|

ASLANT upon the side of its historic bill, the

Dunion, clings the steep street of this gallant old Border town.

Picturesque and irregular, with the castle at its head and the river

crossing its foot, the place was a fit home for the sturdy burghers whose

stout hearts made it famous. A dozen times, in days gone by, was the

stronghold harried with fire and sword. But when the harrying was over,

the inhabitants, undaunted, only gathered back again like wasps to their

byke; and in Border battles to the last the shout of "Jethart ‘s

here!" heralded dire havoc and slaughter. For the race who dwelt in

Jedburgh knew well, father and son, how to swing their home-wrought

battle-axes.

A rough-and-ready race these burghers were, as suited their day. Deeds,

not words, made judgment here; while so prompt was its execution that

"Jethart justice" rose to be proverbial, and the popular epigram

spoke of the burgh as the place—

Where in the morn men hang and draw,

And sit in judgment after.

Here, in feudal times, the Border Warden dealt March law. Close by the

town, in August 1388, gathered the forces for that raid into

Northumberland which culminated on the moonlit field of Otterbourne; and

ten miles out to the south, over the Dunion, lies Carter Ridge, the scene

of the conflict between the opposing wardens in 1575, known in history and

celebrated in song as "The Raid of the Reidswire "—one of the

many contests decided by the timely arrival of the burghers of the Jed.

Among old customs which give a glimpse of the temper of the townsfolk

as reflected in the sports of their children, remains to the present day

the somewhat rough pastime of "the callants’" or "Candlemas

ba’," played once a year through the streets by the "doonies"

and the "uppies" among the schoolboys. Formerly the privilege of

throwing off the first ball was given to the boy who brought the largest

offering to the rector of the grammar school; but some years ago the

School Board abolished the custom. The last "king" was Master

Celledge Halliburton.

Allan Cunningham has a ballad on the fate of a wandering minstrel of

earlier times, which affords a picture alike of the laughing merriment and

the sharp justice which characterised the life of Jedburgh in days gone

by.

RATTLING WILLIE.

Our Willie‘s away to Jeddart,

To dance on the rood-day;

A sharp sword by his side,

A fiddle to cheer the way.

The joyous tharms o’ his fiddle

Rob Rool had handled rude,

And Willie left New Mill banks

Red-wat wi’ Robin’s blude.

Our Willie ‘s away to Jeddart:

May fleer the saints forbode

That ever sac merry a fellow

Should gang sac black a road!

For Stobs and young Falnash,

They followed him up and down—

In the links of Ousenam Water

They found him sleeping soun’.

Now may the name of Elliot

Be cursed frae firth to firth!

He has fettered the gude right hand

That keepit the land in mirth;

That keepit the land in mirth,

And charmed maids’ hearts frae dool;

And sair will they want him, Willie,

When birks are bare at Yule.

The lasses of Ousenam Water

Are rugging and riving their hair,

And a’ for the sake o’ Willie—

They‘ll hear his sangs nae mair.

Nae mair to his merry fiddle

Dance Teviot’s maidens free:

My curses on their cunning

Wha gar’d sweet Willie dee!

The hero of this ballad, whom Professor Veitch thinks the same

personage as Burns’s ‘Rattlin’ Roarin’ Willie,’ and the subject

of a love song in Herd’s Ancient Scottish Ballads, was, according

to Cunningham, "a noted ballad-maker and brawler," whose

"sword-hand was dreaded as much as his bow-hand was admired."

His fate was the result of a quarrel with another minstrel, Robin of Rule

Water, on the respective qualities of their playing, in which Robin was

slain. Scott, in ‘The Lay of the Last Minstrel,’ makes the old harper

refer to Willie as his master.

"He knew each ordinance and clause

Of Black Lord Archibald’s battle laws,

In the old Douglas day.

He brooked not, he, that scoffing tongue

Should tax his minstrelsy with wrong,

Or call his song untrue.

For this, when they the goblet plied,

And such rude taunt had chafed his pride,

The bard of Reull he slew.

On Teviot’s side in fight they stood,

And tuneful hands were stained with blood;

Where still the thorn’s white branches wave

Memorial o’er his rival’s grave.

Why should I tell the rigid doom

That dragged my master to his tomb;

How Ousenam’s maidens tore their hair,

Wept till their eyes were dead and dim,

And wrung their hands for love of him

Who died at Jedwood Air ?"

