants to subscribe the Covenant,

the marquis wrote him confidentially, blaming him for his past conduct,

and advising him to declare for the king; but the earl informed him in

reply, that it was against the bishops and their innovations, and not

against the king, that he had so acted. The earl then, in his turn,

advised the marquis to join the Covenanters, by doing which he said he

would not only confer honour on himself, but much good on his native

country; that in any private question in which Huntly was personally

interested he would assist, but that in the present affair he would not

aid him. The earl thereupon joined the Earl of Seaforth, the Master of

Berridale, Lord Lovat, Lord Reay, the laird of Balnagown, the Rosses, the

Monroes, the laird of Grant, Macintosh, the laird of Innes, the sheriff of

Moray, the baron of Kilravock, the laird of Altire, the tutor of Duffus,

and the other Covenanters on the north of the river Spey.

The Marquis of Huntly assembled his forces first at

Turriff, and afterwards at Kintore, whence he marched upon Aberdeen, which

he took possession of in name of the king. The marquis being informed

shortly after his arrival in Aberdeen, that a meeting of Covenanters, who

resided within his district, was to be held at Turriff on the 14th of

February, resolved to disperse them. He therefore wrote letters to his

chief dependents, requiring them to meet him at Turriff the same day, and

bring with them no arms but swords and "schottis" or pistols.

One of these letters fell into the hands of the Earl of Montrose, one of

the chief covenanting lords, who determined at all hazards to protect the

meeting of his friends, the Covenanters. In pursuance of this resolution,

he collected, with great alacrity, some of his best friends in Angus, and

with his own and their dependents, to the number of about 800 men, he

crossed the range of hills called the Grangebean, between Angus and

Aberdeenshire, and took possession of Turriff on the morning of the 14th

of February. When Huntly’s party arrived during the course of the day,

they were surprised at seeing the little churchyard of the village filled

with armed men; and they were still more surprised to observe them

levelling their hagbuts at them across the walls of the churchyard. Not

knowing how to act in the absence of the marquis, they retired to a place

called the Broad Ford of Towie, about two miles south from the village,

when they were soon joined by Huntly and his suite. After some

consultation, the marquis, after parading his men in order of battle along

the north-west side of the village, in sight of Montrose, dispersed his

party, which amounted to 2,000 men, without offering to attack Montrose,

on the pretence that his commission of lieu tenancy only authorised him to

act on the defensive.

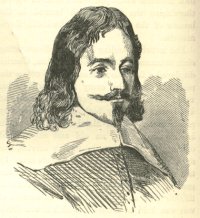

James Graham, Earl, and afterwards first Marquis of

Montrose, who played so prominent a part in the history of the troublous

times on which we are entering, was descended from a family which can be

traced back to the beginning of the 12th century. His ancestor, the Earl

of Montrose, fell at Flodden, and his grandfather became viceroy of

Scotland after James VI. ascended the throne of England. He himself was

born in 1612, his mother being Lady Margaret Ruthven, eldest daughter of

William, first Earl of Gowrie. He succeeded to the estates and title in

1626, on the death of his father, and three years after, married Magdalene

Carnegie, daughter of Lord Carnegie of Kinnaird. He pursued his studies at

St. Andrews University and Kinnaird Castle till he was about twenty years

of age, when he went to the Continent and studied at the academies of

France and Italy, returning an accomplished gentleman and a soldier. On

his return he was, for some reason, coldly received by Charles I., and it

is supposed by some that it was mainly out of chagrin on this account that

he joined the Covenanters. Whatever may have been his motive for joining

them, he was certainly an important and powerful accession to their ranks,

although, as will be seen, his adherence to them was but of short

duration. James Graham, Earl, and afterwards first Marquis of

Montrose, who played so prominent a part in the history of the troublous

times on which we are entering, was descended from a family which can be

traced back to the beginning of the 12th century. His ancestor, the Earl

of Montrose, fell at Flodden, and his grandfather became viceroy of

Scotland after James VI. ascended the throne of England. He himself was

born in 1612, his mother being Lady Margaret Ruthven, eldest daughter of

William, first Earl of Gowrie. He succeeded to the estates and title in

1626, on the death of his father, and three years after, married Magdalene

Carnegie, daughter of Lord Carnegie of Kinnaird. He pursued his studies at

St. Andrews University and Kinnaird Castle till he was about twenty years

of age, when he went to the Continent and studied at the academies of

France and Italy, returning an accomplished gentleman and a soldier. On

his return he was, for some reason, coldly received by Charles I., and it

is supposed by some that it was mainly out of chagrin on this account that

he joined the Covenanters. Whatever may have been his motive for joining

them, he was certainly an important and powerful accession to their ranks,

although, as will be seen, his adherence to them was but of short

duration.

Montrose is thus portrayed by his contemporary, Patrick

Gordon of Ruthven, author of Britane’s Diet emper. "It

cannot be denied but he was ane accomplished gentleman of many excellent

partes; a bodie not tall, but comely and well compossed in all his

liniamentes; his complexion meerly whitee, with fiaxin haire; of a stayed,

graue, and solide looke, and yet his eyes sparkling and full of lyfe; of

speach slowe, but wittie and full of sence; a presence graitfull, courtly,

and so winneing vpon the beholder, as it seemed to claime reuerence

without seweing for it; for he was so affable, so courteous, so bening, as

seemed verely to scorne ostentation and the keeping of state, and therefor

he quicklie made a conquesse of the heartes of all his followers, so as

whan he list he could haue lead them in a chaine to haue followed him with

chearefullnes in all his interpryses; and I am certanely perswaded, that

this his gratious, humane, and courteous fredome of behauiour, being

certanely acceptable befor God as well as men, was it that wanne him so

much renovne, and inabled him cheifly, in the loue of his followers, to

goe through so great interprysses, wheirin his equall had failled, altho

they exceeded him farre in power, nor can any other reason be giuen for

it, but only this that followeth. He did not seeme to affect state, nor to

claime reuerence, nor to keepe a distance with gentlemen that ware not his

domestickes; but rather in a noble yet courteouse way he seemed to slight

those vanisheing smockes of greatnes, affecting rather the reall

possession of mens heartes then the frothie and outward showe of reuerence;

and therefor was all reuerence thrust vpon him, because all did loue him,

therfor all did honour him and reuerence him, yea, haueing once acquired

there heartes, they ware readie not only to honour him, but to quarrell

with any that would not honour him, and would not spare there fortounes,

nor there derrest blood about there heartes, to the end he might be

honoured, because they sane that he tooke the right course to obtaine

honour. He had fund furth the right way to be reuerenced, and thereby was

approued that propheticke maxime which hath never failed, nor neuer shall

faille, being pronounced by the Fontaine of treuth (He that exalteth

himselfe shall be humbled); for his winneing behauiour and courteous

caryage got him more respect then those to whom they ware bound both by

the law of nature and by good reason to hawe giuen it to. Nor could any

other reason be giuen for it, but only there to much keepeing of distance,

and caryeing themselfes in a more statlye and reserued way, without

putteing a difference betuixt a free borne gentleman and a seruille or

base mynded slaue.

