Now what was this mediaeval

system of trading under which the free or royal burghs like Edinburgh

enjoyed so many trade privileges, and which placed so many restrictions on

the commercial activities of " unfree" towns like Leith. But

before we can answer that question we must know what is meant by a free or

royal burgh like Edinburgh on the one hand, and an unfree town like Leith

on the other.

In our story of how the De

Lestalrics became possessed of the barony of Restalrig we found that under

the feudal system there were tenants-in-chief, or great, or king’s

vassals, who held their land from the king. But the king kept much land—the

royal demesne or domain it was called—in different parts of the country

in his own hands, and, just as the great vassals built on their estates

castles or peel towers for defence, round whose sheltering walls villages

and towns gradually arose, so the king had castles like that of Edinburgh,

and under the shadow of their protecting walls towns also grew up. The

name burgh—a word which means a castle, a walled town or stronghold—-as

especially given to those towns that grew up round a castle, whether of

king or noble.

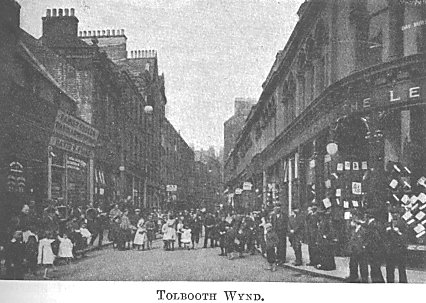

In those distant days, when

merchants transported goods from one part of the country to another, a tax

called toll had usually to be paid to the overlords of the baronies

through which the goods passed; and, in the purchase or sale of

merchandise in any town or market, another tax or toll called customs had

to be paid at the tolbooth of the town. A tolbooth, although it became

much more in later centuries, was at first simply the building where these

taxes or customs were paid, and for that reason Wycliff’s Bible tells us

that Jesus called Matthew "sitting at a tolbooth," and most

Scots towns have a Tolbooth Wynd, where the tolbooth once stood, as in

Leith, or where it still stands, as in the Canon-gate, Edinburgh.

All towns were either part

of the royal domain, and were for that reason known as royal burghs, and

had the right of trading anywhere throughout the land without paying toll;

or were part of the barony of some noble, abbot, or bishop, in which case

they were called burghs of barony, and had no such trading rights. If a

burgh rose a step higher than the burghs of barony, and approached the

privileges the royal burghs possessed in trading anywhere within the land

exempt from toll, it was designated a burgh of regality. Edinburgh with

its king’s castle was a royal burgh; the Canon-gate, which had grown up

under the fostering care of the Abbot of Holyrood, was, by the charter of

David I., a burgh of regality; and Dalkeith was a burgh of barony; but

poor Leith seems to have been the Cinderella of Scots towns, for as a town

it never was a burgh at all until it became a parliamentary burgh in 1833.

Burghs of barony and burghs of regality, while enjoying much more freedom

than Leith, were more or less largely under the control of their

overlords, and were, therefore, called "unfree" towns. As the

king could live only in one of his castles at a time, the royal burghs

were, to a very large extent, left to look after themselves. They had the

great privilege of self-government—that is, of choosing their own

bailies and making their own laws. They were, therefore, known as

"free" burghs.

The rise of these free

burghs under the protection of the royal castles, where merchants could

buy and sell and craftsmen follow their calling under the protection of

their own burgh Laws, was really the beginning of progress and

civilization in Scotland as in every other country. To carry on trade and

manufacture goods requires capital; and no man can gather capital or goods

and hand these on to his children if they are to be carried off by his

overlord at his death. No trading class could arise at all until this

privilege of inheriting property was secured, and this right was only

completely enjoyed in the king’s free burghs. When David I., therefore,

conferred upon Edinburgh the great privileges of a royal burgh he began

commerce in our district, and started Leith on its career as a seaport.

