|

You might like

to view the video "Mull of

Kintyre"

Preface

In the following pages I essay to guide my

readers to new ground, even to "the Land's End" of Scotland, —

for such is the English meaning of the Gaelic word Cantire,

Ceantire, "the Land's End," which is the southern part of

the county of Argyle, and is a peninsula only twelve miles

removed from Ireland, washed by the Atlantic, and flanked by the

Isles of Arran and the southern Hebrides. I venture to call

Cantire new ground, for in truth it is somewhat of a terra

incognita, and is but rarely visited, and has been but

barely mentioned by the guide-books, some of which indeed do not

bestow any description upon Cantire, evidently regarding it as a

"Western Highland district which no tourist would desire to

explore.

For, it is a country which must be visited

for its own sake; and the traveller, in quest of Highland

celebrities, need not, on his way to them, pass through Cantire.

It lies south and west of the better-known portions of the

Scottish Highlands; and although so many thousand tourists

annually visit those spots which fashion has very justly

pronounced to be so invitingly beautiful,—but which, rather more

than a century ago (as they were hard to be got at), were deemed

to be the types of all that was uninteresting and repulsive,—

yet not even a driblet of this annual stream is filtered through

Cantire. It lies out of the beaten track; it is somewhat of a

journey to get at it, to get through it, and to get away from

it; and, in these days of rapid locomotion, when the British

tourist can breakfast in Glasgow, and "do" Dumbarton, Loch

Lomond, Rob Roy's country, Loch Katrine, the Trossachs, and

Stirling, within the limits of one summer's day, and can sleep

in Edinburgh the same night, he can get more for his money and

for his after-conversation out of such a tour as this, than he

can do by going out of his way to see a district of the

Highlands, which must consume at the very least three or four

days of his time to get to and away from, and in which his home

friends will probably not take the slightest interest. For the

British tourist is a gregarious and sheep-like animal, and

Brown's instinct leads him along the beaten track, where he is

sure to meet with Smith, Jones, and Robinson, and where

railways, steamers, coaches, and well-appointed inns fit into

each other with ease and comfort.

And thus, although the Western Highlands have

been so much visited and described, the peninsula of Cantire has

well-nigh escaped notice. It is true that when compared with

certain other better-known districts, the scenery of the Land's

End of Scotland must (in some particulars) take an inferior

rank; but it only fails when put to the test of comparison; and

after all this test is but a variable one, dependent upon the

diversities of taste, and for all practical purposes next to

worthless. Brown's remark, that the Fall of Foyers is a hundred

times as. big, or ten times as stunning, as that tiny cascade in

the glen which honest Smith is admiring with all his artistic

heart and soul, is no real depreciation of the smaller fall. Nor

ought the satisfaction with which Robinson, prone in heather,

regards the Cantire panorama from his hill twelve hundred feet

above the Atlantic, to be in any way damped by the sneer of

travelled Jones: "Ah! you've never been up the Coollins!"

But whatever may be said of the general

scenery of Cantire, when compared with that of better-known

districts in the Western Highlands, yet it has its

distinguishing characteristic of a peninsula to mark it out as

sui generis; and as the peninsula, in its widest part, is

not more than ten or twelve miles, the sea is a main object

(this is mentioned as a fact and not as a pun) in all the

Cantire views. Stand where you will, unless buried deep in the

winding glens, and you have abundant sea-scape as well as

landscape. Traversing the centre of Cantire, and forming the

back-bone of the peninsida, is a range of hills and mountains,

averaging about twelve hundred feet in height, but including

greater altitudes, and crowned by Cantire's "monarch of

mountains," Beinn-an-Tuirc, "the Wild-Boar's mountain," whose

summit is 2170 feet above the sea. The view from nearly every

heathery moor is panoramic in its extent, and varied and

beautiful in its details. To the west is the great Atlantic, its

broad bosom studded with the Highland gems of the southern

Hebrides; to the east is Kilbrannan Sound and the Firth of

Clyde, with the torn peaks of the lovely isle of Arran. Further

north is Loch Fyne, the Isle of Bute, and a mass of mountains,

among which Ben Lomond is plainly to be discerned. Due north may

be seen Ben More and the mountains of misty Mull; and to

the southward lies, like a blue cloud upon the sea, that portion

of the northern coast of Ireland that extends from Fair Head to

the Giant's Causeway. Every way there is a sea-view, diversified

for the most part with islands; and when we combine this with

the varied inland scenery, we might almost apply the words of

Milton to this Highland ground of Cantire, and say:

"All is here that the -whole earth yields,

Variety -without end; sweet interchange Of hill and valley,

rivers, woods, and plains, Now land, now sea, and shores with

forest crown'd, Kocks, dens, and caves."

