|

In the year 1610 the Earl

of Caithness and Houcheon Mackay, chief of the Mackays, had a difference

in consequence of the protection given by the latter to a gentleman named

John Sutherland, the son of Mackay’s sister. Sutherland lived in

Berridale, under the Earl of Caithness, but he was so molested by the earl

that he lost all patience, and went about avenging the injuries he had

sustained. The earl, therefore, cited him to appear at Edinburgh to answer

to certain charges made against him; but not obeying the summons, he was

denounced and proclaimed a rebel to the king. Reduced, in consequence, to

great extremities, and seeing no remedy by which he could retrieve

himself, he became an outlaw, wasted and destroyed the earl’s country,

and carried off herds of cattle, which he transported into Strathnaver,

the country of his kinsman. The earl thereupon sent a party of the

Siol-MhicImheair to attack him, and, after a long search, they found him

encamped near the water of Shin in Sutherland. He, however, was aware of

their approach before they perceived him, and, taking advantage of this

circumstance, attacked them in the act of crossing the water. They were in

consequence defeated, leaving several of their party dead on the field.

This disaster exasperated

the earl, who resolved to prosecute Mackay and his son, Donald Mackay, for

giving succour and protection within their country to John Sutherland, an

outlaw. Accordingly, he served both of them with a notice to appear before

the Privy Council to answer to the charges he had preferred against them.

Mackay at once obeyed the summons, and went to Edinburgh, where he met Sir

Robert Gordon, who had come from England for the express purpose of

assisting Mackay on the present occasion. The earl, who had grown tired of

the troubles which John Sutherland had occasioned in his country, was

induced, by the entreaties of friends, to settle matters on the following

conditions:- That he should forgive John Sutherland all past injuries, and

restore him to his former possessions; that John Sutherland and his

brother Donald should be delivered, the one after the other, into the

hands of the earl, to be kept prisoners for a certain time; and that

Donald Mac-Thomais-Mhoir, one of the Sliochd-Iain-Abaraich, and a follower

of John Sutherland in his depredations, should be also delivered up to the

earl to be dealt with as to him should seem meet; all of which

stipulations were complied with. The earl hanged Donald Mac-Thomais as

soon as he was delivered up. John Sutherland was kept a prisoner at

Girnigo about twelve months, during which time Donald Mackay made several

visits to Earl George for the purpose of getting him released, in which he

at last succeeded, besides procuring a discharge to Donald Sutherland,

who, in his turn, should have surrendered himself as prisoner on the

release of his brother John, but upon the condition that he and his

father, Houcheon Mackay, should pass the next following Christmas with the

earl at Girnigo. Mackay and his brother William, accordingly, spent their

Christmas at Girnigo, but Donald Mackay was prevented by business from

attending. The design of the Earl of Caithness in thus favouring Mackay,

was to separate him from the interests of the Earl of Sutherland, but he

was unsuccessful.

Some years before the

events we have just related, a commotion took place in Lewis, occasioned

by the pretensions of Torquill Connaldagh of the Cogigh to the possessions

of Roderick Macleod of Lewis, his reputed father. Roderick had first

married Barbara Stuart, daughter of Lord Methven, by whom he had a son

named Torquill-Ire, who, on arriving at manhood, gave proofs of a warlike

disposition. Upon the death of Barbara Stuart, Macleod married a daughter

of Mackenzie, lord of Kintail, whom he afterwards divorced for adultery

with the Breve of Lewis, a sort of judge among the islanders, to whose

authority they submitted themselves. Macleod next married a daughter of

Maclean, by whom he had two sons, Torquihl Dubli and Tormaid.

In sailing from Lewis to

Skye, Torquil-Ire, eldest son of Macleod, and 200 men perished in a great

tempest. Torquill Connaldagh, above mentioned, was the fruit of the

adulterous connexion between Macleod’s second wife and the Breve, at

least Macheed would never acknowledge him as his son. This Torquill being

now of age, and having married a sister of Glengarry, took up arms against

Macleod, his reputed father, to vindicate his supposed rights as Macleod’s

son, being assisted by Tormaid, Ougigh, and Murthow, three of the bastard

sons of Maleod. The old man was apprehended and detained four years in

captivity, when he was released on condition that he should acknowledge

Torquill Connaldagh as his lawful son. Tormaid Ougigh having been slain by

Donald Macleod, his brother, another natural son of old Macleod, Torquihl

Connaidagh, assisted by Murthow Maleod, his reputed bastard brother, took

Donald prisoner and earned him to Cogigh, but he escaped and fled to his

father in Lewis, who was highly offended at Torquil for seizing his son

Donald. Macleod then caused Donald to apprehend Murthow, and having

delivered him to his father, he was imprisoned in the castle of Stornoway.

