|

PREFACE

THE writing of a preface

provides an author with a convenient opportunity to do several things which

he regards as more or less important. It enables him to explain the plan he

has adopted in the pages that are to follow; to apologise for shortcomings

that he, probably more than any other, is conscious of; and to acknowledge

his indebtedness to friends who have helped him with information or with

words of encouragement and counsel. Under the first of these heads a few

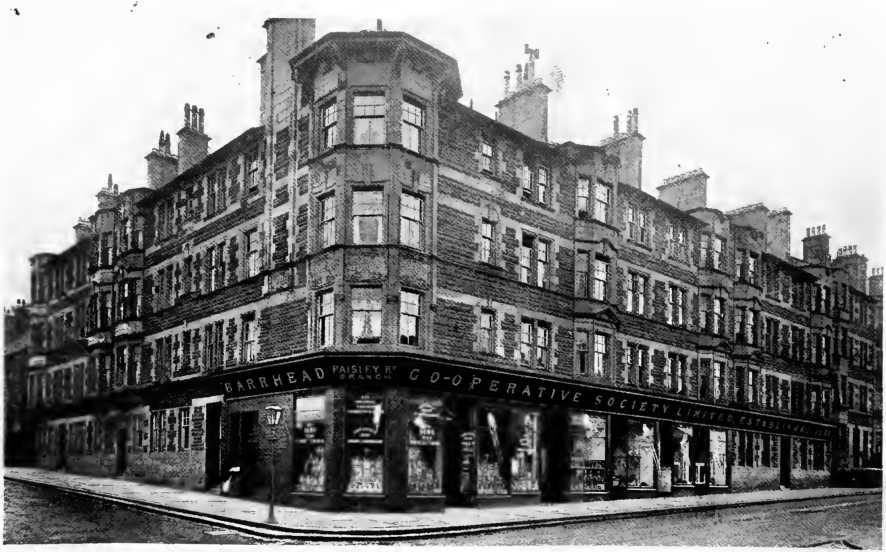

words seem necessary. In preparing this' historical sketch of the formation

and development of Barrhead Co-operative Society the writer has kept

steadily in view the purely local character of his commission. There was

frequent temptation—particularly in the earlier chapters to widen the scope

of the work into a consideration of industrial history in the century

preceding the birth of Co-operation, and of the industrial conditions amid

which the new movement was born. It would have been easy, and in some

respects simpler, to have dipped into the wider Co-operative movement, and

to have shown how great was the army in which Barrhead Society was a

marching unit. But this temptation was successfully resisted, and there has

been strict attention to the local propaganda and the local men, with no

reference to the larger issues unless where such seemed essential.

An effort has been made to

present a clear and fairly definite picture of the Barrhead in which our

fathers lived, and of the social conditions under which they did their

pioneer work for Co-operation. The aim has been to record all the important

steps of the Society’s development, and regret may be expressed that the

need for keeping the book within reasonable limits has necessitated the

exclusion of material for which the writer would fain have found space. As

far as possible, every incident narrated and every fact asserted has been

verified ; and the determination to use only what was unmistakable has

caused the omission of not a few items that would have proved interesting,

but the authenticity of which appeared to be doubtful.

The task has been no light

one, for it involved a great deal of burrowing amongst old records, and it

entailed much interviewing of the yet remaining actors in the historical

pageant which was to be depicted. It meant also the gathering together of a

mass of material far beyond actual requirements, so that the most important

and most interesting portions might be selected. Against this, however, is

to be set down the fact that the work was of a congenial character, and

brought with it a pleasure of a very deep kind. In particular, there has

been a real and heartfelt satisfaction in being permitted to preserve, even

in a fragmentary way, the memories of the able and devoted band of workers

whose efforts created and sustained the young society.

Apologies sometimes savour of

the hypocritical; and, to avoid falling into this error, we will make no

excuses beyond remarking that, whatever faults the critic may point to, will

not, at anyrate, spring from carelessness or want of desire to present the

story of our Society in a reliable and interesting fashion. It will he with

the readers of the book to determine in how far the written record is worthy

of the subject.

