|

THOMSON, REV. JOHN.—The title

of the Scottish Claude Lorrain which this reverend candidate for distinction

acquired, at once announces the walk in which he excelled, and the progress

he attained in it. He was born in Dailly, Ayrshire, on the 1st of

September, 1778, and was the fourth and youngest son of the Rev. Thomas

Thomson, minister of the parish of Dailly. As he was destined by his father

at an early age for the minsitery, John’s studies in boyhood were directed

with a reference to this sacred calling; but already, he had unconsciously

made a choice for himself and such a choice as was little in coincidence

with the wonted occupations of a country pastor. Instead of submitting to

the drudgery of the school-room and the study, the young boy was to be found

afield, roaming in quest of the beautiful and the picturesque, for which the

banks of the water of Girvan are so justly famed; and to extend these

explorations, he frequently rose at two o’clock in a summer morning, and

made a journey of miles, that he might watch the effect of sunrise, as it

fell upon different portions of the scenery, or played among the foliage

with which the cliffs and hill tops were clothed. What he thus appreciated

and admired, he was anxious to delineate, and this he did on pasteboard,

paper, or the walls of the house, while his only materials for painting were

the ends of burnt sticks, or the snuffings of candles. This was by no means

the most hopeful of preparations for the ministry, and so he was told by his

father, while he was informed at the same time, that the pulpit was to be

his final destination. John at first stood aghast, and then wept at the

intelligence. He was already a painter with all his heart and soul, and how

then could he be a minister? He even knelt to the old man, and besought him

with tears in his eyes to let him follow out his own favourite bent; but the

father in reply only patted the boy’s head, bidding him be a good scholar,

and go to his Latin lessons. In this way, like many Scottish youths of the

period, John Thomson, through mistaken. parental zeal, was thrust forward

towards that most sacred of offices for which, at the time at least, he felt

no inclination.

As nothing remained for him

but submission, the embryo painter yielded to necessity, and in due time was

sent to the university of Edinburgh. There, besides the learned languages,

he earnestly devoted his attention to the physical sciences, and became a

respectable proficient in astronomy, geology, optics, and chemistry. While

in Edinburgh, he lodged with his brother, Thomas Thomson, afterwards the

distinguished antiquarian, who was twelve years his senior, and at that time

a candidate for the honours of the bar; and in consequence of this

connection, John was frequently brought into the company of Walter Scott,

Francis Jeffrey, and other rising luminaries of the literary world, who had

commenced their public life as Scottish barristers. It was impossible for

the young student to mingle in such society without catching its

intellectual inspiration; and he showed its effect by the proficiency he

made in the different departments of his university curriculum, as well as

the acquisition of general knowledge, and his facility in imparting it. Such

was his career during the winter months; but when the return of summer

released him from attendance on his classes, he showed his prevailing bent

by an escape into the country, where the green earth and the blue sky were

the volumes on which he delighted to pore. During the last session of his

stay at college, he also attended for a month the lessons in drawing of

Alexander Nasmyth, the teacher of so many of our Scottish artists, by whose

instructions as well as his own diligent application, he improved himself in

the mechanical departments of pictorial art.

Having finished the usual

course of theology, John Thomson, at the age of twenty-one, was licensed as

a preacher; and his father having died a few months after, he succeeded him

as minister of Dailly in 1800. A short time after his settlement as a

country clergyman, he married Miss Ramsay, daughter of the Rev. John Ramsay,

minister of Kirkmichael, Ayrshire. He had now full inclination (and he took

full leisure also) to pursue his favourite bent, and thus, the pencil was as

often in his hand as the pen, while the landscapes which he painted and

distributed among his friends, diffused his reputation as an artist over the

country. But little did the good folks of Dailly rejoice in his growing

fame: in their eyes, a minister who painted pictures, was as heinous a

defaulter as the divine who actually played "upon the sinfu’ sma’ fiddle;"

and this, with his buoyant fancy and exuberant spirits, which were sometimes

supposed to tread too closely upon the bounds that separate clergymen from

ordinary mortals, made the rustics suspect that their pastor was not

strictly orthodox. This dislike of his strange pictorial pursuits, which

they could not well comprehend, and his mirthful humour, which they could

comprehend too well—for Mr. Thomson, at this time, could draw caricatures as

well as landscapes— excited the attention of his brethren of the presbytery,

one of the eldest of whom (so goes the story) was sent to remonstrate with

him on the subject. The culprit listened in silence, and with downcast eyes;

and, at the end of the admonition, was found to have sketched, or rather

etched, an amusing likeness of his rebuker with the point of a pin upon his

thumb-nail.