As soon as Torqnihl heard of this occurrence, he went to Stornoway and

attacked the fort, which he took, after a short siege, and released

Murthow. He then apprehended Rodenick Macleod, killed a number of his men,

and carried off all the charters and other title-deeds of Lewis, which he

gave in custody to the Mackenzies. Torquill had a son named John Macleod,

who was in the service of the Marquis of Huntly; he now sent for him, and

on his arrival committed to him the charge of the castle of Stornoway in

which old Macleod was imprisoned. John Macleod being now master of Lewis,

and acknowledged superior thereof, proceeded to expel Rorie-Og and Donald,

two of Roderick Macleod’s bastard sons, from the island; but Ronie-Og

attacked him in Stornoway, and after killing him, released Roderick

Macleod, his father, who possessed the island in peace during the

remainder of his life. Torquill Connahdagh, by the assistance of the clan

Kenzie, got Donald Macleod into his possession, and executed him at

Dingwall.

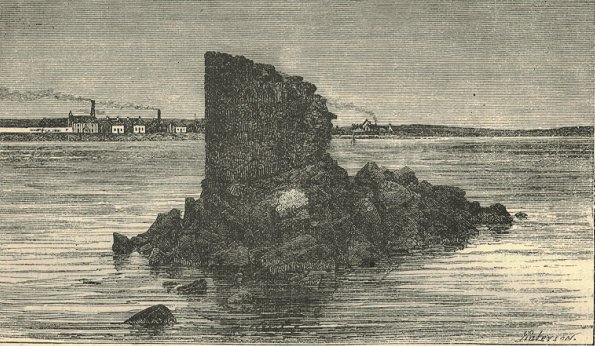

Stornaway Castle

Upon the death of Rodenick Macleod, his son

Torquill Dubh succeeded him in Lewis Taking a grudge at Rorie-Og, his

brother, he apprehended him, and sent him to Maclean to be detained in

prison; but he escaped out of Maclean’s hands, and afterwards perished

in a snow-storm. As Torquill Dubh excluded Torquill Connaldagh from the

succession of Lewis, as a bastard, the clan Kenzie formed a design to

purchase and conquer Lewis, which they calculated on accomplishing on

account of the simplicity of Torquili Connaldagh, who had now no friend to

advise with, and from the dissensions which unfortunately existed among

the race of the Siol-Torquill. This scheme, moreover, received the aid of

a matrimonial alliance between Torquill Connaldagh and the clan, by a

marriage between his eldest daughter and Roderick Mackenzie, the lord of

Kintail’s brother. The clan did not avow their design openly, but they

advanced their enterprise under the pretence of assisting Torqulll

Connaldagh, who was a descendant of the Kintail family, and they

ultimately succeeded in destroying the family of Macleod of Lewis,

together with his tribe, the Siol-Torquill, and by the ruin of that family

and some neighbouring clans, this ambitious clan made themselves complete

masters of Lewis and other places. As Torquill Dubh was the chief obstacle

in their way, they formed a conspiracy against his life, which, by the

assistance of the Breve, they were enabled to carry out successfully. The

Breve, by stratagem, managed to obtain possession of Torquil] Dubh and

some of his friends, and deliver them to the lord of Kintail, who ordered

them to be beheaded, which they accordingly were in July, 1597.

Some gentlemen belonging to

Fife, hearing of these disturbances in Lewis, obtained from the king, in

1598, a gift of the island, their professed object being to civilize the

inhabitants, their real design, however, being, by means of a colony, to

supplant the inhabitants, and drive them from the island. A body of

soldiers and artificers of all sorts were sent, with every thing necessary

for a plantation, into Lewis, where, on their arrival, they began to erect

houses in a convenient situation, and soon completed a small but neat

town, in which they took up their quarters. The new settlers were,

however, much annoyed in their operations by Neill and Murthow Macleod,

the only sons of Roderick Macleod who remained in the island. The

speculation proved ruinous to many of the adventurers, who, in consequence

of the disasters they met with, lost their estates, and were in the end

obliged to quit the island.

