animals to fatten upon nothing. However, they go about

this in a very economic way, for the same water that grows the fish also

grows the food on which they are fed. This is chiefly the aquadelle, a

tiny little fish which is contained in the lakes in great numbers, and

which, in its turn, finds food in the insect and vegetable world of the

lagoons. Other fish are bred as well as the eel—viz, mullet, plaice, etc.

On the 2d day of February the year of Comacchio may be said to begin, for

at that time the montee commences, when may be seen ascending up

the Reno and Volano mouths of the Po from the Adriatic a great series of

wisps, apparently composed of threads, but in reality young eels; and as

soon as one lot enters, the rest, with a sheeplike instinct, follow their

leaders, and hundreds of thousands pass annually from the sea to the

waters of the lagoon, which can be so regulated as in places to be either

salt or fresh as required. Various operations connected with the working

of the fisheries keep the people in employment from the time the

entrancesluices are closed, at the end of April, till the commencement of

the great harvest of eel-culture, which lasts from the beginning of August

till December. The engraving represents one of the fishing-places of the

lagoon.

No country has, taking into account size and

population, been more industrious on the seas than Scotland-the most

productive fishery of the country having been that for herring. There is

no consecutive historical account of the progress of the herring-fishery.

The first really authentic notice we have of a trade in herrings is nine

hundred years old, when it is recorded that the Scots exported herrings to

the Netherlands, and there are indications that even then a considerable

fishery for herrings existed in Scotland; and prior to that date Boethius

alludes to Inverlochy as an important seat of commerce, and persons of

intelligence consider that town to have been a resort of the French and

Spaniards for the purchase of herring and other fishes. The pickling and

drying of herrings for commerce were first carried on by the Flemings.

This mode of curing fish is said to have been discovered by William

Benkelen of Biervlet, near Sluys, who died in 1397, and whose memory was

held in such veneration for that service that the Emperor Charles V. and

the Queen of Hungary made a pilgrimage to his tomb. Incidental notices of

the herring-fishery are contained in the records of the monastery of

Evesham, so far back as the year 709, and the tax levied on the capture of

herrings is noticed in the annals of the monastery of Barking as

herring-silver. The great fishery for herrings at Yarmouth dates from the

earliest Anglo-Saxon times, and at so early a period as the reign of Henry

I. it paid a tax of 10,000 fish to the king. We are told that the most

ancient records of the French herring fishery are not earlier than the

year 1020, and we know that in 1088 the Duke of Normandy allowed a fair to

be held at Fecamp during the time of this fishery, the right of holding it

being granted to the Abbey of the Holy Trinity. The Yarmouth fishery, even

in these early times, was a great success-as success was then understood.

Edward III, did all he could to encourage the fishery at that place. In

1357 he got his parliament to lay down a body of laws for the better

regulation of the fisheries, and the following year sixty lasts of herring

were shipped at Portsmouth for the use of his army and fleet in France. In

1635 a patent was granted to Mr. Davis for gauging red-herrings, for which

Yarmouth was famed thus early, at a certain price per last ; his duty was,

in fact, to denote the quality of the fish by affixing a certain seal ;

this, so far as we know, is the first indication of

the brand system. His Majesty Charles II., being interested in the

fisheries, visited Yarmouth in company with the Duke of York and others of

the nobility, when lie was handsomely entertained, and presented with four

golden herrings and a chain of considerable value.

Several of the kings of Scotland were zealous in aiding

the fisheries, but the death of James V., and the subsequent religious and

civil commotions, put a stop for a time to the progress of this particular

branch of trade, as well as to every other industrial project of his time.

In 1602 his successor on the throne, James VI., resumed the plans which

had been chalked out by his grandfather. Practical experiments were made

in the art of fishing, fishing towns were built in the different parts of

the Highlands, and persons well versed in the practice were brought to

teach the ignorant natives; but as the Highlanders were jealous of these

"interlopers," very slow progress was made; and again the course of

improvement was interrupted by the king's accession to the throne of

England and the union of the two Crowns. During the remainder of James's

reign little progress was made in the art of fishing, and we have to pass

over the reign of Charles I., and wait through the troublous times of the

Protectorate till we have Charles II, seated on the throne, before much

further encouragement is decreed to the fisheries. Charles II, aided the

advancement of this industrial pursuit by appointing a Royal Council of

Fishery, in order to the establishment of proper laws and regulations for

the encouragement of those engaged in this branch of our commerce.

