|

Swarback’s Mine—Muckle

Roe—Busta—The Giffords of Busta.

PASSING the northern

mouth of Roe Sound, and sailing under the towering granite cliffs of

Muckle Roe—scooped out here and there into magnificent caves, once the

haunts of robbers and smugglers—we reach a strait, which rejoices in the

curious name of Swarback’s Mine. Lying between the islands of Roe and

Vemintry, it forms the common entrance to an important congeries of voes,

opening up a great extent of country. The Voe of Busta runs north, that

of Aith south; while Gonfirth takes a south-easterly course, and

Olnafirth stretches circuitously in the same direction, several miles

into the heart of the Mainland. The eastern shores of Mnckle Roe are

low, fairly cultivated, and well sheltered by the land-locked bay. The

Sound between that island and the Mainland is navigable only by boats;

and so narrow and shallow is it, that, at low tides, the people can wade

across. Small as it may appear, Muckle Roe is twenty-four miles in

circumference.

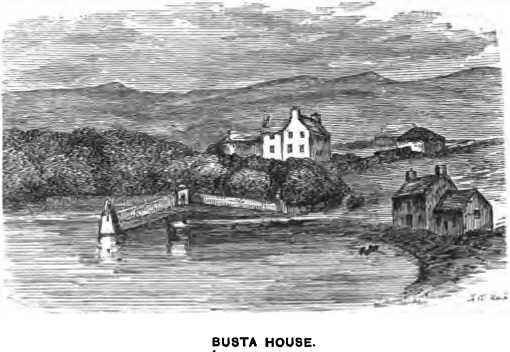

Having passed the

opening, we skirt along a fine green ness, and soon reach Busta—a place

which has for generations figured largely in Shetland history. Than its

situation, none more favourable could have been selected. Nature has

scooped out an amphitheatre in the hill-side, with a small circular

branch of the Voe at its base. Not many feet above the water’s edge,

rises the good old mansion of Busta, embowered in trees. The

productiveness of the gardens, once so fertile, has been seriously

impaired by their overshadowing influence. Many of these trees are

native, and the*perfection they have here attained is evidently due to

the rich soil, sheltered situation, and the protection of high walls.

The grounds of Busta are laid out in the straight Dutch style of last

century. This arrangement is particularly observable in the Willow Walk,

the principal avenue leading to the house from the county road. It runs

straight as an arrow, for several hundred yards, through a ravine. The

trees have grown so much over the road that the stranger must take care

to avoid the fate of a learned divine—now no more—who, on riding through

the avenue, encountered one of John Gilpin’s mishaps, and involuntarily

hung, not his harp, but his hat and wig, on the willow tree.

The principal entrance to

the house of Busta is through a baronial-looking hall, with a massive

stone staircase. Over the doorway, which looks towards the gardens, is

the coat of arms of the Giffords. Beyond the entrance the house has no

pretensions to architectural embellishments. It consists of three

distinct portions, each erected at different periods since the beginning

of last century. The drawing-room and dining-room are adorned by many

fine family portraits, the most of which were executed by a native

artist, Mr John Irvine.

The Giffords of Busta

have rather a romantic history. Like several other families of Shetland

lairds, they spring from a clergyman. This gentleman was minister of

Northmavine at the Reformation. His descendants prospered, and acquired

a considerable estate, which, however, being divided amongst the

different members of a large family, became so atomised as to be of

little use to any one. In the beginning of last century arose Thomas

Gifford, a man of great sagacity, energy, and business talent. He was a

Whig and a Hanoverian, while all the other Shetland lairds were Tories

and Jacobites. This circumstance gave him great political influence in

the troublous times of the two rebellions. The Earl of Morton appointed

him Steward-Depute of the county. To the occupation of proprietor and

chief-magistrate he added that of a merchant, and appears to have got

most of the trade of the islands into his own hands. With these

advantages he soon consolidated the family property, absorbed many

neighbouring lands in it, and, in course of time, accumulated the

largest estate in Shetland. Everything seemed to prosper with Mr

Gifford. Not only was he rich and powerful, but the sun of domestic

happiness shone on him. He was the husband of an accomplished spouse, a

daughter of Sir John Mitchell, of Westshore, Baronet, and the father of

four promising sons. But human happiness, ever evanescent, proved

particularly so in his case. One dire day in 1748, Busta’s four sons,

accompanied by their tutor, went to visit their uncle, who was

chamberlain to the Earl of Morton, and lived at Wethersta, on the’

opposite side of the voe. The young men spent a pleasant evening, and

were returning as they came, when, horrible to relate, the boat was

upset, and they all found a watery grave. Wonderfully did the good laird

bear up against this fell blow, which left him childless, and without an

heir in his old age. He found his consolation in the words, “The Lord

gave, and the Lord taketh away; blessed be the name of the Lord."

When the first outburst

of sorrow was over, some rays of hope began to dawn on the bereaved

family. Mrs Barbara Pitcairn, a humble relative, who lived in the

household, began to give promise of a coming child, and declared she had

been privately married to John Gifford, the eldest of those who were

drowned. In due time she gave birth to a son. The good old laird was

soon afterwards gathered to his fathers, and left the estate to the able

management of his widow, Lady Busta. Her young grandchild, Gideon

Gifford, was brought up as heir, and, eventually entered on possession

of his wide domain, which he enjoyed all his lifetime, no one

questioning his right. Mr Gideon Gifford appears to have lived in great

style, assuming all the pomp and display of a great Highland chief, and

certainly not adding to the value of his estate. He died in 1812, and

was succeeded by his eldest son.

Arthur Gifford, Esq. of

Busta, was no ordinary country squire. To great natural abilities, and

no mean scholarship, he added a very handsome face and form, a-

commanding presence, and most pleasing and highly cultivated manners.

Although by no means bound with them, his estate being entailed, he very

chivalrously became responsible for his father’s debts. He held his

extensive patrimony undisturbed for twenty long years. In 1832, the

representative of a remote branch of the family, settled in America,

raised an action in the Court of Session, with the object of having

himself served heir to Busta, on the ground of Gideon Gifford’s alleged

illegitimacy. A long and tedious proof was led, eminent counsel

retained, large numbers of elderly men and women, cognisant of the

circumstances, had their old age enlivened by a trip to Edinburgh, there

to give evidence in the Parliament House, and, as a necessary sequence,

great expense was incurred. The laird’s chief defence consisted in the

production of marriage lines, said to have been found in John Gifford’s

pocket after his dead body had been brought on shore in 1748. The

circumstance that the property had been in the undisputed possession of

the defender and his father, for eighty years, weighed greatly in his

favour. Still the evidence on the opposite side was strong, and the jury

wavered. At length they came to a decision in favour of Mr Gifford.

Amid the congratulations

of his friends and tenantry, the good laird once more took possession of

his patrimonial mansion, but the estate was fearfully burdened with

debt. Most' nobly did he bear up against such difficulties. He lived

amongst his people, kept up his dignity, was lavish in his hospitality,

enjoyed the. respect and good-will of every one, all the while managing

his property so well as to pay off a portion of the debt each year. But

a stroke of apoplexy came in the spring of 1856, and took the good old

man to his long home. The present representative of the family is his

niece, Miss Gifford of Busta, who resides at the manor house of that

name.

The estate of Busta

includes three-fourths of Northmavine, the half of Delting, besides

smaller portions of land in Walls, Aithsting, and Yell. The rental for

the year 1872-73 is stated in the Parliamentary returns of 1874 to be

£2707. The sum may not seem large, but it takes an immense extent of

poor Shetland soil to bring in such a revenue. |