In the meantime, Neill Macleod quarrelled

with his brother Murthow, for harbouring and maintaining the Breve and

such of his tribe as were still alive, who had been the chief instruments

in the murder of Torquill Dubh. Neil thereupon apprehended his brother,

and some of the clan Mhic-Ghille-Mhoir, all of whom he killed, reserving

his brother only alive. When the Fife speculators were informed that Neill

had taken Murthow, his brother, prisoner, they sent him a message offering

to give him a share of the island, and to assist him in revenging the

death of Torquill Dubh, provided he would deliver Murthow into their

hands. Neill agreed to this proposal, and having gone thereafter to

Edinburgh, he received a pardon from the king for all his past offences.

These proceedings

frustrated for a time the designs of the Mackenzies upon the island, and

the lord of Kintail almost despaired of obtaining possession by any means.

As the new settlers now stood in his way, he resolved to desist from

persecuting the Siol-Torquill, and to cross the former in their

undertakings, by all the means in his power. He had for some time kept

Tormaid Macleod, the lawful brother of Torquill Dubh, a prisoner; but he

now released him, thinking that upon his appearance in the Lewis all the

islanders would rise in his favour; and he was not deceived in his

expectations, for, as Sir Robert Gordon observes, "all these

islanders, (and lykwayes the Hielanders,) are, by nature, most bent and

prone to adventure themselves, their lyffs, and all they have, for their

masters and lords, yea beyond all other people." In the meantime

Murthow Macleod was carried to St. Andrews, and there executed. Having at

his execution revealed the designs of the lord of Kintail, the latter was

committed, by order of the king, to the castle of Edinburgh, from which,

however, he contrived to escape without trial, by means, as is supposed,

of the then Lord-Chancellor of Scotland.

On receiving pardon Neill

Macleod returned into Lewis with the Fife adventurers; but he had not been

long in the island when he quarrelled with them on account of an injury he

had received from Sir James Spence of Wormistoun. He therefore abandoned

them, and watched a favourable opportunity for attacking them. They then

attempted to apprehend him by a stratagem, but only succeeded in bringing

disaster upon themselves. Upon hearing of this the lord of Kintail thought

the time was now suitable for him to stir, and accordingly he sent Tormaid

Macleod into Lewis, as he had intended, promising him all the assistance

in his power if he would attack the Fife settlers.

As soon as Tormaid arrived

in the island, his brother Neill and all the natives assembled and

acknowledged him as their lord and master. He immediately attacked the

camp of the adventurers, which he forced, burnt the fort, killed the

greater part of their men, took the commanders prisoners, whom he

released, after a captivity of eight months, on their solemn promise not

to return again to the island, and on their giving a pledge that they

should obtain a pardon from the king for Tormaid and his followers for all

past offences. After Tormaid had thus obtained possession of the island,

John Mac-Donald-Mac-Houcheon apprehended Torquill Connaldagh, and carried

him into Lewis to his brother, Tormaid Macleod. Tormaid inflicted no

punishment upon Connaldagh, but merely required from him delivery of the

title-deeds of Lewis, and the other papers which he had carried off when

he apprehended his father Roderick Macleod. Connaldagh informed him that

he had it not in his power to give them up, as he had delivered them to

the clan Kenzie, in whose possession they still were. Knowing this to be

the fact, Tormaid released Torquill Connaldagh, and allowed him to leave

the island, contrary to the advice of all his followers and friends, who

were for inflicting the punishment of death upon Torquill, as he had been

the occasion of all the miseries and troubles which had befallen them.

The Breve of Lewis soon met with a just

punishment for the crime he had committed in betraying and murdering his

master, Torquill Dubh Macleod. The Breve and some of his relations had

taken refuge in the country of Assynt. John Mac-Donald-Mac-Houcheon,

accompanied by four persons, having accidentally entered the house where

the Breve and six of his kindred lodged, found themselves unexpectedly in

the same room with them. Being of opposite factions, a fight immediately

ensued, in the course of which the Breve and his party fled out of the

house, but were pursued by John and his men, and the Breve and five of his

friends killed.

Although the Fife settlers

had engaged not to return again into Lewis, they nevertheless made

preparations for invading it, having obtained the king’s commission

against Tormaid Macleod and his tribe, the Siol-Torquill. They were aided

in this expedition by forces from all the neighbouring counties, and

particularly by the Earl of Sutherland, who sent a party of men under the

command of William Mac-Mhic-Sheumais, chief of the clan Gun in Sutherland,

to assist in subduing Tormaid Macleod. As soon as they had effected a

landing in the island with all their forces, they sent a message to

Macleod, acquainting him that if he would surrender himself to them, in

name of the king, they would transport him safely to London, where his

majesty then was; and that, upon his arrival there, they would not only

obtain his pardon, but also allow him to deal with the king in behalf of

his friends, and for the means of supporting himself. Macleod, afraid to

risk his fortune against the numerous forces brought against him, agreed

to the terms proposed, contrary to the advice of his brother Neill, who

refused to yield. Tormaid was thereupon sent to London, where he took care

to give the king full information concerning all the circumstances of his

case; he showed his majesty that Lewis was his just inheritance, and that

his majesty had been deceived by the Fife adventurers in making him

believe that the island was at his disposal, which act of deception had

occasioned much trouble and a great loss of blood. He concluded by

imploring his majesty to do him justice by restoring him to his rights.

