|

As the Privy Council showed

no inclination to decide the questions submitted to them by the Earl of

Caithness and his adversaries, the earl sent his brother, Sir John

Sinclair of Greenland, to Edinburgh, to complain of the delay which had

taken place, and desired him to throw out hints, that if the earl did not

obtain satisfaction for his supposed injuries, he would take redress at

his own hands. The earl thought that he would succeed, by such a threat,

in moving the council to decide in his favour, for he was well aware that

he was unable to carry it into execution. To give some appearance of an

intention to enforce it, he, in the month of October, 1613, while the Earl

of Sutherland, his brothers and nephews, were absent from the country,

made a demonstration of invading Sutherland or Strathnaver, by collecting

his forces at a particular point, and bringing thither some pieces of

ordnance from Castle Sinclair. The Earl of Sutherland, having arrived in

Sutherland while the Earl of Caithness was thus employed, immediately

assembled some of his countrymen, and, along with his brother Sir

Alexander, went to the marches between Sutherland and Caithness, near the

height of Strathully, where they waited the approach of the Earl of

Caithness. here they were joined by Mackay, who had given notice of the

Earl of Caithness’s movements to the lairds of Foulis, Balnagown, and

Assynt, the sheriff of Cromarty, and the tutor of Kintail, all of whom

prepared themselves to assist the Earl of Sutherland. The Earl of

Caithness, however, by advice of his brother, Sir John Sinclair, returned

home and disbanded his force.

To prevent the Earl of

Caithness from attempting any farther interference with the Privy Council,

either in the way of intrigue or intimidation, Sir Robert Gordon obtained

a remission and pardon from the king, in the month of December, 1613, to

his nephew, Donald Mackay, John Gordon, younger of Embo, John Gordon in

Broray, Adam Gordon Georgeson, and their accomplices, for the slaughter of

John Sinclair of Stirkage at Thurso. However, Sir Gideon Murray, Deputy

Treasurer for Scotland, contrived to prevent the pardon passing through

the seals till the beginning of the year 1616.

The Earl of Caithness,

being thus baffled in his designs against the Earl of Sutherland and his

friends, fell upon a device which never failed to succeed in times of

religious intolerance and persecution. Unfortunately for mankind and for

the interests of Christianity, the principles of religious toleration,

involving the inalienable right of every man to worship God according to

the dictates of his conscience, have been till of late but little

understood, and at the period in question, and for upwards of one hundred

and sixty years thereafter, the statute book of Scotland was disgraced by

penal enactments against the Catholics, almost unparalleled for their

sanguinary atrocity. By an act of the first parliament of James VI., any

Catholic who assisted at the offices of his religion was, "for the

first fault," that is, for following the dictates of his conscience,

to suffer confiscation of all his goods, movable and immovable, personal

and real; for the second, banishment; and death for the third fault! But

the law was not confined to overt acts only—the mere suspicion of being

a Catholic placed the suspected person out of the pale and protection of

the law; for if, on being warned by the bishops and ministers, he did not

recant and give confession of his faith according to the approved form, he

was excommunicated, and declared infamous and incapable to sit or stand in

judgment, pursue or bear office.

Under this last-mentioned

law the Earl of Caithness now sought to gratify his vengeance against the

Earl of Sutherland. Having represented to the Archbishop of St. Andrews

and the clergy of Scotland that the Earl of Sutherland was at heart a

Catholic, he prevailed upon the bishops—with little difficulty, it is

supposed—to acquaint the king thereof. His majesty thereupon issued a

warrant against the Earl of Sutherland, who was in consequence apprehended

and imprisoned at St. Andrews. The earl applied to the bishops for a month’s

delay, till the 15th February, 1614, promising that before that time he

would either give the church satisfaction or surrender himself; but his

application was refused by the high commission of Scotland. Sir Alexander

Gordon, the brother of the earl, being then in Edinburgh, immediately gave

notice to his brother, Sir Robert Gordon, who was at the time in London,

of the proceedings against their brother, the earl. Sir Robert having

applied to his majesty for the release of the earl for a time, that he

might make up his mind on the subject of religion, and look after his

affairs in the north, his majesty granted a warrant for his liberation

till the month of August following. On the expiration of the time, he

returned to his confinement at St. Andrews, from which he was removed, on

his own application, to the abbey of Holyrood house, where he remained

till the month of March, 1615, when he obtained leave to go home,

"having," says Sir Robert Gordon, "in some measure

satisfied the church concerning his religion."

The Earl of Caithness, thus

again defeated in his views, tried, as a dernier resort, to disjoin

the families of Sutherland and Mackay. Sometimes he attempted to prevail

upon the Marquis of Huntly to persuade the Earl of Sutherland and his

brothers to come to an arrangement altogether independent of Mackay; and

at other times he endeavoured to persuade Mackay, by holding out certain

inducements to him, to compromise their differences without including the

Earl of Sutherland in the arrangement; but he completely failed in these

attempts.

In 1614—15 a formidable rebellion broke

out in the South Hebrides, arising from the efforts made by the clan

Donald of Islay to retain that island in their possession. The castle of

Dunyveg in Islay, which, for three years previous to 1614, had been in

possession of the Bishop of the Isles, having been taken by Angus Oig,

younger brother of Sir James Macdonald of Islay, from Ranald Oig, who had

surprised it, the former refused to restore it to the bishop. The Privy

Council took the matter in hand, and, having accepted from John Campbell

of Calder an offer of a feu-duty or perpetual rent for Islay, they

prevailed on him to accept a commission against Angus Oig and his

followers. The clan Donald, who viewed with suspicion the growing power of

the Campbells, looked upon this project with much dislike, and treated

certain hostages left by the bishop with great severity. Even the bishop

remonstrated against making "the name of Campbell greater in the

Isles than they are already," thinking it neither good nor profitable

to his majesty, "to root out one pestiferous clan, and plant in

another little better." The remonstrance of the bishop and an offer

made to put matters right by Sir James Macdonald, who was then imprisoned

in Edinburgh castle, were alike unheeded, and Campbell of Calder received

his commission of Lieutenandry against Angus Oig Macdonald, Coll

Mac-Gillespie, and the other rebels of Islay. A free pardon was offered to

all who were not concerned in the taking of the castle, and a remission to

Angus Oig, provided he gave up the castle, the hostages, and two

associates of his own rank.

While Campbell was

collecting his forces, and certain auxiliary troops from Ireland were

preparing to embark, the chancellor of Scotland, the Earl of Dunfermline,

by means of a Ross-shire man, named George Graham of Eryne, prevailed on

Angus Oig to release the bishop’s hostages, and deliver up to Graham the

castle, in behalf of the chancellor. Graham re-delivered the castle to

Angus, to be held by him as the regular constable, until he should receive

further orders from the chancellor, and at the same time assured Angus of

the chancelior’s countenance and protection, enjoining him to resist all

efforts on the part of Campbell or his friends to eject him. These

injunctions Graham’s dupes too readily followed. "There can be no

doubt whatever that the chancellor was the author of this notable plan to

procure the liberation of the hostages, and at the same time to deprive

the clan Donald of the benefit of the pardon promised to them on this

account. There are grounds for a suspicion that the chancellor himself

desired to obtain Islay; although it is probable that he wished to avoid

the odium attendant on the more violent measures required to render such

an acquisition available. He, therefore, contrived so as to leave the

punishment of the clan Donald to the Campbells, who were already

sufficiently obnoxious to the western clans, whilst he himself had the

credit of procuring the liberation of the hostages."