The "forest-crowned" shores are even found

here and there, though the greater part of the sea-board is

destitute of timber. The Mull of Cantire,—the veritable "Land's

End,"—is peculiarly bare, and is for the most part a wild region

of heath-covered hills, girdled by ragged rocks, against which

the waves of the Atlantic, after their three-thousand-mile race,

are dashed with a furious roar, that has been heard (so it is

stated) at a distance of forty miles. The highest mountain upon

the Mull is Cnoc Maigh, which attains an altitude of 2063 feet,

and which has apparently been named Cnoc Maigh, or "the Hill of

the Plain," on the lucus a non principle, as it rises

from a confused pile of mountains, some of which are but little

its inferiors in altitude, and from all of which the views are

varied and magnificent. To the wildness of the scenery in the

southern, portion of the peninsula, the soft beauty of the

northern affords a marked and agreeable contrast, and the

loveliness of West Loch Tarbert is like a confused memory of

Loch Katrine and Windermere.

But, whatever difference of opinion may exist

as to the scenery of Cantire, there can be but one opinion as to

its being a district which yields to no other in the Western

Highlands both in interest and importance. Cantire was the

original seat of the Scottish monarchy, and its chief town was

the capital of the Scottish kingdom centuries before Edinburgh

existed. It was the first part of Western Scotland where

Christianity took root; for in Cantire St. Columba's tutor, and

then St. Columba himself, preached the Gospel before it had been

heard at Iona, or in any other part of the Western Highlands and

Islands. From its nearness to Ireland it was subject to other

invasions than those by the Danes; and from its being one of the

chief territories of the Lords of the Isles, and having within

its boundaries some of their most important strongholds, its

soil was the scene of perpetual feuds and chronic wars. In the

following pages these points will be found to be treated, I

trust, with conciseness and clearness, but yet with sufficient

fulness.

My visit to Cantire was made during the

months of August and September, 1859; and since then I have been

at considerable pains to collect from reliable sources a large

body of information, statistical and archaeological, on every

point that would illustrate the history, antiquities, scenery,

and characteristics of this interesting Highland territory of

the Lords of the Isles, as well as the dress, manners, customs,

sports, and employments of the inhabitants, together with, their

moors and glens, their lochs and rivers, their towns, villages,

churches, castles, farms, and cottage dwellings. In short, so

far as in me lay, I have endeavoured to give a full and

informing sketch of the peninsula and people of Cantire. I have

also added a description of the route to and from Cantire by the

Firth of Clyde, the coast of Arran, Kilbrannan Sound, Loch Fyne,

and the Kyles of Bute; together with a brief account of Islay

and Jura, and those other islands of the Southern Hebrides that

lie off the western coast of Cantire.

My knowledge on many points must necessarily

have been but slight and superficial, and I therefore gratefully

pay testimony to the kindness of those Cantire friends who have

so readily assisted me with information. I have acknowledged my

obligations to them in various portions of my book; and I need

here but mention the names of the Eev. Duncan Macfarlane of

Killean, Keith Macalister, Esq., of Glenbarr Abbey, the Hon. A.

H. Macdonald Moreton, of Largie Castle, and William Hancocks,

Esq., of Glencreggan, without whose kindness and hospitality

this book would not have had an existence.

I would also wish to especially acknowledge

my obligations to Mr. Peter Mcintosh, of Campbelton, for the

greater part of those curious and characteristic tales and

legends with which my descriptions are relieved. During a long

and well-spent life Mr. Mcintosh has turned his attention to the

collection and preservation of the fast-dying records of past

customs and beliefs, and has been a pioneer in that movement

which Mr. Campbell has so well inaugurated in his

lately-published volumes of the "Popular Tales of the West

Highlands," to which I have frequently referred in the following

pages, although their mention of Cantire is confined to five

brief passages.

Greatly aided, therefore, by Mr. Mcintosh,

with slight help from other sources, both public and private, I

have been enabled to collect upwards of fifty popular tales

relating to Cantire: the titles of the principal stories will be

found (under the head of Story) in the Index which I have

prepared for the book, and which, without being overladen with

references, will I trust be found sufficiently compendious for

all useful purposes.

Cantire has hitherto been very imperfectly

and incorrectly mapped, and it is hoped that the map given in

the present work will be found to surpass its predecessors. If

the truth must be told, it has given me more trouble than all

the rest of the book. I compiled it from various sources, — my

own observation, private charts kindly placed at my disposal,

and the best published maps. The coast lines have been adopted

from those in the Admiralty charts,—(" Scotland, West-coast;

Sheets 2 and 3, — 1966, 2159 — surveyed by Captain Robinson;")

and the mountain ranges and other portions are chiefly based

upon Mr. Keith Johnston's large map of Southern Argyleshire,

which (the Ordnance Survey not having mapped Cantire) is said to

be the best map of the peninsula. There are many errors,

however, in Mr. Johnston's map, and considerable differences and

discrepancies will be found on comparing his' map with that in

the present work. This is notably the case with regard to the

names of places, and in this respect I. encountered considerable

difficulties. Scarcely any two maps agreed upon this point, and

when I went to original authorities, and to people upon the

spot, the Gaelic name has been spelt for me by my Celtic

informants in so many different ways, (owing chiefly to the

variations in dialect) that after all, I have had to choose

between several varieties, and to select that name which seemed

to me to have the best title for correctness. In this dilemma, I

have generally been guided by the author of the " Statistical

Account" of each parish, who, from his local knowledge and

acquirements, could speak on this point ex cathedra. I

also received the valuable assistance of Mr. Edward Weller, F.

