|

A QUAINT interest peculiar

to itself hangs about this old-world village on the northern slope of the

Cheviot Hills. The home of that mysterious nomad race who came in the

Middle Ages no man knows whence, Yetholm possesses an attraction of its

own for the Bohemian instincts of the wanderer. The road to it out of the

west, too, lies through a lovely country, whose every nook and spot has

some historic memory. From the valley of the Jed, south-eastwards among

quiet pastoral hills, the wanderer may linger upon the ancient Roman road,

forsaken by its builders fifteen centuries ago; and, if his senses be keen

enough, he may hear there still, far off as an echo through the ages, the

tramp of the departing legions. Weed and brier have made the, "Watling

Street" a wilderness, and for miles at places it is trodden now only

by the straying feet of rustic lovers. Then there are paths to be followed

down secluded lanes, where yellow straw from passing harvest carts has

caught in the high hedges among the crimson haws; and where wild

raspberries grow thickly under the woods amid dark-green broom and tangles

of the scarlet-hipped dog-rose.

In the little village of

Crailing the pedestrian, meeting cherry-cheeked children in pinafores and

satchels coming in twos and threes from school, may recall, as a contrast

to the place’s present state of peace, a dark day’s work that happened

there in 1570. On the night of Regent Murray’s assassination, Ker

of Fernihirst and Scott of Buccleugh had made a raid into the Border

counties of England; whereupon Lord Sussex, with the troops of Elizabeth,

marched, burning and slaying, into the lands of these barons; and, coming

upon the tower of Lord Ker’s mother, in the village there, committed it

to the flames, and its inhabitants to the last indignities at the hands of

the rude soldiery. The place was the chief seat of the ancient Border

family of Cranstoun.

Close by Crailing lies the

little hamlet of Eckford. It is musical now with village sounds—the

tinkle of the smithy, the hammering of the cartwright, and the low of kine;

but there, too, nevertheless, in bygone days, has passed the trail of fire

and blood. It was one of the places burnt by Ralph Evers under the

filibustering commission of Henry VIII. in 1544, when the English king was

seeking by such gentle means to induce the Scots lords to wed their infant

Queen Mary to his son.

Several legends of the

village, of another but not less typical character, are recounted by Sir

George Douglas in his New Border Tales. One of these, like so many

village traditions in Scotland, refers to Sabbath - breaking and the fate

of the Sabbath - breakers. Many years ago, it appears, there dwelt at

Eckford a certain sceptical and independent blacksmith. In every way but

one he is said to have been an exemplary workman. The single exception

arose from his conduct on the Sabbath. Sunday after Sunday, as the country

folk passed to church, they saw the smith at work, his bellows blowing and

his hammer ringing on the anvil as on any other day of the week. These

proceedings were not only shocking to his church - going neighbours, and

felt by his competitors in the countryside as the taking of a mean

advantage over them, but were looked upon as likely to draw upon the

perpetrator the actual wrath of Heaven. The smith meanwhile paid as little

attention to the indignation of the passers-by as to the possibility of

supernatural interference. A day of reckoning, however, came at last. One

Sunday morning, as the country-folk passed to church, they saw the smith

in his leathern apron, busy as usual over the glowing metal; the sparks,

if anything, flying faster from his stroke, and the anvil ringing more

defiantly than ever. But a few hours later, when the sermon was over and

the villagers came out of kirk, neither smith nor smithy, nor a vestige of

their belongings, was anywhere to be seen. The spot where the smithy had

stood—near the south-west corner of the field to the west of the manse—had

become a bog. Nothing was ever again seen of the smith, his wife, and

family, who had all disappeared; but many years afterwards, when the bog

was at last drained, the fate of the sceptical and self-sufficient workman

was put beyond all doubt by the discovery of a smith’s anvil.

Another incident, somewhat

less mysterious, of the punishment of sacrilegious transgression, is

chronicled of the same neighbourhood. It was in the year 1829, when, after

the revelation of the Burke and Hare murders, whispers of the doings of

the "resurrectionists," or stealers of the dead, were exciting

horror and fear in the country. On a night of late autumn a young packman,

known, on account of his smart and well-to-do personal appearance, by the

soubriquet of Dandy Jim, was passing Eckford churchyard. He had been

visiting a sweetheart in the neighbourhood, and, as frequently happens

upon such tender occasions, had been detained somewhat late. The moon,

however, had not yet risen, and the night was dark. The packman was not

much given to superstitious fears, but as he passed the churchyard his

attention was arrested by a mysterious light which appeared and

disappeared among the graves. He stood still to make out what the

appearance might mean; and presently he saw the light again, and heard a

curse and certain other sounds, which led him to believe that a body which

had been buried there on the day before was in process of being exhumed.

