|

Fresh-Water Fish not of much value - The Angler and his Equipment -

Pleasures of the Country in May - Anglers' Fishes - Trout, Pike, Perch,

and Carp - Gipsy Anglers - Angling Localities - Gold Fish - The River

Scenery of England - The Thames - Thames Anglers - Sea Angling - Various

Kinds of Sea-Fish - Proper Kinds of Bait - The Tackle necessary - The

Island of Arran - Corry - Goatfell, etc.

ALTHOUGH it may be deemed

necessary in a work like the present to devote some space to the subject,

I do not set much store by the common anglers' fishes, so far, at least,

as their food value is concerned ; for although we were to cultivate them

to their highest pitch, and by means of artificial spawning multiply them

exceedingly, they would never (the salmon, of course, excepted) form an

article of any great commercial value in this beef-eating country. In

France, where the Church enjoins many fasts and strict sumptuary laws, the

people require, in the inland districts especially, to have recourse to

the meanest produce of the rivers in order to carry out the injunctions of

their priests. The smallest streams are therefore assiduously cultivated

in many continental countries ; but the fresh-water fishes of the British

Islands have only at present a very slight commercial value, as they are

not captured, either individually or in the aggregate, for the purposes of

commerce ; but to persons fond of angling they afford sport and healthful

recreation, whether they are pursued in the large English or Scottish

lakes, or caught in the small rivulets that feed our great salmon streams.

Although Britain is possessed of a seabord of 4000 miles, and a large

number of fine rivers and lakes, the total number of British fishes is

comparatively small (about 250 only), and the varieties which live in the

fresh water are therefore very limited ; those that afford snort may be

numbered with ease on our ten fingers. Fishers who live in the vicinity of

large cities are obliged in consequence to content themselves with the

realisation of that old proverb which tells them that small fish are

better than no fish at all ; hence there is a race of anglers who are

contented to sit all day in a punt on the Thames, happy when evening

arrives to find their patience rewarded with a fisher's dozen of stupid

gudgeons. But in the north, on the lakes of Cumberland or on the Highland

lochs of Scotland, such tame sport would be laughed at. Are there not

charr in the Derwent and splendid trout in Loch Awe I and these require to

be pursued with a zeal, and involve an amount of labour, not understood by

anglers who punt for gudgeon or who haunt the East India Docks for perch,

or the angler who only knows the usual run of Thames fish-barbel, roach,

dace, and gudgeon. To kill a sixteen-pound salmon on a Welsh or Highland

stream is to be named a knight among anglers ; indeed, there are men who

never lift a rod except to kill a salmon ; such, however, like the Duke of

Roxburghe, are giants among their fellows. For sport there is no fish like

the "monarch of the brook," and great anglers will not waste time on any

fish less noble. An angler, with a moderate-sized fish of the salmon kind

at the end of his line, is not in the enjoyment of a sinecure, although he

would not for any kind of reward allow his work to be done by deputy. I

have seen a gentleman play a fish for four hours rather than yield his rod

to the attendant gillie, who could have landed the fish in half-an-hour's

time. It is a thrilling moment to find that, for the first time, one has

hooked a salmon, and the event produces a nervousness that certainly does

not tend to the speedy landing of the fish. The first idea, naturally

enough, is to haul our scaly friend out of the water by sheer force ; but

this plan has speedily to be abandoned, for the fish, making an astonished

dash, rushes away up stream in fine style, taking out no end of "rope;"

then when once it obtains a bite of its bridle away it goes sulking into

some rocky hiding-place. In a brief time it comes out again with renewed

vigour, determined as it would seem to try your mettle ; and so it dashes

about till you become so fatigued as not to care whether you land it or

not. It is impossible to say how long an angler may have to "play" a

salmon or a large grilse ; but if it sinks itself to the bottom of a deep

pool, it may be a business of hours to get it safe into the landing net,

if the fish be not altogether lost, as in its exertions to escape it may

so chafe the line as to cause it to snap, and thus regain its liberty ;

and during the progress of the battle the angler has certainly to wade, ay

and be pulled once or twice through the stream, so that he comes in for a

thorough drenching, and may, as many have to do, go home after a hard

day's work without being rewarded by the capture of a single fish.

There is abundance of good salmon-angling to be had at the proper season

in the north of Scotland, where there are always a great variety of

fishings to let at prices suitable for all pockets; and there is nothing

better either for health or recreation than a day on a salmon stream.

There are one or two places on Tweed frequented by anglers who take a

fishing as a sort of joint-stock company, and who, when they are not

angling, talk politics, make poetry, bandy about their polite chaff, and

generally " go in," as they say, for any amount of amusement. These

societies are of course very select, and not easily accessible to

strangers, being of the nature of a club. The plan which every angler

ought to adopt on going to a strange water is to place himself under the

guidance of some shrewd native of the place, who will show him all the

best pools and aid him with his advice as to what flies he ought to use,

and give him many useful hints on other points as well. Anglers, however,

must divide their attention, for it is quite as interesting (not to speak

of convenience) for some men to spend a day on the Thames killing barbel

or roach as it is to others to kill a ten-pound salmon on the Tweed or the

Spey. It is good sport also to troll for pike in the Lodden or to capture

grayling in beautiful Dovedale. And so pleasant has of late years become

the sport, that it is now quite a common sight to see a gentle-born lady

handling a salmon-rod with much vigour on some of our picturesque Highland

or border streams. In fact, angling is a recreation that can be made to

suit all classes, from the child with his stick and crooked pin to the

gentleman with his well-mounted rod and elaborate tackle, who hies away in

his yacht to the fiords of Norway in search of salmon that weigh from

twenty to forty pounds, and require half a day to capture. For those,

however, who desire to stay at home there is abundant angling all the year

round. From NewYear's Day to Christmas there needs be no stoppage of the

sport ; even the weather should never stop an enthusiastic angler ; but on

very bad days, when it is not possible to go put of doors, there is the

study of the fish, and their natural and economic history, which ought to

be interesting to all who use the angle, and to the majority of mankind

besides.

Without pretending to rival the hundred and one guides to angling that now

flood the market, I shall take a glance at a few of the more popular of

the angler's fishes ; not, however, in any scientific or other order of

precedence, but beginning with the trout, seeing that the salmon is

discussed in a separate division of this work.

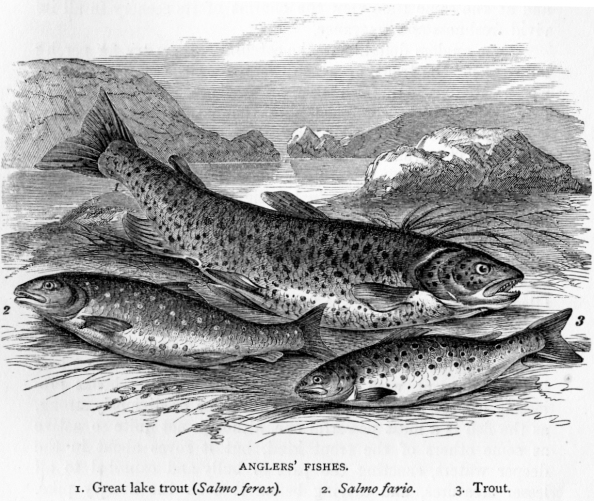

Of all our fresh-water fishes, the one that is most plentiful, and the one

that is most worthy of notice by anglers, is the trout. It can be fished

for with the simplest possible kind of rod in the most tiny stream, or be

captured by elaborate apparatus on the great lochs of Scotland. There are

so many varieties of it as to suit all tastes ; there are well-flavoured

burn trout, not so large as a small herring, and there are lake giants

that, when placed in the scales, will pull down a twenty-pound weight. The

usual run of river trout, however, is about six or eight ounces in weight

; a pound trout is an excellent reward for the patient angler. Where a

fronting stream flows through a rich and fertile district of country, with

abundant drainage, the trout are usually well-conditioned and large, and

of good flavour ; but when the country through which the stream flows is

poor and rocky, with no drains carrying in food to enrich the stream, the

fish are, as a matter of course, lanky and flavourless ; they may be

numerous, but they will be of small size. It is curious, too, to note the

difference of the fish of the same stream : some of the trout taken in

Tweed, and in other rivers as well, are sharp in their colour, have fine

fat plump thick shoulders, great depth of belly, and beautiful pink flesh

of excellent flavour. The flavour of trout is of course dependent on the

quality and abundance of its food ; those are best which exist on

ground-feeding, living upon worms and such fresh-water crustaceans as are

within reach. Fly-taking fish-those that indulge in the feed of ephemerae

that takes place a few times every day-are comparatively poor in flesh and

weak in flavour. As to where fishers should resort, must be left to

themselves. I was once beguiled out to the Dipple, but it is a hungry sort

of river, where the trout were on the average only about three ounces, and

scarce enough ; although I must say that for a few minutes, when "the

feed" was on the water, there was an enormous display of fish, but they

preferred to remain in their native stream, a tributary of the Clyde I

think. The mountain streams and lochs of Scotland, or the placid and

picturesque lakes of Cumberland and Westmoreland, are the paradise of

anglers.

