Productive Power of Shell-Fish - Varieties of the Crustacean Family -

Study of the Minor Shell-Fishes - Demand for Shell-Fish - Lobsters - A

Lobster Store-Pond described - Natural History of the Lobster and other

Crustacea - March of the Land-Crabs - Prawns and Shrimps, how they are

caught and cured - A Mussel-Farm - How to grow bait.

SHELL-FISH is the popular name bestowed by unscientific

persons on the Crustacea and Mollusca, and no other designation could so

well cover the multitudinous variety of forms which are embraced in these

extensive divisions of the animal kingdom. Fanciful disquisitions on

shell-fish and on marine zoology have been intruded on the public of late

till they have become somewhat tiresome; but as our knowledge of the

natural history of all kinds of sea animals, and particularly of oysters,

lobsters, crabs, etc., is decidedly on the increase, there is yet room for

all that I have to say on the subject of these dainties; and there are

still unexplored wonders of animal life in the fathomless sea that deserve

the deepest study.

The economic and productive phases of our shell-fish

fisheries have never yet, in my opinion, been sufficiently discussed; and

when I state that the power of multiplication possessed by all kinds of

Crustacea and Mollusca is even greater, if that be possible, than that

possessed by finned fishes, it will be obvious that there is much in their

natural history that must prove interesting even to the most general

reader. Each oyster, as we have seen, gives birth to almost incredible

quantities of young. Lobsters also have an amazing fecundity, and yield an

immense number of eggs—each female producing from twelve to twenty

thousand in a season; and the crab is likewise most prolific. I lately

purchased a crab weighing within an ounce of two pounds, and it contained

a mass of minute eggs equal in size to a man's hand ; these were so minute

that a very small portion of them, picked off with the point of a pin,

when placed on a bit of glass, and counted by the aid of a powerful

miscroscope, numbered over sixty, each appearing of the size of a red

currant, and not at all unlike that fruit : so far as I could guess the

eggs were not nearly ripe. I also examined about the same time a quantity

of shrimp-eggs; and it is curious that, while there are the cock and lien

lobster, I never saw any difference in the sex of the shrimps : all that I

handled, amounting to hundreds, were females, and all of them were laden

with spawn, the eggs being so minute as to resemble grains of the finest

sand.

Although the crustacean family counts its varieties by

thousands, and contains members of all sizes, from minute animalculae to

gigantic American crabs and lobsters, and ranges from the simplest to the

most complex forms, yet the edible varieties are not at all numerous. The

largest of these are the lobster (Astacus marinus) and the crab

(Cancer pagurus) ; and river and sea cray-fish may also be seen in

considerable quantities in London shell-fish shops ; and as for common

shrimps (Crangon vulgaris) and prawns (Palaemon serratis),

they are eaten in myriads. The violet or marching crab of the West Indies,

and the robber crab common to the islands of the Pacific, are also

esteemed as great delicacies of the table, but are unknown in this country

except by reputation.

Leaving old and grave people to study the animal

economy of the larger Crustacea, the juveniles may with advantage take a

peep at the periwinkles, the whelks, or other Mollusca. These are found in

immense profusion on the little stones between high and low water mark,

and on almost every rock on the British coast. Although to the common

observer the oyster seems but a repulsive mass of blubber, and the

periwinkle a creature of the lowest possible organisation, nothing can be

farther from the reality. There is throughout this class of animals a

wonderful adaptability of means to ends. The turbinated shell of the

periwinkle, with its finely-closed door, gives no token of the powers

bestowed upon the animal, both as provision for locomotion (this class of

travellers wherever they go they carry their house along with them) and

for reaping the tender rock-grass upon which they feed. They have eyes in

their horns, and their sense of vision is quick. Their

curiously-constructed foot enables them to progress in any direction they

please, and their wonderful tongue either acts as a screw or a saw. In

fact, simple as the organisation of these animals appears to be, it is not

less curious in its own way than the structure of other beings which are

thought to be more complicated. In good truth, the common periwinkle (Littorina

vulgaris) is both worth studying and eating, vulgar as some people may

think it.

Immense quantities of all the edible molluscs are

annually collected by women and children in order to supply the large

inland cities. Great sacks full of periwinkles, whelks, etc., are sent on

by railway to Manchester, Glasgow, London, etc. ; whilst on portions of

the Scottish sea-coast the larger kinds are assiduously collected by the

fishermen's wives and prepared as bait for the long hand-lines which are

used in capturing the codfish or other Gadidae. As an evidence of how

abundant the sea-harvest is, I may mention that from a spot so far north

as Orkney hundreds of bags of periwinkles are weekly sent to London by the

Aberdeen steamer.