The incumbency of Mr. Thomson

in Dailly was a short one, as in 1805 he was translated to the parish of

Duddingston, a picturesque village within a mile of Edinburgh, and having

the manse situated on the edge of its lake. In the neighbourhood of the

northern metropolis, now rising into high literary celebrity, surrounded

with scenery which can scarcely anywhere be surpassed, and by a society that

could well appreciate his artistic excellence, he gave full scope to his

hitherto half-imprisoned predilections, while his improvement continued to

keep pace with the number of his productions. He was soon noted as a

landscape painter of the first order; and such was the multitude of

commissions that poured upon him, that sometimes nine carriages could be

counted at the manse door, while at one period his revenue from this

profitable source did not fall short of £1800 per annum. Who can here fail

to regret the over-eager zeal of his father, by which such a painter was

compelled to adopt the ministerial office; or be slow to perceive, that

these were not the kind of applications that should beset a clergyman’s

dwelling? True, the pulpit of Duddingston was regularly occupied on the

Sabbath, and the usual number of sermons preached; but Edinburgh was close

at hand, and abounded with probationers whose offices could be secured at a

day’s notice. In the meantime, as years went onward, Mr. Thomson’s love of

rich and striking scenery continued unabated, and his long pilgrimages in

quest of it as ardent and frequent as ever. Often, indeed, he was to be

found travelling with Grecian Williams, long before dawn, towards some

selected spot, where they wished to delineate its appearance at the first

sunrise; and having reached it, the enthusiastic pair would sketch and

retouch, until each had depicted the view according to his own perceptions

and tastes, communicating from time to time the progress they were making,

and playing the part of friendly critics on each other’s productions. On

returning to his home from these excursions, it was commonly a change from

the beauties of nature to the charms of conversation and social intercourse;

for the manse of Duddingston was famed for hospitality, while the artistic

reputation of its tenant was so high and so widely spread abroad, that few

strangers of distinction in the fine arts arrived in Edinburgh without

visiting Mr. Thomson. Independently, too, of his conversational talents, and

warm-hearted affectionate disposition, that endeared him to his guests, and

made his society universally courted, Mr. Thomson was almost as enthusiastic

a lover of music as of painting, and played both on the violin and flute

with admirable skill. Nor were the more intellectual studies of his earlier

days neglected amidst the full enjoyment of society, and his increasing

popularity as an artist, and several articles on the departments of physical

science which he wrote in the "Edinburgh Review," were conspicuous even in

that distinguished journal for the vigour of their style and clearness of

their arguments.

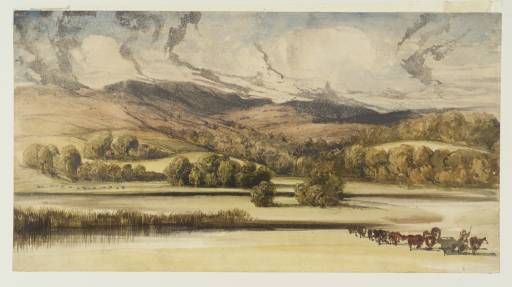

A View in Scotland

Such a course of

uninterrupted felicity would at last have become cloying; for man, as long

as he is man and not angel, must weep and suffer as well as laugh and

rejoice, in order to be as happy as his mixed and imperfect nature will

permit. This the minister of Duddingston undoubtedly knew, and besides

knowing, he was fated to experience it. For in the midst of his success, and

when his young family was most dependent upon maternal care, he became a

widower. The evil, heavy as it was, was not irremediable, and in fitting

time a comforter was sent to him, and sent in such romantic fashion as to

enhance the value of the consolation. An amiable and attractive lady,

daughter of Mr. Spence, the distinguished London dentist, and widow of Mr.