After this period the British trade in fish and

knowledge of the arts of capture expanded rapidly. It is, said, as I have

already stated, that during our early pursuit of the fishery the Dutch

learned much from us, and that, in fact, while we were away founding the

Greenland whale-fishery, the people of Holland came upon our seas and

robbed us of our fish, and so obtained a supremacy in the art that lasted

for many years. At any rate, whatever the Dutch accomplished, we were

particularly industrious in fishing. Our seas were covered with busses of

considerable tonnage-the average being vessels of fifty tons, with a

complement of fourteen men and a master. The mode of fishing then was to

sail with the ship into the deep sea, and. then, leaving the vessel as a

rendezvous, take to the small boats, and fish with them, returning to the

large vessel to carry on the cure. The same mode of fishing, with slight

modifications, is still pursued at Yarmouth and some other places in

England.

Much has been written about the great cod-fishery of

Newfoundland: it has been the subject of innumerable treatises, Acts of

Parliament, and other negotiations, and various travellers have

illustrated the natural products and industrial capabilities of the North

American seas. The cod-fishery of Newfoundland undoubtedly affords one of

the greatest fishing industries the world has ever seen, and has been more

or less worked for three hundred and sixty years. Occasionally there is a

whisper of the cod grounds of Newfoundland being exhausted, and it would

be no wonder if they were, considering the enormous capture of that fish

that has constantly been going on during the period indicated, not only by

means of various shore fisheries, but by the active American and French

crews that are always on the grounds capturing and curing. Since the time

when the Red Indian lay over the rocks and transfixed the codfish with his

spear, till now, when thousands of ships are spreading their sails in the

bays and surrounding seas, taking the fish with ingenious instruments of

capture, myriads upon myriads of valuable cod have been taken from the

waters, although to the ordinary eye the supply seems as abundant as it

was a century ago. When my readers learn that the great bank from whence

is obtained the chief supply of codfish is nearly six hundred miles long

and over two hundred miles in breadth, it will afford a slight index to

the vast total of our sea wealth, and to the enormous numbers of the finny

population of this part of our seas, the population of which, before it

was discovered, must have been growing and gathering for centuries ; but

when it is further stated-and this by way of index to the extent of this

great food-wealth-that Catholic countries alone give something like half a

million sterling every year for the produce of these North American seas,

the enormous money value of a well-regulated fishery must become apparent

even to the most superficial observer of facts and figures. It is much to

be regretted that we are not in possession of reliable annual statistics

of the fisheries of Newfoundland, but there are so many conflicting

interests connected with these fisheries as to render it difficult to

obtain accurate statistics.

It is pleasant to think that the seas of Britain are at

the present time crowded with many thousand boats, all gleaning wealth

from the bosom of the waters. As one particular branch of sea industry

becomes exhausted for the season, another one begins. In spring we have

our white fisheries; in summer we have our mackerel; in autumn we have the

great herring-fishery; then in winter we deal in pilchards and sprats and

oysters; and all the year round we trawl for flat fish or set pots for

lobsters, or do some other work of the fishing in fact, we are

continually, day by day, despoiling the waters of their food

treasures. When we exhaust the inshore fisheries we proceed straightway to

the deep waters. Hale and strong fishermen sail hundreds of miles to the

white-fishing grounds, whilst old men potter about the shore, setting nets

with which to catch crabs, or ploughing the sand for prawns. At different

places we can note the specialties of the British fisheries. In Caithness-shire

we can follow the greatest herring-fleet in the world ; at Cornwall,

again, we can view the pilchard-fishery; at Barking we can see the

cod-fleet; at Hull there is a wealth of trawlers ; at Whitstable we can

make acquaintance with the oyster-dredgers; and at the quaint

fishing-ports on the Moray Firth, we can witness the manufacture of "Finnan

haddies," as at Yarmouth we can take part in the making of bloaters ; and

all round our coasts we can see women and children industriously gathering

shell-fish for bait, or performing other functions connected with the

industry of the sea-repairing nets, baiting the lines, or hawking the

fish, for fisherwomen are true helpmates to their husbands. At certain

seasons everything that can float in the water is called into

requisition-little cobles, gigantic yawls, trig schooners, are all

required to aid in the gathering of the sea harvest. Thousands of people

are employed in this great industry; betokening that a vast population

have chosen to seek bread on the bosom of the great deep.