Understanding that Macleod’s representations were favourably received by

his majesty, the adventurers used all their influence at court to thwart

him; and as some of them were the king’s own domestic servants, they at

last succeeded so far as to get him to be sent home to Scotland a prisoner

in 1605. He remained a captive at Edinburgh till the month of March, 1615,

when the king granted him permission to pass into Holland, to Maurice,

Prince of Orange, where he ended his days. The settlers soon grew wearied

of their new possession, and as all of them had declined in their

circumstances in this luckless speculation, and as they were continually

annoyed by Neill Macleod, they finally abandoned the island, and returned

to Fife to bewail their loss.

Lord Kintail, now no longer

disguising his intentions, obtained, through means of the Lord Chancellor,

a gift of Lewis, under the great seal, for his own use, in virtue of the

old right which Torquill Connaldagh had long before resigned in his favour.

Some of the adventurers having complained to the king of this proceeding,

his majesty became highly displeased at Kintail, and made him resign his

right into his majesty’s hands by means of Lord Balmerino, then

Secretary of Scotland, and Lord President of the session; which right his

majesty now (1608) vested in the persons of Lord Balmerino, Sir George

Hay, afterwards Chancellor of Scotland, and Sir James Spence of Wormistoun.

Balmerino, on being convicted of high treason in 1609, lost his share, but

Hay and Spence undertook the colonization of Lewis, and accordingly made

great preparations for accomplishing their purpose. Being assisted by most

of the neighbouring countries, they invaded Lewis for the double object of

planting a colony, and of subduing and apprehending Neil Macleod, who now

alone defended the island.

On this occasion Lord Kintail played a

double part, for while he sent Roderick Mackenzie, his brother, with a

party of men openly to assist the new colonists who acted under the king’s

commission,—promising them at the same time his friendship, and sending

them a vessel from Ross with a supply of provisions,— he privately sent

notice to Neili Macleod to intercept the vessel on her way; so that the

settlers, being disappointed in the provisions to which they trusted,

might abandon the island for want. The case turned out exactly as Lord

Kintail anticipated, as Sir George Hay and Sir James Spence abandoned the

island, leaving a party of men behind to keep the fort, and disbanded

their forces, returning into Fife, intending to have sent a fresh supply

of men, with provisions, into the island. But Neil Macleod having, with

the assistance of his nephew, Malcolm Macleod, son of Rederick Og, burnt

the fort, and apprehended the men who were left behind in the island, whom

he sent safely home, the Fife gentlemen abandoned every idea of again

taking possession of the island, and sold their right to Lord Kintail. He

likewise obtained from the king a grant of the share of the island

forfeited by Balmerino, and thus at length acquired what he had so long

and anxiously desired.

Lord Kintail lost no time

in taking possession of the island,—and all the inhabitants, shortly

after his landing, with the exception of Neill Macleod and a few others,

submitted to him. Neill, along with his nephews, Malcolm, William, and

Roderick, the three sons of Roderick Og, the four sons of Torquill Blair,

and thirty others, retired to an impregnable rock in the sea called

Berrissay, on the west of Lewis, into which Neill had been accustomed, for

some years, to send provisions and other necessary articles to serve him

in case of necessity. Neill lived on this rock for three years, Lord

Kintall in the meantime dying in 1611. As Macleod could not be attacked in

his impregnable position, and as his proximity was a source of annoyance,

the clan Kenzie fell on the following expedient to get quit of him. They

gathered together the wives and children of those that were in Berrissay,

and also all persons in the island related to them by consanguinity or

affinity, and having placed them on a rock in the sea, so near Berrissay

that they could be heard and seen by Neil and his party, the clan Kenzie

vowed that they would suffer the sea to overwhelm them, on the return of

the flood-tide, if Neil did not instantly surrender the fort. This

appalling spectacle had such an effect upon Macleod and his companions,

that they immediately yielded up the rock and left Lewis.