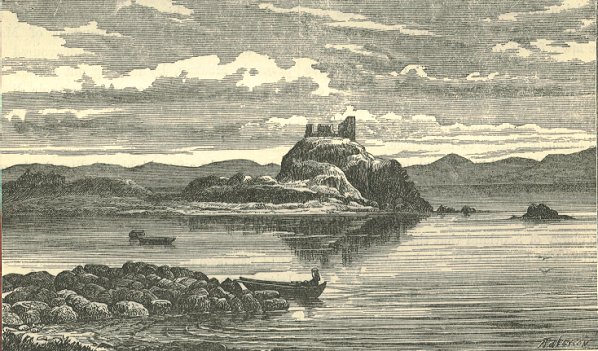

Dunyveg Castle, Islay

Campbell of Calder and Sir

Oliver Lambert, commander of the Irish forces, did not effect a junction

till the 5th of January, 1615, and on the 6th, Campbell landed on Islay

with 200 men, his force being augmented next day by 140 more. Several of

the rebels, alarmed, deserted Angus, and were pardoned on condition of

helping the besiegers. Ronald Mac-James, uncle of Angus Oig, surrendered a

fort on the island of Lochgorme which he commanded, on the 21st, and along

with his son received a conditional assurance of his majesty’s favour.

Operations were commenced against Dunyveg on February 1st, and shortly

after Angus had an interview with the lieutenant, during which the latter

showed that Angus had been deceived by Graham, upon which he promised to

surrender. On returning to the castle, however, he refused to implement

his promise, being instigated to hold out apparently by Coil MacGillespie.

After being again battered for some time, Angus and some of his followers

at last surrendered unconditionally, Coil Mac-Gillespie contriving to make

his escape. Campbell took possession of the castle on the 3d February,

dispersed the forces of the rebels, and put to death a number of those who

had deserted the siege; Angus himself was reserved for examination by the

Privy Council. In the course of the examination it came out clearly that

the Earl of Argyle was the original promoter of the seizure of the castle,

his purpose apparently being to ruin the clan Donald by urging them to

rebellion; but this charge, as well as that against the Earl of

Dunfermline, appears to have been smothered.

During the early part of

the year 1615, Coil Mac-Gillespie and others of the clan Donald who had

escaped, infested the western coasts, and committed many acts of piracy,

being joined about the month of May by Sir James Macdonald, who had

escaped from Edinburgh castle, where he had been lying for a long time

under sentence of death. Sir James and his followers, now numbering

several hundreds, after laying in a good supply of provisions, sailed

towards Islay. The Privy Council were not slow in taking steps to repress

the rebellion, although various circumstances occurred to thwart their

intentions. Calder engaged to keep the castle of Dunyveg against the

rebels, and instructions were given to the various western gentlemen

friendly to the government to defend the western coasts and islands. Large

rewards were offered for the principal rebels. All the forces were

enjoined to be at their appointed stations by the 6th of July, furnished

with forty days’ provisions, and with a sufficient number of boats, to

enable them to act by sea, if necessary.

Sir James Macdonald, about

the end of June, landing on Islay, managed by stratagem to obtain

possession of Dunyveg Castle, himself and his followers appearing to have

conducted themselves with great moderation. Dividing his force, which

numbered about 400, into two bodies, with one of which he himself intended

to proceed to Jura, the other, under Coil Mac-Gillespie, was destined for

Kintyre, for the purpose of encouraging the ancient followers of his

family to assist him. In the beginning of July, Angus Oig and a number of

his followers were tried and condemned, and executed immediately after.

Various disheartening

reports were now circulated as to the disaffection of Donald Gorme of

Sleat, captain of the clan Ranald, Ruari Macleod of Harris, and others;

and that Hector Maclean of Dowart, if not actually engaged in the

rebellion, had announced, that if he was desired to proceed against the

clan Donald, he would not be very earnest in the service. The militia of

Ayr, Renfrew, Dumbarton, Bute, and Inverness were called out, and a

commission was granted to the Marquis of Hamilton to keep the clan Donald

out of Arran.

The Privy Council had some time before this

urged the king to send down the Earl of Argyle from England—to which he

had fled from his numerous creditors—to act as lieutenant in suppressing

the insurrection. After many delays, Argyle, to whom full powers had been

given to act as lieutenant, at length mustered his forces at Duntroon on

Loch Crinan early in September. He issued a proclamation of pardon to all

rebels who were willing to submit, and by means of spies examined

Macdonald’s camp, which had been pitched on the west coast of Kintyre,

the number of the rebels being ascertained to be about 1,000 men. Argyle

set himself so promptly and vigorously to crush the rebels, that Sir James

Macdonald, who had been followed to Islay by the former, finding it

impossible either to resist the Lieutenant’s forces, or to escape with

his galleys to the north isles, desired from the earl a truce of four

days, promising at the end of that time to surrender. Argyle would not

accede to this request except on condition of Sir James giving up the two

forts which he held; this Sir James urged Coil Mac-Gillespie to do, but he

refused, although he sent secretly to Argyle a message that he was willing

to comply with the earl’s request. Argyle immediately sent a force

against Sir James to surprise him, who, being warned of this by the

natives, managed to make his escape to an island called Inchdaholl, on the

coast of Ireland, and never again returned to the Hebrides. Next day,

Mac-Gillespie surrendered the two forts and his prisoners, upon assurance

of his own life and the lives of a few of his followers, at the same time

treacherously apprehending and delivering to Argyle, Macfie of Colonsay,

one of the principal rebel leaders, and eighteen others. This conduct soon

had many imitators, including Macfie himself.

Having delivered the forts in Islay to

Campbell of Calder, and having executed a number of the leading rebels,

Argyle proceeded to Kintyre, and crushed out all remaining seeds of

insurrection there. Many of the principal rebels, notwithstanding a

diligent search, effected their escape, many of them to Ireland, Sir James

Macdonald being sent to Spain by some Jesuits in Galway. The escape of so

many of the principal rebels seems to have given the Council great

dissatisfaction. Argyle carried on operations till the middle of December

1615, refusing to dismiss the hired soldiers in the beginning of November,

as he was ordered by the Council to do. He was compelled to disburse the

pay, amounting to upwards of £7,000, for the extra month and a half out

of his own pocket.

"Thus," to use

the words of our authority for the above details, "terminated

the last struggle of the once powerful clan Donald of Islay and Kintyre,

to retain, from the grasp of the Campbells, these ancient possessions of

their tribe."

Ever since the death of

John Sinclair at Thurso, the Earl of Caithness used every means in his

power to induce such of his countrymen as were daring enough, to show

their prowess and dexterity, by making incursions into Sutherland or

Strathnaver, for the purpose of annoying the vassals and dependants of the

Earl of Sutherland and his ally, Mackay. Amongst others he often

communicated on this subject with William Kennethson, whose father,

Kenneth Buidhe, had always been the principal instrument in the hands of

Earl George in oppressing the people of his own country. For the

furtherance of his plans he at last prevailed upon William, who already

stood rebel to the king in a criminal cause, to go into voluntary

banishment into Strathnaver, and put himself under the protection, of

Mackay, to whom he was to pretend that he had left Caithness to avoid any

solicitations from the Earl of Caithness to injure the inhabitants of

Strathnaver. To cover their designs they caused a report to be spread that

William Mac-Kenneth was to leave Caithness because he would not obey the

orders of the earl to execute some designs against Sir Robert Gordon, the

tutor of Sutherland, and Mackay, and when this false rumour had been

sufficiently spread, Mac-Kenneth, and his brother John, and their

dependants, fled into Strathnaver and solicited the favour and protection

of Mackay. The latter received them kindly; but as William and his party

had been long addicted to robbery and theft, he strongly advised them to

abstain from such practices in all time coming; and that they might not

afterwards plead necessity as an excuse for continuing their depredations,

he allotted them some lands to dwell on. After staying a month or two in

Strathnaver, during which time they stole some cattle and horses out of

Caithness, William received a private visit by night from Kenneth Buidhe,

his father, who had been sent by the Earl of Caithness for the purpose of

executing a contemplated depredation in Sutherland. Mackay was then in

Sutherland on a visit to his uncle, Sir Robert Gordon, which being known

to William Mac-Kenneth, he resolved to enter Sutherland with his party,

and carry off into Caithness all the booty they could collect. Being

observed in the glen of Loth by some of the clan Gun, collecting cattle

and horses, they were immediately apprehended, with the exception of

Iain-Garbh-Mac-Chonald-Mac-Mhurchidh-Mhoir, who, being a very resolute

man, refused to surrender, and was in consequence killed. The prisoners

were delivered to Sir Robert Gordon at Dornoch, who committed William and

his brother John to the castle of Dornoch for trial. In the meantime two

of the principal men of Mac-Kenneth’s party were tried, convicted, and

executed, and the remainder were allowed to return home on giving surety

to keep the peace. This occurrence took place in the month of January

1616.

