|

Description of the Oyster - Controversies about Oyster-Life - Do Oysters

live upside down? - The Spawning of Oysters - Oyster-Growth - When do

Oysters become reproductive for Dredging? - Sergins Orata - Lake Fusaro

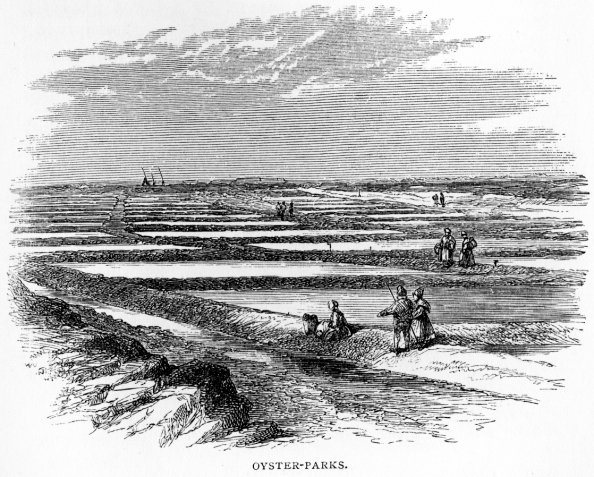

- Oyster-Fascines - Ile de Re, and Growth of the Park System - Economy

of the Parks - Greening the Oyster - Oyster-Growth - Spat Collectors -

Miscellaneous Facts.

Zoologically the oyster is known as Ostraea edulis.

Its outward appearance is familiar to even very landward people, and

no human engineer could have invented so admirable a home for the pulpy

and headless mass of jelly that is contained within the rough-looking

shell. Many curious opinions have been held about this shell-fish. At one

time oysters were thought to be only masses of oily or other matter,

scarcely alive and insensible to pain. Who would suppose, it was asked,

that a portion of blubber like the oyster, that could only have been first

eaten by some very courageous individual, would have any feeling? But we

know better now, and although the organisation of the mollusca is not of a

high order, it is perfect of its kind, and has within it indications of

organs that in beings of a higher type serve a loftier purpose, and point

out the beginnings of nature, showing how she works her way from the

simplest imaginings of animal life to the complex human machine. The

oyster has no doubt in its degree many joys and sorrows, and throbs with

life and pleasure, as animals do that have a higher organic structure. The

oyster is curiously constructed; but I fear that, comparatively speaking,

very few of my readers have ever seen a perfect one, as oysters are very

much mutilated, being generally deprived of their beards before they are

sent to table, and otherwise hurt, both accidentally in the opening and by

use and wont, as in the case of the beard. Its mouth—it has no jaws or

teeth—is a kind of trunk or snout, with four lips, and leafy coverings or

gills are spread over the body to act as lungs, and keep from the action

of the water the air which the animal requires for its existence. This

covering is divided into lobes with ciliated edges. Four leaves or

membranous plates act as capillary funnels, open at the farthest

extremities. Behind the gills there is a large whitish fatty part

enclosing the stomach and intestines. The vessels of circulation play into

muscular cavities, which act the part of the heart. The stomach is

situated near the mouth. The oyster has no feet, but can move by opening

and closing its shell, and it secures food by means of its beard, which

acts as a kind of rake. In fact the internal structure of the oyster,

while it is excellently adapted to that animal's mode of life, is

exceedingly simple.

It is not my purpose in the present work to enter into

the minutiae of oyster life. Indeed, there have been so many controversies

about the natural history of this animal as to render it impossible to

narrate in the brief space I can devote to it a tenth part of what has

been written or spoken about the life and habits of the " broody

creature." Every stage of its growth has been made the stand-point for a

wrangle of some kind. As an example of the keenness with which each stage

of oyster life is now being discussed, I may mention that some years ago a

most amusing squabble broke out in the pages of the Field newspaper on an

immaterial point of oyster life, which is worth noting here as an example

of what can be said on either side of a question. The controversy hinged

upon whether an oyster while on the bed lay on the flat or convex side.

Mr. Frank Buckland, who originated the dispute, maintained that the right,

proper, and natural position of the oyster, when at the bottom of the sea,

is with the flat shell downwards; but the natural position of the oyster

is of no practical importance whatever; and I know, from personal

observation of the beds at Newhaven and Cockenzie, that oysters lie both

ways,-indeed, with a dozen or two of dredges tearing over the beds it is

impossible but that they must lie quite higgledy-piggledy, so to speak. A

great deal that is incidentally interesting was brought up in the Field

discussion. There have been several other disputes about points in the

natural history of the oysters-one in particular as to whether that animal

is provided with organs of vision. Various opinions have been enunciated

as to whether an oyster has eyes, and one author asserts that it has so

many as twenty-four, which again is denied, and the assertion made that

the so-called eyes projecting from the border of the mantle have no

optical power whatever ; but, be that as it may, the oyster has a power of

knowing the light from the dark.

As is well known, there is a period every year during

which the oyster is not fished ; and the reason why our English

oyster-beds have not been ruined or exhausted by over fishing arises,

among other causes, from there being a definite close-time assigned to the

breeding of the mollusc. It would be well if the larger varieties of sea

produce were equally protected ; for it is sickening to observe the

countless numbers of unseasonable fish that are from time to time brought

to Billingsgate and other markets, and greedily purchased. The fact that

oysters are supplied only during certain months in the year, and that the

public have a general corresponding notion that they are totally unfit for

food during May, June, July, and August (those four wretched months which

have not the letter "r" in their names), has been greatly in their favour.

Had there been no period of rest, it is almost certain that oysters would

long ago -I allude to the days when there was no system of cultivation

-have become extinct.

Oysters begin to sicken about the end of April, so that

it is well that their grand rest commences in May. The shedding of the

spawn continues during the whole of the hot monthsnot but that during that

period there may be found supplies of healthy oysters, but, as a general

rule, it is better that there should be a total cessation of the trade

during the summer season, because were the beds disturbed by a search for

the healthy oysters the spawn would be scattered and destroyed.