Neill Macleod then retired

into Harris, where he remained concealed for a time; but not being able to

avoid discovery any longer, he gave himself up to Sir Rodcrick Macleod of

Harris, and entreated him to carry him into England to the king, a request

with which Sir Roderick promised to comply. In proceeding on his journey,

however, along with Macleod, he was charged at Glasgow, under pain of

treason, to deliver up Neil to the privy council. Sir Roderick obeyed the

charge, and Neill, with his eldest son Donald, were presented to the privy

council at Edinburgh, white Neill was executed in April 1613. His son

Donald was banished from the kingdom of Scotland, and immediately went to

England, where he remained three years with Sir Robert Gordon, tutor of

Sutherland, and from England he afterwards went to Holland, where he died.

After the death of Neill

Macleod, Roderick and William, the sons of Roderick Og, were apprehended

by Roderick Mackenzie, tutor of Kintail, and executed. Malcolm Macleod,

his third son, who was kept a prisoner by Roderick Mackenzie, escaped, and

having associated himself with the clan Donald in Islay and Kintyre during

their quarrel with the Campbells in 1615—16, he annoyed the clan Kenzie

with frequent incursions. Malcolm, thereafter, went to Flanders and Spain,

where he remained with Sir James Macdonald. Before going to Spain, he

returned from Flanders into Lewis in 1616, where he killed two gentlemen

of the clan Kenzie. He returned from Spain in 1620, and the last that is

heard of him is in 1626, when commissions of fire and sword were granted

to Lord Kintail against "Malcolm Macquari Macleod."

From the occurrences in Lewis, we now

direct the attention of our readers to some proceedings in the isle of

Rasay, which ended in bloodshed. The quarrel lay between Gille-Chalum,

baird of the island, and Murdo Mackenzie of Gairloch, and the occasion was

as follows. The lands of Gairloch originally belonged to the clan

Mhic-Ghille-Chalum, the predecessors of the baird of Rasay; and when the

Mackenzies began to prosper and to rise, one of them obtained the third

part of these lands in mortgage or wadset from the clan Mhic-Ghille-Chalum.

In process of time the clan Kenzie, by some means or other, unknown to the

proprietor of Gairloch, obtained a right to the whole of these lands, but

they did not claim possession of the whole till the death of Torqnill Dubh

Maciced of Lewis, whom the baird of Rasay and his tribe followed as their

superior. But upon the death of Torquil Dubh, the baird of Gairloch took

possession of the whole of the lands of Gairloch in virtue of his

pretended right, and chased the clan Mhic-Ghille-Chalum from the lands

with fire and sword. The clan retaliated in their turn by invading the

laird of Gairloch, plundering his lands and committing slaughters. In a

skirmish which took place in the year 1610, in which lives were lost on

both sides, the laird of Gairloch apprehended John Mac-Main-MacRory, one

of the principal men of the clan; but being desirous to get hold also of

John Holmoch-Mac-Rory, another of the chiefs, he sent his son Murdo the

following year along with Alexander Bane, the son and heir of Bane of

Tulloch in Ross, and some others, to search for and pursue John Holmoch;

and as he understood that John Holmoch was in Skye, he hired a ship to

carry his son and party thither; but instead of going to Skye, they

unfortunately, from some unknown cause, landed in Rasay.

On their arrival in Rasay

in August 1611, Gille-Chalum, laird of Rasay, with some of his followers,

went on board, and unexpectedly found Murdo Mackenzie in the vessel. After

consulting with his men, he resolved to take Mackenzie prisoner, in

security for his cousin, John Mac-Alain-Mac-Rory, whom the laird of

Gairloch detained in captivity. The party then attempted to seize

Mackenzie, but he and his party resisting, a keen conflict took place on

board, which continued a considerable time. At last, Murdo Mackenzie,

Alexander Bane, and the whole of their party, with the exception of three,

were slain. These three fought manfully, killing the laird of Rasay and

the whole men who accompanied him on board, and wounding several persons

that remained in the two boats. Finding themselves seriously wounded, they

took advantage of a favourable wind, and sailed away from the island, but

expired on the voyage homewards. From this time the Mackenzies appear to

have uninterruptedly held possession of Gairloch.