The Earl of Caithness now finished his

restless career of iniquity by the perpetration of a crime which, though

trivial in its consequences, was of so highly a penal nature in itself as

to bring his own life into jeopardy. As the circumstances which led to the

burning of the corn of William Innes, a servant of Lord Forbes at Sanset

in Caithness, and the discovery of the Earl of Caithness as instigator,

are somewhat curious, it is thought that a recital of them may not be here

out of place.

Among other persons who had

suffered at the hands of the earl was his own kinsman, William Sinclair of

Dumbaith. After annoying him in a variety of ways, the earl instigated his

bastard brother, Henry Sinclair, and Kenneth Buidhe, to destroy and lay

waste part of Dumbaith’s lands, who, unable to resist, and being in

dread of personal risk, locked himself up in his house at Dunray, which

they besieged. William Sinclair immediately applied to John, Earl of

Sutherland, for assistance, who sent his friend Mackay with a party to

rescue Sinclair from his perilous situation. Mackay succeeded, and carried

Sinclair along with him into Sutherland, where he remained for a time, but

he afterwards went to reside in Moray, where he died. Although thus

cruelly persecuted and forced to become an exile from his country by the

Earl of Caithness, no entreaties could induce him to apply for redress,

choosing rather to suffer himself than to see his relative punished.

William Sinclair was succeeded by his grandson, George Sinclair, who

married a sister of Lord Forbes. By the persuasion of his wife, who was a

mere tool in the hands of the Earl of Caithness, George Sinclair was

induced to execute a deed of entail, by which, failing of heirs male of

his own body, he left the whole of his lands to the earl. When the earl

had obtained this deed he began to devise means to make away with

Sinclair, and actually persuaded Sinclair’s wife to assist him in this

nefarious design. Having obtained notice of this conspiracy against his

life, Sinclair left Caithness and took up his residence with his

brother-in-law, Lord Forbes, who received him with great kindness and

hospitality, and reprobated very strongly the wicked conduct of his

sister. Sinclair now recalled the entail in favour of the Earl of

Caithness, and made a new deed by which he conveyed his whole estate to

Lord Forbes. George Sinclair died soon after the execution of the deed,

and having left no issue, Lord Forbes took possession of his lands of

Dunray and Dumbaith.

Disappointed in his plans

to acquire Sinclair’s property, the Earl of Caithness seized every

opportunity of annoying Lord Forbes in his possessions, by oppressing his

tenants and servants, in every possible way, under the pretence of

discharging his duty as sheriff, to which office he had been appointed by

the Earl of Huntly, on occasion of his marriage with Huntly’s sister.

Complaints were made from time to time against the earl, on account of

these proceedings, to the Privy Council of Scotland, which, in some

measure, afforded redress; but to protect his tenants more effectually,

Lord Forbes took up a temporary residence in Caithness, relying upon the

aid of the house of Sutherland in. ease of need.

As the Earl of Caithness was aware that any

direct attack on Lord Forbes would be properly resented, and as any

enterprise undertaken by his own people would be laid to his charge,

however cautions he might be in dealing with them, he fixed on the clan

Gun as the fittest instruments for effecting his designs against Lord

Forbes. Besides being the most resolute men in Caithness, always ready to

undertake any desperate action, they depended more upon the Earl of

Sutherland and Mackay, from whom they held some lands, than upon the Earl

of Caithness; a circumstance which the latter supposed, should the

contemplated outrages of the clan Gun ever become matter of inquiry, might

throw the suspicion upon the two former as the silent instigators.

Accordingly, the earl opened a negotiation with John Gun, chief of the

clan Gun in Caithness, and with his brother, Alexander Gun, whose father

he had hanged in the year 1586. In consequence of an invitation, the two

brothers, along with Alexander Gun, their cousin-gennan, repaired to

Castle Sinclair, where they met the earl. The earl did not at first

divulge his plans to all the party; but taking Alexander Gun, the cousin,

aside, he pointed out to him the injury he alleged he had sustained, in

consequence of Lord Forbes having obtained a footing in Caithness,—that

he could no longer submit to the indignity shown him by a stranger,—that

he had made choice of him (Gun) to undertake a piece of service for him,

on performing which he would reward him most amply; and to secure

compliance, the earl desired him to remember the many favours he had

already received from him, and how well he had treated him, promising, at

the same time, to show him even greater kindness in time coming. Alexander

thereupon promised to serve the earl, though at the hazard of his life;

but upon being interrogated by the earl whether he would undertake to burn

the corn of Sanset, belonging to William Innes, a servant of Lord Forbes,

Gun, who had never imagined that he was to be employed in such an ignoble

affair, expressed the greatest astonishment at the proposal, and refused,

in the most peremptory and indignant manner, to undertake its execution;

yet, to satisfy the earl, he told him that he would, at his command,

undertake to assassinate William Innes,—an action which he considered

less criminal and dishonourable, and more becoming a gentleman, than

burning a quantity of corn! Finding him obdurate, the earl enjoined him to

secrecy.

The earl next applied to

the two brothers, John and Alexander, with whom he did not find it so

difficult to treat. They at first hesitated with some firmness in

undertaking the business on which the earl was so intent; and they pleaded

an excuse, by saying, that as justice was then more strictly executed in

Scotland than formerly, they could not expect to escape, as they had no

place of safety to retreat to after the crime was committed; as a proof of

which they instanced the cases of the clan Donald and the clan Gregor, two

races of people much more powerful than the clan Gun, who had been brought

to the brink of ruin, and almost annihilated, under the authority of the

laws. The earl replied, that as soon as they should perform the service

for him he would send them to the western isles, to some of his

acquaintances and friends, with whom they might remain till Lord Forbes

and he were reconciled, when he would obtain their pardon; that in the

meantime he would profess, in public, to be their enemy, but that he would

be their friend secretly, and permit them to frequent Caithness without

danger. Alexander Gun, overcome at last by the entreaties of the earl,

reluctantly consented to his request, and going into Sanset, in the dead

of night, with two accomplices, set fire to all the corn stacks which were

in the barn-yard, belonging to William Innes, and which were in

consequence consumed. This affair occurred in the month of November, 1615.

The Earl of Caithness immediately spread a report through the whole

country that Mackay’s tenants had committed this outrage, but the

deception was of short duration.

It may be here noticed that

John, sixth Earl of Sutherland, died in September, 1615, and was succeeded

by his eldest son, John, a boy six years old, to whom Sir Robert Gordon,

his uncle, was appointed tutor.

Sir Robert Gordon, having

arrived in the north of Scotland, from England, in the month of December

following, resolved to probe the matter to the bottom, not merely on

account of his nephew, Mackay, whose men were suspected, but to satisfy

Lord Forbes, who was now on friendly terms with the house of Sutherland ;

but the discovery of the perpetrators soon became an easy task, in

consequence of a quarrel among the clan Gun themselves, the members of

which upbraided one another as the authors of the fire-raising. Alexander

Gun, the cousin of Alexander Gun, the real criminal, thereupon fled from

Caithness, and sent some of his friends to Sir Robert Gordon and Donald

Mackay with these proposals :—that if they would receive him into favour,

and secure him from danger, he would confess the whole circumstances, and

reveal the authors of the conflagration, and that he would declare the

whole before the Privy Council if required. On receiving this proposal,

Sir Robert Gordon appointed Alexander Gun to meet him privately at

Helmsdale, in the house of Sir Alexander Gordon, brother of Sir Robert. A

meeting was accordingly held at the place appointed, at which Sir Robert

and his friends agreed to do everything in their power to preserve Gun’s

life; and Mackay promised, moreover, to give him a possession in Strathie,

where his father had formerly lived.