In the matter of thanks it is

impossible to indicate all those who deserve to be named. To Mr William

Maxwell we are indebted for information and for a perusal of Mr M'Innes’s

journal, the first Scottish Co-operator. Thanks are also due to Mr Mallace,

of St Cuthbert's, Edinburgh; to Mr A. B. Weir, for assistance and advice; to

Mr James Maxton, M.A., who kindly undertook the correction of the proofs; to

Mr Thomas Dykes, to whom I am indebted for valuable assistance in the

compilation of statistics; and, last, but not least, to the members of the

Jubilee Committee, for their initial confidence in placing the task in the

writer’s hands, and for their continued encouragement and kindness during

the progress of the work.

R. M.

May 1911.

CONTENTS

Chapter I. 1860-61 .

Establishment of the Society

Chapter II. Condition of Barrhead about 1860

Chapter III. 1861-71 : Early Days of the Society

Chapter IV. 1871-81 . Rapid Progress

Chapter V. 1881-91 . Continued Advance

Chapter VI. 1891-1901 . Further Progress

Chapter VII. 1901-11 : Our Own Times

Chapter VIII. Barrhead’s Contribution to the General Movement

Chapter IX. The Pioneers of the Society

Chapter X. The Educational Department

APPENDICES.

Presidents of the Society

Secretaries of the Society

Treasurers of the Society

Barrhead Representatives on S.C.W.S. Board

Barrhead Representatives on Committee of Renfrewshire Conference Association

Admission Lines granted for various Institutions during 1910

Barrhead Representatives on the “Scottish Co-operator" Newspaper Board

Capital Account of Society at December 1910

Statistics of Progress, 1861-1911

Jubilee Celebration Arrangements

Wholesale Co-operation

in Scotland

The Fruits of Fifty Years' Efforts (1868-1918) (pdf)

ScotMid

The Edinburgh based Co-operative society

The People's Year Book

An annual of useful information prepared by the Co-Operative Press Agency

PREFACE

IT is not possible to compile a work of this

character at present without being seriously affected and handicapped by

war-time conditions. There are not the facilities there were prior to 1914

for obtaining up-to-date statistics, whilst many topical matters with which

we should like to have dealt are now characterised by such frequent and

rapid changes that they lose much of their use and value before they can be

conveyed to the public through the medium of a year book. We have had,

therefore, to omit features which would form a permanent asset to an annual

volume like the one we now place before you, and hope to develop from year

to year, especially as prices of printing materials approach a normal level.

We have always felt that a year book of helpful and essential information on

co-operative and allied subjects was needed, and in our first effort we have

to regret several omissions which war-time circumstances and regulations

have compelled us to make. We trust to remedy this defect, however, in

future. In our first year of publication we were anxious to give an

intelligent, but not too ponderous, survey of the co-operative activities of

Europe, also in countries outside the Continent, and, although we have had

to make important erasions with regard to the historical growth of the

co-operative idea at home and abroad, we present a compilation of facts and

figures on world-wide co-operation which we do not remember having been done

before so comprehensively. In view of the intercommunication between

countries being at present difficult and unreliable, and impossible in some

cases, this has entailed considerable research in foreign newspapers and

periodicals, particularly with regard to up-to-date figures. But, whilst we

have endeavoured (and hope to do more in subsequent editions) to provide

information of a general style which may be useful to speakers, writers,

members of public authorities and committees, also all seekers after facts,

we have realised how much space could be occupied with the world activities

of co-operation alone. The plan of co-operation that began at Rochdale has

now extended and been established—in direct or modified forms—in nearly all

the civilised nations of the earth, and a mere statistical annual record

(bald and fleshless) would itself make up a very weighty and cumbersome

volume.

We have, nevertheless, varied our pages with series of figures and concrete

descriptions touching social, political, economic, industrial, and domestic

affairs. Figures dealing with wages, prices, capital, production,

consumption, labour, trade unionism, and a host of other kindred matters,

including the industrial battlefield and the field of sport, are also

encompassed. We hope our compilation will meet with your approval as being

informing and as a work of reference. For next year, to enlarge its

usefulness, we shall welcome criticism and suggestions.

