|

Difficulty of obtaining Statistics of our White-Fish Fisheries -

Ignorance of the Natural History of the White Fish - "Finnan Haddies" -

The Gadidae Family: the Cod, Whiting, etc. - The Turbot and other Flat

Fish - When Fish are in Season - How the White-Fish Fisheries are

carried on - The Cod and Haddock Fishery - Line-Fishing - The Scottish

Fishing Boats - Loss of Boats on the Scottish Coasts - Storms in

Scotland - Trawl-Net Fishing - Description of a Trawler - Evidence on

the Trawl Question.

How do we obtain our haddocks? Where

do we get our turbot? How comes it that all kinds of sea-fish are now so

dear? I propose briefly to answer these often-asked questions, and to

indulge at the same time in a little gossip about our larger sea-fishes,

so far as their economic history and value are concerned.

The two families which supply the

cod, haddock, turbot, sole, and other well-known table-fishes, such as the

whiting and flounder, are known to naturalists as

Gadidae and

Pleuronectidae—the

latter being the family of the flat fishes. Cod and turbot are of

considerable individual value, large prices being, at certain seasons of

the year, obtained for them; indeed, it is not long since the columns of

the Times recorded that a guinea had been given for a single

cod-fish; and as to haddocks and whitings, once so cheap, they are now, in

every sense of the word, dear, because, in addition to costing much money,

they are not so fine in quality as they used to be. At one time, in

various parts of both England and Scotland, a prime haddock, of say three

pounds weight, might have been purchased for about twopence; and a

cod-fish of great size could, in the days referred to, be purchased for

ninepence. Indeed, so near the present time as a quarter of a century ago,

all kinds of white fish were purchasable at less than a penny per pound

weight; and as for sprats and herrings, a large dish of the former could

be had for a half-penny, whilst,

"three a penny" was a common price for the finest fresh herrings. At

various times within the memory of the present generation, both sprats and

herrings have been so plentiful as to be sold for manure. Such days,

however, are gone, never to return. The railways, which have altered so

many conditions of life and trade, have changed entirely the whole system

of fish commerce. Thousands of tons of our best food fishes are now borne

daily from the sea to the great inland seats of population, where there is

a sure and speedy demand for as much as can be sent. The London

commissariat alone, supplemented by a few other large cities, demands, but

fortunately does not obtain, all the fish of the sea ! Haddocks, cod-fish,

whitings, and turbot, can be sold in any quantity when the price is

moderate ; but no person can exactly estimate the supply, as there is no

record kept at Billingsgate of the total business done there; nor is all

the fish business of London now transacted at Billingsgate, as many of the

West-end fishmongers obtain their supplies direct from the coast. We

should be glad if reliable statistics of the annual "take" of sea-fish

were collected by Government. Correct figures would be a guide as to the

supplies; we should then really know if our fish food was increasing or

diminishing. Such statistics are taken in Scotland as regards the herring,

and what is done for that fish might be (lone for other fishes. It is said

that there are at present a thousand trawlers employed for the London

market ; and if each of these vessels takes about one hundred tons of fish

per annum, we should find that nearly one hundred thousand tons of large

fish are taken every year, in addition to the abundant supplies of

herring, mackerel, sprats, etc., which are being constantly forwarded day

by day to the great metropolis.

The natural history of our white

fish is but imperfectly known. As an instance of the very limited

knowledge we possess of the natural history of even our most favourite

fishes, I may state that at a meeting of the British Association a few

years ago, a member who read an interesting paper On the Sea Fisheries

of Ireland, introduced specimens of a substance which the Irish

fishermen considered to be spawn of the turbot; stating that wherever this

substance was found trawling was forbidden ; the supposed spawn being in

reality a kind of sponge, with no other relation to fish except as being

indicative of beds of mollusca, the abundance of which marks that fish are

plentiful. It follows that the stoppage of trawling on the grounds where

this kind of squid is found is the result of sheer ignorance, and causes

the loss, in all likelihood, of great quantities of the best white fish.

It is not easy to say when the Gadidae are in proper season. Some of the

members of that family are used for table purposes all the year round ;

and as different salmon rivers have their different close-times, so

undoubtedly will the white fish of different seas or firths have different

spawning seasons. In reference, for instance, to so important a fish as

the turbot, we are very vaguely told by Yarrell that it spawns in

the spring-time, but no indication is given of the particular month in

which that important operation takes place, or how long the young fish

take to grow. Even a naturalist so well informed as the late Mr. Wilson

was of opinion that the turbot was a travelling fish, which migrated from

place to place.

The combined ignorance of

naturalists and fishermen has much to do with the scarcity of white fish

now beginning to be experienced ; and unless some plan be hit upon to

prevent overfishing, we may some fine morning experience the same

astonishment as a country gentleman's cook, who had given directions to

the gamekeeper to supply the kitchen regularly with a certain quantity of

grouse. For a number of years she found no lack, but in the end the

purveyor threw down the prescribed number, and told her she need look for

no more from him, for on that day the last grouse had been shot. "There

they are," said the gamekeeper, "and it has taken six of us, with a gun

apiece, to get them, and after all we have only achieved the labour which

was gone through by one man some years ago." The cook had unfortunately

never considered the relation between guns and grouse.

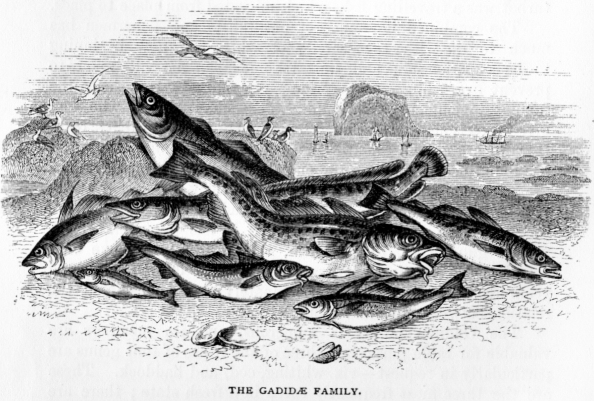

The Gadidae family is numerous, and

its members are valuable for table purposes ; three of the fishes of that

genus are particularly in request-viz. whiting, cod, and haddock. These

are the three most frequently eaten in a fresh state ; there are others of

the family which are extensively captured for the purpose of being dried

and salted, among which are the ling, the tusk, etc. The haddock (Morrhua

aylefinus) has ever been a favourite fish, and the quantities of it

which are annually consumed are really wonderful. Vast numbers used to be

taken in the Firth of Forth, but from recent inquiries at Newhaven I am

led to believe that the supply has considerably decreased of late years,

and that the local fishermen have to proceed to considerable distances in

order to procure any quantity.

In reference to the question, "Where

are the haddocks 4" asked on another page, it is right to say that this

prime fish has more than once become scarce. I have been reminded of a

time, in 1790, when three of these fish were sold for

7s. 6d. in

the Edinburgh market ; but although there have been from time to time

sudden disappearances of the haddock from particular fishing-grounds, as

indeed there have been of all fish, that is a different, a totally

different matter from what the fisher folk and the public have now to

complain of-viz, a yearly decreasing supply. I once took part in a

newspaper controversy about the scarcity of the haddock, and I found

plenty of opponents ready to maintain that there was no scarcity, but that

any quantity

could be captured. In some degree

that is the truth, but what is the hook-power required now to capture "

any quantity," and how long does it take to obtain a given number as

compared with former times, when that fish was supposed to be more

plentiful? Why do we require, for instance, to send to Norway and other

distant places for haddocks and other white fish 1 The only answer I can

imagine is that we cannot get enough at home. As to the general scarcity

of white fish, the late Mr. Methuen, the fish-curer, wrote some

few years ago:-" This morning I am told that an Edinburgh fishmonger has

bought all the cod brought into Newhaven at 5s. to 7s. each. I recollect when

I cured thousands of cod at 3d. and 4d. each ; they were caught between

Burntisland and Kincardine, on which ground not a cod is now to be got ;

and at the great cod emporium of Cellardyke, the cod fishing, instead of

threescore for a boat's fishing, has dwindled down to about half-a-dozen

cod."