When the Earl of Caithness heard of

Alexander Gun’s flight into Sutherland he became greatly alarmed lest

Alexander should reveal the affair of Sanset; and anticipating such a

result, the earl gave out everywhere that Sir Robert Gordon, Mackay, and

Sir Alexander Gordon, had hired some of the clan Gun to accuse him of

having burnt William Innes’s corn. But this artifice was of no avail,

for as soon as Lord Forbes received notice from Sir Robert Gordon of the

circumstances related by Alexander Gun, he immediately cited John Gun and

his brother Alexander, and their accomplices, to appear for trial at

Edinburgh, on the 2d April, 1616, to answer to the charge of burning the

corn at Sanset; and he also summoned the Earl of Caithness, as sheriff of

that county, to deliver them up for trial. John Gun, thinking that the

best course he could pursue under present circumstances was to follow the

example of his cousin, Alexander, sent a message to Sir Alexander Gordon,

desiring an interview with him, which being granted, they met at Navidale.

John Gun then offered to reveal everything he knew concerning the fire, on

condition that his life should be spared; but Sir Alexander observed that

he could come under no engagement, as he was uncertain how the king and

the council might view such a proceeding; but he promised, that as John

had not been an actor in the business, but a witness only to the

arrangement between his brother and the Earl of Caithness, he would do

what he could to save him, if he went to Edinburgh in compliance with the

summons.

In this state of matters,

the Earl of Caithness wrote to the Marquis of Huntly, accusing Sir Robert

Gordon and Mackay of a design to bring him within the reach of the law of

treason, and to injure the honour of his house by slandering him with the

burning of the corn at Sanset. The other party told the marquis that they

could not refuse to assist Lord Forbes in finding out the persons who had

burned the corn at Sanset, but that they had never imagined that the earl

would have acted so base a part as to become an accomplice in such a

criminal act; and farther, that as Mackay’s men were challenged with the

deed, they certainly were entitled at least to clear Mackay’s people

from the charge by endeavouring to find out the malefactors,—in all

which they considered they had done the earl no wrong. The Marquis of

Huntly did not fail to write the Earl of Caithness the answer he had

received from Sir Robert Gordon and Mackay, which grieved him exceedingly,

as he was too well aware of the consequences which would follow if the

prosecution of the Guns was persevered in.

At the time appointed for

the trial of the Guns, Sir Robert Gordon, Mackay, and Lord Forbes, with

all his friends, went to Edinburgh, and upon their arrival they entreated

the council to prevent a remission in favour of the Earl of Caithness from

passing the signet until the affair in hand was tried; a request with

which the council complied. The Earl of Caithness did not appear; but he

sent his son, Lord Berridale, to Edinburgh, along with John Gun and all

those persons who had been summoned by Lord Forbes, with the exception of

Alexander Gun and his two accomplices. He alleged as his reason for not

sending them that they were not his men, being Mackay’s own tenants, and

dwelling in Dilred, the property of Mackay, which was held by him off the

Earl of Sutherland, who, he alleged, was bound to present the three

persons alluded to. But the lords of the council would not admit of this

excuse, and again required Lord Berndale and his father to present the

three culprits before the court on the 10th June following, because,

although they had possessions in Dilred, they had also lands from the Earl

of Caithness on which they usually resided. Besides, the deed was

committed in Caithness, of which the earl was sheriff, on which account

also he was bound to apprehend them. Lord Berndale, whose character was

quite the reverse of that of his father, apprehensive of the consequences

of a trial, now offered satisfaction in his father’s name to Lord Forbes

if he would stop the prosecution; but his lordship refused to do anything

without the previous advice and consent of Sir Robert Gordon and Mackay,

who, upon being consulted, caused articles of agreement to be drawn up,

which were presented to Lord Bernidale by neutral persons for his

acceptance. He, however, considering the conditions sought to be imposed

upon his father too hard, rejected them.

In consequence of the refusal of Lord Berridale to accede to the terms

proposed, John Gun was apprehended by one of the magistrates of Edinburgh,

on the application of Lord Forbes, and committed a prisoner to the jail of

that city. Gun thereupon requested to see Sir Robert Gordon and Mackay,

whom he entreated to use their influence to procure him his liberty,

promising to declare everything he knew of the business for which he was

prosecuted before the lords of the council. Sir Robert Gordon and Mackay

then deliberated with Lord Forbes and Lord Elphinston on the subject, and

they all four promised faithfully to Gun to do everything in their power

to save him, and that they would thenceforth maintain and defend him and

his cousin, Alexander Gun, against the Earl of Caithness or any person, as

long as they had reason and equity on their side; besides which, Mackay

promised him a liferent lease of the lands in Strathie to compensate for

his possessions in Caithness, of which he would, of course, be deprived by

the earl for revealing the latter’s connexion with the fire-raising at

Sanset. John Gun was accordingly examined the following day by the lords

of the council, when he confessed that the Earl of Caithness made his

brother, Alexander Gun, burn the corn of Sanset, and that the affair had

been proposed and discussed in his presence. Alexander Gun, the cousin,

was examined also at the same time, and stated the same circumstances

precisely as John Gun had done. After examination, John and Alexander were

again committed to prison.

As neither the Earl of Caithness nor his son, Lord

Berridale, complied with the commands of the council to deliver up

Alexander Gun and his accomplices in the month of June, they were both

outlawed and denounced rebels; and were summoned and charged by Lord

Forbes to appear personally at Edinburgh in the month of July immediately

following, to answer to the charge of causing the corn of Sanset to be

burnt. This fixed determination on the part of Lord Forbes to bring the

earl and his son to trial had the effect of altering their tone, and they

now earnestly entreated him and Mackay to agree to a reconciliation on any

terms; but they declined to enter into any arrangement until they had

consulted Sir Robert Gordon. After obtaining Sir Robert’s consent, and a

written statement of the conditions which he required from the Earl of

Caithness in behalf of his nephew, the Earl of Sutherland, the parties

entered into a final agreement in the month of july, 1616. The principal

heads of the contract, which was afterwards recorded in the books of

council and session, were as follows :—That all civil actions between

the parties should be settled by the mediation of common friends,— that

the Earl of Caithness and his son should pay to Lord Forbes and Mackay the

sum of 20,000 merks Scots money,—that all quarrels and criminal actions

should be mutually forgiven, and particularly, that the Earl of Caithness

and all his friends should forgive and remit the slaughter at Thurso —that

the Earl of Caithness and his son should renounce for themselves and their

heirs all jurisdiction, criminal or civil, within Sutherland or

Strathnaver, and any other jurisdiction which they should thereafter

happen to acquire over any lands lying within the diocese of Caithness

then pertaining, or which should afterwards belong, to the Earl of

Sutherland, or his heirs, —that the Earl of Caithness should deliver

Alexander Gun and his accomplices to Lord Forbes,—that the earl, his

son, and their heirs, should never thenceforth contend with the Earl of

Sutherland for precedency in parliament or priority of place,—that the

Earl of Caithness and his son, their friends and tenants, should keep the

peace in time coming, under the penalty of great sums of money, and should

never molest nor trouble the tenants of the Earl of Sutherland and Lord

Forbes,----that the Earl of Caithness, his son, or their friends, should

not receive nor harbour any fugitives from Sutherland or Strathnaver,—and

that there should be good friendship and amity kept amongst them in all

time to come.

In consequence of this agreement, the two sons of Kenneth Buy, William

and John before-mentioned, were delivered to Lord Berndale, who gave

security for their keeping the peace; and John Gun and Alexander his

cousin were released, and delivered to Lord Forbes and Mackay, who gave

surety to the lords of the council to present them for trial whenever

required; and as the Earl of Caithness had deprived them of their

possessions in Caithness on account of the discovery they had made,

Mackay, who had lately been knighted by the king, gave them lands in

Strathnaver as he had promised. Matters being thus settled, Lord Berridale

presented himself before the court at Edinburgh to abide his trial; but no

person of course appearing against him, the trial was postponed. The Earl

of Caithness, however, failing to appear, the diet against him was

continued till the 29th of August following.

