|

THE story of some of our

Scottish towns is comparatively easy to write because they have their

origin in modern times, and consequently the records of their history are

usually both full and complete. But Leith is not one of these towns. It is

a town of ancient origin, its beginnings taking us far back into the years

of past time, and its story, in the earlier years of its history, has to

be laboriously sought in many an old charter or other document.

From these documents we

learn that as far back as eight hundred years ago Leith was a thriving

village. Its houses nestled along the mouth of the Water of Leith, just

where the Shore now stands. Unfortunately, we know very little of this old

village, for it never entered into the thoughts of the monks—who were

the only chroniclers of those days—that future generations would be

interested in knowing something of the Leith of their days and the life of

its inhabitants. The information they give us is scanty in the extreme,

and thus it is exceedingly difficult to form a clear mental picture of

this Leith of other days.

Of one thing we may be sure: fishing would be the chief

occupation of the people of the village. And of one other thing we can be

equally certain, and that is that the date of the foundation of Leith,

could we but get it, would be found to be much further back than the

twelfth century. In our own days we read of cities springing up in a

single night, like Jonah’s gourd, but in those days towns and villages

developed very slowly. There was then no such thing among them as

"mushroom growth." They grew in size only by slow degrees; and

so, if Leith was an important place eight hundred years ago—important,

that is, according to the ideas of those times—its history must have

begun at a much earlier date. But there are no records of. Leith which go

back further than 1143, and there is no likelihood of any such ever being

discovered.

If Leith, then, dates so far back into olden times, you

may be tempted to ask why the Leith of to-day contains so very few really

old houses. The reasons are not far to seek. Leith’s history is not only

interesting but it is also eventful. Its history has often been of much

more than local note, and on more than one occasion the fortunes of Leith

have been the point on which the whole history of our country has turned.

This was especially so, as we shall see, in the days of Queen Mary. Now a

town cannot hope to bear the brunt in troublous times and escape

unscathed. Leith has often had to pay a heavy penalty for its share in

Scotland’s history. For example, when the Earl of Hertford led an

invading force into Scotland because the Scots had rejected the contract

of marriage between the English Prince Edward and the young Mary Queen of

Scots, Henry VIII. ordered him to burn Leith, and, if necessity required

it, to massacre its inhabitants. Hertford faithfully carried out the first

part of his instructions. Having possessed himself of Leith, he destroyed

the pier, and then proceeded to set fire to the town, reducing to ruins as

much of it as he possibly could. It is small wonder that Leith to-day

contains so few old houses.

Then, again, in modern times the magistrates of Leith

have carried through many improvement schemes, and this has meant the

sweeping away, not of single houses, but of whole streets. While we are

glad that light and air have been let into districts sorely in need of

them, yet we cannot but regret the disappearance of many of Leith’s

old-time houses. But though the houses themselves have passed out of

existence their sites can still be pointed out, and we still have pictures

of many of them. Some of these are shown in this book.

It has already been said that Leith existed as a

village more than eight hundred years ago. But there is a question to ask

which carries us very much further back in time than eight hundred years.

It takes us back to prehistoric times, times of which there is no written

history, because the rude, uncivilized people of those days could, of

course, neither read nor write. The question is this : When did man first

make his appearance in the district on which modern Leith now stands?

To this question nothing like a definite answer can be

given, but learned men who have made a special study of prehistoric

Scotland tell us that many thousand years must have elapsed since man

first appeared on the scene in our country. These archaeologists, as we

call them, are not agreed among themselves as to the age in which Scotland

became the scene of human habitation; and this is not to be wondered at,

as the evidence on this question must be got from unwritten and not

from written history, and naturally each archaeologist places his

own interpretation upon this evidence. But they all agree that it must

have been many thousands of years before the Christian era that man made

his appearance in our land.