THE EDITOR.

1918 - First Year of

Publication

1919 - Second Year of

Publication

The National Kitchens Movement

THE establishment of national kitchens and

restaurants is one of many measures so accordant with commonsense and public

utility that the very idea of such in normal times was scouted as rankly

Utopian and as altogether incompatible with the conditions of progress in

the best of all possible worlds. In the general bouleversement of

stereotyped ideas brought about by the war, however, the Utopianism of the

pre-war period has become the practical politics for to-day, and probably

for to-morrow and the day after. When Governments have so far descended from

their Olympian altitudes as to provide us with daily bread, national tea and

sugar, and standard clothing, and concern themselves with our rations of

fuel and wants of all kinds, the circumstance may be regarded as an outward

and visible sign of a far-reaching change of conception with regard to

social affairs and to the relations of the State and to the nation at large.

For years in succession the trend of events has been to impress the nation

with the conception that the public welfare is the supreme law, and that the

State is an essential factor in the promotion of the general weal: and

whilst numerous institutions can only be justified as war-measures, others

have shown themselves of such public utility as to ensure the probability of

their permanence when peace-time comes round. National kitchens and

restaurants may be said to rank in this category.

In view of the success of the movement, due credit must be given to the late

Lord Rhondda for adopting a good idea, and for establishing the National

Kitchens Division of the Food Ministry and so setting the movement

officially going and giving it a national status. Since then we have had the

Food Ministry carrying on a public campaign on behalf of Food Kitchens,

where formerly it was members of the public who had to institute a campaign

to secure attention to the possibilities realisable by the methods of public

organisation.

The Organisation and Aims of the Movement.

To-day, local authorities are endowed with the authority and the means to

set up National Kitchens on the public behalf; but the circumgyration

required to bring all this about is indicated by the details recorded by the

Assistant Director of the National Kitchens Division:—

Lord Rhondda believed in decentralisation. He believed in giving a local

authority power to manage its own affairs. In regard to kitchens, power was

given to all local authorities to establish and maintain kitchens, and

authority was vested in them to delegate any of their powers to any

committee that they might appoint. The Local Government Board were

approached, and they also issued an Order to local authorities authorising

them to use money from the rates if necessary for the establishment and

maintenance of kitchens. Up to that point the position was perfectly clear

Then came the question of the capital cost. The Treasury were approached

several times and eventually granted two concessions. The second was very

advantageous and was transmitted to all local authorities in the country. It

was that the Ministry would advancte the total capital cost of the kitchens

as a loan free of interest, to be repaid in equal annual instalments spread

over ten years.

The policy of the Ministry was then to bring home to the local authorities

exactly what they should do. Steps were taken by letter, by circular, and b\

personal interview, to explain the details of the various Orders and the

methods by which the Ministry considered the kitchens should bo run. It was

laid down as a cardinal principal that the kitchens worn to be

self-supporting and run as a business proposition, and there was to be no

air or semblance of charity about them at all. The quality of the' food to

be. supplied was one of the most important questions to lx< tackled; others

worn to avoid the mistakes of the past, to avoid anything in the nature of

glorified soup kitchens, and to avoid the faulty methods apparent in the

German kitchens, where food is supplied in bulk, so that nothing short of

starvation has driven the German people to the kitchens. Our idea was that

everybody in this country was entitled to facilities for getting good food

in national kitchens, regardless of tho individual's means, and that was one

thing insisted noon in the training of cooks and supervisors who had to take

charge of the kitchens.

One of the ideas of the National Kitchens Committee was thal through the

medium of the kitchens, if they were properly run, people—not only the

customers, but also the numbers of small caterers throughout the country

might be brought to see that it was possible to give people appetising and

nourishing food at a price that would enable them to make a profit, and

still be reasonable to tho customers.

The National Kitchens Division

took up the standpoint that, them was no reason why the working-olasses

should not lie better fed than they were now. The Ministry felt that it

could be done, and by setting up some kitchens which worn run entirely by

the department, they had proved that it can be done on a commercial basis of

making a profit. They frequently received letters from different parts of

the country saying that there was a great demand for national kitchens in

that, particular area. If they had an official available they sent him down

to-remind the local people of the powers which they had got, and did_ all

they could to induce those people to put their powers into operation.