Oysters do not leave their ova, like many other marine

creatures, but incubate them in the folds of their mantle, and among the

lamina; of their lungs. There the ova remain surrounded by mucous matter,

which is necessary to their development, and within which they pass

through the embryo state. The mass of ova, or "spat" as it is familiarly

called, undergoes various changes in its colour, meanwhile losing its

fluidity. This state indicates, it has been said, the near termination of

the development and the sending forth of the embryo to an independent

existence, for by this time the young oysters can live without the

protection of the maternal organs. An eminent French pisciculturist says

that the animated matter escaping from the adults on breeding-banks is

like a thick mist being dispersed by the winds-the spat is so scattered by

the waves that only an imperceptible portion remains near the parent

stock. All the rest is dissipated over the sea space ; and if these

myriads of animalculae, tossed by the waves, do not meet with solid bodies

to which they can attach themselves, their destruction is certain, for if

they do not fall victims to the larger animals which prey upon them, they

are unfortunate in not fixing upon the proper place for their thorough

development.

Thus we see that the spawn of the oyster is well

matured before it leaves the protection of the parental shell ; and by the

aid of the microscope the young animal can be seen with its shell perfect

and its holding-on apparatus, which is also a kind of swimming-pad, ready

to clutch the first "coigne of vantage" that the current may carry it

against. My " theory " is, that the parent oyster goes on brewing

its spawn for some time-I have seen it oozing from the same animal for

some days-and it is supposed that the spawn swims about with the current

for a short period before it falls, being in the meantime devoured by

countless sea animals of all kinds. The operation of nursing, brewing, and

exuding the spat from the parental shell will occupy a considerable

period-say from two to four weeks. It is quite certain that the close-time

for oysters is necessary and advantageous, for we seldom find this mollusc,

as we do the herring and other fish, full of eggs, so that most of the

operations connected with its reproduction go on in the months during

which there is no dredging. As I have indicated, immense quantities of the

spawn of oysters are annually devoured by other molluscs, and by fish and

crustaceans of various sizes ; it is well, therefore, that it is so

bountifully supplied. On occasions of visiting the beds I have seen the

dredge covered with this spawn ; and no pen could number the thousands of

millions of oysters thus prevented from ripening into life. Economists

ought to note this fact with respect to fish generally, for the enormous

destruction of spawn of all kinds must exercise a very serious influence

on our fish supplies. I may also note that the state of the weather has a

serious influence on the spawn and on the adult oyster-power of spawning.

A cold season is very unfavourable, and a decidedly cold day will kill the

spat.

Some

people have asserted that the oyster can reproduce its kind in twenty

weeks, and that in ten months it is fullgrown. Both of these assertions

are pure nonsense. At the age of three months an oyster is not much bigger

than a pea, and the age at which reproduction begins has never been

accurately ascertained, but it is thought to be three years. I give here

one or two illustrations of oystergrowth in order to show the ratio of

increase. The smallest, about the Some

people have asserted that the oyster can reproduce its kind in twenty

weeks, and that in ten months it is fullgrown. Both of these assertions

are pure nonsense. At the age of three months an oyster is not much bigger

than a pea, and the age at which reproduction begins has never been

accurately ascertained, but it is thought to be three years. I give here

one or two illustrations of oystergrowth in order to show the ratio of

increase. The smallest, about the

dimensions

of a pin's head, may be called a fortnight old. The next size represents

the oyster as it appears when three months old. The other sizes are drawn

at the ages of five, eight, and twelve months respectively. Oysters are

usually four years old before they are sent to the London market. At the

age of five years the oyster is, I think, in its prime ; and some of our

most intelligent fishermen think its average duration of life to be ten

years. dimensions

of a pin's head, may be called a fortnight old. The next size represents

the oyster as it appears when three months old. The other sizes are drawn

at the ages of five, eight, and twelve months respectively. Oysters are

usually four years old before they are sent to the London market. At the

age of five years the oyster is, I think, in its prime ; and some of our

most intelligent fishermen think its average duration of life to be ten

years.

In

these days of oyster-farming the time at which the oyster becomes

reproductive may be easily fixed, and it will no doubt be found to vary in

different localities. At some places it becomes saleable-chiefly, however,

for fattening in the course of two years ; at other places it is three or

four years before it becomes a saleable commodity; but on the average it

will be quite safe to assume that at four years the oyster is both ripe

for sale and able for the reproduction of its kind. Let us hope that the

breeders will take care to have at least one brood from each batch before

they offer any for sale. Oyster-farmers should keep before them the folly

of the salmon-fishers, who kill their grilse - i.e. the virgin fish

-before they have an opportunity of perpetuating their race. In

these days of oyster-farming the time at which the oyster becomes

reproductive may be easily fixed, and it will no doubt be found to vary in

different localities. At some places it becomes saleable-chiefly, however,

for fattening in the course of two years ; at other places it is three or

four years before it becomes a saleable commodity; but on the average it

will be quite safe to assume that at four years the oyster is both ripe

for sale and able for the reproduction of its kind. Let us hope that the

breeders will take care to have at least one brood from each batch before

they offer any for sale. Oyster-farmers should keep before them the folly

of the salmon-fishers, who kill their grilse - i.e. the virgin fish

-before they have an opportunity of perpetuating their race.

Another point on which naturalists differ is as to the

quantity of spawn from each oyster. Some enumerate the young by thousands,

others by millions. It is certain enough that the number of young is

prodigious-so great, in fact, as to prevent their all being contained in

the parent shell at one time ; but I do not believe that an oyster yields

its young " in millions "perhaps half a million is on the average the

amount of spat which each oyster can "brew" in one season. I have examined

oyster-spawn (taken direct from the oyster) by means of a powerful

microscope, and find it to be a liquid of some little consistency, in

which the young oysters, like the points of a hair, swim actively about,

in great numbers, as many as a thousand having been counted in a very

minute globule of spat. The spawn, as found floating on the water, is

greenish in appearance, and each little splash may be likened to an oyster

nebula, which resolves itself, when examined by a powerful glass, into a

thousand distinct animals.

