IN the early exhibitions of the

Scottish Academy Thomson’s efforts in landscape held the foremost place,

and his claims to recognition as a master were so palpable that,

notwithstanding his being a member of another profession, these could not

possibly be overlooked, and he was accordingly elected in 1830 an Honorary

Member.

Many brilliant painters have

followed him since that time, but it will be frankly admitted that John

Thomson of Duddingston holds his own as one of the greatest in the

Scottish School. His Art is in many respects thoroughly original, and is

distinguished by a masterly, dignified style of composition which has

seldom been surpassed. It is a style founded in the first instance upon

the practice of the Dutch masters, afterwards drawing its influence from

Poussin, Claude, and the Italian School, but ultimately the outcome of a

close observation of Nature.

At

their best, his works show skilful selection of subject, powerful,

accurate drawing of details, and a happy combination in their composition

and arrangement of those qualities which give to the spectator the sense

of dignity, grandeur, repose, and harmony. These with the qualities of

abstract colour and tone, at once rich and deep, tempered by an

all-pervading sense of chiaroscuro, give to his portrayal of the scenery

of Scotland a charm and a glory that have not often been equalled by any

other native artist.

At

their best, his works show skilful selection of subject, powerful,

accurate drawing of details, and a happy combination in their composition

and arrangement of those qualities which give to the spectator the sense

of dignity, grandeur, repose, and harmony. These with the qualities of

abstract colour and tone, at once rich and deep, tempered by an

all-pervading sense of chiaroscuro, give to his portrayal of the scenery

of Scotland a charm and a glory that have not often been equalled by any

other native artist.

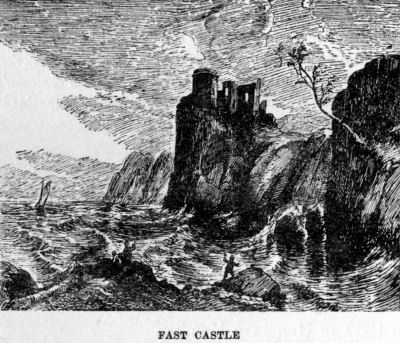

Whether it be a quiet, pastoral

scene, such as may be found in his pictures of the Lothians round his own

much-loved Duddingston Loch, or the wild, rocky scenery of Tantallon, Fast

Castle, Loch Scavaig, or Dunluce, there is the same masterful repose and

harmony. The parts balance one another in stately regularity, and the

colours blend in pleasing dissimilarity.

As compositions, Thomson’s

contributions to the Provincial Antiquities of Scotland, eleven in

all, compare favourably in these respects with those of Turner—also eleven

in number—in the same work. Of the two we prefer the former. They want the

turmoil and bustle, the almost wild disorder so characteristic of Turner,

and often quite misplaced; but for dignity of style, truthfulness of

delineation, and pleasing balance of parts, they are in no way surpassed

by that great master.

That the genius of the two men

differed in some respects is no derogation to either. ‘One star differeth

from another star in glory’; and though a non-discriminating crowd

sometimes mistake an oil-lamp on a railway signal for one of the heavenly

bodies, the genius of these two representatives of English and Scottish

landscape in the first half of last century still shines clear and

unmistakable. They were both artistic geniuses of a high order. Men have

been challenged to define genius, and they have tried to do it without

being asked. Each individual of the great humans family is presumed to be

endowed by Nature with special tastes, inclinations, or dispositions. The

bent of their genius may lie in qualities of the mind developing

themselves in certain kinds of action or employment; and if special

success attends their efforts we count them fortunate and great. But there

are many who are clever and many who are successful in life whom we never

think of associating with this faculty. If, on the other hand, genius

consists in distinguished mental superiority, implying high and peculiar

gifts of Nature, impelling the mind intuitively to certain favourite kinds

of mental effort, and producing new combinations of ideas, imagery, and

form, we at once restrict to comparatively few this Heaven-sent power. As

one writer has put it—.’ Real genius of the perfect kind would be more

than one man could carry.’ Such genius as a man can possess is

fragmentary, never whole. He may have literary genius, and that is enough

for one; he may have artistic genius, that makes his work the admiration

of many generations; he may have a genius for massing great bodies of men

and bending their actions to his will; or his capacity for evolving from

subtle problems the true philosophy of life may entitle a man to the high

character of a Newton, a Napier, or a Euclid. Difficulty is the spur to

genius, and frequently develops out of mere cleverness some latent

Heaven-born power. The fact is, clever people can do nothing unless it is

a little difficult; they cannot see what lies directly under their noses,

and one of the truths so situated is, that perfect genius has never

existed. But if we cannot get perfection, a man may still be true up to

the limit of his capacity. Very often what is wanting in great men is the

balance-wheel of common sense, and the want of it frequently nullifies

much admirable effort. But the true genius is ever plodding, persevering,

never satisfied that perfection has been attained. In such method and

spirit John Thomson studied Nature; and as Nature’s interpreter his

success was undoubted.