Stealing along the churchyard wall, in order to arrive nearer the scene of

operations, he suddenly came in contact with a horse and gig. Upon this

discovery a happy idea occurred to him. He untied the horse from the

fence, and with a kick in the ribs sent it galloping off across country;

then, while the terrified "resurrectionists" were ‘hastening

to secure their steed again, he leapt the wall, removed the corpse from

the black wrapping in which it had been rolled for removal, and

substituted himself in its place. His subsequent adventure in the hands of

the body-stealers culminated at a lonely part of the road near the village

of Maxwellheugh. By the time they had proceeded so far, the packman had

discovered his carriers to be a couple of dissolute tailors from Greenlaw,

nicknamed respectively "the Rabbit" and the "Hare."

Moreover, as they proceeded with their burden between them in the gig, he

had become aware, from various symptoms, that the courage of the two

thieves was ebbing rapidly.

"At last," says

the recorder of the incident, "the Rabbit, whose condition for some

reason or other, had for some time past been growing more and more acutely

distressing, could bear it in silence no longer, but broke out wildly—

"‘Hare! I’ll take an oath before a Justice of the Peace I felt

the body stir!’

"But the Hare’s

distress was even more extreme than that of his associate.

"Rabbit, man! Rabbit,

man!’ murmured he, in the hushed and solemn tones of dire mental

tribulation, ‘my mind misgives me, my mind misgives me, but we ha’e

mista’en our man. They must ha buried this one alive, I’m thinking;

for, as I’m a living sinner, the Corp is warm!’

"This was the moment

for which Jim had patiently waited. He now slowly lifted the cloth which

was about his face, and spoke in such sepulchral tones as he was able to

command—

"Warm, do

you say? And pray, what would you be if ye came frae where I ha’e

been?"

"The Hare saw the

supposed dead body move. To his heated imagination its action, as it

uncovered its face, bore a hideous resemblance to that of a dead man

rising from the grave at the last day. He heard the sepulchral tones which

addressed to him by name a pertinent and suggestive query; and he waited

for no more. With a bound, like jack-in-the-box, he leapt from the gig,

cleared the fence which bounded the road upon his side, and in a moment

afterwards was racing for his life across the open ground of Spylaw. At

the same instant ‘the Rabbit’ on his side slid to the ground,

scrambled through the hedge, and made for the covert of the High Wood of

Springwood Park as fast as his short legs would carry him."

Meanwhile the packman,

after a hearty laugh, put the horse’s head about and drove merrily home,

having by his strategy at once become possessor of the unclaimed horse and

gig, and discovered enough to frustrate a widely organised conspiracy of

body-snatching.

Such is the story of the

"resurrectionists" connected with Eckford churchyard, and it is

here given at some length, as affording a typical example of the kind of

local tradition of more modern times current in village and hamlet

everywhere throughout the country.

Hanging by the kirk door at

Eckford, as by the gate at Abbotsford, may still be seen the "jougs,"

or iron collar, used here in former days, chiefly as a punishment for

those who came under church discipline. The last person upon whom they

were used, being short of stature, it appears, slipped from the stone upon

which he was mounted; and when, at the usual point of the service, the

beadle came to conduct him before the congregation for ministerial

admonition, was found hanged. After that tragic occurrence the punishment

of the "jougs" was given up.

Beyond Eckford the road

winds up by the Kale Water, one of the districts laid waste by Sussex in

1570, and by Ralph Evers in 1544, upon which latter occasion it is

recorded that thirty Scots were slain, and the Moss Tower smoked very

sore. The water is famous at the present day among anglers.

The valley of the stream

further on, the Bowmont Water, which comes down among the hills to the

right of the road, is the scene of another characteristic tradition —

one of those strange Border legends which in other days would have been

woven by some wandering minstrel into a ballad. It is the story of a

shepherd’s daughter, the beauty of the district, who, after slighting

the love of all the lads of the neighbourhood, gave her heart to a

somewhat forbidding and mysterious stranger. The tradition runs that on

keeping tryst with this lover one night in a lonely glen, she arrived

before the appointed hour; and, having climbed for caprice into a tree to

see how he would bear her delay, she beheld him deliberately dig her

grave. The wood—some say the actual tree—at which the incident

occurred is still pointed out; and the truth of the story is vouched for

by the fact that a lady, a member of one of the noble families of the

district, personally knew a daughter or grand-daughter of the girl.