The old belief in the migratory

habits of fish comes again into notice in connection with the haddock.

Pennant having taught us that the haddock appeared periodically in great

quantities about mid-winter, that theory is still believed, although the

appearance of this fish in shoals may be easily explained, from the local

habits of most of the denizens of the great deep. It is said that "in

stormy weather the haddock refuses every kind of bait, and seeks refuge

among marine plants in the deepest parts of the ocean, where it remains

until the violence of the elements is somewhat subsided." This fish does

not grow to any great size; it usually averages about five pounds. I

prefer it as a table fish to the cod. The very best haddocks are taken on

the coast of Ireland. The scarcity of fresh haddocks may in some degree be

accounted for by the immense quantities which are converted into "Finnan

haddies" - a well-known breakfast luxury no longer confined to Scotland.

It is difficult to procure genuine Finnans, smoked in the original way by

means of peat-reek; like everything else for which there is a great

demand, Finnan haddocks are now " manufactured " in quantity ; and, to

make the trade a profitable one, they are cured by the hundred in

smoking-houses built for the purpose, and are smoked by burning wood or

sawdust, which, however, does not give them the proper gout. In

fact the wood-smoked Finnans, except that they are fish, have no more the

right flavour than Scotch marmalade would have were it manufactured from

turnips instead of bitter oranges. Fifty years ago it was different ; then

the haddocks were smoked in small quantities in the fishing villages

between Aberdeen and Stonehaven, and entirely over a peat fire. The

peat-reek imparted to them that peculiar flavour which gained them a

reputation. The fisher-wives along the north-east coast used to pack small

quantities of these delicately-cured fish into a basket, and give them to

the guard of the "Defiance" coach, which ran between Aberdeen and

Edinburgh, and the guard brought them to town, confiding them for sale to

a brother who dealt in provisions ; and it is known that out of the

various transactions which thus arose, individually small though they must

have been, the two made, in the course of time, a handsome profit. The

fame of the smoked fish rapidly spread, so that cargoes used to be brought

by steamboat, and Finnans are now carried by railway to all parts of the

country with great celerity, the demand being so great as to induce men to

foist on the public any kind of cure they can manage to accomplish ;

indeed smoked codlings are extensively sold for Finnan haddocks. Genuine

smoked haddocks of the Moray Firth or Aberdeen cure can seldom now be had,

even in Edinburgh, under the price of sixpence per pound weight.

The common cod

(Morrhua vulgaris) is, as the

name implies, one of our best-known fishes, and it was at one time very

plentiful and cheap. It is found in the deep waters of all our northern

seas, but has never been known in the Mediterranean. It has been largely

captured on the coasts of Scotland, and, as is elsewhere mentioned, it

occurs in profusion on the shores of Newfoundland, where its plentifulness

led to a great fishery being established. The cod is extremely voracious,

and eats up most greedily the smaller inhabitants of the seas; it grows to

a large size, and is very prolific in the perpetuation of its kind. A

cod-roe has more than once been found to be half the gross weight of the

fish, and specimens of the female have been caught with upwards of three

millions of eggs ; but of course it cannot be expected that in the great

waste of waters all the ova will be fertilised, or that any but a small

percentage of the fish can ever arrive at maturity. This fish spawns in

mid-winter, but there are no very reliable data to show when it becomes

reproductive. My own opinion has already been expressed that the cod is an

animal of slow growth, and I would venture to say that it is at least

three years old before it is endowed with any breeding power. I may call

attention here to one of the causes that must tend to render the fish

scarce. As if the natural enemies of the young fish were not sufficient to

aid in its extirpation, and the loss of the ova from causes over which man

has no control not enough in the way of destruction, there is a commerce

in cod-roe, and enormous quantities of it, as I have mentioned in the

preceding chapter, are used in France as ground-bait for the sardine

fishery ! The roe of this fish is also frequently made use of at table ; a

cod-roe of from two to four pounds in weight can unfortunately be bought

for a mere trifle, but it ought to cost a good few pounds instead of a few

pence. I have elsewhere stated that the quantity of eggs yielded by a

female cod is often three millions : supposing only a third of them to

come to life-that is one million-and that a tenth part of that number,

viz. one hundred thousand, becomes in some shape-that is, either as

codling or cod-fit for table uses, what should be the value of the cod-roe

that is carelessly consumed at table ? If each fish be taken as of the

value of sixpence, the amount would be £2500. But supposing that

only twenty full-grown codfish resulted from the three millions of

eggs ; these, at two and sixpence each, would represent the sum of fifty

shillings as the possible produce of one dish, which, in the shape of

cod-roe, cost only about as many farthings !

Cuvier tells us that

"almost all the parts of the cod are adapted for the nourishment of man

and animals, or for some other purposes of domestic economy. The tongue,

for instance, whether fresh or salted, is a great delicacy ; the gills are

carefully preserved, to be employed as baits in fishing ; the liver, which

is large and good for eating, also furnishes an enormous quantity of oil,

which is an excellent substitute for that of the whale, and applicable to

all the same purposes ; the swimming-bladder furnishes an isinglass not

inferior to that yielded by the sturgeon; the head, in the places where

the cod is taken, supplies the fishermen and their families with food. The

Norwegians give it with marine plants to their cows, for the purpose of

producing a greater proportion of milk. The vertebrae, the ribs, and the

bones in general, are given to their cattle by the Icelanders, and by the

Kamtschatkians to their dogs. These same parts, properly dried, are also

employed as fuel in the desolate steppes of the shores of the Icy Sea.

Even their intestines and their eggs contribute to the luxury of the

table." I may just mention another most useful product of the codfish.

Cod-liver oil is now well known in materia medica under the name of

oleum jecoris aselli. The

best is made without boiling, by applying to the livers a slight degree of

heat, straining through thin flannel or similar texture. When carefully

prepared it is quite pure, nearly inodorous, and of a crystalline

transparency. The specific gravity at temperature 64º is about

920º. It seems to have been first used medicinally by Dr.

Percival in 1782 for the cure of chronic rheumatism ; afterwards by Dr.

Bardsly in 1807. It has now become a popular remedy in all the

slow-wasting diseases, particularly in scrofulous affections of the joints

and bones, and in consumption of the lungs. The result of an extended

trial of this medicine in the hospital at London for the treatment of

consumptive patients shows that about 70 per cent gain strength and

weight, and improve in health, while taking the cod-liver oil; and this

good effect with a great many is permanent. Skate-liver oil is likewise

coming into use for medicinal purposes, and I have no doubt that the oil

obtained from some of our other fishes will one day be found useful in a

medicinal point of view.

The codfish is best when eaten

fresh, but vast quantities are sent to market in a dried or cured state :

the great seat of the cod-fishery for curing purposes is at Newfoundland.

But considerable numbers of cod and ling are likewise cured on the coasts

of Scotland. The mode of cure is quite simple. The fish must be cured as

soon as possible after it has been caught. A few having been brought on

shore, they are at once split up from head to tail, and by copious

washings thoroughly cleansed from all particles of blood. A piece of the

backbone being cut away, they are then drained, and afterwards laid down

in long vats, covered with salt, heavy weights being placed upon them to

keep them thoroughly under the action of the pickle. By and by the fish

are taken out of the vat, and are once more drained. being at the same

time carefully washed and brushed to prevent the collection of any kind of

impurity. Next the fish are pined by exposure to the sun and air; in other

words, they are bleached by being spread out individually on the sandy

beach, or upon such rocks or stones as may be convenient. After this

process has been gone through the fish are then collected into little

heaps, which are technically called steeples. When the bloom,

or whitish appearance which after a time they assume, comes out on the

dried fish the process is finished, and they are then quite ready for

market. The consumption of dried cod or ling is very large, and extends

over the whole globe ; vast quantities are prepared for the religious

communities of Continental Europe, who make use of it on the fast-days

instituted by the Roman Catholic Church.