From personal inquiry made by the writer he estimated

that for the commissariat of London alone there were required three

millions of crabs and lobsters ! May we not, therefore, take for granted

that the other populous towns of the British empire will consume an

equally large number ? The people of Liverpool, Manchester, Edinburgh,

Glasgow, and Dublin, are as fond of shell-fish as the denizens of the

great metropolis; at any rate, they eat all they can get, and never get

enough. The machinery for supplying this ever-increasing demand for

lobsters, crabs, and oysters, is exceedingly simple. On most parts of the

British coast there are people who make it their business to provide those

luxuries of the table for all who wish them. The capital required for this

branch of the fisheries is not large, and the fishermen and their families

attend to the capture of the crab and lobster in the intervals of other

business. The Scotch laird's advice to his son to "be always stickin' in

the ither tree, it will be growin' when ye are sleepin'," holds good in

lobster-fishing. The pots may be baited and left till such time as the

victim enters, whilst the men in the meantime take a short cruise in

search of bait, or try a cast of their haddock-lines a mile or two from

the shore ; or the fishing can be watched over, and when the lobsters are

numerous, the pots be lifted every half-hour or so. The taking of

shell-fish also affords occupation to the old men and youngsters of the

fishing villages, and these folks may be seen in the fine days assiduously

waiting on the lobster-traps and crab-cages, which are not unlike

overgrown rat-traps, and are constructed of netting fastened over a wooden

framework, baited with any kind of fish offal, or garbage, the stench of

which may be strong enough to attract the attention of those minor

monsters of the deep. A great number of these lobster-pots are sunk at,

perhaps, a depth of twelve or twenty fathoms at an appropriate place,

being held together by a strong line, and all marked with a peculiarly-cut

piece of cork, so that each fisherman may recognise his own lot. The

knowing youngsters of our fishing communities can also secure their prey

by using a long stick. Mr. Cancer Pagurus is watched as he bustles out for

his evening promenade, and, on being deftly pitched upon his back by means

of a pole, he indignantly seizes upon it with all his might, and the stick

being shaken a little has the desirable effect of causing Mr. Crab to

cling thereto with great tenacity, which is, of course, the very thing

desired by the grinning "human" at the other end, as whenever lie feels

his prey secure lie dexterously hauls him on board, unhooks the crusty

gentleman with a jerk, and adds him to the accumulating heap at the bottom

of the old boat. The monkeys in the West Indies are, however, still more

ingenious than the "fisher loons" of Arran or Skye. Those wise animals,

when they take a notion of dining on a crab, proceed to the rocks, and

slyly insinuating their tail into one of the holes where the crustacea

take refuge, that appendage is at once seized upon by the crab, who is

thereby drawn from his hiding-place, and, being speedily dashed to pieces

on the hard stone, affords a fine feast to his captor. This reminds me of

the story told about a man's dog which was seized by a crab when passing a

fish shop : Punch has it, "Whustle on your dog, man;" "Na, na, my

man; whustle you on your partan." On the granitebound coast of Scotland

the sport of crab-hunting may be enjoyed to perfection, and the wonders of

the deep be studied at the same time. A long pole with a small crook at

the end will be found useful to draw the crab from his nest, or great fun

may be enjoyed by tying during low-water a piece of bait to a string and

attaching a stone to the other end of the cord. The crab seizes upon this

bait whenever the tide flows, and drags it to its hole, so that when the

ebb of the tide recurs, the stone at the end of the cord marks the

hiding-place of the animal, who thus falls an easy prey to his captor. The

natives are the best instructors in these arts, and seaside visitors

cannot do better than engage the services of some strong fisher youth to

act as guide in such perambulations as they may make on the beach. There

are few seaside places where the natives cannot guide strangers to rock

pools and picturesque nooks teeming with materials for studying the

wonders of the shore.

Lobsters are collected and sent to London from all

parts of the Scottish shore. I have seen on the Sutherland and other

coasts perforated floating chests filled with them. They were kept till

called for by the welled smacks, which generally make the circuit of the

coasts once a week, taking up all the lobsters or crabs they can get, and

carrying them alive to London. From the Durness shores alone as many as

from six to eight thousand lobsters have been collected in the course of a

single summer, and sold, big or little, at threepence each to the buyers.

The lobsters taken on the north-east coast of Scotland and at Orkney are

now packed in seaweed and sent in boxes to London by railway. Lobsters

have not been so plentiful, it is thought, in the Orkney Islands of late

years; but a large trade has been done in them since the railway was

opened from Aberdeen-at all events, the prices of lobsters are double what

they used to be in the time of the welled smacks alluded to above. The

fisher-folks of Orkney confess that the trade in lobsters pays them well.

At some places in Scotland lobsterfishing is pursued at great risk. Among

the groups of rocky islands on the west coast of Scotland, it is often a

work of great danger to set the lobster-pots, and often enough after being

set they cannot again be reached, in consequence of sudden squalls, till

many days have elapsed ; so that, if the remuneration for the labour is

good, it is sometimes very hardly earned.

All kinds of crustaceans can be kept alive at the place

of capture till " wanted "-that is, till the welled vessel which carries

them to London or Liverpool arrives-by simply storing them in a large

perforated wooden box anchored in a convenient place. Nor must it be

supposed that the acute London dealers allow too many lobsters to be

brought to market at once; the supply is governed by the demand, and the

stock kept in large store-boxes at convenient places down the river, where

the sea-water is strong and the liquid filth of London harmless. But these

old-fashioned store-boxes will, no doubt, be speedily superseded by the

construction of artificial store-ponds on a large scale, similar to that

erected by Mr. Richard Scovell at Hamble, near Southampton. That

gentleman's pond has been of good service to him. It is about fifty yards

square, and is lined with brick, having a bottom of concrete, and was

excavated at a cost of about £1200. It will store with great ease 50,000

lobsters, and the animals may remain in the pond as long as six weeks,

with little chance of being damaged. Lobsters, however, do not breed in

this state of confinement, nor have they been seen to undergo a change of

shell. There is, of course, an apparatus of pipes and sluices for the

purpose of supplying the pond with water. The stock is recruited from the

coasts of France and Ireland ; and to keep up the supply Mr. Scovell has

in his service two or three vessels of considerable size, which visit the

various fisheries and bring the lobsters to Hamble in their capacious

wells, each of which is large enough to contain from 5000 to 10,000

animals.

The west and north-west coasts of Ireland abound with

fine lobsters, and welled vessels bring thence supplies for the London

market, and it is said that a supply of 10,000 a week can easily be

obtained. Immense quantities are also procured on the west coast of

Scotland. A year or two ago I saw on board the Islesman steamboat

at Greenock a cargo of 30,000 lobsters, obtained chiefly on the coasts of

Lewis and Skye. The value of these to the captors would be upwards of

£1000, and in the English fishmarkets the lot would bring at least four

times that sum.

A very large share of our lobsters is derived from

Norway, as many as 30,000 sometimes arriving from the fjords in a single

day. The Norway lobsters are much esteemed, and we pay the Norwegians

something like £20,000 a year for this one article of commerce.