For trout-fishing I would name Scotland as being before all other

countries. "What," it has been asked, " is a Scottish stream without its

trout ? " Doubtless, if a river has no trout it is without one of its

greatest charms, and it is pleasant to record that, except in the

neighbourhood of very large seats of population, trout are still plentiful

in Scotland. It is true the railway, and other modes of conveyance, have

carried of late years a perfect army of anglers into its most picturesque

nooks and corners, and therefore fish are not so plentiful as they were

fifty years since, in the old coaching days, when it was possible to fill

a washing-tub in the space of half-an-hour with lovely half-pound trout

from a few pools on a burn near Moffat. But there are still plenty of

trout ; indeed there are noted Scotch fishers who can fill baskets from

streams near large cities that have been too much fished.

The place to try an angler is a fine Border stream or a grand Highland

loch ; but I shall not presume to lay down minute directions as to how to

angle, for an angler, like a poet, must be born, he can scarcely be bred,

and no amount of book lore can confer upon a man the magic power of luring

the wary trout from its crystalline home. The best anglers, and

fish-poachers, are gipsies. A gipsy will raise fish when no other human

being can move them. If encamped near a stream, a gipsy baud are sure to

have fish as a portion of their daily food ; and how beautifully they can

broil a trout or boil a grilse those only who have dined with them can

say. Your gipsy is a rare good fisher, and with half a rod can rob a river

of a few dozens of trout in a very brief space of time, and he can do so

while men with elaborate "fishing machines," fitted up with costly tackle,

continue to flog the water without obtaining more than a questionable

nibble, just as if the fish knew that they were greenhorns, and took

pleasure in chaffing them. Mr. Cheek, who wrote a capital book for the

guidance of those I may call Thames anglers, says that the best way to

learn is to see other anglers at work-which is better than all the written

instructions that can be given, one hour's practical information going

farther than a folio volume of written-advice. It is all in vain for men

to fancy that a suit of new Tweeds, a fair acquaintance with Stoddart or

Stewart, and a large amount of angling "slang," will make them fishers.

There is more than that required. Besides the natural taste, there is

wanted a large measure of patience and skill ; and the proper place to

acquire these best virtues of the angler is among the brawling hill

streams of Scotland, or on the expansive bosom of some Cumberland lake,

while trying for a few delicious charr. A congregation of fish brought

together by means of a scatter of food and an angler's taking advantage of

the piscine convention over its diet of worms, is no more angling than a

battue is sport. An American that I have heard of has a fish-manufactory

in Connecticut, where he can shovel the animals out by the hundred ; but

then he does not go in for sport; his idea-a thoroughly American one-is

money ! But despite this exceedingly commercial idea, there are a few

anglers in America, and as water and game fishes abound, there is plenty

of sport. In North America are to be found both the true salmon and the

brook trout ; and as a great number of the American fishes visit the fresh

and salt water alternately, they, by reason of their strength and size,

afford excellent employment either to the river or sea angler. One of the

best American fishes is called the Mackinaw salmon.

To come back, in the meantime, to Scotland and the trout, and where to

find them, I may mention that that particular fish is the stock in trade

of the streams and lochs of Scotland, - Scotland, the "land of the

mountain and the flood," - and there is an ever-abiding abundance of

water, for the lochs and streams of that country are numberless. One

county alone (Sutherland, to wit) contains a thousand lochs, and one

parish in that county has in it two hundred sheets of water, all abounding

with fine trout, affording sport to the angler-rewarding all who persevere

with full baskets. As I have already hinted, the fisher must study his

locality and glean advice from well-informed residents. The gipsies of a

district can usually give capital advice as to the kind of bait that will

please best. Many a time have anglers been seen flogging away at a stream

or lake that was troutless, or at their wit's end as to which of their

flies would please the dainty palate of my lord the resident trout. But I

shall not further dogmatise on such matters ; most people given to angling

are quite as wise, on that subject at least, as the writer of these

remarks ; and there are as fine trout in England, I daresay, as there are

in Scotland ; indeed there are a thousand streams in Great Britain and

Ireland where we can find fish - there are splendid trout even in the

Thames. Then there are the Dove and the Severn, as well as rivers that are

much farther away, so that on his second day from London an active angler

may be whipping the Spey for salmon, or trolling on Loch Awe for the large

trout that inhabit that sheet of water. The change of scene is of itself a

delight, no matter what river the visitor may choose. At the same time the

physical exertion undergone by the angler flushes his cheek with the hue

of health,

and imparts to his frame a

strength and elasticity known only to such as are familiar with country

scenes and pure air. May and the Mayfly are held to inaugurate the

angler's year; for although a few of the keenest sportsmen keep on angling

all the year round, most of them lay down their rod about the end of

October, and do not think of again resuming it till they can smell the

sweet fragrance of the advancing summer. Although few of our busy men of

law or commerce are able to forestall the regular holiday period of August

and September, yet a few do manage a run to the country at the charming

time of May, when the days are not too hot for enjoyment nor too short for

country industry. In August and September the landscape is preparing for

the sleep of winter, whilst in May it is being

robed by nature for the fetes of summer, and, despite

the sneers of some poets and naturalists, is new and charming in the

highest degree. Town living people should visit the country in May, and

see and feel its industry, pastoral and simple as it is, and at the

same time view the charms of its scenery in all its vivid freshness and

fragrance.

Some anglers delight in

pike-catching, others try for perch ; but give me the trout, of which

there is a large variety, and all worth catching. In Loch Awe, for

instance, there is the great lake trout, which, combined with the beauty

of the scenery, has sufficed to draw to that neighbourhood some of our

best anglers. The trout of Loch Awe, as is well known, are very ferocious,

hence their scientific name of

Salmo ferox.

It attains to great dimensions ; individuals

weighing twenty pounds have been often captured ; but its flavour is

indifferent and the flesh is coarse, and not prepossessing in colour. This

kind of trout is found in nearly all the large and deep lochs of Scotland.

It was discovered scientifically about the end of last century by a

Glasgow merchant, who was fond of sending samples of it to his friends in

proof of his prowess as an angler. The usual way of taking the great lake

trout is to engage a boat to fish from, which must be rowed gently through

the water. The best bait is a small trout, with at least half-a-dozen

strong hooks projecting from it, and the tackle requires to be

prodigiously strong, as the fish is a most powerful one, although not

quite so active as some others of the trout kind, but it roves about in

the deeper waters, enacting the part of bully and cannibal to all lesser

creatures, and driving before it even the hungry pike. Persons residing

near the great lochs capture these large trout by setting night lines for

them. As has been already mentioned, they are exceedingly voracious, and

have been known to be dragged for long distances, and even after losing

hold of the bait to seize it again with much eagerness, and so have been

finally captured. These great lake trout are also to be found in other

countries.