At no time has the town long been left without a glint of the light of

history, from the day when the Scots King Donald defeated Osbert of

Northumbria and the refugee Picts close by on the banks of the Jed. The

castle was a favourite residence of the Scottish kings in the prosperous

period before the Wars of Independence. Here Malcolm IV., "the

Maiden," as he was called, grandson and successor of the wise David

I., died in 1165. And here occurred the second marriage of Alexander III.,

the last of the Celtic royal line.

Regarding this marriage a strange legend has been handed down, which

exhibits in tangible shape the national misgiving of that time, and which,

as an omen of disaster, forms a curious parallel to the legend of the

apparition which was seen, in St Michael’s Kirk at Linlithgow, by James

IV. and his court before the departure for Flodden.

Alexander III., the last of his house, was widowed and childless, and

the succession to his throne depended upon the fragile life of his

granddaughter, the infant Princess of Norway. The king, accordingly, was

urged to marry again, and, yielding to the solicitations of his nobles, he

at last espoused Joleta, daughter of the Count of Dreux. The nuptials, as

has been said, were celebrated at Jedburgh, and on the evening of the

marriage day the rejoicings culminated in a great masked ball in the

Abbey. In honour of the occasion the nobles and prelates of Scotland put

forth their best efforts. Celtic and Cymric, Saxon and Norman chivalry—

all the different elements of the kingdom, as yet unfused into one nation

by the Wars of Independence—contributed to make up the magnificent

spectacle. And in the midst, with his bride, appeared Alexander himself,

the wise statesman and warlike king, who, twenty years earlier, at the

great Battle of Largs, had freed Scotland for ever from the encroachment

of her ancient foes, the Norse. Never had so magnificent an assembly been

seen before in Scotland. The occasion was auspicious, and, perceiving in

the event of the day fair promise that their fears for the consequences of

a disputed succession would presently be set at rest, the Scottish lords,

it may be imagined, unbent to the gaiety of the hour; and courtly smiles

and gallant speeches surrounded the fair young queen from whom so much was

expected. It was when the stately revels were at their height, and the

pageant on the floor of the Abbey was at its gayest, that suddenly, to the

awe of the onlookers, there became visible the apparition of a ghastly

figure. It glided silently amid the throng, seemed to join for some

moments in the dance, and then vanished as silently and swiftly as it had

appeared. This omen, occurring when it did, was regarded as a dark presage

of troubles which were presently to descend upon the kingdom — a

foreboding which was all too certainly fulfilled. In the following year,

by the fall of Alexander III. over the cliffs at Kinghorn, Scotland was

plunged into the longest and most devastating of all its wars.

High behind Jedburgh, over the Dunion, on the cliff above the river at

the farm of Lintalee, lie the remains of the impregnable camp held in

Bruce’s time by "the good Lord James" of Douglas. Barbour

describes it in his famous historic poem.

Now spek we of the Lord of Douglas

That left to kep the marchis was.

He gert set wrychtis that war sleye

And in the halche of Lyntailé

He gert thaim mak a fayr maner:

And quhen the howssis biggit wer

He gert purway him rycht weill thar;

For he thowcht to mak ane infar

And to mak gud cher till his men.

From this eyrie again and again Douglas sallied, at every sally dealing

some deadly blow to the enemies of his country, till he had not only

brought all the eastern Border to the king of Scotland’s peace, but till

the mere mention of his name had become a terror:

The drede of the Lord of Dowglas,

And his renoune, sa scalit was

Throw-out the marchis of Ingland,

That all that thar-in war wonnand

Dreci him as the fell dewill of hell;

And yeit haf Ik herd oft-syss tell

That he sa gretly dred wes than

That quhen wiwys walde childre ban

Thai wald, rycht with an angry face,

Betech thaim "to the Blak Douglas."

After an alien occupation, the burghers themselves, Spartan-like,

destroyed Jedburgh Castle in 1409, swearing that their enemies, the

English, should never keep a garrison again in their town. The six

bastille houses built then in the castle’s stead have also long ago

disappeared, though in 1523 they, along with the Abbey, still held out

when Norfolk and Dacre had stormed and burned the town. The site of the

castle is now marked by the dark walls of the battlemented prison.