The oyster, it is now pretty well determined, is

hermaphrodite, and it is very prolific, as has been already observed, but

the enormous fecundity of the animal is largely detracted from by bad

seasons ; for, unless the spawning season be mild, soft, and warm, there

is usually a very partial full of spat, and

of course quite a scarcity of brood ; and even if one be the proprietor of

a large bed of oysters, there is no security for the spawn which is

emitted from the oysters on that bed falling upon it, or within the bounds

of one's own property even ; it is often enough the case that the spawn

falls at a considerable distance from the place where it has been emitted.

Thus the spawn from the Whitstable and Faversham Oyster Companies' beds -

and these contain millions of oysters in various stages of progress -falls

usually on a large piece of ground between Whitstable and the Isle of

Thanet, formerly common property, but lately given by Act of

Parliament to a company recently formed for the breeding of oysters. The

saving of the spawn cannot be effected unless it falls on proper ground -

i.e. ground with a shelly bottom is best, for the infant animal is sure to

perish if it fall among mud or upon sand ; the infant oyster must obtain a

holding-on place as the first condition of its own existence. Oysters have

not on the aggregate spawned extensively during late years. The greatest

fall of spawn ever known in England occurred forty-six years ago. On being

exuded from the parental shell, the spawn of the oyster at once rises to

the surface, where its vitality is easily affected, and it is often killed

in certain places by snow-water or ice. A genial warmth of sunshine and

water is considered highly favourable to its proper development during the

few days it floats about on the surface. It is thought that not more than

one oyster out of each million arrives at maturity. It is curious to note

that some oysters have immense shells with very little " meat " in them. I

recently saw in a restaurant several oysters, much larger externally than

crownpieces, with the " meat " about the size of a sixpence: these were

Firth of Forth oysters from Cockenzie. It is not easy to determine from

the external size of the animal the amount of " meat " it will

yield-apparently, " the bigger the oyster the smaller the meat." In the

early part of the season only very small oysters are sold in Edinburgh-the

reason assigned being that all the best dredgers are " away at the

herring," and that the persons left behind at the oyster-beds are only

able to skim them, so that, for a period of about six weeks, we merely

obtain the small fry that are lying on the top. It is quite certain that

as the season advances the oysters obtained are larger and of more decided

flavour. In the "natives" obtained at Whitstable the shell and the meat

are pretty much in keeping as to size, and this is an advantage.

The Abbé Diquemarc, who has keenly observed the habits

of the principal mollusca, assures us that oysters, when free, are

perfectly able to transport themselves from one place to another, by

simply causing the sea-water to enter and emerge suddenly from between

their valves ; and these they use with extreme rapidity and great force.

By means of the operation now described, the oyster is enabled to defend

itself from its enemies among the minor crustacea, particularly the small

crabs, which endeavour to enter the shell when it is half open. "Some

naturalists," the Abbé says, "go the length of allowing the oyster to have

great foresight," which he illustrates by an allusion to the habits of

those found at the sea-side. "These oysters," he says, "exposed to the

daily change of tides, appear to be aware that they are likely to be

exposed to dryness at certain recurring periods, and so they preserve

water in their shells to supply their wants when the tide is at ebb. This

peculiarity renders them more easy of transportation to remote distances

than those members of the family which are caught at a considerable

distance from the shore."

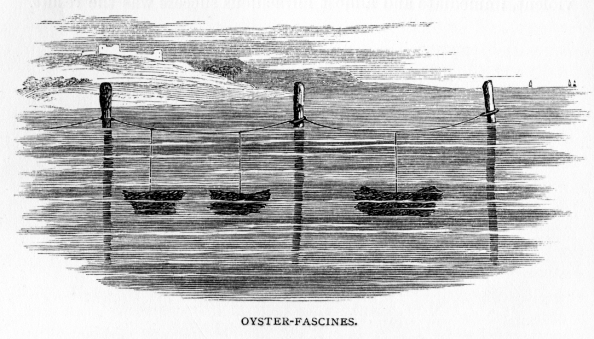

The secret of there being only a holding-on place

required for the spat of the oyster to insure an immensely-increased

supply having been penetrated by the French people-and no doubt they are

in some degree indebted to our oyster-beds on the Colne and at Whitstable

for their idea-the plan of systematic oyster-culture was easy enough, as I

will immediately show. A few initiatory experiments, in fact, speedily

settled that oysters could be grown in any quantity. Strong pillars of

wood were driven into the mud and sand ; arms were added; the whole was

interlaced with branches of trees, and various boughs besides were hung

over the beds on ropes and chains, whilst others were sunk in the water

and kept down by a weight. A few boat-loads of oysters being laid down,

the spat had no distance to travel in search of a home, but found a

resting-place almost at the moment of being exuded; and, as the fairy

legends say, " it grew and it grew," till, in the fulness of time, it

became a marketable commodity.

But the history of this modern phase of oyster-farming,

as practised on the foreshores of France, is so interesting as to demand

at my hands a rather detailed notice, for it is one of the most noteworthy

circumstances connected with the revived art of fish-culture, that it has

resulted in placing upon the shores of France a countless number of

fish-farms for the cultivation of the oyster alone.

It is no exaggeration to say, that about twenty-five

years ago there was scarcely an oyster of native growth in France ; the

beds-and I cite the case of France as a warning to people at home, I mean

as regards our Scottish oyster-beds-had become so exhausted from

overdredging as to be unproductive, so far as their money value was

concerned, and to be totally unable to recover themselves so far as their

power of reproductiveness was at stake. And the people were consequently

in despair at the loss of this favourite adjunct of their banquets, and

had to resort to other countries for such small supplies as they could

obtain. As an illustration of the overdredging that had prevailed, it may

be stated that oyster-farms which formerly employed 1400 men, with 200

boats, and yielded an annual revenue of 400,000 francs, had become so

reduced as to require only 100 men and 20 boats. Places where at one time

there had been as many as fifteen oyster-banks, and great prosperity among

the fisher class, had become, at the period I allude to, almost oysterless.