Although the king was well pleased, on account of the

peace which such an adjustment would produce in his northern dorninions,

with the agreement which had been entered into, and the proceedings which

followed thereon, all of which were made known to him by the Privy

Council; yet, as the passing over such a flagrant act as wilful

fire-raising, without punishment, might prove pernicious, he wrote a

letter to the Privy Council of Scotland, commanding them to prosecute,

with all severity, those who were guilty of, or accessory to, the crime.

Lord Berridale was thereupon apprehended on suspicion, and committed a

prisoner to the castle of Edinburgh; and his father, perceiving the

determination of the king to prosecute the authors of the fire, again

declined to appear for trial on the appointed day, on which account he was

again outlawed, and declared a rebel as the guilty author.

In this extremity Lord Berridale had recourse to Sir

Robert Gordon, then resident at court, for his aid. He wrote him a letter,

entreating him that, as all controversies were now settled, he would, in

place of an enemy become a faithful friend,—that for his own part, he,

Lord Berridale, had been always innocent of the jars and dissensions which

had happened between the two families,—that he was also innocent of the

crime of which he was charged,—and that he wished his majesty to be

informed by Sir Robert of these circumstances, hoping that he would order

him to be released from confinement. Sir Robert answered, that he had long

desired a perfect agreement between the houses of Sutherland and Caithness,

which he would endeavour to maintain during his administration in

Sutherland, — that he would intercede with the king in behalf of his

lordship to the utmost of his power,—that all disputes being now at an

end, he would be his faithful friend,—that he had a very different

opinion of his disposition from that he entertained of his father, the

earl; and he concluded by entreating him to be careful to preserve the

friendship which had been now commenced between them.

As the king understood that Lord Berridale was supposed to be innocent

of the crime with which he and his father stood charged, and as he could

not, without a verdict against Berridale, proceed against the family of

Caithness by forfeiture, in consequence of his lordship having been infeft

many years before in his father’s estate; his majesty, on the earnest

entreaty of the then bishop of Ross, Sir Robert Gordon, and Sir James

Spence of Wormistoun, was pleased to remit and forgive the crime on the

following conditions:—lst. That the Earl of Caithness and his son should

give satisfaction to their creditors, who were constantly annoying his

majesty with clamours against the earl, and craving justice at his hands.

2d. That the Earl of Caithness, with consent of Lord Berridale, should

freely renounce and resign perpetually, into, the hands of his majesty,

the heritable sheriffship and justiciary of Caithness. 3d. That the Earl

of Caithness should deliver the three criminals who had burnt the corn,

that public justice might be satisfied upon them, as a terror and example

to others. 4th. That the Earl of Caithness, with consent of Lord Berridale,

should give and resign in perpetnum to the bishop of Caithness, the

house of Strabister, with as many of the feu lands of that bishopric as

should amount to the yearly value of two thousand merks Scots money, for

the purpose of augmenting the income of the bishop, which was at that time

small in consequence of the greater part of his lands being in the hands

of the earl. Commissioners were sent down from London to Caithness in

October 1616, to see that these conditions were complied with. The second

and last conditions were immediately implemented; and as the earl and his

son promised to give satisfaction to their creditors, and to do everything

in their power to apprehend the burners of the corn, the latter was

released from the castle of Edinburgh, and directions were given for

drawing up a remission and pardon to the Earl of Caithness. Lord Berridale,

however, had scarcely been released from the castle, when he was again

imprisoned within the jail of Edinburgh, at the instance of Sir James Home

of Cowdenknowes, his cousin german, who had become surety for him and his

father to their creditors for large sums of money. The earl himself

narrowly escaped the fate of his son and retired to Caithness, but his

creditors had sufficient interest to prevent his remission from passing

till they should be satisfied. With consent of the creditors the council

of Scotland gave him a personal protection, from time to time, to enable

him to come to Edinburgh for the purpose of settling with them, but he

made no arrangement, and returned privately into Caithness before the

expiration of the supersedere which had been granted him, leaving

his son to suffer all the miseries of a prison. After enduring a captivity

of five years, Lord Berridale was released from prison by the good offices

of the Earl of Enzie, and put, for behoof of himself, and his own and his

father’s creditors, in possession of the family estates from which his

father was driven by Sir Robert Gordon acting under a royal warrant, a

just punishment for the many enormities of a long and misspent life.

Desperate as the fortunes of the Earl of Caithness were

even previous to the disposal of his estates, he most unexpectedly found

an ally in Sir Donald Mackay, who had taken offence at Sir Robert Gordon.

and who, being a man of quick resolution and of an inconstant disposition,

determined to forsake the house of Sutherland, and to ingratiate himself

with the Earl of Caithness. He alleged various causes of discontent as a

reason for his conduct, one of the chief being connected with pecuniary

considerations; for having, as he alleged, burdened his estates with debts

incurred for some years past in following the house of Sutherland, he

thought that, in time coming, he might, by procuring the favour of the

Earl of Caithness, turn the same to his own advantage and that of his

countrymen. Moreover, as he had been induced to his own prejudice to grant

certain life-rent tacks of the lands of Strathie and Dilred to John and

Alexander Gun, and others of the clan Gun for revealing the affair of

Sanset, he thought that by joining the Earl of Caithness, these might be

destroyed, by which means he would get back his lands which he meant to

convey to his brother, John Mackay, as a portion; and he, moreover,

expected that the earl would give him and his countrymen some possessions

in Caithness. But the chief ground of discontent on the part of Sir Donald

Mackay was an action brought against him and Lord Forbes before the court

of session, to recover a contract entered into between the last Earl of

Sutherland and Mackay, in the year 1613, relative to their marches and

other matters of controversy, which being considered by Mackay as

prejudicial to him, he had endeavoured to get destroyed through the agency

of some persons about Lord Forbes, into whose keeping the deed had been

intrusted.

After brooding over these subjects of discontent for

some years, Mackay, in the year 1618, suddenly resolved to break with the

house of Sutherland, and to form an alliance with the Earl of Caithness,

who had long borne a mortal enmity at that family. Accordingly, Mackay

sent John Sutherland, his cousin-german, into Caithness to request a

private conference with the earl in any part of Caithness he might

appoint. This offer was too tempting to be rejected by the earl, who

expected, by a reconciliation with Sir Donald Mackay, to turn the same to

his own personal gratification and advantage. In the first place, he hoped

to revenge himself upon the clan Gun, who were his principal enemies, and

upon Sir Donald himself by detaching him from his superior, the Earl of

Sutherland, and from the friendship of his uncles, who had always

supported him in all his difficulties. In the second place, he expected

that, by alienating Mackay from the duty and affection he owed the house

of Sutherland, that he would weaken his power and influence. And lastly,

he trusted that Mackay would not only be prevailed upon to discharge his

own part, but would also persuade Lord Forbes to discharge his share of

the sum of 20,000 merks Scots, which he and his son, Lord Berridale, had

become bound to pay them, on account of the burning at Sanset.

The Earl of Caithness having at once agreed to Mackay’s proposal, a

meeting was held by appointment in the neighbourhood of Dunray, in the

parish of Reay, in Caithness. The parties met in the night-time,

accompanied each by three men only. After much discussion, and various

conferences, which were continued for two or three days, they resolved to

destroy the clan Gun, and particularly John Gun, and Alexander his cousin.