In Lochleven, at Kinross,

twenty-two miles from Edinburgh, there will be found localised that

beautiful trout which is peculiar to this one loch, and which I have

already referred to as one of the mysterious fishes of Scotland. This fish

-although its quality is said to have been degenerated by the drainage of

the lake in 1830, at which period it was reduced by draining to a third of

its former dimensions-is of considerable commercial value ; it cannot be

bought in Edinburgh or London except at a fancy price ; and if it was

properly cultivated might yield a large revenue. I have not been able to

obtain recent statistics of " the take " of Lochleven trout, but in former

years, during the seven months of the fishing season, it used to range

from fifteen thousand to twenty thousand pounds weight, and at the time

referred to all trout under three-quarters of a pound in weight were

thrown back into the water by order of the lessee. Eighty-five dozen of

these fine trout have been known to be taken at a single haul, while from

twenty to thirty dozen used to be a very common take. As to perch, they

used to be caught in thousands. Little has or can be said about Lochleven

trout, except that they are a specialty. Some learned people (but I take

leave to differ from them) consider the Lochleven fish to be identical

with Salmo fario, but never in any of my piscatorial wanderings

have I found its equal in colour, flavour, or shape. It has been compared

with the Fario Lemanus of the Lake of Geneva, and having handled

both fishes, I must allow that there is very little difference between

them ; but still there are differences. Netting is not now allowed on the

loch, but there is a large fleet of boats, which can be hired at Kinross

for an hour or two's fishing on Lochleven.

I need not go over all the

varieties of fresh-water trout seriatim, for their name is legion,

and every book on angling contains lists of those peculiar to districts.

If anglers' fishes ever become valuable as food, it will be by the

cultivation of our great lochs. With such a vast expanse of water as is

contained in some of these lakes, and having ample river accommodation at

hand for spawning purposes, there could be no doubt that artificial

breeding, if properly gone about, would be successful. The Lochleven trout

is already of great money value commercially, and could be systematically

cultivated so as to become a considerable source of revenue to the

proprietor of the lake and amusement to the angler ; an experimental

attempt at cultivation took place some years ago, but no regular plan of

breeding these fish has yet been organised.

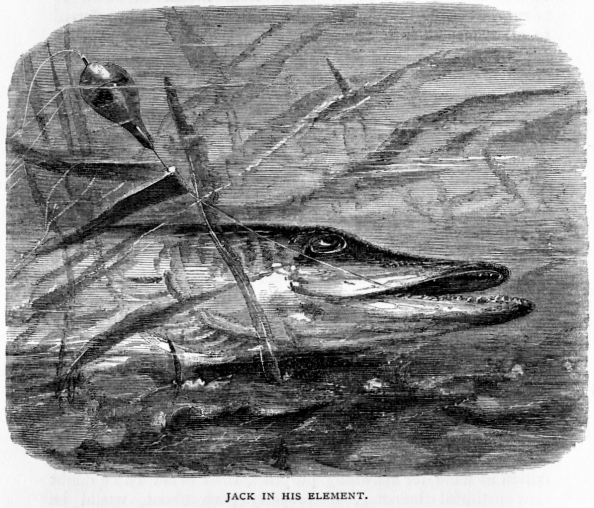

There are some pretty big

pike in Lochleven. As every angler knows, the pike affords capital sport,

and may be taken in many different ways. Pike spawn in March and April,

when the fish leaves its hiding-place in the deep water and retires for

procreative purposes into shallow creeks or ditches. The pike

yields a very large quantity of roe on

the average, and the young fish are not long in being hatched. Endowed

with great feeding power, pike grow rapidly from the first, attaining a

length of twenty-two inches. Before that period a young pike is called a

jack, and its increase of weight is at the rate of about four

pounds a year when well supplied

with food. The appetite of this fish is very great, and, from its being so

fierce, it has been called the pirate of the rivers. It is not easily

satisfied with food, and numerous extraordinary stories of the pike's

powers of eating and digesting have been from time to time related. I

remember, when at school at Haddington (seventeen miles from Edinburgh),

of seeing a pike that inhabited a hole in the "Lang Cram" (a part of the

river Tyne), which was nearly triangular in shape, supposed to be the

exact pattern of its hiding-place, and which devoured every kind of fish

or animal that came in its way. It was hooked several times, but always

managed to escape, and must have weighed at least twenty-five pounds. Upon

one occasion it was hooked by a little boy, who fished for it with a

mouse, when it rewarded him for his cleverness by dragging him into the

water ; and had help not been at hand the boy would assuredly have been

drowned, as the water at that particular spot was deep. As to the voracity

of this fish many particulars have been given. Mr. Jesse, in one of his

works, says that a pike of the weight of five pounds has been known to eat

a hundred gudgeon in three weeks ; and I have myself seen them killed in

the neighbourhood of a shoal of parr, and, notwithstanding their rapidity

of digestion, I have seen four or five fish taken out of the stomach of

each. Mr. Stoddart, one of our chief angling authorities, has calculated

the pike to be amongst the most deadly enemies of the infant salmon. He

tells us that the pike of the Teviot, a tributary of the Tweed, are very

fond of eating young smolts, and says that, in a stretch of water ten

miles long, where there is good feeding, there will be at least a thousand

pike, and that these during a period of sixty days will consume about a

quarter of a million of young salmon !

One would almost suppose that some

of the stories about the voracity of pike had been invented ; if only half

of them be true, this fish has certainly well earned its title of shark of

the fresh water. There is, for instance, the well-known tale of the poor

mule, which a pike was seen to take by the nose and pull into the water ;

but it is more likely I think that the mule pulled out the pike. Pennant,

however, relates a story of a pike that is known to be true. On the Duke

of Sutherland's Canal at Trentham, a pike seized the head of a swan that

was feeding under water, and gorged as much of it as killed both. A

servant, perceiving the swan with its head below the surface for a longer

time than usual, went to see what was wrong, and found both swan and pike

dead. A large pike, if it has the chance,

will think nothing of biting its captor ;

there are several authentic instances of this having been done. The pike

is a long-lived fish, grows to a large size, and attains a prodigious

weight. There is a narrative extant about one that was said to be two

centuries and a half old, which weighed three hundred and fifty pounds,

and was seventeen feet long. There is abundant evidence of the size of

pike : individuals have been captured in Scotland, so we are told in the

Scots Magazine, that weighed seventy-nine pounds. In the London newspapers

of 1765 an account is given of the draining of a pool, twenty-seven feet

deep, at the Lilishall Limeworks, near Newport, which had not been fished

for many years, and from which a gigantic pike was taken that weighed one

hundred and seventy pounds, being heavier than a man of twelve stone ! I

have seen scores of pike which weighed upwards of half a stone, and a good

many double that weight, but the weight is thought now to be on the

descending ratio, the giants of the tribe having been apparently all

captured. Formerly there used to be great hauls of this fish taken out of

the water. Whether or not a pike be good for food depends greatly on where

it has been fed, what it has eaten, and how it has been cooked. In fact,

as I have already endeavoured to show, the animals of the water are in

respect of food not unlike those of the land-their flavour is largely

dependent on their feeding ; and pike that have been luxuriating on

Lochleven trout, or feeding daintily for a few months on young salmon,

cannot be very bad fare.

The carp family (Cyprinidae) is very numerous,

embracing among its members the barbel, the gudgeon, the carp-bream, the

white-bream, the red-eye, the roach, the bleak, the dace, and the

well-known minnow. There is one of the family which is of a beautiful

colour, and with which all are familiar-I mean the golden carp, which may

be seen floating in its crystal prison in nearly every home of taste, and

which swarms in the ponds at Hampton Court, in the tropical waters of the

Crystal Palace at Sydenham, as also in all the great aquariums. The gold

and silver fish are natives of China, whence they were introduced into

this country by the Portuguese about the end of the seventeenth century,

and have become, especially of late years, so common as to be hawked about

the streets for sale. In China, as we can read, every person of fashion

keeps gold-fish by way of having a little amusement. They are contained

either in the small basins that decorate the courts of the Chinese houses,

or in porcelain vases made on purpose ; and the most beautiful kinds are

taken from a small mountain lake in the province of Che-Kyang, where they

grow to a comparatively large size, some attaining a length of eighteen

inches and a comparative bulk, the general run of them being equal in size

to our herrings. These lovely fish afford much delight to the Chinese

ladies, who tend and cultivate them with great care. They keep them in

very large basins, and a common earthen pan is generally placed

at the bottom of these in a reversed position, and so

perforated with holes as to afford shelter to the fish from the heat and

glare of the sun. Green stuff of some kind is also thrown upon the water

to keep it cool, and it (the water) must be partially changed every two

days, and the fish, as a general rule, must never be touched by the hand.

