|

Strength of the Society in

1861—Primitive Arrangements—Supply of Bread—Fleshmeat—Boots and Coal—First

Quarterly Report—First Dividend—Successes and Trials—Bad Butter and Dear

Sugar— Apathetic Members—Bonus to Workers—Trouble with First Salesman

—Appointment of Second Salesman—Second Shop—Increase of Capital—Credit and

Menage System—Purchase of First Horse— Successive Shopmen.

“Some of the objects of

Co-operation are, to economise the necessary expenditure of the working

class by dispensing with the unprofitable labour and capital that stand

between the producer and the consumer, to gain access to the purest and

cheapest markets, to afford commercial instruction to the people, to give

opportunity for developing the intellectual and moral faculties, to

inculcate the practice of prudential virtues, and thereby create higher

aspirations and fit men for nobler aims in life.” —(From nth quarterly

report of Barrhead Co-operative Society.)

STRENGTH OF THE SOCIETY, 1861

AT the end of our first

chapter we left the little shop at 95 Main Street with its shutters newly

taken down, the shopman behind the counter with his sleeves up, and the

committeemen all hopefully yet anxiously waiting the first results of their

bold experiment. On the day the shop opened, the Society was in the position

of having fifty members and capital amounting to £70—all of which was sunk

in shop fittings and a small stock of groceries. It was a very humble

beginning ; and a very small matter—the neglect of the members or a little

carelessness on the part of the managers—might have meant its ruin. But once

it had got fairly launched, the new Society went steadily on without a

single setback worth speaking of. Doubtless there were moments of anxiety,

but of these we find no mention in the chronicles of the period. On the

contrary there were many things to hearten the pioneers, and we can readily

understand with what joy the report would be received at the end of six

weeks that the membership was increasing and that the weekly drawings for

this period averaged £36,14s. From the first moment of the Society’s

existence the directors face the difficulties that arise in a practical

spirit which commands success.

PRIMITIVE ARRANGEMENTS

Many of its arrangements are,

of course, of the most primitive character, and they are often such as we

cannot look back upon without a smile. Reference has already been made to

the conditions attaching to the appointment of the salesman, and we find

such matters as the purchase of a “ gamel ” for potatoes and the putting in

of a stock of soft goods—to the extent of one piece of moleskin and one

piece of flannel—forming the subject of a very anxious debate. That item “

one piece of moleskin ” seems to indicate that the moulders of Messrs Smart

& Cunningham, who had so much to do with its formation, were still pushing

it forward. The bread supply gives trouble at an early stage, and at the

third meeting following the opening of the shop the committee encounters a

serious difficulty in regard to the delivery of the “ staff of life ” to the

West Arthurlie members. Much discussion finally results in these members'

being asked to appoint one of their own number to receive the bread from the

van in a slump lot, “ take note of each member’s consumpt, and hand the list

to the salesmen to be charged against each individual on the Saturday.” One

can perceive all the elements of trouble here, and, as might have been

expected, the proposed arrangement proved unsatisfactory; and a week later

it was amended so “ that each member arrange with the salesman what quantity

he wants left, and pay at the end of the week.”

SUPPLY OF BREAD AND FLESHMEAT

It will naturally be asked

how it comes that the Society has so early managed to arrange a van service

of bread for its members. The explanation is that the committee made terms

with a local baker to supply bread to the members and send in his account to

the Society. In the years immediately following, this method gave rise to a

great deal of worry and annoyance, first one baker being tried and then

another; but finally “ tokens ” were introduced, and the custom arose of

permitting the members to purchase bread by means of these tokens from whom

they pleased, the bakers being afterwards paid by the Society. In a somewhat

similar way the committee early tackled the question of supplying members

with butcher-meat. Competitive offers were taken from local fleshers, and

the late Mr John Clark was the first to secure the Society’s trade, his

offer of 2S. per £ discount being accepted against one of is. per £ from Mr

William Craig. This Mr Craig, it may be interesting to point out, at that

time a flesher in Main Street, was afterwards the owner of the Cogan Street

Weaving Factory, and as such was well known throughout our district. It was

part of the arrangement that no dividend was allowed to members on their

butchermeat purchases. As can be understood, this proved anything but

satisfactory; and after several spasmodic attempts to put it on a better

basis, the arrangement was finally abandoned.