"This much I thought good by the way to signifie;

for the best and most waliant generall that euer lead ane armie if he

mistake the disposition of the nation whom he commandes, and will not

descend a litle till he meete with the genious of his shouldiours, on

whose followeing his grandeur and the success of his interpryses chiefely

dependeth, stryueing through a high soireing and ower winneing ambition to

drawe them to his byas with awe and not with lowe, that leader, I say,

shall neuer prewaill against his enemies with ane armie of the Scotes

nation."

Montrose had, about this time, received a commission

from the Tables—as the boards of representatives, chosen respectively by

the nobility, county gentry, clergy, and inhabitants of the burghs, were

called—to raise a body of troops for the service of the Covenanters, and

he now proceeded to embody them with extraordinary promptitude. Within one

month, he collected a force of about 3,000 horse and foot, from the

counties of Fife, Forfar, and Perth, and put them into a complete state of

military discipline. Being joined by the forces under General Leslie, he

marched upon Aberdeen, which he entered, without opposition, on the 30th

of March, the Marquis of Huntly having abandoned the town on his approach.

Some idea of the well-appointed state of this army may be formed from the

curious description of Spalding, who says, that "upon the morne,

being Saturday, they came in order of battell, weill armed, both on horse

and foot, ilk horseman having five shot at the least, with ane carabine in

his hand, two pistols by his sydes, and other two at his saddell toir; the

pikemen in their ranks, with pike and sword; the musketiers in their

ranks, with musket, musketstaffe, bandelier, sword, powder, ball, and

match; ilk company, both on horse and foot, had their captains,

lieutenants, ensignes, serjeants, and other officers and commanders, all

for the most part in buff coats, and in goodly order. They had five

colours or ensignes, whereof the Earl of Montrose had one, haveing this

motto: ‘For Religion, The Covenant, and the Countrie;’ the Earle of

Manschall had one, the Earle of Kinghorne had one, and the town of Dundie

had two. They had trumpeters to ilk company of horsemen, and drummers to

ilk company of footmen; they had their meat, drink, and other provision,

bag and baggage, carryed with them, all done be advyse of his excellence

Felt Marschall Leslie, whose councell Generall Montrose followed in this

busieness. Now, in seemly order and good array, this army came forward,

and entered the burgh of Aberdein, about ten hours in the morning, at the

Over Kirkgate Port, syne came doun throw the Broadgate, throw the

Castlegate, out at the Justice Port to the Queen’s Links directly. Here

it is to be notted that few or none of this hail army wanted ane blew

ribbin hung about his craig, doun under his left arme, which they called

the Covenanters’ Ribbin. But the Lord Gordon, and some other of

the marquess’ bairnes and familie, had ane ribbin when he was dwelling

in the teen, of ane reid flesh cullor which they wore in their hatts, and

called it The Royall Ribbin, as a signe of their love and loyalltie

to the king. In despyte and derision thereof this blew ribbin was worne,

and called the Covenanters’ Ribbin, be the hail souldiers of the

army, and would not hear of the royall ribbin; such was their pryde and

malice."

At Aberdeen Montrose was joined the same day by Lord

Fraser, the Master of Forbes, the laird of Dalgettie, the tutor of

Pitsligo, the Earl Marshal’s men in Buchan, with several other gentlemen

and their tenants, dependants, and servants, to the number of 2,000, an

addition which augmented Montrose’s army to 9,000 men. Leaving the Earl

of Kinghorn with 1,500 men to keep possession of Aberdeen, Montrose

marched the same day towards Kintore, where he encamped that night.

Halting all Sunday, he proceeded on the Monday to Inverury, where he again

pitched his camp. The Marquis of Huntly grew alarmed at this sudden and

unexpected movement, and thought it now time to treat with such a

formidable foe for his personal safety. He, therefore, despatched Robert

Gordon of Straloch and Doctor Gordon, an Aberdeen physician, to Montrose’s

camp, to request an interview. The marquis proposed to meet him on a moor

near Blackhall, about two miles from the camp, with 11 attendants each,

with no arms but a single sword at their side. After consulting with Field

Marshal Leslie and the other officers, Montrose agreed to meet the

marquis, on Thursday the 4th of April, at the place mentioned. The parties

accordingly met. Among the eleven who attended the marquis were his son

James, Lord Aboyne, and the Lord Oliphant. Lords Elcho and Cowper were of

the party who attended Montrose. After the usual salutation they both

alighted and entered into conversation; but, coming to no understanding,

they adjourned the conference till the following morning, when the marquis

signed a paper obliging himself to maintain the king’s authority,

"the liberty of church and state, religion and laws." He

promised at the same time to do his best to make his friends, tenants, and

servants subscribe the Covenant. The marquis, after this

arrangement, went to Strathbogie, and Montrose returned with his army to

Aberdeen, the following day.

The marquis had not been many days at Strathbogie, when

he received a notice from Montrose to repair to Aberdeen with his two

sons, Lord Gordon and Viscount Aboyne, for the ostensible purpose of

assisting the committee in their deliberations as to the settlement of the

disturbances in the north.’ On Huntly receiving an assurance from

Montrose and the other covenanting leaders that no attempt should be made

to detain himself and his sons as prisoners, he complied with Montrose’s

invitation, and repairing to Aberdeen, he took up his quarters in the

laird of Pitfoddel’s house.

The arrest of the marquis, which followed, has been

attributed, not without reason, to the intrigues of the Frasers and the

Forbeses, who bore a mortal antipathy to the house of Huntly, and who were

desirous to see the " Cock of the North," as the powerful head

of that house was popularly called, humbled. But, be these conjectures as

they may, on the morning after the marquis’s arrival at Aberdeen, viz.,

on the 11th April, a council of the principal officers of Montrose’s

army was held, at which it was determined to arrest the marquis and Lord

Gordon, his eldest son, and carry them to Edinburgh. It was not, however,

judged advisable to act upon this resolution immediately, and to do away

with any appearance of treachery, Montrose and his friends invited the

marquis and his two sons to supper the following evening. During the

entertainment the most friendly civilities were passed on both sides, and,

after the party had become somewhat merry, Montrose and his friends hinted

to the marquis the expediency, in the present posture of affairs, of

resigning his commission of lieutenancy. They also proposed that he should

write a letter to the king along with the resignation of his commission,

in favour of the Covenanters, as good and loyal subjects; and that he

should despatch the laird of Cluny, the following morning, with the letter

and resignation. The marquis, seeing that his commission was altogether

unavailable, immediately wrote out, in presence of the meeting, a

resignation of it, and a letter of recommendation as proposed, and, in

their presence, delivered the same to the laird of Cluny, who was to set

off the following morning with them to the king. It would appear that

Montrose was not sincere in making this demand upon the marquis, and that

his object was, by calculating on a refusal, to make that the ground for

arresting him; for the marquis had scarcely returned to his lodgings to

pass the night, when an armed guard was placed round the house, to prevent

him from returning home, as he intended to do, the following morning.