By

using your imagination, try to picture how the area on which Leith stands

would look in those far-off and so very different times. Imagine the

disappearance of every building in Leith, of all its busy streets and

still busier docks, and then imagine the whole district covered with great

forests, the home of wild beasts such as the fox and the wild cat, and

other animals which have long been extinct in Scotland, as the wild boar,

the beaver, and the wolf. Imagine the sweep of the forests broken here and

there by a loch or marshy piece of ground, for there were innumerable

lakes, marshes, bogs, and morasses all over the low ground of our country

in those days. The Water of Leith would form part of the picture of your

mind’s eye, for, of course, then as now it journeyed on from its source

among the hills to where its waters mingled with those of the sea. But

gone would be the solid stone quays which now confine its course. Your

picture would show it turning and twining in its bed between its own

natural tree-clad banks, its clear-running water sparkling in the

sunshine. By

using your imagination, try to picture how the area on which Leith stands

would look in those far-off and so very different times. Imagine the

disappearance of every building in Leith, of all its busy streets and

still busier docks, and then imagine the whole district covered with great

forests, the home of wild beasts such as the fox and the wild cat, and

other animals which have long been extinct in Scotland, as the wild boar,

the beaver, and the wolf. Imagine the sweep of the forests broken here and

there by a loch or marshy piece of ground, for there were innumerable

lakes, marshes, bogs, and morasses all over the low ground of our country

in those days. The Water of Leith would form part of the picture of your

mind’s eye, for, of course, then as now it journeyed on from its source

among the hills to where its waters mingled with those of the sea. But

gone would be the solid stone quays which now confine its course. Your

picture would show it turning and twining in its bed between its own

natural tree-clad banks, its clear-running water sparkling in the

sunshine.

Although we cannot say with any degree of certainty

exactly when man first appeared on such a scene as you have just depicted

to yourself, we can be pretty certain that the district on which Leith

stands began to he populated before the land on which Edinburgh is built.

The ground on which Edinburgh now stands is higher than

that which lies between it and the sea, and would therefore afford more

security against the attacks of wild beasts and neighbouring tribes. But

to the uncivilized man of that time this advantage was more than

counterbalanced by other considerations. In the first place, the dense

forests would offer him little temptation to penetrate inland; and then,

also he would want to live as near as he could to the sea which provided

him with fish, and along the shores of which at ebb-tide he gathered the

limpets, mussels, and cockles which formed so large a part of his diet.

These first forefathers of ours lived in rudely

constructed dwellings, clothed themselves in skins, and lived on the

produce of the sea and such animals as they were able to kill in the

forests. They did not know the use of metals. Their implements and weapons

were made of stone, bone, horn, or wood. As time went on they gradually

became less barbaric. Their stone implements became more finely and more

symmetrically worked. Then a discovery was made which lifted the

prehistoric peoples into a higher stage of culture and civilization. This

discovery was the art of making bronze.

Lastly,

just as stone gave way to bronze, so bronze in its turn was superseded by

iron. When the use of iron was discovered, tools could be made which were

far superior to those made of bronze, just as bronze tools had been far

superior to those made of stone. As you doubtless already know, these

three periods in our history are known as the Stone, Bronze, and Iron

Ages. Lastly,

just as stone gave way to bronze, so bronze in its turn was superseded by

iron. When the use of iron was discovered, tools could be made which were

far superior to those made of bronze, just as bronze tools had been far

superior to those made of stone. As you doubtless already know, these

three periods in our history are known as the Stone, Bronze, and Iron

Ages.

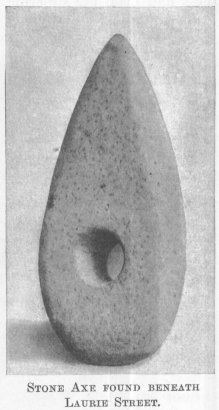

None of the dwellings of these old peoples are known to

have been discovered on the site on which Leith stands. This is not to be

wondered at, since they were made, not of stone, but of timber, which must

have decayed long ago. We cannot even find traces of their existence,

because these have been obliterated by the cultivation of the land before

a town came to be built on it. But the skulls of these early inhabitants

have been found, as also some of their wedge-shaped stone hammers and axes

of bronze.

You will find some of these in the Antiquarian Museum

in Queen Street, Edinburgh, a building which you ought to visit if you are

interested in prehistoric Scotland. In it you will see a very large

collection of articles belonging to prehistoric ages which have been

discovered at various times in different parts of Scotland. These have

been systematically arranged so that the visitor may trace the successive

changes in the life of prehistoric man and his gradual progress in

civilization. You will be especially interested in searching out the

objects which have been contributed from Leith.