There are few painters whose

landscapes have so much of reality, so much even of a local impress about

them, and which are at the same time so uniformly the fruit of abstraction

and combination— works of Art in the strictest sense of the word. Thomson

studied Nature to master its elementary effects, and combined his

abstractions into groups of his own. He would spend hours, we are told,

‘striving to make an exact portrait of a graceful or majestic tree or

rock—to catch the exact effect of some twilight gleam, or of sparkling

water trickling below foliage in a stray sunbeam. But when he set himself

to paint a picture, his object was to reproduce and group beautiful

images, not to make a map or a view of a precise locality. Hence his

landscapes are at once intensely Scottish in their character, and yet

scarcely one of them approaches to a facsimile of. any known locality. He

has left views of particular places; but they are all representations of

the scenes under the influence of accidental atmospheric effects, and as

the momentary mood of his own mind apprehended them.’

He never lost sight of Nature. His

most powerful and successful efforts, indeed, are evolved from a

profounder knowledge of natural scenery, combined with the effects of

light and shade, than was possessed by any of his contemporaries in this

country. He had a deep, rich sense of the beauties of colour and form,

though, owing to his never having studied the human anatomy, he was less

master of form than of colour. He possessed a wonderful power of imparting

the appearance of motion to air and water, which may be seen well

exemplified in such pictures in the National Gallery, Edinburgh, as

‘Ravensheugh Castle,’ ‘Aberlady Bay,’ and the ‘View on the Clyde,’ where

the motion of the waves as they dash against the rocks is given with

exquisite truthfulness.

This could only be acquired by close

watchfulness and rapidity of execution; by being much in the open, and

noting the changing effects as they flitted before him. ‘The best

unofficial education for an artist is,’ says William Bell Scott, ‘daily

sketching—keeping a pocket sketch-book. If he in this way records every

characteristic action, every beautiful feature or form he observes, not

only in the accidents of society, or active human life, but also in

vegetation, or among the lower animals, be will be real and natural in

expressing whatever he invents. Without the faculty of observation the

ideal becomes simply unreal.’

Thomson was continually noting

changing effects, and his sketch-books were full of suggestions for future

application; in fact, he was singularly successful in his sketches,

particularly in subjects demanding grandeur of treatment or breadth of

effect. He studied, too, the works of the older masters—Salvator Rosa,

Poussin, and Claude; but instead of submitting to the drudgery of the

schoolmen, he studied them only to discover and note what they had

actually done for landscape art. He examined their works critically, no

doubt, with the sole view of fixing a true starting-point for himself.

Speedily mastering their defects and peculiar excellences, he strove to

avoid the former, and as eagerly struggled to acquire the latter. With all

the disadvantage of enjoying only a month under Nasmyth, he was still, in

a true sense, a student of Nature and Art all his days. To these masters

may undoubtedly be attributed his knowledge of the laws of composition and

effect; but he could not well imitate them, for the simple reason that he

was devoted to the delineation of Scottish, not Italian scenery.

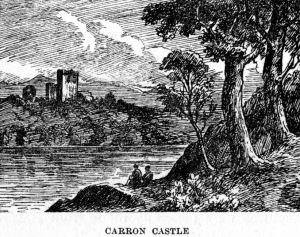

Occasionally

he indulged himself in Italian subjects, introducing pillared temples,

grottoes, waterfalls, etc., after the manner of Claude, Turner, and Andrew

Wilson, with occasionally wonderful evening effects, but we cannot say

they were always happy or natural. They generally are strained and lack

the impress of Nature’s inspiration. His

forte was to

portray, not the gorgeous landscape of the clear clime of Italy, but the

deserted castles of his native land. The striking towers and fortalices

along the varied Scottish coast, famed as the ancient retreat of the

champions of Scottish independence, and not unfrequently the refuge of

titled lawlessness, were the special objects of his study. Whether it was

the castle perched high on some bold cliff or headland, with stern black

rocks and the angry sea-waves dashing themselves impotently into spray at

their base, as at Dunstaffnage, Dunnottar, Tantalon, Turnberry, or Fast

Castle; or some lone peel or tower by the margin of peaceful river or

lonesome lake; or in a deep, umbrageous setting of green, as at Castle

Campbell, Brahan Castle, Newark Tower, Carron, Brodick, or Craigmilar,— in

either class of subjects he was equally at home. The pine was his

favourite tree, which he utilised freely in compositions in which it was

desirable to have a foreground fringe of foliage, and frequently they are

so introduced, we must admit, when the particular locality could not even

boast of such a feature. Consistency in this direction never troubled

Thomson, for, as Lord Young once remarked when this characteristic was

pointed out, he put in trees where it suited his purpose, just as he would

put in sea-gulls! He originated and shaped out for himself a style of his

own, but a style that prominently expressed Scottish characteristics.

