|

FOULA

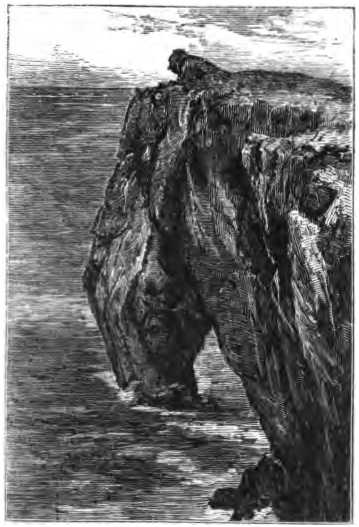

West Coast of Walls—Hivda-Grind

Bocks—Five Hills of Foula— Lum of Liorafield—Skua

Gull—Precipices—Myriads of Sea-fowl—Supposed Carbuncle.

THE coast from Sandness

southwards is singularly wild and rugged, consisting, as it does, of a

series of precipices, much tom up by the elements, and indented here and

there by deep gios. Over-topping them all (for none of the cliffs is

over 600 feet in height), the great hill of Sandness heaves its head

aloft. The only landing-place along this inhospitable line of sea-board

is at a small inlet, called Dale, from which a haaf-fishing is carried

on. This indentation in the coast is prolonged for a great distance

inland in the form of a deep glen, along whose steep sides several

well-tilled crofts are arranged. This sequestered toun of Dale is the

only place of human habitation on the great stretch of moorland which

separates Sandness from Walls.

The point of Wattsness

marks the termination of this line of coast, on the south. As it is the

nearest point on the mainland to the island of Foula, it may be well to

proceed thence to visit that romantic and solitary rock in the ocean.

The distance is eighteen miles, and the course south-west. Unless it be

the traveller’s good fortune to obtain a steamer—and they are by no

means numerous in these latitudes—the best conveyance to Foula is a good

six-oared fishing-boat. A sailing vessel is not so agreeable, for the

passage is beset with tideways; and calms and fogs are by no means

uncommon in the summer time—and no one who could help it would visit

Foula at any other season. About three miles from this island, in an

easterly direction, are the Hivda-grind rocks, a dangerous reef of

considerable extent. With low tides, when they are about four feet under

water, the tang which grows on them is distinctly visible above the

surface. In one or two deep depressions on the surface of one of the

largest rocks of Hivda-grind are several large loose boulders, which

seem to have lain there for ages. Whenever the sea is much agitated—and

it is never still—the boulders are set in motion, and by their friction

wear away the substance of the rocks and deepen the pools in which they

lie. These boulders suggest two curious questions, the one for the

geologist, the other for the hydrographer—viz., How came they there 1

and, Why are they not washed out of these basins, over the reef, and

allowed to sink in the deep water alongside?

As might be expected, the

Hivda-grind rocks are very dangerous to commerce, and several vessels

are known to have perished on them; how many others have shared the same

fate will only be known when the sea gives up its dead. The lofty island

of Foula, which may be seen, presenting the appearance of a dense blue

cloud, from every bill-top of any height in Shetland, now displays

itself more distinctly. It is about three miles long, and nearly two

broad. Its hills, divided into five conical peaks, occupy the western

portion of the island; while, along the eastern half, a plain, almost

level, runs from end to end. Its geological structure is almost

exclusively of sandstone. The best landing is at a little inlet, called

Ham, exactly in the middle of the island. All the inhabitants are, of

course, confined to the level plain.

The Foula hills are as

steep as they are high; and from whatever point it is commenced, their

ascent is a very arduous undertaking. Exactly opposite the

THE HORN OF PAPA.

little harbour of Ham is

the hill of Hamnafield, which terminates, on the west, in a sheer

precipice 1200 feet high. It is on the top of this peak that tradition

places the “Lum of Liorafield,” a narrow chimney leading to the

subterranean regions. So great is its depth that several barrels of

lines are said to have been let down through the “Lum,” without reaching

the bottom. Recent explorers have, however, failed to discover this

remarkable opening.

One of these hill-tops is

the breeding-place of the bunxie or skua gull. This beautiful bird, the

largest and fiercest of the gull tribe, builds no nest, but lays its

eggs and brings forth its young amongst the grass or heather, so that a

visitor can easily handle the young bunxies. If he does so, it will not

be with impunity, f6r the parent birds hover round, and, whenever

opportunity offers, pounce down upon the intruder with a sudden and

violent swoop. So near do they come, that, if his head is bare, tjie

skull of the visitor is in danger of being seriously injured by the

strong bill of the skua. If he is armed with a good stick, and is able

to use it adroitly, he can readily return the compliment by breaking the

wing of his feathered assailant. The bunxie is brown in colour, and has

a strong, sharp, well-hooked bill. Its body is two feet long, and the

wings, when extended, measure about six feet from tip to tip. This bird

is the terror of all the feathered race, and even the eagle has a

salutary dread of it. Save in the north of Unst, the skua is found

nowhere else in Great Britain. The proprietor of Foula very properly

gives his tenants strict orders for the protection of this truly rara

avis.

The whole west coast of

the island is one great line of gigantic precipices, from 1100 to 1200

feet in height. All we have hitherto examined, even those of Noss, are

as nothing compared with them. Everywhere along these giddy heights a

magnificent view is obtained of the various projecting points, which

diversify the cliffs; of the surging waters, which wash their feet; and

of the dense clouds of sea-fowl which darken the air and spread

themselves over the sea. One of these projecting points, used to be the

breeding-place of the white-tailed eagle, and its eggs were distinctly

visible through the great distance separating them from the spectator’s

stand-point at the top of the cliff. From another point farther north

than this, some rays of bright light can be seen at night, radiating

from the dark surface of the precipices. These were long believed to

proceed from a large and valuable carbuncle, but this supposition has

never been confirmed. |