Classification of Fish - Their Form and Colour - Mode and Means of Life

- Curiously-shaped Fish - Senses of Smell and Hearing in Fish - Fish

nearly Insensible to Pain - The Fecundity of Fish - Sexual Instinct of

Fish - External Impregnation of the Ova - Ripening of a Salmon Egg -

Birth of a Herring - The Rich versus the Poor Man's Fish - Curious

Stories about the Growth of the Eel - All that is known about the

Mackerel-Whitebait-Mysterious Fish: the Vendace and the Powan -Where are

the Haddocks? - The Food of Fish - Fish as a rule not Migratory - The

Growth of Fish Shoals - When Fish are good for Food - The Balancing

Power of Nature.

FISH form the fourth class of

vertebrate animals, and, as a general rule, live in water; although in

Ceylon and India species are found that live in the earth, or, at any

rate, that exist in mud, not to speak of others said to occupy the trees

of those countries! The classification of fishes given by Cuvier is

usually adopted. He has divided these animals into those with true bones,

and those having a cartilaginous structure; the former, again, being

divided into acanthopterous and malcopterous fish. Other naturalists have

adopted more elaborate classifications; but Cuvier’s being the simplest

has a strong claim to be considered the best, and is the one generally

used.

A fish breathes by means of its

gills, and progresses chiefly by means of its tail. This animal is

admirably adapted for progressing through the water, as may be seen from

its form, and fish are exceedingly beautiful, both as regards shape and

colour. There are comparatively few persons, however, who have an

opportunity of seeing them at the moment of their greatest brilliancy,

which is just when they are brought out of the water. I allude more

particularly to some of our sea fish—as the herring, mackerel, etc. The

power of a fish to take on the colour of its hiding-place may be

mentioned; various kinds, when in the water, as may be observed at the

Brighton and Crystal Palace Aquariums, are not to be distinguished from

the vegetable matter in which they take shelter. It is almost impossible

to paint a fish so as accurately to transmit to canvas its exquisite shape

and glowing colours, because the moment it is taken from its own element

its form alters and its delicate hues fade: and in different localities

fish have, like the chameleon, different hues, so that the artist must

have a quick eye and a responding hand to catch the fleeting tints of the

animal. Nothing, for instance, can reveal more beautiful masses of colour

than the hauling in of a drift of herring-nets. As breadth after breadth

emerges from the water the magnificent ensemble of the fish flashes

ever-changing upon the eye—a wondrous gleaming mixture of blue and gold,

silver and purple, blended into one great burning glow, and lighted to

brilliant life by the soft rays of the newly-risen sun. But, alas for the

painter! unless he can instantaneously fix the burnished mass on his

canvas, the light of its colour will fade, and its harmonious beauty

become dim, long before the boat can reach the harbour. The brightly-coloured

fish of the tropics are gorgeous, as the plumage of tropical birds ; but

as regards flavour and food power, they cannot for a moment be compared

with that beautiful fish—the common herring, or pilchard, of our British

waters.

If the breathing apparatus of a fish

were to become dry the animal would at once suffocate. When in the water a

fish has very little weight to support, as its specific gravity is about

the same as that of the element in which it lives, and the bodies of these

animals are so flexible as to aid them in their movements, while the

various fins assist either in balancing the body or in aiding progress.

The motion of a fish is excessively rapid; it can dash through the water

with lightning-like velocity. Many of our sea fish are curiously shaped,

such as the hammer-headed shark, the globe-fish, the monk-fish, the

angel-fish, etc.; then we have the curious forms of the rays, the

flounders, and of some other "fancy fish ;" but all kinds are admirably

adapted to their mode of life and the place where they live—as, for

instance, in a cave where light has never penetrated fish have been found

without eyes! Fresh-water fish do not vary much in shape, most of them

being very elegant. Fish are cold-blooded, and nearly insensible to pain,

their blood being only two degrees warmer than the element in which they

live. It is worthy of note that fish have small brains compared to the

size of their bodies—considerably smaller in proportion than in the case

of birds or mammalia, but the nerves communicating with the brain are as

large in fish, proportionately, as in birds or mammalia. The senses of

sight and hearing are thought to be well developed in fish, likewise those

of smell and taste, particularly smell, which chiefly guides them in their

search for food. Fish, I think, have a very keen scent; thus it is that

strong-smelling baits are successful in fishing. The French people, for

instance, when fishing for sprats and sardines, bait the ground with

prepared cod-roe, which adds largely to the expense of that branch of

fishing in the Bay of Biscay. As an evidence of fish having a strong sense

of smell, salmon-roe used to be a deadly trout-bait. Some naturalists

assert that fish do not hear well, which is contrary to my own experience;

for after repeated trials of their sense of hearing, I found them as quick

in that faculty as in seeing; and have we not all read of pet fish

summoned to dinner by means of a bell, and of trouts and cod-fish that

have been whistled to their food like dogs ?

Water is an excellent conducter of sound: it conveys

noise of any kind to a great distance, and nearly as quick as air.

Benjamin Franklin often experimented on water as a

conductor, and arrived at the conclusion that its powers in this way are

wonderful. Most kinds of fish are voracious feeders, preying upon each

other without ceremony; and the greatest difficulties of anglers are

experienced after fish have had a good feed, when the practised artist,

with seductive bait, cannot induce them even to nibble. Many fish have a

digestion so rapid as to be comparable only to the action of fire, and on

good feeding-grounds the growth of fish corresponds to their power of

eating. In the sea there exists an admirable field for observing the

cannibal propensities of fish, where shoals of one species have apparently

no other object in life than to chase other kinds with a view to eat them.

To compensate for the waste of life incidental to their

place of birth and their ratio of growth, nature has endowed this class of

animals with enormous reproductive power. Fish yield their eggs by

thousands or millions, according to the danger incurred in the progress of

their growth. There is nothing in the animal world that can in this

respect be compared to them, except perhaps a queen bee, with fifty

thousand young each season; or the white ant, which produces eggs at the

rate of fifty per minute, and goes on laying for a period of unknown

duration; not to speak of that terrible domestic bugbear which no one

likes to name, but which is popularly supposed to become a

great-grandfather in twenty-four hours! The little aphides of the garden

may also be noted for their vast fecundity, as may likewise the common

house-fly. During a year one green aphis may produce one hundred thousand

millions of young; and the house-fly lays twenty millions of eggs in a

season ! But although there may be thirty thousand eggs in a herring, the

reader must bear in mind that if these be not vivified by the milt of the

male fish, they rot in the sea, and never become of food value, except

perhaps to some minor monster of the deep. Millions of the eggs that are

emitted by the cod or the herring never come to life—many of them from

lack of fructifying power, others being devoured by enemies. Then, again,

of those eggs that are ripened, it is ascertained from careful inquiry,

that fully ninety per cent of the young fish perish before they are six

months old. Were only half the eggs to come to life, and but one moiety of

the young fish to live, the sea would so abound with animal life that it

would be impossible for a boat to move in its waters. But we can never

hope to realise such a sight; and when it is considered that a single

shoal of herrings consists of many millions of individual fish, and takes

up a space in the sea far more than that occupied by the city of London,

and yet gives no impediment to navigation, my readers will see the

magnitude of our fish supplies; but, by the destruction of fish life from

natural causes, the breeding stock is kept down to an amount that may not

be far from the point of extermination.