BOOTS AND COAL

In like manner, and within

twelve months of its birth, the Society had arranged for the supply of boots

from Mr John Paton, and of coals, first from Mr Alex. Kilpatrick but

latterly from Mr Duncan Ferguson. All this is indicative of a spirit of

enterprise on the part of the first managers, which, we believe, will

scarcely be paralleled, and certainly not surpassed, in the annals of

Scottish co-operation. And the sound sense and business capacity of the men

who were at the head of its affairs is proven by the fact that these

courageous experiments were made with at least partial if not always

complete success, and that they were so safeguarded as to entail no loss or

injury to the young organisation.

FIRST QUARTERLY REPORT

The end of the first quarter

was naturally awaited with great anxiety, and the committee, on 6th August

1861, is very pleased to report a slight profit. It is too small, however,

to permit the declaration of a dividend, and is accordingly carried forward

as a small nest-egg for the second quarter. By the second of August we have

climbed so far into a settled condition that it becomes advisable to insure

the stock for £200. Two months later (on 8th October) the directors declare

that “ sensible of the growing business of the Society, the time has now

arrived for the appointment of a boy to assist the salesman,” and Alexander

Stark, son of the secretary, is selected for the situation.

FIRST DIVIDEND

On the 5th November 1861 the

second quarterly meeting is held, and the directors are in the proud and

happy position of declaring their first dividend of is. id. per £, and of

reporting at the same time that the fifty members of the opening have now

increased to 100, and the £70 of capital has grown to £130. Doubtless there

have been many proud moments in the history of the Society, and it must

often have happened that the president for the time being felt a rich glow

of pleasure when called upon to intimate some increase in trade or profit;

but we can well believe that in the whole records of the Society there could

be no prouder moment and no happier president than Mr Adam Crawford when it

fell to his lot to announce that modest dividend of 1/1 and that increase of

100 per cent, on the capital of the members. The practical and far-sighted

wisdom of these pioneers is exemplified also in a motion, brought forward at

the same meeting by two members of committee, to put aside 2J per cent, of

the profits as the nucleus of a reserve fund. It is true that the motion was

defeated by a small majority, but it shows unmistakably that present success

had not blinded the eyes of the leaders to the necessity for making sure of

that success being built upon solid and secure foundations.

CONTINUED SUCCESS AND TRIALS

Continuing their career of

prosperity, the committee, by the middle of December, decide to take the

empty house on the ground flat adjoining the shop. This is to be used

chiefly for directors’ meetings, but also as a land of auxiliary store for

the increasing quantity of goods which they find it necessary to purchase.

Already they are beginning to feel the pinch of small premises, and it is

agreed to take down the partition which divides the shop in two in the hope

that this will permit of more accommodation. So far we have spoken only of

the triumphs and successes which came in that first six months, but no one

who knows human nature—and shall we say particularly co-operative human

nature—will run away with the idea that the lot of the committee was one of

unbroken happiness, or that they slept upon a bed of roses. They had already

been subjected to a good deal of criticism, they had been troubled in spirit

by those whom Mr Stark in one of his early reports calls “ dividend

co-operators,” and a number of dissatisfied ones had already confessed

themselves disillusioned and had departed with their share of the capital.

Indeed, the managers are feeling the want of capital very much, and on the

declaration of the next dividend they urge members to leave the money in the

treasurer’s hands, and beg those who cannot do so “ to take it in goods and

not in cash.” As an instance of the want of sympathy which had occasionally

to be faced, we may point to an incident in the winter of 1862 when there

was great and exceptional want of work and much distress in the district.

The Cotton Famine Fund was being formed to assist cases of necessity, and

the directors of the Society were prepared to bear their part of the burden

lying upon the community. They accordingly recommended to a special meeting

a vote of £5 to the fund. This the members reduced to £x, and at the

following quarterly meeting a resolution was carried censuring the committee

for its resolution, and declaring that “ the same was contrary to the spirit

of co-operation ! ” All this would, doubtless, be gall and wormwood to those

early apostles of the new movement, burning as they were with an enthusiasm

which only those who have taken part in some great movement in its early

days can fully realise.