Dalrymple of Cleland, happened one day, when visiting Edinburgh, to step

into a picture-shop, where she saw a painting of the Fall of Foyers. Struck

with the originality and beauty of this production, she eagerly asked the

name of the artist, and was astonished to find that it was Mr. Thomson of

Duddingston; for, although she had seen several of his former paintings,

none of them was to be compared to this. She was anxious to be personally

acquainted with the author of such a painting— and such an anxiety seldom

remains ungratified. She was soon introduced to him by mutual friends, and

the first time that Thomson saw her, he said to himself, "That woman must be

my wife; never have I beheld for years a woman with whom I could sympathize

so deeply." The result may be easily guessed. In a short time, she became

Mrs. Thomson; and seldom, in the romance of marriage, has a couple so well

assorted been brought together, or that so effectually promoted the

happiness of each other. Independently of her taste in painting, she was,

like himself, an ardent lover of music; and such was her earnest desire to

promote the cultivation of the latter art, that she set up a musical class

at the manse, which was attended not only by the most tasteful of the young

parishioners of Duddingston, but by several pupils from Edinburgh, all of

whom she instructed of course gratuitously. Two minds so assimilated could

not fail to be happy, unless there had been a dogged determination to be

otherwise, which was not in their nature, and, accordingly, the domestic

ingle of Duddingston manse beamed brighter than ever. As if all this, too,

had not been enough, an event occurred by which every chivalrous feeling in

the heart of Mr. Thomson was gratified to the full. His eldest son was first

mate of the "Kent" East Indiaman, that took fire and went down at sea—an

event that was associated with such circumstances of heroic devotedness,

that it is still fresh in the memory of the present generation. At this

trying crisis, when the captain was stunned with the magnitude of the

danger, and unable to issue the necessary orders, young Thomson assumed the

command, and used it with such judiciousness, promptitude, and presence of

mind, that the whole ship’s crew and passengers were extricated from the

conflagration, and conveyed to the shore in safety, while he was himself the

last to leave the vessel.

The paintings of Mr. Thomson

were so numerous, that it would be difficult to attempt a list of them, more

especially as they were exclusively devoted to portions of Scottish scenery

over the whole extent of the country. As the manse of Duddingston commanded

a full view of the castle of Craigmillar, and the picturesque landscape that

surrounds it, he made this stately ruin and its accompaniments the subject

of many a painting from different points of view, and under every variety of

light—from the full blaze of an autumnal noon day, to the soft half-shadowy

outline and tint of a midnight moon. The striking towers and fortalices

along the Scottish coast—famed as the ancient residences of the champions of

our national independence, from Dunstaffnage, Dunluce, and Wolfs-Crag, down

to the humble peel upon the rocky sea-shore—were also the subjects of his

pencil; and when these were exhausted, he devoted himself to the romantic

inland scenery, which the genius of Scott had but lately opened, not only to

the world, but his own countrymen—the Trosachs, Loch Achray, and Achray

Water, as well as the more familiar scenes of Benblaffen, Glenfishie, Loch

Lomond, Loch Etive, and others, in which land and water, striking outline,

change of light and shade, and rich diversity of hue, are so dear to the

painter of nature, as well as the general tourist. As Mr. Thomson was not a

professional artist, in the proper acceptation of the term, he was not

eligible for the honour of membership among the royal Academicians; but his

paintings, nevertheless, were gladly received into their Annual Exhibitions;

while his merits, instead of being regarded with jealousy, were acknowledged

as occupying the front rank among the British masters of landscape-painting,

and incontestibly the best which his own country had as yet produced.

