|

ABOUT one hundred and fifty years after the departure

of the Romans from North Britain we find our country divided among four

nations. The Picts held all the territory north of the Forth and Clyde

save Argyllshire, which was held by the Scots, while the Britons occupied

Strathclyde, the territory between the Clyde and the Solway, and the

Angles held the south-east of the country, their territory stretching from

the Firth of Forth across the Cheviots into what is now England. Until

these four nations became one our country could never hope to prosper, for

the Picts, Scots, and Britons waged constant wars against the Angles of

Lothian, as that part of their territory between the Forth and the Tweed

was called, and they were also frequently at war with each other.

One of the greatest forces in aiding the work of

progress and civilization was Christianity, which, more than the wars of

ambitious chiefs and kings, helped to bring about the union of the

different peoples who occupied North Britain. It was St. Columba and his

earnest and tireless missionaries from Iona—the Holy Island of the west—who

evangelized all the land north of the Forth, while monks like St. Cuthbert

brought all the country south of the Forth to a knowledge of the Gospel.

At length the Picts and the Scots united into one nation, and in 1018

Malcolm II., their king, brought Strathclyde and Lothian also under his

rule. Our country had now become united, and from this time forward is

known as Scotland. With Malcolm II’s acquisition of Lothian in 1018

Leith became a part of Scotland, of which for so long it was to be the

chief seaport.

Of Leith before 1018 we know very little for certain.

Of the Leith of two or three centuries later we can form a more accurate

picture. There were then, as now, two Leiths—North Leith and South

Leith; but whereas in our day these two are parts of the same town, the

Port of Leith, they were quite separate and distinct places in those

far-back times. One point of likeness there was between them, and that was

that neither of them was allowed to manage its own affairs. North Leith

was governed by the abbot and monks of Holyrood Abbey, founded by David I.

in 1128, while the destinies of South Leith lay in the hands of the lairds

of Restalrig. It is difficult to realize these facts. The little village

of North Leith has grown into a busy, bustling port, while of the great

Abbey Church of Holyrood which ruled it only a part remains, and that a

roofless ruin. The little South Leith of those days, not considered large

enough to have a church of its own, is now a great and thriving town,

while Restalrig, its old-time superior, is to-day a mere hamlet, soon to

disappear before the ever-extending city, which even now has invaded its

village street. What strange changes the whirligig of time brings about

Besides founding the Abbey of Holyrood David I. richly

endowed it with lands and other gifts. In the Abbey’s great charter of

1143 there is engrossed a long list of the many possessions bestowed upon

it by its royal founder, and among these are the lands of North Leith and

that part of South Leith which now extends from the present Coalhill to

the Vaults. These lands, along with those of South Leith, then formed part

of a wide area round the mouth of the river known as Inverleith, and are

designated in the Abbey charter "that part of lnverleith which is

nearest the harbour." These words would seem to show that even at

this early date Leith had started on its career as a port. The shortened

form of the name, Leith, early became specially applied to the town, while

the longer form, Inverleith, like the name Inveresk at Musselburgh, was

restricted to the lands farther up the river.

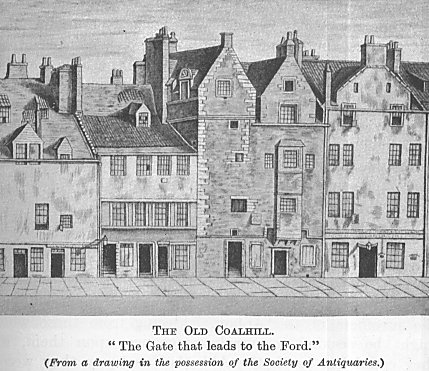

North

Leith must have been a tiny village in those days, for long centuries

afterwards it contained only seven hundred inhabitants. The Coalhill was

then a pleasant road with the cottages of the abbot’s tenants embowered

amid their apple orchards. The Water of Leith at this time flowed as a

full stream between grassy banks sloping down to the water’s edge. On

these banks stood the little village, its outline reflected in the clear

water, while on the edge of the stream were the fishers’ clustered

cottages, made of timber or unsmoothed stone, with roofs of straw, or of

heather of which so much grew near by. North

Leith must have been a tiny village in those days, for long centuries

afterwards it contained only seven hundred inhabitants. The Coalhill was

then a pleasant road with the cottages of the abbot’s tenants embowered

amid their apple orchards. The Water of Leith at this time flowed as a

full stream between grassy banks sloping down to the water’s edge. On

these banks stood the little village, its outline reflected in the clear

water, while on the edge of the stream were the fishers’ clustered

cottages, made of timber or unsmoothed stone, with roofs of straw, or of

heather of which so much grew near by.