To please the earl, Mackay undertook to despatch these last, as they were

obnoxious to him, on account of the part they had taken against him, in

revealing the burning at Sanset. They persuaded themselves that the house

of Sutherland would defend the clan, as they were bound to do by their

promise, and that that house would be thus drawn into some snare. To

confirm their friendship, the earl and Mackay arranged that John Mackay,

the only brother of Sir Donald, should marry a niece of the earl, a

daughter of James Sinclair of Murkle, who was a mortal enemy of all the

clan Gun. Having thus planned the line of conduct they were to follow,

they parted, after swearing to continue in perpetual friendship.

Notwithstanding the private way in which the meeting

was held, accounts of it immediately spread through the kingdom; and every

person wondered at the motives which could induce Sir Donald Mackay to

take such a step so unadvisedly, without the knowledge of his uncles, Sir

Robert and Sir Alexander Gordon, or of Lord Forbes. The clan Gun receiving

secret intelligence of the design upon them, from different friendly

quarters, retired into Sutherland. The clan were astonished at Mackay’s

conduct, as he had promised, at Edinburgh, in presence of Lords Forbes and

Elphingston and Sir Robert Gordon, in the year 1616, to be a perpetual

friend to them, and chiefly to John Gun and to his cousin Alexander.

After Mackay returned from Caithness, he sent his

cousin-german, Angus Mackay of Big-house, to Sutherland, to acquaint his

uncles, who had received notice of the meeting, that his object in meeting

the Earl of Caithness was for his own personal benefit, and that nothing

had been done to their prejudice. Angus Mackay met Sir Robert Gordon at

Dunrobin, to whom he delivered his kinsman’s message, which, he said, he

hoped Sir Robert would take in good part, adding that Sir Donald would

show, in presence of both his uncles, that the clan Gun had failed in duty

and fidelity to him and the house of Sutherland, since they had revealed

the burning; and therefore, that if his uncles would not forsake John Gun,

and some others of the clan, he would adhere to them no longer. Sir Robert

Gordon returned a verbal answer by Angus Mackay, that when Sir Donald came

in person to Dunrobin to clear himself, as in duty he was bound to do, he

would then accept of his excuse, and not till then. And he at the same

time wrote a letter to Sir Donald, to the effect that for his own (Sir

Robert’s) part, he did not much regard Mackay’s secret journey to

Caithness, and his reconciliation with Earl George, without his knowledge

or the advice of Lord Forbes; and that, however unfavourable the world

might construe it, he would endeavour to colour it in the best way he

could, for Mackay’s own credit. He desired Mackay to consider that a man’s

reputation was exceedingly tender, and that if it were once blemished,

though wrongfully, there would still some blot remain, because the greater

part of the world would always incline to speak the worst; that whatever

had been arranged in that journey, between him and the Earl of Caithness,

beneficial to Mackay and not prejudicial to the house of Sutherland, he

should be always ready to assist him therein, although concluded without

his consent. As to the clan Gun, he could not with honesty or credit

abandon them, and particularly John and his cousin Alexander, until tried

and found guilty, as he had promised faithfully to be their friend, for

revealing the affair of Sanset; that he had made them this promise at the

earnest desire and entreaty of Sir Donald himself; that the house of

Sutherland did always esteem their truth and constancy to be their

greatest jewel; and seeing that he and his brother, Sir Alexander, were

almost the only branches of it then of age or man’s estate, they would

endeavour to prove true and constant wheresoever they did possess

friendship; and that neither the house of Sutherland, nor any greater

house whereof they had the honour to be descended, should have the least

occasion to be ashamed of them in that respect; that if Sir Donald had

quarrelled or challenged the clan Gun, before going into Caithness and his

arrangement with Earl George, the clan might have been suspected; but he

saw no reason to forsake them until they were found guilty of some great

offence.

Sir Robert Gordon, therefore, acting as tutor for his nephew,

took the clan Gun under his immediate protection, with the exception of

Alexander Gun, the burner of the corn, and his accomplices. John Gun

thereupon demanded a trial before his friends, that they might hear what

Sir Donald had to lay to his charge. John and his kinsmen were acquitted,

and declared innocent of any offence, either against the house of

Sutherland or Mackay, since the fact of the burning.

Sir Donald Mackay, dissatisfied with this result, went

to Edinburgh for the purpose of obtaining a commission against the clan

Gun from the council, for old crimes committed by them before his majesty

had left Scotland for England; but he was successfully opposed in this by

Sir Robert Gordon, who wrote a letter to the Lord-Chancellor and to the

Earl of Melrose, afterwards Earl of Haddington and Lord Privy Seal,

showing that the object of Sir Donald, in asking such a commission, was to

break the king’s peace, and to breed fresh troubles in Caithness.

Disappointed in this attempt, Sir Donald returned home to Strathnaver,

and, in the month of April, 1618, he went to Braill, in Caithness, where

he met the earl, with whom he continued three nights. On this occasion

they agreed to despatch Alexander Gun, the burner of the corn, lest Lord

Forbes should request the earl to deliver him up; and they hoped that, in

consequence of such an occurrence, the tribe might be ensnared. Before

parting, the earl delivered to Mackay some old writs of certain lands in

Strathnaver and other places within the diocese of Caithness, which

belonged to Sir Donald’s predecessors; by means of which the earl

thought he would put Sir Donald by the ears with his uncles, expecting him

to bring an action against the Earl of Sutherland, for the warrandice of

Strathnaver, and thus free himself from the superiority of the Earl of

Sutherland.

Shortly after this meeting was held, Sir Donald entered

Sutherland privately, for the purpose of capturing John Gun; but, after

lurking two nights in Golspie, watching Gun, without effect, he was

discovered by Adam Gordon of Kilcalmkill, a trusty dependant of the house

of Sutherland, and thereupon returned to his country. In the meantime the

Earl of Caithness, who sought every opportunity to quarrel with the house

of Sutherland, endeavoured to pick a quarrel with Six Alexander Gordon

about some sheilings which he alleged the latter’s servants had erected

beyond the marches between Torrish, in Strathully, and the lands of

Berridale. The dispute, however, came to nothing.

When Sir Robert Gordon heard of these occurrences in

the north, he returned home from Edinburgh, where he had been for some

time; and, on his return, he visited the Marquis of Huntly at Strathbogie,

who advised him to be on his guard, as he had received notice from the

Earl of Caithness that Sir Donald meant to create some disturbances in

Sutherland. The object the earl had in view, in acquainting the marquis

with Mackay’s intentions, was to screen himself from any imputation of

being concerned in Mackay’s plans, although he favoured them in secret.

As soon as Sir Robert Gordon was informed of Mackay’s intentions he

hastened to Sutherland; but before his arrival there, Sir Donald had

entered Strathully with a body of men, in quest of Alexander Gun, the

burner, against whom he had obtained letters of caption. He expected that

if he could find Gun in Strathully, where the clan of that name chiefly

dwelt, they, and particularly John Gun, would protect Alexander, and that

in consequence he would ensnare John Gun and his tribe, and bring them

within the reach of the law, for having resisted the king’s authority;

but Mackay was disappointed in his expectations, for Alexander Gun

escaped, and none of the clan Gun made the least movement, not knowing how

Sir Robert Gordon was affected towards Alexander Gun. In entering

Strathully, without acquainting his uncles of his intention, Sir Donald

had acted improperly, and contrary to his duty, as the vassal of the house

of Sutherland: but, not satisfied with this trespass, he went to Badinloch,

and there apprehended William M’Corkill, one of the clan Gun, and

carried him along with him towards Strathnaver, on the ground that he had

favoured the escape of Alexander Gun; but M’Corkill escaped while his

keepers were asleep, and went to Dunrobin, where he met Sir Alexander

Gordon, to whom he related the circumstance.

Hearing that Sir Robert Gordon was upon his journey to Sutherland,

Mackay left Badinloch in haste, and went privately to the parish of

Culmaly, taking up his residence in Golspietour with John Gordon, younger

of Embo, till he should learn in what manner Sir Robert would act towards

him. Mackay, perceiving that his presence in Golspietour was likely to

lead to a tumult among the people, sent his men home to Strathnaver, and

went himself the following day, taking only one man along with him, to

Dunrobin castle, where he met Sir Robert Gordon, who received him kindly

according to his usual manner; and after Sir Robert had opened his mind

very freely to him on the bad course he was pursuing, he began to talk to

him about a reconciliation with John Gun; but Sir Donald would not hear of

any accommodation, and after staying a few days at Dunrobin, returned home

to his own country.