Besides the common cod, there are

the dorse (M. calories), and the poor or power cod (M, minuta),

also the bib or pout (M. lusca).

The whiting (Merlangus vulgaris)

is another of our delicious table-fishes, which is found in

comparative plenty on the British coasts. This fish is by some thought to

be superior to all the other Gadidae. Very little is known of its natural

history. It deposits its spawn in March, and the eggs are not long in

hatching-about forty days, I think, varying, however, with the temperature

of the season. Before and after shedding its milt or roe the whiting is

out of condition, and should not be taken for a couple of months. The

whiting prefers a sandy bottom, and is usually found a few miles from the

shore, its food being much the same as that of other fishes of the family

to which it belongs. It is a smallish fish, usually about twelve inches

long, and on the average two pounds in weight.

I need scarcely refer to the other

members of the Gadidae: they are numerous and useful, but, generally

speaking, their characteristics are common and have been sufficiently

detailed. [A correspondent has favoured me with the following brief

account of the sillock-fishing as carried on

in Shetland :-" Sillocks are the young of the saith, and they make their

appearance in the beginning of August about the small isles, and are of

the size of parrs in Tweed. They continue about said isles for a few

weeks, and in the months of September and October, and sometimes longer,

they hover about the small isles, when the fishermen catch them for the

sake of their liver, which contains oil. One boat of twelve feet of keel

will sometimes catch as many as thirty bushels in a part of a day, and

this year (1864), owing to the high price of oil, each bushel was

worth about Is. 6d. The fish itself is taken to the dunghill when the take

is not great, but when there is a great take the liver is taken out and

the fish thrown into the sea. There are no Acts of Parliament against

using the net ; but after some time the sillocks leave the isles and draw

to the shore, where there are any edge-places. It is allowed that the

island of Whalsey is about the best place in Shetland for the fish to draw

to, but whenever they come there, the proprieter, Mr. Bruce, will not

allow " pocking," as a week would finish them all ; but the people must

all fish with the rod, so that each man may get as many as keep him a day

or two. The "pocking" sets them all out, but the fish don't mind the rod ;

it is very picturesque to see perhaps fifty men sitting round the basin

with their rods, and the sillocks covering about a rood of the sea,

varying from three to six feet deep, and so close together that you would

think they could not get room to stir. They will continue plentiful till

the end of April, at which time they take to the deep sea ; and when they

make their appearance the following year they are about four times larger,

and are then called piltocks. But these are only taken by the rod. Air.

Bruce just says, If you pock, you cannot be my tenant ; so they must

either give up the one or the other, and by that way of doing every

household has as many of these small fish as they can make use of during

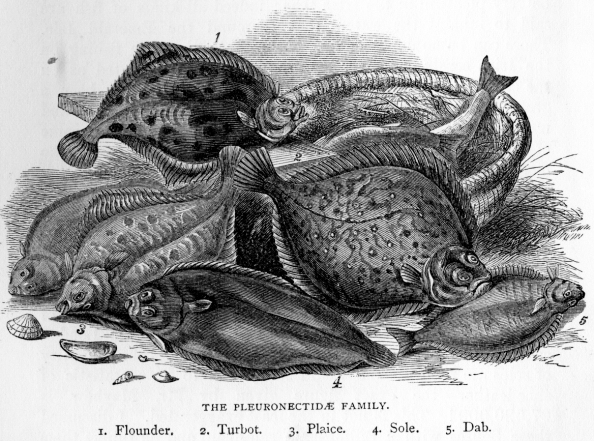

the winter," ] I will now, therefore, say a few words about the

Pleuronectidae. There are upwards of a dozen kinds of flat fish that are

popular for table purposes. One of these is a very large fish known as the

holibut (Hippoglopus vulgaris), which has been found in the

northern seas to attain occasionally a weight of from three to four

hundred pounds. One of this species of fish of extraordinary size was

brought to the Edinburgh market in April 1828 ; it was seven feet and a

half long, and upwards of three feet broad, and it weighed three hundred

and twenty pounds ! The flavour of the holibut is not very delicate,

although it has been frequently mistaken for turbot by those not

conversant with fish history.

The true turbot

(Rhombus maximus)

is the especial delight of aldermanic epicures, and

fabulous sums are said to have been given at different times by rich

persons in order to secure a turbot for their dinner-table. This fine fish

is, or rather used to be, largely taken on our own coasts ; but now we

have to rely upon more distant fishing-grounds for a large portion of our

supply. The old complaint of our ignorance of fish habits must be again

reiterated here, for it is not long since it was supposed that the turbot

was a migratory fish that might be caught at one place to-day and at

another to-morrow. The late Mr. Wilson, who ought to have known better,

said, in writing about this fish:-" The English markets are largely

supplied from the various sandbanks which lie between our eastern coasts

and Holland. The Dutch turbot-fishery begins about the end of March, a few

leagues to the south of Schevening. The fish

proceed

northwards as the season advances, and in April and May are found in great

shoals upon the banks called the Broad Forties. Early in June they

surround the island of Heligoland, where the fishery continues to the

middle of August, and then terminates for the year. At the beginning of

the season the trawl-net is chiefly used; but on the occurrence of warm

weather the fish retire to deeper water, and to banks of rougher ground,

where the long line is indispensable."

The turbot was well known in ancient

gastronomy ; the luxurious Italians used it extensively, and christened it

the sea-pheasant from its fine flavour. In the gastronomic days of ancient

Rome the wealthy patricians were very extravagant in the use of all kinds

of fish ; so much so that it was said by a satirist that

" Great turbots and the soup-dish led

To shame at last and want of bread."

The turbot is very common on the

English and Scottish coasts, and is known also on the shores of Greece and

Italy. This fish is taken chiefly by means of the trawl-net, but in some

places it is fished for by well-baited lines. We derive large quantities

of our turbot from Holland, so much as £100,000 having been paid to the

Dutch in one year for the quantities of these fish which were brought to

London, and on which, at one time, a duty of X6 per boat was exigible.

This fish spawns during the autumn, and is in fine condition for table use

during the spring and early summer. Yarrell says the turbot spawns in the

spring; ; but, with due respect, I think he is wrong ; I would not,

however, be positive about this, for there will no

doubt be individuals of the turbot

kind, as there are of all other kinds, that will spawn all the year round.

The turbot is a great flat fish. In Scotland, from its shape, it is called

" the bannock fluke." It is about twenty inches long, and broad in

proportion ; and a prime fish of this species will weigh from eight to

twelve pounds.

The best-known fish of the

Pleuronectidae is the sole (Solea

vulgaris), which is largely distributed in

all our seas, and used in immense quantities in London and elsewhere. The

sole is too well known to require any description at my hands. It is

caught by means of the trawl-net, and is in good season for a great number

of months. Soles of a moderate weight are best for the table. I prefer

such as weigh from three to five pounds per pair. I have been told, by

those who ought to know best, that the deeper the water from which it is

taken the better the sole. It is quite a ground fish, and inhabits the

sandy places round the coast, feeding on minor crustaceans, and on the

spawn and young of various kinds of fish. Good supplies of this popular

fish are taken on the west coast of England, and they are said to be very

plentiful in the Irish seas; indeed all kinds of fish are said to inhabit

the waters that surround the Emerald Isle. There can be no doubt of this,

at any rate, that the fishing on the Irish coasts has never been so

vigorously prosecuted as on the coasts of Scotland and England - so that

there has been a greater chance for the best kinds of white fish to thrive

and multiply. Seaside visitors would do well to go on board some of the

trawlers and observe the mode of capture. There is no more interesting way

of passing a seaside holiday than to watch or take a slight share in the

industry of the neighbourhood where one may be located.