They are brought over in welled steam-vessels, and are kept in the wooden

reservoirs already alluded to, some of which may be seen at Hole Haven, on

the Essex side of the Thames. Once upon a time, some forty years ago, one

of these wooden lobster-stores was run into by a Russian frigate, whereby

some 20,000 lobsters were set adrift to sprawl in the muddy waters of the

Thames. In order that the great mass of animals confined in these places

may be kept upon their best behaviour, a species of cruelty has to be

perpetrated to prevent their tearing each other to pieces; the great claw

is there rendered paralytic by means of a wooden peg being driven into a

lower joint.

I have no intention of describing the whole members of

the crustacea; they are much too numerous to admit of that, rang-inn as

they do from the comparatively giant-like crab and lobster down to the

millions of minute insects which at some places confer a phosphorescent

appearance on the waters of the sea. My limits will necessarily confine me

to a few of the principal members of the family-the edible crustacea, in

fact; and these I shall endeavour to speak about in such plain language as

I think my readers will understand, leaving out as much of the fashionable

"scientific slang" as I possibly can.

The more we study the varied crustacea of the British

shores, the more we are struck with their wonderful formation, and the

peculiar habits of their members. I once heard a clergyman at a lecture

describe a lobster in brief but fitting terms as a standing romance of the

sea-an animal whose clothing is a shell, which it casts away once a year

in order that it may put on a larger suit-an animal whose flesh is in its

tail and legs, and whose hair is in the inside of its breast, whose

stomach is in its head, and which is changed every year for a new one, and

which new one begins its life by devouring the old ! an animal which

carries its eggs within its body till they become fruitful, and then

carries them outwardly under its tail; an animal which can throw off its

legs when they become troublesome, and can in a brief time replace them

with others ; and lastly, an animal with very sharp eyes placed in movable

horns. The picture is not at all overdrawn. It is a wondrous creature this

lobster, and I may be allowed a brief space in which to describe the

curious provision of nature which allows for an increase of growth, or

provides for the renewal of a broken limb, and which applies generally to

the edible crustacea.

The habits of the principal crustacea are not pretty

well understood, and their mode of growth is so peculiar as to render a

close inspection of their habits a most interesting study. As has been

stated, a good-sized lobster will yield about 20,000 eggs, and these are

hatched, being so nearly ripe before they are abandoned by the mother,

with great rapidity-it is said in forty-eight hours-and grow quickly,

although the young lobster passes through many changes before it is fit to

be presented at table. During the early periods of growth it casts its

shell frequently. This wonderful provision for an increase of size in the

lobster has been minutely studied during its period of moulting. Mr.

Jonathan Couch says the additional size which is gained at each period of

exuviation is perfectly surprising, and it is wonderful to see the

complete covering of the animal cast off like a suit of old clothes, while

it hides, naked and soft, in a convenient hole, awaiting the growth of its

new crust. In fact, it is difficult to believe that the great soft animal

ever inhabited the cast-off habitation which is lying beside it, because

the lobster looks, and really is, so much larger. The lobster, crab, etc.,

change their shells about every six weeks during the first year of their

age, every two months during the second year, and then the changing of the

shell becomes less frequent, being reduced to four times a year. It is

supposed that this animal becomes reproductive at the age of five years.

In France the lobster-fishery is to some extent " regulated." A close-time

exists, and size is the one element of capture that is most studied. All

the small lobsters are thrown back to the water. There is no difficulty in

observing the process of exuviation. A friend of mine had a crab which

moulted in a small crystal basin. I presume that at some period in the

life of the crab or lobster growth will cease, and the annual moulting

become unnecessary ; at any rate, I have seen crabs and other crustaceans

taken from an island in the Firth of Forth which •

were covered with parasites evidently two or three years old.

To describe minutely the exuviation of a lobster, crab,

or shrimp, would in itself form an interesting chapter of this work, and

it is only of late years that many points of the process have been

witnessed and for the first time described. Not long ago, for instance, it

was doubtful whether or not the hermit-crabs (Anonaoura)

shed their skin ; and, that fact being settled, it became a question

whether they shed the skin of their tail ! There was a considerable amount

of controversy on this delicate point, till the "strange and unexpected

discovery "was made by Mr. Harper. That gentleman was fortunate enough to

catch a hermit-crab in the very act, and was able to secure the caudal

appendage which had just been thrown off. Other matters of controversy

have been instituted in reference to the growth of various members of the

crustacea; indeed, the young of the crab in an early stage have before now

been described by naturalists as distinct species, so great is the

metamorphosis they undergo before they assume their final shape-just as

the sprat in good time changes in all probability to the herring.

Another point of controversy at one period existed in

reference to the power of crustaceans to replace their broken limbs, or

occasionally to dispense, at their own good pleasure, with a limb, when it

is out of order, with the absolute certainty of replacing it.

When the female crustacea retire in order to undergo

their exuviation, they are watched, or rather guarded, by the males; and

if one male be taken away, in a short time another will be found to have

taken his place. I do not think there is any particular season for

moulting ; the period differs in different places, according to the

temperature of the water and other circumstances, so that we might have

shell-fish (and white-fish too) all the year round were a little attention

paid to the different seasons of exuviation and egg-laying.

The mode in which a hen lobster lays her eggs is

curious: she lodges a quantity of them under her tail, and bears them

about for a considerable period; indeed, till they are so nearly hatched

as only to require a very brief time to mature them. When the eggs are

first exuded from the ovary they are very small, but before they are

committed to the sand or water they increase considerably in size,

and become as large as good-sized shot. Lobsters may be found with eggs,

or "in berry" as it is called, all the year round ; and when the hen is in

process of depositing her eggs she is not good for food, the flesh being

poor, watery, and destitute of flavour.