When the marquis rose, next morning, he was surprised

at receiving a message from the covenanting general, desiring his

attendance at the house of the Earl Marshal; and he was still farther

surprised, when, on going out, along with his two sons, to the appointed

place of meeting, he found his lodging beset with sentinels. The marquis

was received by Montrose with the usual morning salutation, after which,

he proceeded to demand from him a contribution for liquidating a loan of

200,000 merks, which the Covenanters had borrowed from Sir William Dick, a

rich merchant of Edinburgh. To this unexpected demand the marquis replied,

that he was not obliged to pay any part thereof, not having been concerned

in the borrowing, and of course, declined to comply. Montrose then

requested him to take steps to apprehend James Grant and John Dugar, and

their accomplices, who had given considerable annoyance to the Covenanters

in the Highlands. Huntly objected, that, having now no commission, he

could not act, and that, although he had, James Grant had already obtained

a remission from the king; and as for John Dugar, he would concur, if

required, with the other neighbouring proprietors in an attempt to

apprehend him. The earl, finally, as the Covenant, he said, admitted of no

standing hatred or feud, required the marquis to reconcile himself to

Crichton, the laird of Frendraught, but this the marquis positively

refused to do. Finding, as he no doubt expected, the marquis quite

resolute in his determination to resist these demands, the earl suddenly

changed his tone, and thus addressed the marquis, apparently in the most

friendly terms, "My lord, seeing we are all now friends, will you go

south to Edinburgh with us?" Huntly answered that he would not—that

he was not prepared for such a journey, and that he was just going to set

off for Strathbogie. "Your lordship," rejoined Montrose,

"will do well to go with us." The marquis now perceiving

Montrose’s design, accosted him thus, "My lord, I came here to this

town upon assurance that I should come and go at my own pleasure, without

molestation or inquietude; and now I see why my lodging was guarded, and

that ye mean to take me to Edinburgh, whether I will or not. This conduct,

on your part, seems to me to be neither fair nor honourable." He

added, "My lord, give me back the bond which I gave you at Inverury,

and you shall have an answer." Montrose thereupon delivered the bond

to the marquis. Huntly then inquired at the earl, "Whether he would

take him to the south as a captive, or willingly of his own mind?"

"Make your choice," said Montrose. "Then," observed

the marquis, "I will not go as a captive, but as a volunteer."

The marquis thereupon immediately returned to his lodging, and despatched

a messenger after the laird of Cluny, to stop him on his journey."

It was the intention of Montrose to take both the

marquis and his sons to Edinburgh, but Viscount Aboyne, at the desire of

some of his friends, was released, and allowed to return to Strathbogie.

On arriving at Edinburgh, the marquis and his son, Lord Gordon, were

committed close prisoners to the castle of Edinburgh, and the Tables

"appointed five guardians to attend upon him and his son night and

day, upon his own expenses, that none should come in nor out but by their

sight." On being solicited to sign the Covenant, Huntly

issued a manifesto characterized by magnanimity and the most steadfast

loyalty, concluding with the following words:—" For my oune part, I

am in your power; and resolved not to leave that foul title of traitor as

ane inheritance upon my posteritye. Yow may tacke my heade from my

shoulders, but not my heart from my soveraigne."

Some time after the departure of Montrose’s army to

the south, the Covenanters of the north appointed a committee meeting to

be held at Turriff, upon Wednesday, 24th April, consisting of the Earls

Marshal and Seaforth, Lord Fraser, the Master of Forbes, and some of their

kindred and friends. All persons within the diocese, who had not

subscribed the Covenant, were required to attend this meeting for the

purpose of signing it, and failing compliance, their property was to be

given up to indiscriminate plunder. As neither Lord Aboyne, the laird of

Banff, nor any of their friends and kinsmen, had subscribed the Covenant,

nor meant to do so, they resolved to protect themselves from the

threatened attack. A preliminary meeting of the heads of the northern

Covenanters was held on the 22d of April, at Monymusk, where they learned

of the rising of Lord Aboyne and his friends. This intelligence induced

them to postpone the meeting at Turriff till the 26th of April, by which

day they expected to be joined by several gentlemen from Caithness,

Sutherland, Ross, Moray, and other quarters. At another meeting, however,

on the 24th of April, they postponed the proposed meeting at Turriff, sine

die, and adjourned to Aberdeen; but as no notice had been sent of the

postponement to the different covenanting districts in the north, about

1,500 men assembled at the place of meeting on the 26th of April, and were

quite astonished to find that the chiefs were absent. Upon an explanation

taking place, the meeting was adjourned till the 20th of May.

Lord Aboyne had not been idle during this interval,

having collected about 2,000 horse and foot from the Highlands and

Lowlands, with which force he had narrowly watched the movements of the

Covenanters. Hearing, however, of the adjournment of the Turriff meeting,

his lordship, at the entreaty of his friends, broke up his army, and went

by sea to England to meet the king, to inform him of the precarious state

of affairs in the north. Many of his followers, such as the lairds of

Gight, Haddo, Udney, Newton, Pitmedden, Faveran, Tippertie, Harthill, and

others, who had subscribed the Covenant, regretted his departure; but as

they had gone too far to recede, they resolved to continue their forces in

the field, and held a meeting on the 7th of May at Auchterless, to concert

a plan of operations.

A body of the Covenanters, to the number of about

2,000, having assembled at Turriff as early as the 13th of May, the

Gordons resolved instantly to attack them, before they should be joined by

other forces, which were expected to arrive before the 20th. Taking along

with them four brass field-pieces from Strathbogie, the Gordons, to the

number of about 800 horse and foot, commenced their march on the 13th of

May, at ten o’clock at night, and reached Turriff next morning by

day-break, by a road unknown to the sentinels of the covenanting army. As

soon as they approached the town, the commander of the Gordons ordered the

trumpets to be sounded and the drums to be beat, the noise of which was

the first indication the Covenanters had of their arrival. Being thus

surprised, the latter had no time to make any preparations for defending

themselves. They made, indeed, a short resistance, but were soon dispersed

by the fire from the field-pieces, leaving behind them the lairds of Echt

and Skene, and a few others, who were taken prisoners. The loss on either

side, in killed and wounded, was very trifling. This skirmish is called by

the writers of the period, "the Trott of Turray."

The successful issue of this trifling affair had a

powerful effect on the minds of the victors, who forthwith marched on

Aberdeen, which they entered on the 15th of May. They expelled the

Covenanters from the town, and were there joined by a body of men from the

Braes of Mar under the command of Donald Farquharson of Tulliegarmouth,

and the laird of Abergeldie, and by another party headed by James Grant,

so long an outlaw, to the number of about 500 men. These men quartered

themselves very freely upon the inhabitants, particularly on those who had

declared for the Covenant, and they plundered many gentlemen’s houses in

the neighbourhood. The house of Durris, belonging to John Forbes of

Leslie, a great Covenanter, received a visit from them. "There

was," says Spalding, "little plenishing left unconveyed away

before their comeing They gott good bear and ale, broke up girnells, and

buke bannocks at good fyres, and drank merrily upon the laird’s best

drink: syne carried away with them alse meikle victual as they could beir,

which they could not gett eaten and destroyed; and syne removed from that

to Echt, Skene, Monymusk, and other houses pertaining to the name of

Forbes, all great Covenanters".