The figures of fish fecundity are quite reliable, and

are not dependent on guessing, because different persons have taken the

trouble, the writer among others, to count the eggs in the roes of some of

our fish, that they might ascertain exactly their amount of breeding

power. It is well known that the female salmon yields eggs at the rate of

about one thousand for each pound weight, and some fresh-water fish are

even more prolific; sea fish, again, far excelling these in reproductive

power. The sturgeon, for instance, is wonderfully fecund, as much as two

hundred pounds weight of roe having been taken from one fish, yielding a

total of 7,000,000 of eggs. I possess the results of several

investigations into fish fecundity, which were conducted with attention to

details, and without any desire to exaggerate: these give the following

results :—Cod-fish, 3,400,000; flounder, 1,250,000; sole, 1,000,000;

mackerel, 500,000; herring, 35,000, and smelt, 36,000.

Any person who wishes to manipulate these figures may

try by way of experiment a few calculations with herring. The produce of a

single herring is, say, thirty-six thousand eggs, but we may—the deduction

being a most reasonable one—allow that half of these never come to life,

which reduces the quantity to eighteen thousand. Allowing that the young

fish are able to repeat the story of their birth in three years, we may

safely calculate that the breeding stock by various accidents will be

reduced to nine thousand individuals; and granting half of these to be

females, or let us say, for the sake of rounding the figures, that four

thousand of them yield roe, we shall find by multiplying that quantity by

thirty-six thousand (the number of eggs in a female herring) that we

obtain one hundred and forty-four millions as the produce in three years

of a single pair of herrings; and although half of these might be taken

for food as soon as they were large enough, there would still be left an

immense breeding stock even after all casualties had been given effect to;

so that the devastations committed on the shoals while capturing for food

uses must be enormous, if, as is asserted, they affect the

reproductiveness of these useful animals. Of course this is but guesswork.

Practical people do not think that, taking all times and seasons into

account, five per cent of the roe of our herrings come to life.

It is known even to tyros in the study of

natural history, as well as anglers and others interested, that the

impregnation of fish-eggs is a purely external act; but at one time this

was not believed, and a portion of the experiments at the Stormontfield

salmon-breeding ponds was dedicated to a solution of this question, with

what result may be guessed. The old theory, that it is contrary both to

fact and reason that fish can differ from land animals in the matter of

the fructification of their eggs, was signally defeated, and the question

conclusively settled at the ponds in a very simple way—namely, by placing

in the breeding-boxes a quantity of salmon eggs which not having been

brought into contact with milt, rotted away. Curious ideas used to prevail

on this branch of natural history. Herodotus observes of the fish of the

Nile, that at the spawning season they move in vast multitudes towards the

sea; the males lead the way, and emit the engendering principle in their

passage; this the females absorb as they follow, and in consequence

conceive, and when their ova are deposited they arc then matured into fry!

Linnaeus backed up this idea, and asserted that there could be no

impregnation of the eggs of any animal out of the body. It is this

wonderfully exceptional principle in fish life that gave rise to

pisciculture—i.e. the artificial impregnation of the eggs of fish forcibly

exuded and brought into contact with the milt, independent altogether of

the will or instinct of the animal.

The principle which brings male and female together at

the spawning period is unknown. It is supposed by some naturalists that

fish do not gather in shoals till they perform the grandest action of

their nature, and that till such period each animal lives a separate life.

If we set down the sense of smell as the power which attracts the fish

sexes, we shall be nearly correct: cold-blooded animals cannot have any

more powerful instinct. A very clever Spanish writer on pisciculture hints

that the fish have no amatory feeling for each other at that period, thus

forming a curious exception to most other animals, and that it is the

smell of the roe in the female which attracts the male.

This idea—viz, as to the shoaling of fish at the period

of spawning only—has been thrown out in regard to the herring by parties

who do not admit even a partial migration from deep to shallow water,

which, however, is an idea stoutly held by some writers on the herring. It

is rather interesting, however, in connection with this phase of fish

life, to note that particular shoals of herrings deposit their spawn at

particular places, that the eggs come simultaneously to life, and that it

is certain that the young fish remain together for a considerable period—a

few months at least—after being hatched. This is well known from large

bodies of young herrings being caught during the sprat season: these could

not, of course, have assembled to spawn; too young, and without milt or

roe. This, if these fish separate, gives rise to the question—At what

period do the herrings begin their individual wanderings? Sprats, of

course, may have come together, at the period when they are so largely

captured, for the purpose of perpetuating their kind; but, if so, they

must live long together before they acquire milt or roe. And how is it

that we so often find young herrings in sprat shoals? Then, again, how

comes it that fishermen do not frequently fall in with the separate

herrings during the white-fishing seasons? How is it that fisher-men find

particular kinds of fish always on particular ground? How is it that eels

migrate in immense bodies? My opinion is, that particular kinds of fish do

hold always together, or, at all events, gather at particular seasons into

greater or lesser bodies. Life among the inhabitants of the sea is,

doubtless, quite as diversified as life on land, where we observe that

many kinds of animals colonise—ants, bees, etc. Are, therefore, the old

stories about each kind of fish having a king so absolutely incredible

after all? That there are schools of fish is certain; how the great bodies

may be divided or governed, none can tell.

It is noteworthy that fish-eggs afford us an admirable

opportunity of studying a peculiarly interesting stage of animal life—

namely, the embryo stage—which, naturally enough, is obscure in all

animals. Having observed the eggs of salmon in all stages of progress,

from the period of their first contact with the milt till the bursting of

the egg and the coming forth of the tiny fish, I venture briefly to

describe what I have seen, because salmon eggs are of a convenient size

for continued examination. The roe of this fine fish is, I daresay, pretty

familiar to most of my readers. The microscope reveals the eggs of salmon

as being more oval than round, although they appear quite round to the

naked eye. A yolk seems to float in the dim mass, and the skin or shell

appears full of minute holes, while there is an appearance of a kind of

funnel opening from the outside and apparently closed at the inner end.