At this point last night,

as the Cheviots rose in front—grey, rounded hills and far-lying valleys—

the sun went down in the yellow autumn sky behind; and presently could be

felt the cool air of night, champagny and full of strong life, blowing

bold and free out of the mountains. The keeps of old Border barons were to

be seen from the road— Corbet Tower and the fortalice of the Kers of

Cessford—grim memorials of the feudal past, and of the strong hands that

were needed once to hold their own among these hills. After passing the

village of Morebattle—itself mentioned more than once in the records of

Border warfare—the way ran under trees, and the road became higher and

more lonely in the darkness, under the dim and distant sparkle of the

stars. At last a light here and there began to gleam in the valley to the

right, and presently, far in front, appeared the shining inn lantern of

the Gypsy village.

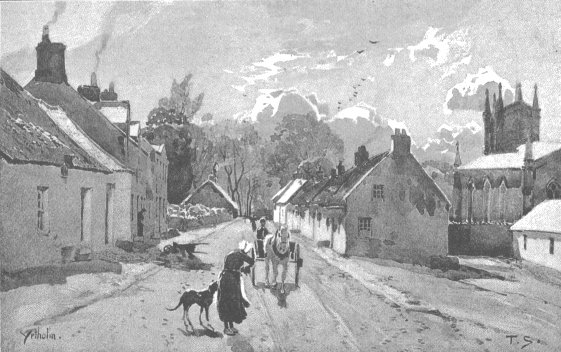

Kirk Yetholm

It was too dark and late

then for seeing anything of Yetholm, and under the shadows of night there

was room for all sorts of imaginings as to the life that might be found in

so romantic a spot. Here, if anywhere on the Borders, something ought to

remain of the free, rough existence of long ago, with perhaps a touch

added of Eastern picturesqueness. Might there not be the ruddy gleam of

camp fires at the doors of turfy huts, the savoury smell of unpaid-for

supper in the air, and dusky featured men and women moving among the

lights and shadows? Might there not be laughter and merriment, the accents

of a strange tongue, the glimpse of some Gypsy beauty? All these

possibilities were dispelled, however, when mine host of the Swan

explained that, owing to the recent laws against vagrancy, the Gypsies

have all but disappeared even from their own village of KirkYetholm; while

as for Town-Yetholm here, divided from the other by the Bowmont Water, it

never was a Gypsy village at all.

And as the mountain mists

begin to rise, and the sun every moment shines more brightly in a sky of

deepening blue, the details of the spot can be made out. A gunshot up the

mountain side opposite clusters the Gypsy "town," the more

ancient and interesting of the two villages. Its low mossy-roofed "biggins"

are scattered picturesquely about the irregular village green—the

thatched inn, with swinging sign, standing a little out from the rest; and

altogether, with the mountain ascending still dark and dewy above, it is

probably, as it stands at the present day, a fair example of the ancient

Border hamlet.

The nearness of the

dividing line between England and Scotland was doubtless in bygone days

deemed a great advantage by the dwellers here. By the road up the hillside

at hand, any one who might be "wanted" could escape the arm of

Scots justice in less than half an hour; and the spot would form a

convenient retreat for refugees from the English side. For here dwelt

Ishmael.

A nomad race like the

Arabs, these wanderers journeyed hither as to a Mecca. For at Yetholm they

had a sovereign—a potentate who ruled by the divine right of the quick

brain and the strong arm.

A race without a literature

and almost without a history, the Gypsies, notwithstanding the researches

of science, and the sympathetic study of men like George Borrow, remain to

the present hour something of a mystery in Europe. One thing ascertained

about them is, that throughout the countries of western civilization their

language, though divided into various dialects, is substantially one

tongue, and has been proved to be a Hindoo dialect. When or from what part

of India they came, however, remains unknown. One thing certain about them

is, that they were not Egyptians, as they once professed, ‘and were wont

to be believed. From the words embodied in their speech it is gathered

that they made their way into Europe through Persia, Armenia, and Greece.

