|

Earlier Co-operative Efforts

in Barrhead—Life and Trade of Town— Growth of Population—The “Capital” of

Barrhead—Construction of the Railway—-Barrhead Races—Intellectual and Reform

Activities— The Truck System—-A Friendly Employer—Influences which Helped or

Hindered Co-operation.

“I hae walked in noble cities

where Life’s fullest pulses beat,

And I ken rare spots of beauty where the sea and river meet;

But abune them a’ I lo’e the vale where Levern hurries doon,

And I ken nae place sae kindly as mine ain grey toon.”

EARLIER EFFORTS

IT has already been pointed

out that Robert Chambers’s article in the Miscellany formed the point round

which the hitherto indefinite aspirations of the early Barrhead co-operators

gathered. But it is not to be thought for a moment that this was the first

intimation that such an intelligent group of men had of .the new movement.

Fugitive references to the Rochdale effort and to co-operative experiments

nearer home were appearing in many of the journals and newspapers of the

period. In the workshops of the district, and particularly in that of Messrs

Smaft & Cunningham, the subject had been much discussed, and about eighteen

months earlier an unsuccessful effort had been made to interest a sufficient

number of men to warrant a start being made. In the interval between that

effort and the new one of 1861, some of the leading spirits had tried their

hand at co-operative buying on a humble scale, and a small chest of tea, a

few pounds of tobacco, some cheese, and other similar goods had been

procured and divided amongst the co-operators, of whom the principals at

this time were Robert Stark, James Baillie, and Robert Law. At a still

earlier date, some years indeed before this, the Levern Victualling Society

had been formed on the joint-stock principle and with all the profits

devoted to capital. In 1861 the Victualling Society was carrying on business

in a shop near the lower end of Main Street. Its manager was Mr John M'Lean,

long afterwards well known throughout the district and for many years a

highly-respected elder of the U.P. (now Arthurlie U.F.) Church. With the

establishment and success of the new Society, the older effort declined and

soon passed away.

EARLY DAYS OF BARRHEAD

Before we consider in more

detail the growth of the Society, it will be well that we should try to gain

some idea of the life and work of Barrhead at this period of its history. It

was in the year 1750 that the first house called “ Bar-head ” was erected.

At that time the villages of Dealstone and Dovecothall had been for a

considerable time in existence, and in 1770 Mr Gavin Ralston laid out and

built the new village of Newtown-Ralston, near what is now Craigheads. By

this time the one house of Barrhead has had a few others added to it, and

with the establishment in 1773 of the first bleachfields, followed by

several printworks and by the Levern Spinning Mills in 1780, the

Notice of Removal or

Dissolution.

40. In case of any alteration

in the place of business or dissolution of the Society, notice shall be sent

to the Registrar of Friendly. Societies seven days before or after such

removal or dissolution, signed, by the Secretary or other principal Officer

of the Society, and aiao by three or more of the Members of the Society.

Construction of

41. In construing these

rules, -words importing the masculine gender shall be taken to apply to a

female; words importing one person or tiring only shall be talcen to apply

to more than one person or thing; and words importing a class shall be taken

to imply the majority of that class, unless there is anything in the context

to prevent such or oomstrucUun,

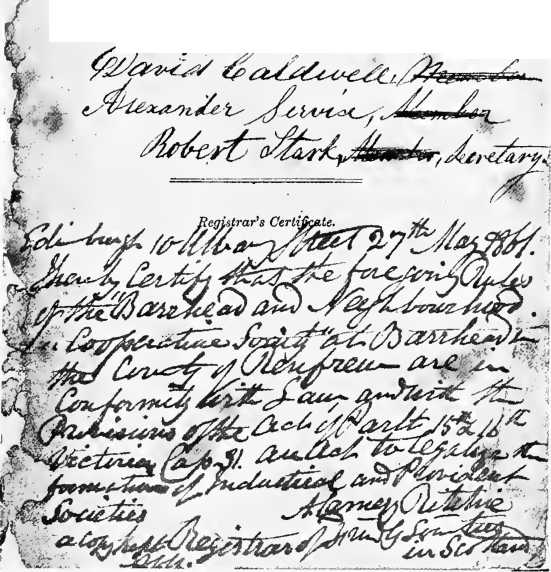

CERTIFICATE OF REGISTRATION OF RULES

population began to grow

rapidly. It is noteworthy that the Levern Mills, which were the second of

the kind to be built in Scotland, can now claim to be the oldest with a

continuous record of work—the first one, which was built at Rothesay, having

long since passed out of existence. Let it be noted here also in passing

that, to the curious in these matters, an evidence of the much taxed

condition of our fathers will be found in the small windows still to be seen

in part of the mill. This was a result of the window tax of that time, a

time when there was also a heavy tax on every copy of a_ printed newspaper,

and when each square yard of printed calico paid to the Government a tax of

3jd. It is recorded that in the year 1830 this calico tax raised from two

out of the many Barrhead p'rintfields a sum of no less than £11,300. At this

time (1830) the industries of the place were bleaching, printing, spinning,

weaving, silk-weaving, net-weaving, and turkey-red dyeing. Some of these

rapidly declined, but most were still in operation, with engineering added,

when in 1861 the Co-operative Society was formed.