Two days after their arrival at Aberdeen, the Gordons

sent to Dunnottar, for the purpose of ascertaining the sentiments of the

Earl Marshal, in relation to their proceedings, and whether they might

reckon on his friendship, The earl, however, intimated that he could say

nothing in relation to the affair, and that he would require eight days to

advise with his friends. This answer was considered quite unsatisfactory,

and the chiefs of the army were at a loss how to act. Robert Gordon of

Straloch, and James Burnet of Craigmylle, a brother of the laird of Leys,

proposed to enter into a negotiation with the Earl Marshal, but Sir George

Ogilvie of Banff would not listen to such a proceeding, and, addressing

Straloch, he said, "Go, if you will go; but pr’ythee, let it be as

quarter-master, to inform the earl that we are coming." Straloch,

however, went not in the character of a quarter-master, but as a mediator

in behalf of his chief. The earl said he had no intention to take up arms,

without an order from the Tables; that, if the Gordons would disperse, he

would give them early notice to re-assemble, if necessary, for their own

defence, but that if they should attack him, he would certainly defend

himself.

The army was accordingly disbanded on the 21st of May,

and the barons went to Aberdeen, there to spend a few days. The

depredations of the Highlanders, who had come down to the lowlands in

quest of plunder, upon the properties of the Covenanters, were thereafter

carried on to such an extent, that the latter complained to the Earl

Marshal, who immediately assembled a body of men out of Angus and the

Mearns, with which he entered Aberdeen on the 23d of May, causing the

barons to make a precipitate retreat. Two days thereafter the earl was

joined by Montrose, at the head of 4,000 men, an addition which, with

other accessions, made the whole force assembled at Aberdeen exceed 6,000.

Meanwhile a large body of northern Covenanters, under

the command of the Earl of Seaforth, was approaching from the districts

beyond the Spey; but the Gordons having crossed the Spey for the purpose

of opposing their advance, an agreement was entered into between both

parties that, on the Gordons retiring across the Spey, Seaforth and his

men should also retire homewards.

After spending five days in Aberdeen, Montrose marched

his army to Udney, thence to Kellie, the seat of the laird of Haddo, and

afterwards to Gight, the residence of Sir Robert Gordon, to which he laid

siege. But intelligence of the arrival of Viscount Aboyne in the bay of

Aberdeen, deranged his plans. Being quite uncertain of Aboyne’s

strength, and fearing that his retreat might be cut off, Montrose quickly

raised the siege and returned to Aberdeen. Although Lord Aboyne still

remained on board his vessel, and could easily have been prevented from

landing, Montros most unaccountably abandoned the town, and retired into

the Mearns.

Viscount Aboyne had been most graciously received by

the king, and had ingratiated himself so much with the monarch, as to

obtain the commission of lieutenancy which his father held. The king

appears to have entertained good hopes from his endeavours to support the

royal cause in the north of Scotland, and before taking leave he gave the

viscount a letter addressed to the Marquis of Hamilton, recquesting him to

afford his lordship all the assistance in his power. From whatever cause,

all the aid afforded by the Marquis was limited to a few officers and four

field-pieces: "The king," says Gordon of Sallagh, "coming

to Berwick, and business growing to a height, the armies of England and

Scotland lying near one another, his majesty sent the Viscount of Aboyne

and Colonel Gun (who was then returned out of Germany) to the Marquis of

Hamilton, to receive some forces from him, and with these forces to go to

Aberdeen, to possess and recover that town. The Marquis of Hamilton, lying

at anchor in Forth, gave them no supply of men, but sent them five ships

to Aberdeen, and the marquis himself retired with his fleet and men to the

Holy Island, hard by Berwick, to reinforce the king’s army there against

the Scots at Dunslaw." On his voyage to Aberdeen, Aboyne’s ships

fell in with two vessels, one of which contained the lairds of Banif,

Foveran, Newton, Crummie, and others, who had fled on the approach of

Montrose to Gight; and the other had on board some citizens of Aberdeen,

and several ministers who had refused to sign the Covenant, all of whom

the viscount persuaded to return home along with him.

On the 6th of June, Lord Aboyne, accompanied by the

Earls of Glencairn and Tullibardine, the lairds of Drum, Banff, Fedderet,

Foveran, and Newton, and their followers, with Colonel Gun and several

English officers, landed in Aberdeen without opposition. Immediately on

coming ashore, Aboyne issued a proclamation which was read at the cross of

Aberdeen, prohibiting all his majesty’s loyal subjects from paying any

rents, duties, or other debts to the Covenanters, and requiring them to

pay one-half of such sums to the king, and to retain the other for

themselves. Those persons who had been forced to subscribe the Covenant

against their will, were, on repentance, to be forgiven, and every person

was required to take an oath of allegiance to his majesty.

This bold step inspired the royalists with confidence,

and in a short space of time a considerable force rallied round the royal

standard. Lewis Gordon, third son of the Marquis of Huntly, a youth of

extraordinary courage, on hearing of his brother’s arrival, collected

his father’s friends and tenants, to the number of about 1,000 horse and

foot, and with these he entered Aberdeen on the 7th of June. These were

succeeded by 100 horse, sent in by the laird of Drum, and by considerable

forces led by James Grant and Donald Farquharson. Many of the Covenanters

also joined the viscount, so that his force ultimately amounted to several

thousand men. Spalding gives a sad, though somewhat ludicrous

account of the way in which Farquharson’s "hieland men"

conducted themselves while in Aberdeen. He says, " Thir saulless

lounis plunderit meit, drink, and scheip quhair ever they cam. Thay

oppressit the Oldtoun, and brocht in out of the countrie honest menis

scheip, and sold at the cross of Old Abirdein to sic as wold by, ane

scheip upone foot for ane groat. The poor men that aucht thame follouit in

and coft bak thair awin scheip agane, sic as wes left unslayne for thair

meit."

On the 10th of June the viscount left Aberdeen, and

advanced upon Kintore with an army of about 2,000 horse and foot, to which

he received daily accessions. The inhabitants of the latter place were

compelled by him to subscribe the oath of allegiance, and notwithstanding

their compliance, " the troops," says Spalding, "plundered

meat and drink, and made good fires: and, where they wanted pests, broke

down beds and boards in honest men’s houses to be fires, and fed their

horses with corn and straw that day and night." Next morning the army

made a raid upon Hall Forrest, a seat of the Earl Marshal, and the house

of Muchells, belonging to Lord Fraser; but Aboyne, hearing of a rising in

the south, returned to Aberdeen.

As delay would be dangerous to his cause in the present

conjuncture, he crossed the Dee on the 14th of June, his army amounting

altogether probably to about 3,000 horse and foot, with the intention of

occupying Stonehaven, and of issuing afresh the king’s proclamation at

the market cross of that burgh. He proceeded as far as Muchollis, or

Muchalls, the seat of Sir Thomas Burnet of Leyes, a Covenanter, where he

encamped that night. On hearing of his approach, the Earl Marshal and

Montrose posted themselves, with 1,200 men, and some pieces of ordnance

which they had drawn from Dunnottar castle, on the direct road which

Aboyne had to pass, and waited his approach.

Although Aboyne was quite aware of the position of the

Earl Marshal, instead of endeavouring to outflank him by making a detour

to the right, he, by Colonel Gun’s advice, crossed the Meagre hill next

morning, directly in the face of his opponent, who lay with his forces at

the bottom of the hill. As Aboyne descended the kill, the Earl Marshal

opened a heavy fire upon him, which threw his men into complete disorder.