Occasionally

he indulged himself in Italian subjects, introducing pillared temples,

grottoes, waterfalls, etc., after the manner of Claude, Turner, and Andrew

Wilson, with occasionally wonderful evening effects, but we cannot say

they were always happy or natural. They generally are strained and lack

the impress of Nature’s inspiration. His

forte was to

portray, not the gorgeous landscape of the clear clime of Italy, but the

deserted castles of his native land. The striking towers and fortalices

along the varied Scottish coast, famed as the ancient retreat of the

champions of Scottish independence, and not unfrequently the refuge of

titled lawlessness, were the special objects of his study. Whether it was

the castle perched high on some bold cliff or headland, with stern black

rocks and the angry sea-waves dashing themselves impotently into spray at

their base, as at Dunstaffnage, Dunnottar, Tantalon, Turnberry, or Fast

Castle; or some lone peel or tower by the margin of peaceful river or

lonesome lake; or in a deep, umbrageous setting of green, as at Castle

Campbell, Brahan Castle, Newark Tower, Carron, Brodick, or Craigmilar,— in

either class of subjects he was equally at home. The pine was his

favourite tree, which he utilised freely in compositions in which it was

desirable to have a foreground fringe of foliage, and frequently they are

so introduced, we must admit, when the particular locality could not even

boast of such a feature. Consistency in this direction never troubled

Thomson, for, as Lord Young once remarked when this characteristic was

pointed out, he put in trees where it suited his purpose, just as he would

put in sea-gulls! He originated and shaped out for himself a style of his

own, but a style that prominently expressed Scottish characteristics.

Caledonian skies, with all their

wonderful gradation of colour, of light and shade, from the coolest of

greys to the fiery glow of the setting sun, never failed to receive his

closest observation. There was,

indeed, almost no atmospheric effect

which our ever-varying climate presents which he had not noted. Early dawn

or golden sunset, noontide brilliance or moonlight glamour, the cold,

shivering sleet of the driving storm or the calm blue of the cloudless

summer sky, all found in him an equally faithful delineator.

We have already referred to

Thomson’s admirable rendering of water: whether it was the tiny stream

murmuring and sobbing over its pebbly bed, the majestic river, the deep

pool where the salmon lie, the ripple of the wavelets as they kiss the

yellow sand of the seashore, or the heaving billows charging the

relentless cliffs—in calm or in storm he was successful in all. No form or

aspect that water assumed ever came amiss to him, for, in motion or at

rest, he comprehended its most bidden characteristics and never failed to

represent them. There is a wonderful dash—a wild heave in his seas—and,

generally speaking, a grand purpose and design in his work, though

occasionally marred by what may be called slovenly execution. There is

nothing commonplace in his Art—even his worst—but everywhere thought and

fancy, if not absolute imagination, rising at times to the highest

artistic genius.

The studies for his pictures were

generally made from Nature in chalk and pencil, sometimes thinly washed

with colour; and not unfrequently, like other artists of his day, when

‘tallow dips’ were more in use than now, he made successful experiments in

light and shade with candle snuff. Water-colour as a medium had not then

attained to the brilliance, finish, and excellence of expression which now

distinguishes this beautiful branch of Art. The early water-colour art was

limited in its scope, being based upon the line and monochrome wash.

Thomas Girton, at the end of the eighteenth century, introduced the new

method of tinting to full colour and obliterating the outline, and bad he

been spared he would have been a powerful rival to Turner in this

particular medium; but, alas ! he died in 1802 at the early age of

twenty-seven. To get rid of outline altogether as an interruption of

colour and as practically non-existent in Nature has been the aim of our

best painters who have excelled in water-colour as a medium. For one

thing, the materials at the beginning of last century were not so well

made, and their supposed want of permanency caused artists to be diffident

as to their use. Turner emancipated himself from this] prejudice or

delusion, and with marvellous success showed the art-world what

extraordinary capabilities lay in water-colour. Thomson never attained to

the same excellence in this medium, though some of his water-colour

drawings are marked with much carefulness of finish and power of effect.

It

was in oil that Thomson excelled. He considered it as the only permanent

medium, and water-colour as merely a temporary material like pencil,

chalk, or candle snuff. But alas for the permanency of oil! It is the very

irony of fate that so many of the works of Thomson, and of nearly all the

artists of his day who worked in oil, should have suffered sadly from the

fault of the colourman, and have been in many cases thoroughly ruined,

while their watercolours remain as fresh as when they first left their

hand. This arose from the too free use of materials employed to give depth

and brilliancy to the colour, whose properties were not sufficiently known

or even suspected, but which time has proved to be

It

was in oil that Thomson excelled. He considered it as the only permanent

medium, and water-colour as merely a temporary material like pencil,

chalk, or candle snuff. But alas for the permanency of oil! It is the very

irony of fate that so many of the works of Thomson, and of nearly all the

artists of his day who worked in oil, should have suffered sadly from the

fault of the colourman, and have been in many cases thoroughly ruined,

while their watercolours remain as fresh as when they first left their

hand. This arose from the too free use of materials employed to give depth

and brilliancy to the colour, whose properties were not sufficiently known

or even suspected, but which time has proved to be

thoroughly pernicious. These were

asphaltum and megilp, which were mixed and used together; the former being

a mineral pitch or compact bitumen of a black or brown colour, with the

tempting property of giving a high lustre to the darker parts of a

picture; the latter, a gelatinous compound of linseed oil and mastic

varnish. The tendency of this compound to shrink under the influence of

heat is very great, and the sad condition in which some of the finest

works of Art of last century are now to be found, where this material was

used, is a warning to avoid the meretricious gloss which is of the earth

earthy. Thomson is not the only one whose work has suffered thereby. We

see the marks of it in the paintings of Reynolds, Gainsborough, Raeburn,

Macculloch, Hill, Lauder, and Sir George Harvey, many of whose finest

works have been irretrievably ruined.