When the British crustacea are in their soft state they

are not considered as being good for food ; but, curiously enough, the

land-crabs are most esteemed while in that condition. The epicure who has

not tasted "soft crabs" should hasten to make himself acquainted with one

of the most delicious luxuries of the table. The eccentric land-crab,

which lives far inland among the rocks, or in the clefts of trees, or

burrows in holes in the earth, makes in the spring-time an annual

pilgrimage to the sea in order to deposit its spawn, and the young, guided

by an unerring instinct, return to the land in order to live in the rocks

or burrow in the earth like their progenitors. In the fish-world we have

something nearly akin to this. We have the salmon, that spends one-half

its life in the sea, and the other half in the fresh water ; it proceeds

to the sea to attain size and strength, and returns to the river in order

to perpetuate its kind. The eel, again, just does the reverse of all this;

it goes down to the sea to spawn, and then proceeds up the river to live;

and at certain seasons it may be seen in myriad quantities making its way

up stream. The march of the land-crabs is a singular and interesting

sight: they congregate into one great army, and travel in two or three

divisions, generally by night, to the sea ; they proceed straight forward,

and seldom deviate from their path unless to avoid crossing a river. These

marching crabs eat up all the luxuriant vegetation on their route ; their

path is marked by desolation. The moment they arrive at the water the

operation of spawning is commenced by allowing the waves to wash gently

over their bodies. A few days of this kind of bathing assists the process

of oviposition, and knots of spawn similar to lumps of herring-roe are

gradually washed into the water, which in a short time finishes the

operation. Countless thousands of these eggs are annually devoured by

various fishes and monsters of the deep that lie in wait for them during

the spawning season. After their brief seaside sojourn, the old crabs

undergo their moult, and at this period thousands of them sicken and die,

and large numbers of them are captured for table use, soft crabs being

highly esteemed by all lovers of good things. By the time they have

recovered from their moult the army of juveniles from the seaside begins

to make its appearance in order to join the old stock in the mountains;

and thus the legion of land-crabs is annually recruited by a fresh batch,

which in their turn perform the annual migration to the sea much as their

parents have done before them.

It is worth noting here that lobsters are year by year

becoming "smaller by degrees and beautifully less," all the large ones are

being fished up and the small ones are never allowed to become bigger in

consequence of the yearly increasing demands of the public. As a general

rule, the great bulk of lobsters are not much more than half the size they

used to be. The remedy is a close-time. Yes; there must be a close-time

instituted for the lobster and the crab as well.

Before leaving the crabs and lobsters, it is worthy of

remark that an experienced dealer can tell at once the locality whence any

particular lobster is obtained-whether from the west of Ireland, the

Orkney Islands, or the coast of Brittany. The shelly inhabitants of

different localities are distinctly marked. Indeed fish are peculiarly

local in their habits, although the vulgar idea has hitherto been that all

kinds of sea animals herd indiscriminately together; that the crab and the

lobster crept about the bottom rocks, whilst the waving skate or the

swaggering ling fish dashed about in mid-water, the prowling "dogs" busily

preying on the shoals of herring supposed to be swimming near; the

brilliant shrimp flashing through the crowd like a meteor, the elegant

saithe keeping them company; the whole being overshadowed by a few whales,

and kept in awe by a dozen or so of sharks ! Nothing can be more different

than the reality of the water-world, which is colonised quite as

systematically as the earth. Particular shoals of herring, for instance,

gather off particular counties ; the Lochfyne herring, as I have mentioned

in the account of the herring-fishery, differs from the herring of the

Caithness coast or that of the Firth of Forth ; and any 'cute fishmonger

can tell a Tweed salmon from a Tay one. The herring at certain periods

gather in gigantic shoals, the chief members of the Gadidae congregate on

vast sand-banks, and the whales occasionally roam about in schools ; while

the Pleuronectidae occupy sandy places in the bottom of the sea. We have

all heard of the great cod-banks of Newfoundland, of the fish community at

Rockall; then is there not the Nymph Bank, near Dublin, celebrated for its

haddocks ? have we not also the Faroe fishing -ground, the Dogger Bank,

and other places with a numerous fish population? There are wonderful

diversities of life in the bosom of the deep ; and there is beautiful

scenery of hill and plain, vegetable and rock, and mountain and valley.

There are shallows and depths suited to different aspects of life, and

there is life of all kinds teeming in that mighty world of waters, and the

fishes live

"A cold sweet silver life, wrapped in round waves,

Quickened with touches of transporting fear."

The prawn and the shrimp are ploughed in innumerable

quantities from the shallow waters that lave the shore. The shrimper may

be seen any day at work, pushing his little net before him. To reach the

more distant sandbanks he requires a boat ; but on these he captures his

prey with greater facility, and richer hauls rewards his labour than when

he plies his putting-net close inshore. The shrimper, when he captures a

sufficient quantity, proceeds to boil them ; and till they undergo that

process they are not edible. The shrimp is "the 'Undine' of the waters,"

and seems possessed by some aquatic devil, it darts about with such

intense velocity. Like the lobster and the crab, the prawn periodically

changes its skin ; and its exertions to throw off its old clothes are

really as wonderful as those of its larger relatives of the lobster and

crab family. There are a great many species of shrimp in addition to the

common one ; as, for instance, banded, spinous, sculptured, three-spined,

and two-spined. Young prawns, too, are often taken in the "puttingnets "

and sold for shrimps. Prawns are caught in some places in pots resembling

those used for the taking of lobsters. The prawn exuviates very frequently

; in fact, it has no sooner recovered from one illness than it has to

undergo another. Although the prawn and the shrimp are exceedingly common

on the British coasts, when we consider the millions of these "sea

insects," as they have been called, which are annually consumed at the

breakfast tables and in the tea-gardens of London alone (not to speak of

those which are greedily devoured in our watering-places, or the few which

are allowed to reach the more inland towns of the country), we cannot but

wonder where they all come from, or who provides them ; and the problem

can only be solved by taking into account the fact that we are surrounded

by hundreds of miles of a productive seaboard, and that thousands of

seafaring people, and others as well, make it their business to supply

such luxuries to all who can pay for them. It is even found profitable to

send these delicacies to England all the way from the remote fisheries of

Scotland.