To sum up the progress made from the first human

occupation of the site of Leith, we may say that at the beginning of the

Christian era prehistoric man had left much of his savagedom behind him.

He had begun to grow corn; he was in possession of domestic animals—the

horse, dog, ox, sheep, and goat; he had implements of iron, and he showed

considerable mechanical skill in various directions.

The materials of unwritten history are to be found in

caves, rock shelters, and underground dwellings, in river beds, in drained

lochs, in hill forts, and in the memorials erected to their dead by the

prehistoric races. With the coming of the Romans to Scotland in A.D.

80 we emerge from the period of unwritten history. Our knowledge of

the history of Leith will henceforward be obtained from books, and from

written records and documents.

For our knowledge of the Roman campaigns in Scotland we

have to depend largely, though not altogether, upon the materials of

unwritten history, and to gather their story from the remains the Romans

left behind them—their camps and their forts, and the objects lying

buried there beneath the surface. From these, and the story they reveal to

men skilled in their interpretation, we obtain much knowledge of the Roman

occupation of our district.

It was Julius Agricola who first led the Romans into

North Britain and brought them right into our neighbourhood. From the

south he made his way through the heart of the Cheviots, and, crossing the

river Tweed at Newstead, near Melrose, continued his march until he came

to the Lammermuir Hills. Along the line of his route he built forts at

strategic points like New-stead, and to overawe the natives he laid waste

the land as he advanced.

The news of the slow but steady advance of the

seemingly invincible enemy would reach the people of our district long

before the Romans themselves appeared. From vantage points on the Calton

Hill and Arthur Seat their scouts would be keenly watchful, ready to give

the alarm on the first appearance of the glittering spears and helmets of

the Roman legions. They would be in readiness to seek refuge within the

recesses of the deep forests, or to betake themselves to strongholds on

the lower hill-tops, like the fort on the rocky height overlooking

Dunsappie Loch, from which they could watch the movements of the invader

and find a safe retreat from his devastating legions.

Having crossed the Lammermuirs by the pass at Soutra,

Agricola had then to determine his further line of march. His aim was to

reach the central district of the Lowlands of Scotland—that is, the

country between the Firth of Forth and the Firth of Clyde. He had a choice

between two routes. From Soutra he could march almost due west. This would

be his most direct route but if he took it he would have to cross the

valleys of the North Esk and the South Esk, and the Pentland Hills would

also form another obstacle. On the other hand, an easy march of ten miles

from Soutra in a northwesterly direction would bring him to the shores of

the Firth of Forth at the mouth of the Esk, from which point his march

along the coast plain would present few difficulties.

He chose the latter route. Agricola, as Tacitus tells

us, was a skilled military engineer, and his quick eye at once perceived

the fine strategic position of Inveresk, protected as it was on west and

south by the great Caledonian Forest, and safe from attack on the east by

Pinkie Cleuch. It commanded all the routes from the south and east going

westwards towards the Clyde. Many remains of the great fort built by the

Romans at Inveresk are still to be seen, including the heating chambers of

their baths, while Inveresk Church and numerous other buildings near it

have probably been erected from stones taken from the fort.

Leaving a garrison behind him, and crossing the Esk by

a wooden bridge—the present so-called Roman Bridge not being built until

many centuries later—Agricola marched westward by way of Restalrig to

the country between the Forth and Clyde, his military way passing right

through our parish. Whether there was any hamlet or village of the Britons

where Leith now stands we have no means of knowing; but as our district is

the meeting place of routes by road from the south, east, and west, it

must have been a centre of traffic for the population in forest clearings

and along the shore of the Forth.

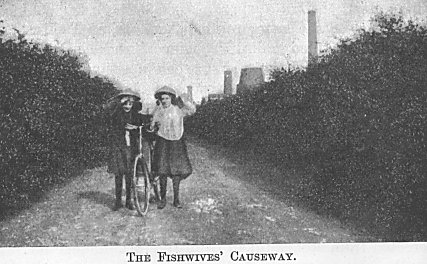

At the west end of Portobello there is a road of Roman

origin, known to-day as the Fishwives’ Causeway, though, of course, it

would not be so named in Roman times. This ancient road has for many long

years formed part of the boundary between the parishes of Duddingston and

South Leith. It is called a causeway because it was a causewayed road, as

all Roman roads were, its stones being mostly boulders from the seashore

close at hand, and quite undressed by the Roman work-men who laid them.