Crossing the Channel, we may note that the general sea

fisheries of France are also being prosecuted with great vigour, and at

those places which have railways to bear away the produce with

considerable profit. All kinds of fish are caught on the French coasts

with much assiduity, and the coast-line of that country being enormous-in

length, reaching from Dunkirk to Bayonne, including sinuosities, it will

be considerably over 2000 kilometres - there is a great abundance of fish,

the only regret in connection with the food fisheries being that at those

places where the yield could be best obtained the fishing is but lazily

prosecuted, in consequence of the want of inland conveyance. From many of

the fishing villages there is no path to the populous inland cities, and

the fish is sold, as it used to be sold in Scotland before the days of

railways and other quick conveyances, by the wives of the fishermen, who

hawk the produce of the sea through the country. In such towns as Boulogne,

where there is a large resident population, and a constant accession of

English visitors as well, the demand for fish is constant and

considerable, and well supplied. In the department of the Pas de Calais

there are over 600 fishing-boats. In Boulogne harbour, which is the chief

port of the district, the English visitors will see a large number of

boats, chiefly trawls, and all who visit Boulogne have seen the fishwives,

if not dressed en fete, then in their work-a-day habits, doing hard

labour for their husbands or the tourists. Sea fish is scarce and dear

over most of inland France ; the prices in the market at Paris rule very

high for premier qualities, but in that gay capital there is apparently no

scarcity. Fish must be had, and fish can always be obtained, whenever

there is money to pay the price demanded. In fact, a glance at the fish

department of the grand marche would lead one to suppose that, next

to growing fruit and vegetables, catching fish was the great industry of

the country.

The modes of sea-fishing are so much alike in every

country that it is unnecessary to do more than just mention that the

French method of trawling is very similar to our own. But there are

details of fishing industry connected with that pursuit on the French

coasts that we are not familiar with in Britain. The neighbouring

peasantry, for instance, come to the seaside and fish with nets which are

called bas parc; and these are spread out before the tide is full,

in order to retain all the fish which are brought within their meshes. The

children of these land-fishers also work, although with smaller nets, at

these foreshore fisheries, while the wives poke about the sand for shrimps

and the smaller crustacea. These people thus not only ensure a supply of

food for themselves during winter, but also contrive during summer to take

as much fish as brings them in a little store of money.

By far the best place to study the economy of the

French fisheries is at the basin of Arcachon, 34 miles from Bordeaux.

There may be seen the small boat as well as the trawl fishery ; and, above

all, in the placid waters of the basin may be seen the model oyster-beds

of France-beds that rarely languish for lack of spat, which has seldom

been known to fail ; beds which produce a nice, fat, tasteful oyster,

placed in an inland sea that is prolific of many of the best food fishes,

and contains the finest grey mullet in the world. To those who are anxious

thoroughly to study the French mode of fishing, Arcachon has this

advantage, that it has a day as well as a night fishery, and is also one

of the most unique bathing-places in the whole of France. From the

balconies of one's hotel, or from the windows of the houses, the whole

industry of the basin may be observed daily and nightly ; but the best

plan for seeing a fishery is to take a part in it, to sail out in the

boats, and handle the trawl or other nets. The chief fishing quarter is at

the extreme east end of Arcachon, consisting of a cluster of wooden

houses, easily known as those of the fishermen, from the various apparatus

and articles of dress which are depending about, and from the "ancient and

fish-like smell" which prevails in their neighbourhood. No less than

thirteen hundred sailors find employment in and about the basin ; and

there are close on five hundred boats of all kinds, a number of them being

steam trawlers. The value of the fishery of which Arcachon is the

head-quarters is estimated at over 1,500,000f., exclusive of the revenue

derived from the oyster-beds. In the basin there are lots of fish of all

kinds, both round and flat, capital soles in tolerable abundance, and very

excellent mullet, both red and grey ; there are also occasional takes of

sardines, which fish is locally known as the royan. The steamboats

referred to go out into the Bay of Biscay to trawl, and carry also an

immense net, which the men call a trammel ; it is cumbrous and heavy, and

can only be drawn in by using the steam-engine of the ship. Great "takes"

of mullet are occasionally got at Arcachon by watching and hemming in

shoals which get lost in the numerous creeks that indent the shores of the

basin. There is a ready market for all the fish that can be taken in

Bordeaux, Poitiers, Tours, and neighbourhood, and it is because of this

market that there has grown up at Arcachon such a considerable fishing

industry. The most picturesque part of the fishing industry carried on at

Arcachon is the night fishery. Whenever it becomes dark enough the

fishermen go out with the leister, and fish, as they used to do long ago

in the Tweed, from an illuminated boat. Three men are required for each

boat for the night fishing, two to row and one to hurl the spear. As many

as a dozen boats may be seen nightly at this work, each with a brilliant

flame of light flashing from its prow; the fish speared are mullet, and

they are mostly used for local consumption, the accession of visitors in

summer rendering a large supply of fish necessary. There are illuminated

fisheries in some other parts of France, but that of Arcachon is the most

prominent. The yield of fish, however, is not large-indeed it could not

be, when it is taken into account that each individual fish has to be

speared. Some more economical mode of night fishing, if night fishing be

necessary, ought to be invented. A few scores of mullet are a poor reward

for three or four hours' labour of three men.