The art of "shrimping" is well understood all round the

English coasts. The mode of capturing this particular member of the

crustacea is by what is called a shrimp-net, formed of a frame of wood and

twine into a long bag, which is used as a kind of miniature trawl-net ;

each shrimping-boat being provided with one or two of these instruments,

which, scraping along the sand, compel the shrimp to enter. Each boat is

provided with a "well," or store, to contain the proceeds of the nets, and

on arrival at home the shrimps are immediately boiled for the London or

other markets. The shrimpers are rather ill-used by the trade. Of the many

thousand gallons ,cut daily to London, they only get an infinitesimal

portion of the money produce. The retail price in London is four shillings

per gallon, out of which the producer is understood to get only threepence

! I have been told that the railways charge at the extraordinary rate of

£9 a ton for the carriage of this delicacy to London. It is an interesting

sight to watch the shrimpers at their work, and such of my readers as can

obtain a brief holiday should run down to Leigh, or some nearer fishing

place, where they can see the art of shrimping carried on in all its

picturesque beauty.

The fresh-water cray-fish, a very delicate kind of

miniature lobster, abundantly numerous in all our larger streams, and

exceedingly plentiful in France, may often be seen on the counters of our

fishmongers ; as also the sea cray-fish, which is much larger in size,

having been known to attain the weight of ten or twelve pounds, but it is

coarser in the flavour than either the crab or lobster. The river cray-fish,

which lodges in holes in the banks of our streams, is caught simply by

means of a split stick with a bit of bait inserted at the end. The

fresh-water cray-fish has afforded a better opportunity for studying the

structure of the crustacea than any of the saltwater species, as its

habits can be more easily observed. The sea cray-fish is not at all

plentiful in the British Islands, although we have a limited supply in

some of our markets.

There has hitherto been a fixed period for the annual

sacrifice to crustacean gastronomy. As my readers are already aware, there

is a well-known time for the supplying of oysters, which is fixed by law,

and which begins in August and ends in April. During the r-less months

oysters are less wholesome than in the colder weather. The season for

lobsters begins about March, and is supposed to close with September, so

that in the round of the year we have always some kind of shell-fish

delicacy to feast upon. Were a little more attention devoted to the

economy of our fisheries, we might have lobsters and crabs upon our tables

all the year round. In my opinion lobsters are as good for food in the

winter time as during the months in which they are most in demand. It may

be hoped that we shall get to understand all this much better by and by,

for at present we are sadly ignorant of the natural economy of these, and

indeed all other denizens of the deep.

Considering the importance attached by fishermen to the

easy attainment of a cheap supply of bait, it is surprising that no

attempt has been made in this country to economise and regulate the

various mussel-beds which abound on the Scottish and English coasts. The

mussel is very largely used for bait, and fishermen have to go far, and

pay dear, for what they require -their wives and families being also

employed to gather as many as they can possibly procure on the accessible

places of the coast, but usually the bait has to be purchased and carried

from long distances. I propose to show our fisher-people how these matters

are managed in France, and how they may obviate the labour and expense

connected with bait buying or gathering, by growing such a crop of mussels

as would not only suffice for an abundant supply of bait, but produce a

large quantity for sale as well.

It is no exaggeration to say that, although the British

people are shy of eating the mussel, except when it is cooked for sauce -

and a very excellent sauce it makes - countless millions are annually

required by our fishermen for bait. There is one little fishing-village in

Scotland which I know, from personal investigation, uses for its own

share, for the baiting of the deep-sea lines required in the cod and

haddock fishery, close on five millions of these molluscs, which have all

to be sought and gathered from the natural beds, the men, and the women as

well, having frequently to go long distances to obtain them. These figures

will not be thought to be exaggerated when I say that each deep-sea line

requires about twelve hundred mussels to bait it; and as many of the boats

carry eight or ten lines, it is easy to check the calculation. The

fishermen, it is hoped, may by and by come to grow their own

mussels, as do the industrious men of Aiguillon; and if they do not turn

mussel-farmers after what I have to tell them, they will have themselves

to blame for the ultimate extinction of the mussel, for the natural scalps

are giving way under the present increasing demand for bait.

"Where is Aiguillon?" was naturally enough the first

question I had to answer, after determining to visit the great French

mussel-farm ; but no one could answer it. I asked many who are interested

in fishery matters, but none of them had heard of the mussel-farm.

Aiguillon, they said, was mentioned in Murray's Guide, and doubtless the

site of the fishery would be there. But the mussel-farm is not at the

Aiguillon mentioned by Murray, which is a town, of nearly two thousand

inhabitants, on the left bank of the Lot, about a mile above its influx

into the Garonne. My Aiguillon, indeed, is not even on the same line of

railway, although it is at an equally great distance from Pall Mall. In

fact, Murray contains nothing at all about my Aiguillon. Murray has a soul

above mussels, and, to speak the truth, doesn't even seem to care much

about oysters, seeing that he sometimes neglects to mention localities

where they are grown in the greatest profusion. I found my Aiguillon at

the port of Esnandes, which is itself a curious out-of-the-way place.

In order to see the mussel-farm, it is necessary first

to get to Paris, and to take the Orleans Railway to Poitiers, then to

change to the line for La Rochelle, after reaching which place a

voiture must be hired for the rest of the journey, Esnandes being

about seven kilometres from Rochelle. I need not weary the reader with a

description of all that is to be seen on the Orleans Railway, which, as

all the travelling world at least knows, runs through the most historical

part of France. Looking from the window of the railway carriage, I enjoyed

for a few hours the lovely champaign scenery of the claret district of

France. There are vine-fields, and big joint-stock walnut trees, and

cherry orchards-and cherry orchards, walnut trees, and vineyards, over and

over again, all the way to Bordeaux. Then there are little patches of

water ; and dark-green grassy quadrangles laid down every here and there,

guarded by those tall alder trees one sees in such profusion all over the

Continent. Every here and there, too, may be seen a distant chateau on its

finely-wooded hill ; then come a few old farmhouses, their inner yards

alive with the minute industry of the plodding husbandmen. Anon we pass

the outskirts of old historical towns, tempting one to break one's

journey.