Great quantities of gold-fish are often bred in ponds adjacent to

factories, where the waste steam being let in the water is kept at a

warmish temperature. At the manufacturing town of Dundee they became at

one time a complete nuisance in some of the factories, having penetrated

into the steam 'and water pipes, occasionally bringing the works to a

complete standstill. In England the golden carp usually spawns between May

and July, the particular time being greatly regulated by the warmth of the

season. The time of spawning may be known by the change of habit which

occurs in this fish. It sinks at once into deep water instead of basking

on the top, as usual ; previous to which the fish are restive and quick in

their movements, throwing themselves out of the water, etc. It may be

stated here, to prevent disappointment, that golden carp seldom spawn in a

transparent vessel. A Mr. Mitchell of Edinburgh, however, brought out a

hatching in his shop aquarium, in the Lothian Road, but the fry escaped by

the waste pipe. When the spawn is hatched the fish are very black in

colour, some darker than others : these become of a golden hue, while

those of a lighter shade become silvercoloured. It is some time before

this change occurs, a portion colouring at the end of one year, and others

not till two or three seasons have come and gone. These beautiful

prisoners seldom live long in their crystal cells, although the prison is

beautiful enough, one would fancy :

" I ask, what warrant fixed them (like a spell

Of witchcraft fixed them) in the crystal cell ;

To wheel with languid motion round and round,

Beautiful, yet in mournful durance bound !"

Gold-fish ought not to be purchased except from some

very respectable dealer. I have known repeated cases where the whole of

the fish bought have died within an hour or two of being taken home. These

golden carp, which are reared for sale, are usually spawned and bred in

warmish water, and they ought in consequence to be acclimatised or

"tempered" by the dealer before they are parted with. Parties buying ought

to be particular as to this, and ascertain if the fish they have bought

have been tempered.

Returning to the common carp, I can speak of it as

being a most useful pond-fish. It is a vegetarian, and may be classed

among the least carnivorous fishes; it feeds chiefly upon vegetables or

decaying organic matter, and very few of them prey upon their kind, while

some, it is thought, pass the winter in a torpid state. There is a rhyme

which tells us that

Turkeys, carp, hops, pickerel, and beer,

Came into England all in one year.

But this couplet must, I think, be wrong, as some of

these items were in use long before the carp was known ; indeed, it is not

at all certain when this fish was first introduced into England, or where

it was brought from, but I think it extremely possible that it was

originally brought here from Germany. In ancient times there used to be

immense ponds filled with carp in Prussia, Saxony, Bohemia, Mecklenburg,

and Holstein, and the fish was bred and brought to market with as much

regularity as if it had been a fruit or a vegetable. The carp yields its

spawn in great quantities, no fewer than 700,000 eggs having been found in

a fish of moderate weight (ten pounds) ; and, being a hardy

fish, it is easily cultivated, so that it would be profitable to breed in

ponds for the fishmarkets of populous places, and the fish-salesmen assure

us that there would be a large demand for good fresh carp. It is

necessary, according to the best authorities, to have the ponds in suites

of three - viz. a spawning-pond, a nursery, and a receptacle for the large

fish-and to regulate the numbers of breeding fish according to the surface

of water. It is not my intention to go minutely into the construction of

carp-ponds ; but I may be allowed to say that it is always best to select

such a spot for their site as will give the engineer as little trouble as

possible. Twelve acres of water divided into three parts would allow a

splendid series of ponds-the first to be three acres in extent, the second

an acre more, and the third to be five acres ; and here it may be again

observed that, with water as with land, a given space can only

yield a given amount of produce, therefore the ponds must not be

overstocked with brood. Two hundred carp, twenty tench, and twenty jack

per acre is an ample stock to begin breeding with. A very profitable

annual return would be obtained from these twelve acres of water ; and, as

many

country gentlemen have even larger sheets than twelve

acres, I recommend this plan of stocking them with carp to their

attention. There is only the expense of construction to look to, as an

under-keeper or gardener could do all that was necessary in looking after

the fish. A gentleman having a large estate in Saxony, on which were

situated no less than twenty ponds, some of them as large as twenty-seven

acres, found that his r, stock of fish added greatly

to his income. Some of the carp weighed fifty pounds each, and upon the

occasion of draining one of his ponds, a supply of fish weighing five

thousand pounds was taken out ; and for good carp it would be no

exaggeration to say that sixpence per pound weight could easily be

obtained, which, for a quantity like that of this Saxon gentleman, would

amount to a sum of £125 sterling. Now, I have the authority of an eminent

fish-salesman for stating that ten times the quantity here indicated could

be disposed of among the Jews and Catholics of London in a week, and,

could a regular supply be obtained, an unlimited quantity might be sold.

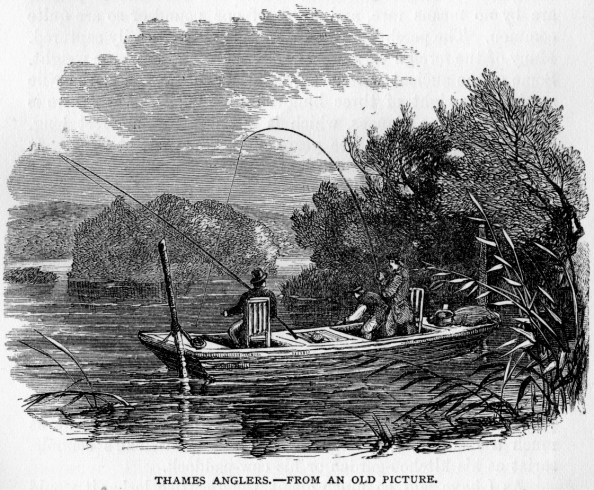

I have been writing about Highland streams and northern

lochs ; but the river scenery of England is, in its way, equally

beautiful, and no river is more charming than the Thames. It is a classic

stream, and its praises have been sung by the poets and celebrated by the

historian. After Mrs. S. C. Hall and Thorne, it were vain to repeat its

praises :

"Glide gently, thus for ever glide,

0 Thames ! that anglers all may see

As lovely visions by thy side,

As now, fair river, come to me.

Oh, glide, fair stream, for ever so

Thy quiet soul on all bestowing,

Till all our minds for ever flow

As thy deep waters are now flowing."

The total length of the river Thames is 215 miles, and

the area of the country it waters is 6160 square miles. It has as

affluents a great many fine streams, including the river Loddon, as also

the Wey and the Mole. I am not entitled to consider it here in its

picturesque aspects-my business with it is piscatorial, and I am able to

certify that it is rich in fish of a certain kind -

" The bright-eyed perch with fins of Tyrian dye,

The silver eel in shining volumes rolled,

The yellow carp in scales bedropp'd with gold,

Swift trout diversified with crimson stains,

And pike, the tyrants of the watery plains."

Considering that all its best fishing points are

accessible to an immense population, many of whom are afflicted with a

mania for angling, it is quite wonderful that there is a single fish of

any description left in it ; and yet there are several bands of honest

anglers who can fill occasional big baskets. I may be allowed just to run

over a few Thames localities, and note what fish may be taken from them.