Sir Donald Mackay, perceiving the danger in which he

had placed himself, and seeing that he could put no reliance on the hollow

and inconstant friendship of the Earl of Caithness, became desirous of a

reconciliation with his uncles, and with this view he offered to refer all

matters in dispute to the arbitrament of friends, and to make such

satisfaction for his offences as they might enjoin. As Sir Robert Gordon

still had a kindly feeling towards Mackay, and as the state in which the

affairs of the house of Sutherland stood during the minority of his

nephew, the earl, could not conveniently admit of following out hostile

measures against Mackay, Sir Robert embraced his offer. The parties,

therefore, met at Tain, and matters being discussed in presence of Sir

Alexander Gordon of Navidale, George Monroe of Milntoun, and John Monroe

of Leanilair, they adjudged that Sir Donald should send Angus Mackay of

Bighouse, and three gentlemen of the Slaight-ean-Aberigh, to Dunrobin,

there to remain prisoners during Sir Robert’s pleasure, as a punishment

for apprehending William M’Corkill at Badinloch. After settling some

other matters of little moment, the parties agreed to hold another meeting

for adjusting all remaining questions, at Elgin, in the month of June of

the following year, 1619. Sir Donald wished to include Gordon of Embo and

others of his friends in Sutherland in this arrangement; but as they were

vassals of the house of Sutherland, Sir Robert would not allow Mackay to

treat for them.

In the month of November, 1618, a disturbance took

place in consequence of a quarrel between George, Lord Gordon, Earl of

Enzie, and Sir Lauchlan Macintosh, chief of the clan Chattan, which arose

out of the following circumstances —When the earl went into Lochaber, in

the year 1613, in pursuit of the clan Cameron, he requested Macintosh to

accompany him, both on account of his being the vassal of the Marquis of

Huntly, the earl’s father, and also on account of the ancient enmity

which had always existed between the clan Chattan and clan Cameron, in

consequence of the latter keeping forcible possession of certain lands

belonging to the former in Lochaber. To induce Macintosh to join him, the

earl promised to dispossess the clan Cameron of the lands belonging to

Macintosh, and to restore him to the possession of them; but, by advice of

the laird of Grant, his father-in-law, who was an enemy of the house of

Huntly, he declined to accompany the earl in his expedition. The earl was

greatly displeased at Macintosh’s refusal, which afterwards led to some

disputes between them. A few years after the date of this expedition—in

which the earl subdued the clan Cameron, and took their chief prisoner,

whom he imprisoned at Inverness in the year 1614—Macintosh obtained a

commission against Macronald, younger of Keppoch, and his brother, Donald

Glass, for laying waste his lands in Lochaber; and, having collected all

his friends, he entered Lochaber for the purpose of apprehending them,

but, being unsuccessful in his attempt, he returned home. As Macintosh

conceived that he had a right to the services of all his clan, some of

whom were tenants and dependants of the Marquis of Huntly, he ordered

these to follow him, and compelled such of them as were refractory to

accompany him into Lochaber. This proceeding gave offence to the Earl of

Enzie, who summoned Macintosh before the lords of the Privy Council for

having, as he asserted, exceeded his commission. He, moreover, got

Macintosh’s commission recalled, and obtained a new commission in his

own favour from the Lords of the council, under which he invaded Lochaber

and expelled Macronald and his brother Donald from that country.

As Macintosh held certain lands from the earl and his

father for services to be done, which the earl alleged had not been

performed by Macintosh agreeably to the tenor of his titles, the earl

brought an action against Macintosh in the year 1618 for evicting these

lands, on the ground of his not having implemented the conditions on which

he held them. And, as the earl had a right to the tithes of Culloden,

which belonged to Macintosh, he served him, at the same time, with an

inhibition, prohibiting him to dispose of these tithes. As the time for

tithing drew near, Macintosh, by advice of the clan Kenzie and the Grants,

circulated a report that he intended to oppose the earl in any attempt he

might make to take possession of the tithes of Culloden in kind, because

such a practice had never before been in use, and that he would try the

issue of an action of spuilzie, if brought against him. Although the earl

was much incensed at such a threat on the part of his own vassal, yet,

being a privy counsellor, and desirous of showing a good example in

keeping the peace, he abstained from enforcing his right; but, having

formerly obtained a decree against Macintosh for the value of the tithes

of the preceding years, he sent two messengers-at-arms to poind and

distrain the crops upon the ground under that warrant. The messengers

were, however, resisted by Macintosh’s servants, and forced to desist

from the execution of their duty. The earl, in consequence, pursued

Macintosh and his servants before the Privy Council, and got them

denounced and proclaimed rebels to the king. He, thereupon, collected a

number of his particular friends with the design of carrying his decree

into execution, by distraining the crop at Culloden and carrying it to

Inverness. Macintosh prepared himself to resist, by fortifying the house

of Culloden and laying in a large quantity of ammunition; and having

collected all the corn within shot of the castle and committed the charge

of it to his two uncles, Duncan and Lanchlan, he waited for the approach

of the earl. As the earl was fully aware of Macintosh’s preparations,

and that the clan Chattan, the Grants, and the clan Kenzie, had promised

to assist Macintosh in opposing the execution of his warrant, he wrote to

Sir Robert Gordon, tutor of Sutherland, to meet him at Culloden on the 5th

of November, 1618, being the day fixed by him for enforcing his decree. On

receipt of this letter, Sir Robert Gordon left Sutherland for Bog-a-Gight,

where the Marquis of Huntly and his son then were, and on his way paid a

visit to Macintosh with the view of bringing about a compromise; but

Macintosh, who was a young man of a headstrong disposition, refused to

listen to any proposals, and rode post-haste to Edinburgh, from which he

went privately into England.

In the meantime, the Earl of Enzie having collected his

friends, to the number of 1,100 horsemen well appointed and armed, and 600

Highlanders on foot, came to Inverness with this force on the day

appointed, and, after consulting his principal officers, marched forwards

towards Culloden. When he arrived within view of the castle, the earl sent

Sir Robert Gordon to Duncan Macintosh, who, with his brother, commanded

the house, to inform him that, in consequence of his nephew’s

extraordinary boasting, he had come thither to put his majesty’s laws in

execution, and to carry off the corn which of right belonged to him. To

this message Duncan replied, that he did not mean to prevent the earl from

taking away what belonged to him, but that, in case of attack, he would

defend the castle which had been committed to his charge. Sir Robert, on

his return, begged the earl to send Lord Lovat, who had seine influence

with Duncan Macintosh, to endeavour to prevail on him to surrender the

castle. At the desire of the earl, Lord Lovat accordingly went to the

house of Culloden, accompanied by Sir Robert Gordon and George Monroe of

Milntoun, and, after some entreaty, Macintosh agreed to surrender at

discretion; a party thereupon took possession of the house, and sent the

keys to the earl. He was, however, so well pleased with the conduct of

Macintosh, that he sent back the keys to him, and as neither the clan

Chattan, the Grants, nor the clan Kenzie, appeared to oppose him, he

disbanded his party and returned home to Bog-a-Gight. He did not even

carry off the corn, but gave it to Macintosh’s grandmother, who enjoyed

the life-rent of the lands of Culloden as her jointure.