Like a gleam of sunshine through the driving storm of Jedburgh story is

the episode of Queen Mary’s visit here. Whether one read in it the

unreflecting chivalry of the generous Stuart blood, or, as her detractors

fain would do, the flame-gust of a guilty passion, there remains about it

that charm of romance which ever followed the footsteps of the fair,

unfortunate queen. Mary, the story runs, was holding a court of justice in

Jedburgh, when tidings arrived that her warden, Lord Bothwell, had, in the

execution of Border duty, been wounded seriously in the hand. One can

imagine a hundred thoughts as the Queen’s at the news. The Royal

authority itself had been insulted in the person of its warden—it was

the Royal hand which should vindicate the outrage. Perhaps, alas! the more

tender fear of a woman’s heart was there. The Stuart race, however, were

ever prompt in action, and, whatever may have been her thoughts, she did

exactly what her father, the gallant Fifth James, would have done—closed

Court, took horse, and rode to the scene of trouble. Hermitage, where Lord

Bothwell lay, was twenty miles distant, and she rode there and back in the

same afternoon. No wonder that her strength was exhausted. In a thatched

and steep-roofed old house at the town foot, now being fitted up as a

storehouse of Border relics, is still to be seen the room where she lay

ill for some weeks afterwards. They keep yet, in an attic there, the

tattered remains of her chamber arras.

Queen Mary's House

It is a quaint old house, with low stone passages and small deep-set

windows, an escutcheon being still legible above the door; and it is not

difficult to imagine the fair young queen — she was only twenty-four—in

the early days of her convalescence, moving about that sunny riverside

garden, with the solicitous chivalry of all her little court about her.

Once, at least, amid her later troubles the memory of that time came back,

and in bitterness of heart she is said to have exclaimed, "Would that

I had died at Jedburgh!

There is another garden somewhere about Jedburgh—the garden of that

"Esther, a very remarkable woman," who could "recite Pope’s

‘Homer’ from end to end," whom Burns, on his Border tour, was

taken to see. There, as he relates in his diary, he walked apart with that

"sweet Isabella Lindsay," in the pleasure of whose conversation—

"chit-chat of the tender kind "—the poet discovered that he

was "still nearly as much tinder as ever." There he gave her a

proof print of his likeness, and records that he was thanked with

"something more tender than gratitude." In fact, it was

evidently the scene of a very pretty little love affair.

In Jedburgh to the present day the Queen’s judges hold assize; and it

was here that the young advocate Walter Scott made his first appearance as

a pleader in a criminal court. It is recorded that he got off his man, a

veteran poacher, and that when, on hearing the verdict, he whispered to

the fellow, "You‘re a lucky scoundrel !" he was naïvely

answered, "I’m just a’ your mind, and I‘ll send ye a maukin

[hare] the morn, man."

Wordsworth once lodged in Jedburgh—the house is pointed out; and on

the eve of his raid into England, in November, 1745, in the flush of his

hopes and on the curling foam-crest of his fortunes, the last of the

lineal Stuart race, Prince Charles Edward, stayed a night or two in the

town. The place claims a line as well in the history of science, for it

was the birthplace of Sir David Brewster.

Not the least touching, if perhaps the most recent literary interest of

Jedburgh is its connection with Thomas Davidson, who now, through his ‘Life’

by Dr James Brown, occupies a place as the representative of a national

type, the Scottish Probationer. Davidson was born at Oxnam, a few miles to

the south of the town, and his family lived for a time also at Ancrum,

close by; but after his career of brilliant promise at college and as a

probationer, or licentiate of the church, it was to his father’s later

cottage of Bankend, close to Jedburgh, that he came home to die. Most of

his letters—the letters which lend such distinctive charm to his

biography—were written from this cottage; and here at last occurred the

final episode of his life. Davidson’s connection with Alison Dunlop—the

beautiful love-story which forms one of the most touching features in the

Probationer’s career—was altogether unknown to his nearest relatives

till he was on his death-bed. At last, however, when it was too late, the

secret was disclosed, and she was sent for. She arrived from Edinburgh on

the day after his death, when the passionate up breaking of her highly

wrought nature was a revelation even to the sorrowing parents. As the old

father himself has since described it, "Sic grief was never

seen."