Above Teddington at different places an occasional trout may be pulled

out, but, although the finest trout in the world may be got in the Thames,

they are, unfortunately, so scarce in the meantime, that it is hardly

worth while to lose one's time in the all but vain endeavour to lure them

from their home. Pike fishing or trolling will reward the Thames angler

better than trouting. There are famous pike to be taken every here and

there - in the deep pools and at the weirs : and, as the pike is

voracious, a moderately good angler, with proper bait, is likely to have

some sport with this fish. But the specialty of the Thames, so far at

least as most anglers are concerned, is the quantity of fish of the carp

kind which it contains, as also perch. This latter fish may be taken with

great certainty about Maidenhead, Cookham, Pangbourne, VVaIton, Labham,

and Wallingford Road ; and a kindred fish, the pope, in great plenty, may

be sought for in the same localities. Then the bearded barbel is found in

greater plenty in the Thames than anywhere else, and, as it is a fish of

some size and of much courage, it affords great sport to the angler. The

best way to take the barbel is with the " Ledger," and the best places for

this kind of fishing are the deeps at Kingston Bridge, Sunbury Lock,

Halliford, Chertsey Weir, and in the deeps at Bray, where many a time and

oft have good hauls of barbel been taken. The best times for the capture

of this fish are late in the afternoon or very early in the morning. Chub

are also plentiful in the Thames ; and Mr. Arthur Smith, who wrote a guide

to Thames anglers, specially recommended the island above Goring for chub,

also Marlow and the large island below Henley Bridge. This fish can be

taken with the fly, and gives tolerable sport. The roach is a fish that

abounds in all parts of the Thames, especially between Windsor and

Richmond ; and in the proper season - September and October-it will be

found in Teddington Weir, Sunbury, Blackwater, Walton Bridge, Shepperton

Lock, the Stank Pitch at Chertsey, and near Maidenhead, Marlow, and Henley

Bridges. At Teddington I may state that the dace is abundant, and there is

plenty of little fish of various kinds that can be had as bait at most of

the places we have named. In fact, in the Thames there is a superabundance

of sport of its kind, and plenty of accommodation for anglers, with wise

"professionals " to teach them the art ; and although the best sport that

can be enjoyed on this lovely stream is greatly different from the

trout-fishing of Wales or Scotland, it is good in its degree, and tends to

health and high spirits, and an anxiety to excel in his craft, as one can

easily see who ventures by the side of the water about Kew and Richmond.

" With hurried steps,

The anxious angler paces on, nor looks aside,

Lest some brother of the angle, ere he arrive,

Possess his favourite swim."

I come now to the perch, a well-known because common

fish, about which a great deal has been written, and which is easily taken

by the angler. There are a great number of species of this fish, from the

common perch of our own canals and lochs to the "lates" of the Nile, or

the beautiful golden-tailed mesoprion, which swims in the seas of Japan

and India, and flashes out brilliant rays of colour. The perch was

assiduously cultivated in ancient Italy, in the days when pisciculture was

an adjunct of gastronomy, and was thought to equal the mullet in flavour.

In Britain, the fish, left to its natural growth and no care being taken

to flavour it artificially, is surpassed for table purposes by the salmon

and the trout ; but perch being abundant afford plenty of good fishing.

The perch usually congregate in small shoals, and delight in streams, or

water with a clear bottom and with overhanging foliage to shelter them

from the overpowering heat of summer. These fish do not attain any

considerable weight, the one recorded as being taken in the Serpentine, in

Hyde Park, which weighed nine pounds, being still the largest on record.

Perch of three and four pounds are by no means rare, and those of one

pound or so are quite common. The perch is a stupid kind of fish, and

easily captured. Many of the foreign varieties of perch attain

an immense weight. Some of the ancient writers tell

us that the " lates" of the Nile attained a weight of three hundred pounds

; and then there is the vacti of the Ganges, which is often caught five

feet long. The perch, after it is three years old, spawns about May. It

may be described as rather a hardy fish, as we know it will live a long

time out of water, and can be kept alive among wet moss, so that it may be

easily transferred from pond to pond. Its hardy nature accounts for its

being found in so many northern lochs and rivers, as in the olden times of

slow conveyances it must have taken a long time to send the fish to the

great distances we know it must have been carried to. On the Continent,

living perch are a feature of nearly all the fishmarkets. The fish, packed

in moss and occasionally sprinkled with water, are carried from the

country to the cities, and if not sold are taken home and replaced in the

ponds. This particular fish, which is very prolific, might be " cultivated

" to any extent. Fishponds, although not now common, used to be at one

time as much a food-giving portion of a country gentleman's commissariat

as his kitchen-garden or his cow-paddock.

As I have said so much about the Scottish lochs, it

would be but fair to say a few words about those of England ; but in good

honest truth it would be superfluous to descant at the present day on the

beauties of Windermere, or the general lake scenery of Cumberland and

Westmoreland: it has been described by hundreds of tourists, and its

praises have been sung by its own poets-the lake poets. It is with its

fish that we have business, and honesty compels us to give the charr a bad

character. It is not by any means a game fish, so far as sport is

concerned ; nor is it great in size or rich in flavour. But potted charr

is a rare breakfast delicacy. This fish, which is said by Agassiz to be

identical with the ombre chevalier of Switzerland, is rarely found to

weigh more than a pound ; specimens are sometimes taken exceeding that

weight, but they are scarce. The charr is found to be pretty general in

its distribution, and is found in many of the Scottish lochs. It spawns

about the end of the year, some of the varieties depositing their eggs in

the shallow parts of the lake, while others proceed a short way up some of

the tributary streams. In November great shoals of charr may be seen in

the rivers Rothay and Brathay, particularly the latter, with the view of

spawning. The charr, we are told by Yarrell, afford but scant amusement to

the angler, and are always to be found in the deepest parts of the water

in the lochs which they inhabit. "The best way to capture them is to trail

a very long line after a boat, using a minnow for a bait, with a large

bullet of lead two or three feet above the bait to sink it deep in the

water ; by this mode a few charr may be taken in the beginning of summer,

at which period they are in the height of perfection both in colour and

flavour."

As I am on the subject of anglers' fishes, the reader

will perhaps allow me to suggest that "no end of sport" may be obtained in

the sea; that capital sea-angling may be enjoyed all the year round, and

all round the British coasts ; and that there are fighting fishes in the

waters of the great deep that will occasionally try both the cunning and

the nerve of the best anglers. The greatest charm of sea-angling, however,

lies in its simplicity, and the readiness with which it can be engaged in,

together with the comparatively homely and inexpensive nature of the

instruments required. A party living at the seaside can either fish off

the rocks or hire a boat, and purchase, or obtain on loan (for a slight

consideration) such simple tackle as is necessary ; though it must not be

too simple, for even sea-fish will not stand the insult of supposing they

can be caught as a matter of course with anything ; and as the larger

kinds of hooks are often scarce at mere fishing villages, it is better to

carry a few to the scene of action. '

"Well then, what sport does the sea afford?" will most

likely be the first question put by those who are unacquainted with

sea-angling. I answer, Anything and everything in the shape of fish or

sea-monster, from a sprat to a whale. This is literally true. It is not an

unfrequent occurrence for tourists in Orkney, or other places in Scotland,

to assist at a whale battue; and some of my readers may remember a very

graphic description of an Orcadian whale-hunt, given in Blackwood's

Magazine, by the late Professor Aytoun, who was Sheriff and Admiral of

Orkney. The kind of sea-fish, however, that are most frequently taken by

the angler, both on the coasts of England and Scotland, are the whiting,

the common cod, the beautiful poor or power cod, and the mackerel ; there

is also the abundant coal-fish, or sea-salmon as I call it, from its

handsome shape. This fish is taken in amazing quantities, and in all its

stages of growth. It is known by various names, such as sillock, piltock,

cudden, poddly, etc. ; indeed most of our fishes have different names in

different localities ; but I shall keep to the proper name so as to avoid

mistakes. The merest children are able, by means of the roughest

machinery, to catch any quantity of young coal-fish ; they can be taken in

our harbours, and at the sea-end of our piers and landing -places. The

whiting is also very plentiful, so far as angling is concerned, as indeed

are most of the Gadidae. It feeds voraciously, and will seize upon

anything in the shape of bait ; several full-grown pilchards have been

more than once taken from the stomach of a four-pound fish. Whiting can be

caught at all periods of the year, but it is of course most plentiful in

the breeding season, when it approaches the shores for the purpose of

depositing its spawn-that is in January and February. The common cod-fish

is found on all parts of our coast, and the sea-anglers, if they hit on a

good locality-and this can be rendered a certainty-are sure to make a very

heavy basket.

The pollack, or, as it is called in Scotland, lythe,

also affords capital sport ; and the mackerel-herring and conger-eel can

be captured in considerable quantities. I can strongly recommend lythe-fishing

to gentlemen who are blases of salmon or pike, or who do not find

excitement even among the birds of lone St. Kilda. Then, as will

afterwards be described, there is the extensive family of the flat fish,

embracing brill, plaice, flounders, soles, and turbot. The latter is quite

a classic fish, and has long been an object of worship among gastronomists

; it has been known to attain an enormous size. Upon one occasion an

individual, which measured six feet across, and weighed one hundred and

ninety pounds, was caught near Whitby. The usual mode of capturing flat

fish is by means of the trawl-net, but many varieties of them may be

caught with a hand-line. A day's sea-angling will be chequered by many

little adventures. There are various minor monsters of the deep that vary

the monotony of the day by occasionally devouring the bait. A

tadpole-fish, better known as the sea-devil or " the angler," may be

hooked, or the fisher may have a visit from a hammer-headed shark or a

pile-fish, which adds greatly to the excitement ; and if " the dogs"

should be at all plentiful, it is a chance if a single fish be got out of

the sea in its integrity. So voracious and active are this species of the

Squalidae, that I have often enough pulled a mere skeleton into the boat,

instead of a plump cod of ten or twelve pounds weight.