Thomson’s practice was to lay a

foundation on his canvas of a substance composed of flour boiled with

vinegar, which he called ‘parritch,’ upon which he then worked in his

colours. If the ‘parritch’ were not sufficiently dried and hardened before

the asphaltum and other colours were applied, the tendency was to contract

and crack the painting more rapidly. Indeed, his reckless use of asphaltum,

even for glazing purposes, gives some truth to Sir David Wilkie’s

sarcastic remark, ‘Take from Thomson his asphaltum and his megilp, and

nothing remains!’ As a rule, the skies of his pictures have stood the test

of time better than any other part. Occasionally we may find a blue that

has slightly changed either to a dark opaque blue or greenish hue, but

this does not often occur, and where it does is no doubt due to the fault

of the particular pigment failing to retain its original purity. Generally

speaking, his greys are excellent, being pure and transparent, and nothing

can exceed the charming delicacy of some of his clouds, with their pale,

pearly shadows, so cool and yet so deep.

It

is said that during the process of painting he was in the habit of

repeating passages from the Greek, Latin, and English poets, that

approximately described the subject in hand, or the particular aspect

under which he proposed to represent it. The celebrated John Clerk, better

known under the designation of Lord Eldin, whose professional abilities as

a judge, joined to his exquisite taste in the Fine Arts, made him a most

congenial companion, would frequently spend hours in the minister’s

studio. Clerk, who was himself no mean artist, used, it is said, to

‘impress upon Thomson to be bold and resolute in painting, for the very

effort at boldness of expression contributed to strengthen the conceptions

of the mind.’ Thomson never forgot the lesson, and he was in the frequent

habit of quoting Clerk’s language to others and repeating it to himself at

his easel. He was never indeed above availing himself of a hint or

observation if given by a friend in a friendly spirit, especially if he

discovered in it a grain of sense or truth.

It

is said that during the process of painting he was in the habit of

repeating passages from the Greek, Latin, and English poets, that

approximately described the subject in hand, or the particular aspect

under which he proposed to represent it. The celebrated John Clerk, better

known under the designation of Lord Eldin, whose professional abilities as

a judge, joined to his exquisite taste in the Fine Arts, made him a most

congenial companion, would frequently spend hours in the minister’s

studio. Clerk, who was himself no mean artist, used, it is said, to

‘impress upon Thomson to be bold and resolute in painting, for the very

effort at boldness of expression contributed to strengthen the conceptions

of the mind.’ Thomson never forgot the lesson, and he was in the frequent

habit of quoting Clerk’s language to others and repeating it to himself at

his easel. He was never indeed above availing himself of a hint or

observation if given by a friend in a friendly spirit, especially if he

discovered in it a grain of sense or truth.

Thomson painted with great facility,

and frequently with rapidity, and would finish a pretty large canvas in

all its essential features in a few hours, leaving perhaps only a few

details such as figures in the foreground, or stray touches on buildings

or foliage till after it was dry. So hurried indeed was he in his work,

that we have been told by one who occasionally visited the manse, that

just before the time for the annual exhibition several pictures might be

seen out on the grass before the door to hasten the drying!

Work so done is, of course, open to

the imputation of imperfection, though not necessarily of ineffectiveness.

That a good deal of the deterioration that has befallen some of Thomson’s

work is to be attributed to these circumstances is undoubted. At the same

time, we must guard against the idea that his pictures have all a tendency

in this direction. This is not so. Many that we have seen are remarkable

for their freshness, purity of tint, and absence of any signs of cracking.

Judging from two of the extant

portraits of John Thomson, which both represent him at his easel, he

appears to have been very particular as to his garb, for even when at work

with his brush he always retained the orthodox clerical black coat, the

only precaution taken against accidental spots of oil or paint being the

upturned sleeves of his coat. He would never, however, it is said, either

on Sunday or Saturday, wear a white scarf or necktie, always preferring a

broad black scarf.