The smaller varieties of the flat fish-such as Muller's

topknot, the flounder, whiff, dab, plaice, etc. - I need not particularly

notice, except to say that immense quantities of them are annually

consumed in London and other cities. Mr. Mayhew, in some of his

investigations, found out that upwards of 33,000,000 of plaice were

annually required to aid the London commissariat ! But that is nothing.

Three times that quantity of soles are needed-one would fancy this to be a

statistic of shoe-leather-the exact figure given by Mr. Mayhew is

97,520,000 ! This is not in the least exaggerated. I discussed these

figures with a Billingsgate salesman, and he thinks them quite within the

mark.

I have already alluded to the natural history of the

mackerel, and shall now say a word or two about the fishery, which is

keenly prosecuted. The great point in mackerel-fishing is to get the fish

into the market in its freshest state ; and to achieve this several boats

will join in the fishery, and one of their number will come into harbour

as speedily as possible with the united take. The mackerel is caught in

England chiefly by means of the seine-net, and much in the same way as the

pilchard. A great number of this fish are however captured by means of

wellbaited lines, and in some places a drift-net is used. Any kind of bait

almost will do for the mackerel-hooks-a bit of red cloth, a slice of one

of its own kind, or any clear shiny substance. Mackerel are not quite so

plentiful as they used to be.

As to when the Gadidae and other white fish are in

their proper season it is difficult to say. Their times of sickness are

not so marked as to prevent many of the varieties from being used all the

year round. Different countries must have different seasons. We know, for

instance, that it is proper to have the close-time of one salmon river at

a different date from that of some other stream that. may be farther south

or farther north ; and I may state here, that during several winter visits

which I made to the Tay, beautiful clean salmon were running in December.

There are also exceptional spawning seasons in the case of individual

fish, so that we are quite safe in affirming that the sole and turbot are

in season all the year round.

There is no organisation in Scotland for carrying on

the white fisheries, as there is in the case of the oyster or herring

fisheries. So far as our most plentiful table fish are concerned, the

supply seems utterly dependent on chance or the will of individuals. A man

(or company) owning a boat goes to sea just when he pleases. In Scotland,

where a great quantity of the best white fish are caught, this is

particularly the case, and the consequence is that at the season of the

year when the principal white and flat fish are in their primest

condition, they are not to be procured ; the general answer to all

inquiries as to the scarcity being, "The men are away at the herring."

This is true ; the best boats and the strongest and most intelligent

fishermen have removed for a time to distant fishing-towns to engage in

the capture of the herring, which forms, during the summer months, a noted

industrial feature on the coasts of Scotland, and allures to the scene all

the best fishermen, in the hope that they may gain a prize in the great

herring lottery, prizes in which are not uncommon, as some boats will take

fish to the extent of two hundred barrels in the course of a week or two.

Only a few decrepit old men are left to try their luck with the cod and

haddock lines ; the result being, as I have stated above, a scarcity of

white and flat fish, which is beginning to be felt in greatly enhanced

prices. An intelligent Newhaven fishwife recently informed me that the

price of white fish in Edinburgh - a city close to the sea - has been more

than quadrupled within the last thirty years. She remembers when the

primest haddocks were sold at about one penny per pound weight, and in her

time herrings have been so plentiful that no person would purchase them.

We shall not soon look again on such times.

The cod and haddock fishery is a laborious occupation.

At Buckie, a quaint fishing -town on the Moray Firth, it is one of the

staple occupations of the people. At that little port there are generally

about thirty or forty large boats engaged in the fishery, as well as a

number of smaller craft used to fish inshore. These boats, which measure

from thirty to forty feet, are, with the necessary hooks and lines, of the

value of about £100. Each boat is generally the property of a joint-stock

company, and has a crew of eight or nine individuals, who all claim an

equal share in the fish captured. The Buckie men often go a long distance,

forty or fifty miles, to a populous fishing-place, and are absent from

home for a period of fifteen or twenty hours. At many of the fishing

villages from which herring or cod boats depart, there is no proper

harbour, and at such places the sight of the departing fleet is a most

animated one, as all hands, women included, have to lend their aid in

order to expedite the launching of the little fleet, as the men who are to

fish must be kept dry and comfortable. Even at places where there is a

harbour, it is often not used, many of the boats being drawn up for

convenience on what is called the boat-shore. At Cockenzie, near

Edinburgh, several of the boats are still drawn up in this rude way, and

the women not only assist in launching and drawing up the boats, but they

sell the produce taken by each crew by auction to the highest bidder -the

purchasers usually being buyers of speculation, who send the fish by train

to Edinburgh, Manchester, or London.

From the little ports of the Moray Firth, the men, as I

have said, have to go long distances to fish for cod and ling. As they

have none but open boats, it will easily be understood that they live hard

upon such occasions. They are sometimes absent from home for about a week

at a stretch, and as the weather is often very inclement the men suffer

severely. The fish are not so easily procured as in former years, so that

the remuneration for the labour undergone is totally inadequate. A large

traffic in living codfish used to be carried on from Scotland; quick

vessels furnished with wells took the cod alive as far as Gravesend,

whence they were sent on to London as required.

I cannot say much about the white-fish fisheries of

Ireland from personal knowledge, but the latest report of the Irish

fishery inspectors contains some interesting information on the subject

which I have abridged for the benefit of my readers. I glean from it that

the Irish fisheries are at present in a somewhat sensational position, and

have of late attracted more than usual attention. The reason of this is

their rapid decline-a decline which dates from the beginning of the Irish

famine in 1846. At that period nearly 20,000 boats or other vessels of

various sizes were engaged in the Irish fisheries, manned by over 100,000

men and boys. Last year [1872] the number of vessels and boats was under

8000, and the men and boys taking part in the fisheries numbered a little

over 31,000, being a decrease as compared with the previous year [1871]

of, in round numbers 1000 boats and 7000 men.

Statistics of the Irish sea fisheries are annually

collected by members of the Coastguard, who fill up schedules supplied by

the inspectors, which seem one year with another to be consistent and

reliable ; but in addition to the matter collected by the Coastguardsmen,

much interesting information about the Irish fisheries and the decline of

co-operative fishing has been interpolated by the inspectors, who, in one

paragraph of their present report, confirm to some extent an opinion which

is held by some earnest inquirers, to the effect that in Ireland, as in

Scotland and England, the fishermen find it necessary to go farther afield

for their supplies, there being a considerable falling-off in the

productiveness of the inshore fisheries compared with the quantities of

fish obtained about thirty years ago. In consequence of this many fishers

with imperfect or weak fishing gear have been obliged to give up fishing,

not daring to venture to sea with old patched-up boats and ragged netting

imperfectly protected from the action of the waves because of a deficient

supply of catechu with which to dye or "bark" their nets and sails.

Other two of the numerous fishing companies started in

Ireland were last year compelled to haul down their flag; these were the

"South of Ireland Fishing Company," which for some years carried on

operations at Kinsale so far as its chief business was concerned, but

which lately engaged in the herring fishery prosecuted off Howth; and the

small "Limited" company known as the "Inishbofin Fishing Company." There

is now, properly speaking, no joint-stock fishing company in Ireland. The

boats and gear of the South of Ireland Company were purchased chased by

two or three private individuals, and other undertakings of a

semi-joint-stock kind have generally not more than three partners. As

regards the numerous fishing companies started from time to time in

Ireland, the inspectors tell us that they have in the end been obliged to

be wound up with great loss to their shareholders. On the other hand,

while the large companies have all been obliged to succumb to the force of

circumstances, smaller enterprises entered into by practical men having a

thorough knowledge of the art of fishing and of the best markets in which

to sell their fish, have usually proved successful; and, as a proof of

this averment, the inspectors point to the boats belonging to Dublin, and

three or four small enterprises now in most successful operation at

Dunmore, in the county of Waterford.

