|

SECTION I.

GENERAL OBSERVATIONS ON THE

HIGHLANDS AND ISLANDS OF SCOTLAND.

General Features of the

Highlands, paragraph 1.—Landed Property; Population, 2.—Early History of the

Highlands, and Characteristics of the Ancient Highlanders, 3.—Strength and

Distribution of the Clans, 4.—Their Political Relations, 5.—Causes of Change

and Career of Improvements in the Highlands, 6.—Dwellings, 7. —Commercial

Resources, Harbours, and Piers, 8.—highland Societies of London and

Scotland, Sheep and Wool, 9.—Black Cattle, horses, 10.—Wood,11.—Kelp,12.

—British Fisheries, 13.—Herring and Salmon Fisheries, 14.—White Fish,

15.—Game, 16.—Sources of Livelihood; Dress; Language, 17.—Ecclesiastical

History of the Highlands, 18.—Parliamentary or Government Churches,

19.—Episcopacy in Scotland since the Revolution, 20.—Present Ecclesiastical

Statistics of the Highlands. 21.-1tistory and State of Education and

Religious Instruction, 22.—Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian

Knowledge; Gaelic Scriptures; Government Missions, 23.— Erroneous System of

Education till of late years observed, 24.—Edinburgh and Glasgow Gaelic

School Societies, and Inverness Education Society; 'Moral Statistics,

2a.—General Assembly's Educational Scheme Gaelic Episcopal Society; Gaelic

Scriptures, 26.-1'rescnt State of Education and Religious Instruction,

27.—Gaelic Literature, 28.—Highland Music, 29.—General Character of the

Highland Population, 30.

1. IT will save much

repetition in the body of this work, if we begin it with a few general

remarks on the external appearance, history, and statistics of the

Highlands, with some brief notices of the present condition of the

inhabitants and their resources, and such a sketch of the natural history of

the country as is necessary for the use of the Tourist, and which may assist

the recollection of the man of science. The highlands of Scotland, then,

strictly speaking, consist only of the mountainous parts to the north of the

Firths of Clyde and Tay, and the River Forth. Their boundary stretches in a

line from S.W. to N.E., a few miles north of the cities of Glasgow,

Stirling, Perth, and Dundee, and excludes the greater parts of the sea

coasts of Nairn, Elgin, and Banff shires, and the counties on the eastern

coast south of the Moray Firth—all of which were peopled at an early period

by Saxon, Danish, or Flemish colonies ; and hence were separated from the

Highlands which peculiarly composed the territories of the ancient Gaelic or

Celtic tribes. As, however, the whole of Scotland north of the line just

mentioned is commonly regarded as belonging to the Highlands, including the

Hebrides, the Orkney and Shetland Isles, many districts of which, both in

form and population, are decidedly lowland, we shall undertake to guide the

tourist through all the northern counties and islands, with the exception of

the eastern coast south of Aberdeen; and many places also beyond the

Highland boundary, will be at least partially described.

This great tract of country,

as its name denotes, is of a mountainous character. The mountains vary

greatly in elevation as well as form : their greatest height being about

4400 feet, while they often exhibit groups and clusters of nearly uniform

magnitude, sometimes about 1000, sometimes 2000, and occasionally 3000 feet

and upwards above the sea. In general, the principal chains of mountains

extend across the country in a direction from S.W. to N.E., and the larger

valleys which intervene between them have a parallel direction; while the

intersecting openings, or lateral valleys, observe no such regularity. The

eastern side of the north of Scotland for the most part presents a

continuous unbroken line of coast, while the western is indented by

numberless narrow arms of the sea. This latter coast, also, is flanked by

clusters of large islands, of varied aspect, with smaller ones interspersed

among them, forming an almost unbroken breastwork between the ocean and the

mainland ; while the eastern shore, on the other hand, is entirely

defenceless, and exposed to the entire force of the German Ocean. The

mountains of the west coast generally possess a more verdant and less of a

heathery aspect than those in the interior and the opposite shore. Their

acclivities are also more abrupt, and their forms more picturesque. A

further strongly distinctive character between the east and west coasts, is,

that the mountainous ranges in general subside much more towards the former.

The inclination of the surface of the country on this side being thus more

lengthened, its rivers have a more prolonged course, and are consequently of

greater body—as the Tay, Dee, Spey, Findhorn, Beauly, Carron, and Oikel,

with which there are hardly any streams that can compare on the western side

of the island; and several of their estuaries also assume the characters of

extensive firths, while on the west they do not attain such dimensions as,

in any case north of the Clyde, to be so designed. Patches of arable ground

are cultivated in the less elevated portion of the uplands, fertility and

cultivation increasing with the descent of the valleys; and, on the

seacoasts, rich and luxuriant crops are seen gladdening the face of nature.

Except on the eastern shore, however, there is, on the whole, no great

extent of cultivated land. Here the level and sloping tracts are most

extensive: to this side the towns are chiefly confined, and consequently

greater wealth exists to stamp its impress on the scenery, and the exports

of grain and other produce from Caithness and the east coast of Ross and

Inverness-shire are considerable. Native woods, chiefly of pine and birch,

clothe the declivities in many parts of the Highlands, overhanging generally

the banks of lakes and streams; and the planting of hardwood and larch has

of late greatly extended the woodland. The west coast rarely presents any

breadth of wood, though it is occasionally adorned with trees; but on both

sides, and in all parts of the country, the remains of very large trees of

oak and fir are found under gravel banks and in peat mosses.

A surface so diversified necessarily exhibits, within very circumscribed

limits, varieties of scenery of the most opposite descriptions; enabling the

admirer of nature to pass abruptly from dwelling on the loveliness of an

extensive marine or champaign landscape into the deep solitude of an ancient

forest, or the dark craggy fastnesses of an alpine ravine; or from lingering

amid the quiet grassy meadows of a pastoral strath or valley, watered by its

softly flowing stream, to the open heathy mountain-side, whence "alps o'er

alps arise," whose summits are often shrouded with mists and almost

perennial snows, and their overhanging precipices furrowed by deep torrents

and foaming cataracts. Lakes and long arms of the sea, either fringed with

woods or surrounded with rocky, barren, and mossy shores, now studded with

islands, and anon extending their silvery arms into distant receding

mountains, are met in every district ; while the extreme steepness,

ruggedness, and sterility of many of the mountain chains, impart to them as

imposing and magnificent characters as are to be seen in the much higher and

more inaccesible elevations of Switzerland. No wonder, then, that this "land

of mountain and of flood" should have given birth to the song of the hard,

and afforded material for the theme of the sage in all ages ; that its

inhabitants should be tinctured with deep romantic feelings, at once tender,

melancholy, and wild ; and that the recollection of their own picturesque

native dwellings should haunt them to their latest hours, wherever they go.

Neither, amid such profusion and diversity of all that is beautiful and

sublime in nature, can the unqualified admiration of strangers, from every

part of Europe, of the scenery of the Highlands, fail of being easily

accounted for; nor can any hesitate in recommending them to visit the more

remote or unknown solitudes.

[The following sketch, in

this foot-note, of the Geology of the Highlands, may not be unacceptable to

some of our readers:

The great central mass of the

highlands consists of rough old primitive or crystalline rocks—those of

Argyleshire, in the extreme south-west, being chiefly mica and

argillnceous schists, succeeded, on the north, towards Glencoe and

Ben-Nevis, by huge mountains of the most ancient porphyritic or eruptive

rocks. The Lennox, Perth, and Inverness shires, consist, for the most part,

of gneiss rocks, through which granite, in mountain masses and veins, has

protruded in almost every direction—the great central ride of the Grampians

being principally composed of that rock; which, thence descendes, in wide

moorish plateaus, through the heights of Banff and Aberdeen shires, and

projects itself into the German Ocean in the shape of long headlands and

ranges of mural precipices. Ross and Sutherland shires also abound most in

gneiss; but some of their most rugged and picturesque portions—such as those

about Loch Duich, Loch Marge, and Gairloch—consist of mica slate, a rock

which presents a more serrated and deeply-cleft surface than perhaps any

other in Scotland. It is yet questionable whether these rocks are not older

than the similar Silurian deposits of Wales, the Isle of Man, and the north

of England.