The milt is found to swarm with a species of very small creatures with big

heads and long tails, apparently of very low organisation. On the contact

of this fluid with the egg, into which it enters by the canal, an

immediate change takes place—the ovum becomes illuminated by some curious

power, and the egg appears a great deal brighter and clearer than before.

It is surely wonderful that, by the mere touching of the egg with this

wonder-working sperm, so great a change should take place—a change

indicating that the grand process of reproduction characteristic of all

living nature has begun, and will go on with increasing strength to

maturity.

Salmon-spawn is so accessible, comparatively speaking,

as to render it easy to trace the development from the egg of the complete

animal. As may be supposed, however, the transmutation of a salmon egg

into a fish is a tedious process, taking above a hundred days. The eggs of

the female, under the natural system of spawning, are laid in the secluded

and shallow tributary of some choice stream, in a trough of gravel

ploughed up by the fish with great labour, and are there left to be wooed

into life by the eternal murmuring of the water. From November tifi March,

through the storms and floods of winter, the ova lie hid among the gravel,

slowly but surely quickening into life; and few persons would guess, from

a mere casual glance at the tributary of a great salmon stream, that it

held among its bubbling waters such countless treasures of future fish.

Practised persons will find a burrow of salmon eggs with great precision;

and a little bit of water may contain perhaps a million eggs waiting to be

summoned into life. During the first three weeks from the milting of the

egg, scarcely any change is discernible in its condition; except that

about the end of that period it contains a brilliant spot, which gradually

increases in

brilliancy till certain threads of blood faintly

prefigure the young fish. After another day or two the bright spot assumes

a ring-like form, having a clear space in the centre, and the

blood-threads then become more and more apparent. These blood-like

tracings are ultimately seen to take an animal shape; but it would be

difficult at first to say what the animal may turn out to be—whether a

tadpole or a salmon. After this stage of development is reached, two

bright black specks are seen— these are the eyes of the fish. We can now,

from day to day, note the animal gradually assuming a more perfect shape;

we can see it change palpably almost from hour to hour. After the egg has

been laved by the water for a hundred days, we can observe that the young

fish is then thoroughly alive, and, to use a common expression, kicking.

We can see it moving, and can study its anatomy, which, although as yet

very rudimentary, contains all the elements of the perfect fish. Heat

expedites the birth of the animal. The eggs of a minnow have been sensibly

advanced towards maturity by being held on the palm of the hand. Salmon

eggs deposited early in the season, when the temperature is high, come

sooner to life than those spawned in mid-winter: indeed a difference of as

much as fifty days has been noticed between those deposited in September

and those spawned in December, the one requiring ninety, the other one

hundred and forty days to ripen into life. Salmon have been brought to

life in sixty days at Huningue; but the quickest hatching ever

accomplished at the Stormontfield breeding-ponds was when the fish came to

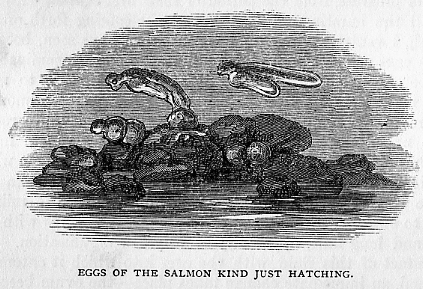

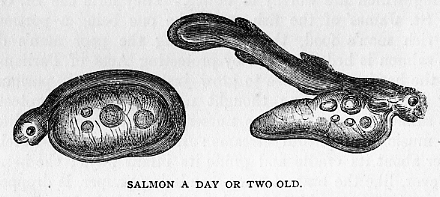

life in one hundred and twenty days. The preceding drawing shows the eggs

at about their natural size, as also the growth of the fish in its early

stages.

At the salmon-ponds of Stormontfield the eggs laid down

the first season were hatched in one hundred and twenty-eight days. The

usual time for the hatching of salmon eggs in our northern rivers is one

hundred and thirty days, or between four

and five months, according to the openness or severity

of the season. When at last the infant animal bursts from its fragile

prison, it is a clumsy, unbalanced, tiny thing, having attached to it the

remains of the parental egg, which hamper its movements; but, after all,

the remains of its little prison are exceedingly useful, as for about

thirty days the young salmon cannot obtain other nourishment than what is

afforded by this umbilical bag.

We have never yet been able to obtain a sight of the

ripening eggs of any of our sea fish at a time when they would prove

useful to us. No one, so far as I know, has seen the young herring burst

from its shell under such advantageous circumstances as we can view the

salmon ova; but I have seen bottled-up spawn of that fish just after it

had ripened into life, the infant animal being remarkably like a fragment

of cotton thread that had fallen into the water: it moved about with great

agility, but required the aid of a microscope to make out that it was a

thing endowed with life. Who could suppose, while examining those wavy

floating threads, that in a few months afterwards they would be grown into

beautiful fish, with a mechanism of bones to bind their flesh together,

scales to protect their body, and fins to guide them in the water But

young herring cannot be long bottled up for observation, or be kept in an

artificial atmosphere; for in that condition they die almost before there

is time to see them live; and when in the sea there are no means of

tracing them, because they are speedily lost in an immensity of

water. Perhaps now that we have large aquariums at Brighton and the

Crystal Palace, we shall be able to trace the progress of the fish with

more exactitude.

There are points of contrast between the salmon and the

herring which are worthy of notice. They form the St. Giles’ and St.

James’ of the fish world, the one being a portion of the rich man’s food,

the other filling the poor man’s dish. The salmon is hedged round by

protecting Acts of Parliament, but the herring gets leave to grow just as

it swims, parliamentary statutes not being thought necessary for its

protection. The salmon is born in a fine nursery, and wakened into life by

the music of beautiful streams : nurses and night-watchers, hover adout

its cradle and guide its infant ways ; the herring, however, like the brat

of some wandering pauper, is dropped in the great ocean workhouse, and

cradled amid the hoarse roar of ravening waters, whether it lives or dies

being a matter of no moment, and no person’s business. Herring mortality

in its infantile stages is appalling, and even in its old age, at a time

when the rich man’s fish is protected from the greed of its enemies, the

herring is doomed to suffer the most. And then, to finish up with the same

appropriateness as they have lived, the venison of the waters is daintily

laid out on a slab of marble, while the vulgar but beautiful herring is

handled by a dirty costermonger, who drags it about in a filthy cart drawn

by a wretched donkey. At the hour of reproduction the salmon is guarded

with jealous care from the hand of man, but at the same season the herring

is offered up a wholesale sacrifice to the destroyer. It is only at its

period of spawning that the herring is fished. How comes it to pass that

what is a high crime and misdemeanour in the one instance is a

government-rewarded merit in the other ? To kill a gravid salmon is as

nearly as possible felony ; but to kill a herring as it rests on the

spawning-bed is an act at once meritorious and profitable!