Probably it was they who were known in Greece in the times of Homer and

Strabo and it was probably they, descendants of the race of Simon Magus,

who at Constantinople in the 11th century are reported to have slain wild

beasts by their magic arts in the presence of Bagrat IV. In Austria in the

12th century they were recognised as the actual descendants of Hagar and

Abraham. Professing to be pilgrims of the Christian faith thrust out of

Egypt by the Saracens, they appeared during the 15th century in bands

before the walls of one capital of Europe after another, generally headed

by a chief, mounted and gorgeously dressed, who gave himself out to be

Count, Earl, or Duke of Little Egypt. So high, indeed, was the estimation

in which they were sometimes held, that one of their "kings" was

interred with regal honour by the side of Athelstane, at Malmesbury Abbey,

in 1657. In no country, however, were they better received than in

Scotland. As early as the time of William the Lion (1165-1214) a Scottish

charter has been found containing mention of Tinklers. In 1505 James IV.

gave Antonius Gagino, Count of Little Egypt, a letter of commendation to

the King of Denmark; and in 1540 James V. subscribed a writ in favour of

"oure louit Johnne Faa, Lord and Earle of Littill Egipt," giving

him jurisdiction of life and death over his own people. In the following

year, however, their pilfering and turbulent disposition having become a

trouble to the country, they were banished from the realm on pain of

death; and several cases are on record in which, for contravening this

law, members of the clan were sentenced, the men to be hanged, the women

drowned, and such of the latter as had children to be scourged through the

streets and burned in the cheek. Readers of Quentin Durward will

remember the similar summary treatment of Gypsies in France in the time of

Louis XI. Notwithstanding such fearful punishments, however, they appear

to have remained in the country—a merry, careless, good-humoured, but

passionate people—practising their arts of working in metal and horn,

busying themselves with horse-dealing and horse-stealing, and equally

famous for their proficiency in music and their profession of ability to

read the past and future of men’s lives. In 1530 it is on record, among

the court festivities of James V., that certain Gypsies "dansit

before the King in Halyrudhous." The latter pursuits in particular

were everywhere the profession of the women.

Here in Kirk-Yetholm,

sometime towards the end of the 17th century, was born Jean Gordon, wife

of the Gypsy chief Patrick Faa, who survives for the reading world in the

person of Meg Merrilees in Guy Mannering. Her fate and the fate of

her family afford an example of the treatment too often suffered as well

as deserved. For burning the house of Greenhead, her husband, Patrick Faa,

was whipped through Jedburgh, stood for half-an-hour at the cross with his

ear nailed to a post, had both ears cut off, and was finally transported

to the American plantations. In 1714 her son, Alexander Faa, was

murdered by another Gypsy. The murderer escaped from prison, but was

dogged from Scotland to Holland, and from Holland to Ireland, by the

murdered man’s mother; and finally, at her instance, was brought to

justice on Jedburgh Gallowhill. Jean’s other sons, after many

depredations, were hanged at Jedburgh all on one day—their fate, it is

said, being decided by the casting vote of a juryman who had slept

throughout the discussion of the case, but who suddenly waked up with the

words, "Hang them a’!" Jean was present at the trial, and upon

hearing the verdict is said to have exclaimed "The Lord help the

innocent on a day like this!" She herself was finally ducked to death

for her Jacobite leanings by the cowardly rabble of Carlisle, continuing

so long as she could get her head above water to cry out "Charlie

yet! Charlie yet."

Jean and her granddaughter,

Madge Gordon, were alike of imposing appearance, over six feet tall, with

bushy eyebrows, aquiline nose, and piercing eyes, corresponding in all

respects to what popular imagination pictures as the proper bearing of a

Gypsy Queen.

In the end of last century

the chief of the KirkYetholm gypsies was a later descendant of Jean

Gordon, who rejoiced in the somewhat picturesque title of Earl of Hell. It

was he who once very narrowly, by a mere lucky leniency of the jury, was

acquitted in the High Court of Justiciary, and whom the judge in

consequence informed significantly that he had that day "rubbit

shouthers wi’ the gallows," and warned not to venture the

experiment again.

The different tribes of

gypsies, no less than the different clans among whom they dwelt, had

feudal combats among themselves. One of these battles occurred on 1st

October, 1677, near the house of Romanno in Tweeddale. There the Shaws and

the Faas, on their way to fight the rival Baillies and Browns, themselves

fell out, and fought to the death. Old Sandy Faa and his wife, then about

to give birth to a child, were killed; and another brother, George Faa,

desperately wounded; for which transaction old Robin Shaw and his three

sons were hanged in the Grassmarket at Edinburgh in the February

following.