St. Brieuc, Rochelle, Marennes, Rochefort, etc., had all suffered so much

that those interested in the fisheries were no longer able to stock the

beds, thus proving that, notwithstanding the great fecundity of these sea

animals, it is quite possible to overfish them, and thoroughly exhaust

their reproductive power. It was under these circumstances that M. Coste

instituted that plan of oyster-culture which has been so much noticed of

late in the scientific journals, and which appears to have been inspired

by the plan of the musselfarms in the Bay of Aiguillon, and the

oyster-pares of Lake Fusaro, so far at least as the principle of

cultivation is concerned. At the instigation of the French Government, he

made a voyage of exploration round the coasts of France and Italy, in

order to inquire into the condition of the sea-fisheries, which were, it

was thought, in a declining condition. It was his "mission," and he

fulfilled it very well, to see how these marine fisheries could be

artificially aided, as the fresh-water fisheries had been aided through

the re-discovery by Joseph Remy of the long-forgotten plan of pisciculture,

as already detailed in a preceding portion of this work.

The breeding of oysters was a business pursued with

great assiduity during what I have called the gastronomic age of Italy,

the period when Lucullus kept a stock of fish valued at £50,000 sterling,

and Sergius Orata invented the art of oysterculture. There is not a great

deal known about this ancient gentleman, except that he was an epicure of

most refined taste (the " master of luxury " he was called in his own

day), and some writers of the period thought him a very greedy person, a

kind of dealer in shell-fish. It was thought also that he was a

housebroker or person who bought or built houses, and having improved

them, sold them to considerable advantage. He received, however, an

excellent character, while standing his trial for using the public waters

of Lake Lucrinus for his own private use, from his advocate Lucinus

Crassus, who said that the revenue officer who prevented Orata was

mistaken if he thought that gentleman would dispense with his oysters,

even if he was driven from the Lake of Lucrinus, for, rather than not

enjoy his molluscous luxury, he would grow them on the tops of his houses.

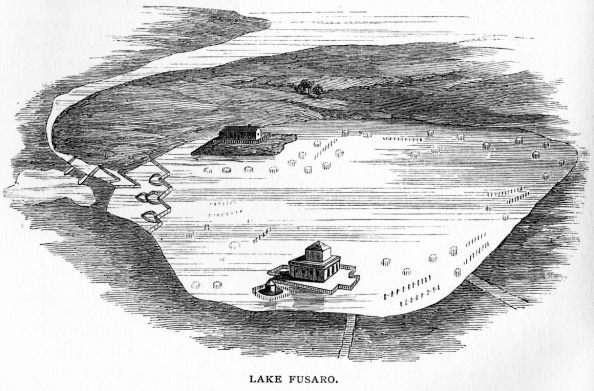

Lake Fusaro, of which I give a kind of bird's-eye view,

is highly interesting to all who take an interest in the prosperity of the

fisheries, as the first seat of oyster-culture. It is the Avernus of

Virgil, and is a black volcanic-looking pool of water, about a league in

circumference, which lies between the site of the Lucrine Lake-the lake

used by Orata - and the ruins of the town of Cumae. It is still extant,

being even now, as I have said, devoted to the highly profitable art of

oyster-farming, yielding, as has often been published, from this source an

annual revenue of about £1200. This classic sheet of water was at one time

surrounded by the villas of the wealthy Italians, who frequented the place

for the joint benefit of the sea-water baths, and the shell-fish

commissariat, which had been established in the two lakes (Avernus and

Lucrine). The place, which, before then, was overshadowed by thick

plantations, had been consecrated by the superstitious to the use of the

infernal gods.

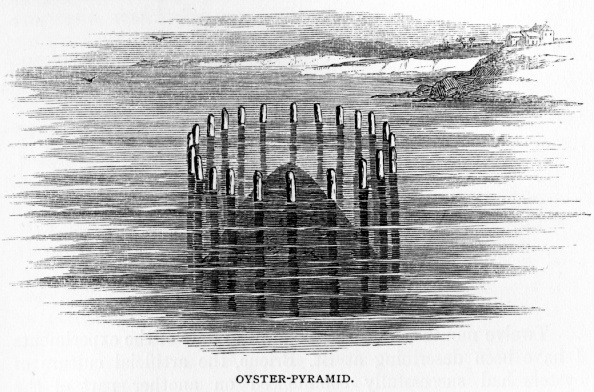

The mode of oyster-breeding at this place, then as now,

was to erect artificial pyramids of stones in the water, surrounded by

stakes of wood, in order to intercept the spawn, the oyster being laid

down on the stones. I have shown these modes in the accompanying

engravings. Faggots of branches were also

The accompanying engraving gives a general view of Lake

Fusaro (the Avernus of the ancients), showing here and there the stakes

surrounding the artificial banks, the single and double ranges of stakes

on which the faggots are suspended, and at one extremity the labyrinths,

in the face of which is a canal of from 2y' to 3 metres broad and 1 1/2

metre deep joining the lake to the sea. A small lake, believed to be the

ancient Cocytus, communicates with this canal. The pavilion in the lake is

the ordinary residence of the persons in charge of the fishery.

used to collect the spawn, which, as I have already

said, requires, within forty-eight hours of its emission, to secure a

holding-on place or be lost for ever. The plan of the Fusaro

oyster-breeders struck M. Coste as being eminently practical and suitable

for imitation on the coasts of France: he had one of the stakes pulled up,

and was gratified to find it covered with oysters of all ages and sizes.

The Lake Fusaro system of cultivation was therefore, at the instigation of

Professor Coste, strongly recommended for imitation by the French

Government to the French people, as being the most suitable to follow, and

experiments were at once entered upon with a view to prove whether it

would be as practicable to cultivate oysters as easily among the agitated

waves of the open sea as in the quiet waters of Fusaro. In order to settle

this point, it was determined to renew the old oyster-beds in the Bay of

St. Brieuc, and notwithstanding the fact that the water there is

exceedingly deep and the winds very violent, immediate and almost

miraculous success was the result.