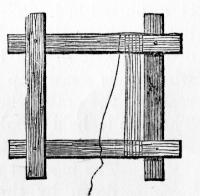

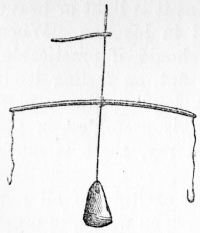

I shall now say a few words about the machinery of

capture. The tackle in use for handline sea-fishing is

much

the same everywhere, and that which I describe will suit almost any

locality. It consists of a frame of four pieces of wood-work about a foot

and a half in length, fastened together in the shape of such a machine as

ladies use for certain worsted work. Round this is wound a thin cord,

generally tanned, of from ten to twenty fathoms in length. To the extreme

end of this line is attached a leaden sinker, the weight of which varies

according as the current much

the same everywhere, and that which I describe will suit almost any

locality. It consists of a frame of four pieces of wood-work about a foot

and a half in length, fastened together in the shape of such a machine as

ladies use for certain worsted work. Round this is wound a thin cord,

generally tanned, of from ten to twenty fathoms in length. To the extreme

end of this line is attached a leaden sinker, the weight of which varies

according as the current

of

the tide is slow or rapid. About two feet above the sinker is a cross

piece of whalebone or iron, to the extremities of which the strings on

which the hooks are dressed are attached. Sometimes a third hook is

affixed to an outrigger, about two feet above the other hooks. The length

of the cords to which the lower hooks are attached should be such as to

allow them to hang about six inches higher than the bottom of the sinker.

In some parts of the Western Highlands a rod consisting of thin fir is

used, but from the length of line required it is rather a clumsy

instrument, as after the fish has been struck the rod has to be laid down

in the boat, and the line to be hauled in by hand. of

the tide is slow or rapid. About two feet above the sinker is a cross

piece of whalebone or iron, to the extremities of which the strings on

which the hooks are dressed are attached. Sometimes a third hook is

affixed to an outrigger, about two feet above the other hooks. The length

of the cords to which the lower hooks are attached should be such as to

allow them to hang about six inches higher than the bottom of the sinker.

In some parts of the Western Highlands a rod consisting of thin fir is

used, but from the length of line required it is rather a clumsy

instrument, as after the fish has been struck the rod has to be laid down

in the boat, and the line to be hauled in by hand.

As to bait it is quite impossible to lay down any

strict rule. The bait which is the favourite in one bay or bank is scouted

by the fish of other localities. At times almost anything will do :

numbers of mackerel have been taken with a little bit of red cloth

attached to the hook ; on certain occasions the fish are so hungry that

they will swallow the naked iron On the English coasts, and among the

Western Islands of

Scotland,

the most deadly bait that is used is boiled limpets, which require to be

partially chewed by the fisher before placing them on the hooks; in other

places mussels are the favourites, and in others the worms procured among

the mud of the shore. The limpet has this one advantage, that it is easily

fixed on the hook, and keeps its hold tenaciously. A very excellent bait

for the larger kinds of fish is the soft parts of the body of small crabs,

which are gathered for that purpose at low tide under the stones; a good

place for procuring them is a mussel-bed. The best time for fishing is

immediately before ebb or flow. The hooks being baited, the line is run

over the side of the boat until the lead touches the bottom, when it is

drawn up a little, so as to keep the baits out of reach of the crabs who

gnaw and destroy both bait and tackle. The line is held firmly and lightly

outside the boat, the other hand, inside the boat, also having a grip of

the line. The moment a fish is felt to strike, the line is jerked down by

the hand inside, thus bringing it sharply across the gunwale and fixing

the hook. A little experience will soon enable the angler to determine the

weight of the fish, and according as it is light or heavy must he quickly

or slowly haul in his line. When the fish reaches the surface, he should,

if practicable, seize it with his hand, as it is apt, on feeling itself

out of water, to wriggle off. A landing-clip or gaff, such as is used in

salmon-fishing, is useful, as, in the event of hooking a conger or a ray,

there is much difficulty, and even some danger. Scotland,

the most deadly bait that is used is boiled limpets, which require to be

partially chewed by the fisher before placing them on the hooks; in other

places mussels are the favourites, and in others the worms procured among

the mud of the shore. The limpet has this one advantage, that it is easily

fixed on the hook, and keeps its hold tenaciously. A very excellent bait

for the larger kinds of fish is the soft parts of the body of small crabs,

which are gathered for that purpose at low tide under the stones; a good

place for procuring them is a mussel-bed. The best time for fishing is

immediately before ebb or flow. The hooks being baited, the line is run

over the side of the boat until the lead touches the bottom, when it is

drawn up a little, so as to keep the baits out of reach of the crabs who

gnaw and destroy both bait and tackle. The line is held firmly and lightly

outside the boat, the other hand, inside the boat, also having a grip of

the line. The moment a fish is felt to strike, the line is jerked down by

the hand inside, thus bringing it sharply across the gunwale and fixing

the hook. A little experience will soon enable the angler to determine the

weight of the fish, and according as it is light or heavy must he quickly

or slowly haul in his line. When the fish reaches the surface, he should,

if practicable, seize it with his hand, as it is apt, on feeling itself

out of water, to wriggle off. A landing-clip or gaff, such as is used in

salmon-fishing, is useful, as, in the event of hooking a conger or a ray,

there is much difficulty, and even some danger.

In fishing for lythe - the most exciting of all sea

angling-a very strong cord is used, on which, in order to prevent the

fouling of the line, one or two stout swivels are attached. The hooks also

cannot be too strong ; those used for cod or ling fishing are very

suitable. The baits in general use are the body of a small eel, about half

a foot in length, skinned and tied to the shaft ; or a strip of red cloth,

or a red or white feather similarly attached. A piece of lead is fixed on

the line at a short distance above the hook.

The boat must be rowed or sailed at a moderate rate,

and from five or ten fathoms of the line allowed to trail behind. The boat

end of the line should be turned once or twice round the arm, and held

tightly in the hand ; if the line were fastened to the boat, there is

every chance that a large lythe - and they are frequently caught upwards

of thirty pounds weight-would snap the tackle. The fish, when hooked,

gives considerable play, and rather strongly objects to being lifted into

the boat. The clip or gaff is in this case always necessary. In fishing

for lythe, mackerel and dogfish are not unfrequently caught. The best

place for prosecuting this sport is in the neighbourhood of a rocky shore

; and the best times of the day are the early morning and evening. This

fish will also take readily during any period of a dull but not gloomy

day.

The most amusing kind of sea-angling is fly-fishing for

small lythe and saithe (coal-fish). The tackle is exceedingly simple: a

rod consisting of a pliant branch about eight feet in length ; a line of

light cord of the same length, and a little hook roughly busked with a

small white, red, or black feather. The fly is dragged on the surface as

the boat is rowed along, and the moment the fish is struck it is swung

into the boat. The fry of the lythe and saithe may also be fished for from

rocks and pier-heads, using the same tackle. A very ingenious plan for

securing a number of these little fish is carried on in the Firth of Clyde

and elsewhere. A boat similar in shape to a salmoncoble, with a crew of

two-one to row and one to fish-goes out along the shore in the evening,

when the sea is perfectly calm or nearly so. The fisher has charge of

half-a-dozen rods or more, similar to the one already mentioned. These

rods project across the square stern of the boat, and their near ends are

inserted into the interstices of a seat of wattled boughs, on which the

fisher sits, not steadily, but bumping gently up and down, communicating a

trembling motion to the flies. The course of the coble is always close in

shore, and, if the fish are taking well, the same ground may be fished

over many times during the course of the evening.