BAD BUTTER AND DEAR SUGAR

Practical difficulties also

they are bothered with, and it will not seem strange to those who have had

experience of committee work when we say that one of the first to put in an

appearance was our hoary-headed, old friend " bad butter.” " Bad butter ” is

the cry of the members at more than one of the early general meetings, and

the committeemen are kept on the run trying to satisfy diverse tastes in

that commodity. Another difficulty which worries the directors of that time

is, unlike the butter one, unfamiliar to his successor of to-day. This is

the high price of sugar, coupled with the fact that there is a general habit

amongst grocers of retailing it at or even below cost price. What is to be

done with sugar ? If we sell at a price which will permit of a profit, our

members will almost certainly purchase the article elsewhere. If we sell at

cost, how are we to pay a dividend ? And so, after much anxiety, it is

recommended to the members, and accepted by them, that sugar purchases shall

be entered separately in the books, and no dividend paid thereon. Even then

the managers feel they are working the sugar trade at a loss; and at one

meeting it is solemnly recorded in the minutes that an applicant for

membership is refused admission “ as the applicant is a large consumer of

sugar ”—surely as strange a reason as could well be imagined for keeping any

person outwith the co-operative movement! One wonders who this large

consumer was, what were the reasons for his—or it may have been her—heavy

consumption of sugar, and whether he, or she, afterwards reduced it to such

manageable proportions as to permit of a new application being accepted. It

was only in November 1864, and that after a long discussion at a quarterly

meeting, that the regulation as to paying no dividend on sugar was

withdrawn.

MEMBERS' APATHY

Another, difficulty which

arises is, to our thoughts, somewhat unexpected. One naturally assigns to

the men of an earlier generation the possession of virtues, the absence of

which we deplore in our contemporaries. We are grieved, for instance, at the

want of interest too often shown by members to-day, and, by contrast, we

think of their predecessors as being full of enthusiasm and constantly

animated by a spirit of devotion to duty. It is surprising, therefore, to

find that, not once, but many times, in these early years the monthly and

quarterly meetings had to be abandoned for want of the necessary quorum.

Even when the’ membership has grown to three or four hundred, we still find

in the minutes notices of abandoned meetings. To overcome this, many plans

were suggested. Warders were appointed for the different districts, with a

view to beating up laggard members, and, for a long time, absentees from

quarterly meetings were fined one penny. It is interesting to note in this

connection that the recently established regulation for the production of

the share book on entering the meeting is but the revival of an old custom

of the Society. Each member had to produce his book on entering the hall,

and it was the duty of the two most recently appointed members of committee

to keep the door, see that the rule was obeyed, and make a note of the

number of each book shown, so that the absentees who did not figure on the

list might be fined.

THIRD QUARTER’S DIVIDEND

With the completion of its

third quarter and tne repetition of the dividend of i/i, the Society may be

said to have got fairly settled down. The success of the second quarter, it

might have been argued, had been due to some fluke or to an error in

bookkeeping, but a repetition on the same lines and at the same figure

plainly indicated that Barrhead Co-operative Society had come to stay. From

this time onward we find record of continual additions to stock, and there

is a constantly increasing stream of new members. The second

balance-sheet—the first one showing a dividend—was printed; but, on the

preparation of the third, it is considered too expensive to have this done

each time, and it is decided that only every alternate quarter’s report be

printed. Whilst we are touching upon dividends, it may be worth while noting

that in the earlier years lower dividends ruled than would be acceptable

to-day. In the fourth quarter the profit showed 1/2 per £, but it was not

until fully ten years after the formation of the Society that a dividend of

2/ was earned and paid. When, in 1867, after a succession of profits ranging

from 1/2 to 1/6, there was a sudden spring forward to one of 1/10, the

committee could not repress the desire to let its vanity find expression in

the report. “This dividend (i/io),” it says, “ is large, and should satisfy

the expectations even of the most sanguine of the merely dividend

co-operators, and especially gratifying will it be to those who are

co-operators on principle.”

BONUS TO EMPLOYEES

It is to be remembered that

from the beginning and, indeed, right on until May 1875, the payment of

dividend on purchases was accompanied by an equivalent bonus on all

emplpyees’ wages. At a meeting in May 1875, a majority of the members

decided against the continuance of the bonus to servants, and the position

then taken up has never been altered, although it has sometimes been called

in question. The decision on that point is an instance of a very complete

change of policy, for at a meeting in June 1867 it was unanimously affirmed

that “ the payment of a bonus on wages was a fundamental principle of

co-operation.”