The fascines laid down soon became covered with seed,

and branches were speedily exhibited at Paris, and other places,

containing thousands of young oysters. The experiments in oysterculture

tried at St. Brieuc were commenced early, on part of a space of 3000 acres

that was deemed suitable for the reception of spat. A quantity of breeding

oysters, approaching to three millions, was laid down either on the old

beds or on newly-constructed longitudinal banks ; these were sown thick on

a bottom composed chiefly of immense quantities of old shells-the "middens"

of Cancale in fact, where the shell accumulation had become a nuisance-so

that there was a more than ordinary good chance for the spat finding at

once a proper holding-on place. Then again, over some of the new banks,

fascines made of boughs tightly tied together were sunk and chained over

the beds, so as to intercept such portions of the spawn as were likely,

upon rising, to be carried away by the force of the tide. In less than six

months the success of the operation in the Bay of St. Brieuc was assured ;

for, at the proper season, a great fall of spawn had occurred, and the

bottom shells were covered with the spat, while the fascines were so

thickly coated with young oysters that an estimate of 20,000 for each

fascine was not thought an exaggeration.

Twelve months, however, before the date of the

experiments I have been describing at St. Brieuc, the artificial culture

of oysters had successfully commenced on another part of the coast-namely,

the Ile de Re off the shore of the lower Charente (near la Rochelle), in

the Bay of Biscay, which may now be designated the capital of French

oysterdom, having more parcs and claires than Marennes,

Arcachon, Concarneau, Cancale, and all the rest of the coast put together,

and which, before it became celebrated for its oyster-growing, was only

known, in common with other places in France, for its successful culture

of the vine. It is curious to note the rapid growth of the industry of

oyster-culture on the Ile de Re. It was begun so recently as 1858, and

there are now upwards of 4000 parks and claires upon its shores, and the

people may be seen as busy in their fish-parks as the market-gardeners of

Kent in their strawberrybeds. Oyster-farming on the Ile was inaugurated by

one Boeuf, a stone-mason. This shrewd fellow, who was a keen observer of

nature, and had seen the oyster-spat grow to maturity, began thinking of

oyster-culture simultaneously with Professor Coste, and wondering if it

could be carried out on those portions of the public foreshore that were

left dry by the ebb of the waters. He determined to try the experiment on

a small scale, so as to obtain a practical solution of his " idea," and,

with this view, he enclosed a small portion of the foreshore of the island

by building a rough dyke about eighteen inches in height. In this park lie

laid down a few bushels of growing oysters, placing amongst them a

quantity of large stones, which he gathered out of the surrounding mud.

This initiatory experiment was so successful, that in the course of a year

he was able to sell £6 worth of oysters from his stock. This result was of

course very encouraging to the enterprising mason, and the money was just

in a sense found money, for the oysters went on growing while he was at

work at his own proper business as a mason. Elated by the profit of his

experiment, he proceeded to double the proportions of his park, and by

that means more than doubled his oyster commerce, for, in 1861, he was

able to dispose of upwards of £30 worth, and this without impoverishing,

in the least degree, his breeding stock. He continued to increase the

dimensions of his farm, so that by 1862 his sales had increased to £40. As

might have been expected, Boeuf's neighbours had been carefully watching

his experiments, uttering occasional sneers, no doubt, at his enthusiasm ;

but, for all that, quite ready to go and do likewise whenever the success

of the industrious mason's experiments became sufficiently developed to

show that they were profitable as well as practical. After Boeuf had

demonstrated the practicability of oyster-farming, the extension of the

system over the foreshores of the island, between Point de Rivedoux and

Point de Lome, was rapid and effective ; so much so that two hundred beds

were conceded by the Government previous to 1859, while an additional five

hundred beds were speedily laid down, and in 1860 large quantities of

brood were sold to the oyster-farmers at Marennes, for the purpose of

being manufactured into green oysters in their claires on the banks of the

river Seudre. The first sales after cultivation had become general

amounted to £126, and the next season the sum reached in sales was upwards

of £500, and these monies, be it observed, were for very young oysters ;

because, from an examination of the dates, it will at once be seen that

the brood had not had time to grow to any great size. So rapid indeed has

been the progress of oyster-culture at the Ile de Re, that what were

formerly a series of enormous and unproductive mud-banks, occupying a

stretch of shore about four leagues in length, are now so trans-formed,

and the whole place so changed, that it seems the work of a miracle.

Various gentlemen who have inspected these farms for the cultivation of

oysters speak with great hopefulness about the success of the experiment.

Mr. Ashworth, so well known for his success as a salmon fisher and breeder

in Ireland, tells me that oyster-farming on the shores of the French coast

is one of the greatest industrial facts of the present age, and thinks

that oyster-farming will in the end be even more profitable than

salmon-breeding. There is only one drawback connected with these and all

other sea-farms in France : the farmers, we regret to say, are only

"tenants at will," [Mr. Ashworth, in a communication to Mr. Barry, one of

the Commissioners of Irish Fisheries, says-"No charge is made for the

oyster-parks, but each plot is marked and defined on a map, and the

produce is considered to be the private property of the person who

establishes it. They vary in size twenty or thirty yards square, the stone

or tiles are placed in rows about five feet apart, with the ends open so

as to admit of the wash of the tide in and out."] and liable at any moment

to be ejected ; but notwithstanding this disadvantage the work of

oyster-culture still goes bravely forward, and it is calculated, in spite

of the bad spatting of the last three years, that there is a stock of

oysters in the beds on the Ile de Reaccumulated in only six years-of the

value of upwards of £100,000.