It was the duty of the inhabitants of North Leith to

supply the abbot and canons with fresh fish, so generally eaten in

Catholic times with their many fast days on which meat was forbidden.

Their training as fishermen made them

excellent sailors for manning the abbot’s ships, and down to the present

day North Leith has always been noted for its hardy and skilful mariners.

As the people of North Leith paid their rents to the

abbot mostly in fish and farm produce, there was much coming and going

between the Abbey and the little village. There were only two ways

of approaching Holy-rood from North Leith. One was by the ford at

Bonnington, from which in our own day an old and narrow way still leads to

the later Newhaven Road. The other was by a ford at Old Bridge End, when

the street now known as the Coalhill had the somewhat lengthy name of

"the gate (= street) that leads to

the ford."

Here there was also a ferry, where the people were

taken across by boat when the water flowed smooth and deep at full tide.

This ferry we may call the Abbot’s Ferry, for to the Abbot of Holyrood

went most of the dues paid by those who crossed to and fro. Near Holyrood

Abbey there still exists a quaint and picturesque little building,

strangely misnamed Queen Mary’s Bath. As it stands just where the two

ancient roads from the Leith and Broughton districts converge upon the

Abbey it may have been a porter’s lodge to a side entrance much used by

the constant traffic between the Abbey and its possessions at Canonmills,

Broughton, Bonnington, and North Leith.

While the Abbey Church was especially built for the use

of the abbot and canons, the people of North Leith along with the other

vassals of the abbot were allowed to worship in the nave along with the

lay brethren or servants of the monastery, while they themselves used the

choir. No doubt the somewhat inconvenient isolation of the inhabitants of

North Leith was often pleaded by them as an excuse for their

non-appearance at Mass in the Abbey Church along with their

fellow-vassals.

The abbot had the power of dispensing justice in the

Abbey Court held in his tolbooth in the Canongate, and of inflicting

various pains and penalties on those of his Leith vassals who broke the

law. On the other hand, those same vassals had the right of sanctuary

within the precincts of the Abbey. Fleeing from those who might be seeking

to wreak vengeance upon them, if they could but reach the Abbot’s

Sanctuary they were safe. None might dare to lay hands upon them there.

The bounds of the sanctuary were anciently marked by four girth or

boundary crosses at the cardinal points. But these, like so many other

pre-Reformation monuments, have long since disappeared. The site of the

western cross, which stood at the foot of the Canongate, opposite the

outer gate of the Abbey, is marked by a circle of stones intersected by a

cross set in the causeway, while the site of the sanctuary boundary on

this side is to-day marked by the letter S set in lead in the

causeway at three different places.

But, after all, down to the beginning of the nineteenth century North

Leith occupied but a backwater in the stream of Leith’s history. The

real Leith, the Leith of history, was South Leith.

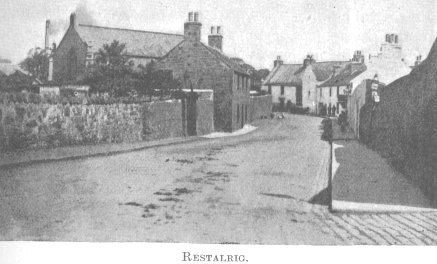

In those early times South Leith consisted of little more than a line

of houses facing the Water of Leith, and stretching as far as the Broad

Wynd, which was then waste land bordering the beach. It was quite

surpassed in size and importance by Restalrig. Both were parts of the

barony or estate of Restalrig, but it was Restalrig, and not Leith,

which gave its name to the barony and to the family, the De Lestalrics,

who owned it. We hear of this family as barons of Restalrig in 1198, some

fifty years after David I’s death, when the name comes into history for

the first time, the name of Thomas de Lestalric appearing in a Dunfermline

Abbey charter of that date. Thomas de Lestalric seems to have been a man

of influence in his day, for in 1210 we find him Sheriff of Edinburgh, a

sheriffdom that was co-extensive with Edinburgh’s trading precinct as a

royal burgh, for it extended from Levenhall beyond Musselburgh on the east

to the river Almond on the west. Thomas de Lestalric, like most Normans,

was a good friend to the Church, and bestowed upon it, among other gifts,

the lands of Coatfleld, thus showing this local place-name to be more than

seven hundred years old. It is probably derived from the Saxon word

"cote" meaning a sheepfold. In the charter conveying these lands

of Coatfleld to the Abbey of Inchcolm we have the earliest mention of any

townsmen of Leith in the names of Robert Hood, Baldwin Comyn, and Ernauld,

who seems to have had no surname.