Of Billy Marshall,

afterwards the Gypsy king of Galloway, a well known story is told. He was

serving in the ranks under Marlborough in Germany in 1705, when one

day he went to his commanding officer, one of the M’Guffogs of Roscoe,

an ancient Galloway family, and asked if he had any message for home. The

officer inquired whether there was any messenger going, whereupon Marshall

answered— Yes, he intended himself to be at Keltonhill Fair, at which it

had always been his rule to be present. The officer, says Dr Chambers, who

recounts the story, knew his man, and Billy appeared at Keltonhill Fair as

usual.

A Gypsy enterprise of the

romantic sort which the popular mind attributes to that mysterious people,

furnishes the subject of one of the best known ballads of Ayrshire. The

scene of the ballad was Cassillis House, on the banks of the Doon, before

whose door still stands the ancient Dule-Tree or Tree of Sorrow. The

heroine was some fair and frail Countess of Cassillis, wife of a chief of

the Kennedys, and tradition avers that Johnnie Faa, otherwise Sir John

Fall, had been her lover before her marriage.

JOHNNIE FAA.

The gypsies cam’ to our

good lord’s yett,

And O but they sang sweetly;

They sang sae sweet and sae very complete

That doun cam’ our fair lady.

And she cam’ tripping down

the stair,

And all her maids before her;

As soon as they saw her weel-faured face

They cuist the glamourye’ o’er her.

O come with me," says

Johnnie Faa,

"O come with me, my dearie;

For I vow and I swear, by the hilt of my sword,

That your lord shall nae mair come near ye."

Then she gi’ed them the

red red wine,

And they gi’ed her the ginger;

But she gi’ed them a far better thing,

The gowd ring aff her finger.

"Gae tak’ frae me

this gay mantle,

And bring to me a plaidie;

For if kith and kin and a’ had sworn,

I’ll follow the gypsy laddie.

"Yestreen I lay in a

weel-made bed,

Wi’ my gude lord beside me;

This night I’ll lie in a tenant’s barn,

Whatever shall betide me!"

"O haud your tongue, my

hinny and my heart!

O haud your tongue, my dearie!

For I vow and I swear, by the moon and the stars,

That your lord shall nae mair come near ye."

But when our lord cam’

hame at e’en,

And speired for his fair lady,

The ane she cried, and the other replied,

"She’s awa’ wi’ the gypsy laddie!"

"Gae saddle to me the

black black steed,

Gae saddle and mak’ him ready;

Before that I either eat or sleep

I’ll gae seek my fair lady."

"O we were fifteen weel-made

men,

Although we werena bonnie;

And we were a’ put down for ane,

A fair young wanton lady."

According to tradition the

lady when brought back was first, by a refinement of cruelty, compelled to

witness from a window the dying agonies of the gypsy party, including her

disguised lover, on the Dule-Tree; she was then divorced by her lord a

mensa et thoro, and was finally imprisoned for life in the castle of

Maybole. There to this day, far overhead above the street, is pointed out

the window of the room in which she was confined, and in which she

occupied her leisure in working the story of her flight in tapestry. The

Earl in the meanwhile, it is said, married another wife.

So late as the year 1878

Queen Victoria was welcomed at Dunbar by a gypsy queen. The latter is

recorded to have been "dressed in a black robe with white silk

trimmings, and over her shoulders a yellow handkerchief. Behind her stood

two other women, one of them noticeable from her rich gown of purple

velvet; and two stalwart men conspicuous by their scarlet coats."

But now the last of the

Romany Queens is dead—a woman who, says the swarthy innkeeper of Kirk-Yetholm,

could read a man’s soul at a glance; and there will probably never be

another. [For an account of Queen Esther Faa-Blythe. her assumption of the

regal state, &c., as. well as much else that is interesting on the

subject of the Gypsy race, see The Yetholm History of the Gypsies, by

Joseph Lucas, Kelso, 1882.] The "deep" Romany blood is being

dulled by mixture with the Saxon strain, and the old instincts are dying

out. The little slated cot of the queen, with its single window and door,

stands empty now and forsaken in its own plot of ground at the head of the

village— a humble home, surely, for royalty. From its door,

nevertheless, as the morning mists slowly melt and disappear under the

spell of the sun, there is a view discovered of rolling hill and valley,

of stream and farm, that fills the eye with beauty and the heart with

strong content. With this before her, and, closer by, the dew of the

mountain glittering jewel-like on every grass blade—amid the solemn

stillness, the large hill air, and the glad sunshine, it may be surmised

that, perhaps, after all, the gypsy chose aright in loving and preferring

for her palace roof the arch that had covered her race in all their

wanderings—the blue dome of everlasting heaven.

|