Much hard work had no doubt to be endured before such a

scene of industry could be thoroughly organised. When the great success of

Boeuf's experiments had been proclaimed in the neighbourhood, a little

army of about a thousand labourers came down from the interior of the

country and took possession, along with the native fishermen, of the

shores, portions of which were conceded to them by the French Government

at a nominal rent of about a franc a week, for the purpose of being

cultivated as oyster parks and claires. The most arduous duty of these men

consisted in clearing off the mud, which lay on the shore in large

quantities, and which is fatal to the oyster in its early stages ; but

this had to be done before the shores could be turned to the purpose for

which they were wished. After this preliminary business had been

accomplished, the rocks had to be blasted in order to find stones for the

construction of the park-walls ; then these had to be built, and the

ground had also to be paved in a rough-and-ready kind of way ; foot-roads

had also to be arranged for the convenience of the farmers, and

carriage-ways had likewise to be made to admit of the progress of vehicles

through the different farms. Ditches had to be contrived to carry off the

mud ; the parks had to be stocked with breeding oysters, and to be kept

carefully free from the various kinds of sea animals that prey upon the

oyster ; and many other daily duties had to be performed that demanded the

minute attention of the owners. But all obstacles were in time overcome,

and some of the breeders have been so very

successful of late years as to be offered a sum of £100

for the brood attached to twelve of their rows of stones, the cost of

laying these down being about two hundred francs! To construct an

oyster-bed thirty yards square costs about £12 of English money, and it

has been calculated that the return from some of the beds haa been as high

as 1000 per cent! The whole industry of the Ile is wonderful when it is

considered that it has been all organised in a period of seven years.

Except a few privately-kept oysters, there was no oyster establishment on

the island previous to 1858.

Some gentlemen from the island of Jersey who visited Re

report that an incredible quantity of oysters has been produced on that

shore, which a few years ago was of no value, so that this branch of

industry now realises an extraordinary revenue, and spreads comfort among

a large number of families who were previously in a state of comparative

indigence. But more interesting even than the material prosperity that has

attended the introduction of this industry into the island of Re

is the moral success that has accrued to the

experiment. Excellent laws have been enacted by the oyster-farmers

themselves for the government of the colony. A kind of parliament has been

devised for carrying on arguments as to oyster-culture, and to enable the

four communities, into which the population has been divided, to

communicate to each other such information as may be found useful for the

general good of all engaged in oyster-farming. Three delegates from each

of the communities are elected to conduct the general business, and to

communicate with the Department of Marine when necessary.

A small payment is made by every farmer as a

contribution to the general expense, while each division of the community

employs a special watchman to guard the crops, and see that all goes on

with propriety and good faith ; and although each of the oyster-farmers of

the Ile de Re cultivates his own park or claire for his own sole profit

and advantage, they most willingly obey the general laws that have been

enacted for the good of the community. It is pleasant to note this. We

cannot help being gratified at the happy moral results of this wonderful

industry, and it will readily be supposed that with both vine-culture (for

the islanders have fine vineyards) and oyster-culture to attend to, these

farmers are kept very busy. Indeed, the growing commerce-the export of the

oysters, and the import of other commodities for the benefit of so

industrious a population-incidental to such an immense growth of shellfish

as can be carried on in the 4000 parks and claires which stud the

foreground of Re must be arduous ; but as the labour is highly

remunerative, the labourers have great cause for thankfulness. It is

right, however, to state that, with all the care that can be exercised,

there is still an enormous amount of waste consequent on the artificial

system of culture; the present calculation is, that even with the best

possible mode of culture the average of reproduction is as yet only

fourteenfold; but it is hoped by those interested that a much larger ratio

of increase will be speedily attained. This is desirable, as prices have

gone on steadily increasing since the time that Boeuf first experimented.

In 1859 the sales were effected at about the rate of fifteen shillings per

bushel, for the lowest qualities-the highest being double that price ;

these were for fattening in the claires, and when sold again they brought

from two to three pounds per bushel.

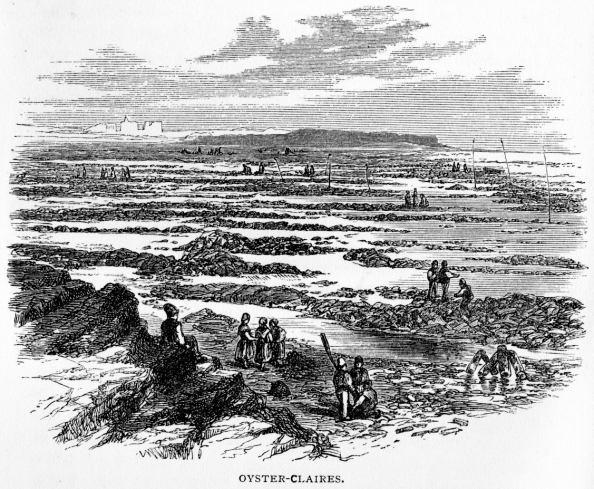

One of the most lucrative branches of foreign

oyster-farming may be now described - i.e. the manufacture of the

celebrated green oysters. The greening of oysters, many of which are

brought from the Ile de Re parks, is extensively carried on at Marennes,

on the banks of the river Seudre, and this particular branch of oyster

industry, which extends for leagues along the river, and is also

sanctioned by free grants from the State, has some features that are quite

distinct from those we have been considering, as the green oyster is of

considerably more value than the common white oyster. The peculiar colour

and taste of the green oyster are imparted to it by the vegetable

substances which grow in the beds where it is manipulated. This statement,

however, is scarcely an answer to the question of "why," or rather "how,"