As the Earl of Enzie had other claims against Sir

Lauchlan Macintosh, he cited him before the lords of council and session,

but failing to appear, he was again denounced rebel, and outlawed for his

disobedience. Sir Lauchlan, who was then in England at court, informed the

king of the earl’s proceedings, which he described as harsh and illegal,

and, to counteract the effect which such a statement might have upon the

mind of his majesty, the earl posted to London and laid before him a true

statement of matters. The consequence was, that Sir Lauchlan was sent home

to Scotland and committed to the castle of Edinburgh, until he should give

the earl full satisfaction. This step appears to have brought him to

reason, and induced him to apply, through the mediation of some friends,

for a reconciliation with the earl, which took place accordingly, at

Edinburgh, in the year 1619. Sir Lauchlan, however, became bound to pay a

large sum of money to the earl, part of which the latter afterwards

remitted. The laird of Grant, by whose advice Macintosh had acted in

opposing the earl, also submitted to the latter; but the reconciliation

was more nominal than real, for the earl was afterwards obliged to protect

the chief of the clan Cameron against them, and this circumstance gave

rise to many dissensions between them and the earl, which ended only with

the lives of Macintosh and the laird of Grant, who both died in the year

1622, when the ward of part of Macintosh’s lands fell to the earl, as

his superior, during the minority of his son. The Earl of Seaforth and his

clan, who had also favoured the designs of Macintosh, were in like manner

reconciled, at the same time, to the Earl of Enzie, at Aberdeen, through

the mediation of the Earl of Dunfermline, the Chancellor of Scotland,

whose daughter the Earl of Seaforth had married.

In no part of the Highlands did the spirit of faction

operate so powerfully, or reign with greater virulence, than in Sutherland

and Caithness and the adjacent country. The jealousies and strifes which

existed for such a length of time between the two great rival families of

Sutherland and Caithness, and the warfare which these occasioned, sowed

the seeds of a deep-rooted hostility, which extended its baneful influence

among all their followers, dependants, and friends, and retarded their

advancement. The most trivial offences were often magnified into the

greatest crimes, and bodies of men, animated by the deadliest hatred, were

instantly congregated to avenge imaginary wrongs. It would be almost an

endless task to relate the many disputes and differences which occurred

during the seventeenth century in these distracted districts; but as a

short account of the principal events is necessary in a work of this

nature, we again proceed agreeably to our plan.

The resignation which the Earl of Caithness was

compelled to make of part of the feu lands of the bishopric of Caithness,

into the hands of the bishop, as before related, was a measure which

preyed upon his mind, naturally restless and vindictive, and in

consequence he continually annoyed the bishop’s servants and tenants.

His hatred was more especially directed against Robert Monroe of Aldie,

commissary of Caithness, who always acted as chamberlain to the bishop,

and factor in the diocese, whom he took every opportunity to molest. The

earl had a domestic servant, James Sinclair of Dyren, who had possessed

part of the lands which he had been compelled to resign, and which were

now tenanted by Thomas Lindsay, brother-uterine of Robert Monroe, the

commissary. This James Sinclair, at the instigation of the earl,

quarrelled with Thomas Lindsay, who was passing at the time near the earl’s

house in Thurso, and, after changing some hard words, Sinclair inflicted a

deadly wound upon him, of which he shortly thereafter died. Sinclair

immediately fled to Edinburgh, and thence to London, to meet Sir Andrew

Sinclair, who was transacting some business for the king of Denmark there,

that he might intercede with the king for a pardon; but his majesty

refused to grant it, and Sinclair, for better security, went to Denmark

along with Sir Andrew.

As Robert Monroe did not consider his person safe in Caithness under

such circumstances, he retired into Sutherland for a time. He then pursued

James Sinclair and his master, the Earl of Caithness, for the slaughter of

his brother, Thomas Lindsay; but, not appearing for trial on the day

appointed, they were both outlawed, and denounced rebels. Hearing that

Sinclair was in London, Monroe hastened thither, and in his own name and

that of the bishop of Caithness, laid a complaint before his majesty

against the earl and his servant. His majesty thereupon wrote to the Lords

of the Privy Council of Scotland, desiring them to adopt the most speedy

and rigorous measures to suppress the oppressions of the earl, that his

subjects in the north who were well affected might live in safety and

peace; and to enable them the more effectually to punish the earl, his

majesty ordered them to keep back the remission that had been granted for

the affair at Sanset, which had not yet been delivered to him. His majesty

also directed the Privy Council, with all secrecy and speed, to give a

commission to Sir Robert Gordon to apprehend the earl, or force him to

leave the kingdom, and to take possession of all his castles for his

majesty’s behoof; that he should also compel the landed proprietors of

Caithness to find surety, not only for keeping the king’s peace in time

coming, but also for their personal appearance at Edinburgh twice every

year, as the West Islanders were bound to do, to answer to such complaints

as might be made against them. The letter containing these instructions is

dated from Windsor, 25th May, 1621.

The Privy Council, on

receipt of this letter, communicated the same to Sir Robert Cordon who was

then in Edinburgh; but he excused himself from accepting the commission

offered him, lest his acceptance might be construed as proceeding from

spleen and malice against the Earl of Caithness. This answer, however, did

not satisfy the Privy Council, which insisted that he should accept the

commission; he eventually did so, but on condition that the council should

furnish him with shipping and the munitions of war, and all other

necessaries to force the earl to yield, in case he should fortify either

Castle Sinclair or Ackergill, and withstand a siege.

While

the Privy Council were deliberating on this matter, Sir Robert Gordon took

occasion to speak to Lord

Berridale, who was still a prisoner for debt in the jail of Edinburgh,

respecting the contemplated measures against the earl, his father. As Sir

Robert was still very unwilling to enter upon such an enterprise, he

advised his lordship to undertake the business, by engaging in which he

might not only get himself relieved of the claims against him, save his

country from the dangers which threatened it, but also keep possession of

his castles; and that as his father had treated him in the most unnatural

manner, by suffering him to remain so long in prison without taking any

steps to obtain his liberation, he would be justified, in the eyes of the

world, in accepting the offer now made. Being encouraged by Lord Gordon,

Earl of Enzie, to whom Sir Robert Gordon’s proposal had been

communicated, to embrace the offer, lord Berridale offered to undertake

the service without any charge to his majesty, and that he would, before

being liberated, give security to his creditors, either to return to

prison after he had executed the commission, or satisfy them for their

claims against him. The Privy Council embraced at once Lord Berridale’s

proposal, but, although the Earl of Enzie offered himself as surety for

his lordship’s return to prison after the service was over, the

creditors refused to consent to his liberation, and thus the matter

dropped. Sir Robert Gordon was again urged by the council to accept the

commission, and to make the matter more palatable to him, they granted the

commission to him and the Earl of Enzie jointly, both of whom accepted it.

As the council, however, had no command from the king to supply the

commissioners with shipping and warlike stores, they delayed proceedings

till they should receive instructions from his majesty touching that

point.

When the Earl of Caithness

was informed of the proceedings contemplated against him, and that Sir

Robert Gordon had been employed by a commission from his majesty to act in

the matter, he wrote to the Lords of the Privy Council, asserting that he

was innocent of the death of Thomas Lindsay; that his reason for not

appearing at Edinburgh to abide his trial for that crime, was not that he

had been in any shape privy to the slaughter, but for fear of his

creditors, ‘who, he was afraid, would apprehend and imprison him; and

promising, that if his majesty would grant him a protection and

safe-conduct, he would find security to abide trial for the slaughter of

Thomas Lindsay. On receipt of this letter, the lords of the council

promised him a protection, and in the month of August, his brother, James

Sinclair of Murkle, and Sir John Sinclair of Greenland, became sureties

for his appearance at Edinburgh, at the time prescribed for his appearance

to stand trial. Thus the execution of the commission was in the meantime

delayed.

Notwithstanding the refusal

of Lord Berridale’s creditors to consent to his liberation, Lord Gordon

afterwards did all in his power to accomplish it, and ultimately succeeded

in obtaining this consent, by giving his own personal security either to

satisfy the creditors, or deliver up Lord Berridale into their hands. His

lordship was accordingly released from prison, and returned to Caithness

in the year 1621, after a confinement of five years. As his final

enlargement from jail depended upon his obtaining the means of paying his

creditors, and as his father, the earl, staid at home consuming the rents

of his estates, in rioting and licentiousness, without paying any part