Davidson, with true poetic feeling, had sung the charm, the spell of

the Border hills, and in his lines, ‘And there will I be buried,’ he

put into words the last instinct of the Borderer :—

Tell me not the good and wise

Care not where their dust reposes—

That to him in death who lies

Rocky beds are even as roses.

I ‘ye been happy above ground;

I can never be happy under,

Out of gentle Teviot’s sound;

Part us not, then, far asunder.

Lay me here where I may see

Teviot round his meadows flowing,

And around and over me

Winds and clouds for ever going.

Even down to recent times, Jedburgh has ecclesiastical associations of

no small importance. It was in the Grammar School here that the famous

Samuel Rutherford learned his letters; and Jedburgh was the scene of the

labours of the younger Boston, one of the founders of the Relief Kirk in

1757.

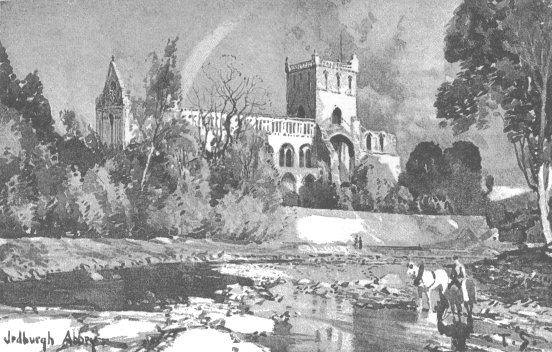

Jedburgh Abbey

But towering grey and venerable above all the roofs of the town,

halfway up the steep main street, rises the ruin of the ancient abbey.

Surrounded by pleasant, old-fashioned houses, with quiet gardens, where

yellow and pink roses are aflower upon the walls, that great carved cross,

mute record of the aspirations of ages long forgotten, raises its

sculptured sides in an inclosure of ancient graves. For three hundred and

fifty years the rising sun has kissed these broken cornices, and the rain

and dew have wept upon that desecrated altar, as if in pity for the

glowing souls whose dreams of sculptured beauty are, with these crumbling

walls, sinking to decay. The vandal has been here, as at Melrose, and has

broken in pieces the beauty he was too rude to understand. But time, with

healing touch, has wrought a fuller beauty and meaning than before into

the place. Of yore, no doubt, a stillness strange and sweet must have

fallen upon the spirit of the warlike burgher of the town as once in a

while he knelt on the quiet pavement, while from afar within rose amid the

shadows the chime of censers and the chant of priests. But no less to-day,

with its added memories of blood and fire, and its silent lesson of the

centuries, does the abbey remain a place for reverent thought. Overhead

rises the blue span of heaven’s own Norman arch, and for an altar.lamp

in the midst swings the dazzling sun-orb itself, burning at the throne of

God.

The white-stoled Premonstrentian monks of Jedburgh were men of war as

well as of religion, and more than once the great square tower of their

abbey played the part of a fortress. It was, how. ever, finally stormed by

Evers in 1544 and the marks of its burning may yet be seen on the

blackened walls.

Below, in the transept of the abbey, lies the sculptured tomb of the

last Marquis of Lothian—a bearded Apollo carved in stone; and at its

foot stands a Runic slab which may have lain upon the tomb of the Marquis’s

Druid forefathers. For there is reason to believe that the Cars, or Kers,

though their name appears on the Norman Roll of Battle Abbey, may count

back beyond Norman and Saxon invasions, to a Cymric ancestry. From the

tower top of the abbey can be seen, two miles away on the woody edge of

the Jed valley, the castle of Fernihirst,

feudal home of the family, who were staunch allies long ago of the

burghers of the town. Many a signal passed in bygone days between the

feudal castle and the abbey tower, when the significant gleam of helm and

spear was seen in the glades of the forest around.

The high banks of the Jed on the way to Fernihirst look their richest

when tapestried with the reds and browns and dark greens of their autumn

foliage. Doves, white and grey, wheel about them; and in the redstone

cliffs which here and there show themselves are to be seen several caves

which were used, like those at Ancrum and in Roslin glen, for refuge in

Border warfare. Here in the narrow green meadow between road and river,

its huge branches propped from the ground, stands the famous Capon oak,

last remnant of the ancient Jed forest. The American visitor writes his

name on its gnarled bark to-day; but Alexander III. may have winded

his hunting-horn here before America was dreamed of, as the stag stood at

bay below these branches; and it is just possible that its seedling stem

shot up green leaves in the forest before Herod was Tetrarch of Galilee.