In his habits he was methodical and

regular, working on steadily and perseveringly without any regard as to

the disposing of his pictures, for, as we have already hinted, there was

very little of the commercial spirit in Thomson’s art. Once his friend

Bruce, the picture-dealer, took him a quantity of ultramarine, a colour

which then sold at a very high price—as much as £10 an ounce—which he

wanted him to buy. Thomson said he could not afford it as he had no money,

but the difficulty was got over by Bruce offering to take some pictures in

exchange. ‘Ah!’ said Thomson, ‘I will be very glad to deal with you on

these terms; help yourself, take as many as you think will pay for the

paint.’ On that occasion Bruce got several pictures away with him, any one

of which would now far more than pay for three times the quantity of

ultramarine for which they were then considered the equivalent. Even the

visits of friends caused no perceptible interruption to his art work. On

one occasion Professor Wilson (Christopher North) happened to be at the

manse, and expressed a desire to possess one of the minister’s pictures.

Thomson had none at the time which he thought quite suitable, ‘but,’ said

he, ‘I won’t be long in painting you one,’ and there and then he commenced

and all but finished a lovely view of Dunluce Castle, while the Professor

was beside him. This picture is still in the possession of the Professor’s

family, by whom it is highly prized, and it has been reproduced as one of

the illustrations to this volume, by kind permission of Mrs. Wilson, the

Professor’s daughter-in-law.

John Thomson is described by one who

knew him well as tall, well built, not stout and yet not slender; he had

an elegant carriage, which imparted to him an easy, gentlemanly demeanour,

and a winning manner most attractive to strangers—in fact, a jolly,

honest-looking, good-natured man; affable to the last degree; his beaming

countenance, with its fine rosy complexion, was, when he spoke, generally

suffused with a happy smile. One felt speedily at ease in his company, for

beneath the pleasant exterior and those bright, twinkling eyes of his,

there lay the kindly disposition, the sympathetic nature, the true honest

heart, without which all outward semblances are but shams; for, as Burns

truly says,

‘The heart ay ‘s the part ay

That makes us right or wrang.’

Like a great many clergymen of the

period—though it was by no means restricted to the ‘cloth ‘—Thomson was

much addicted to the habit of snuffing. It was a custom even more common

than smoking is nowadays, a snuff-box being an almost indispensable part

of a gentleman’s furnishings. It was certainly a custom which would have

been ‘more honoured in the breach than the observance,’ but the notion

prevailed that snuff acted in some stimulating way upon the nerves of the

brain, as whisky is supposed to revive exhausted physical activity, and

indeed medical authorities were frequently at great pains to enunciate its

importance and value in this connection. Dr. Gordon Hake humorously

describes snuffing as a ‘waking up the torpor so prevalent between the

nose and the brain, making the wings of an idea uncurl like those of a

new-born butterfly 1’ The late Earl of Stair, who when a lad was an

occasional visitor at Duddingston Manse, delighted us once with a

description and imitation of the minister’s

modus operandi in the performance of this

function. ‘He was,’ said his lordship, ‘a most voluble and artistic

snuffer; covering the hand which between finger and thumb contained the

pinch with his large red silk handkerchief, he would in resonant tones

magnify the importance of the action, and conclude with a grand flourish

of the silk.’

Thomson’s works are scattered far

and wide. They are to be found in the country residences of our nobility,

and not a few of the old families of Edinburgh and the neighbourhood have

treasured specimens to show, while some have found their way across the

Border, and are to be met with here and there in England.

Particularly we would mention the

fine collection possessed by the Earl of Stair [Thomson’s relationship to

the Stair family and to Professor Wilson linked them together in a very

close family bond, which it is pleasant to know is still remembered by

their descendants. Professor Wilson and North Dairymple, ninth Earl of

Stair, grandfather of the present respected Earl, were married to two

sisters, respectively Jane and Margaret Penny, so that they were

brothers.in-law by marriage; while Mr. Thomson’s second wife was the widow

of North Dairymple’s near kinsman, Martin Dalrymple of Fordell and

Cleland, second son of Sir William Dalrymple, Bart., of Cousland.]

at Oxenfoord Castle, including several of his best works, such as ‘Glen

Feshie,’ ‘Tantallon Castle,’ and ‘Castle Urquhart,’ than which it would be

difficult to find better examples. Reproductions will be found among our

illustrations.

The late Mr. Lockhart Thomson,

nephew of the artist, had a large and important collection of over thirty,

which since his death has been dispersed. Among these were such pictures

as ‘The Martyrs’ Tombs,’ engraved by William Bell Scott; ‘Carron Castle,’

‘Brahan Castle,’ ‘The Pass of Killiecrankie,’ ‘Fast Castle,’ and a ‘Sea

Piece with Battleships,’ the last-named said to be the combined work of

Thomson and J. M. W. Turner, while some of the smaller ones are gems of

Art.

The Right Hon. Lord Kingsburgh,

Lord-Justice Clerk, has a large and varied collection, consisting of not

less than forty-two specimens, some of them, such as ‘Fast Castle’ (an

engraved picture), ‘Cambuskenneth Abbey,’ ‘Innerwick Castle,’ ‘Stirling

Castle,’ ‘Crichton,’ ‘Conway,’ and ‘Roslin’ Castles, being excellent

examples. Several of these are reproduced in this volume.