It might have well suited others to perform these

pleasures of travel; my errand was to see la moule. History had no

charms for me till I had seen the mussel-farms, which I had come so far to

visit. To my exceeding astonishment, almost no one in La Rochelle knew

anything about the industry of Aiguillon. I had to search far and wide to

obtain information as to how to get to the place ; another exemplification

of the old story, that one may live all his life in London, and not be

able to find his way to St. Paul's. By virtue of a little Scottish

perseverance, and the expenditure of much bad French, I at length found

out that it was at Esnandes that they cultivated la moule. So,

procuring a voiture, and a garcon to drive it, I sallied away out

through the gates and barriers of La Rochelle ; and after a pleasant drive

through the vineyards and small farms of the district, on each of which

there appeared to be a little flock of black sheep, I arrived in about an

hour's time at my destination, much to the astonishment of the idle

poultry and young dogs of the neighbourhood, which looked and acted as if

they never had seen a voiture or a Scotchman before.

The port of Esnandes is very much like all other fish'

villages, and the fisher-people like all other fishing-people. As you

enter the town, you feel that it has the usual ancient and fish-like

smell; and you see, as you suppose, the same little boys with the

overgrown small-clothes that you meet with in the fishing-villages of

England or Scotland. After passing a little way down the one street of the

village, you observe all the way, right and left, the invariable mussel

middens, the worn-out old fish-baskets, and the various other insignia of

the trade of the people, the like of which you can also see at Whitstable

or Cockenzie. The people waken up the moment it is buzzed about that a

stranger has arrived. At first, I thought the population were all out at

sea, but I was so quickly surrounded by an inquisitive little crowd, that

I speedily gave up that idea; and as soon as I had explained my errand to

the buxom landlady of the village cafe, I was provided with a guide, who

kindly escorted me to the bouchots (fishing hurdles), or rather to

the depot of the boucholiers, which is about a quarter of a mile from the

village.

Having alighted from the carriage, I looked around me

with some curiosity ; but I saw no farm of mussels, no appearance even of

there being a common fishery. About a mile away to the right there was

moored a small fleet of the common flatbottomed fishery-boats peculiar to

the coast. A few miles to the left lay the Ile de Rd, famous for its

oyster-beds; but where was the object of my search-the mussel-farm ? Well,

to make a long story short, the farm was at that particular hour covered

with water; but, as the tide was on the ebb, I speedily obtained a view of

the vast mud-fields to which the people of Esnandes are indebted for their

peculiar fish-commerce. The story of the translation of these vast sloughs

of mud into fertile fields of industry, productive of comfort and wealth,

is short and simple, for the discovery of the bouchot was purely

accidental. An Irish vessel, laden with sheep, having been wrecked in the

bay, so long ago as the year 1235, only one out of all the crew was saved.

This man's name was Walton, and he became the founder of the present

industry by means of the bouchot system of cultivation. On finding himself

saved, he at once set about finding a means of earning his own food, so

that he might not be a burden upon the poor fishermen who had rescued him

from the ravening waters, and who were themselves at the time wellnigh

destitute of every comfort of life.

All around him, however, as Walton soon perceived, was

one vast expanse of liquid mud, and what could any man do on such a barren

field? Walton speedily solved the problem. He first of all invented a mode

of travelling upon the mud-bed, for walking was an impossibility, as at

every step he sank up to the knees in the miry clay. This boat is called

a pirogue by the boucholiers, and it is still in use. By means of

this simple machine, which I will by and by describe, Walton was able to

travel along and explore the muddy coast, by which he found out that vast

numbers of land and sea birds used to assemble on the waters and in the

mud in search of food. A kind of purse-net for the capture of these birds

at once suggested itself to the hungry sailor. This being made and set on

the mud as a trap to float with the tide, was found to answer admirably,

and every night large numbers of aquatic birds were captured in its

purse-like folds. It was out of that little example of a destitute

sailor's ingenuity that the present industry of Aiguillon was developed,

for it was not long before Walton found the strong posts to which he had

affixed his net all covered over with the spawn of the edible mussel ;

these he found grew very rapidly, and when mature, had a much finer

flavour than the mud-grown bivalves from whence the spawn had floated. The

Irishman soon saw how he could multiply his own food-supplies, and create

at the same time a lasting industry for the benefit of the poor people

among whom he had been thrown by his unfortunate shipwreck; he therefore

went on multiplying his stakes, till he found that there was no end to the

produce; so that in due time this accidental discovery became a rich

inheritance to the fisher-folks of the district, for in ten years after

the shipwreck the bay was covered with an appropriate and successful

mussel-collecting apparatus, out of which has grown the present extensive

commerce.