These indefatigable labours

were continued till 1840, when symptoms of rapid constitutional decay began

to manifest themselves, so that he was laid aside altogether from clerical

duty; and when autumn arrived, he occupied a sickbed, without any prospect

of recovery. His death was characteristic of that deep admiration and love

of the beauty of nature which had distinguished him through life, and

secured him a high name in the annals of his countrymen. On the 26th of

October, feeling that his last hour was drawing nigh, he caused his bed to

be wheeled towards the window, that he might look upon the sunset of a

bright afternoon; and upon this beloved spectacle he continued to gaze until

he swooned from exhaustion. This was his last effort, and he died at seven

o’clock on the following morning.

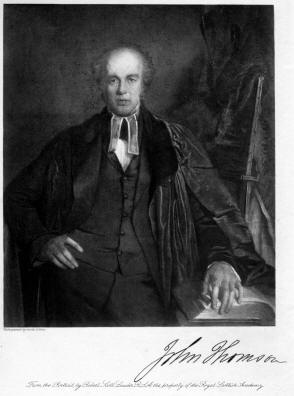

Preface to the

Second Edition

NEARLY

twelve years have elapsed since this Memoir of

the Rev. John Thomson of Duddingston was first published. Received as it

then was with flattering appreciation by press and public alike, it was

speedily taken up, and for several years the book has been out of print.

It has frequently of late been

suggested to the author that in view of the greatly increased interest now

shown in Art and artists, the time had come when a new and popular edition

of the life and work of one of the most celebrated of Scottish landscapists

might be received with as much favour as the first. Yielding to these

representations, this edition now offered to the public has undergone a

careful revision, while additional matter not formerly available has been

incorporated with the text. In this connection mention may particularly be

made of extracts from the private correspondence of Sir Thomas Dick

Lauder—author of Tales of the Scottish Highlands, The Great Floods of

1829 in Morayshire, The Wolf of Badenoch, etc. etc.—giving details of a

sketching holiday tour with Thomson in the north of Scotland in the summer

of 1831, which had been kindly placed at the author’s disposal, before her

death, by his daughter, the late Miss C. Dick Lauder.

The original illustrations are, with

one or two unimportant exceptions, here reproduced, and nothing has been

lacking in the effort to portray an attractive personality, sufficient, it

is hoped, to enable the reader to apprehend with some distinctness the

versatility and power of Thomson’s genius, the place he occupied as a

pioneer in the Scottish School of Landscape Art, and his share in the

founding of the Royal Scottish Academy.

W.B.

POETOBELLO, 1st May 1907.

Preface to the First

Edition

No adequate attempt has hitherto been made to give to the

public a life of this notable Scottish artist, or to bring together under

review the character of the work which has made him famous. This may

possibly have arisen from the fact that so many of his contemporaries and

most intimate friends—Sir Walter Scott, Lord Jeffrey, Lord Cockburn,

Professor Wilson, and others—bulk so largely in the literary annals of the

first half of the century as to have in some measure eclipsed the fame of

the artist minister of Duddingston.

The rise of the Scottish School of Landscape Art is both

an instructive and interesting story, and with the events of that story the

life of the Rev. John Thomson is so closely bound up that we feel justified

in claiming for him more recognition than he has as yet received.

Scotland at the beginning of the century was certainly

not distinguished for artistic culture, and landscape art especially was far

below mediocrity. With the finest scenery in the world, there was no one to

interpret its form and features, its hidden mysteries of colour and shade.

There were undoubtedly a few painters of portraits, some

of them distinguished enough in their own walk; but the painters of

portraits were too busy to have time to look at trees and rivers and lakes

and rocks and mountains. Patrons of Art were content to give commissions for

pictures of themselves and their wives to hand down as family heirlooms to

their children, but never dreamt of asking for a picture of a place. It is

possible there may have been love of locality all the same, and a certain

pleasure was doubtless taken in the beauties of the field, the garden, the

park with its trees, or even in the more rugged wildness of moor and

mountain; but what we call the love of Nature—looking at Nature through a

sympathetic per. ception of its innate beauty and soul-satisfying power—was

practically—at least so far as one can judge from outward manifestations—

non-existent.