TROUBLE WITH FIRST SALESMAN

Its speedy and continued

success would seem to have indicated that the Society was fortunate in its

first salesman, but this is hardly borne out by the minutes. John Blackwood

would appear to have been a very capable person, but he seems to have made

the mistake of thinking that the board would be a mere figurehead, content

to look vacantly on at his management, provided he succeeded in producing

profits. Before the first year is out there are evidences of conflict

between the salesman and the committee. He is twice reprimanded for want of

respect towards the directors, and there are repeated complaints that he

pushes certain goods and holds back others which are more sought after by

members. It is therefore decided, in September 1862—sixteen months after his

appointment—to dispense with his services, principally on the ground of his

overbearing manner and disobedience to the directors. The following week Mr

Martin Whyte is appointed to the vacancy, but the first man will not go

without creating a certain amount of trouble. He carries his case before the

following meeting of members, to whom he appeals for justice. He blames

chiefly the boy, Alexander Stark, whom he alleges had been appointed against

his wishes, and personally accuses the secretary of being the direct cause

of his dismissal. The meeting, however, with unanimity, support the

committee, and approve of what has been done. Even then John Blackwood

remains a trouble. He desires, naturally, to withdraw his security at once,

but £50 is more than the Society can afford to pay on short notice. Half of

the amount is paid over in a week or two. There is a good deal of

correspondence, and even threats of legal proceedings from both sides, but

it is not till January of the following year that he finally obtains the

balance due him. And, after all, the last word remains with the salesman,

for he puts the Society to some inconvenience by refusing to grant his

signature to a request that the “ certificate of license ” (probably a

tobacco licence) be transferred from his name to that of the president.

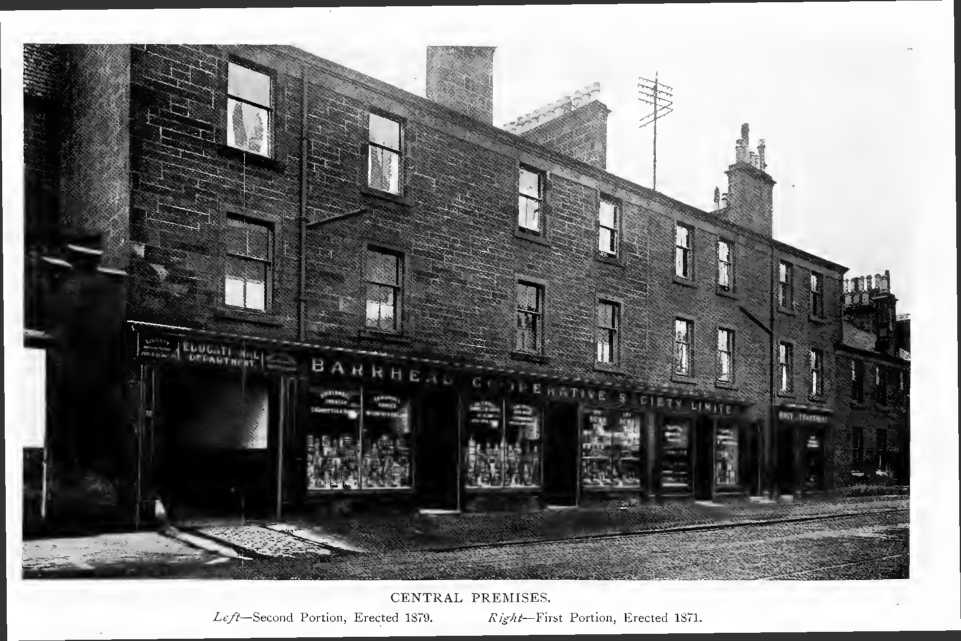

SECOND SALESMAN AND SECOND

SHOP

Within a short time of Mr

Martin Whyte’s appointment additional assistance is required to meet the

growing demands of members. Miss Maggie Whyte is appointed to help in the

shop, at first for three days a week, and latterly on full time. The little

shop is no longer able to satisfy requirements, and after many negotiations

with the proprietor—Mr Gillies, of Cross Arthurlie Hotel—it is finally

agreed to lease a shop then occupied as a public-house at the comer of Bank

Street. The lease is for ten years, with a break at seven; and in May 1864

the Society moves into these larger and specially fitted premises. In the

negotiations which preceded the taking of the new shop the late Mr John

Allan acted as the agent between the Society and the landlord ; whilst the

practical arrangements and fitting up of the shops were left to men whose

names are so familiar to us as those of James Baillie and Thomas M'Cowatt.