To-day any one may trade

freely, both at home and abroad; but in the far-off days of David I., and

for many long centuries after, this privilege belonged to the merchants of

free burghs only, and the country was divided into areas, in each of which

a royal burgh had the monopoly of trade. Indeed, these early Scottish

burghs seem to have been the only places in which trade could be lawfully

carried on, and from the inhabitants of "unfree" towns like

Leith, to whom they conceded any trading rights, they exacted toll, as the

trade guilds of Edinburgh did from those of Leith, for in early mediaeval

times no person could even follow a craft or trade outside a free burgh.

This was also the early law of England, and indeed of all Western Europe.

But as wealth grew and trade increased, these trade monopolies and trade

restrictions became very vexatious, and the Leithers, therefore, under

certain conditions, had to be allowed to open shops and sell goods with

the least possible interference with the trading rights of the royal and

free burgh of Edinburgh.

The district over which

Edinburgh had this monopoly of trade was the Sheriffdom of Edinburgh,

which stretched from the river Almond on the west to just beyond Levenhall

on the east. Beyond Levenhall was the trade district of the royal burgh of

Haddington, while on the west, across the Almond, was the trade precinct

of the equally free burgh of Linlithgow.

But this complete control

over the home trade was not the only privilege of royal burghs. They had

one more at least equally great—the sole monopoly of carrying on foreign

trade. None but the merchants of free burghs could engage in oversea

trade. The trading powers of other burghs extended only to the right of

providing themselves in the markets of the free burghs with the foreign

and other produce which these favoured towns had imported, and of

retailing this in their own districts, and to holding a weekly market and

a yearly fair.

Of course Edinburgh had (as

it still has) its weekly corn market and its Hallow Fair, held at the

season of Hallow E’en. On these market days in Edinburgh the country

people from the surrounding district, including Leith, brought for sale

the produce of their farms, their poultry,

butter, eggs, and cheese, but had to set up their stalls on the

opposite side of the street from those of the citizens. There is still a

lingering remnant of this ancient weekly produce market to be seen every

Saturday morning in the High Street, just below the Tron Church, where

toll is still charged for the stance as was the custom in the Edinburgh of

long past days.

Here, again, Leith appears as the

Cinderella of Scots towns, for she had no regular weekly market, and

certainly never had a fair, and, although she was for centuries the most

important seaport in Scotland, no Leither was allowed any share in the

overseas trade of his own town. He could neither export any goods to, nor

import them from, foreign countries. Such trade in our district was the

monopoly of the merchant burgesses of Edinburgh only.

Nor was any foreign produce allowed

to be sold in Leith. An old Scots Act of Parliament declared "that no

man pak nor peill "in Leith—that is, trade nor traffic in Leith. If

Leithers wished to purchase any foreign produce they could only do so from

Edinburgh merchants at the Cross of Edinburgh. Leithers might own or man

the ships as mariners ; they could be "pynouris" (the old Scots

name for a dock labourer), but they could not otherwise share in the

foreign trade of their own town. Such was the law of the land as enacted

by the old Scots Parliament. Such a law could only be passed in a

Parliament where the burgesses of royal burghs had representation and the

inhabitants of unfree burghs had not. It was unjust, although few, if any,

saw it exactly in that light in those times, for it supported the utterly

selfish policy of giving commercial privileges to the inhabitants of royal

burghs from which the rest of the nation were shut out. Such a commercial

policy ruled the trade relations between Edinburgh and Leith in some

respects down to 1833, when Parliament made Leith a separate burgh.

Before a foreign-bound ship could

leave the harbour of Leith its cargo had to be shipped in the presence of

Edinburgh officials, who were usually members of the Town Council,

including the Town Clerk, the Water Bailie, and the Dean or head of the

Merchant Guild, who closely inspected each bale of goods taken on board.

Only the goods of the merchant burgesses of Edinburgh were allowed to be

shipped, and the owners, the skippers, and even the passengers had to

receive a certificate (" the baillie’s tikket

") before they were permitted to set forth on

their voyage. The regulations regarding incoming vessels from abroad were

equally strict. On the arrival of a vessel in Leith its cargo had to be

landed on the Shore, and nowhere else. Here it was carefully examined by

the same city officials, who put a value upon it, for in those days the

price of goods was settled by the Town Council along with the merchants at

the Tolbooth, to which the merchants had to bring their cargoes, and not

by competition in the open market— that is, by the law of supply and

demand. This control of prices was very necessary in those days, when all

trade was the monopoly of the guilds.