When the present Portobello Road was made about 1770, the fishwives of

Fisherrow, on their way to Edinburgh to dispose of their fish, continued

to favour the old causewayed road in preference to the new; hence the name

Fishwives’ Causeway. It is a causeway no longer, its stones having been

lifted and utilized in the construction of the great wall enclosing the

Craigentinny parks on the left side of the turnpike road from Wheatfield

to Portobello, where their round boulder shape at once betrays them.

In the year 180 the hated Romans were driven south of

the Cheviots. Yet Leith had not seen the last of the Roman legions, for in

the year 208 the great soldier emperor, Severus, set sail from York for

the Forth with a mighty fleet to punish the wild Caledonians for their

raids beyond Hadrian’s Wall. We can imagine the excitement and alarm

when the great armada was seen heading up the Forth. Severus landed his

troops at Cramond, which became his headquarters during his three years’

stay in Scotland; and there, as at Inveresk, you may see stones showing

Roman handiwork and an eagle that some Roman soldier with an artistic eye

has carved on the Eagle Rock by the shore. Severus was to find, as Edward

I. centuries later, that to win victories is not to conquer a country,

and, when he sailed from Cramond on his return to York, the Roman capital

of Britain, the shores of the Forth saw the Roman legions for the last

time.

The many chance finds of Roman relics that have been

made within the bounds of Edinburgh and Leith have led to the belief that

a Roman post midway between Inveresk and Cramond must have existed

somewhere in our neighbourhood. The discovery of Roman bricks from time to

time in the foundations of St. Margaret’s Chapel in Edinburgh Castle has

led some to think that a Roman station once existed there. Roman coins

have been found at several points, including the Fishwives Causeway and

Leith Walk, and a rich find of Samian ware—the best china of the Romans—was

uncovered in digging the foundations of the Regent Arch in the landward

part of our parish. Such discoveries do not necessarily indicate a Roman

settlement, for such chance finds occur in all parts of Scotland, and even

in countries the Romans never knew. They are rather a proof that during

the Roman occupation much commercial intercourse grew up between the

Britons and their conquerors, and that this trade continued long after the

Roman legions had retired beyond the wall of Hadrian.

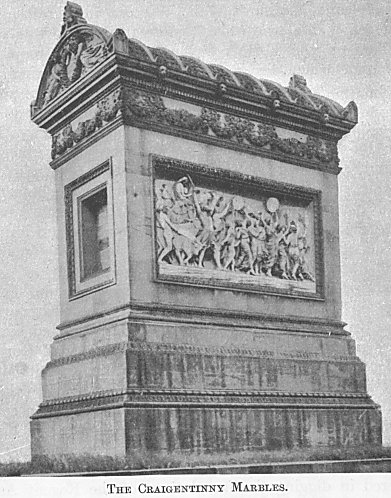

The Romans used to bury their dead in tombs ranged along the sides of

the roads outside their cities—the strip of ground on each side being

laid out much after the manner of our cemeteries. The famous Appian Way,

the great road that led southwards from ancient Rome, is flanked on both

sides for many miles with handsome tombs. Though Roman tombstones have

been discovered in other parts of Scotland, none has so far been found in

our neighbourhood. By a strange chance, however, one may see a great

sepulchral monument, designed from a tomb on the Appian Way, standing

solitary and alone in one of the Craigentinny parks close by the Fishwives’

Causeway, and just within the ancient parishes of South Leith and

Restalrig. This is the tomb of William Henry Miller of Craigentinny, who

wished to be buried in one of his own fields. It is ornamented with two

beautifully sculptured marble panels, known to fame as the "Craigentinny

Marbles." It is a strange coincidence indeed that full sixteen

centuries after the Romans left our district there should have been

erected directly on the Roman road a tomb so purely Roman in its design as

that which we have at Craigentinny.

|