True Art is the discovery of Nature. Like a coy maiden,

she must be courted to be won. The deep searching perception of the critic

is not sufficient for this. He may talk learnedly of what he thinks

defective in an artist’s work, but ask him to give his impressions of

scenery in the concrete, and in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred he will

honestly tell you he cannot; that he has neither the faculty of seeing in

Nature what is artistic, nor of interpreting her moods and humours for

others. ‘I don’t see these colours of yours in the sunset,’ said a lady once

to Turner. ‘I daresay not, madam,’ said the artist, ‘but don’t you wish you

could?’ This true artistic faculty, the very essence of Art, which grasps as

with unerring instinct the secrets of Nature not always on the surface, is

doubtless in some cases inborn, but more frequently it is the result of

years of patient study and observation. He who so evolves Nature’s

mysteries, that they appear as in a mirror, charming the sense and feeding

the imagination, is an artist indeed. We are immersed in beauty—the very

air is full of it—the vault of heaven above and the

fields around all speak of light and colour and grace of form, but only the

eyes of the few are open to the clear vision which can detach objects from

one another, and so group them as to satisfy the sense of beauty which, if

not common to all, it is possible to develop in even the most uncultured.

Tom Purdie, Scott’s gamekeeper and

factotum., was many years in his service, and being constantly in

the company of his betters, had picked up insensibly some of the taste and

feeling of a higher order. ‘When I came here first,’ said Tom to the

factor’s wife, ‘I was little -better than a beast, and knew nae mair than a

cow what was pretty and what was ugly. I was cuif

enough to think that the bonniest thing in a countryside was a corn-field

enclosed in four stane dykes; but now I ken the difference. Look this way,

Mrs. Laidlaw, and I‘ll show you what the gentle folks likes. See ye there

now the sun glintin’ on Meirose Abbey? It ‘s no’ a’ bright, nor it

's no’ a’ shadows neither, but just a bit screed

o’ light, an’ a bit daud o’ dark yonder like, and

that ‘s what they ca’ picturesque; and, indeed, it maun be confessed,’ said

honest Tom, ‘it is unco bonnie to look at. Thus it may happen that the

individual in whom simple tastes, combined with susceptibility to the best

and noblest of human influences, may prove himself, in spite of the

accidents of birth and the want of early training, one of the best of Art

critics. But Tom Purdie’s experience only went the length of admiration. The

power to discriminate between the useful and the beautiful, between the

purely utilitarian and what is aesthetically educational and soul. stirring,

and so to apply it either through the medium of the pen or the pencil, is

reserved to the artist; and he only is a great artist who follows after the

beautiful in Nature in a loving, reverential spirit, with earnestness of

purpose and increasing ardour following where she leads, and pointing out

her secrets so that others are forced tc follow and to admire.

What Sir Walter Scott by his living voice did for Tom

Purdie, he also did for his countrymen and the world by his pen; and what he

did with the pen, with no less truth, it may be said, his friend John

Thomson of Duddingston accomplished by means of his pencil and his brush.

Both were artists. Their materials or mediums were different. The one

was a word painter, the other gave himself

‘To paint the finest features of the mind,

And to most subtle and mysterious things

Give colour, strength, and motion.’

If the poetry of the one was a painting that can speak,

the painting of his friend was, we may say, a dumb poetry—speaking

in silent whispers—the adaptation of poetry to the

eye.

Thomson, like Scott and Burns, had the fine, far-seeing

sense of the painter-poet. His Art was not imitation merely. He was too

thoughtful for that. It partakes far more of the creative, and so reveals to

us Nature’s harmonies in skilful combination. Ralph Emerson, in his Essay on

Art, has said: ‘In landscape the painter should give the suggestion of a

fairer creation than we know. The details, the prose of Nature he should

omit, and give us only the spirit and splendour. He should know that the

landscape has beauty for his eye, because it expresses a thought which is to

him good; and this because the same power which sees through his eyes is

seen in that spectacle; and he will come to value the expression of Nature

and not Nature itself, and so exalt in his copy the features that please

him. Thus, the Genius of the Hour sets his ineffaceable seal on his work,

and gives it an inexpressible charm for the imagination.’