The Highlanders, unaccustomed to the fire of cannon, were the first to

retreat, and in a short time the whole army gave way. Aboyne thereupon

returned to Aberdeen with some horsemen, leaving the rest of the army to

follow; but the Highlanders took a homeward course, carrying along with

them a large quantity of booty, which they gathered on their retreat. The

disastrous issue of "the Raid of Stonehaven," as this affair has

been called, has been attributed, with considerable plausibility, to

treachery on the part of Colonel Gun, to whom, on account of his great

experience, Aboyne had intrusted the command of the army.

On his arrival at Aberdeen, Aboyne held a council of

war, at which it was determined to send some persons into the Mearns to

collect the scattered remains of his army, for, with the exception of

about 180 horsemen and a few foot soldiers, the whole of the fine army

which he had led from Aberdeen had disappeared; but although the army

again mustered at Leggetsden to the number of 4,000, they were prevented

from recrossing the Dee and joining his lordship by the Marshal and

Montrose, who advanced towards the bridge of Dee with all their forces.

Aboyne, hearing of their approach, resolved to dispute with them the

passage of the Dee, and, as a precautionary measure, blocked up the

entrance to the bridge of Dee from the south by a thick wall of turf,

beside which he placed 100 musketeers upon the bridge, under the command

of LieutenantColonel Johnstone, to annoy the assailants from the small

turrets on its sides. The viscount was warmly seconded in his views by the

citizens of Aberdeen, whose dread of another hostile visit from the

Covenanters induced them to afford him every assistance in their power,

and it is recorded that the women and children even occupied themselves in

carrying provisions to the army during the contest.

The army of Montrose consisted of about 2,000 foot and

300 horse, and a large train of artillery. The forces which Lord Aboyne

had collected on the spur of the occasion were not numerous, but he was

superior in cavalry. His ordnance consisted only of four pieces of brass

cannon. Montrose arrived at the bridge of Dee on the 18th of June, and,

without a moment’s delay, commenced a furious cannonade upon the works

which had been thrown up at the south end, and which he kept up during the

whole day without producing any material effect. Lieutenant-colonel

Johnstone defended the bridge with determined bravery, and his musketeers

kept up a galling and well-directed fire upon their assailants. Both

parties reposed during the short twilight, and as soon as morning dawned

Montrose renewed his attack upon the bridge, with an ardour which seemed

to have received a fresh impulse from the unavailing efforts of the

preceding day but all his attempts were vain. Seeing no hopes of carrying

the bridge in the teeth of the force opposed to him, he had recourse to a

stratagem, by which he succeeded in withdrawing a part of Aboyne’s

forces from the defence of the bridge. That force had, indeed, been

considerably impaired before the renewal of the attack, in consequence of

a party of 50 musketeers having gone to Aberdeen to escort thither the

body of a citizen named John Forbes, who had been killed the preceding

day; to which circumstance Spalding attributes the loss of the bridge; but

whether the absence of this party had such an effect upon the fortune of

the day is by no means clear. The covenanting general, after battering

unsuccessfully the defences of the bridge, ordered a party of horsemen to

proceed up the river some distance, and to make a demonstration as if they

intended to cross. Aboyne was completely deceived by this manoeuvre, and

sent the whole of his horsemen from the bridge to dispute the passage of

the river with those of Montrose, leaving Lieutenant-colonel John-stone

and his 50 musketeers alone to protect the bridge. Montrose having thus

drawn his opponent into the snare set for him, immediately sent back the

greater part of his horse, under the command of Captain Middleton, with

instructions to renew the attack upon the bridge with redoubled energy.

This officer lost no time in obeying these orders, and Lieutenant-colonel

Johnstone having been wounded in the outset by a stone torn from the

bridge by a shot, was forced to abandon its defence, and he and his party

retired precipitately to Aberdeen.

When Aboyne saw the colours of the Covenanters flying

on the bridge of Dee, he fled with great haste towards Strathbogie, after

releasing the lairds of Purie Ogilvy and Purie Fodderinghame, whom he had

taken prisoners, and carried with him from Aberdeen. The loss on either

side during the conflict on the bridge was trifling. The only person of

note who fell on Aboyne’s side was Seaton of Pitmedden, a brave

cavalier, who was killed by a cannon shot while riding along the river

side with Lord Aboyne. On that of the Covenanters was slain another

valiant gentleman, a brother of Ramsay of Balmain. About 14 persons of

inferior note were killed on each side, including some burgesses of

Aberdeen, and several were wounded.

Montrose, reaching the north bank of the Dee, proceeded

immediately to Aberdeen, which he entered without opposition. So

exasperated were Montrose’s followers at the repeated instances of

devotedness shown by the inhabitants to the royal cause, that they

proposed to raze the town and set it on fire; but they were hindered from

carrying their design into execution by the firmness of Montrose. The

Covenanters, however, treated the inhabitants very harshly, and imprisoned

many who were suspected of having been concerned in opposing their passage

across the Dee; but an end was put to these proceedings in consequence of

intelligence being brought on the following day (June 20th) of the treaty

of pacification which had been entered into between the king and his

subjects at Berwick, upon the 18th of that month. On receipt of this news,

Montrose sent a despatch to the Earl of Seaforth, who was stationed with

his army on the Spey, intimating the pacification, and desiring him to

disband his army, with which order had instantly complied.

The articles of pacification were preceded by a

declaration on the part of the king, in which he stated, that although he

could not condescend to ratify and approve of the acts of the Glasgow

General Assembly, yet, notwithstanding the many disorders which had of

late been committed, he not only confirmed and made good whatsoever his

commissioner had granted and promised, but he also declared that all

matters ecclesiastical should be determined by the assemblies of the kirk,

and matters civil by the parliament and other inferior judicatories

established by law. To settle, therefore, "the general

distractions" of the kingdom, his majesty ordered that a free general

assembly should be held at Edinburgh on the 6th August following, at which

he declared his intention, "God willing, to be personally

present;" and he moreover ordered a parliament to meet at Edinburgh

on the 20th of the same month, for ratifying the proceedings of the

general assembly, and settling such other matters as might conduce to the

peace and good of the kingdom of Scotland. By the articles of

pacification, it was, inter alia, provided that the forces in

Scotland should be disbanded within forty-eight hours after the

publication of the declaration, and that all the royal castles, forts, and

warlike stores of every description, should be delivered up to his majesty

after the said publication, as soon as he should send to receive them.

Under the seventh and last article of the treaty, the Marquis of Huntly

and his son, Lord Gordon, and some others who had been detained prisoners

in the castle of Edinburgh by the Covenanters, were set at Liberty.