Having given my readers a general idea of the fecundity

of fish, and the method of fructifying the eggs, and of the development of

these into fish—for, of course, the process will be nearly the same with

all kinds of fish eggs, the only difference perhaps being that the eggs of

some varieties will take a longer time to hatch than those of others—I

will now consider the question of fish growth.

All fish are not oviparous. There is a well-known

blenny which is viviparous, the young of which at the time of their birth

are so perfect as to be able to swim about with great ease; and this fish

is also very productive. Our skate fishes are all viviparous. "The young

are enclosed in a horny capsule of an oblong square shape, with a filament

at each corner. It is nourished by means of an umbilical bag till the due

period of exclusion arrives, when it enters upon an independent

existence." I could name a few other fish which are viviparous. In the

fish-room of the British Museum may be seen one of these. It is known as

Ditrenia argentea, and is plentifully found in South America. But

information on this portion of the natural history of fish is still very

obscure. Many facts of fish biography have yet to be ascertained, which,

if we knew, would probably conduce to stricter economy of fish life and

better regulation of the fisheries. Beyond a knowledge of generalities,

the kingdom of the sea is a sealed book. No person can tell, for example,

how long a time elapses from the birth of any particular fish till it is

brought to table. Sea fish grow up unheeded—quite, in a sense, out of the

bounds of observation. Naturalists can only guess at what rate a cod-fish

grows. The life of a herring, in its most important phase, is still a

mystery; and at what age mackerel or other fish becomes reproductive, who

can say? The salmon is the one fish that has hitherto been compelled to

render up to those inquiring the secret of its birth and the ratio of its

growth. We have imprisoned this valuable fish in artificial ponds, and by

robbing it of its eggs have noted when the young ones were born and how

they grew, why then not devise a means of observing sea fish at the

expense of the nation? What naturalists chiefly and greatly need in

respect of sea fish is, precise information as to their rate of growth. We

have a personal knowledge of the fact of sea fish selecting our shores as

a spawning-ground, but we do not precisely know in some instances the

exact time of spawning, how long the spawn takes to quicken into life, or

at what rate the fish increase in growth. The eel may be taken as an

example of our ignorance of fish life. Do professed naturalists know

anything about it beyond its migratory habits ?—habits which, from sheer

ignorance, have at one period or another been assumed as pertaining to all

kinds of fish. The tendency to the romantic, specially exhibited in the

amount of travelling power bestowed by the elder naturalists on this class

of animals, would seem to be very difficult to put down. An old story

about the eel was gravely revived a few years ago, having the larger

portion of a little book devoted to its elucidation—a story seriously

informing us that the silver eel is the product of a black beetle! But no

one need wonder at a new story about the eel, far less at the revival of

this old one; for the eel is a fish that has at all times experienced the

greatest difficulty in obtaining recognition as being anything at all in

the animal world, or as having respectable parentage of even the humblest

kind. In fact, the study of the natural history of the eel has been

hampered by old-world romances and quaint fancies about its birth, or, in

its case, may I not say invention? "The eel is born of the mud," said one

old author. "It grows out of hairs," said another. "It is the creation of

the dews of evening," exclaimed a third. "Nonsense," emphatically uttered

a fourth controversialist, "it is produced by means of electricity." "You

are all wrong," asserted a fifth, "the eel is generated from turf;" and a

sixth theorist, determined to outdo all others, and come nearer the mark

than any of his predecessors, assured the public that young eels are grown

from particles scraped off old ones ! The beetle theorist tells us that

the silver eel is a neuter, having neither milt nor roe, and is therefore

quite incapable of perpetuating its kind; that, in short, it is a romance

of nature, being one of the productions of some wondrous

lepidopterous animals seen by Mr. Cairncross (the author of the work

alluded to) about the place where he lived in Forfarshire, its other

production being of its own kind, a black beetle! The story of the rapid

growth and transformatian of the salmon is—as will by and by be seen—

wonderful enough in its way, but it is certainly far surpassed by the

extraordinary silver eel, which is at one and the same time a fish and an

insect.

There can be no doubt that the eel is a curious animal

even without the extra attributes bestowed upon it by this very original

naturalist, for that fish is in many respects the opposite of the salmon:

it is spawned in the sea, and almost immediately after coming to life

proceeds to live in brackish or entirely fresh water. It is another of the

curious features of fish life that about the period when eels are on their

way to the sea, where they find a suitable spawning-ground, salmon are on

their way from the sea to the river-heads to fulfil the grand instinct of

their nature—namely, reproduction. The periodical migrations of the eel,

on which has been founded the great fishing industry of Comacchio, on the

Adriatic, can be observed in all parts of the globe: they take place,

according to climate, at different periods from February to May; the fish

frequenting such canals or rivers as have communication with the sea. The

myriads of young eels which ascend are almost beyond belief; they are in

numbers sufficient for the population of all the waters of the globe—that

is, if there were reservoirs in which they might be preserved for food as

required. The eel, indeed, is quite as prolific as the generality of sea

fish. Eels have been noted to pass up a river from the sea at the

extraordinary rate of eighteen hundred per minute! This montee used

to be called eel-fair.

It would be interesting, and profitable as well, to

learn as much of any one of our sea-fish as we know of the salmon, and as

considerable progress is now being made in observing the natural history

of fish, we expect in time to know much more than we do at present;

everything in the fish world is not taken for granted as formerly,

although we are still inclined rather to revive old traditions than to

study or search out new facts. Naturalists are so ignorant of how the work

of growth is carried on in the fish world—in fact, it is so difficult to

investigate points of natural history in the depths of the sea— that we

cannot wonder at less being known about marine animals than about any

other class of living things. The experiments carried on at the Brighton

Aquarium may ultimately help us to more precise information. In that

institution there is scope and verge enough for real practical work to be

carried on. It is the want of precise information about the growth of fish

that tells so heavily against our fisheries, for all is fish that comes to

the fisherman’s net, no matter what size the animals may be, or whether

they have been allowed to perpetuate their kind. No person, either

naturalist or fisherman, knows how long a period elapses from the date of

its birth till a turbot or cod-fish becomes reproductive. It is now well

known, in consequence of repeated experiments, that salmon grow with

immense rapidity, a consequence in some degree of quick digestive power.