About the time this

occurrence took place, the peace of the north was almost again disturbed

in consequence of the conduct of William Mac-Angus-Roy, one of the clan

Gun, who, though born in Strathnaver, had become a servant to the Earl of

Caithness. This man had done many injuries to the people of Caithness by

command of the earl; and the mere displeasure of Earl George at any of his

people, was considered by William Mac-Angus as sufficient authority for

him to steal and take away their goods and cattle. William got so

accustomed to this kind of service, that he began also to steal the cattle

and horses of the earl, his master, and, after collecting a large booty in

this way, he took his leave. The earl was extremely enraged at his quondam

servant for so acting; but, as William MacAngus was in possession of a

warrant in writin, under the earl’s own hand, authorizing him to act as

he had done towards the people of Caithness, the earl was afraid to adopt

any proceedings against him, or against those who protected and harboured

him, before the Privy Council, lest he might produce the warrant which he

held from the earl. The confidence which the earl had reposed in him

served, however, still more to excite the earl’s indignation.

As William Mac-Angus continued his

depredations in other quarters, he was apprehended in the town of Tain, on

a charge of cattle-stealing; but he was released by the Monroes, who gave

security to the magistrates of the town for his appearance when required,

upon due notice being given that he was wanted for trial. On attempting to

escape he was redelivered to the provost and bailies of Tain, by whom he

was given up to the Earl of Caithness, who put him in fetters, and

imprisoned him within Castle Sinclair (1612). He soon again contrived to

escape, and fled into Strathnavor, the Earl of Caithness sending his son,

William, Lord Borridale, in pursuit of him. Missing the fugitive, he, in

revenge, apprehended a servant of Mackay, called Angus Henriach, without

any authority from his majesty, and carried him to Castle Sinclair, where

he was put into fetters and closely imprisoned on the pretence that he had

assisted William Mac-Angus in effecting his escape. When this occurrence

took place, Donald Mackay, son of Houcheon Mackay, the chief, was at

Dunrobin castle, and he, on hearing of the apprehension and imprisonment

of his father’s servant, could scarcely be made to believe the fact on

account of the friendship which had been contracted between his father and

the earl the preceding Christmas. But being made sensible thereof, and of

the cruel usage which the servant had received, he prevailed on his father

to summon the earl and his son to answer to the charge of having

apprehended and imprisoned Angus Henriach, a free subject of the king,

without a commission. The earl was also charged to present his prisoner

before the privy council at Edinburgh in the month of June next following,

which he accordingly did; and Angus being tried before the lords and

declared innocent, was delivered over to Sir Robert Gordon, who then acted

for Mackay.

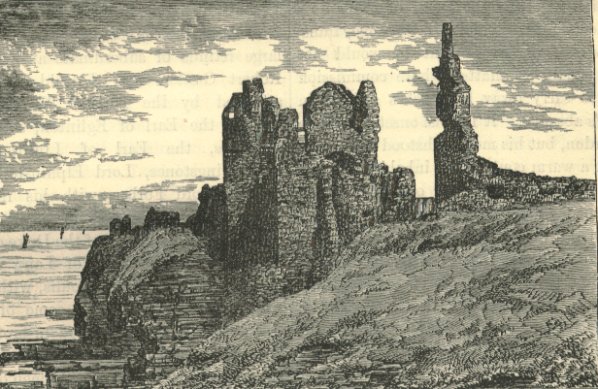

Castle Sinclair and Girnigo

During the same year (1612) another event

occurred in the north, which created considerable uproar and discord in

the northern Highlands. A person of the name of Arthur Smith, who resided

in Banff, had counterfeited the coin of the realm, in consequence of which

he, and a man who had assisted him, fled from Banff into Sutherland, where

being apprehended in the year 1599, they were sent by the Countess of

Sutherland to the king, who ordered them to be imprisoned in Edinburgh for

trial They were both accordingly tried and condemned, and having confessed

to crimes even of a deeper dye, Smith’s accomplice was burnt at the

place of execution. Smith himself was reserved for farther trial. By

devising, a lock of rare and curious workmanship, which took the fancy of

the king, he ultimately obtained his release and entered into the service

of the Earl of Caithness. His workshop was under the rock of Castle

Sinclair, in a quiet retired place called the Gote, and to which there was

a secret passage from the earl’s bedcharnber. No person was admitted to

Smith’s workshop but the earl; and the circumstance of his being often

heard working during the night, raised suspicions that some secret work

was going on which could not bear the light of day. The mystery was at

last disclosed by an inundation of counterfeit coin in Caithness, Orkney,

Sutherland, and Ross, which was first detected by Sir Robert Gordon,

brother to the Earl of Sutherland, when in Scotland, in the year 1611, and

he, on his return to England, made the king acquainted therewith. A

commission was granted to Sir Robert to apprehend Smith, and bring him to

Edinburgh, but he was so much occupied with other concerns that he

intrusted the commission to Donald Mackay, his nephew, and to John Gordon,

younger son of Embo, whose name was jointly inserted in the commission

along with that of Sir Robert. Accordingly, Mackay and Gordon, accompanied

by Adam Gordon Georgeson John, Gordon in Broray, and some other Sutherland

men, went, in May, 1612, to Strathnaver, and assembling some of the

inhabitants, they marched into Caithness next morning, and entered the

town of Thurso, where Smith then resided.