It has been generally supposed that neither party had

any sincere intention to observe the conditions of the treaty. Certain it

is, that the ink with which it was written was scarcely dry before its

violation was contemplated. On the one hand, the king, before removing his

army from the neighbourhood of Berwick, required the heads of the

Covenanters to attend him there, obviously with the object of gaining them

over to his side; but, with the exception of three commoners and three

lords, Montrose, Loudon, and Lothian, they refused to obey. It was at this

conference that Charles, who apparently had great persuasive powers, made

a convert of Montrose, who from that time determined to desert his

associates in arms and to place himself under the royal standard. The

immediate strengthening of the forts of Berwick and Carlisle, and the

provisioning of the castle of Edinburgh, were probably the suggestions of

Montrose, who would, of course, be intrusted with the secret of his

majesty’s designs. The Covenanters, on the other hand, although making a

show of disbanding their army at Dunse, in reality kept a considerable

force on foot, which they quartered in different parts of the country, to

be in readiness for the field on a short notice. The suspicious conduct of

the king certainly justified this precaution.

The general assembly met on the day fixed upon, but,

instead of attending in person as he proposed, Charles appointed the Earl

of Traquair to act as his commissioner. After abolishing the articles of

Perth, the book of canons, the liturgy, the high commission and

episcopacy, and ratifying the late Covenant, the assembly was dissolved on

the 30th of August, and another general assembly was appointed to be held

at Aberdeen on the 28th of July of the following year, 1640. The

parliament met next day, viz., on the last day of August, and as there

were no bishops to represent the third estate, fourteen minor barons were

elected in their stead. His majesty’s commissioner protested against the

vote and against farther proceedings till the king’s mind should be

known, and the commissioner immediately sent off a letter apprising him of

the occurrence. Without waiting for the king’s answer, the parliament

was proceeding with a variety of bills for securing the liberty of the

subject and restraining the royal prerogative, when it was unexpectedly

and suddenly prorogued, by an order from the king, till the 2d of June in

the following year.

If Charles had not already made up his mind for war

with his Scottish subjects, the conduct of the parliament which he had

just prorogued determined him again to have recourse to arms in

vindication of his prerogative. He endeavoured, at first, to enlist the

sympathies of the bulk of the English nation in his cause, but without

effect; and his repeated appeals to his English people, setting forth the

rectitude of his intentions and the justice of his cause, being answered

by men who questioned the one and denied the other, rather injured than

served him. The people of England were not then in a mood to embark in a

crusade against the civil and religious liberties of the north; and they

had too much experience of the arbitrary spirit of the king to imagine

that their own liberties would be better secured by extinguishing the

flame which burned in the breasts of the sturdy and enthusiastic

Covenanters.

But notwithstanding the many discouraging circumstances

which surrounded him, Charles displayed a firmness of resolution to coerce

the rebellious Scots by every means within his reach. The spring and part

of the summer of 1640 were spent by both parties in military preparations.

Field-Marshal Sir Alexander Leslie of Balgony, an old and experienced

officer who had been in foreign service, was appointed generalissimo of

the Scots army by the war committee. When mustered by the general at

Choicelee, it amounted to about 22,000 foot and 2,500 horse. A council of

war was held at Dunse at which it was determined to invade England.

Montrose, to whose command a division of the army, consisting of 2,000

foot and 500 horse, was intrusted, was absent when this meeting was held;

but, although his sentiments had, by this time, undergone a complete

change, seeing on his return no chance of preventing the resolution of the

council, he dissembled his feelings and openly approved of the plan. There

seems to be no doubt that in following this course he intended, on the

first favourable opportunity, to declare for the king, and carry off such

part of the army as should be inclined to follow him, which he reckoned at

a third of the whole.

The Earl of Argyle was commissioned by the Committee of

Estates to secure the west and central Highlands. This, the eighth Earl

and first Marquis of Argyle, had succeeded to the title only in 1638,

although he had enjoyed the estates for many years before that, as his

father had been living in Spain, an outlaw. He was born in 1598, and

strictly educated in the protestant faith as established in Scotland at

the Reformation. In 1626 he was made a privy councillor, and in 1634

appointed one of the extraordinary lords of session. In 1638, at the

General Assembly of Glasgow, he openly went over to the side of the

Covenanters, and from that time was recognised as their political head.

Argyle, in executing the task intrusted to him by the committee, appears

to have been actuated more by feelings of private revenge than by an

honest desire to carry out the spirit of his commission. The ostensible

reason for his undertaking this charge was his thorough acquaintance with

the Highlands and the Highlanders, and his ability to command the services

of a large following of his own. "But the cheefe cause,"

according to Gordon of Rothiemay, "though least mentioned,

was Argylle, his spleene that he carryed upon the accompt of former

disobleedgments betwixt his family and some of the Highland clans:

therefore he was glade now to gett so faire a colour of revenge upon the

publicke score, which he did not lett slippe. Another reasone he had

besyde; it was his designe to swallow upp Badzenoch and Lochaber, and some

landes belonging to the Mackdonalds, a numerous trybe, but haters of, and

aeqwally hated by Argylle." He had some hold on these two districts,

as, in 1639, he had become security for some of Huntly’s debts to the

latter’s creditors. Argyle managed to seduce from their allegiance to

Huntly the clan Cameron in Lochaber, who bore a strong resentment against

their proper chief on account of some supposed injury done to the clan by

the former marquis. Although they had little relish for the Covenant,

still to gratify their revenge, they joined themselves to Argyle. A tribe

of the Macdonalds who inhabited Lochaber, the Macranalds of Keppoch, who

remained faithful to Huntly, met with very different treatment at the

hands of Argyle, who devastated their district and burnt down their chief’s

dwelling at Keppoch.

During

this same summer (July 1640), Argyle, who had raised an army of about

5,000 men, made a devastating raid into the district of Forfarshire

belonging to the Earl of Airly. He made first for Airly castle, about five

miles north of Meigle, which, in the absence of the earl in England, was

held by his son Lord Ogilvie, who had recently maintained it against

Montrose. When Argyle came up, Ogilvie saw that resistance was hopeless,

and abandoned the castle to the tender mercy of the enemy. Argyle without

scruple razed the place to the ground, and is said to have shown himself

so "extremely earnest" in the work of demolition "that he

was seen taking a hammer in his hande and knocking down the hewed work of

the doors and windows till he did sweat for heat at his work." Argyle’s

men carried off all they could from the house and the surrounding

district, and rendered useless what they were compelled to leave behind. During

this same summer (July 1640), Argyle, who had raised an army of about

5,000 men, made a devastating raid into the district of Forfarshire

belonging to the Earl of Airly. He made first for Airly castle, about five

miles north of Meigle, which, in the absence of the earl in England, was

held by his son Lord Ogilvie, who had recently maintained it against

Montrose. When Argyle came up, Ogilvie saw that resistance was hopeless,

and abandoned the castle to the tender mercy of the enemy. Argyle without

scruple razed the place to the ground, and is said to have shown himself

so "extremely earnest" in the work of demolition "that he

was seen taking a hammer in his hande and knocking down the hewed work of

the doors and windows till he did sweat for heat at his work." Argyle’s

men carried off all they could from the house and the surrounding

district, and rendered useless what they were compelled to leave behind.