The cod-fish, again, reasoning from the analogy of its greatly slower

power of digesting its food and from other corroborative circumstances,

must be correspondingly slow in growth; but people must not, in

consequence of this slower power of digestion, believe all they hear about

the miscellaneous articles often said to be found in stomachs of cod-fish,

as a large number of the curiosities found in the intestinal regions of

his codship are placed there by fishermen, as a joke, or to increase the

weight, and so enhance the price of the animal.

As regards the natural history of one of our best-known food fishes, I

have taken the pains to compile a brief precis of its life from the best

account of it that is known. I allude to the mackerel; and from a perusal

of the following facts it will be seen that our knowledge of the growth of

this fish is very defective. 1. Mackerel, geographically speaking, are

distributed over a wide expanse of water, embracing the whole of the

European coasts, as well as the coasts of North America, and this fish may

be caught as far southward as the Canary Islands. 2. The mackerel is a

wandering unsteady fish, supposed to be migratory, but individuals are

always found in the British seas. 3. This fish appears off the British

coasts in quantity early in the year; that is, in January and February. 4.

The male kind are supposed to be more numerous than the female. 5. The

early appearance of this fish is not dependent on the weather. 6. The

mackerel, like the herring, was at one time supposed to be a native of

foreign seas. 7. This fish is laden with spawn in May, and it has been

known to deposit its eggs upon our shores in the following month. Now, we

have no account here of how long it is ere the spawn of the mackerel

quickens into life, or at what age that fish becomes reproductive,

although in these two points is unquestionably obtained the key-note to

the natural history of all fishes, whether they be salmon or sprats.

In fact we have no precise information whatever as to power of growth. We

have at best only a few guesses and general deductions, and we would like

to know as regards all fish—1st, When they spawn; 2d, How long it is ere

the spawn quickens into life; and 3d, At what period fish are able to

repeat the story of their birth. These points once known—and they are most

essential to the proper understanding of the economy of our fisheries—the

chief remaining questions connected with fishing industry would be of

comparatively easy solution, and admit of our regulating the power of

capture to the natural conditions of supply.

As another example of long continued ignorance of fish life, I may

instance that diminutive member of the herring family— the whitebait. This

fish, which is so much better known gastronomically than it is

scientifically, was thought at one time to be found only in the Thames,

but it is much more generally diffused than is supposed. It is found for

certain, and in great plenty, in three rivers—viz, the Thames, the Forth,

and the Hamble. I have also seen it taken out of the Humber, not far from

Hull, and have heard of its being caught near the mouth of the Deveron, on

the Moray Firth; and likewise of its being found in plentiful quantities

off the Isle of Wight. Mr. Stewart, the natural history draughtsman, tells

me also that he has seen it taken in bushels on many parts of the Clyde,

and that at certain seasons, while engaged in taking coal-fish, he has

found them so stuffed with whitebait that by holding the large fish by the

tail the little silvery whitebait have fallen out in handfuls. The

whitebait has become celebrated from the mode in which it is cooked, and

the excuse it affords to Londoners for an afternoon’s excursion, as also

from its forming a famous dish at the annual fish-dinner of her Majesty’s

ministers; but truth compels me to state that there is nothing in

whitebait beyond its susceptibility of taking on flavour from the skilled

cook.

The whitebait, however, if I cannot honestly praise it as a table fish, is

particularly interesting as an object of natural history, there having

been from time to time, as in the case of most other fish, some very

learned disputes as to where it comes from, how it grows, and whether or

not it be a distinct member of the herring family or the young of some

other fish. The whitebait—which, although found in rivers, is strictly

speaking a sea fish—is a tiny animal, varying in length, when taken for

cooking purposes, from two to four inches, and has never been seen of

greater length than five inches. In appearance it is pale and silvery,

with a greenish back, and should be cooked immediately after being caught;

indeed if, like Lord Lovat’s salmon, whitebait could leap from the water

into the frying-pan, it would be a decided advantage to those dining upon

it, for if

kept even for a few hours it becomes greatly deteriorated, and, in

consequence, requires careful cooking to bring the flavour up to the

proper pitch of gastronomic excellence. Perhaps, as all fish are

chameleon-like in reflecting not only the colour of their abode, but what

they feed on as well, the supposed fine flavour of whitebait, so far as

not conferred upon that fish by the cook, may arise from matters held in

solution in the Thames water, and so the result from the corrupt source of

supply may be a quicker than ordinary decay. The waters of the Forth at

the whitebait ground, a little way above Inchgarvie, of which I have given

a slight sketch, where the sprat-fishing is usually carried on, are clean

and clear, and the fish taken there are in consequence slightly different

in colour, and greatly so in taste, from those obtained in the Thames; in

fact. all kinds of fish, including salmon, live and thrive in the Firth of

Forth. It is long since the refined salmon forsook the Thames but then

salmon are very delicate in their eating, and at once take on the

surrounding flavour, whatever that may be.

Returning, however, to our whitebait, we have over and over again been

assured by various authorities that that fish is the young of the shad;