In the following pages we have endeavoured—imperfectly it

may be—to trace the development of Thomson’s art genius, and the influence

of his mind and work over the thought and Art of his

day and ours. We should have liked had we been able to give more details of

his life; but after half a century such details are difficult to get. Few of

his letters have survived the ravages of time. He has left us

no journal or diary; and even his sermons have all but disappeared.

This paucity of written material at our disposal has in some measure been

counterbalanced by a careful gleaning of contemporary literature, the

personal reminiscences and letters of relatives and old parishioners, and

Church Records of Presbytery and Parish.

In the circumstances anything like a connected narrative

of events in consecutive order was a task surrounded with peculiar

difficulties. It; therefore, a want of cohesion should here and there occur

to interrupt the current of the story, our readers will we hope sympathise

with rather than blame us in our endeavour so far to make bricks without

straw.

Where so many have been willing to help, it may seem

invidious to make a selection; but even at the risk of possible omission of

some whose kindness ought to be acknowledged, we must specially express to

the following noblemen and gentlemen our sense of our obligations and

sincere thanks :—His Grace the Duke of Buccleuch, the Right Hon. the Earl of

Rosebery, the Right Hon. the Earl of Wemyss and March, the Right Hon. the

Earl of Stair, the Right Hon. J. H. A. Macdonald (the Lord

Justice-Clerk), the Right Hon. Lord Young, Sir Charles Dairymple, Bart., M.P.,

H. T. N. Ogilvy, Esq. of Biel, R. S. Wardlaw Ramsay, Esq. of Whitehill,

Lockhart Thomson, Esq., Derreen, Murrayfield. Examples taken from their

collections will be found among our illustrations. They have been selected

from canvases large and small rather as typical specimens, than from

Thomson’s finest or most notable pictures. As a rule, we have avoided

reproducing pictures which have already been engraved or etched, and so

may be known to the public, preferring to illustrate

his work from pictures not generally known.

To the Secretaries of the National Galleries of London

and Edinburgh, and of the Royal Scottish Academy, we are indebted for much

valuable information; while we cannot sufficiently

recognise the invariable courtesy and kind assistance extended to us by

Mr. Hugh A. Webster of the University Library, Mr. Hew

Morrison of the Public Library, the Officials of Advocates’ Library,

Edinburgh, and Dr. Thomas Dickson of the Register House. Our dear friend,

the late Nr. J. M. Gray of the National Portrait Gallery, whose interest in

the work was sincere, and whose aid was invaluable, is, alas, beyond our

thanks. His untimely death has caused a blank in our Scottish Art literature

which may not easily be filled.

Among others whose names must not be overlooked are the

Rev. J. Hunter Paton of Duddingston and the Rev. George Turnbull of Daily,

both of whom have willingly contributed such local information as was within

their knowledge; while of the Rev. John Thomson’s relatives now living, we

gratefully tender our thanks to Lockhart Thomson, Esq. (a nephew), Mrs.

Isabella Lauder Thomson (a grand-daughter), Mrs. Captain John Thomson

(daughter-in-law), Mrs. Neale, Leicester (a grand-daughter), and Mr. H. H.

Pillans of the Royal Bank, Hunter Square, Edinburgh.

Last of all, we would specially mention our obligations

to the Hon. Hew H. Dalrymple, F.S.A. Scot., of Lochinch, whose assistance in

bringing to our knowledge and procuring access to Thomson’s works in the

private collections of our nobility has been cordially given, and is now

gratefully acknowledged.

PORTOBELLO, 1st December

1894.

Contents

Chapter I

Introduction—Birth and Parentage—Early Training—The

Parish School—The Minister’s Family—The Manse of Dailly—Early Aspirations

for Art— First Efforts—Thomas Thomson and Lord Hailes.