All these great central

masses of what are called primitive rocks, were encased in an enormous

frame-work of the Deronian old red sandstone, and its associated

condlomerate; which maybe traced almost uninterruptedly along the whole

southern flank of the Grampians, and thence northwards, with very few

breaks, into the basin of the Moray Firth. With the exception of a small

number of protruding ridges and summits of granitic rocks, the whole shores

of this firth are composed of this old red sandstone; which, no doubt, at

one time, extended its layers across from side to side; and above and upon

which, from the few traces of them still remaining, deposits of has and

oolitic shales, grits, and limestones, appear to have rested. Perhaps these

were also surmounted by members of the chalk formation—rolled masses of

which have been discovered in Banff and Aberdeen shires; while in one or two

places, as at Elgin, singular local deposits of the era of the green sand

occur, with their peculiar and characteristic fossils. The amenity of the

climate, and fertility of the soil, round all the shores of the Moray Firth,

are owin4, in no small degree, to their being formed of members of the old

red sandstone series; which, in Caithness, extend themselves out in enormous

flat or undulating plains of bituminous and calcareous slates and

freestones; bestowing on that country, except along the sea-cliffs, a dead

and uninteresting outline. Almost all the bays and headlands along the north

coast, from the Pentland Firth westwards, are skirted or tipped with the

remains of the same Q cat old sandstone franc; which, as we round Cape

Wrath, soon meets us again pin enormous sheets an masses, composing mg the

greater of the coast as far south as Applecross, and rising, in the interior

of Sutherland, into huge detached peaks and pinnacles, apparently of red

horizontal masonry. The sandstones on this side of the island are

distinguished by their superior hardness and crystalline texture; and have

by some, especially in the neighbourhood of gneiss and mica slate, been

described as a sort of primitive sandstone.

The Hebrides are naturally divided into two groups: the outer, which

consists almost exclusively of gneiss rocks; and the inner, comprehending

Mull, Staffs, Eig, Rum, slid Skye, which, with their dependent islets,

consist of aoasis for the most part of secondary sandstones and limestone,

out of which have arisen, from the internal fiery nucleus of the earth,

enormous overlying, and, in some cases, overflowing masses and mountains of

trap rocks, chiefly greenstone, syenite, basalt, hyperatene, and an endless

variety of pitchstone, claystone, and felspar porphyries, with their

associated crystals and simple minerals. The precise localities of the most

interesting of all these deposits will he mentioned in our subsequent

chapters.

The Highlands and Islands of

Scotland exhibit in every direction the most unequivocal traces of all the

recent changes which have affected this portion of the globe. The principal

valleys and mountains appear to have received their present forms before the

British isles uprose from the deep; and everywhere the enormous quantities

of rolled stones or boulders, and of sand and gravel, not only betoken the

immense abrading forces to which the rocks were exposed, but those rounded

fragments, by their deposition in regular banks and terraces, also indicate

the successive heights at which the ocean, or sonic other great mass of

water, stood at long and different periods. Every valley and hill side

exhibit such appearances; and a series of corresponding terraces may be seen

extending to at least 1600 feet above the present sea level. The most marked

and general sea margin, however, is one which encircles the island with an

almost continuous ring, at an elevation of from 90 to 120 feet. This great

terraced bank is beautifully displayed on the seacoast in almost every part

of the Highlands, and in the cliffs above it, as at the Suture of Cromarty

and elsewhere, lutes of caverns may be seen marking other elevations at

which the sea had previously stood. The distinction observable in the Isle

of Man—and so fully described by the Rev. J. G. Cumming in his interesting

account of that island—between the boulder clay and the drift gravel of

these later deposits, may also he traced throughout the Highlands of

Scotland, and especially around Inverness, the former being the undermost,

but rising up front beneath the gravel banks to a higher elevation, and

often to the very tops of the hills. This boulder clay is the cause of the

superior fertility of some of our higher ridges, and in it are entombed by

far the largest of our erratic blocks. All the phenomena of scratching,

grooving, and polishing, so characteristic of what is called the Glacial

theory of the denudation and transport of rocks, are likewise abundantly

exemplified throughout the country. And lastly, the remains of the Irish

Elk, and of enormous trunks of Oak and Pine (with which no living examples

in this country can compare), imbedded in our peat mosses and quagmires,

both on the mainland and adjoining islands, betoken the extent and universal

diffusion of the ancient Caledonian forests, while the great size of those

remains excites a doubt whether a considerable change of climate has not

taken place since the era in which they existed. References will be given in

the body of this book to particular localities where all the phenoinena

alluded to may he distinctly seen.]

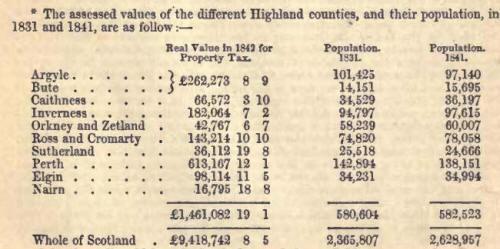

2. In speaking of Highland

hill property, as to extent, (excluding the lower and more fertile

portions,) miles may, without any great exaggeration, be substituted for

acres, to indicate a possession of a value corresponding with a Lowland

estate. In the assessment of real property in 1815, the annual ascertained

value of all the Highland counties, including Orkney and Zetland, with the

exception of Perth, Stirling, and Dumbarton shires, was £647,441; while the

real property of Fife and Dumfries shires, as assessed at the same time, was

£701,391. But the population of the Highland counties is double that of the

latter. The county of Perth was estimated at within £100,000 of all the rest

of the Highlands.*

3. The great mass of the

population of the Highlands is unquestionably of Celtic origin; those Celts

being (according to Mr. Skene, the latest essayist on this obscure point)

identical with the Picts, and the descendants of the ancient Caledonians of

Roman authors. With the Pictish inhabitants were afterwards incorporated the

Scots, of the same Celtic stock, who, from the north of Ireland, colonised

the south-west of Scotland, during the period between the third and the

sixth centuries. The Scots did not acquire a firm footing till the Romans

had abandoned Britain. They contended for the mastery with the Picts for

about 400 years, both nations merging into one in the ninth century. The

northern Picts, however, kept themselves greatly separate, and owned only a

nominal submission to the Scottish line of kings; and, retaining their

ancient territories and language, they were the real ancestors of the modern

Gael or Highlanders. The upper classes, however, were to some extent of

Scandinavian, more immediately of Norman origin, and, on the `vest coast, of

Danish or Norwegian lineage. In the reign of Malcolm III., or Ceanmore,

partly in consequence of his marriage with Margaret, sister of Atheling the

Saxon, Norman barons banished from his court began to effect settlements in

the Highlands. The Saxons are thought to have confined themselves to the

Lowlands. On the appearance of these strangers and their followers, feudal

policy came to be gradually blended with the old patriarchal or Celtic

system, which differed materially from feudalism. Society assumed the aspect

of a population divided into numerous communities, the members of each of

which had gradually amalgamated into a state of complete subordination of

all to one common head. We have presented, in the annals of the Highlands,

till within no very distant period, the spectacle of the most faithful

attachment on the part of inferiors to their superiors, though it partook of

a servile and dependent character. The sentiments of the upper ranks were

ordinarily marked by kindness and concern for the lower orders; but these,

again, were often vitiated by coarseness, and the proud selfishness

characteristic of an ignorant and barbarous age.

The separation of the tribes

or clans from one another by name and lineage, was rendered more complete

from the rugged nature of the country. In addition to a distinction of

surname and patronymics, the clans had each a different slogan or war-cry,

and a peculiar badge, generally some species of shrub, as the juniper, yew,

holly, &c., worn in the bonnet, and likewise a distinct variety of checkered

dress or tartan. They were remarkable for their jealousy of one another, and

of the association of men into towns, where society is held together by

principles and for purposes at variance with those of clanship. Constant

feuds and animosities, rapine, violence, and bloodshed, were the unavoidable

consequences of such a state of society. The warlike spirit of the

Highlanders was kept alive by the incursions, in more early periods, of the

Scandinavians, and by the abiding occasions of aggression on their own part

to spoil the rich possessions of their Saxon and other Lowland neighbours.