From Airly, Argyle proceeded to a seat belonging to

Lord Ogilvie, Forthar in Glenisla, the "bonnie house o’ Airly,"

of the well-known song. Here he behaved in a manner for which it would be

difficult for his warmest supporters to find the shadow of an excuse, even

taking into consideration the roughness of the times. The place is said by

Gordon to have been "no strength," so that there is still less

excuse for his conduct. He treated Forthar in the same way that he did

Airly, and although Lady Ogilvie, who at the time was close on her

confinement, asked Argyle to stay proceedings until she gave birth to her

infant, he without scruple expelled her from the house, and proceeded with

his work of destruction. Not only so, however, but "the Lady Drum,

Dame Marian Douglas, who lived at that time in Kelly, hearing tell what

extremity her grandchild, the Lady Ogilvy, was reduced to, did send a

commission to Argyle, to whom the said Lady Drum was a kinswoman,

requesting that, with his license, she might admit into her own house, her

grandchild, the Lady Ogilvy, who at that time was near her delivery; but

Argyle would give no license. This occasioned the Lady Drum for to fetch

the Lady Ogilvie to her house of Kelly, and for to keep her there upon all

hazard that might follow."

At the same time Argyle "was not forgetful to

remember old quarrels to Sir John Ogilvie of Craigie." He sent a

sergeant to Ogilvie’s house to warn him to leave it, but the sergeant

thought Argyle must have made some mistake, as he found it no more than a

simple unfortified country house, occupied only by a sick gentlewoman and

some servants. The sergeant returned and told this to Argyle, who waxed

wroth and told him it was his duty simply to obey orders, commanding him

at the same time to return and "deface and spoil the house."

After the sergeant had received his orders, Argyle was observed to turn

round and repeat to himself the Latin political maxim A bscindantur qui

nos perturbant, "a maxime which many thought that he practised

accurately, which he did upon the account of the proverb consequential

thereunto, and which is the reason of the former, which Argyle was

remarked likewise to have often in his mouth as a choice aphorism, and

well observed by statesmen, Quod mortui non mordent."

Argyle next proceeded against the Earl of Athole, who,

with about 1,200 followers, was lying in Breadalbane, ready to meet him.

Argyle, whose army was about five times the size of Athole’s, instead of

giving fight, managed by stratagem to capture Athole and some of his

friends, whom he sent to the Committee of Estates at Edinburgh.

Argyle, after having thus gratified his private revenge

and made a show of quieting the Highlands, returned to the lowlands.

On the 20th of August General Leslie crossed the Tweed

with his army, the van of which was led by Montrose on foot. This task,

though performed with readiness and with every appearance of good will,

was not voluntarily undertaken, but had been devolved upon Montrose by

lot; none of the principal officers daring to take the lead of their own

accord in such a dangerous enterprise. There can be no doubt that Montrose

was insincere in his professions, and that those who suspected him were

right in thinking that in his heart he was turned Royalist, a

supposition which his correspondence with the king and his subsequent

conduct fully justify.

Although the proper time had not arrived for throwing

off the mask, Montrose immediately on his return to Scotland, after the

close of this campaign, began to concert measures for counteracting the

designs of the Covenanters; but his plans were embarrassed by some of his

associates disclosing to the Covenanters the existence of an association

which Montrose had formed at Cumbernauld for supporting the royal

authority. A great outcry was raised against Montrose in consequence, but

his influence was so great that the heads of the Covenanters were afraid

to show any severity towards him. On subsequently discovering, however,

that the king had written him letters which were intercepted and forcibly

taken from the messenger, a servant of the Earl of Traquair, they

apprehended him, along with Lord Napier of Merchiston, and Sir George

Stirling of Keith, his relatives and intimate friends, and imprisoned them

in the castle of Edinburgh. On the meeting of the parliament at Edinburgh

in July, 1641, which was attended by the king in person, Montrose demanded

to be tried before them, but his application was rejected by the

Covenanters, who obtained an order from the parliament prohibiting him

from going into the king’s presence. After the king had returned to

England, Montrose and his fellow-prisoners were liberated, and he,

thereupon, went to his own castle, where he remained for some time,

ruminating on the course he should pursue for the relief of the king. The

king, while in Scotland at this time, conferred honours upon several of

the covenanting leaders, apparently for the purpose of conciliation,

Argyle being raised to the dignity of a marquis.

Although Charles complied with the demands of his

Scottish subjects, and heaped many favours and distinctions upon the heads

of the leading Covenanters, they were by no means satisfied, and entered

fully into the hostile views of their brethren in the south, with whom

they made common cause. Having resolved to send an army into England to

join the forces of the parliament, which had come to an open rupture with

the sovereign, they attempted to gain over Montrose to their side by

offering him the post of lieutenant-general of their army, and promising

to accede to any demands he might make; but he rejected all their offers;

and, as an important crisis was at hand, he hastened to England in the

early part of the year 1643, in company with Lord Ogilvie, to lay the

state of affairs before the king, and to offer him his advice and service

in such an emergency. Charles, however, either from a want of confidence

in the judgment of Montrose, who, to the rashness and impetuosity of

youth, added, as he was led to believe, a desire of gratifying his

personal feelings and vanity, or overcome by the calculating but fatal

policy of the Marquis of Hamilton, who deprecated a fresh war between the

king and his Scottish subjects, declined to follow the advice of Montrose,

who had offered to raise an army immediately in Scotland to support him.

A convention of estates called by the Covenanters,

without any authority from the king, met at Edinburgh on the 22d of June,

1643, and he soon perceived from the character and proceedings of this

assembly, the great majority of which were Covenanters, the mistake he had

committed in rejecting the advice of Montrose, and he now resolved,

thenceforth, to be guided in his plans for subduing Scotland by the

opinion of that nobleman. Accordingly, at a meeting held at Oxford,

between the king and Montrose, in the month of December, 1643, when the

Scots army was about entering England, it was agreed that the Earl of

Antrim, an Irish nobleman of great power and influence, who then lived at

Oxford, should be sent to Ireland to raise auxiliaries with whom he should

make a descent on the west parts of Scotland in the month of April

following ;— that the Marquis of Newcastle, who commanded the royal

forces in the north of England, should furnish Montrose with a party of

horse, with which he should enter the south of Scotland, —that an

application should be made to the King of Denmark for some troops of

German horse; and that a quantity of arms should be transported into

Scotland from abroad.

Instructions having been given to the Earl of Antrim to

raise the Irish levy, and Sir James Cochran having been despatched to the

continent as ambassador for the king, to procure foreign aid, Montrose

left Oxford on his way to Scotland, taking York and Durham in his route.

Near the latter city he had an interview with the Marquis of Newcastle for

the purpose of obtaining a sufficient party of horse to escort him into

Scotland, but all he could procure was about 100 horse, badly appointed,

with two small brass field pieces. The Marquis sent orders to

the king’s officers, and to the captains of the militia in Cumberland

and Westmoreland, to afford Montrose such assistance as they could, and he

was in consequence joined on his way to Carlisle by 800 foot and three

troops of horse, of Cumberland and Northumberland militia. With this small

force, and about 200 horse, consisting of noblemen and gentlemen who had

served as officers in Germany, France, or England, Montrose entered

Scotland on the 13th of April, 1644. He had not, however, proceeded far,

when a revolt broke out among the English soldiers, who immediately

returned to England. In spite of this discouragement, Montrose proceeded

on with his small party of horse towards Dumfries, which surrendered to

him without opposition. After waiting there a few lays, in expectation of

hearing some tidings respecting the Earl of Antrim’s movements, without

receiving any, he retired to Carlisle, to avoid being surprised by the

Covenanters, large bodies of whom were hovering about in all directions.