GROWTH OF POPULATION

The population, which had

grown to 1,000 in 1800, had risen in 1831 to fully 5,000, this including the

inhabitants of Barrhead, Newtown-Ralston, Grahamston, Dealstone, and

Dovecothall. The form of the village, or rather of the group of villages

named, had undergone many changes, and by 1861 the line of the streets and

the shape of the growing town was not unlike that of the present day,

although much that is now built upon was then vacant ground, and most of the

houses then in existence were very different in construction from those with

which we are now familiar. The buildings were largely of one-storey, with

here and there a more pretentious erection of two-storeys, and in the whole

of Main Street there were only two or at most three buildings which had

attained to the dignity of the third storey. Cross Arthurlie Street was

still more sparsely built upon, and there were stretches of cultivated

fields and country lanes between the houses, whilst most of our side streets

had then no existence.

“CAPITAL OF BARRHEAD.”

In Grahamston and Paisley

Road the one-storey thatched-house still prevailed, but in the former there

was a larger number of two-storey dwellings, and there were also, at its

upper end, the large and, at that time, imposing two-storey tenements, built

by Mr Patrick Graham of the Chappellfield, to accommodate some of the small

army of 700 workers which that extensive bleach-field employed. On the

strength of these larger and more important buildings, the Grahamston people

of that period spoke of their village as “ the capital of Barrhead.” The

fact that the Co-operative Society has chosen Graham Street for the site of

its principal place of business may, perhaps, entitle the district to revive

and retain this ancient boast.

THE COMING OF THE RAILWAY

Up till the year 1848 the

connection of the now thriving town with Glasgow was maintained by means of

the carrier’s cart, the stage coach, and the foot carrier, the latter being

largely employed in conveying small urgent parcels and the newspapers which

were such a necessity for an intelligent and Radical community. With the

completion of the railway, life underwent many changes, and there were also

a number of topographical alterations, the principal of which was the

lowering of Graham Street and Paisley Road to their present levels. The

amount of cutting necessary to effect this may be realised by a reference to

the fact that the older houses in these two streets, which are now reached

by flights of stairs, were built upon what was the original roadway level.

Prior to the erection of the Graham Street and Paisley Road premises by the

Society this difference was still more apparent, for the old thatched

properties, which they displaced and whose foundations were a good twelve or

fifteen feet above those of the present erection, had also been placed on

the old roadway and at the spot where the new road had to be cut down to its

lowest point.

BARRHEAD RACES

The railway brought the town

into closer touch with the outside world, but for a considerable time

Barrhead retained some of its older and more primitive customs. The old “

Barrhead Races ” may be cited as an instance. Until shortly before the

period with which we are concerned these annual races continued to be held,

the actual “ course ” where the racing took place being Main Street, from

Aurs Road to Cross Arthurlie comer—and sometimes the head of Kelbum Street

and back again. On these occasions the roadway on either side was lined with

sweetie stalls, apple barrows, and all the paraphernalia of a country fair.

The “ change-houses ” did a roaring trade, for “ pies and porter ” were the

special treats associated with this event, and the “Jock” who was not

prepared to be lavish towards his “Jenny” in the matter of these delicacies

was regarded as very mean and stingy indeed. For close on seventy years the

races were held in Main Street, but in the fifties this was discontinued,

and they were transferred to a field in Aurs Road where they survived for a

few years longer.

INTELLECTUAL ACTIVITY

From 1800 to 1831 the

population had increased very rapidly., and it continued to grow although at

a much slower rate; by 1861 it was slightly over 6,000, this including, of

course, the inhabitants of Dealstone and Dovecothall. Barrhead was, indeed,

as an old rhymner had called it, “ a thrifty, thriving place,” and this

period was by no means the least thrifty or thriving in its Gareer. It is

not to be thought, however, that its inhabitants, in spite of their energy

in industrial pursuits, had permitted themselves to neglect the more

intellectual duties of life. In the days of Chartism the local weavers and

other Barrhead craftsmen had taken an active share in the agitation, and

amongst the men who afterwards took part in the formation of the

Co-operative Society were some who had carried the pike and had taken part

in the secret drill of those who looked forward to civil war as being the

only way to free themselves and their fellows from the tyranny of the ruling

classes. From this group of Barrhead reformers there is a letter still

extant to William Cobbett, asking him during his tour in Scotland to address

a meeting in Barrhead Secession Church. The reformer was unable to comply at

the time, but promised to do so in the future if opportunity served. The

opportunity, however, never came—at any rate the visit was never made.