INCREASING CAPITAL

At a slightly later period

the Society was beginning to find capital accumulating in its hands, and

there were many anxious discussions as to how this could be remuneratively

employed. A favourite proposal was the establishment of a com mill, and over

and over again/' both in committee and at general meetings, motions are made

as to the desirability of the Society taking up the grinding of grain for

their own use and for sale to others. A few shares had already been taken in

the Paisley Manufacturing Society, and an English company, the Calliard

Flannel Manufacturing Company, had apparently appealed to the directors as a

likely opening, and there were many talks about its prospects, but in the

end no money was invested in the business. Another project which seems to

have had an attraction for them, and

with which they coquetted a

good deal, was that of ham-curing. They frequently bought pigs from members

and others in the district, which they killed and cured for sale, and a

committee was appointed to investigate the subject with a view to commencing

hamcuring on a larger scale; but in the end nothing came of it, and instead

of starting some small productive work of its own the Society was ultimately

content to invest its surplus wealth in the larger undertakings of the

general co-operative movement.

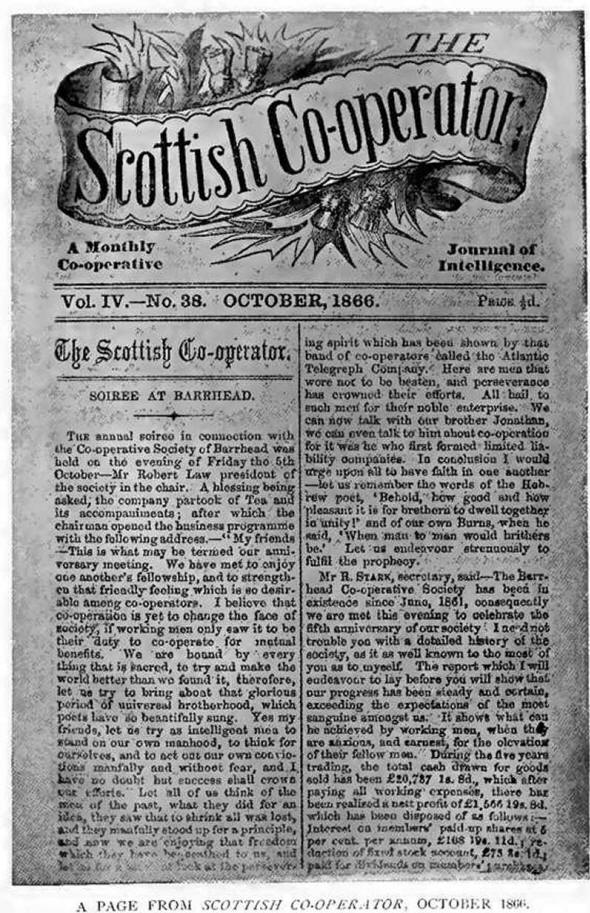

CREDIT AND MENAGES

In the rules drawn up for the

Society, the promoters were careful to insist upon all its trade being done

on the cash system, and on the outside cover of the original rule book stood

the clear-cut statement—“ All Purchases to be paid for on delivery.” Then,

as now, there were members to whom this acted as an impediment to their

desire to be consistent to the Society. The first effort to overcome this

difficulty took the form of a clothing club, which was formed, not through

the Society, but within it, and with its approval. This seems to have been

unsatisfactory; for as early as 1864 we find a discussion on the first

suggestion for the now familiar menage system for the supply of boots and

clothing. It was deferred at that time, the directors plainly indicating

their dislike to anything in the nature of the dreaded credit trading, and

it is some time later that the menage method is adopted. This is not the

place to discuss the much debated question of a strictly cash or of a cash

and strictly safeguarded credit trading, but it will, no doubt, interest

many if we quote the remarks of the old Scottish Co-operator when reviewing

Barrhead Society’s thirty-seventh balance-sheet. The report was a favourable

one, and announced a dividend of i/ii per £. The editor speaks of it,

therefore, in approving terms, but adds—“ We notice, however, an ugly item

of £494 as value for goods owing to the Society. We are aware that this is

incurred in that new mode of credit termed a 'menage,’ but as we hear of

several societies that have met losses from these menages, it will be well

that the directors pay special attention to this matter as the sum gradually

gets to be very large.” The menage system with various modifications has

ever since remained in operation. Either the fears of its opponents have

proved groundless, or the successive committees have heeded the warning to

keep a watchful eye upon the accounts, for we have not heard of any great

loss inflicted by its workings, and, on the other hand, it has probably been

one of the causes of the Society’s steady and increasing trade.