The perpetual industry carried on by the coast people

on the French foreshores is quite a sight, although it is fish commerce of

a humble and primitive kind. Even the little children contrive to make

money by building fish-ponds, or erecting trenches, in which to gather

salt, or in some other little industry incidental to sea-shore life. One

occasionally encounters some abject creature groping about the rocks to

obtain the wherewithal to sustain existence. To these people all is fish

that comes to hand; no creature, however slimy, that creeps about is

allowed to escape, so long as it can be disguised by cookery into any kind

of food for human beings. Some of the people have old rickety boats

patched up with still older pieces of wood or leather, sails mended here

and there, till it is difficult to distinguish the original portion from

those that have been added to it; nets torn and darned till they are

scarce able to hold a fish; and yet that boat and that crippled machinery

are the stock in trade of perhaps two or three generations of a framily,

and the concern may have been founded half a century ago

by the grandfather, who now sees around him a legion of hungry

gamins that it would take a fleet of boats to keep in food and raiment.

The moment the tide flows back, the foreshore is at once overrun with an

army of hungry people, who are eager to clutch whatever fishy debris

the receding water may have left; the little pools are eagerly, nay

hungrily, explored, and their contents grabbed with that anxiety which

pertains only to poverty.

On some parts of the French coasts, and it is proper to

mention this, the fishery is not of importance, although fish are

plentiful enough. At Cancale, for instance, the fishermen have imposed on

themselves the restriction of only fishing twice a week. In Brittany, at

some of the fishing places, the people seem very poor and miserable, and

their boats look to be almost valueless, reminding one of the state of

matters at Fittie in the outskirts of Aberdeen. At the isle of Croix,

however, there is to be found a tolerably well-off maritime and fishing

community; at this place, where the men take to the sea at an early age,

there are about one hundred and thirty fishing boats of from twenty to

thirty tons each, of which the people - i.e. the practical fishermen-are

themselves the owners. At the Sands of Olonne there is a most extensive

sardine-fishery-the capture of sprats, young herrings, and young

pilchards, for curing as sardines, yielding a considerable share of

wealth, as a large number of boats follow this branch of business all the

year round. Experiments in artificial breeding are constantly being made

both with white fish and crustaceans, and sanguine hope,-, are entertained

that in a short time a plentiful supply of all kinds of shell and white

fish will reward the speculators, and as regards those parts of the French

coast which are at present destitute of the power of conveyance, the

apparition of a few locomotives will no doubt work wonders in instigating

a hearty fishing enterprise.

In fact the industry of the French as regards the

fisheries has become of late years quite wonderful, and there is evidently

more in their eager pursuit of sea wealth than all at once meets the eye.

No finer naval men need be wished for any country than those that are to

be found in the French fishing luggers, and there can be no doubt but that

they are being trained with a view to the more perfect manning of the

French navy. At any rate the French people (? government) have discovered

the art of growing sailors, and doubtless they will make the most of it,

being able apparently to grow them at a greatly cheaper rate than we can

do.