As one mode of arriving at the value, or at least the

quantity, of the fish taken in Ireland, the returns of the weight carried

on the various lines of railway are given, which the Commissioners might

annually summarise for comparison with preceding years. The following is a

summary of the tonnage for 1872 :-Carried on railways, 5658 tons 11 cwt. ;

taken away by steamers, 3974 tons 18 cwt. ; total, 9633 tons 9 cwt.

But it is not explained by the inspectors whether any portion or how much

of the fish taken away by steamboats to Scotland and England is included

in the quantity sent by railway. Taking it for granted, however, that the

steamboat portion was sent direct from the ports of capture, the weight of

fish carried, reduced to pounds would be 21,578,928, which, at an average

(wholesale price) of 3d. per pound - a considerable portion of the fish

being salmon-would yield £269,736 :12s.

The vexed question of loans to the Irish fishermen is

more directly illustrated in the present report than it was in that of

1871. It was said then by the inspectors that if the same Imperial aid had

been afforded to the Irish fisheries as has for years been extended to the

Scottish fisheries, and if the landed proprietary on the Irish coast had

taken as much interest in fishing as the Scottish gentry, the Irish

fisheries of to-day would present a very different picture from the

melancholy decay of that industry which is rapidly going on over fully

two-thirds of the Irish coast-line. They attribute the highly prosperous

condition of the Scottish fisheries in a great measure to the generous

assistance which for many years has been extended to them by the Imperial

Exchequer. The Inspecting Commanders of the Irish Coastguard have so

frequently reported on the loan question that the Inspectors of Irish

Fisheries did not think this year of repeating their queries, but an

analysis of the replies received in 1870-71 from the thirty divisions of

the coast showed that in twenty loans would be beneficial, that security

could be obtained in eight, that security would be doubtful in eleven,

that it could not be obtained in one, that loans would not benefit the

fishermen in six of the districts, and that the benefit would be doubtful

in three. From one of the districts a return was not obtained. "It is

singular," say the inspectors, "that in some of the divisions in which the

Coastguard officers report that security would be doubtful, or loans not

likely to prove beneficial, the Society for Bettering the Condition of the

Poor of Ireland has made large advances without loss, and the fishermen

have been much benefited."

Prolific as our coast fisheries have been, and still

are, comparatively speaking, the North Sea is at present the grand

reservoir from which we obtain our white fish. Indeed, it has been the

great fish-preserve of the surrounding peoples since ever there was a

demand for this kind of food. All the bestknown fishing banks are to be

found in the German Ocean - Faroe, Loffoden, Shetland, and others nearer

home - and its waters, filling up an area of 140,000 square miles, teem

with the best kinds of fish, and give employment to thousands of people,

as well in their capture and cure as in the building of the ships, and the

development of the commerce which is incidental to all large enterprise.

It will doubtless be interesting to my readers to know

something about the general machinery of fish-capture, so far as regards

the British sea-fisheries. The modern cod-smack, clipper-built for speed,

with large wells for carrying her live fish, costs £1500. She usually

carries from nine to' eleven men and boys, including the captain. Her

average expense per week is £20 during the long-line season in the North

Sea; but it exceeds this much if unfortunate in losing lines. Fishing has

of late been a most uncertain venture. The line is chiefly used for the

purpose of taking cod and haddock. The number of lines taken to sea in an

open boat depends upon the number of men belonging to the particular

vessel. Each man has a line of 50 fathoms (300 feet) in length; and

attached to each of these lines are 100 "snoods," with hooks already

baited with mussels, pieces of herring or whiting. Each line is laid

"clear" in a shallow basket or "scull " - that is, it is so arranged as to

run freely as the boat shoots ahead. The 50-fathom line, with 100 hooks,

is in Scotland termed a" taes." If there are eight men in a boat the

length of line will be 400 fathoms (2400 feet), with 800 hooks (the lines

being tied to each other before setting). On arriving at the

fishing-ground the fishermen heave overboard a cork buoy, with a

flag-staff fixed to it about six feet in height. The buoy is kept

stationary by a line, called the "powend," reaching to the bottom of the

water, and having a stone or small anchor fastened to the lower end. To

the powend is also fastened the fishing-line, which is then "paid" out as

fast as the boat sails, which may be from four to five knots an hour.

Should the wind be unfavourable for the direction in which the crew wish

to set the line they use the oars. When the line or taes is all out the

end is dropped, and the boat returns to the buoy. The pow-end is hauled up

with the anchor and fishing-line attached to it. The fishermen then haul

in the line with whatever fish may be on it. Eight hundred fish might be

taken (and often have been) by eight men in a few hours by this operation

; but many fishermen now say that they consider themselves very fortunate

when they get a fish on every five hooks on an eight-taes line. Many a

time too the fish are all eaten off the line by "dogs" and other enemies,

so that only a few fragments and a skeleton or two remain to show that

fish have been caught. The fishermen of deck-welled cod-bangers use both

hand-lines and long-lines such as have been described. The cod-bangers'

tackling is of course stronger than that used in open boats. The

long-lines are called "grut-lines," or great-lines. Every deck-welled

cod-banger carries a small boat on deck for working the great-lines in

moderate weather. As soon as the cod and haddock are taken off the hooks

they are put into a "well," formed by a part of the smack's hold, divided

from the rest of the vessel by water-tight bulkheads. The well occupies

the whole breadth of the vessel, and the sea has free access to it through

auger holes bored in the sides and bottom of that part of the smack. When

the well has been sufficiently stored, the vessel returns to port with her

cargo of live fish, which are then transferred to chests, in which they

are kept afloat, and in good order, till wanted for market. Some hundreds

of these cod, according to the demand, are taken out of the chests every

afternoon, and after being killed by one or two blows on the head, are

sent by train to Billingsgate and other markets, where they are sold as

"live cod," and fetch the highest price given for that kind of fish.

Haddocks are stored and treated in a similar manner, but the supply of

line-caught haddocks is trifling compared with what is provided by the

trawlers. Some cod-fish are still brought home alive in welled vessels, in

the way described, whilst others of the fish are crimped. They are first

of all stunned by a blow when they are caught, and then laid down in

cases, from which they are only removed in order to be crimped.

Hungry codfish will seize any kind of bait, and

great-lines are usually baited with bits of whiting, herring, haddock, or

almost any kind of fish. For hand-lines the fishermen prefer mussels or

white whelks. White whelks are caught by a line on which is fastened a

number of pieces of carrion or cod-heads. This line is laid along the

bottom where whelks are known to abound. The whelks attach themselves to

the cod-heads, and are pulled up, put into net bags, something like

onion-nets, and placed in the well of the vessel, where they are kept

alive till required for use. Another kind of bait used by the boat

fishermen for hand-lines is that of the lug-worm. The "lug" is a

sand-worm, from four to five inches long, and about the thickness of a

man's finger. The head part of the worm is of a dark brown fleshy

substance, and is the part used as bait, the rest of the worm being

nothing but sand. The " lug " is dug from the sand with a small spade or

three-pronged fork.

The principal fishing-grounds in the North Sea where

cod-bangers are employed are the Dogger Bank, Well Bank, and Dutch Bank.

The fishing-ground of the open boat fishermen is on the coasts of Fife,

Midlothian, and Berwickshire; for haddocks, cod, ling, etc., it is around

the island of May and the Bell Rock, Marrbank, Murray Bank, and Montrose

Pits, etc.