Hospitality there was, but of a barbaric and licentious character. The

domestic affections existed in great strength ; but there was little of

philanthropy or comprehensive sympathy with their fellow men. Indeed, the

kindlier feelings of our nature were, in Highlanders of the olden time,

unavoidably confined to a narrow range of objects, and the renovating

doctrines and principles of Christianity were most imperfectly understood

and practised. Considerable urbanity and politeness of demeanour prevailed

among the gentry ; but gross ignorance overspread the mass; and all the arts

of peace were at the lowest ebb. The chiefs resided in strongholds, each

generally a square tower of four or five single apartments, with perhaps

some adjoining buildings, and having at times a walled court. Their

household economy was distinguished by abundance—at least of animal food.

The residences of the ranks next in grade were mean, small, and comfortless

; while the peasantry, as is too universally the case at the present day,

were sheltered by dingy turf or dry stone huts, with bare earthen floors;

than which it is impossible to conceive abodes for human beings more squalid

and wretched. They were at the same time poorly fed ; but were, however,

uncommonly hardy and athletic. Their undaunted courage and energetic

strength, and their prowess in the use of their favourite weapons, the

claymore, dirk, and targe, rendered their very name a terror to the

industrious but more peaceful Lowlander.

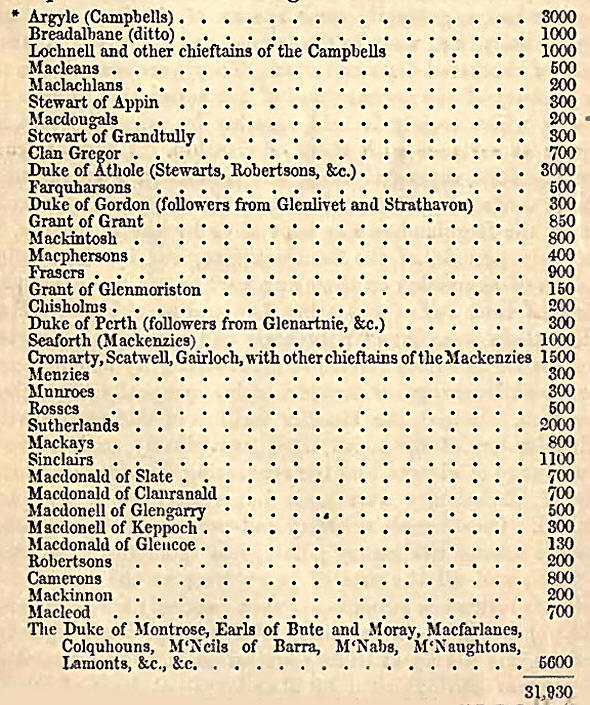

4. After the rebellion of

1745, a memorial was drawn up for government, it is conjectured by President

Forbes, which gives the subjoined estimate of the force of able-bodied men

which the respective clans could bring into the field.*

Several septs of other names

than those mentioned in this list were among the followers of some of the

more powerful chieftains. In point of dress, the kilt, a sort of plaited

petticoat, reaching to the knees, with the plaid, was universally worn by

the ordinary Highlander, while the lower garment of the upper ranks was the

trews, consisting of breeches and hose of one piece. The bagpipe was also

the common instrument of music.

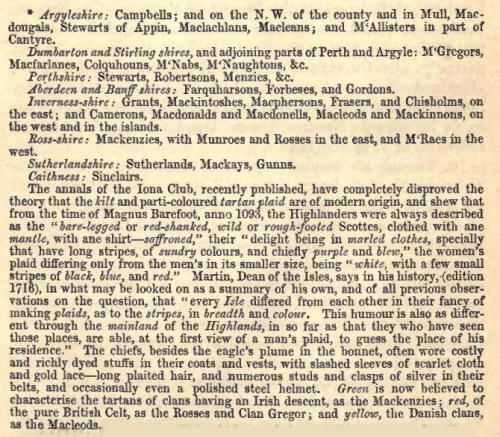

The distribution of the

various clans throughout the Highlands was, and still is, as underneath.*

5. The Western Isles were

long subject to the sway of Norway ; and though, on the discomfiture of

Haco's armament in the thirteenth century, they were transferred to the

dominion of the crown of Scotland, its sovereignty was for a long period not

recognised by the powerful kings or lords of the Isles, who maintained a

state of independent and supreme rule. Their strength was first materially

weakened by the subdivision of the family estates among the numerous sons of

the two families of John of Isla, by Amy, great-great-grand-daughter of

Reginald, King of Man, and Margaret, daughter of Robert II. of Scotland, and

the severely contested battle of Harlaw, fought by Donald of the Isles, in

1411, on occasion of an enterprise undertaken to make good his pretensions

to the earldom of Ross. This was followed by the overthrow of Alexander in

Lochaber, and by several determined measures of James I. and the succeeding

Scottish kings.

In general, the Scottish

kings observed the policy of sowing disunion and promoting feuds among the

clans; and James V. pursued, with partial success, vigorous measures to

bring them to some sort of obediential acknowledgment of the head of the

state; but the inaccessible nature of the country rendered the allegiance of

its rude inhabitants and stormy chieftains little more than nominal, as

regarded public police and good government. As if, however, to make amends

for their habitual disregard of any authority but their own will, the

Highlanders were prompt to rally round the standard of royalty when in

distress. The Argyleshire and Sutherland highlanders, however, form an

exception. They were always of Whig and presbyterian principles. To them

might be added the Rosses and Munroes. The Frasers, Mackintoshes, and

Grants, were also covenanting clans ; but the two former took part in the

later rebellions, the latter clan but partially. On the various occasions of

mutual co-operation, the Highland clans signalised themselves by

achievements of a truly remarkable character, considering their small

numerical strength; as, for instance, in Montrose's wars, Dundee's campaign,

and the rebellions of 1715 and 1745.

6. Though no decided

impression was made on their condition till the two latter risings, all

these seasons of combined effort were attended with some effect on the

manners and ideas of the various tribes. The soldiery stationed by Cromwell,

in the forts constructed by him, had also a considerable influence in

introducing some traits of refinement. At last the formation of the military

roads, and the disarming act in the period between the two rebellions, and

subsequent to that of 1745 the abolition of heritable jurisdictions,

ward-holdings, and of the Highland dress, and other coercive measures of

government, completely broke up the ancient system. A new field of adventure

was then unfolded to the young in civil and military professions in other

parts of the kingdom, and a spirit of independence was engendered quite

foreign to the former relations between the different classes of society.

Now, no peculiarities, springing from any essential distinction in the

constitution of the political and social body, exist between this and other

portions of the empire; none but such as must continue to mark the several

subdivisions of a country according to their elevation and the respective

degrees of commercial intercourse and wealth.

The progress of the Highlands

of Scotland towards an assimilation with the rest of the kingdom has, since

the middle of last, but more particularly since the commencement of the

present century, been singularly great, and its rapidity continually

accelerating. About the year 1730, several lines of roads were formed by the

Hanoverian soldiers, opening a communication along and from either

extremity, and also from the centre of the Great Glen with the south of

Scotland. In the year 1803, a parliamentary commission was appointed, under

whose sanction about £267,000 of the public money has been expended, of

which about £214,000 were advanced as the half of the expense of

constructing about 875 additional miles of roads and bridges throughout the

Highlands ; the heritors of the several counties assessing themselves to

defray the other half, (£214,000,) and £5000 a-year is allowed by government

towards the repair of roads. Numberless district roads intersect these,

formed by the statute-labour and local Road Acts, and other means. In the

county of Sutherland alone, there has been formed, since 1812, nearly 300

miles of road of this latter description, with assistance from the

Sutherland family, at an expense of about £40,000, affording three lines

from north to south, and another along the north coast, and the southern

boundary of the county.

7. The canals, roads, inns,

and modes of conveyance now existing in the Highlands, are described in the

body of this work, and it only remains for us to add, in this general

survey, that the residences of the better classes in the Highlands are now

provided with the usual comforts and conveniences of life; but the poorer

peasantry and labourers are often found immured, especially in the west

coast, in the most wretched huts, built chiefly of uncemented turf, with a

total disregard to neatness or cleanliness.