The commercial system established in France for

bringing the produce of the sea into the market is of a highly elaborate

and intricate character. The direct consequence of this system is, that

the price of fish goes on increasing from its first removal from the shore

until it reaches the market. This fact cannot be better illustrated than

by tracing the fish from the moment they are landed oil the quay by the

fishermen, through various intermediate transactions, until they reach the

hands of the fishmonger of Paris. The first agent into whose hands they

come is the ecoreur. The

ecoreur is

usually a qualified man appointed by the owners of the vessels, the

municipality, or by an association termed the Societe

d'Ecorage. He performs the functions of a wholesale agent

between the fishermen and the public. He is ready to take the fish out of

the fisherman's hands as soon as they are landed. He buys the fish from

the fisherman, and pays him at once, deducting a percentage for his own

services. This percentage is sometimes 5, 4, or even as low as 3 1/2 per

cent. He undertakes the whole risk of selling the fish, and suffers any

loss that may be incurred by bad debts or bad sale, for which he can make

no claim whatever upon the owner of the boat. The system of

ecorage is universally adopted, as the fisherman prefers

ready money with a deduction of 5 per cent rather than trouble himself

with any repayment or run the risk of bad debts. Passing from the

ecoreur we come to the

mareyeur -

that is, the merchant who buys the fish from the wholesale agent. He

provides baskets to hold the fish, packs them, and despatches them by

railway. He pays the carriage, the towndues or duties, and the fees to the

market-crier. Should the fish not keep, and arrive in Paris in bad

condition, and be complained of by the police, he sustains the loss. As

regards the transport arrangements, the fish are usually forwarded by the

fast trains, and the rates are invariable, whatever may be the quality of

the fish. Thus, turbot and salmon are carried at the same rate as monk

fish, oysters, and crabs. On the northern lines the rate is 37 cents per

ton per kilometre ; upon the Dieppe and Nantes lines, 25 or 26 cents ;

which gives 85 or 96 francs as the carriage of a ton of fish despatched

from the principal ports of the north-such as St. Valery-sur-Somme,

Boulogne, Calais, and Dunkerque - and 130 francs per ton on fish

despatched from Nantes.

The fish, on their arrival in Paris, are subjected to a

duty. For the collection of this duty the fish are divided into two

classes - viz, fine fresh fish and ordinary fresh fish. The fine

fish-which class includes salmon, trout, turbot, sturgeon, tunny, brill,

shad, mullet, roach, sole, lobster, shrimp, and oyster-pay a duty of 10

per cent of the market value. The duty upon the common fresh fish is 5 per

cent. This duty is paid after the sale, and is then of course duly entered

in the official register.

All fish sent to Paris are sold through the agency of

auctioneers (facteurs a la criee) appointed

by the town, who receive a commission of 2 or 3 per cent. The auctioneer

either sells to the fishmonger or to the consumer.

It will be seen from the above statement that between

the landing of the fish by the fisherman and the purchase of it by the

salesman at Paris there is added to the price paid to the fisherman 5 per

cent for the ecorage; 90, 100, or 130 francs

per ton for carriage ; 10 or 5 per cent, with a double tithe of war, for

town-dues ; and 3 per cent taken by the auctioneer-or, altogether, 18 or

13 per cent, besides the war -tithe and the cost of transport. This is an

estimate of the indispensable expenses only, and does not include a number

of items-such as the profit which the mareyeur

ought to make, the cost of the baskets, carriage from the market to

the railway, and from the custom-house to the market in Paris ; besides

presuming that the merchant who buys in the market is the consumer, which

is seldom the case.