To aid the views of Montrose, the king had appointed

the Marquis of Huntly, on whose fidelity he could rely, his

lieutenant-general in the north of Scotland. He, on hearing of the capture

of Dumfries by Montrose, immediately collected a considerable body of

horse and foot, consisting of Highlanders and lowlanders, at Kincardine-O’Neil,

with the intention of crossing the Cairn-a-Mount; but being disappointed

in not being joined by some forces from Perthshire, Angus, and the Mearns,

which he expected, he altered his steps, and proceeded towards Aberdeen,

which he took. Thence he despatched parties of his troops through the

counties of Aberdeen and Bang, which brought in quantities of horses and

arms for the use of his army. One party, consisting of 120 horse and 300

foot, commanded by the young laird of Drum and his brother, young Gicht,

Colonel Nathaniel Gordon and Colonel Donald Farquharson and others,

proceeded to the town of Montrose, which they took, killed one of the

bailies, made the provost prisoner, and threw some cannon into the sea as

they could not carry them away. But, on hearing that the Earl of Kinghorn

was advancing upon them with the forces of Angus, they made a speedy

retreat, leaving thirty of their foot behind them prisoners. To protect

themselves against the army of the Marquis of Huntly, the inhabitants of

Moray, on the north of the Spey, raised a regiment of foot and three

companies of horse, which were quartered in the town of Elgin.

When the convention heard of Huntly’s movements, they

appointed the Marquis of Argyle to raise an army to quell this

insurrection. He, accordingly, assembled at Perth a force of 5,000 foot

and 800 horse out of Fife, Angus, Mearns, Argyle, and Perthshire with

which he advanced on Aberdeen. Huntly hearing of his approach, fled from

Aberdeen and retired to the town of Banff, where, on the day of his

arrival, he disbanded his army The marquis himself thereafter retired to

Strathnaver, and took up his residence with the master of Reay. Argyle,

after taking possession of Aberdeen, proceeded northward and took the

castles of Gicht and Kellie, made the lairds of Gicht and Haddo prisoners

and sent them to Edinburgh, the latter being, along with one Captain

Logan, afterwards beheaded.

We now return to Montrose, who, after an ineffectual

attempt to obtain an accession of force from the army of Prince Rupert,

Count Palatine of the Rhine, determined on again entering Scotland with

his little band. But being desirous to learn the exact situation of

affairs there, before putting this resolution into effect, he sent Lord

Ogilvie and Sir William Rollock into Scotland, in disguise, for that

purpose. They returned in about fourteen days, and brought a spiritless

and melancholy account of the state of matters in the north, where they

found all the passes, towns, and forts, in possession of the Covenanters,

and where no man dared to speak in favour of the king. This intelligence

was received with dismay by Montrose’s followers, who now began to think

of the best means of securing their own safety. In this unpleasant

conjuncture of affairs, Montrose called them together to consult on the

line of conduct they should pursue. Some advised him to return to Oxford

and inform his majesty of the hopeless state of his affairs in Scotland,

while others gave an opinion that he should resign his corn-mission, and

go abroad till a more favourable opportunity occurred of serving the king;

but the chivalrous and undaunted spirit of Montrose disdained to follow

either of these courses, and he resolved upon the desperate expedient of

venturing into the very heart of Scotland, with only one or two

companions, in the hope of being able to rally round his person a force

sufficient to support the declining interests of his sovereign.

Having communicated this intention privately to Lord

Ogilvie, he put under his charge the few gentlemen who had remained

faithful to him, that he might conduct them to the king; and having

accompanied them to a distance; he withdrew from them clandestinely,

leaving his servants, horses, and baggage behind him, and returned to

Carlisle. Having prepared himself for his journey, he selected Sir William

Rollock, a gentleman of tried honour, and one Sibbald, to accompany him.

Disguised as a groom, and riding upon a lean, worn-out horse, and leading

another in his hand, Montrose passed for Sibbald’s servant, in which

condition and capacity he proceeded to the borders. The party had not

proceeded far when an occurrence took place, which considerably

disconcerted them. Meeting with a Scottish soldier, who had served under

the Marquis of Newcastle in England, he, after passing Rollock and Sibbald,

went up to the marquis, and accosted him by his name. Montrose told him

that he was quite mistaken; but the soldier being positive, and judging

that the marquis was concerned in some important affair, replied, with a

countenance which betokened a kind heart, "Do not I know my lord

Marquis of Montrose well enough But go your way, and God be with

you." When Montrose saw that he could not preserve an

incognito from the penetrating eye of the soldier, he gave him some money

and dismissed him.

This occurrence excited alarm in the mind of Montrose,

and made him accelerate his journey. Within four days he arrived at the

house of Tullibelton, among the hills near the Tay, which belonged to

Patrick Graham of Inchbrakie, his cousin, and a royalist. No situation was

better fitted for concocting his plans, and for communicating with those

clans and the gentry of the adjoining lowlands who stood well affected to

the king, It formed, in fact, a centre, or point d’appui to the

royalists of the Highlands and the adjoining lowlands, from which a pretty

regular communication could be kept up, without any of those dangers which

would have arisen in the lowlands.

For some days Montrose did not venture to appear among

the people in the neighbourhood, nor did he consider himself safe even in

Tullibelton house, but passed the night in an obscure cottage, and in the

day-time wandered alone among the neighbouring mountains, ruminating over

the strange peculiarity of his situation, and waiting the return of his

fellow-travellers, whom he had despatched to collect intelligence on the

state of the kingdom. These messengers came back to him after some days’

absence, bringing with them the most cheerless accounts of the situation

of the country, and of the persecutions which the royalists suffered at

the hands of the Covenanters. Among other distressing pieces of

intelligence they communicated to Montrose the premature and unsuccessful

attempt of the Marquis of Huntly in favour of the royal cause, and of his

retreat to Strathnaver to avoid the fury of his enemies. These accounts

greatly affected Montrose, who was grieved to find that the Gordons, who

were stem royalists, should be exposed, by the abandonment of their chief,

to the revenge of their enemies; but he consoled himself with the

reflection, that as soon as he should be enabled to unfurl the royal

standard, the tide of fortune would turn.

While cogitating on the course he should pursue in this

conjuncture, a report reached him from some shepherds on the hills that a

body of Irish troops had landed in the West, and was advancing through the

Highlands. Montrose at once concluded that these were the auxiliaries whom

the Earl of Antrim had undertaken to send him four months before, and such

they proved to be. This force, which amounted to 1,500 men, was under the

command of Alexander Macdonald, son of Coll Mac-Gillespie Macdonald of

Iona, who had been greatly persecuted by the family of Argyle. Macdonald

had arrived early in July, 1644, among the Hebrides, and had landed and

taken the castles of Meigray and Kinloch Alan. He had then disembarked his

forces in Knoydart, where he expected to be joined by the Marquis of

Huntly and the Earl of Seaforth. As he advanced into the interior, he

despatched the fiery cross for the purpose of summoning the clans to his

standard; but, although the cross was carried through a large extent of