do the oysters become green? Some people maintain that the oyster green is

a disease of the liver-complaint kind, whilst there are others who

attribute the green colour to a parasite that overgrows the mollusc. But

the mode of culture adopted is in itself a sufficient answer to the

question. The industry carried on at Marennes consists chiefly of the

fattening in claires, and the oysters operated upon are at one period of

their lives as white as those which are grown at any other place; indeed

it is only after being steeped for a year or two in the muddy ponds of the

river Seudre that they attain their much-prized green hue. The enclosed

ponds for the manufacture of these oysters-and, according to all epicurean

authority, the green oyster becomes "the oyster par excellence" require to

be water-tight, for they are not submerged by the sea, except during very

high tides. Each claire is about one hundred feet square. The walls for

retaining the waters require therefore to be very strong; they are

composed of low but broad banks of earth, five or six feet thick at the

base and about three feet in height. These walls are also useful as

forming a promenade on which the watchers or workers can walk to and fro

and view the different ponds. The flood-gates for the admission of the

tide require also to be thoroughly watertight and to fit with great

precision, as the stock of oysters must always be kept covered with water

; but a too frequent flow of the tide over the ponds is not desirable,

hence the walls, which serve the double purpose of both keeping in and

keeping out the water. A trench or ditch is cut in the inside of each pond

for the better collection of the green slime left at each flow of the

tide, and many tidal inundations are necessary before the claire is

thoroughly prepared for the reception of its stock. When all these matters

of construction and slime-collecting have been attended to, the oysters

are then scattered over the ground, and left to fatten. When placed in

these greening claires they are usually from twelve to sixteen months old,

and they must remain for a period of two years at least before they can be

properly greened, and if left a year longer they are all the better; for I

maintain that an oyster should be at least about four years old before it

is sent to table. In a privately-printed pamphlet on the French

oyster-fisheries, sent to me by Mr. Ashworth, it is stated that oysters

deposited in the claires for feeding possess the same powers of

reproduction as those kept in the breedingponds. " Their progeny is

deposited in the same profusion, but that progeny not coming in contact

with any solid body, it inevitably perishes, unless it can attach itself

to the vertical sides of some erection." A very great deal of attention

must be devoted to the oysters while they are in the greening-pond, and

they must be occasionally shifted from one pond to another to ensure

perfect success. Many of the oyster-farmers of Marennes have two or three

claires suitable for their purpose. The trade in these green oysters is

very large, and they are found to be both palatable and safe, the greening

matter being furnished by the sea. Some of the breeders, or rather

manufacturers, of green oysters, anxious to be soon rich, content

themselves with placing adult oysters only in these claires, and these

become green in a very short time, and thus enable the operator to have

several crops in a year without very much trouble. The claires of Marennes

furnish about fifty millions of green oysters per annum, and these are

sold at very remunerative prices, yielding an annual revenue of something

like two and a half millions of francs.

As to the kind of ground

most suitable for oyster-growth, Dr. Kemmerer, of St. Martin's (Ile de

Re), an enthusiast in oyster-culture, gives us a great many useful hints.

I have summarised a portion of his information :-The artificial culture of

the oyster may be considered to have solved an important question-namely,

that the oyster continues fruitful after it is transplanted from its

natural abode in the deep sea to the shores. This removal retards but

never hinders fecundation. The sea oyster, however, is the most prolific,

as the water at a considerable depth is always tranquil, which is a

favourable point in oyster-growth ; but the shore oyster-banks will also

be very productive, having two chances of replenishment-namely, from the

parent oysters in the pares, and from those currents that may float seed

from banks in the sea. Muddy ground is excellent for the growth of oysters

; they grow in such localities very quickly, and become saleable in a

comparatively short space of time. Dry rocky ground is not so suitable for

the young oyster, as it does not find a sufficiency of food upon it, and

consequently languishes and dies. Marl is the most esteemed, and on it the

oyster is said to become perfect in form and excellent in flavour. In the

marl the young oyster finds plenty of food, constant heat, and perfect

quiet. Wherever there is mud and sun there will be

found the little molluscs, crustacea, and swimming

infusoria, which are the food of the oyster. The culture of the oyster in

the mud-ponds and in the marl-a culture which ought some day to become

general-changes completely its qualities ; the albumen becomes fatty,

yellow or green, oily, and of an exquisite flavour. The animal and

phosphorus matter increases, as does the osmozone. This oyster, when fed,

becomes exquisite food. In effecting the culture of the sea-shores and of

the marl-ponds, I am pursuing a practical principle of great importance,

by the conversion of millions of shore oysters, squandered without profit,

into food for public consumption. The green oyster, to this day, has only

been regarded as a luxury for the tables of the rich; but, as I have

indicated, there are an immense number of farms or ponds on the Seudre,

and I would like to see it used as food by everyone."

The French oyster-farmers are happy

and prosperous. The wives assist their husbands in all the lighter

labours, such as separating and arranging the oysters previous to their

being placed on the claires. It is also their duty to sell the oysters;

and for this purpose they leave their home about the end of August, and

proceed to a particular town, there to await and dispose of such

quantities of shell-fish as their husbands may forward to them. In this

they resemble the fisherwomen of other countries. The Scotch fishwives do

all the business connected with the trade carried on by their husbands ;

it is the husbands' duty to capture the fish only, and the moment they

come ashore their duties cease, and those of their wives and daughters

begin with the sale and barter of the fish.

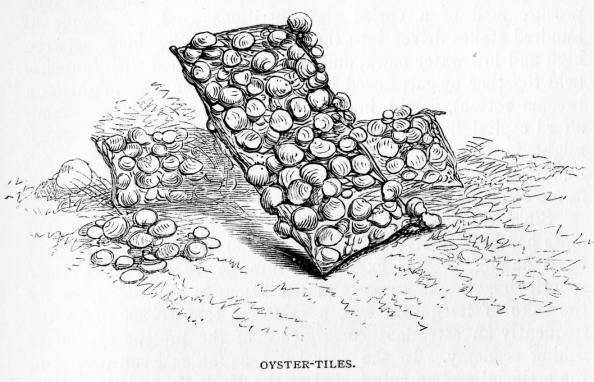

Before going farther, it may be

stated that the best mode of receiving the spawn of the oyster has not

been determined. M. Coste, whose advice is well worthy of being followed,

recommended the adoption of fascines of brushwood to be fixed over the

natural oyster-beds in order to intercept the young ones; others again, as

we have just seen, have adopted the pares, and have successfully caught

the spawn on dykes constructed for that purpose; but Dr. Kemmerer has

invented a tile, which lie covers with some kind of composition that can,

when occasion requires, be easily peeled off, so that the crop of oysters

that may be gathered upon it can be transferred from place to place with

the greatest possible ease, and this plan is useful for the transference

of the oyster from the collecting

parc to the fattening claire.