After remaining about three

hours in the town, the party went to Smith’s house and apprehended him.

On searching his house they found a quantity of spurious gold and silver

coin. Donald Mackay caused Smith to be put on horseback, and then rode off

with him out of the town. To prevent any tumult among the inhabitants,

Gordon remained behind with some of his men to show them, if necessary,

his Majesty’s commission for apprehending Smith. Scarcely, however, had

Mackay left the town, when the town-bell was rung and all the inhabitants

assembled. There were present in Thurso at the time, John Sinclair of

Stirkage, son of the Earl of Caithness’s brother, James Sinclair,

brother of the laird of Dun, James Sinclair of Dyrren, and other friends,

on a visit to Lady Berridale. When information was brought them of the

apprehension of Smith, Sinclair of Stirkage, transported with rage, swore

that he would not allow any man, no matter whose commission he held, to

carry away his uncle’s servant in his uncle’s absence. A furious onset

was made upon Gordon, but his men withstood it bravely, and after a warm

contest, the inhabitants were defeated with some loss, and obliged to

retire to the centre of the town. Donald Mackay hearing of the tumult,

returned to the town to aid Gordon, but the affair was over before he

arrived, Sinclair of Stirkage having been killed. To prevent the

possibility of the escape or rescue of Smith, he was killed by the

Strathnaver men as soon as they heard of the tumult in the town.

The Earl of Caithness

resolved to prosecute Donald Mackay, John Gordon, younger of Embo, with

their followers, for the slaughter of Sinclair of Stirkage, and the

mutilation of James Sinclair, brother of the laird of Dun, and summoned

them, accordingly, to appear at Edinburgh. On the other hand, Sir Robert

Gordon and Donald Mackay prosecuted the Earl of Caithness and his son,

Lord Berrtdale, with several other of their countrymen, for resisting the

king’s commission, attacking the commissioners, and apprehending Angus

Henriach, without a commission, which was declared treason by the laws.

The Earl of Caithness endeavoured to make the Privy Council believe that

the affair at Thurso arose out of a premeditated design against him, and

that Sir Robert Gordon’s intention in obtaining a commission against

Arthur Smith was, under the cloak of its authority, to find means to slay

him and his brethren; and that, in pursuance of his plan, Sir Robert had,

a little before the skirmish in Thurso, caused the earl to be denounced

and proclaimed as a rebel to the king, and had lain in wait to kill him;

Sir Robert, however, showed the utter groundlessness of these charges to

the Lords of the Council.

On the day appointed for

appearance, the parties met at Edinburgh, attended by their respective

friends. The Earl of Caithness and his son, Lord Berridale, were

accompanied by the Lord Gray, the laird of Roslin, the laird of

Cowdenknowes, a son of the sister of the Earl of Caithness, and the lairds

of Murkle and Greenland, brothers of the carl, along with a large retinue

of subordinate attendants. Sir Robert Gordon and Donald Mackay were

attended by the Earl of Winton and his brother, the Earl of Eglinton, with

all their followers, the Earl of Linlithgow, with the Livingstones, Lord

Elphinston, with his friends, Lord Forbes, with his friends, the

Drummonds, Sir John Stuart, captain of Dumbarton, and bastard son of the

Duke of Lennox; Lord Balfour, the laird of Lairg Mackay in Galloway; the

laird of Foulis, with the Monroes, the laird of Duffus, some of the

Gordons, as Sir Alexander Gordon, brother of the Earl of Sutherland, Cluny,

Lesmoir, Buckle, Knokespock, with other gentlemen of respectability. The

absence of the Earl of Sutherland and Houcheon Mackay mortified the Earl

of Caithness, who could not conceal his displeasure at being so much

overmatched in the respectability and number of attendants by seconds and

children, as he was pleased to call his adversaries.

According to the usual practice on such

occasions, the parties were accompanied by their respective friends, from

their lodgings, to the house where the council was sitting; but few were

admitted within. The council spent three days in hearing the parties and

deliberating upon the matters brought before them, but they came to no

conclusion, and adjourned their proceedings till the king’s pleasure

should be known. In the meantime the parties, at the entreaty of the Lords

of the Council, entered into recognizances to keep the peace, in time

coming, towards each other, which extended not only to their kinsmen, but

also to their friends and dependants.