MECHANICS INSTITUTE

As a further proof of the

intellectual activity of the people in the district, it may be noted that

the Barrhead Mechanics’ Institute, established in 1825, was the first of the

kind in Scotland, and the second in the kingdom. For eighty years thereafter

this Institute had a history of almost unbroken activity, and its books and

lectures contributed in no small degree to the enlightenment of the

community. Thus the men of 1861, who initiated co-operation, the further

step along the line of social evolution, were either themselves men who had

long lived an active intellectual and reform-loving life, or were the sons

and true successors of such men. It was a time of quick changes. The great

industrial revolution which marked the whole course of the nineteenth

century was gathering force and breaking into its full stride. It swept away

many long-established habits of life and thought, and brought many changes

in its train. It broke up completely the old aristocratic and peasant orders

of society ; and but for the fact that the workers, as a body, were ready to

take advantage of the few opportunities which the new capitalism gave them,

there can be little doubt that this industrial revolution would have had a

very different outcome, and would have fixed upon the toilers an even more

odious form of slavery than that to which it ultimately subjected them.

THE TRUCK ACT

One other thing which helped

materially, at least in Barrhead, to prepare the ground for the seed of

co-operation was the fact that the infamous truck system was still in full

force. Many workers hardly knew what it was to see or handle their own

wages. Most of the shopkeepers had grown so accustomed to the system and to

a book trade that they looked with no favour on the customer who wanted to

pay ready cash. Wages were paid fortnightly or—and this in many cases—

monthly. The workers were tied to certain shops, and before pay-day arrived

the shop books were sent to the works, showing the amount due by each person

employed, and this sum was deducted from his wages and handed to the

shopkeepers. It frequently happened, of course, that instead of there being

anything left to pay over to the unfortunate worker, there was a debit

balance to be carried forward against the next pay-day. The workman had no

redress, and had not even any check against the quantities stated and the

prices charged by the shopkeeper. If he had no money left, and wanted

special articles, such as boots or clothing, he could only procure these

through the grocer with whom his employers had a “ truck ” agreement. It was

a cruel and tyrannical system, and in large numbers of cases the employers

made greater gains from it than the shopkeepers did, since they insisted

upon their pound of flesh in the form of a heavy percentage on the sums they

were called upon to pay over to the dealer. This, of course, the latter

provided against by increasing the cost of commodities to the worker. It was

the usual story of “ wee peerie winkie ” having to pay for all. One local

shopkeeper of that period, who lived to a good old age, has assured the

writer that on a pay-day he, in one little shop, has drawn between £700 and

£800 direct from the offices of the works, and he added significantly: “

These were the days when grand profits were made.”

A FRIENDLY EMPLOYER

Very naturally, the formation

of a society which offered to the worker a means of escape from this

thraldom was met with strong opposition on the part of the employers and of

the shopkeepers. There can be no doubt that this attitude, especially on the

part of employers, did much to restrain the more timid from joining. In some

cases men were given very clearly to understand that it would not be to

their interest to associate themselves with the new movement, and in some of

the works the foremen were particularly active in their opposition.

Fortunately, all the employers were not unfriendly, and it may be worth

while, at this point, putting on record a story which has the merit of being

true, and which is exceedingly creditable to the good sense and broad spirit

of the late Major Henry Heys. It was freely reported that the head of the

South Arthurlie Print Works was strongly opposed to the Co-operative

Society, and some of the foremen in the works were at great pains to keep

the rumour in circulation. This reached the ears of Mr Heys ; and to show

that it was unfounded, and that he looked on the Society with no disfavour,

he promptly became a member, and paid in his £5 of share capital. This sign

of approval from such a quarter was of considerable assistance to the young

organisation, and doubtless encouraged many of the South Arthurlie workers

to join. The story has a pleasant sequel, which seems particularly worthy of

mention. Many years later, at a time when the Society had long got over its

first troubles, objection was raised to some members who had capital

invested with the Society, but were not purchasers of its goods.

After discussion, it was

agreed to intimate to these individuals that they must either withdraw their

capital, and cease to be members, or begin making purchases from the

Society. Amongst those in this position was Mr Heys. He was waited upon by

an official of the Society, and informed that he must either withdraw his

share capital or begin to buy his goods at " the store ” ; but he replied

that there must be some error, as he had no capital in the Society. He was

thereupon reminded of his action in paying in his £5 in the early days of

the Society—an action which had seemingly slipped from his memory—and he was

informed that the sum then lying to his credit was more than double what he

had originally paid. The money was afterwards withdrawn, in conformity with

the decision of the members, Mr Heys remarking that it was one of the best

investments he had ever made.

Such were some of the local

circumstances in the midst of which the Barrhead Co-operative Society was

brought into existence, and such were some of the influences which went

towards the shaping of its destiny. These influences were not all friendly,

but neither were they all hostile. By the help of the friendly ones, and in

spite of the unfriendly, the Society succeeded in getting a firm hold upon

the community, and—as we shall see in our next chapter—entered very quickly

upon a prosperous career unhampered by any serious errors or failures such

as beset the early paths of very many of the societies then springing into

existence. |