The work of cultivation at Aiguillon is carried on very

systematically. I shall give what I learned about it, just as I saw it

myself, or as it was described to me by my guide, a very civil and

`immensely voluble fisherman, who had the whole theory and practice of

mussel-farming at his finger-ends, or rather at the end of his tongue. It

was truly curious to consider that the same mode of cultivating and

working was going on that had prevailed from the beginning-the invention

having been perfect from the first. One of the most curious phases of the

whole industry is the mode of progression over the fields which has been

adopted by the men, for each man has not only to paddle his own canoe on

these soft fields of mud, but if he have a visitor, he has to paddle his

boat as well. The manner of progression is very primitive. The man kneels

in his little wooden vessel with one leg, the other, being encased in a

great boot, is fixed deep in the mud ; a lift of the little canoe with

both hands, and a simultaneous shove with the mud-engulfed leg, and lo ! a

progress of many inches is achieved ; this action, frequently repeated by

the industrious labourers, soon overcomes the distance between the

different fields ; and when a new trousseau has to be carried out

to the bouchots, or a stranger has to be conducted over the fields, two

men will load a canoe, and work it out between them, not, however, without

a few jolts and jerks, which, like a ride on a camel's back, is rather

tiring to the unaccustomed. When three of the canoes are joined together

by means of pieces of stout rope, the boucholier in the first one uses his

left leg as the propelling power, while the man in No. 3 uses his right

leg, and by this means they get along in a straighter line and with

greater speed. This peculiar boatexercise has not a little of the comic

element in it, especially when one sees a fleet of more than a hundred

narrow boats all propelled in the same eccentric manner by upwards of one

hundred merry boucholiers. I may mention that the mud at Aiguillon is

unusually smooth and soft ; there are no sun-baked furrows to interrupt

the progress of the canoe, a fact that is due to the presence of a little

animal, which accomplishes for the boucholier what a regiment of a

thousand soldiers could not perform.

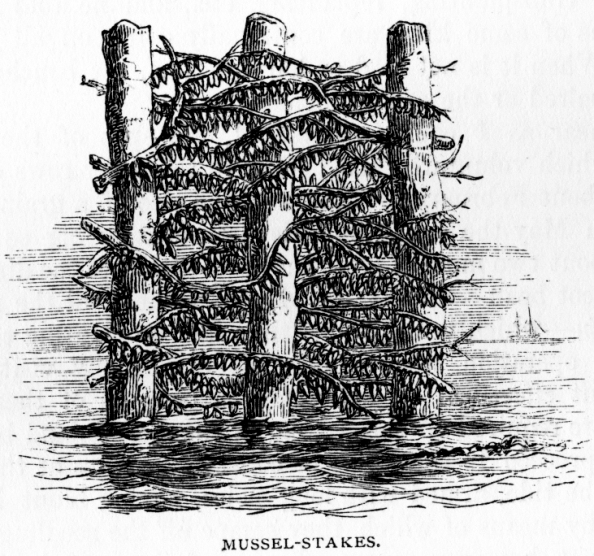

In addition to the large and strong stakes originally

used as holdfasts for his bird-nets, Walton planted others, in long rows,

in the form of a double V, with their apex open to the sea, the sides

being interlaced with branches of trees, to which the mussels, by means of

their byssus, affixed themselves with great aptitude. These bouchots were

also so arranged one with another so as to serve as traps for the taking

of such fish and crustaceans as frequent the coast; so that the fishermen

had thus a double chance, being, of course, always assured, when there is

no fish, of a canoeful of mussels.

The men in search of fish depart for the farm a little

time before the tide recedes, and taking their places at the mouth or apex

of the V, they affix a small net to the opening, so that they are sure to

intercept any fish that may have come in to feed with the previous tide. I

made very particular inquiries into the constitution of the farm, and

although disappointed at not finding it, as I was led to expect, a vast

scene of perfect co-operation, I was pleased to learn that, although the

bouchots had many owners, there was no violent competition among those who

owned them. Some of these mussel-farmers have three or four bouchots, and

the very poorest among them have a half, or at least a third share in one.

The system of family co-operation prevails very largely ; I found, as in

the case of the celebrated walnut-trees, so often quoted, that one or two

families, grandfathers, sons, and grandchildren, were often the owners of

several bouchots, which they worked for their joint benefit, dividing the

profits at the end of the season.

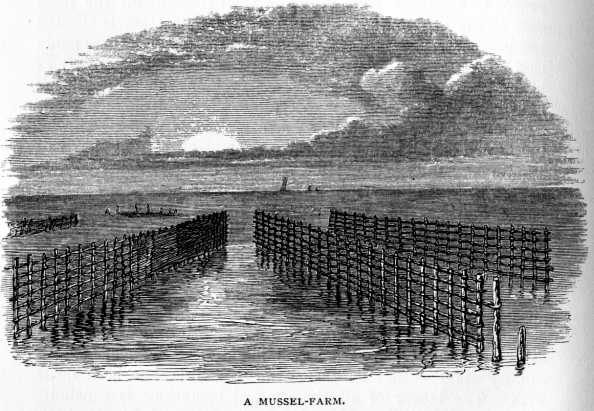

The farm occupies a very large space of ground, equal

to eight kilometres, and is laid out in four fields or divisions, each of

which has its peculiar name and use. There are at least 500

bouchots, and each one represents a length of 450

metres, forming a total wall of strong basket-work, all for the growth of

mussels, equal to a length of 225,000 metres, and rising six feet above

the mud-bed on which it is erected.

Great pains are taken to keep the bouchots in good

order ; repairs are continually being made; and along the protecting wall

of the cliff by which the bay is bounded, there are to be seen what my

guide called the trousseau of the bouchots - great strong wooden stakes

twelve feet long, and of considerable girth. These are sunk into the mud

to a depth of six feet, the upper portion being the receptacle of a

garniture of strong but supple branches, twisted in the form of basket

work, on which are grown the annual crops of mussels. The bouchots have

different names, according to their uses and their situation. The

bouchots du bas are those farthest away in

the water : these are very seldom left uncovered by the tide; they are

formed of very large and very strong solitary stakes, planted so near each

other that there are three of them to each metre.

The duty of these stakes is to enact the part of

spat-collectors -the spat is locally called naissain

at the Port of Esnandes -so that there may be always a store of

infant mussels for the peopling and repeopling of such of the palisades as

may accidentally become barren. My guide, in describing to me the

operations of the farm, used agricultural terms, such as seeding,

planting, transplanting, replanting, etc., and he told me that operations

of some kind are continually going on all over the farm. When it is not

seed or harvest time, the bouchots have to be repaired or the canoes

mended.