8. The chief export products

of the Highlands and Islands, are sheep, wool, black cattle, wood, kelp,

herrings, cod-fish, and salmon; and of late years, from the east of Ross and

Inverness, and from Caithness, wheat, oats, and potatoes. They are dependent

on other parts of the kingdom for groceries, and for most haberdashery,

hardware, and other manufactured goods. By the appropriation of certain

balances from the estates which were forfeited in the rebellions of last

century, about £i3,000 has been expended on harbours and piers; sums having

been advanced to individuals undertaking the completion of works to double

the amount received, making a total of £110,000 laid out on these objects by

this means. The exertions of the Highland Society of London, instituted in

1778, and that of Scotland, founded in Edinburgh in 1783, have been

eminently beneficial in fostering and quickening the capabilities of the

country. The objects of the former association are to preserve the language,

dress, music, and poetry of the Gael. Several societies in Scotland address

themselves to similar purposes, as the Celtic Society, the Highland Club of

Scotland, and the St. Fillan's Highland Society. The attention of the

Highland Society of Scotland is more immediately directed to the advancement

of Agricultural improvement in its various ramifications, by all the

appliances which such a great national institution can put in operation. And

its efforts have been attended by the most marked success.

9. The modern system of

sheep-farming on a great scale seems to have been too generally adopted,

with an inconsiderate degree of expedition, in some districts of the

Highlands. It is incompatible with the presence of a promiscuous population,

unconnected with the charge of the stock, and the consequence of its

introduction has accordingly been the dispossession of the inhabitants; and

that often on a sudden, without sufficient care being taken to open up to

them, on the coasts, or elsewhere, new sources of livelihood, and without

due respect to the propriety and expediency of dealing tenderly with their

local predilections and deeply-rooted habits. The rearing of cattle is not

so prejudiced by an intermixture of small crofters, or cottagers, and

requires a greater number of dependents. It is problematical whether the

rentals of Highland estates might not have benefited by a more limited

system of sheep-farming; while the condition of the tenantry in general, and

the peasantry, would have been improved thereby. It is difficult to form any

conjecture as to the total sheep stock, or yearly produce in sheep and wool,

of the whole of the Highlands. But from the statistical information procured

for a railway company projected in 1846, with the view of opening up the

communication with the southern markets, and developing the resources of the

north and central Highlands, it would appear that even in the present

backward state of things, there are annually exported by land from the

Highland counties (excluding the maritime shires of Banff, Aberdeen, and

Argyleshire, and the Lennox), about 200,000 head of sheep in a lean

condition, of which about 40,000 proceed from Perthshire alone, and the rest

from the northern shires; that Caithness, Sutherland, Ross, Inverness, and

part of Moray shires, send south about 40,000 head of lean cattle, and

Perthshire and the south Highlands about as many more; that from the

distance and difficulties of getting to market, the fattening of sheep and

cattle for the butcher has scarcely commenced in the Highlands; and that the

improvement of the stocks, by changes of breed from the south, is as yet,

from the same causes, very slow. Instead, therefore, of hill produce being

frequently and expeditiously disposed of, the Highland farmer can only get

rid of it once or twice a-year, and that in a lean condition, and at great

risk and expense. An annual great wool fair is held at Inverness in the

month of July, but though sometimes upwards of 100,000 stones of wool, and

as many sheep, change owners at it, the sales are often dull, and the grower

has to consign his stock to brokers in Glasgow and Liverpool. Great numbers

of sheep are still sent south on foot, across the hills, and the black

cattle follow them in large droves; and the animals so driven south

generally pass into English hands at the great trysts at Falkirk.

10. The Highland black cattle

are of a small size, but their beef is of a peculiarly delicate quality. For

the disposal of them, various trysts, or markets, are held throughout and on

the southern borders of the Highlands. Along with the droves of cattle,

parcels of Highland ponies are driven, which are of a small size, but strong

and hardy. Of these, a considerable number are destined for the north of

England coal mines. Both cattle and ponies are supplied in greatest numbers

by the west coast and islands. Highland ponies are capable of enduring great

fatigue. The larger breed of horses, when well cared for, form stout, hardy,

and serviceable animals. Crosses with south-country horses are now general

for agricultural purposes, draught, and riding.

11. Highland timber consists

chiefly of pine or fir, and birch. The former, when not of native growth, is

mostly disposed of in the shape of short props for the coal mines. About 200

or 300 cargoes of props, logs, and deals, are shipped annually from the

Moray Firth : the average value of a cargo of props does not exceed £30 or

£40. Coals and lime are brought back in return: birch is used for

herring-barrel staves, and for domestic utensils and farm implements. Oak

coppice is chiefly valuable for the charcoal and pyroligneous acid which it

yields; and larger stems of oak, ash, and elm, are now exported in

considerable quantities. There are, however, enormous plantations of fir and

larch shooting up in all parts of the country, and especially in the

interior, which cannot be turned to their full use until the communication

by railway is opened up. Thus, in the inland portions of Inverness and Nairn

shires alone (away from the sea), there are upwards of 50,000 acres under

wood; in Perthshire, on the line of the great north road, there are 26,000

acres of woodland; and the rest of the county must contain double that

quantity. The yearly exports of timber at present from the ports of the

Moray Firth alone, amount to about 50,000 tons.

12. There is generally,

manufactured about 8000 tons of kelp on the coasts of the western Highlands

and Islands ; from 2000 to 3000 tons in Orkney and Zetland; and probably

from 1000 to 1500 tons on the north and east coasts of Sutherland and

Caithness. During the last war, kelp often sold for £20 a ton ; but since

the introduction of Spanish barilla and other substitutes, it has fallen in

price from a half to a fourth of that sum. From a new alkaline product which

kelp has lately been found to contain, it is to be hoped that its value will

yet greatly rise. The expense of cutting, drying, and burning the ware is

from £3 to £4 a ton.

13. The seas of the north of

Scotland abound with valuable products; a fact which the industrious Dutch,

for a long period of time, turned to the most profitable account. Two

centuries ago, that people were in the habit of sending as many as 1500 and

even 2000 busses, of eighty tons each, to prosecute the herring fishery off

the coast of Shetland, besides several hundred doggers of about sixty tons'

burthen to fish for cod and ling. For the latter, also, they carried on an

extensive barter with the Shetland fishers. Towards the end of the

seventeenth century, the Dutch herring busses, from wars with this country,

and other causes, had decreased to 500 or 600, and they continued to

diminish still farther during the eighteenth century, and have now almost

disappeared from our coasts. Yet, seventy years ago, they had 200 busses

employed on the Shetland fishings; and the Danes, Prussians, French, and

Flemings, as many more; while the English had only two vessels, and the

Scotch but one. Public societies for the encouragement of the British

fisheries have been formed at various times in this country, since the reign

of Queen Elizabeth, previous to the society now established, but they were

short-lived, and their success was very partial. No attention was bestowed

on the herring fishery till the year 1750, when a company was incorporated,

which, however, eventually broke up, with a loss of £500,000 sterling. The

present British Fishery Society was established in 1780. Parliament has

frequently granted bounties for the encouragement of the fisheries; but as,

till of late, they were paid on the tonnage, and not on the quantity of fish

taken, vessels went out rather to catch the bounty than anything else. For

some years back, bounties for fishing herring have been found quite

unnecessary, and are now discontinued. Several fishing villages, as Tobermory, Ullapool, and Pulteney Town, near Wick, owe their origin to the

British Fishery Society.

On being forsaken by their

old friends the Dutch, the Shetland proprietors were obliged, in order to

enable their impoverished tenants to prosecute the ling fishery (to which

they had previously directed much of their attention), to advance the

purchase price of their boats and tackling, and, in return, the fishers

became bound to dispose of the produce of their labours to their landlords

at a stipulated price ; and this sort of tenure still prevails among these

islanders to this day. It was not till about thirty years ago that even a

feeble revival (by means of a few vessels of small burthen) was attempted of

the Shetland cod fishery, but since then it has been cultivated with great

success, and may yet be improved so as to become a source of much national

wealth ; for a prodigiously large cod, ling, and tusk bank has been

discovered, extending all the way from the north of Orkney to the west of

Shetland. There is every reason to believe that a similar bank lies to the

westward of the Hebrides; and the spirited gentry of those isles are

beginning to look after it.