The Need of Public Initiative

With the necessity of public initiative, as emphasised by the Assistant

Director of the National Kitchens Division, all will agree:—

But after all, the success of the development of the national kitchens as a

business proposition depended entirely upon the public. It was strong public

opinion which enabled them to be started, and it was public opinion and

action which would enable them to be run successfully after they were

started, so that in the case of any particular trade or area where there was

a distinct need for cooked food that was not at present available, the first

step was to move the local authority. At the same time they were dealing

with the local authority, they could deal with the Ministry.

London Experiments.

The national kitchens, established as models by the Ministry of Food and by

way of experiment, have proved an unqualified success. Thus, with regard to

the Kitchen at Poplar, it was stated after the experiment had been tried for

three months that the Kitchen had been a success from the very beginning;

every week showing a balance of income over expenditure, and the last Beck a

profit (as ascertained for municipal purposes) equal to over 50 per cent, on

the capital outlay; whilst evidence of the popularity of the Kitchen is

afforded by the fact that from 1,000 portions per day served in the first

part of the period named the number increased to over 2,300 before the end

of three months. The scale of charges is indicated by the following

particulars:—

Soup, Id. per half-pint, and per pint, l½d. Cooked meat, entrees, patties,

pies, puddings, or slices from the joint, half a coupon, 4d. and Patties,

&c., 4d. each.

Two tickets for half a coupon available on different days.

Vegetables, 1d. per portion.

Fish, 3d. per portion. -

Vegetarian dishes, 3d. per portion.

Sweets, 4d. per portion.

Cup of tea and scones, 1d.

Coffee, 1d. per cup.

Scones, 1d. each.

Bread and butter, 1d. per slice.

Jam, 1d. per portion.

Pickles, 1d. per portion.

A success even greater than that of the Poplar Kitchen has been the national

restaurant established in New Bridge Street, London, by the Ministry of

Food. During the three weeks ending on August 24th, the net prolit amounted

to £50. 14s. 5d. for the first week, to £70. 13s. 9d. for the second, and to

£73. Os'. 4d. for the third: deductions being made for full rent, management

charges, reserves for renewals, interest on capital at 5J per cent, and

depreciation at 10 per cent, to arrive at net profit: " The rate of £70 per

week, which appears to be maintainable, would be equal to 70 per cent per

annum on the capital outlay, and would repay this within eighteen months.”

During the third week the number of persons served with meals reached

15,525; l\d. being the average receipt for each meal, while the cost worked

out at a trifle under 6£d. after allowance for all charges—the resultant net

profit being 1.1½d. per meal.

Conditions of Success.

From the experience gained in the Poplar enterprise, the Ministry of Food

has emphasised the following conditions as essential to success:—

The premises must be in a good position, and not in a back street, nor in a

basement which necessitates descending many steps to arrive at the kitchen.

The interior must be bright and attractive.

The plant and equipment must be modem and efficient, and not a collection of

old gas stoves.

The cooks and the rest of the staff must bo suitably attired.

The menu must be varied, and the food of the best quality, prepared by

experienced cooks who can produce the best results in the most appetising

and attractive form, regard being had at all times to nutritive values.

Granting these conditions, it is possible for local authorities to seeure

such benefits and advantages as a national profit in the saving of food and

fuel, a municipal profit whieh may be applied in affording additional

quantities of cooked food, a health profit in the provision of better food

for the people, and an individual profit in the saving of time and money to

the patron.

The Growth of the Movement.

Following on the London experiments, the plans of the Ministry of Food in

September last embraced the establishment of national model restaurants in

Birmingham, Bristol, Cardiff, Glasgow, Leeds, Manchester, Newcastle, and

Brighton. And how far the movement had grown by that period is indicated by

the official estimate of 623 kitchens and restaurants serving approximately

a million portions of food per day, and by the fact of schemes for about 150

more having been approved or being in course of preparation, London coming

at the head of a lengthy list with schemes for an additional 36, Yorkshire

next with schemas for 20, and Nottinghamshire the third with plans for 22.