Above, against the sky, on the cliff edge hangs Lintalee with its

memories; and a second glance is not needed to show how well-chosen the

spot was for the purpose of its occupant. Here, under the open sky, after

burning his own castle about English ears, the Good Lord James certainly

had his preference, rather "to hear the lark sing than the mouse

squeak."

Scenes and associations like these seem to ask for, if they be not

enough to make, a poet; and it is no marvel to know that down the road

here to school in Jedburgh from Southdean Manse, six miles away, used to

trudge, nigh two hundred years ago, James Thomson, the boy who was

afterwards to immortalise the beauties of the valley in his poem of ‘Autumn.’

The scenery of the district, indeed, is to be traced constantly in Thomson’s

poetry, and once at least he refers to it directly. Describing Scotland,

he mentions—

Her forests huge,

Incult, robust, and tall, by Nature’s hand

Planted of old; her azure lakes between,

Poured out extensive, and of wat’ry wealth

Full; winding deep and green, her fertile vales,

With many a cool translucent, brimming flood

Washed lovely, from the Tweed, pure parent stream,

Whose pastoral banks first heard my Doric reed,

With sylvan Jed, thy tributary brook,

To where the north-inflated tempest foams.

Grey among the woods on the right bank towers the donjon of Fernihirst,

and probably it would be impossible to find a more typical example of a

Borderer’s stronghold and its history. Above the iron-studded door in

the deserted courtyard is still to be traced in worn stone the escutcheon

of the place’s masters. Often has that courtyard rung with the hoofs of

hostile steeds, and the stone door-lintels echoed to the swinging

battle-axe. For they were a stormy race, these Kers, and the castle was

constantly the scene of attack and reprisal. Hither came home the jolly

baron, driving the beeves from Northumberland to be roasted whole in his

huge fireplace, the width of the vaulted kitchen. And hither, when the

captives were groaning in these grim dungeons, and while in the

"halls of grey renown" the revel and rude cheer were at their

height, came thundering at the gate the furious owners of the beeves.

Cracked crowns unnumbered were got here, and the red blood spirted

joyously over many a shirt of mail. High overhead, where the sun strikes

the tower, the blood - red spray of Virginia creeper clinging to the

parapet might well be the stain of the costly torrent which more than once

poured down these walls. Many a life it cost Lord Dacre, when, from the

burning of Jedburgh, he rode out to take the place in September, 1523. On

that occasion, even after the castle was taken, the Borderers managed to

cut loose every horse the victors had, to the number of fifteen hundred—women

and men alike seizing them and galloping off to the north. Six years

later, the Lord of Fernihirst was one of those imprisoned by way of

precaution when James V. rode out to "lay" the Border. Here, in

1549, D’Essé, the French general, took dire vengeance on an alien

garrison for their dark deeds among the defenceless women of the

countryside.’ And Ker of Fernihirst appears a few years afterwards as

one of the most gallant defenders of Queen Mary. Doubtless more than once

was Mary herself entertained within these walls.

Not only in feudal times, however, but in all ages has this Borderland

been deluged with blood. Only a mile and a half to the east of Fernihirst,

at Scraesburgh, lie the traces of a Saxon camp, made probably when that

nation came to fight the British Arthur; while the remains of a Roman

encampment — another northward-looking eyrie of these old-time eagles of

the south—are to be seen at Monklaw, the end of the hill-crest between

Teviot and Jed. Every foot of the ground, indeed, recalls some memory of

its own. Here the chant of the Runic priests has been silenced by the

trampling of the. Roman legions. Here, half-mystical amid the dimness of

the early centuries, has ridden the glittering Arthurian chivalry,

retreating by degrees before the north - rolling waves of Saxon and Viking

arms. Here, far - seen by night across the Border, have blazed the lurid

watch fires of the Douglas—warding for his master the gate of the

Scottish kingdom. And here, spurred southward on romantic quest, has sped

the fleet white palfrey of a fair, fate-followed Queen. The wanderer

to-day in the little valley of the Jed may find, at any rate, suggestions

enough of the storied past to occupy his thoughts during the quiet hours

of a summer afternoon.

|