E. G. S., under whose careful superintendence the map has been

engraved.

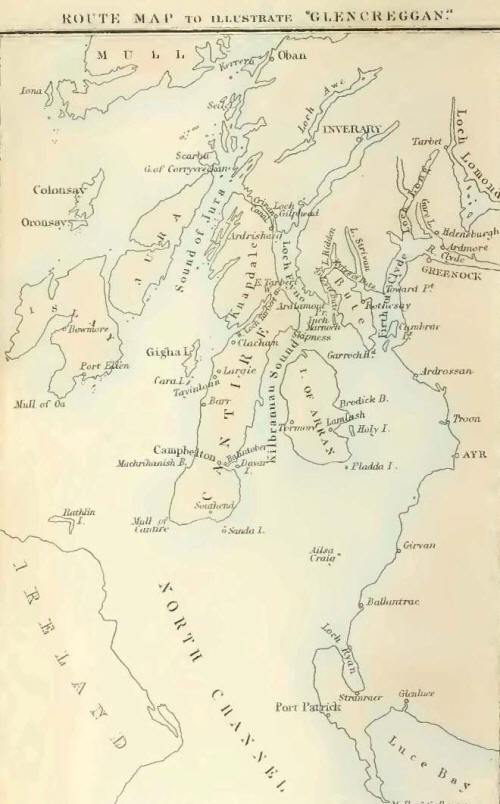

A Route Map, and a Geological Map, have also

been added. For the latter I am indebted to the kindness of an

eminent geologist, whose name (were I allowed to mention it)

would be a sufficient guarantee for its correctness. That it

greatly differs from Macculloch's map is attributable partly to

the older map being limited to "the general features" of the

Cantire geology, and partly to the science having been somewhat

revolutionised since Macculloch's day.

With regard to the Illustrations, those in

colours have been copied in chromo-lithography from my large

water-colour drawings, a task which has been performed by the

Messrs. Hanhart, with great skill and fidelity, to my own

satisfaction, and I trust, to the gratification of my readers,

who will be enabled to judge from them, better than from any

verbal description, how wild and picturesque is the scenery of

Cantire. The woodcut illustrations (engraved by Mr. Branston)

are from my own sketches, assisted, in a few instances, by

photographs specially taken for this work. The greater part of

the landscape illustrations have been drawn upon the wood by Mr.

J. Willis Brooks, and are denoted in the Lists of Illustrations

prefixed to the volumes. For all the other woodcuts I myself am

answerable.

My thanks are due to the publishers, who have

not spared pains or expense on the production of this work; and

I trust that by their aid my sketches and descriptions may tempt

some of the numerous Highland tourists, who have never had an

opportunity of seeing the originals, to take as pleasant a tour

as I myself enjoyed in the land of the Lords of the Isles—Cantire

— the "Land's-End " of Scotland,

June, 1861.

CONTENTS

THE FIRST VOLUME

Chapter I - The Scenery of the Clyde

Chapter II - Off the Coast of Arran

Chapter III. - In Kilbrannan Sound

Chapter IV - On Highland Ground

Chapter. V - The Land's End of

Scotland

Chapter VI - Dunaverty and its

Traditions

Chapter VII - The Old Scottish Capital

Chapter VIII - The Chief Town of the

Lords of the Isles

Chapter IX - Kilkerran and the First Missionary in the Highlands

Chapter X - Saints and Legends

Chapter XI - A Very Amusing Road

Chapter XII - Glenbarr

Chapter XIII - Glencreggan

Chapter XIV - Half a Dozen of the Hebrides

Chapter XV - Shade and Shine

Chapter XVI - Highlanders and Highland Dress

Chapter XVII - Heather-Land THE SECOND VOLUME

Chapter XVIII - Cantire's monarch of

mountains, and its legends

Chapter XIX - On the Moors

Chapter XX - Grouse-Land

Chapter XXI - Still-Life, and Highland Dainties

Chapter XXII - Cantire Bucolics Past

and Present

Chapter XXIII - Highland Farm-Houses

Chapter XXIV - Highland Cottages

Chapter XXV - On the Atlantic Shore

Chapter XXVI - Common Objects on and off the Sea-Shore

Chapter XXVII - Muasdale, A

Watering-Place - In Cloudland

Chapter XXVIII - Killean - A Scotch

Kirk and Sabath

Chapter XXIX - Largie

Chapter XXX - A Canter through Cantire

Chapter XXXI - East Tarbert and Loch

Fyne Herrings

Chapter. XXXII - The Kyles of Bute

APPENDIX

The Cantire Life-Boat

Dermid:

A Poem

The MacDonalds

You might also want to read his

other book...

Argyll's Highlands

Or MacCailein Mor and the Lords of Lorne, with tradionary tales

and legends of the County of Argyll and the Campbells and

MacDonalds by Cuthbert Bede and edited by John MacKay (1902)

(pdf) |