14. The herring fishery was

at one time a source of great profit to the inhabitants of the west coast of

Scotland ; but it has of late somewhat fallen off in that direction, and

been prosecuted with most signal and daily increasing success on the eastern

shores. However, there are occasional great takes of herring in the

salt-water inlets on the west coast. In 1840, about £20,000 worth of herring

were cured in Loch Torridon; and, in 1841, as much as to the value of

perhaps £50,000 in Loch Duich. It is singular, that this economical article

of food is still so little used in the great manufacturing towns of England.

Of the quantity of salmon

cured, and the value of the fishery, we cannot speak with any certainty, as

the exports of this fish, though very considerable, vary much every year.

Including the Dee and the Don, there are, north of the Tay, twenty-five

salmon-fishing rivers of various importance, some of them yielding several

thousand pounds' rent. Besides which, the stake-net fisheries, along the

coasts of the firths and arms of the sea, return an additional revenue. This

branch of the fisheries has been greatly overwrought, and salmon in

consequence are much scarcer than they used to be: the subsisting law, which

makes the same close time (from the 14th September to the 2d of February) to

be observed all over Scotland, having also proved injurious, being opposed

to the habits of the fish in different rivers.

15. Besides these fish,

haddock, cod, whiting, skate, flounders, rock cod, and cuddies, abound in

most places. The haddock is rare on the west coast, (except towards the

south,) but its place is supplied by a fine firm fish, of somewhat similar

form, called the lythe. A new trade has lately commenced between the north

of Scotland and the London markets, in that most valuable of our white fish,

the haddock, which are now being picked up in vast quantities by steamers

and quick sailing vessels from the fishing boats, just as they are caught,

and brought to market either fresh or in a half cured state. The supply is

inexhaustible, and the demand in our great cities and manufacturing towns

for this fish is steadily increasing. When smoked and dried, the haddock is

becoming a staple article of food in many places, under the names, from

Aberdeen, of Finnan Haddies, or of Speldings, from other places. Turbot are

to be had in the Moray Firth, but unfortunately the fishermen have not

directed their attention to them. They are, however, industriously fished in

the Firth of Clyde. Soles are rarely to be seen in Scotland, as are also

mullet, gurnets, and the many varieties taken on the coasts of England.

Shell-fish naturally accompany the others enumerated. Crabs are common ;

lobsters are met with in many places; oysters are rare, except in some parts

of the west coast, whence they are occasionally brought to market in

Inverness and other towns, but by attention it is believed their numbers

might be greatly increased. Mussels (used chiefly for bait) abound on all

our coasts; and as care has lately been taken to preserve and increase the

spawn, the mussel banks belonging to our sea-ports and villages are becoming

sources of great revenue to them. Those of Inverness and Tain are already

worth to each about £100 a-year. Neither shrimps nor prawns fancy our

northern latitudes; but cockles occur in great quantities, and, where best,

form a highly palatable dish. Our mountain lakes, rivers, and streams,

afford, besides salmon, great varieties and abundance of trout. The char, or

mountain salmon, is found only occasionally, and in the higher lochs. Pike

of great size occur in many lakes ; but the presence of these voracious

animals is not desired, on account of their monopolising propensities.

16. Among the products of the

Highlands, game must not be omitted, being matter of very general interest,

and now no inconsiderable source of profit to many Highland proprietors.

Grouse, till of late, abounded in most parts of the Highlands, but now they

have been greatly reduced in number by sportsmen, by the treading of the

sheep and shepherd's dogs, and by various diseases, especially the

tape-worm. Partridges and hares are common in the low grounds: the ptarmigan

and mountain hare confine themselves to the rocky summits of the highest

mountains. Pheasants are being introduced in policies on the outskirts of

the Highlands and in the Hebrides. Black game or heath fowl abound in most

of the younger plantations and coppices, as also woodcocks ; and great

numbers of wild ducks, snipes, and other water-fowl, in the lakes and

marshes. The stately red deer keeps far remote from the haunts of man, but

they are still numerous in the more secluded wilds, and are now greatly on

the increase. Roe are frequent in the lower coverts. Deer-stalking requires

patience, and some hardiness of constitution. Hunting is out of the

question, and, indeed, coursing is hardly attempted; in the interior, and

most of the west coast, not at all. The deer-stalker must use the arts and

dexterity of the Indian in looking for his prey. The hare is pursued with

greyhounds, or the gun; while foxes, badgers, &c., must be unearthed by the

aid of the little wiry Scotch terrier. It has now become a common practice

for Highland proprietors to let the right of shooting on their grounds.

Moors may be had at all prices, from £30 to £700 for the season, with

accommodations varying according to circumstances. Mr. Snowie, gun-maker in

Inverness, is the chief agent in the north Highlands between the proprietors

of game and the sportsmen, and he regularly advertises the shootings which

are to let. His arrangements alone, extend over a rental amounting in some

years to between £7000 and £8000. His returns for seventy-six shootings,

three years ago, were 55,700 brace of grouse killed in the season, and 288

deer from twenty-six places where deer and roe occur. More precise and

extensive information is not to be got at present; but we know that, in the

estimates of railway traffic submitted to Parliament not long ago, there

were data procured for believing that the conveyance of game and small

parcels from the northern counties alone, would yield about £3500 a-year,

and of private carriages (chiefly used by sportsmen), horses, and dogs,

within a thousand pounds of the same sum.

17. Oat and barley meal, with

potatoes (until the partial failure of that root within the last three

years), form the staple articles of food of the mass of the population, to

which the peasantry add, when they can, a few herrings, and, on the coasts,

the other varieties of fish; but butcher's meat is a rarity they are seldom

able to afford. In the neighbourhood of towns, and even throughout the

country, the farmers willingly give .permission, to such as please to avail

themselves of it, to plant with potatoes as much land as they can supply

with manure; and thus many poor people, who are neither farm-servants, nor

possess crofts of their own, contrive to eke out a part of their

subsistence, by accumulating moss, fern, potato stems, sea ware, and

whatever else may serve as a component part of a dung-heap. In the towns and

villages, the bulk of the population earn their livelihood as artisans,

carters and day labourers; but, with a few trifling exceptions, there are no

manufacturing establishments. The distillation of smuggled spirits is now,

from the low price of whisky, and the efficiency of the excise, except in

remote districts, happily nearly abolished. It had a most demoralising

effect in those districts where it prevailed, giving rise to idleness,

duplicity, and dissipation. The crews of the revenue cutters, of whom about

two-thirds are constantly patroling the country under an officer of excise,

have, at a cost of only 58000 a-year, been the chief means of suppressing

smuggling. Many of the poor Highlanders earn a pound or two by annually

migrating in bands to the low country to assist in reaping the harvest; and,

when they can get employment as labourers on railways, they are eager to

avail themselves of it. In the herring-fishing season, thousands, who have

throughout the rest of the year no connexion with the sea, abandon their

usual occupations for a couple of months, and, as fishermen and fish-curers,

earn handsome though dear-bought wages. The clothing of the lower orders is

often wrought at home by themselves, and is ordinarily of a blue colour.

Plaiding and tartan are still a good deal worn; but the kilt is only

occasionally met with. Except in Caithness, where, as in Orkney and Zetland,

English is exclusively spoken, Gaelic is still the prevailing language in

the Highlands, particularly in the Hebrides, and the western and inland

parts of Argyle, Inverness, Ross, and Sutherland shires. The amended poor

law of 1845 has been put in force in all the parishes ; but notwithstanding,

poverty and wretchedness prevail to a most alarming extent. The landlords

cannot give full employment or subsistence; and hence government has been

appealed to, to afford funds necessary for transporting the population in

large numbers to the colonies. In the present state of agriculture and of

the fisheries, and the almost exclusive appropriation of the land to sheep,

any sensible relief by means of emigration alone, would be experienced only

by its being conducted on a very extensive scale indeed. Like the Irish, the

poor Highlander has been forced hitherto to seek his bread from home; and

the little education he gets to qualify him for doing so, he owes as much to

the exertions of benevolent societies and individuals in the south, as to

the institutions or liberality of the native proprietors and inhabitants.