The Right Hon. Lord Young, another

ardent admirer of Thomson’s work, is able to show some thirteen or

fourteen pictures from his easel. There, for example, we find his grand

painting of ‘Dunure Castle’ (etched by William B. Hole, R.S.A.), a large

view of ‘Duddingston House,’ ‘The Cuchullin Hills, Skye,’ ‘Tantallon

Castle,’ and an early but fine ‘View in Cumberland,’ after the manner of

Nasmyth.

The Right Hon. the Earl of Rosebery

is the owner of several local views at Dalmeny, notable for their careful

finish rather than for breadth of effect. As views of park scenery they

are very fine, the grouping and delineation of the trees being thoroughly

artistic.

In the splendid gallery of Thomson’s

works at Bowhill, Selkirk-shire, his Grace the Duke of Buccleuch is the

happy possessor of perhaps as rich and varied a collection as it has been

our privilege to examine. It includes such important works as ‘Newark

Castle,’ ‘Brodick Castle,’ ‘Ravensheugh Castle,’ ‘The Glen of Altnarie,’

and ‘Edinburgh from Inverleith House.’ As an evidence of the high

estimation in which the artist was held by the present Duke’s father and

grandfather, it may be mentioned that there are no less than thirty

specimens of his work now in possession of the family, many of which were

purchased direct from the artist.

After Mr. Thomson’s death his widow

removed to Edinburgh, taking with her a large and interesting collection

of his works in oil,

water-colour, charcoal, and crayons,

some of them unfinished. On her death, which occurred on 11th October

1845, such of these as had not been previously disposed of were sold by

public auction. By the public press of the time the event was the subject

of several appreciative notices, of which the following from the columns

of the Scotsman is a specimen. It helps us to judge of the

estimation in which Thomson’s work was held in Edinburgh at that date:—

‘The fine collection of this great

artist’s works, hitherto preserved by his family, is now about to be

broken up and dispersed by public auction in the saleroom of Messrs. Tait

and Nisbet. No man has done so much as Mr. Thomson to maintain the

character of native Art in landscape, and no man has more successfully

transferred to the canvas the grand and impressive features of his

country’s scenery. His pictures have also done much to educate the eye and

inform the judgment of his countrymen—to teach them that it is not a

slavish imitation of details which forms the great merit of a painter, but

the vigorous grasp which seizes the prominent and commanding features of

Nature, and without dissipating strength in their elaboration fixes them

at once upon the canvas. No one with any sympathy either for Nature or Art

can walk round the saloon where these pictures are exhibited without

acknowledging the high genius that inspires this great artist’s works. The

rudest sketch bespeaks freedom and power. Nature is not extinguished

beneath the heavy facts of mere detail; her great lineaments are here as

they address the eye and stir the fancy of the poet; and while we have the

boundless forest stretched before us, we can well spare the tedious art

that invites us to count its thousand leaves. To these and all such works

may well be applied the observation that they present us with Nature in

the spirit, not in the letter, for the letter killeth, but the spirit

maketh alive. We feel,’ says the writer very sensibly in conclusion, ‘that

we confer a benefit on the lovers of Art by directing their attention to

these great works, and even although they may not be disposed to enrich

their collections by purchasing from this source, let them embrace the

opportunity of at least viewing them before their final dispersion.’—

Scotsman, 11th April 1846.

If it be true that John Thomson’s reputation in the

place that once knew him so well is now perhaps somewhat obscured by the

galaxy of artistic genius which has since then given the Scottish School

of Painters a world-wide celebrity, do not let us forget that to him his

contemporaries, at all events, gave a deservedly first place.

Repeatedly do we find his works the subject of

laudation in the periodical literature of the day. In the pages of

Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, which spared no one, but attacked

everything and everybody with masterly vigour and freshness, he is by his

good friend Professor Wilson invariably held up to admiration as ‘the

first artist of his country.’

Here is how he appears to them in Christopher North’s

Noctes Ambrosianae. Referring to the Exhibition of 1824, whose merits

are being discussed by Ambrose, Tickler, Shepherd, and North, the Shepherd

breaks out with— ‘Oh, the pictures! I was there the day. Oh man, yon

things o’

Wulkie’s are chief endeavours. That ane frae the Gentle

Shepherd is just Nature hersel’.

Tickler.—’ Mr. Thomson of Duddingston is the best landscape painter

Scotland ever produced; better than either Nasmyth or Andrew Wilson or

Greek Williams. Some noble landscapes of his are the chief embellishments

of the Exhibition.’—Blackwood, vol. xv.

Again, in 1827, North declares:—

‘Mr. Thomson of Duddingston is the best landscape painter in Scotland.

THE MAN’S A POET.’

Shepherd.—’ I dinna like that picture o’ his at a’

o’ Loch Catrine frae the Gobblin’s Cave. The foreground is too broken,

spotty, confused and huddled—and what is worst of all, it wants character.

The chasm down yonner, too, is no half profound enough, and inspires

neither awe nor wonder. The lake itself is lost in its insignificance, and

the distant mountains are fairly beaten by the foreground, and hardly able

to haud up their heads.’