The cargo was then transported to

the Market Cross of Edinburgh, for the purchase and sale in Leith of any

imported goods was, as we have already seen, contrary to law. At the Cross

they were sold to the merchants of Edinburgh, who, in turn, sold them to

the people of Leith as they had need, for "all sic merchandice sould

first cum and be presented to the burgh of Edinburgh, and thairefter sould

be bocht fra the fremen thairof." Such was the law of the land as

enacted by the old Scots Parliament,

which was no doubt largely influenced by the advice of its burgess

members, who from the later years of Bruce’s reign had been sent there

as representatives of the interests of the royal burghs. The other burghs,

including unfree towns like Leith, had no parliamentary representation.

The royal burghs thus kept

the control of all trade in their own hands as far as they possibly could,

and, of course, for their own benefit alone. It was a highly selfish

policy, and was carried out with the most jealous and vexatious

interference with all who dared to trespass upon their privileges. But

that it was not so regarded in mediaeval times is shown by the fact that

this same commercial policy prevailed in a more or less narrow manner

among all the nations of Western Europe for centuries. It must therefore

have seemed to them the one best suited to the conditions under which they

lived, and indeed, when we have learned something of these social

conditions, we shall, perhaps, come to the conclusion that the privileged

royal burghs were not quite so selfish in their trade policy as at first

sight appears.

The Leithers, although not

free from the same narrow notions where their own interests were

concerned, not unnaturally looked on Edinburgh’s regulations restricting

their trading activities as unjust, and did not hesitate to evade them

when opportunity offered. The merchant burgesses of Edinburgh, on the

other hand, who never looked at trade questions from any but their own

class point of view, held fast by the privileges the law and their own

charters conferred upon them, and were jealously watchful for any breach

of them by the unfreemen of Leith. There was therefore constant bickering

between the two towns; indeed, it would have been strange had it been

otherwise. It is to the narrow and selfish trade policy of medieval times,

therefore, that we must look for the beginnings of that jealous feeling so

long existing between Edinburgh and Leith, which left a legacy of

suspicion that has not yet quite died out.

Down to 1597, when James

VI. brought Scotland into line with other countries in the matter of trade

policy, no duties, except, of course, local harbour dues, were charged on

imports. Scotland’s import trade was therefore conducted on a free trade

policy. But in old-time Scotland they believed in making "the

foreigner pay" by charging him duties on what was taken out of the

country, that is, on exports. These duties were known as the "great

Customs." From the customs duties on exports was derived the greater

part of the royal revenue, and for this reason, if for no other, foreign

trade had to be so regulated that the king should not in any way be

defrauded of his Customs duties.

It was for this reason that

foreign trade was restricted to the royal burghs and their seaports under

the king’s own immediate rule. In all such towns officials known as

"custumars" were appointed, whose duty it was to collect the

king’s customs the persons chosen being usually two of the leading

merchant burgesses of the burgh. It was the duty of these custumars to see

that no goods were shipped to foreign countries without the payment of the

fixed duties, and only when these were paid did the owner receive the

"baillie’s tikket," which allowed him to proceed on his

voyage. Had foreign trade in that age been open to all and sundry who

wished to engage in it, it would have been impossible with the limited

means of those days to control the collection of the export duties for the

king’s revenue.

Even restricted as the

foreign trade of the country was in the interest of the king and the free

burghs, we find James IV. declaring in 1506, "We are greittumlie

defraudit in our customes through pakking and peiling (that is, buying and

selling) of strangearis (that is, foreigners) guidis in Leyth unenterit to

our burgh of Edinburgh." You remember that all foreign imports

immediately they were landed on the Shore were transported to Edinburgh,

and there only could Leithers purchase them, not from the "strangearis"

who brought them, but only from the merchants of the city who bought them.

Now, judged by the conditions under which we live today, such a law seems

harsh and tyrannical; but it was not really so except in the high-handed

way in which it was sometimes enforced, as the Leithers knew very well,

although they might do their best to evade it.