Many impolitic and harsh clearances of the people have been carried through

within the last sixty years. The ignorance and want of skill in agriculture

in the peasantry, and their undue increase in certain localities after the

decline of the kelp trade, formed the chief pretext for such wholesale

removals; but the real causes, no doubt, were the inordinate expectations

formed by the proprietors of the profits of sheep farming, and their want of

capital to develop the resources of the country in the yield of grain and

timber, and the capabilities of the fisheries. The throwing together of the

poor people into crowded hamlets and villages, where it was attempted, in

some instances, to make artizans and manufacturers of them, and in others to

convert rustics into fishermen, with small patches of ground attached to

their dwellings, insufficient, when used even as potato plots, for the

support of their families, has also been a fruitful cause of destitution and

pauperism throughout the Highlands. But the clearances carried out on the

greatest scale were those in Sutherlandshire, which are more particularly

described in another part of this book. These have been the subject of

animadversion by numerous eminent authors, both foreign and domestic ; and

they are now generally regretted, and by none, we believe, more than by the

noble family in whose name they were effected. Ignorant of the habits,

attachments, and even language of the Celtic tribes, the advisers of those

measures hurried on improvements and arrangements which should have been

extended over many years, and been carried through with much patience and

tenderness towards a warm-hearted but easily excited people. Their pride and

indignation were roused, and they either expatriated themselves in large

bands, or like the imaginative Arab deprived of his liberty, became

broken-hearted and useless dependents.

18. These observations may

well be concluded by a glance at the ecclesiastical history, and a few

remarks on the state of education and religious instruction in the

Highlands.

The name of Christ was first

declared to the inhabitants of the Highlands by Columba (Gallicae St. Callum

or Malcolm), who came from Ireland, and settled in the island of Iona, about

the year 560. He sailed from the Emerald Isle along with a small band of

fellow missionaries (said to be twelve in number) in a little currach or

wicker boat; and although he subsequently visited the south of Scotland, his

labours were chiefly devoted to the conversion of the western and northern

Picts—as his predecessor St. Ninian in the fifth century, and St. Kentigern

or Mungo (founder of the see of Glasgow), and St. Patrick, a native of

Dumbarton, who were almost his contemporaries, laboured among the

Strathclyde Britons, and over the ancient kingdom of Cumbria, extending from

Loch Lomond to Windermere and Furness and the confines of Yorkshire; as well

as among the Celtic tribes of Wales and Ireland. The church in Scotland was

then unquestionably missionary or monastic, and did not become parochial or

territorial till David I.'s time; and like its Irish mother, it traced its

origin to the Eastern Church, not to that of Rome, whose first

representative, St. Austin or Augustine, only set foot in Kent in the year

597, two years after St. Columba's death. Educated in one of the small

monasteries instituted in the north of Ireland by St. Patrick, at a place

called Dearmach (from its being near an oak forest), the Scottish apostle

imbibed the simplicity and holy zeal of his preceptor; and when he and his

brother monks landed at Iona, we find, from his historian Adamnan, that they

retired for worship to a secluded circle of upright stones, previously, in

all likelihood, a Druidical temple, whence they afterwards issued "to gather

bundles of twigs to build their hospice." Their abodes were mere wigwams;

their churches, for long after, no better than log-houses of "hewn oak;" and

such was their humility, that they sought no better name than that of "Cuildhich"

(Culdees), signifying, according to the received opinion in Iona, "the

people that retire to corners," who worshipped God in dens and secret

recesses of the woods, but "in spirit and in truth." Hermits they might be

called, did they not, after being refreshed by meditation and prayer, go

forth to preach. Accordingly, St. Columba penetrated to the most remote

districts; and it is distinctly asserted by his contemporary biographers,

that he laboured at Inverness "ad ostiam Nessian" to convert Brudeus, king

of the northern Picts, at whose court also he held communications with a

Scandinavian earl of Orkney. Churches were subsequently dedicated to him in

all parts of the Highlands (as, for instance, Kilcalmakil, in the centre of

Sutherlandshire); and the Celtic brethren who accompanied or immediately

succeeded Columba, have their names recorded in very many of our parishes

and churches, the Gaelic origin of which are readily distinguishable from

the Saxon and Xorman names prevalent on the east and southern coasts of

Scotland, commemorative of Romish churchmen. Indeed, the exertions of

individual saints or hermits prior to Columba, who seems to have acted more

on a system of Episcopal arrangement, are now proved by undoubted records;

and St. Ninian at Whitherne in the fifth century, and St. Kieran, the

titular saint of Campbeltown in Argyleshire, and several others, laboured

singly among the Dalriadic Scots of that county early in the sixth century.

(See Mr. Howson's very valuable papers on the Ecclesiastical Antiquities of

Argyle, in the Cambridge Camden Society's Transactions, Parts II. and III.)

That these holy men retained much of apostolic Christianity, seems plain,

from the character left of them by old writers. "They never stirred abroad

but to gain souls. They preached more by example than word of mouth. The

simplicity of their garb, gesture, and behaviour, was irresistibly eloquent.

They did good to everybody, and sought no reward. Preferments, cabals,

intrigues, division, sedition, were things unknown to them. There were

bishops among them, but no lords; presbyters, but no stipends, or very small

ones; monks truly such—humble, retired, poor, chaste, sober, and zealous. In

a word, they were in a literal sense saints."—(Ibid, and Abercrombie's

'Mart. Ach. of Scotland, i., 106.) St. Columba and his disciples promoted

all the "arts of peace," especially medicine and agriculture ; and their

cures and recipes have been handed down to this day, in Gaelic legendary

rhymes constantly ascribed to them.

Among the Culdees the tonsure

was cut according to the Eastern fashion; and the great festival of Easter,

which regulates all the others, observed on the same day as in the East; but

in other respects the venerable Bede, and the Irish Annals, prove the Church

to have been completely Episcopal in its constitution, in the same sense as

it was so throughout the rest of Christendom. [See the subsequent account of

Iona.] It long struggled against the supremacy and corruptions of the Church

of Rome, which did not attain their full sway till the twelfth century, when

popish monachism was introduced: and even in the end of the thirteenth

century, some of the Culdees are found engaged in an unsuccessful opposition

to the new intruders. The regular creation of Sees in the Highlands, under

authority of the Crown, was, as follows, Mortlach (now Aberdeen), by Malcolm

III. in 1010: 'Moray and Caithness, including Sutherland, most probably by

the same prince. In the twelfth century, David I. founded, in addition to

the existing sees, that of Dunkeld, to which Argyle was at first annexed;

and he also constituted the bishopric of Ross. Alexander III., on the

acquisition of the Western Isles, added the ancient bishopric of Sodor, or

the Isles, to the national church. The Highlands and Islands were thus

partitioned into the seven dioceses of Dunkeld, Argyle, Moray, Ross, the

Isles, Caithness, and Orkney; the last being most likely a Norwegian see,

though Christianity was introduced to Orkney by St. Columba or his immediate

followers. It is difficult to form a conjecture as to the probable number of

the inferior clergy at this period, or the influence they and the doctrines

which they taught acquired over the rude and stormy inhabitants. Certain it

is, that a few faint rays of light continued to struggle against the

darkness of feudal strife and clannish jealousy; and the various religious

establishments sent forth among the people teachers animated with a desire

to lead them to a settled and peaceable mode of living ; while it is

likewise unquestionable, that many who, either from bodily infirmity or a

moral change of mind, found themselves unsuited to bear the coarse manners

of their countrymen, retired to the seclusion of the cloister for protection

and repose. The errors of popery, however, which had for a long time been

strenuously resisted in this kingdom, overspread and characterized the

church from the eleventh and twelfth centuries, even in the remote

Highlands. At the Reformation, the religious houses, as detailed in Keith's

Catalogue of the Scottish Bishops, were not numerous; and they belonged

chiefly to regular monks, who had not the spiritual charge of any particular

district, or any cure of souls. They were situated as follows:—The Canons

Regular had established houses at Loch Tay, on an island in that lake;