The capture and cure of the sardine is a great business

in France, and especially at Concarneau, where as many as 13,000 men aid

in the fishery. It is not easy to obtain accurate statistics of the

business done in sardines. In the first place there is a large quantity

sold fresh-that is, packed in dry salt, in little baskets made of rushes,

and sent wherever there is a mode of outlet, Then there is an enormous

number sold in those familiar tins. It is said that besides the quantity

exported, which is large, there are as many as 4,000,000 boxes cured in

oil and prepared for the home market ; then, besides these, a large number

are sold in barrels, and also pressed in barrels. It is an interesting

sight to witness the arrival of the boats, and to see the rush to the

curing establishments of the men, women, and children interested in the

sales. How their sabots do clatter as they

prance over the stones ! The curers just buy from day to day what sardines

they require, and no more ; generally speaking, they do not, as in the

Scottish herring fishery, make contracts with boats, and only one or two

firms have boats of their own. When the curers are in want of a supply of

fish they put up a flag at their curing establishment, and the fishermen

hurry to supply them, the price varying from day to day according as the

fishery has been abundant or the reverse. As soon as the boats arrive the

fish are put in train for the cure, by being gutted, beheaded, sorted into

sizes, and washed in sea water, chiefly by women, who can earn from 12

francs to 20 francs a week at these curing establishments. The cure is

begun by drying the fish on nets or willows, generally in the open air,

but sometimes, from stress of weather it must be done under cover. After

being dried they are ready for the process of the pan, which is kept over

a furnace, and is filled with boiling oil. Into the cauldron the fish are

plunged, two rows deep, arranged on wire gratings. In this pan of oil (the

very finest olive oil) they remain for a brief period, till, in the

judgment of the cook, they are done sufficiently. Then they are placed to

drip, the drippings of oil being, of course, carefully collected ; after

which they are packed by women and girls into the nice little clean boxes

in which they are sold. Again they are allowed to drip by the boxes being

sloped ; then each box, by means of a tap, is filled carefully up to its

lip with pure olive oil, when it is ready for the next operation, which is

the soldering on of the lids, or, as it may be called, the hermetical

sealing up of the box, a most particular part of the process, at which the

men can earn very large wages, with this drawback, that they have to buy

all the fish that are spoilt. After the soldering has been accomplished

the boxes have to be boiled in a steam chest. Those that do not bulge out

after the boiling are condemned as " dead ;" for when the process is

thoroughly gone through the perfection of the cure is known by the bulging

out of the boxes, which are of various sizes, according to the purpose for

which they are designed. There are boxes of 6 lbs. weight and 21 lbs.

weight, as also half and quarter boxes, with from 24 to 12 fish in them,

according to size. Little kegs are also filled with sardines cured as

anchovies. The finishing process of the sardine cure is to stamp the boxes

and affix the thin brass labels which are always found upon them. There

are little incidental industries connected with the cure which may be

noticed. The debris is sold for agricultural purposes, as is the

case at home here, where the curers get a few pounds annually for their

offal ; then a large quantity of oil is exuded from the sprat during the

process of the cure, and on the total fishery this oil is of considerable

value. The " dead " fish, as we have said, are sold to the men, but the

success of the cure is usually so great that the "dead" form but a very

small percentage of the total number of boxes submitted to the test.

But allowing the French people to cultivate to the very

utmost-as they especially do as regards the oyster-it is impossible they

can ever exceed, either in productive power or money value, the fisheries

of our own coasts. If, without the trouble of taking a long journey, we

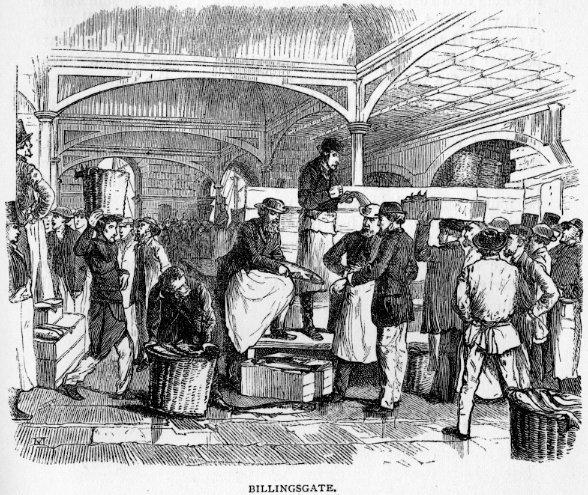

desire to witness the results of the British fisheries, we have only to

repair to Billingsgate to find this particular industry brought to a

focus. At that

piscatorial bourse we can see in the early morning the

produce of our most distant seas brought to our greatest seat of

population, sure of finding a ready and a profitable market. The

aldermanic turbot, the tempting sole, the gigantic codfish, the valuable

salmon, the cheap sprat, and the universal herring, are all to be found

during their different seasons in great plenty at Billingsgate; and in the

lower depths of the market buildings countless quantities of shell-fish of

all kinds, stored in immense tubs, may be seen; while away in the adjacent

lanes there are to be found gigantic boilers erected for the purpose of

crab and lobster boiling. Some of the shops in the neighbourhood have

always on hand large stocks of all kinds of dried fish,

which are carried away in great waggons to

the railway stations for country distribution. About four o’clock on a

summer morning this grand piscatorial mart may be seen in its full

excitement—the auctioneers bawling, the porters rushing madly about, the

hawkers also rushing madly about seeking persons to join them in buying a

lot, so as to divide their speculations; and all over is sprinkled the

dripping sea-water, and all around we feel that peculiar perfume which is

the concomitant of such a place. No statistics of a reliable kind are

published as to the value of the British fisheries. An annual account of

the Scottish herring-fishery is taken by commissioners and officers

appointed for that purpose; which, along with a yearly report of the Irish

fisheries, are the only reliable annual documents on the subject that we

possess, and the latest official report of the commissioners

will be found analysed in another part of this

volume. For any statistics of our white-fish fisheries we are compelled to

resort to second-hand sources of information; and, as is likely enough in

the circumstances, we do not, after all, get our curiosity properly

gratified on these important topics—the progress and produce of the

British fisheries.