North.—’ There is truth in much of what you say, James, but still,

the picture is a magnificent one.’

Shepherd.—’ I wadna gie the "Bass Rock" for a

dizzen o’t (another picture in the same Exhibition). You may wee! ca’ it a

magnificent ane— and I wud wish, in sic weather, to be ane o’ the mony

thousand sea-birds that keep wheeling unwearied on the wind, and ever and

anon cast anchor on the cliffs—still solitary and sublime—a sea-piece,

indeed, worthy of being hung up in the Temple o’ Neptune.’

North.—’ Kinbane Castle (also an exhibit of 1827) is just as good,

and

Torthorwald Castle, Dumfriesshire, is the best illustration I ever saw

of Gray’s two fine lines—

"Now fades the glimmering landscape on the sight,

And all the air a solemn stillness holds."’

Shepherd.—’Mr. Thomson gi’es me the notion o’ a man

that had loved Nature afore he had studied Art—loved her and kent her weel,

and been let into her secrets, when nane were by but their twa sells,

where the wimplin’ burn plays in open spots in the woods, where ye see

naething but stems o’ trees, an’ a flicker o’ broken light interspersing

itself amang the shadowy branches—or without ony concealment in the middle

o’ some wide black moss—like the moor o’ Rannoch—as still as the shipless

sea, when the winds are weary, and at nightfall in the weather gleams o’

the setting sun a dim object like a ghost standing alane by its solitary

sel’— aiblins an auld tower, aiblins a rock, aiblins a tree-stump, aiblins

a cloud, aiblins a vapour, a dream, a naething.’

North.—’

Yes, he worships Nature, and does not paint with the fear of the

public before his eyes. It is a miserable mistake to paint purposely for

an exhibition. He and his friend Hugh Williams are the glory of the

Scottish Landscape School.’

North.—’

Yes, he worships Nature, and does not paint with the fear of the

public before his eyes. It is a miserable mistake to paint purposely for

an exhibition. He and his friend Hugh Williams are the glory of the

Scottish Landscape School.’

Again, in 1830 (April), we have the friends discoursing

together in Ambrose’s back parlour upon the Exhibition of that year.

Shepherd.—’Hae ye been at the exhibition o’

pictures by leevin artists at the Scottish Academy, Mr. North, an’ what

think ye o‘t?’

North.—’I look in occasionally, James, of a

morning, before the bustle begins, for a crowd is not for a crutch.’

Shepherd.—’But, ma faith, a crutch is for a crood,

as is weel kent o’ yours, by a’ the blockheads in Britain. Is ‘t guid the

year 1’

North.—’ Good, bad, and indifferent, like all other

mortal exhibitions. In landscape we sorely miss Mr. Thomson of Duddingston.’

Shepherd.—’ What can be the matter wi’ the

minister? He is no’ deid?'

North.—’God forbid! But Williams is gone: dear

delightful Williams, with his aerial distances into which the imagination

sailed as on wings, like a dove gliding through sunshine into gentle

gloom, with his shady foregrounds, where love and leisure reposed—and his

middle regions with towering cities, grove-embowered, solemn with the

spirit of the olden time—and all, all embalmed in the beauty of those deep

Grecian skies! Mr. Thomson of Duddingston is now our greatest landscape

painter. In what sullen skies he sometimes shrouds the solitary moors!’

Shepherd.—’ And wi’ what blinks o’ beauty he aften

brings out frae beneath the clouds the spire o’ some pastoral parish kirk,

till ye feel it is the Sabbath!’

North.—’ Time and decay crumbling his castles seem

to be warning against the very living rock,— and we feel their endurance

in their desolation.’

Shepherd.—’I

never look at his roarin’ rivers, wi’ their precipices, without thinking

somehoo or ither o’ Sir William Wallace. They seem to belang to an

unconquerable country!’

Shepherd.—’I

never look at his roarin’ rivers, wi’ their precipices, without thinking

somehoo or ither o’ Sir William Wallace. They seem to belang to an

unconquerable country!’

North.—’ Yes, James, he is a patriotic painter.

Moor, mountain, and glen—castle, hail, and hut—all breathe sternly or

sweetly o’ auld Scotland. So do his seas and firths roll, roar, blacken

and whiten with Caledonia from the Mull o’ Galloway to Cape Wrath. Or when

summer stillness is upon them, are not all the soft, shadowy pastoral

hills Scottish that in their still, deep transparency invert their summits

in the transfiguring magic of the far sleeping main ?’

Numerous extracts of a similar kind might be quoted

from the same gifted pen, all going to show the high estimation in which

Thomson’s work was then held.