Rowadill, in the Isle of Harris; Crusay, in the Western Isles; in the

islands of Colonsay and Oronsay, and Insula St. Colmoci, and Inchmahome, in

the lake of Monteith; at Strathfallan, in Breadalbane, and Scarinche, in the

Isle of Lewis. The Red Friars had an establishment at Dornoch, in

Sutherland; the Preemonastratenses at Fearn, in Ross-shire; the

Cluniacenses at Icolmkill, in Iona; the Cistertians at Saddel, in

Cantyre; the monks of Valliscaullium at Beaulieu, or Beauly, at the head of

the Beauly Firth, and Ardchattan, on the side of Loch Etive, in Argyle: and

the Dominicans were domiciled at Inverness. There appears to have been but

one nunnery—at Icolmkill, in Iona; and one hospital—at Rothvan, in

Kiltarlity, Inverness-shire ; and only two collegiate churches for secular

canons, namely, Kilmun in Cowal, Argyle; and Tain, in Ross-shire, besides

the cathedral churches of Dunkeld, Lismore, Fortrose, Dornoch, and Kirkwall.

The diocesan church of Moray was the magnificent cathedral of Elgin, "the

lantern of the north"; and there were several abbeys and monasteries in that

county, as Kinloss and Pluscardine.

Patrick Hamilton, called the

first Scottish martyr for the doctrines of the Reformation, was an abbot of

Fearn, in Ross-shire; in which county and its neighbourhood, there is little

doubt, he advocated the truth in primitive power, gentleness, and

simplicity. Popery was finally abolished in 1560. Under the first

constitution of the reformed church (which was a medium between Episcopacy

and Presbyterianism, having superintendents to exercise Episcopal functions,

but without any Episcopal consecration), it was intended that the Highlands

should have had three of the ten superintendents appointed for the kingdom;

and be divided into three districts—Orkney, Ross, and Argyle. The latter

superintendency alone was filled up. On the remodelling of the form of

church government in 1572, when a more decided episcopacy was introduced,

the Highlands had five unconsecrated bishops, of the sees of Dunkeld, Moray,

Argyle, Caithness, and Orkney. Presbyterianism, after a severe struggle with

the power of the crown, was, for a time, fully established, in the year

1592. After various preparatory measures, bishops were restored to their

temporal estate in 1606; and Presbyterianism abolished, and Episcopacy

erected in its place in 1610. The bishops were regularly consecrated through

the English hierarchy; and we find the Highlands divided, as of old, into

the dioceses of Dunkeld, Argyle, Moray, Ross, the Isles, Caithness, and

Orkney. By the acts of Assembly 1638, and of the Scottish Parliament 1640,

Presbyterianism was reinstated, the bishops deposed, their order declared

unscriptural, and all the clergy put on a footing of equality. On the

Restoration, Episcopacy was again introduced, and ratified in 1662; and the

former bishops having died, a new consecration, by the hands of the English

bishops, took place, and the former sees in the Highlands were filled up.

The order of things was, owing to the political principles of the

Episcopalian clergy, once more reversed, and the Presbyterian form of

government finally settled in 1690; and it subsequently formed part of the

Articles of Union between the two kingdoms.

In the earlier years of the

reformed church, the preachers being few, and all the natural obstacles of

situation, poverty, and language, which, after the Revolution in 1688, long

retarded the efforts made to supply the Highlands with a ministry, existing

in full force, little generally effectual was done in the northern counties.

Even in 1650, some districts, as Lochaber, had had no Protestant ministry

planted in them. In others, however, some settlements were effected, very

early after the Reformation. Several clergy, of both reformed persuasions,

laboured in the north, in the beginning of the seventeenth century. In 1617,

a commission was appointed by parliament, for planting of kirks and

modifying stipends throughout Scotland; and to various succeeding

commissions additional powers were granted of dividing and remodelling

parishes; all which powers were, in 1707, transferred to the Court of

Session. Some settlements were made in the Highlands, and new presbyteries

erected during the Episcopal period between 1610 and 1638. The troubled

state of the country in the middle of the seventeenth century, was little

favourable to the enlargement of the church. In 1646, however, the General

Assembly of the Presbyterian Church, "in order that the knowledge of God in

Christ may be spread through the Highlands and Islands," enacted, "1. That

an order be procured, that all gentlemen who are able, do send their eldest

sons to be bred in the inland. 2. That a ministry be planted among them (the

Highlands;) and, for that effect, that ministers and exhortants, who can

speak the Irish language, be sent to employ their talents in these parts;

and kirks there be provided, as other kirks in this kingdom. 3. That Scots

schools be erected in all parishes there, according to the act of

parliament, where conveniently they can be had. 4. That all ministers and

ruling elders that have the Irish language, be appointed to visit these

parts."

The non-conforming clergy, or

such as refused to comply with the Episcopal establishment, and acknowledge

the order of bishops, were, in the Highlands as elsewhere, in many instances

ejected from their parishes, between the Restoration and Revolution.

Episcopacy, at this time, embraced the Confession of Faith promulgated by

the reformed church in 1567, the received standard of doctrine of both

denominations, prior to the drawing up of the Westminster Confession. After

the opposition offered to the attempted introduction, in 1637, of a liturgy

drawn up by the Scottish bishops and Archbishop Laud, along with the bishops

of London and Norwich, on the model of that of Edward VI., no general form

of prayer was appointed. The several bishops drew up, as before, each a

particular liturgy for his own flock, including a few petitions and collects

from the English Prayer-book; but even in the Presbyterian Church set forms

were observed, especially in the administration of the holy communion, down

to the year 1638, when the church, for the first time, authoritatively

assumed its most peculiar features of the entire parity of the clergy and

the exclusive use of extemporary prayer, with the disuse of the ancient

lessons from Scripture. As to church government, there were kirk-sessions,

presbyteries, and diocesan synods, but no national assemblies.

The Highlands must have been

in a very benighted state during the seventeenth century. Repeated

revolutions in church and state, a distracted state of society, and frequent

shifting of pastors, were ill calculated to foster dawning knowledge.

Detached districts only were supplied with spiritual guides; and of these

many understood indifferently, or not at all, the language of the people ;

while no Gaelic version of the Scriptures had been published, and there

subsisted an almost entire ignorance of even the art of reading. Popery

retained nearly exclusive dominion in the western section, and the isles of

Inverness and Ross. Episcopalian worship, in the Highlands, prevailed

chiefly about Dunkeld and Blair, and the town of Inverness; in Strathnairn

and Strathdearn; and also to some extent in Strathspey and Badenoch, and

more decidedly in the county of :Moray. It was also rooted in the south-east

of Ross-shire, and along the shores of the Linnhe Loch, in the vicinity of

Lismore. Such of the Episcopalian clergy, throughout the Highlands, as took

the oaths of allegiance to King William, which they did pretty generally,

were allowed to retain their livings; and, during the lives of these

incumbents, Episcopalian worship was accordingly maintained in their

parishes. The non jurors, who, from jaco bitical feelings, or conscientious

scruples, declined to take the oaths to government, were treated with no

little rigour, being legally interpelle from divine service in any place of

worship, and from administering baptism or marriage. The mild endurance of

the Episcopal Church has undoubtedly been the cause of its continuance to

this day.

The Church of Scotland, as by

law established, evinced considerable anxiety to supply the Highlands with

an adequate proportion of churches and clergymen. Successive acts of

Assembly were passed, by which bodies of ministers and probationers, or

expectants, were enjoined to visit and itinerate in the Highlands; and, to

defray their expenses, grants were obtained from the vacant stipends. The

settlement in any Lowland parishes of ministers having the Gaelic language

was forbidden, and settled clergymen understanding Gaelic were declared

transportable; so that, in the event of a call to a Highland parish, they

were bound to comply. Committees were appointed to visit Highland parishes,

with a view to the erection of churches and schools. By the year 1726, a

considerable effect was produced by these exertions. In 1724, the

Presbyteries of Loch Carron, Abertarff, and Skye, were erected, and, with

the Presbytery of Long Island, formed into a synod, called the Synod of

Glenelg. Orkney was, in the following year, divided into three presbyteries;

in 1726, the Presbytery of Tongue was established; and in 1729, those of

Mull and Lorn; and the Long Island was divided into two presbyteries in

1742. The attendant and corresponding progress of education will be

subsequently noticed.