As to set-line-fishing, it can only be practised in

places where the tide recedes to a considerable distance. The cord used is

of no defined length, and at certain distances along its entire extent are

affixed corks to prevent the hooks sinking in the sand or mud. The

shore-end is generally anchored to a stone, and the further end fastened

to the top of a stout staff firmly fixed in the beach, and generally

attached also to a stone to prevent it drifting ashore in the event of

being loosened from its socket. From the staff almost to the shore, hooks

are tied along the line at distances of a yard. The hooks are baited at

low tide, and on the return of next low tide the line is examined. This is

neither a satisfactory nor sure method of fishing, as many of the fish

wriggle themselves free, and clear the hook of the bait, and many, after

being caught, fall a prey to dogfish, etc., so that the disappointed

fisher, on examining his line, too often finds a row of baitless hooks,

alternating with the half-devoured bodies of haddocks, flounders, saithe,

and other shore fish.

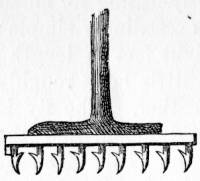

I

may just name another mode of obtaining sport, which is by spearing flat

fish, such as flounders, dab, plaice, etc. No rule can be laid down on

this method of fishing. It has been carried on successfully by means of a

common pitchfork, but some gentlemen go the length of having fine spears

made for the purpose, very long and with very sharp prongs ; others,

again, use a three-pronged farm-yard "graip," which has been known to do

as much real work as more elaborate utensils specially contrived for the

purpose. The simplest directions I can give to those who try this style of

fishing are just to spear all the fish they can see, but the general plan

is to stab in the dark with the kind of instrument delineated above. At

the mouths of most of the large English rivers there is usually abundance

of all the minor kinds of flat fish. I

may just name another mode of obtaining sport, which is by spearing flat

fish, such as flounders, dab, plaice, etc. No rule can be laid down on

this method of fishing. It has been carried on successfully by means of a

common pitchfork, but some gentlemen go the length of having fine spears

made for the purpose, very long and with very sharp prongs ; others,

again, use a three-pronged farm-yard "graip," which has been known to do

as much real work as more elaborate utensils specially contrived for the

purpose. The simplest directions I can give to those who try this style of

fishing are just to spear all the fish they can see, but the general plan

is to stab in the dark with the kind of instrument delineated above. At

the mouths of most of the large English rivers there is usually abundance

of all the minor kinds of flat fish.

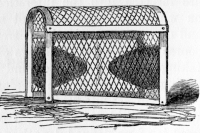

Lobsters

and crabs can be taken at certain rocky places of the coast; mussels can

be picked from the rocks, and cockles can be dug for in the sand. Shrimps

can also be taken, and various other wonders of the sea and its shores may

be picked up. After a storm a great number of curious fishes and shells

may be gathered, and some of these are very valuable as specimens of

natural history. The apparatus for capturing lobsters and crabs is like a

cage, and is generally made of wicker work, with an aperture at the top or

the side for the animal to enter by ; it can be baited with any sort of

garbage that is at hand. Having been so baited, the lobster-pot is sunk

into the water, and left for a season, till, tempted by the mess within,

the game enters and is caged. Those who would induce crabs to enter their

pots must set them with fresh bait; lobsters, on the other hand, will look

at nothing but garbage. Very frequently rockcod, saithe, and other fish,

are found to have entered the pots, intent both on foul and fresh food.

Shell-fish for bait can be taken by means of a wooden box or old wicker

basket sunk near a rocky place, and filled with garbage of some kind ; the

whelks and small crabs are sure to patronise the mess extensively, and can

thus be obtained at convenience. It is impossible to tell in the limits of

a brief chapter one half of the fishing wonders that can be accomplished

during a sojourn at the sea-side. A visit to some quaint old fishing town,

on the recurrence of " the year's vacation sabbath," as some of our poets

now call the annual month's holiday, might be made greatly productive of

real knowledge ; there are ten thousand wonders of the shore which can be

studied besides those laid down in books. Lobsters

and crabs can be taken at certain rocky places of the coast; mussels can

be picked from the rocks, and cockles can be dug for in the sand. Shrimps

can also be taken, and various other wonders of the sea and its shores may

be picked up. After a storm a great number of curious fishes and shells

may be gathered, and some of these are very valuable as specimens of

natural history. The apparatus for capturing lobsters and crabs is like a

cage, and is generally made of wicker work, with an aperture at the top or

the side for the animal to enter by ; it can be baited with any sort of

garbage that is at hand. Having been so baited, the lobster-pot is sunk

into the water, and left for a season, till, tempted by the mess within,

the game enters and is caged. Those who would induce crabs to enter their

pots must set them with fresh bait; lobsters, on the other hand, will look

at nothing but garbage. Very frequently rockcod, saithe, and other fish,

are found to have entered the pots, intent both on foul and fresh food.

Shell-fish for bait can be taken by means of a wooden box or old wicker

basket sunk near a rocky place, and filled with garbage of some kind ; the

whelks and small crabs are sure to patronise the mess extensively, and can

thus be obtained at convenience. It is impossible to tell in the limits of

a brief chapter one half of the fishing wonders that can be accomplished

during a sojourn at the sea-side. A visit to some quaint old fishing town,

on the recurrence of " the year's vacation sabbath," as some of our poets

now call the annual month's holiday, might be made greatly productive of

real knowledge ; there are ten thousand wonders of the shore which can be

studied besides those laid down in books.

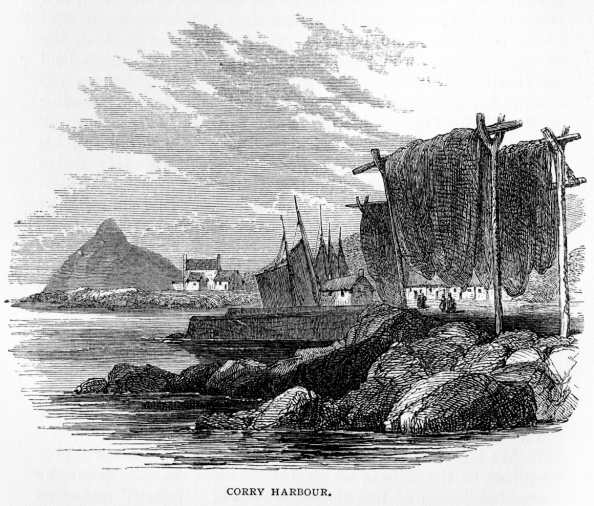

As will be noted, I have avoided as much as possible

the naming of localities, preferring to state the general practice. In all

seaside towns and fishing villages there are usually three or four old

fishermen who will be glad to do little favours for the curious in fish

lore-to hire out boats, give the use of tackle, and point out good

localities in which to fish. For such as have a few weeks at their

disposal, I would suggest the western sea-lochs of Scotland as affording

superb sport in all the varieties of sea-angling. Fish of all kinds, great

and small, are to be found in tolerable quantity, and there is likewise

the still greater inducement of fine scenery, cheap lodgings, and moderate

living expenses. But the entire change of scene is the grand medicine ;

nothing would do an exhausted London or Manchester man more good than a

month on Lochfyne, where he could not only angle in the great water for

amusement, but also watch the commercial fishers, and enjoy the finely-flavoured

herring of that loch as a portion of his daily food. If persons in search

of sea-angling wish to combine the enjoyment of picturesque scenery with

their pleasant labours on the water, they cannot do better than select the

rural village of Corry, on the Island of Arran, as a centre from which to

conduct their operations.