Some of the fishes of the Gadidae are

extensively cured, as the ling and hake, large numbers of which are

captured to be bleached both for the home and foreign markets. Spain

obtains a great quantity of its cured fish from the Shetland Islands,

where a cod and ling fishery is carried on pretty nearly all the year

round, there being both a winter and a summer fishery. In the summer time

the fishermen proceed with their boats to the smaller islands, where they

encamp in little huts for a few days, in order to carry on their business.

They generally remain out from Monday till Saturday, when they return home

to spend the day of rest with their families. As a general rule, the men

are very pious, and make it a point of honour to be at home on "the Lord's

day."

There has been a large amount of exaggeration as to the

injury done to the white-fish fishery by the trawls. Fishermen who have

neither the capital nor the enterprise to engage in trawling themselves

are sure to abuse those who do; but the trawl is so formidable as to have

induced various French writers to advocate its prohibition. They describe

this instrument of the fishery as terrible in its effects, leaving, when

it is used, deep furrows in the bottom of the sea, and crushing alike the

fry and the spawn; but there is a very evident exaggeration in this

charge, because as a general rule the beam-trawl cannot be worked with

safety except on a sandy or muddy bottom, and, so far as we know, fish

prefer to spawn on ground that is slightly rocky or weedy, so that the

spawn may have something to adhere to, which it evidently requires in

order to escape destruction; and when a quantity of spawn is discerned on

a bit of sea-weed or rock, we always find that, from some viscid property

of which it is possessed, it adheres to its resting-place with great

tenacity. The trawl-net, however destructive its agency, cannot, I fear,

be dispensed with; and, used at proper seasons and at proper places, is

the best engine of capture we can have for the kinds of fish which it is

employed to secure. The trawl is very largely used by English fishermen,

but it is only of late years that the trawlers have come so far north as

Sunderland and Berwick, and it is the fishermen of these places who have

got up the cry about that net being so injurious to the fisheries. In

Scotland there are no resident trawlers, the fisheries being chiefly of

the nature of a coasting industry, where the men, as a general rule, only

go out to sea for a few hours and then return with their capture. Having

been frequently on board of the trawling ships, I may perhaps be allowed

to set down a few figures indicative of the power of the great beam-net.

A trawler, then, is a vessel of about 35 tons burden,

and usually carries 7 persons—viz. 5 men and 2 apprentices—as a

crew to work her.

[A Barking trawler usually carries 5 men and 3 boys,

and costs when in full work £12 per week. A Hull trawler costs much less,

and the owner has less risk ; because the crew, from the captain

downwards, share in the catch. The Barking men refuse to enter into this

arrange. ment, which probably helps to account for the decay of the

Barking fishery, for that of Hull is comparatively prosperous. The

co-operative system prevails among a few of the fisher people of England.

In an account of a Yorkshire fishing-place recently published in Once a

Wee/c, the following statistics of the cost of boats, etc., are given

:—

"Each yawl, varying in tonnage from 28 to 45 tons,

costs from £600 to £650, and is divided into shares; of its earnings 3s.

6d. in the pouud are paid to the owner or owners, 10s. are devoted to the

current expenses, and the remainder is divided among the nien who find the

bait. When a new boat is required, several persons—gentlemen speculators,

harbour-masters, etc., and boatmen—take certain shares of it, which vary

in amount from a half-quarter to a half of the cost; application is then

made to a builder, sail-maker, anchor-maker, and other tradesmen ; and the

vessel, in due time, is paid for, equipped, and given over to the owners.

Each logger-yawl carries two masts and is provided with three sets of

sails to suit various states of weather. The foresail contains 200 or 250

yards, the mizen 100, and the mizen-topsail 40 yards ; the lesser sizes

being severally of 100, 60, and 50 yards. The jib is very small. On the

average the yawl is of 40 tons, and measures 51 feet keel, or 55 feet over

all, and is of 17 or 18 feet beam ; drawing 6 1/2 feet water aft, and 5

feet forward. The amount of ballast varies from 20 to 30 tons; The yawl is

provided with 120 nets, each of which costs £30. Half of this number are

left on shore, and changed at the end of every 12 weeks. The crew is

composed of 7 men and 2 boys. For instance, the "Wear," commanded by

Colling, a first-rate seaman, carries two others, like himself

part-owners, 4 men receiving, besides their food, £1, and 1 boy at 18s.,

and another at 11s, a week ; each fisherman, who is a net-owner, receives

24s. a week. The expenses in wages and wear and tear are calculated at

from £12 to £15 weekly. The herrings are valued at £2 per 1000 on an

average. Sometimes 23,000 fish are caught in a single haul, occasionally

as many as 60,000, but 40,000 are considered a good catch. To remunerate

the crew, or £60 a week ought to be obtained. Each net is 10 fathoms long,

and is sunk 9 fathoms during the fishing, the upper part being floated by

a long series of barrels, which are fitted at intervals of 15 fathoms. The

warps used for laying out the nets in each vessel measure 2200 yards. Two

men take up the nets, two empty the fish out of them, and one boy stows

the nets while his fellow stows the warps, which are raised by a windlass

worked by the men. Each net weighs about 28 pounds. In order to preserve

the nets and sails, it is necessary at frequent intervals to cover

them with tanning, which is prepared in large coppers These coppers cost

£40."

On the Gulf of St. Lawrence the engagements of fishermen are as follows

:—

"The fishermen are brought to the fishing-station at

the expense of the firm engaging them. They are furnished with a good

fishing-boat, thoroughly fitted, and are besides supplied with fresh bait

as long as it can be got, and they require it, but on payment of a sum of

$6 to $8; and for each 100 codfish delivered on the stage they receive the

sum of 5s. 6d., one half in money and the other half in goods and

provisions. At these prices, and fish being abundant, fishermen earn $5,

$10, $15, and even $20 a day; and after an absence of from 6 to 9 weeks,

bring home from $80 to $120, and sometimes more. But they have to board

themselves ; and if the fish is not abundant, their account of the

provisions lent to their families before their departure, their own board,

the purchase of their lines, take up the greatest part of their earnings,

and they very often return to Magdalen Islands with empty pockets." Great

quantities of all kinds of fish are found in the St. Lawrence.]