PURCHASE OF FIRST HORSE

From a very early date the

committee aspired to own a horse of its own, and more than once instructions

were asked from the members on the subject. No doubt the members were also

flattered at the thought of possessing their own horse, but they were at the

same time always careful not to commit themselves, and, time after time,

they sent the proposal back to the board for further consideration. It was

only after long thought that the directors could make up their minds to take

the plunge. Finally, in the opening months of 1867, it is definitely decided

to purchase a horse for the Society’s use, and Mr James Williamson, the

treasurer, and “another member ” are appointed to carry out the important

commission. The real story of that first horse transaction is still recited

with gusto by Mr John Lindsay—now one of the two surviving representatives

of the original members of the Society. Mr Williamson and Mr Robert Law, at

that time president of the Society, journeyed to Glasgow, and in the market

there they spotted “ the very article" for their purpose. The bargain was

quickly concluded, and in high spirits they brought their new four-footed

servant home. Committee members and other friends were hastily summoned to

admire the new acquisition, and amongst those who attended was a carter, an

uncle of Mr Lindsay. ' The company was examining the animal in solemn

silence and at a respectful distance, but the carter immediately began a

real' professional inspection. After a few preliminaries, he proceeded to

the important part of examining its mouth. No sooner had he pulled open the

horse’s jaws than “ Man,” he exclaimed, with the characteristic vigour of

the carter, “ the b-has nae tongue.” It was too true ! Whether by disease,

accident, or ill-usage, the fact was undeniable that the horse had no

tongue. What could be done with it ? was the anxious question of an excited

committee. The carter being appealed to, offered to go with the subcommittee

to Glasgow on the next market-day, where he helieved he might sell it. “But

mind ye,” he added, “ ye’ll need to leave the market d-smert whenever the

beast’s sel’t.” The horse was got rid of in this way at some loss, and for

years afterwards the buying of the horse which had no tongue was a standing

joke, relished by the buyers no less keenly because it was against

themselves. Such is Mr Lindsay’s story of the buying of the first horse,

and, reading between the lines, one can find ample verification in the

minutes. On nth February 1867 the purchase is decided upon, and on 18th

February Mr WilHamson reports buying the animal, but the minute immediately

adds “ resolved, unanimous, that we sell the horse as soon as possible, as

it is not fit for our business.”

SUCCESSIVE SHOPMEN

Our record of the events

which may properly be grouped under the general heading, “ Early Days,”

which is given to this chapter will, we think, be brought to a fitting close

if we return for a short time to the shop itself and the successive shopmen

who presided there. Mr Martin Whyte, appointed in 1862, whilst the Society

was still in its first shop, continued in its service until 1866 when he

resigned. At this time the second shop had been occupied for two years, and

trade had shown a very considerable increase. Robert Adam, from Paisley, was

Mr Whyte’s successor, but he resigned in April 1868, and in doing so left

the Society in a somewhat awkward fix. He could not remain longer than the

19th, and his successor, Robert Sturrock, from Greenock, could not come till

the 26th. To make matters worse, the second-hand also intimated his

intention of leaving on the 19th. This man had been making repeated but

unsuccessful applications for an increase of wages, and he apparently

thought this an excellent opportunity to force the hands of the directors.

How to manage for the week pending the arrival of the new man was the

question. Determined not to be beat, the committee accepted the second man’s

resignation, hurriedly appointed a lad in his place, and put in the

treasurer, James Irvine, to assist until Mr Sturrock would arrive. It was

only a few weeks before this that the directors had removed the steadily

increasing stock, of drapery from the grocery shop, and had appointed a Miss

Au.chencloss to take charge of the first drapery department. She also was

pressed into service in the grocery, and by these means the difficulty was

overcome. The new salesman, Mr Sturrock, remained with the Society only a

year, when he was appointed first manager of the newly-formed United Baking

Society. He was succeeded by a Mr Joseph Tait, but this proved an

unsatisfactory choice, and he was dismissed in 1871. His successor was Mr

John Tyndall, the very mention of whose name is sufficient to indicate that

we are approaching much more modem times, for Mr Tyndall will be recalled by

a hundred for one who can remember any of his predecessors. For many years

thereafter he continued in the Society’s service, and was closely associated

with the period of progress and development which followed. |