All the same, circumstances clearly show that infinitely more might be done.

When one considers the huge industrial areas in which no effort has yet been

made, one realises once again the passive resistance to public enterprise

characteristic of local authorities preponderantly representative of

profiteering interests—a resistance which nothing can overcome but

uncompromising pressure on the part of the public, in which connection it is

clearly the duty of the local labour movement everywhere to give the public

a lead.

1920 - Third Year of

Publication

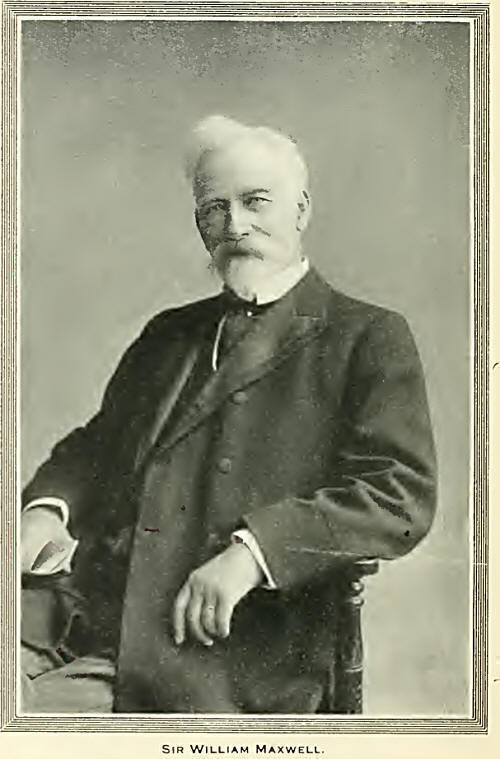

SIR WILLIAM MAXWELL

AS a tribute to his work for co-operation,

nationally and internationally, Mr. William Maxwell was raised to the rank

of knighthood on August 13th, 1919. For a generation Sir William has been

one of the most familial figures in British co-operation, and for a long

time has been well known in some of the co-operative centres on the

Continent. He carries the honour with singular grace and dignity, but,

having attained his seventy-eighth year, he is no longer as active in the

great movement to which he has devoted his time and ability. During his

remarkable co-operative career he has travelled widely, and sown the seeds

of co-operation among people of other lands.

Sir William was born in Glasgow in 1841, and comes of an old Scottish family

who had been hardy tillers of the soil and, incidentally, fighters for their

clan or cause. He served his time as a coach painter, having attained

considerable technical skill by the time his apprenticeship had terminated.

He was a workman of an artistic type, and had knocked about the British

Isles before he began to settle down to co-operation in 1864. First, he

became a member of St. Cuthbert’s Society, Edinburgh—in fact, more than a

mere member; he was enthusiastic, and did a deal of propaganda. Before

attaining the age of forty he was elected a director of the Scottish

Co-operative Wholesale Society (in 18S0); nine months later he became the

president, and maintained the confidence of Scottish co-operators in this

leading position till his retirement in 1908.

With a wide outlook, he devoted bis energy to the constructive work of the

S.C.W.S., and was at the same time an eloquent advocate on the platform.

Perhaps one of his greatest practical achievements was the advancement of

the group of factories at Shieldhall. whence co-operative stores in Scotland

are supplied with a variety of useful goods.

He has been a great believer in the will of the people, and was one of the

pioneers in the agitation to press co-operators to develop a political

consciousness. He had a wide knowledge of the co-operative movement, for

which his determination and sincerity never seemed to flag. He was a source

of inspiration to younger men. To him-cooperation knew no barriers, and his

breadth of mind and outlook fitted him admirably for the spread of the

principle of co-operation internationally. He was president of the congress

of the International Go-operative Alliance at Cremona (1907). Hamburg

(1910), and Glasgow (1913). He has been a member of the Executive Council of

the I.C.A. since 1901, and his position as president of the Alliance has

given him a distinct place in international co-operation, which he regards

as one of the greatest peace forces in Europe.

1921 - Fourth Year of

Publication

1922 - Fifth Year of

Publication

|