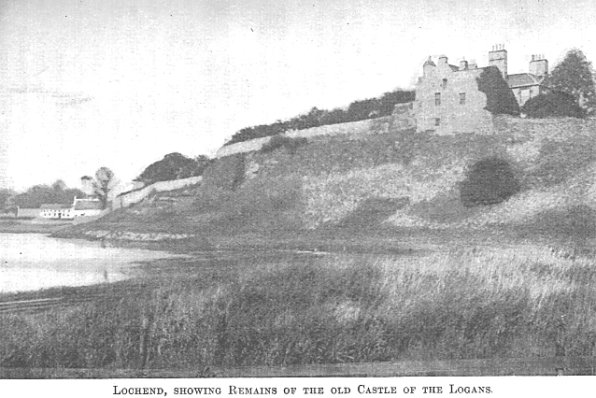

Thomas de Lestalric, however, was not the first owner

of the barony of Restalrig, for from the Dunfermline charter we find that

he had succeeded his father Edward. How many generations of this family

had held the barony before Thomas and his father Edward we do not know.

But the first De Lestalric is generally understood to have been one of

those Norman adventurers who came to seek fortune in Scotland about the

time of David I., and took his surname from the barony gifted him by the

king. When this first De Lestalric received as his domains all the South

Leith and Restalrig districts, he built his stronghold on the craggy

height overlooking the waters of Lochend. This castle of the De Lestalrics

has, of course, long centuries ago disappeared amid the cruel and

devastating warfare by which

Scotland was so often desolated. The ruins still to be seen rising above

the waters of Lochend are not part of the castle of the Dc Lestalrics, but

of the home, partly castle, partly mansion, of the Logans, their

successors in the barony.

Either Edward de Lestalric or his son Sir Thomas, whom

we have already mentioned, built a new church in the improved Norman style

of architecture, and this church was, of course, erected, not in South

Leith but in Restalrig, the most important part of the barony. It was at

this time that the estate or manor came to be recognized as a parish, and

the new church as the parish church. To this parish church at Restalrig

for many centuries the people of South Leith went to worship, as of course

did also the inhabitants of Restalrig and the rest of the barony owned by

the De Lestalrics. Later on this church gave place to the church that

stands in Restalrig to-day, and South Leith about 1488 came to be

possessed of a church of its own.

The twelfth-century village of South Leith was very

different from the picturesque country villages of our time, with their

neat cottages, each with its shining windows decorated with flowers and

snow-white curtains. In the twelfth century cottages had no windows, not

even window openings, the chimney hole in the roof and the open door

admitting all the light required. Yet they were not so comfortless to our

forefathers as they might seem, for life in those days was lived in the

open air much more than in ours. Mothers did their cooking and washing and

many other household duties in the open before their doors, and the

village street served as workshop for the village smith and carpenter.

The inhabitants of South Leith mostly found their

employment in tilling the fields that, with moor and woodlands, filled all

the land between Edinburgh, Restalrig, and Leith; and even centuries

later, when Leith had grown from village to town, its inhabitants still

derived much of what wealth they possessed from farming. From their

fields, and their few cattle, sheep, and swine, or from those of their

neighbours, came their food and clothing, and not from cargoes brought in

from abroad. But you must put from your mind all notions of the farming of

to-day. Then there were no great farm steadings with their hinds’

cottages dotted over the land; there were no farm labourers working for

wages as with us to-day. Instead of wages, each had so much land, which he

tilled for his own use, and in return helped to farm his overlord’s land

as well. There were in those days two classes of tenants—the free and

the unfree or villeins as they were called. All paid their rent by service

of some kind in accordance with the feudal system—the free mostly by

military service and certain dues either in money or in kind (that is, in

farm produce to feed his lord and his retainers), and the unfree by

helping to till the lands of De Lestalric as well as their own holding.

But ere many centuries had passed all the folks around Leith gradually

became free tenants, and the service on the overlord’s lands became

simply a part of the rent of the holding which might be done by a hired

labourer.

This old custom of rendering so much service as part of

rent, and especially rent of land, lingered among us for centuries after

this time, for in 1640 the feu-duty of a house in the Kirkgate opposite

South Leith Church was forty pence Scots and one day’s work in autumn—

that is, in the harvest fields of the Laird of Restalrig. We would find

similar conditions attached to the feus of other old houses in Leith could

we but get a peep at their old feu-charters, where such still exist.

But the landscape of those centuries differed from ours

in a more striking way than merely in the absence

of farm steadings and their cottages. In these times

the land was unenclosed. There were no hedges or dykes dividing it up into

separate fields. The land all round Leith formed one great tract divided

by balks of turf into strips or rigs. Most of its inhabitants had a

certain number of these strips, according to the size of their holdings,

but instead of the strips belonging to one person all lying adjacent to

each other they were scattered all over the district, no two being

together. Remains of this open-field system still linger among us. The

fields of Lochend farm to-day form three huge tracts. The first around the

loch once occupied the whole area between the Lochend and Easter Roads,

the second stretches from the Lochend to the Restalrig Road, and the third

from the latter road to the Craigentinny Meadows. Leith was like one large

farm.