As near as I could understand, the spat of the natural

mussel which voluntarily fixed itself to the outer rows of posts, attains

about February or March to the size of a grain of flaxseed. In May the

young mussels are about as big as a lentil, and in about two months more

they will attain to the dimensions of a haricot bean-the men of Esnandes

then call the mussel a renouvelain - which is the proper time for

the planting to begin ; and this operation was in progress during my

visit. It is simple but effective. When a few canoe-loads of these young

mussels are required for the seeding of the more inland bouchots, the men

proceed to the single or collecting stakes at the lowest state of the

tide, armed with long poles, having blunt hooks at the end, by means of

which they scrape off the seedlings. The men do not, however, scrape off

more of the mussels than they require for the operation in hand, which

must be completed before the flow of the next tide. Having filled a few

baskets, each man paddles his canoe to the seat of work, and there

commences the first stage of the work or planting, which is effected in a

curious but characteristic way, the operation being called

la batisse by those engaged in it. Taking a good

handful of the mussels, they are skilfully tied up by the boucholier in a

bag of old netting or canvas, and then deftly fastened in the interstices

of the palisades, or bouchot basket-work, each group of mussels being, of

course, fastened at such a distance as to have plenty of room to grow.

Left there, the byssus of the animal soon forms a point of attachment ;

and the bag rotting away by means of the water, speedily leaves the

mussels hanging in numerous vine-like clusters on the bouchots, where they

increase in size with such great rapidity, as speedily to demand the

performance of the next operation in mussel-culture, which is called the

transplanting. It is conducted with a view to the attainment of two ends :

firstly, the thinning of overcrowded bouchots ; and, secondly, to bring

the ripe mussels gradually nearer to the shore, so as to make their

removal all the more easy at the proper time. The change of habitation is

effected precisely as has already been described ; the mussels are again

tied up in purses of old netting, although not so particularly as before ;

again the mussel, whose power in this way is well known, weaves itself a

new cable, and the bivalve clings to its new resting -place as tenaciously

as ever. It may be asked, why the mussel-farmers should so plant the

mussels as that they will require constant thinning; but the reason is,

that it is desirable for the purpose of their proper fattening that the

mussels should be always, if possible, covered by the salt water ; this,

however, is not compatible with the extent of the crop ; but all that can

be done is done, and the mussels are kept in the front-ranks as long as

possible. A third and last change brings the mussels as near the shore as

they can ever get, so long as they are ungathered.

The labour of planting and transplanting goes on

incessantly, till all the spat that had found a resting-place on the

solitary stakes-that is, the advanced guard-has been dealt with. The

labour of all these varied operations is constant, and is carried on by

old and young, male and female, both day and night, at times when the tide

is suitable. Some portions of the farm are always under water ; other

portions of it, again, are uncovered at the ebbing of the tide; and this

circumstance, I was told, has a great influence on the quality of the

mussel ; those being the best, as may be supposed, which are longest

submerged, and kept at the greatest distance from the mud. Although the

greatest possible care is taken to keep the mussels from being affected by

the copious muddy deposits of the place, by means of allowing a good flow

of water between the base of the bouchots and the sea-surface, yet some of

the bunches become deteriorated, in spite of all the precautions that can

be taken. This, of course, distresses the boucholiers, as one of their

points is the superior flavour of their produce; indeed, it was the

superiority of the mussels, as discovered by accident through Walton's

bird-net, which was set so as, to float high above the mud-the

quality of the mussel more than the quantity - that influenced Walton to

commence as a mussel-farmer ; and to this day it is still quality more

than quantity that the boucholiers study at Esnandes. After the process of

about a year's farming has been undergone, the

mussels are considered to be ready for the market, and

by the care of the farmer, the mussels are in season all the year round,

although, of course, not so good for food at some periods of the year as

at others ; thus, the Aiguillon mussels are not so fine in the spring

months as they are in the autumnal periods of the year, when they became

deliciously fat and savoury ; indeed, I can bear testimony, having had a

feast of them, to the fact of their being better, larger in size, and more

pronounced in their flavour, than any of the British mussels I have

tasted. About April the mussels become milky and unpalatable, although

there are still many branches of them fit for the market. It is in the

months between July and January that the great harvest goes on, and the

chief moneybusiness is done. If the mussels are to be sent to a distance,

they are separated and cleared from all kinds of dirt, packed in hampers

and bags, and sent away on the backs of horses or in carts ; while those

required for more local consumption are kept in pits dug at the bottom of

the cliff, and within the enclosure where the men keep the trousseau of

the bouchots. There are no less than a hundred and forty horses and about

a hundred carts engaged in the trade ; and the mussels are distributed

within a radius of about a hundred miles of Esnandes, more than thirty

thousand journeys being made in the service. In addition to this

land-carrying, forty or fifty barques are in the habit of visiting the

port, to bear away the mussels to still greater distances, making in all

about seven hundred and fifty voyages per annum.

Does the mussel-farm pay? will, of course, be asked by

practical people. Yes, it pays. I have obtained the following figures to

show that mussel-farming pays very well, not to speak of what is obtained

by the round and flat fish which are daily captured through the peculiar

construction of the bouchots. Every bouchot will yield a load of mussels

for each metre of its length ; and this load is of the value of six francs

; and the whole farm at Esnandes is said to yield an annual revenue of

about a million and a quarter of francs, or, to speak roundly, upwards of

fifty-two thousand pounds per annum ; and when it is taken into account

that this large sum of money is, as nearly as possible, a gift from nature

to the inhabitants, as there is no rent to pay for the farm, no seed -as

is the case at the Whitstable oyster-farm-to provide, no manure to

buy-only the labour necessary for cultivation to be given, British

fishermen will easily comprehend the advantages to be derived from

mussel-farming.

[Since my visit to Esnandes several changes have been

made at the mussel-farm-more especially in the disposition of the Bouchots-but

there is no difference in the mode of culture.]