The trawl-rope is 120 fathoms in length and 6 inches in

circumference, and to this rope are attached the different parts of the

trawling apparatus—viz, the beam, the trawl-heads, bag-net, ground-rope,

and span or bridle. The trawler is furnished with a capstan for hauling in

this heavy machine. The beam, a spar of heavy elm wood, is 38 feet in

length and 2 feet in circumference at the middle, and is made to taper to

the ends. Two trawl-heads (oval rings, 4 feet by 2 1/2 feet) are fixed to

the beam, one at each end. The upper part of the bag-net, which is about

100 feet long, is fastened to the beam, while the lower part is attached

to the ground-rope. The ends of the ground-rope are fastened to the

trawl-beds, and being quite slack, the mouth of the bag-net forms a

semicircle when dragged over the ground. The whole apparatus is fastened

to the trawl-rope by means of the span or bridle, which is a rope double

the length of the beam, and of a thickness equal to the trawl-rope. Each

end of the span is fastened to the beam, and to the loop thus formed the

trawl-rope is attached. The ground-rope is usually an old rope, much

weaker than the trawl-rope, so that, in the event of the net coming in

contact with any obstruction in the water, the ground-rope may break and

allow the rest of the gear to be saved. Were the warp to break instead of

the ground-rope, the whole apparatus, which is of considerable value,

would be left at the bottom. The trawler, as I noted while the net was in

the water, usually sails at the rate of 2 or 2 1/2 knots an hour. The best

depth of water for trawling is from 20 to 30 fathoms, with a bottom of mud

or sand. At times, however, the nets are sunk much deeper than this, but

that is about the depth of water over the great Silver Pits, 90 miles off

the Humber, where a large number of the Hull trawlers go to fish. When

they are caught, the fish (chiefly soles and other flat fish) are then

packed in baskets called pads, and are preserved in ice until brought to

market. To take twelve or fourteen pads a day is considered excellent

fishing. Besides these ground-fish the trawl often encloses haddocks, cod,

and other round fish, when such happen to be feeding on the bottom. It

sometimes happens that the beam falls to the ground, and, the ground-rope

lying on the top of the bag-net, no fish can get in. This accident, which,

however, seldom occurs, is called a back fall. Mr. Vivian of Hull, in a

letter to the editor of a Manchester newspaper, gave two years ago a very

graphic account of the trawl-fishing, and stated that 99 out of every 100

turbot and brills, nine-tenths of all the haddocks, and a large proportion

of all the skate, which are daily sold in the wholesale fish-markets of

this country, are caught by the system of trawling. Trawling is without

doubt the most efficient mode of getting the white fish at the bottom of

the ocean; and were it made penal, London and the large towns would at

times be entirely without fish. As a matter of course, trawling must

exhaust the shoals at particular places. A fleet of upwards of 100 smacks,

each with a beam nearly 40 feet long, trawling night and day, disturbs,

frightens, or captures whatever fish are to be found in that locality,

entrapping, besides, shell-fish, anchors, stores that have been sunken

with ships ages ago; even a wedge of gold has been brought up by this

insatiable instrument. The only remedy is to widen the field of action.

It is best, however, in a case of dispute, as in this

trawl question, to allow those interested to speak for themselves. I have

gone over an immense mass of the evidence taken by a recent commission

appointed by Parliament to make inquiry on the subject, and will set some

parts of it before my readers, so that, if a little trouble be taken in

weighing the pros and cons of the matter, they may be able

to form their own judgment on this vexed question. A Cullercoats

fisherman is very strong against the beam-trawl. He is certain that thirty

years ago we could get double the quantity of fish, during the fishing

season, that we obtain now, and that the supply has fallen away little by

little; and he says that even ten years ago it was almost as good as it

was thirty years ago. Some years hence England will cry out for want of

fish if trawling be allowed to go on. The price of fish has doubled, he

says, of late years. "When I was a young man, there were nine in family of

us, and my wife could purchase haddock for twopence which would serve for

our dinners. Now she could not obtain the same quantity for less than

nine-pence or tenpence. Of recent years the number of fishermen and

fishing-boats has greatly increased. I do not think the fishermen of the

present day are better off than those when I was a young man." The

fishermen at Cullercoats, when they trawl, use the small trawl, and fish

in shallow water. Under these circumstances they do no injury. The

trawlers, with the large trawl, says a Mr. Nicholson who was examined, not

only sweep away the lines of the fishermen, but also destroy the fish. At

Cullercoats a man engaged in the line-fishing gets all the fish on his own

lines, and his wife goes to town and disposes of them. The beam-trawling

commenced about six years ago. The number of boats and the fishing

population still go on steadily increasing. Beam-trawling does two kinds

of harm : in the first place, it sweeps away the fishermen's lines ; and

next, it destroys the spawn. " There may be a remedy for a fisherman

losing his lines, but I never heard of it. I am aware that they could

recover damages, but the difficulty is to get hold of the offending

parties. The only remedy I can suggest is to do away with the

trawl-fishing altogether." This witness stated that ten years ago he used

to take sixty or seventy codfish per day, and that now he cannot get one.

The trawlers, being able to fish in all weathers, beat the local fishermen

out of the field.

Templeman, a South Shields fisherman, says that when

engaged in trawling he has drawn up three and a half tons of fishspawn !

He also says in his evidence that in trawling one-half of the fish are

dead, and so hashed as to be unfit for market. Has seen a ton and a half

of herring-spawn offered for sale as manure. The take of fish upon the

Dogger Bank has decreased very much. The fishermen cannot catch one

quarter part there now that they used to do. The number of trawl-boats on

the Dogger Bank has increased about 10 per cent within the last year, and

yet they are getting about a quarter less fish. Some of them can scarcely

make a living now at all. They have impoverished all other places, and now

they have come here, and in a short time there will not be a fish left. It

is the same with the other fish-banks, and that accounts for the trawlers

now coming to this neighbourhood. They have destroyed the Hartlepool and

Sunderland ground, and now they have come to a small patch off here, and

they will sweep it clean too. A trawlboat will sometimes catch five tons a

day; but on the average a ton and a half; but as a great deal of that has

to be thrown overboard, they only bring about ten cwt. to market. The boats

belonging to Cullercoats, carrying the same number of hands as the

trawlers, only catch upon the average about five stones. The fish caught

in the trawl are not fit for the market, as the insides are broke, and the

galls burst and running through them. " If I had my way, I would pass an

Act of parliament to do away with trawling, and oblige every man to fish

with hooks and lines. I think that would increase the quantity of fish for

the country, because the young fish would not fake the hooks. I am not

aware that if the small boats get five stones a day it would at all

diminish the supply of fish for the market ; but if the trawling is

allowed to continue, that very soon will."

Thomas Bolam, on being examined, said: "I have

followed the herring-fishing for twenty-one years, and the white-fishing

six years. In the course of those six years I have found that the supply

of white fish has gradually diminished both in the number and size of the

fish. In twenty years' experience in the herring-fishing I find a fearful

diminution in the total quantity caught. The shoals of herring are now

only about one-third the size they were when I first commenced the

fishing. At that time we used to get 14,000 or 15,000; now the length of

4000 or 5000 is thought a good take. I attribute the falling-off to the

existence of the trawling system."

Many other fishermen gave similar evidence. A fisherman

named Bulmer, residing at Hartlepool, said that the white fish' were not

only scarcer, but that they were deteriorating in size as well. The

falling off in quantity has decidedly been accompanied by a smaller size,

more particularly in haddocks. Haddocks, twenty years ago, were caught

from five pounds to six pounds in weight ; now they hardly average three

pounds. There is scarcely a single cod to be caught now, and formerly our

boats got them scores together, and had to trail them out in rows, and

could only sell them for about 10s. a score; now they realise at Christmas

5s. and 6s. each. "Of turbot-fishing I am sorry to speak. It pains me to

think of the injuries we have sustained in this particular fishing by

trawlers. At present we dare not cast our nets, as they are sure to be

lost. I lost two `fleets' of turbot-nets worth £25. About twenty-six years

ago I have caught two hundred turbot in one day: now there are none to be

got." Another resident gave similar evidence, and thought that if trawling

was persisted in, their noble bay would soon be fallow ground. John Purvis

of Whitburn also says that haddocks have decreased in size as well as in

quantity-thinks they are at least a third smaller now as compared with

former years. Considers that the trawling system has caused the diminution

of fish which has taken place during the last four years. David Archibald

of Croster had bought trawled fish not for food, as they were only fit to

be used as bait.

Having given a fair sample of the evidence against the

trawling system, it will be but just that we now hear the other side of

the case. It is unfortunate, of course, that we cannot obtain really

impartial evidence on this vexed question, as the party complaining is the

party said to have had their fishery prospects ruined by the use of the

beam-trawl, whilst the trawlers, of course, won't hear a bad word said of

the engine by which they gain their living. A Torbay fisherman, accustomed

to trawling for the last twenty-six years, flatly contradicts much that

has been said against the trawl-net. He asserts that lie never took or saw

any spawn taken, and that only about half a hundredweight in each two tons

of the fish taken is unfit for the market. He does not think the fish are

decreasing either in quantity or size.

A Hull trawler spoke to the following effect:- "I never

saw any spawn in the net. It is impossible for spawn to be caught in the

net. There is often unmarketable fish, but it is only when there is a

strong breeze and a difficulty in getting the gear on board. We generally

get seven or eight hampers in a haul, and one basket would perhaps be

unfit for the market. The hooked fish is a more saleable fish, as it has

got the scales and slime on it, and the trawl fish has not got the slime

on it, and the scales are sometimes rubbed off." Some haddocks were here

produced which the witness said were a fair specimen. The scales were on

them, and on one being opened the inside was found to be in an unbroken

state.