and a whole regiment of the young fish was shown by Mr. Larkin, a

Cheapside fishmonger, in order to prove the case. All sizes were

marshalled in order, from the tiniest specimen to the comparatively

monster parent of the progeny—the great shad itself. The verdict must,

however, in the meantime be the Scotch one of “not proven.” It is not very

well known who first promulgated the theory of whitebait being the young

of the shad; but Donovan, the author of a History of British Fishes, is at

least responsible for spreading the error. What must, however, surprise

all who take the trouble to study the controversy is this fact, that if

whitebait be young shad, their parents are very seldom seen. There is no

shad-fishery in the Thames, or near the Thames, at present; yet millions

of these so-called young shad are annually devoured by visitors to

Greenwich, Blackwall, and Richmond, not to speak of the number eaten in

the great metropolis. If the progeny, then, are plentiful, how come the

parents to be scarce? is the idea immediately presenting itself to the

mind when requested to believe whitebait to be young shad. Fishes of all

kinds, and especially the herring kind, are very prolific; but even if the

female shad yields its ova in thousands, the dangers the young ones

encounter considerably diminish the number that come to life. Thousands of

pairs of shads would therefore be required to produce the quantities of

so-called whitebait which are annually brought to table during the summer

season. Shad were at one time very abundant in the Thames; and this fact

would no doubt be a good argument in the mouths of those who were of

opinion that whitebait grew in time into that fish. If, however, we reject

the shad as the parent of the whitebait, and conclude that fish to be a

distinct species, we shall undoubtedly want to know a great deal more

about it than that bare fact. First of all, we must know where the parent

fish can be found; secondly, if they be good for food; and thirdly, at

what season and in what markets they are sold: it seems so strange that we

should be addicted to eating the fry of a fish we never see! Besides, may

we not reasonably enough conclude that if the fry be so very fine, the

full-grown fish will be even more palatable? It is curious that while

there are thousands of whitebait in the Firth of Forth, and equally

curious that they are caught chiefly on the sprat-ground there, no

Edinburgh fishmonger, nor any of the Scottish fishermen, ever saw

specimens of these fish with milt or roe in them. Nor did any of these

persons ever see a whitebait bigger than the usual size, that is, ranging

in length from one to about three inches. After they attain that size they

become either sprats or herrings.

If what some naturalists have published in regard to its habits be true,

the shad must be a very interesting fish. It has been hinted that it

ascends from the sea to deposit its spawn in the rivers, being something

like the salmon in that respect. In this phase of its life it is the

opposite of the eel, which lives in fresh but spawns in salt water. What

salmon do, shad can doubtless also accomplish, although it will go a long

way to disprove what has been said by naturalists, if the shad should be

proved not to be the parent of the whitebait, or rather, if it can be

proved that whitebait are the young of some other fish. In the days when

the herring was thought to be an animal migratory habits, rushing

continually from our own firths and bays to the icy polar seas, some of

the giants of the tribe were poetically described as swimming in the van

of the mighty heer, acting as the guides and leaders of the smaller fish.

These giants were Thwaite shads; but as it is now well known that the

herring is local in its habits, and not migratory in the sense of taking

long journeys, the shad must therefore be deposed from that leadership;

nor can it be, even allowed the merit of being a tolerable table-fish, it

is a coarse, insipid fish, and altogether destitute of the delightful

flavour of the common herring.

What is whitebait if it be not the young of the shad? Is it, then, a

distinct species? It would be easy enough to befool the public with an

absurd answer as to what whitebait is, because no writer, not the

ubiquitous Buckland himself, can successfully contradict another on almost

any point of fish-growth. When we see the transformation of the tadpole

into a frog, and the zoea into a crab, we need not be surprised at its

having been once prophesied that the whitebait turned a bleak, or the

assertion that it undoubtedly grows into a herring (clupea hargenus) and

if pressed for our reasons, we have a better answer to give than the young

Scotch ploughman, who, being asked how he knew that God had made him,

replied, after some little deliberation, that, “it was the common talk of

the country.” In many places where whitebait are captured, fishermen

believe them to be young herring—”herrinsile” they are called on the river

Clyde; and this idea has been ventilated by the author in the popular

periodicals of the day—it is an idea too that has long been common among

our fishmongers. That whitebait are young herring, or sprats in an

infantile stage, can be easily proved—on paper at least; and if our

Government had a fish laboratory, such as the French have at Concarneau,

the fact might very speedily be ocularly demonstrated. It is left, we

suppose, for either the Brighton or Crystal Palace Aquarium to determine

what fish the whitebait ultimately becomes, herring or sprat. There has

been a great amount of controversy as to the natural history of the

herring during late years, and so many curious facts have been educed,

that no one need be surprised to learn that whitebait are truly the young

of that fish. This may seem extraordinary; but without being dogmatic, it

may be permitted us to say that the points of resemblance between herring

and whitebait are wonderfully numerous and convincing, as well in the

outward appearance as the anatomical structure of the two fishes. At all

events the young of the shad and the true whitebait (at some places, such

is the demand, that all sorts of fry are “manufactured” into the latter

fish, there being so many who do not know one from the other) are very

different in many essential points as in the formula of the fin-rays and

the number of the vertebrae. Of course a young animal will change greatly

in appearance during growth. The whitebait, for instance, in common with

the sprat, has a serrated belly; but if it be the young of the herring, it

must grow out of that serration. It is elsewhere argued that, in the case

of the sprat, the bones protruding from the abdomen are ultimately covered

by the growth of the animal, and so gradually disappear.

Assuming “whitebait” to be young herring, we are entitled to ask at what

date the fish of that name, sold in London in June and July, were spawned.

The herrings at Wick, for example, are taken full of spawn up till the end

of the great fishery in August; at what time, then, if whitebait be young

herring, would those we can now eat at Blackwall be spawned? This, of

course, involves a surmise as to the rate of growth of the herring itself,

upon which question there has from first to last been much speculation,

many very dissimilar ideas having been propounded as to the period at

which the "poor man's fish" arrives at the reproductive stage. As we know

that there are different races of herrings coming to maturity at different

times, there ought to be no difficulty on this point, as the waters must

constantly contain fish of all ages, and it appears certain that the

whitebait of May and June cannot be older than the year ; it seems pretty

certain, also, that the sprat-sized herrings which begin to come to market

early in November are a little over a year old ; they were probably

released from their tiny shells early in the August or late in the July of

the previous year. It, is admitted by at least one competent naturalist,

that fry of the sprat may be seen in multitudes in July and August, when

they are of the length of two inches. We know, also, that young herrings

and young sprats are captured indiscriminately in the Firth of Forth in

the same shoals, of the same size, and presumably of the same age. In a

shoal of young herrings the sizes of the fish are exceedingly varied,

ranging from three to six inches in length, and of corresponding girth ;

some serrated, some not ; some weighing a quarter of an ounce, some nearly

an ounce. Were these fish all born at once ? How about the serrations ?

Again, a jar of whitebait from the Thames, received by the writer for

examination, contained specimens of all sizes ; some little more than an

inch long, while some were two or three inches. How old would these be ?

and were some of them serrated and others not ? The bellies being all

decayed, that point could not be determined in any of the specimens

received. February and March are the great months for the spring races of

herring to spawn ; so that the specimens of whitebait just alluded to

(there were other fishes besides the young of the herring and the sprat)

would be about three months old ; and by November they would in all

probability be grown to the average size of sprats. Young herrings of the

Moray Firth, spawned in August, can sometimes be seen inshore about

November, looking exactly like whitebait.