Chapter II

Edinburgh University—Lodgings in Hamilton’s Entry—New

Hailes and Lady Hailes—Companions—Sunday Morning Breakfasts—Scott, Jeffrey,

Clerk, Erskine — ‘The Exigencies of the State’

— Alexander Nasmyth— Lessons in

Painting—Completion of Divinity Course—Licence by Presbytery of Ayr—Ordination

at Daily—Marriage——Rev. John Ramsay of Kirkmichael—Reminiscences—Olose of

Ministry at Dailly—Presentation to Duddingston

Chapter III

Duddingston Church and Parish—Thomson’s Induction—The

Manse—Artistic Fervour—Ordination of Walter Scott to the Eldership—Scott a

Presbyterian—Member of General Assembly—Baptism of Scott’s Youngest Child by

Thomson—Scott’s Views on Episcopacy versus Presbyterianism—

Lockhart’s Life of Scott—Death of Mrs. Thomson—’ Grecian’ Williams—

Sir Francis Grant—Sir David Wilkie—J. M. W. Turner—Duddingston Loch in

Winter—The Duddingston Curling Club—Principal Baird

Chapter IV

Marriage with Mrs. Dairymple of Fordel—The Manse

Visitors—Provincial Antiquities of Scotland—Turner and Scott—Rossetti—William

Bell Scott—RuskIn—Anecdotes-Visits to London—Voyage with Dr. Thomas Chalmers

— Characteristics — The

Duke of Buocleuch’s order — Public Exhibitions in

Edinburgh—Thomson’s Influence—The Scottish School— Horatio Macculloch—Robert

Scott Lauder—Marriage of Isabella Thomson.

Chapter V

A busy Life—Parish Gossip-—Anecdotes—-The Lame Minister—’A bonnie wee bit of sky‘—The ‘Edinburgh’ Retreat—Pulpit Ministrations—Louis Cauvin’s Device—Thomson on ‘Moderation ‘—Doctrine and Practice— Portobello

Church—Moderates and Evangelicals—Mrs. Thomson’s Music Lessons—Stories of

John Richardson the Beadle.

Chapter VI

Sketching Excursions—Inverness, Moray, Arran, Kintyre,

Skye—The Blair-Adam or ‘Macduff’ Club—Its Origin—Annual Outings—Scott’s

Journal —Loch Leven, etc.—’ John Thomson’s delightful flute’—Falkland

Palace— Culross—A Sunday at Lochore—’ Let off’—’ No Sermon

‘—Reminiscences—Cassillis House—The ‘Hereditary Gardener’ of the Earl of

Monteith— Thomson at Abbotsford—The Bannatyne Club—Thomas Thomson and the

Acts of the Scottish Parliament—Club Suppers—Characteristics— Lord

Cockburn’s Opinion of Thomas Thomson—Death of Sir Walter Scott—Visit to Sir

David Brewster—Badenoch.

Chapter VII

Declining Health—Death—-Funeral—-Rev. John Thomson’s

Family—Dr. Thomas Thomson of Leamington—Captain John Thomson—Loss of the

Kent—Personal Character and Disposition.

Chapter VIII

Thomson’s Influence on Scottish Art— Review—Popular

Indifference—Dr. John Macculloch on Scenery—Pennant and Johnson—Scott as a

Word Painter—Thomson as an Artist—The Edinburgh Artists—First Edinburgh

Exhibition—The Royal Institution: its History, Exhibitions, and Lord

Cockburn on its Defects—The Scottish Academy.

Chapter IX

Thomson an Honorary Member of the Academy— His Style of

Art—The Provincial Antiquities of Scotland—Turner and Thomson

compared—Their Genius—Thomson and the Old Masters—A Student of Nature—Lord

Eldin’s Advice — Thomson’s Methods and Practice

— Death of Mrs. Thomson—Sale of Thomson’s Works,

1846—Public Opinion—The Scotsman and

Blackwood’s Magazine —

Thomson a Pioneer, Thinker, and Delineator—A Master of Landscape Art.

Appendix

Pedigree of the Rev. John Thomson

Portraits of the Rev. John Thomson |