The following is a summary of the

evidence given by William Dawson, a very intelligent fisherman of

Newbiggin, who spoke from fifty years' experience:- "He had fished cod,

ling, turbot, and several kinds of shell-fish, but not oysters. He was

still engaged as a fisherman. He fished with a line for soles. The number

of fishermen and boats had increased. In 1808 there were eight boats, and

there are now about thirty boats. Fifty years ago the boats were about

one-third the size. The boats carried just about the same lines as now.

The boats now carry about three times as much net as they did. The number

of white fish is falling off a great deal. In 1812 every boat brought in

more white fish than they could carry. We do not go much more frequently

to sea now. In the size of the fish now there is not much difference-a

little smaller. The haddock and herring fisheries had decreased. He had

not noticed much difference in the size, only in the quantity. There was a

greater number of boats engaged now in the herring-fishing-the number of

herring having decreased within the last ten or twelve years. Little

mackerel was caught there. Large quantities of mackerel were off this

coast at times, but they had no nets to take them. Although a good many

sprats were seen, they did not try to catch them. The cause of the falling

off in the quantity of fish he considered was their being destroyed

farther south. No trawling vessels came here till last summer. They went

about twelve miles from land, and trawled in the fishing-ground. The lines

of the fishing-boats were parallel, and about a quarter of a mile apart.

When there was a south-east storm they got plenty of fish, but it was not

so now. With a north-east storm they had plenty of fish. In his

recollection, fifty years back, there was plenty of fish with a south-east

storm. There had been no interference with their nets, and no one had

regulated the times of fishing. There might be some advantage if the

Government made a law to prevent either the English or French fishing from

Saturday morning to Monday night. That would give time for the fish to

draw together. That alluded to herring. They should not allow the

trawl-boats to fish on the coasts. The French boats often came within

three miles of the land. Herring are caught within three miles of the

shore. The French boats shifted with the herring along the coast, and have

caught a great quantity. There should be a rule that herring-nets should

not be shot before sunset. When the Queen's cutters came the French boats

made off to more than three miles from the land. Lobsters had diminished,

but not the crabs. He believed they had caught too many lobsters. The

boat's crew is not so well off now as thirty years ago. Lodgings were

better. They do not earn so much money now. In the course of a year (about

1825) he made £126, and a few years back he made only £78. The average for

the last five years at the white fishing was about £50. Other £50 might be

made at the herring-fishing. The buoys of the lines were large enough for

the trawlers to see them, and they could see where the nets were. They

destroyed both the fish and the lines. A line boat with fittings costs

about £40, and a herring-boat with nets not less than £100. The men

bought the boats with money saved. Little fish was destroyed on their

lines, except what was eaten by the dog-fish. There were herring there in

January and February, but were not caught. Their boats fished between

Tynemouth and Dunstanborough castles. He could remember when there were no

French boats on the coast ; they first came about 1824. The French boats

fish on the Sundays. Their boats did not. A young man ought to earn £100 a

year. It would cost a full third to keep his boat and tackling up. The

boats lasted about fourteen years."

I need not go on repeating similar

evidence, but the witnesses were nearly all agreed that the beam-trawl did

not do the injury to the fisheries that was charged against it, especially

as regards injury to spawn. I may perhaps, by way of conclusion to this

contradictory evidence, be allowed to quote from the Times a

portion of a letter on trawling, written by a "Billingsgate Salesman:" -

"Seven years' experience in Billingsgate, and my lifetime previous spent

among the fishermen in a seaport-town, may enable me to offer a few

remarks, which through your able abilities may be sifted, and perhaps

leave a portion of matter which you may consider of some value and turn to

some account. My personal interest is not only in trawl-fishing, but

hook-and-line, seined-net, drift-net, and other kinds; for, being a

commission agent, it is all fish that comes to my net. I cannot speak of

the qualities of trawl-net fishing, either for or against, not having been

connected with that branch of the trade, but after a remark or two on the

information received by Mr. Fenwick, and which is conveyed in your columns

from certain gentlemen professing to have a knowledge of the trade, I will

give you my information as briefly as possible. The fact is this-it never

will be possible to catch what we consider trawl-fish in sufficient

quantities to meet the demand but by the trawl, the principal kinds being

turbot, brill, soles, and plaice. A small quantity may be taken by other

means, but more by accident then otherwise. As for trawl-fish being

mutilated and putrid before landing, how does it happen that so many

spotless and pure fish, out of the above kinds, are not only sold in

London but all over the country, and exhibited on the tables both of rich

and poor ? Yourself and every nobleman can speak on this point; and when

informed that they are all caught by the trawl (a fact undeniable), you

will consider it wrong on the part of any one to mislead the public on a

matter of so much importance. Advise him to fathom the secrets of the

ocean, and discover a better mode to obtain them."

A great deal of obloquy has been

thrown on the trawl, because it hashes the fish ; but the

destruction of young fish - that is, fish unfit for human food because of

their being young - is not peculiar to the trawl. When the lines are

thrown out for cod the fishermen cannot command that only full-grown fish

are to seize upon the bait : the tender codling, the unfledged haddock,

the greedy mackerel, will bite-the consequence being that thousands

of sea-fish are annually killed that are unfit for food, and that have

never had an opportunity of adding to their kind. But this mischance is

incidental to all our fisheries, no matter what the engine of capture may

be, whether net or line. Look how we slaughter our grilses, without giving

them the opportunity of breeding ! The herring-fishing is a notable

example of this mode of doing business : the very time that these animals

come together to perpetuate their species is the time chosen by man to

kill them. Of course if they are to be used as food, they must be killed

at some time, and the proper time to capture them forms one of those

fishing mysteries which we have not as yet been able to solve. We protect

the salmon with many laws at the most interesting time of its life, and

why we should not be able to devise a close-time for the cod, turbot,

haddock, and sole of particular coasts-for each portion of the coast has

its particular season-is what I cannot understand, and can only account

for the anomaly on the ground of salmon being private property.

The labour of the Scottish fishermen

is greatly augmented by the want of good harbours for their boats. Time

and opportunity serving, the men of the fisher class are really

industrious, and this want of proper harbourage is a hardship to them. It

is curious to notice the little quarry-holes that on some parts of the

Moray Firth serve as a refuge for the boats. There is the harbour of

Whitehills, for instance : it could not be of any possible use in the

event of a stiff gale arising, for in my opinion the boats would never get

into it, but would be dashed to pieces on the neighbouring rocks. I have

witnessed one or two storms on the north-east coast of Scotland, and shall

never forget the scenes of misery these tumults of the great deep

occasioned.

Large quantities of white fish are,

of course, still caught on the Scottish coasts. Almost in every little bay

and firth there are some boats constantly engaged in the haddock and cod

fishing, and if we ask the destination of those fish which are caught, the

answer is almost sure to be " the English markets." The constant and

unvarying demand for fresh fish from the larger towns of England so

entices the fishermen, that local demands are entirely slighted. On the

coasts of Ayrshire and Galloway, all the fish I inquired about, that is,

all that were brought ashore during my visits to several fishing towns,

were destined for either Manchester or London. Wherever there is a railway

reaching to the sea-side, it may be accepted as a settled fact that a

portion of its revenue will be derived from the carriage of fish to great

seats of population.

The following tabular view of the dates when our

principal fishes are in season does not refer to any particular locality,

but -bas been compiled to show that fish are to be obtained nearly all the

year round from some part of the coast :

FISH TABLE.

S denotes that the fish is in season; F in finest

season; and

O out of season.

|

Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

|

Brill |

S |

S |

S |

S |

S |

S |

S |

S |

S |

S |

S |

S |

|

Carp |

S |

S |

S |

S |

S |

S |

S |

S |

S |

S |

S |

S |

|