The king, after fully

considering the state of affairs between the rival parties, and judging

that if the law were allowed to take its course the peace of the northern

countries might be disturbed by the earls and their numerous followers,

proposed to the Lords of the Privy Council to endeavour to prevail upon

them to submit their differences to the arbitration of mutual friends.

Accordingly, after a good deal of entreaty and reasoning, the parties were

persuaded to agree to the proposed measure. A deed of submission was then

subscribed by the Earl of Caithness and William, Lord Berridale, on the

one part, and by Sir Robert Gordon and Donald Mackay on the other part,

taking burden on them for the Earl of Sutherland and Mackay. The arbiters

appointed by Sir Robert Gordon were the Earl of Kinghorn, the Master of

Elphinston, the Earl of Haddington, afterwards Lord Privy Seal of

Scotland, and Sir Alexander Drummond of Meidhop. The Archbishop of

Glasgow, Sir John Preston, Lord President of the Council, Lord Blantyre,

and Sir William Oliphant, Lord Advocate, were named by the Earl of

Caithness. The Earl of Dunfermline, Lord-Chancellor of Scotland, was

chosen oversman and umpire by both parties. As the arbiters had then no

time to hear the parties, or to enter upon the consideration of the

matters submitted to them, they appointed them to return to Edinburgh in

the month of May, 1613.

At the appointed time, the

Earl of Caithness and his brother. Sir John Sinclair of Greenland, came to

Edinburgh, Sir Robert Gordon arriving at the same time from England. The

arbiters, however, who were all members of the Privy Council, being much

occupied with state affairs, did not go into the matter, but made the

parties subscribe a new deed of submission, under which they gave

authority to the Marquis of Huntly, by whose friendly offices the

differences between the two houses had formerly been so often adjusted, to

act in the matter by endeavouring to bring about a fresh reconciliation.

As the marquis was the cousin-german of the Earl of Sutherland, and

brother-in-law of the Earl of Caithness, who had married his sister, the

council thought him the most likely person to be intrusted with such an

important negotiation. The marquis, however, finding the parties

obstinate, and determined not to yield a single. point of their respective

claims and pretensions, declined to act farther in the matter, and

remitted the whole affair back to the Privy Council. During the year 1613

the peace of Lochaber was disturbed by dissensions among the clan Cameron.

The Earl of Argyle, reviving an old claim acquired in the reign of James

V., by Colin, the third earl, endeavoured to obtain possession of the

lands of Lochiel, mainly to weaken the influence of his rival the Marquis

of Huntly, to whose party the clan Cameron were attached. Legal

proceedings were instituted by the earl against Allan Cameron of Lochiel,

who, hastening to Edinburgh, was there advised by Argyle to submit the

matter to arbiters. The decision was in favour of the earl, from whom

Lochiel consented to hold his lands as a vassal. This, of course, highly

incensed the Marquis of Huntly, who resolved to endeavour to effect the

ruin of his quondam vassal by fomenting dissensions among the clan

Cameron, inducing the Camerons of Erracht, Kinlochiel, and Glennevis to

become his immediate vassals in those lands which Lochiel had hitherto

held from the family of Huntly. Lochiel, failing to induce his kinsmen to

renew their allegiance to him, again went to Edinburgh to consult his

lawyers as to the course which he ought to pursue. While there, he heard

of a conspiracy by the opposite faction against his life, which induced

him to hasten home, sending word privately to his friends—the Camerons

of Callart, Strone, Letterfinlay, and others--to meet him on the day

appointed for the assembling of his opponents, near the spot where the

latter were to meet.

On arriving at the appointed rendezvous,

Lochiel placed in ambush all his followers but six, with whom he advanced

towards his enemies, informing them that he wished to have a conference

with them. The hostile faction, thinking this a favourable opportunity for

accomplishing their design, pursued the chief, who, when he had led them

fairly into the midst of his ambushed followers, gave the signal for their

slaughter. Twenty of their principal men were killed, and eight taken

prisoners, Lochiel allowing the rest to escape. Lochiel and his followers

were by the Privy Council outlawed, and a commission of fire and sword

granted to the Marquis of Huntly and the Gordons, for their pursuit and

apprehension. The division of the clan Cameron which supported Lochiel

continued for several years in a state of outlawry, but, through the

influence of the Earl of Argyle, appears not to have suffered extremely. |