The blanquette of Normandy and Brittany did not look when examined-if it

was it that was placed before us-to be any other fish than our sprat in an

early stage of its life. It is curious that whitebait exhibit many of the

characteristics of the sprat, and particularly the strongly serrated

abdomen. That peculiar mark is held by some naturalists as good proof that

sprats never become herrings of any kind; if so, the same argument must

likewise hold good against the whitebait being the young of the herring ;

yet it is remarkable that the number of vertebra of both fishes, i.e. the

common herring and a portion of the whitebait, are the same, namely,

fifty-six, as are also the formula of the various fin-rays. But little

weight need be laid on this latter point; few writers give the same

figures about the fin-rays ; and as there are different kinds of herrings,

and different races of each kind, it is probable that there will be

differences in the number of fin-rays. What is harder to understand is the

fact that the vertebrae differ also ; these urn from forty-seven in the

sprat to fifty-six in the common herring, different numbers having been

found in the same race of herring. But whilst it maybe admitted, for the

sake of argument, that the smaller number might increase-i.e. that sprats

with forty-eight vertebra, might grow into herring with fifty-six

vertebra-it is quite clear that whitebait with fifty-six vertebrae will

never grow into sprats with forty-eight vertebrae ! The more the case of

the whitebait is studied, the more difficult it becomes to arrive at a

satisfactory conclusion. The earliest writer on whitebait that we know is

Pennant ; but when he wrote the whitebait was not a fashionable fish. It

was eaten then only by "common people" "the lower order of epicures" - and

the authorities, thinking that whitebait were the young or fry of some

large fish, "proclaimed" that it should not be taken. Pennant at one time

held the whitebait to be the young of the bleak, and Dr. Shaw followed

suit in his General Zoology; while Donovan held "that same" to be the

young of the shad. Donovan, blundering himself, "pitches into" Pennant for

his errors, maintaining that the industrious zoologist had never seen the

real whitebait. This latter idea is worth following up. Might not our

savans, now that the mysterious dish has taken its place on the rich man's

table, summon a congress to sit upon it? Were a general fishery congress

to be held, it would be well that specimens of the whitebait of different

rivers should be exhibited and reported upon; for the fish known as

whitebait at Blackwall may not be the fish known as whitebait at

Queensferry. In the case of the parr controversy, it was found that there

were parrs of many different members of the salmon family, which, as a

matter of course, greatly enhanced the difficulty of solution, as well as

setting the experimenters by the ears. The whitebait mystery is one of

those mysteries which many a dabbler in natural history will hold himself

able to solve; and yet those attempting to solve the problem may be all

working on different fishes. Any man who may know even a little about

fish, will have seen that the so-called dish of whitebait, served at a

fashionable tavern, is a varied mass of minnows, young bleak, infantile

sprats, and the fry of other well-known fish. So much for this tavern

celebrity !

Besides whitebait there are other mysterious

fish-especially in Scotland-which are well worthy of being alluded to. An

idea prevails in Scotland that the vendace of Lochmaben and, the powan of

Lochlomond are really herrings forced into fresh water, and slightly

altered by the circumstances of a new dwelling-place, change of food, and

other causes. One learned person lately ascribed the presence of sea fish

in fresh water to a great wave which had at one time passed over the

country. But no doubt the real cause is that these peculiar fish were

brought to those lakes ages ago by monks or other persons who were adepts

in piscicultural art.

A brief summary of the chief points in the habits of these mysterious fish

may interest the reader. The "vendiss," as it is locally called, occurs

nowhere but in the waters at Lochmaben, in Dumfriesshire ; and it is

thought by the general run of the country people to be, like the powan of

Lochlomond, a fresh-water herring. The history of this fish is quite

unknown, but it is thought to have been introduced into the Castle Loch of

Lochmaben in the early monkish times, when it was essential, for the

proper observance of church fasts, to have an ample supply of fish for

fast-day fare. It is curious as regards the vendace that they float about

in shoals, that they make the same kind of poppling noise as the herring,

and that they cannot be easily taken by any kind of bait. At certain

seasons of the year the people assemble for the purpose of holding a

vendace feast, and at one time large quantities of the fish were caught by

means of a sweep net; but of late years the vendace has been scarce; only

six were taken this year (1873). The fish is said to have been found in

other waters besides those of Lochmaben, but I have never been able to see

a specimen anywhere else. There are a great number of traditions afloat

about the vendace, and a story of its having been introduced to the lake

by Mary Queen of Scots. The country people take a pride in showing their

fish to strangers. The principal information I can give about the vendace,

without becoming technical, is, that it is a beautiful and very

symmetrical fish, about seven or eight inches long, not at all unlike a

herring, only not so brilliant in colour; and that the females of the

vendace seem to be about a third more numerous than the males-a

characteristic which is also observed in the salmon family. The vendace

spawn about the beginning of

winter, and for this purpose gather, like the herring, into shoals They

are very productive, and the young do not take long to grow to maturity.

The specialties of the Lochleven trout may be chiefly ascribed to a

peculiar feeding-ground, Feeding I believe to be everything, whether the

subjects operated on be cattle, capons, or carps. The land-locked bays of

Scotland afford richer flavoured fish than the wider expanses of water,

where the finny tribe, it may be, are much more numerous, but have not the

same quantity or variety of food, and, as a consequence, the fish obtained

in such places are comparatively poor both in size and flavour. Nothing

can be more certain than that a given expanse of water will feed only a

certain number of fish ; if there be more than the feeding-ground will

support they will be small in size, and if the fish again be very large it

may be taken for granted that the water could easily support a few more.

It is well known, for instance, that the superiority of the herrings

caught in the inland sea-lochs of Scotland is owing to the fish finding

there a better feeding-ground than in the large and exposed open bays.

Look, for instance, at Lochfyne : the land runs down to the water's edge,

and the surface water or drainage carries with it rich food to fatten the

loch, and put flesh on the herring; and what fish is finer, I would ask,

than a Lochfyne herring? Again, in the bay of Wick, which is the scene of

the largest herring fishery in the world, the fish have no land food,

being shut out from such a luxury by a vast sea wall of everlasting rock;

and the consequence is, that the Wick herrings are not so rich in flavour

as those taken in the sea-lochs of the west of Scotland. In the same way I

account for the fine flavour and beautiful colour of the trout of

Lochleven. This fish has been acclimatised with more or less success in

other waters, but when transplanted it deteriorates in flavour, and

gradually loses its beautiful colour-another proof that much depends on

the feeding-ground ; indeed, the fact of the trout having deteriorated in

quality as a consequence of the abridgment of their feeding-range, is on

this point quite conclusive. I feel certain, however, that there must be

more than one kind of these Lochleven trouts ; there is, at any rate, one

curious fact in their life worth noting, and that is, that they are often

in prime condition for table use when other trouts are spawning.