Our angler, having arrived at Glasgow, can go down the

Clyde by steamboat direct to Arran. There is another and a quicker way -

viz. by railway to Ardrossan and steamboat to Brodick, but most strangers

prefer the river ; and let me say here, without fear of contradiction,

there is no pleasure river equal to the Clyde, especially as regards

accessibility. The steamers from Glasgow peer at stated intervals into

every nook and cranny of the water, and, on the Saturdays especially,

deposit perfect armies of people at various towns and villages below

Greenock, who are thus enabled to pass the Sunday in the bright open air

by the clear waters of this great stream. Any kind of lodging is put up

with for the sake of being " down the water ;" and all sorts of

people-merchants even of high degree, and " Glasgow -bodies " of lower

social standing-are contented, chiefly no doubt at the instigation of

their better halves, to sojourn in places that when at home they would

think quite unsuitable for even the Matties of their households. The banks

of the Clyde have become wonderfully populous within the last twenty-five

years-villages have expanded into towns, hamlets have grown into villages,

and single cottages into hamlets. Now the railway to Greenock is

insufficient as a daily travelling aid to persons whose half-hours are of

large commercial value ; and as a consequence, a new line of rails has

been constructed to come upon the water at Wemyss Bay, about twelve miles

below Greenock. To your thorough business man time is money, and if lie is

alternately able to leave his place of business and his place of pleasure

half-an-hour later each way, he is all the better pleased with both. To

speculators in want of an idea I would say : Rush to the Clyde, and buy up

every inch of land that can be had within a mile of the water, build upon

it, and from the half million of human beings who tenant Glasgow and the

surrounding towns I will engage to find two competing occupants for every

house that can be put up. Building has progressed even in Arran, and this

too despite the late Duke of Hamilton's dislike to strangers, so that

there is now a population on the island of about 7000. A friend of mine

says that such an important entity as a duke has no right to do as he

likes with his own, and consequently that Arran ought to be built upon,

and blackcocks and other game birds be left to take their chance. Even

with such limited accommodation as can be now obtained, Arran is a

delightful summer residence ; were it to be generally built upon, it would

realise from ground-rents alone an annual fortune to his Grace the Duke of

Hamilton, who owns the greater part of it, and he might have capital

shooting into the bargain.

Arran, I may state to all who are ignorant of the fact,

is a very paradise for geologists ; and amateur globe-makers-persons 'who

think they are better at constructing worlds than the Great Architect who

preceded them all-are particularly fond of that island, being, as they

suppose, quite able to find upon it materiel sufficient for the

erection of the largest possible " theories." Figures, it is said, can be

made to prove either side of a cause ; so can stones. Each geologist can

build up his own pet world from the same set of rocks; and so active

geologists proceed to stucco over with their own compositions" adumbrate "

a friend calls the process-the sublime works of the greatest of all

designers. None of the sciences have given rise to so much controversy as

the science of geology. I make no pretensions to much geologic knowledge,

although I do know a little more than the man who wondered if the granite

boulders which lie saw on a brae-side were oil their way up or down the

hill, and argued that it was a moot point. What I would like to see would

be a good work oil geology, divested entirely of the learned and

scientific slang which usually makes such books entirely useless to

ninety-nine out of every hundred persons who attempt to read them. I would

like, moreover, a work that would not bully us with a ready-made theory.

We had been lauded from the steamboat on a massive grey

boulder, on the sides of which, thick as was the atmosphere, we observed

dozens of limpets and crowds of "buckies," and other sea-ware, giving us

token of ample employment when we could obtain leisure for a more minute

survey of the rocks and stray stones which sprinkle the sea-beach of

Corry. In the meantime, that is just after landing, the great, the

momentous question on this and every other Saturday night is-Is

the inn full q. A hurried scramble over the

jagged stones, and a rush past the very picturesque residence of Mr.

Douglas' pigs, brought us to the inn, and at once decided the question.

Mrs. Jamison, the landlady, shook her lawn-bedizened head-the inn, alas,

was full,

overflowing in fact, for a gentleman had engaged the coach-house ! It was

feared, too, that every house in the village was in a like predicament,

and further inquiry soon confirmed this to us rather awful statement, and

so I was left standing at the inn-door, with a bitingly shrewd companion,

to solve this problem-Given the barest possible accommodation throughout

all Corry for only forty-eight strangers, how to shake fifty into the

village, so that each might have somewhere to lay his head ?

This is a problem, I suspect, that few can answer. What

was to be done ? The steamboat had gone !Were we then to tramp on to

Brodick, with more than a suspicion of a rainy night in the moist

atmosphere, or try a shake-down of clean straw in a lime quarry ? It might

have come to that, and as both of us had before then camped out for a

night by the sheltered side of a haystack, we might have arranged,

fortified by the aid of a dram, or perhaps two, to pass a tolerable night

in the lime cavern beside a very canny-looking horse-of-all-work that we

caught a glimpse of through the gloom of the place while peeping into it.

It fortunately occurred that a modest maiden lady, a

very " civil-spoken " woman indeed, by name Grace Macalister, had been

disappointed of two Glasgow gentlemen, who had engaged her whole house,

and so the two benighted travellers from the east were accepted, at the

instigation of the late Air. Douglas, a wellknown man in Corry, in lieu of

them. Taking possession of our lodgings at once, we formed ourselves into

a committee of supply, which resulted in a prompt expenditure of a sum of

six shillings and threepence, the particulars of which, for the benefit of

my readers, and to show how primitive we had all at once become, I beg to

subjoin-namely, bread, 7d. ; mutton; 2s. 4d. ; butter, 62d. ; tea, 6d. ;

sugar, 3d. ; milk, 2d. ; herring, 2d. This sum, with

eighteenpence added for whisky, threepence for potatoes, and one penny for

a candle, represented the total commissariat expenses of two persons in

Corry for five wholesome but homely meals. Our bed cost us one shilling

each per night, and our attendance and washing were charged at tile rate

of a shilling a day, so long as we used the Hotel Macalister, but even

this did not very much swell the grand total of the bill, which, at such

rates, was by no means heavy at the end of our holiday ramble over Arran,

especially when it is considered that the Arran season does not very

greatly exceed one hundred days. Our quarters were certainly primitive

enough--namely, half of a thatched cottage, or rather hut we may call it,

consisting of one apartment containing two beds, four chairs, a small

table, and a little cupboard. The beds were curtained by a series of blue

striped cotton fragments of three different patterns of all old Scotch

kind, and the walls were papered with five different kinds of paper ; but

the low roof was the greatest treat of all-it was covered with old numbers

of the Witness newspaper, at the time when it was edited by Hugh

Miller, and these had, no doubt, been left in the cottage by previous

travellers. The floor was covered with fragments of canvas laid down as a

carpet. Many tourists would perhaps turn up their noses at this humble

cottage, but to my friend and myself it was a delightful change.

I have not space in which to particularise all the

beauties of Arran, but I must say a word or two about Glen Sannox. Near

the golden beach of Sannox Bay is situated the solitary churchyard of

Corry, with its long grass waving rank over the graves, and its borders of

fuchsias laden with brilliant blossoms. There was, we observed, on peeping

over the wall, a new-made grave, that of an orphan girl who had been

drowned while bathing. Passing the churchyard-there was once a church at

the place, but all trace of it, save one stone built into the wall of the

churchyard, has long passed away-we came upon a brawling stream, which led

us up to the ruins of what had been a Barytesmill. The stones lay around

in great masses, as if they had been suddenly undermined by the passing

stream, and had fallen cemented as they stood. In a year or two they will

be grown over with weeds, and in a century hence some persons may

ingeniously speculate on the ruins, and give a learned disquisition as to

the building that once stood there, and its uses. My friend and I wondered

what it had been, but an old man told us all about it ; and strange to

say, in the course of conversation, we found this old resident reciting

scraps of Ossian's poems. He told us, too, that the bard had died in the

very parish in which we were standing. He believed Ossian to have been a

priest and teacher of the people, and this was an idea that was quite new

to us. We had heard before, or rather read, that the poet was by some

esteemed a great warrior, and by others a necromancer-perhaps to esteem

him a teacher is right enough ; his poems, at any rate, were at one time

as familiar in the mouths of the West Highlanders as household words.

The scenery of Arran would certainly inspire a poet. As

we penetrated into Glen Sannox it became most interesting, whether we

noted the brawling and bubbling brook, or the rich carpet of heath and

wild flowers upon which we trod. The luxuriance of its wild flowers is

remarkable, and of its rabbits equally so. As we proceed up the glen, the

lofty hills with their granitic scars frown down upon us, and one with a

coroneted brow looks kingly among the others, as the mists float upon

their shoulders, like a waving mantle, and with their bold and rugged

precipices they seem as if they had just been suddenly shot out from the

bosom of the earth. Glen Sannox is sublime indeed ; its magnitude is

remarkable, and it is so hemmed in with hills as to look at once, even