Let another suffice, taken from an article by a

different writer in Blackwood, vol. xl. p. 76, on ‘The British

School of Painting.’ In this paper the writer, after a review of the works

of Turner, goes on to refer to Copley Fielding in London and John Thomson

at Edinburgh as typical men. ‘No one,’ he says, ‘will be so bold as to

deny to Fielding the merit of consummate delicacy in the management of his

pencil—a Claude-like richness in foliage and the happiest delineation of

the varying effects of coast scenery; or to Thomson a depth of shade,

vigour of conception, and strength of colouring which place him among the

most accomplished artists of the present day. But will either the one or

the other stand the ordeal with Poussin, Ruysdael, Claude Lorraine, or

Salvator Rosa? That is the question; and these truly eminent men will see

at once in what rank we estimate their genius, when we place them in line

with such compeers. And why should they not equal—nay, excel them? Why

should not the wild magnificence of the Scottish lakes, or the rich

furnishing of the Cumberland valleys, or the savage grandeur of the coast

scenery of Devonshire, inspire our painters as they have done our poets,

and produce a Scott, a Wilson, or a Southey in the sister art?’

In more recent times, and by writers of merit on the

subject of Art, there have been occasional references to Thomson’s genius

in such outstanding periodicals as the Art Journal and the

Portfolio. By them his work is recognised as of the highest excellence

and of undoubted value, because it told with effect on the Art culture of

his day to an extent perhaps which the work of few modern artists can

approach. It had its defects, no doubt resulting from occasional overhaste

and the use of pernicious material, but these were the accidents of

circumstances over which he had little controL ‘When newly painted,’ says

one writer, ‘his pictures were exceedingly rich and beautiful in colour,

and some still remain so. There is a grand purpose and design in his work,

though marred by what would nowadays be called slovenly execution.’

Another writer—Walter Armstrong — speaking of Thomson

as an artist says:

‘In

his painting he gave evidence of a truer gift for landscape than any other

Scotsman of his time. His fame ‘—referring more particularly to his

appreciation south of the Tweed—’ has suffered here through the presence

in the (London) National Gallery of an atrocious example of his work. Like

all amateurs he was very uncertain: now he would paint a landscape worthy

almost of Richard Wilson, and this he would follow up with a performance

feeble enough for a schoolgirl. His model seems to have been Gaspar

Poussin tempered by Claude and Wilson. As a colourist he was conventional,

but he often achieved a silvery harmouy which is very agreeable. Unlike

most amateurs he succeeded best when he tried least. Some of his more

sketchy pictures, in which the colour is put on freely, with a dexterity

and sympathy almost equal to Morland’s, hint at a mastery which is found

in none of his more ambitious 'pictures,' and, as an instance of this, the

writer refers to a small picture in the possession of the Earl of Wemyss,

exhibited by his Lordship in London in 1886, and now in the collection at

Gosford House.

‘In

his painting he gave evidence of a truer gift for landscape than any other

Scotsman of his time. His fame ‘—referring more particularly to his

appreciation south of the Tweed—’ has suffered here through the presence

in the (London) National Gallery of an atrocious example of his work. Like

all amateurs he was very uncertain: now he would paint a landscape worthy

almost of Richard Wilson, and this he would follow up with a performance

feeble enough for a schoolgirl. His model seems to have been Gaspar

Poussin tempered by Claude and Wilson. As a colourist he was conventional,

but he often achieved a silvery harmouy which is very agreeable. Unlike

most amateurs he succeeded best when he tried least. Some of his more

sketchy pictures, in which the colour is put on freely, with a dexterity

and sympathy almost equal to Morland’s, hint at a mastery which is found

in none of his more ambitious 'pictures,' and, as an instance of this, the

writer refers to a small picture in the possession of the Earl of Wemyss,

exhibited by his Lordship in London in 1886, and now in the collection at

Gosford House.

We have said sufficient, we think, to justify our

contention that Thomson must be recognised as occupying the front rank

among British masters of landscape Art, and being undoubtedly one of the

best which his country has produced. You may call him the Scottish Claude

or the Scottish Turner, or by any other borrowed name you will, but he has

individuality enough to stand on his own merits, or to be criticised for

his faults. These we have attempted honestly to discover and point out.

For him, as one has well said, ‘Art was a passion. The deep, tremulous

emotions, ever ready when not held down by a strong will to break forth in

a cry, or break down in a flood of tears, were the dowry of a truly

poetic, essentially artistic nature. As he looked out upon earth and sea

and sky, all seemed to stir with the gleam of God’s eye. Beauty was to him

God’s handwriting — a wayside sacrament to be welcomed in every fair face,

every fair sky, every fair flower; to be drunk in with all one’s eyes.’

The influence of such a man as Thomson cannot well die.

His name may be forgotten and his works in time may perish, but the

ever-flowing, ever-swelling stream of the nation’s culture must for ever

be enriched by the impetus his genius imparted to the Art ideas of his day

and generation. His teaching and example become in a measure imperishable,

for they have made their impress deeply on the Art life of the people.

Even as Scott and Burns have influenced our literature, so Thomson has

been a moulder of the Scottish School of Art. Such works as he has left us

are a priceless legacy which must not be lightly valued. Like great deeds,

which cannot die—

‘They with the sun and moon renew their light,

For ever blessing those that look on them.’