The powan, another of the mysterious fish of Scotland, is also considered

to be a fresh-water herring, and thought to be confined exclusively to

Lochlomond, where they are taken in great quantities. It is supposed by

persons versed in the subject that it is possible to acclimatise sea fish

in fresh water, and that the vendace and powan, changed by the

circumstances in which they have been placed, are, or were, undoubtedly

herrings. The fish in Lochlomond also gather into shoals, and on looking

at a few of them one is irresistibly forced to the conclusion, that in

size and shape they are remarkably like common herring. The powan of

Lochlomond and the pollan of Loch Neagh are not the same fish, but both

belong to the Coregoni : the powan is long and slender, while the pollan

is an altogether stouter fish, although well shaped and beautifully

proportioned.

I could analyse the natural history of many other fish, but the result in

all cases is nearly the same, and ends in a repeated expression that what

we require as regards all fish is the date of their period of reproduction

; all other information, without this great fact, is comparatively

unimportant. It is difficult, however, to obtain any reliable information

on the natural history of fish either by way of inquiry or by means of

experiments. Naturalists cannot live in the water, and those who live on

it, and have opportunities for observation, have not the necessary ability

to record, or at any rate to generalise what they see. No two fishermen,

for instance, will agree on any one point regarding the animals of the

deep. I have examined many intelligent fishermen during the last ten

years, and few of them have any real knowledge regarding the habits of the

fish which it is their business to capture. As an instance of fishermen's

knowledge, one of that body recently repeated to me the old story of the

migration of the herring, holding that the herring comes from Iceland to

Great Britain in order to spawn, and that the sprat goes to the same icy

region that it may fulfil the same instinct !

"Where are

the haddocks?" I once asked a fisherman. "They are about all eaten up,

sir," was his very innocent reply; and this in a sense is true. The shore

races of that fish have long disappeared, and our fishermen have now to

seek this most palatable inhabitant of the sea in deeper water. Vast

numbers of the haddock used to be taken in the Firth of Forth, but during

late years they have become very scarce, and the boats now require to go a

night's voyage to seek for them. If we knew the minutiae of the life of

this fish we should be better able to regulate the season for its capture,

and the percentage that we might with safety take from the water without

deteriorating the breeding power of the animal. There are some touches of

romance even about the haddock, but I need not further allude to these in

this division of my book, as I shall have to refer to this fish under the

head of the "White Fish Fisheries." The haddock, like all fish, is

wonderfully prolific, and is looked upon by fishermen as being also a

migratory fish, as are also turbot and many other sea animals.

The family to which the haddock belongs embraces many of our best food

fish, as whiting, cod, ling, etc. ; but of the growth and habits of the

members of this family we are as ignorant as we are of the natural history

of the whitebait or sprat. I have the authority of a rather learned Buckie

fisherman for stating that cod-fish do not grow at a greater rate than

from eight to twelve ounces per annum. This fisherman had seen a cod that

had got enclosed by some accident in a large rock pool, and so had

obtained for a few weeks the advantage of studying its powers of

digestion, which he found to be particularly slow, although there was

abundant food. The haddock, which is a far more active fish, my informant

considered grew more rapidly. On asking this mail about the food of

fishes, he said he was of opinion that they preyed extensively upon each

other, but that, so far as his opportunities of observation went, they did

not as a matter of course live upon each other's spawn ; in other words,

he did not think that the enormous quantities of roe and milt given to

fish were provided, as has been asserted by one or two writers on the

subject, for any other purpose than keeping up the species. The spawn of

sea-animals is extensively wasted by other means ; and fish have no doubt

a thousand ways of obtaining food that are unknown to man ; indeed the

very element in which they live is a great mass of living matter, and

doubtless affords by means of minute animals a wonderful supply of food.

Fish, too, are less dainty in their eating than is generally supposed, and

some kinds eat the most revolting garbage with great avidity.

It is a very common error that all fish are migratory. Some fishermen, and

naturalists as well, picture the haddock and the herring as being

afflicted with perpetual motion-perpetual wanderers from sea to sea and

shore to shore. The migratory instinct in fish, in my opinion, being very

limited. They do move about a little, without doubt, but not farther than

from their feeding-ground to their spawning-ground-from deep to shallow

water. Some plan of taking fish other than the present must speedily be

devised ; for now we only capture them-and I take the herring as an

example-over their spawning-ground, when they are in the worst possible

condition, their whole flesh-forming or fattening power having been

bestowed on the formation of the milt and roe. I repudiate altogether this

iteration of the periodical wandering instincts of the finny tribes. There

are great fish colonies in the sea, in the same way as there are great

seats of population on land, and these colonies are stationary, having,

comparatively speaking, only a limited range of water in which to live and

die. Adventurous individuals of the fish world occasionally roam far away

from home, and speedily find themselves in a warmer or colder climate, as

the case may be ; but, speaking generally, as the salmon returns to its

own waters, so do sea fish keep to their own colony. All they seem to need

is a rallying point-thus at any place where there is a wrecked ship in the

water, a sand-bank, or a chain of rocks, certain kinds of fish will there

be found assembled. Our larger shoals of fish, which form money-yielding

industries, are of wonderful extent, and must have been gathering and

increasing for ages, having a population multiplied almost beyond belief.

Century after century must have passed away as these colonies grew in

size, and were subjected to all kinds of influences, evil or good : at

times decimated by enemies, or perhaps attacked by mysterious diseases,

that killed the fish in tens of thousands. Schools or shoals of fish, when

they become of an extent that will admit of constant fishing, must have

been forming during long periods of time ; for we know that, despite the

wonderful fecundity of all kinds of sea-fish, the expenditure of both seed

and life is something tremendous. We may rest assured that, if a female

codfish yields its roe by millions, a balancing power exists in the water

that prevents the bulk of the eggs from coming to life, or at any rate

from reaching maturity. If it were not so, how came it, when there was no

fish commerce, and when man only killed the denizens of the sea for the

supply of his individual wants, that our waters were not, so to speak,

impassable from a superfluity of fish ? Buffon has said that if a pair of

herrings were left to breed and multiply undisturbed for a period of

twenty years, the result would be a bulk of fish equal to that ' of the

globe on which we live !