It is evident that these strips could not be ploughed

separately. The great fields composed of these strips had to be farmed by

the joint labours of all their holders working together. Each farmer had

therefore to cooperate with his neighbours in the work, and had to farm

exactly as they did. That is why this wasteful, Unscientific, open-field

system of farming continued through so many centuries. The great wooden

ploughs, the joint property of all the farmers, were drawn by teams of

from four to eight oxen.

This system of farming prevailed in our district, and

indeed all over Scotland, down to the middle of the eighteenth

century, when fields began to be enclosed by hedgerows, and large farm

steadings began to come into fashion. The two great fields on either side

of Restalrig Road are relics of the old open-field system of farming. The

names of all the farmers of these old open-field days in the Leith and

Restalrig districts, with the size of their holdings and their shares in

the ploughing, are recorded in manuscript records still existing. This system of farming prevailed in our district, and

indeed all over Scotland, down to the middle of the eighteenth

century, when fields began to be enclosed by hedgerows, and large farm

steadings began to come into fashion. The two great fields on either side

of Restalrig Road are relics of the old open-field system of farming. The

names of all the farmers of these old open-field days in the Leith and

Restalrig districts, with the size of their holdings and their shares in

the ploughing, are recorded in manuscript records still existing.

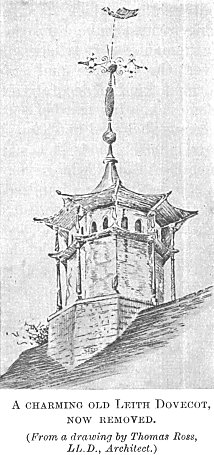

The times, seasons, and methods of farming were

determined at an open-air meeting of the local farmers known as the Burlaw

Court, held fortnightly in the Doocot (Dovecot) Park, on the farm of

Newmains, whose fields were where

Hermitage Place and the adjacent terraces stand to-day. In those days

every barony had its dovecot. In cold and stormy weather this Burlaw Court

bad its meeting in Clephand’s Tavern at

the townend, a site now covered by the tenements near what was once the

Watt Hospital or aImshouse, and now utilized as a temporary school.

The great stone dovecot of the Logans of Coatfield

disappeared, as did the Burlaw Court itself,

in the second half of the eighteenth century, to make way for the houses and gardens of Hermitage

Place. Yet the land on which it stood, so long and so familiarly known

as the Doocot Park, has never been without dovecots from that time till

now, for several f the dwellers here in days gone by, either from adherence

to ancient custom or because of their added charm, had pigeon-cots erected

in the gardens behind their houses.

The delightful dovecot shown in the accompanying

illustration, a fitting ornament to the garden at 1 Hermitage Place which

it once adorned, for it survives no longer; must have been designed and

constructed by a craftsman of rich artistic gift. Another that lacks,

however, the elegance and grace of the one pictured here forms a kind of

decorative finial to the summer-house of a neighbouring garden. It is many

long years since pigeons sheltered here, and the dovecot itself much

overgrown with ivy is "wearin’ awa’" like the old Leith

merchant family who have owned the house behind which it stands for over a

hundred years, and with whom stories of the birds that once fluttered

around it are still cherished memories.

Beyond the cornfields lay the pasture lands and the

waste, stretching away to merge in the Figgate Whins, which extended to

near Musselburgh. These pasture and waste lands were at least as valuable

as their arabic corn land, for in those early days people depended as much

on their cattle, sheep, and swine for food as they did on their corn. The

waste land was covered with whins and heather and patches of woodland,

where the sheep and cattle grazed, and the swine and geese "found for

themselves," for they fed on many things which other animals refused.

Here also the Leithers gathered wood, and in autumn dug their peats for

winter fuel.

The common grazing ground for Leith was the Links, then

covered with whins as well as grass. Thither, every morning at sunrise,

the town herd, with sound of horn, drove the cows of the inhabitants, and

there lie tended them all day till sundown—a very necessary duty when

hedgerows were unknown, and one that accounts for the number of

"herds" in olden days, who kept their charges from trespassing

on the growing crops. In the autumn, after harvest, when the sheaves had

been safely gathered into the stackyard, the herds had an off-time, for

then the stubble lands formed one vast grazing ground, where the cattle,

sheep, and swine, and even the geese, of which the Leithers kept large

flocks, wandered and grazed at will.

|