The annexed drawing will give an idea of the Doctor's invention. The

composition and the adhering oyster may all be stripped off in one piece,

and the tile may be coated for future use. Tiles are exceedingly useful in

aiding the oysterbreeder to avoid the natural enemies of the oyster, which

are very numerous, especially at the periods when it is young and tender.

The oysters may be peeled off the tiles when they are six or seven months

old. Spat-collectors of wood have also been tried with considerable

success. Hitherto these tiles have been very successful, although it is

thought by experienced breeders that no

bottom for oysters is so good as the

natural one of "cultch," as the old oyster-shells are called, but the tile

is often of service in catching the "floatsome," as the dredgers call the

spawn, and to secure that should be one of the first objects of the

oyster-farmer.

We glean from these proceedings of

the French pisciculturists the most valuable lessons for the improvement

and conduct of our British oyster-parks. If, as seems to be pretty

certain, each matured oyster yields about two millions of young per annum,

and if the greater proportion of these can be saved by being afforded a

permanent resting-place, it is clear that, by laying down a few thousand

breeders, we may, in the course of a year or two, have, at any place we

wish, a large and reproductive oyster-farm. With reference to the question

of growth, Coste tells us that stakes which had been fixed for a period of

thirty months in the lake of Fusaro were quite loaded with oysters when

they came to be removed. These were found to embrace a growth of three

seasons. Those of the first year's spawning were ready for the market ;

the second year's brood were a good deal smaller; whilst the remainder

were not larger than a lentil. To attain miraculous crops similar to those

once achieved in the Bay of St. Brieuc, or at the Ile de Re, little more

is required than to lay down the spawn in a nice rocky bay, or in a place

paved for the purpose, and having as little mud about it as possible. A

place having a good stream of water flowing into it is the most desirable,

so that the flock may procure food of a varied and nutritious kind. A

couple of hundred stakes driven into the soft places of the shore, between

high and low water mark, and these well supplied with branches held

together by galvanised iron wire (common rope might soon become rotten),

would, in conjunction with the rocky ground, afford capital holding-on

places, so that any quantity of spawn might, in time, be developed into

fine "natives." There are hundreds of places on the English and Irish

coasts where such farms could be advantageously laid down.

Since the previous editions of this

work were issued, bad news has been received about the French oyster

farms, many of them having become exhausted through the greed of their

proprietors, who at an early period began to kill the goose for the sake

of its golden egg, a calamity that seems to be too frequently an attendant

consequence of the present system of fishing economy. In the year 1863, as

far as I can ascertain, the artificial system culminated at the Ile de

Re, and since then the beds have yearly become less prolific.

A great amount of the miscellaneous

information regarding oyster-growth and oyster-commerce, which has been

circulated during the last five years, is not of a reliable nature ; but

many of the circumstances attendant on artificial culture are interesting,

and have been proved to be correct, although they seem contradictory : as,

for instance, that oysters if spawned on a muddy bottom are lost, although

the same muddy bottom is highly suitable for the feeding 'stages of the

mollusc. It is also remarkable that breeding oysters do not fatten, and

that fat oysters yield no spat. There has been some controversy as

to whether transplanted oysters will breed; opinions differ, and it is on

record that such a remarkable spat once fell on the Whitstable grounds as

to provide a stock for eleven years, including, of course; what was

gathered towards the end of that period. A close time for oysters is a law

of the land ; but for all that we might have-indeed, we have now-oysters

all the year round, because all oysters do not sicken or spat at

the same period; in fact the economy of fish growth is not yet understood

either by naturalists or fishermen; as an instance of mal-economy we have

salmon rivers closed at the very time they ought to be open, some rivers

being remarkable for early spawning fish, whilst others are equally so for

the tardiness with which their scaly inhabitants repeat the story of their

birth. In time, when we understand better how to manage our fisheries, the

supplies of all kinds of round and shell fish will doubtless be better

regulated than at present.

The following theory of the spat was

promulgated by the author through the columns of the Times:- " In

an open expanse of sea the spat may be carried to great distances by tidal

influence, or a sharp breeze upon the water may waft the oyster-seed many

a long mile away. Every bed has its own time of spatting thus, one

of a series of scalps may be spatting on a fine warm day, when the sea is

like glass, so that the spat cannot fail to fall; while on another portion

of the beds the spat may fall on a windy day, be thus left to the tender

mercy of a fiercely receding tide, and so be lost, or fall mayhap on

ungenial bottom a long way from the shore. On the Isle of Oleron, which

supplies the green oyster breeders of Marennes with such large quantities,

it is quite certain that in the course of the summer a friendly -wave

will waft large quantities of spat into the artificial pares, when it is

known that the oysters in these pares have not spawned. Where does this

foreign spat come from ? The men say it comes off some of the natural beds

of the adjoining sea-is driven in by the tide, and finds a welcome

resting-place on the artificial receivers of their pares. It is altogether

an erroneous idea to suppose that there are some seasons when the oyster

does not spat, because of the cold weather, etc. Some of the pares had

spatted at Arcachon this year [1866] in very ungenial weather. The

spatting of the oyster does not depend on the weather at all, but the

destination of the spat does, because if the tiny seedling oyster does not

fall on propitious ground it is lost for ever. New oyster-beds are often

discovered in places where it is certain oysters did not exist in previous

years. How came they then to be formed ? The spat must have been blown

upon that ground by the ill wind that carried it away from the spot where

it was expected to fall. If the spat exuded by the large quantity of

oysters known to be stocked in the pares at Whitstable, in Kent, the home

of the " native," were always to fall on the cultch of Whitstable, instead

of on the adjoining flats and elsewhere, the company would soon become

enormously wealthy. |