19. In 1823, a sum of £50,000

was granted by government for building additional places of worship in the

Highlands and Islands of Scotland. With this sum thirty-two churches with

manses, one church without a manse, and ten manses,—where there were already

churches in which, for instance, the parish minister had been accustomed to

officiate occasionally,—have been built; about £10,000 extra having been

expended in general management. The services of forty-two ministers have

thus been secured, at an expense to the public of £120 to each, or £5040 per

annum. Small glebes and gardens are provided to the clergymen, who, with the

heritor making application for the church, are bound to keep church and

manse in repair, having the seat-rents consigned to them for that purpose.

The churches and manses, which have been constructed under the

superintendence of the Inspector of Highland roads and bridges, cost

respectively £720 and £750 each, and are of neat designs, and the churches

are capable of accommodating from 300 to 500 persons. These clergymen have

charge of a section of the several parishes under certain restrictions; and

they were admitted by the Assembly to be members of the Church courts in

June 1833.

20. The Episcopalian bishops

first consecrated by their ejected brethren, were not invested with the

charge of particular bounds, but the whole formed a college, having a

general concern in the affairs of their communion. This arrangement was

found inconvenient, and was changed in 1732, and the diocesan subdivision

reverted to, when three bishops were appointed for the Highlands; one to the

see of Dunkeld, another to that of Moray, Ross, and Argyle, and the third to

Orkney, Caithness, and the Isles. The rebellion of 1745 brought upon the

Episcopalians the most depressing enactments, which continued unrepealed

till 1792. No bishop has been required for Caithness and Orkney since 1762.

Moray, formerly joined with Ross and Argyle, is now restored to its

independent position; the see of Argyle and the Isles has again been

revived; and these, with Dunkeld, form the only present Highland dioceses.

The remnant of this persuasion, in the Highlands, are still found in nearly

the identical localities where Episcopacy at one time predominated; namely,

in Inverness, and the neighbouring district of Strathnairn, in the

south-east of Ross-shire, in Fort-William and Appin, and in the vicinity of

Dunkeld.

21. Until the disruption in

1842, dissent from the present establishment had made but little progress in

the Highlands. In Inverness-shire and the northern counties, it was confined

to the eastern coast, and the Orkneys and Zetland. The Church of Rome has

its congregations almost solely on the western coasts and islands of

Inverness-shire, along the course of the Caledonian Canal, and in the

diverging glens, in Inverness itself, and Strathglass adjoining, with a few

members in Badenoch. They are more numerous in Aberdeen and Banff shires,

and their clergy are most devoted to their flocks.

The most extraordinary

ecclesiastical change in Scotland of late years has been the disruption in

the Establishment in the year 1842. At that time the Presbyterian Church of

Scotland appeared to be impregnable in strength, and at no previous period

was it more efficient, or the clergy more zealous and exemplary. It enjoyed

an amount of civil liberty which the Church of Christ at no former time

seems to have had in the world, and although patronage, or the right of the

Crown or of lay patrons to present to livings, with some other minor

grievances, existed in name, practically the opinions, and even feelings of

the people, in the settlements of the clergy, were almost universally

consulted and acquiesced in. The power of public opinion (if that be of any

value in religion) was becoming more operative, and the popular party in the

church courts had attained a preponderating influence. State endowments had

not corrupted the ministers, but on the contrary had aided them in their

studies, and helped them not only to contribute liberally to every good work

at home and abroad, but had enabled them to preach the gospel in all its

fulness and freeness, uninfluenced by the local prejudices or contracted

views of their sessions and people, which operate so strongly among the

other sects. The clergy were almost uncontrolled in their power; certain of

the most eminent of them had evidently in effect, though not in name,

overstepped the notion of Presbyterian parity; and in the church courts an

agitation was commenced, fomented by popular clamour from without, and

unrestrained by the presence of a sufficient number of men of deliberate

business habits within, which of a sudden demanded a total independence of

the civil courts, and an unreserved concession by the legislature of the

most democratic features of Presbyterian Church government. Litigations

ensued about the presentation and deposition of ministers before the civil

tribunals, without a previous appreciation of the extent to which the

judicial findings would or would not be submitted to. The decrees of the

highest courts when adverse were repudiated, and the most threatening

language resorted to. The government assumed an equally high position, and

was but ill informed of the lengths to which the people would go, and of the

solemn engagements by which the clergy were confederated together not to

yield an iota of their claims. Hence a disruption which in one day emptied

500 pulpits in Scotland, divided the people into two nearly equal parts, and

which in the Highlands and Islands caused at least three fourths of them to

"go out" from the establishment with the pastors by whom they were led, and

to whom they were most justly and warmly attached. Although the most

extraordinary exertions and sacrifices have been made by the seceding party,

under the name of the Free Church of Scotland, to maintain their principles

and support their clergy by voluntary contributions, it is evident that the

struggle in the Highlands has been most unequal and lamentable. There the

people cannot afford to support the church; they must depend on their

friends in the south for aid, and this will not be given always. Already

some of their best preachers are being called away to better livings—the

Gaelic population in the southern towns is draining the north of her best

students ; and the establishment, which has much difficulty in supplying

vacant charges, especially with ministers who speak Gaelic, labours under

the disadvantage of being proclaimed as no church at all (or at best "as a

body without a soul!") by the very parties who use the same forms of worship

as itself, and profess identically the same Confession of Faith ! Meanwhile

the people are losing their reverence for ordinances as such, from a

disposition to receive them at the hands only of certain individuals, and as

discipline though attempted to be strictly enforced is easily evaded. The

several evil consequences to be apprehended, and to some extent developed,

are now happily being counteracted, as, fortunately, although much acrimony

of feeling prevailed for sometime after the disruption, the good sense of

the people is now leading them to act as citizens in harmony. For the stand

made by the Free Church for spiritual independence, they are entitled to

much respect; but their charge against the Establishment and State that they

have disowned the Great Head of the Church, is a slander discreditable to

its abettors, and indignantly repudiated by the adherents of the

Establishment, and universally condemned by all unbiassed persons. In

preaching, the high and most austere Calvinism of the Puritan times is

promulgated and encouraged in the Free Church, from which the Established

clergy have been gradually receding, and losing with such recession somewhat

of their popularity.

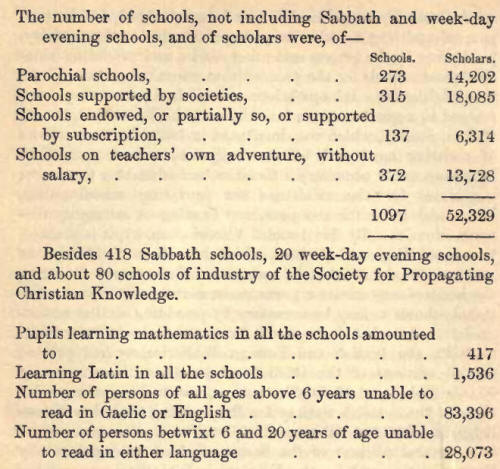

22. We shall now review

shortly the progress of education, and the establishment of schools in the

Highlands. The early solicitude which existed in Scotland on the subject of

education is gratifying and interesting. Thus, in the reign of James IV.,

(1496) an act of Parliament was passed, ordaining that all "baronis and

substantious freeholders sould put their airs to ye schulis." The project of

the system of parochial schools, which may justly be deemed the basis of

education in this country, was first entertained by the Privy Council in

1616. Their act proceeds on the narrative of being for the promotion of "ci

vilitie, godliness, knowledge, and learning;" and that the youth of the

kingdom might be taught "at the least to write and read, and be catechised

and instructed in the grounds of religion." Religion was thus made the