|

Every

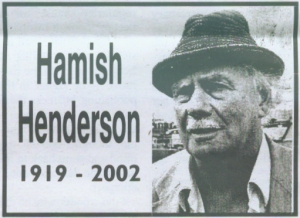

mention of Hamish Henderson since his death on the 8th of March has been

prefaced or followed by an anecdote. There is no doubt that he was, if

not larger than life, then at least radically different from most of the

people one has ever met. He wore his convictions, his passions and his

appetites on the outside of his large, gangling frame and that meant

that from him one got the direct experience of great vision and great

humanity. Every

mention of Hamish Henderson since his death on the 8th of March has been

prefaced or followed by an anecdote. There is no doubt that he was, if

not larger than life, then at least radically different from most of the

people one has ever met. He wore his convictions, his passions and his

appetites on the outside of his large, gangling frame and that meant

that from him one got the direct experience of great vision and great

humanity.

In 1990 he was invited to

speak at the Celtic Film and Television Festival at Douarnanez in

Brittany. The Festival that year was secured on the promise of a new

hotel which would be open just in time to take the two hundred or so

delegates from Scotland, Ireland and Wales but— as is the way with such

promises — the hotel failed to materialise and we all found

ourselves in a ramshackle, elderly building on the sea front at Treboul.

Its last full booking had presumably been during the Second World War,

when it housed German officers and its unsuitability for guests in March

was demonstrated by the fact that most of the rooms were built on a

beach, the damp from which pervaded every inch of the threadbare

furnishings.

The rooms and the hotel proper

were linked a boardwalk, and it was on that boardwalk late one night

that I found Hamish, slumped against a sand-dune. I brushed him down and

took him back to the bar for another drink, only to be turned on when I

mildly suggested that "The Freedom Come All Ye" was the only song that

was worthy to be a national anthem for an independent Scotland. Hamish

hated the idea of any national songs and said so in firm tones, and at

great length.

Hamish’s presence at the Festival

was a longer-term commitment

than any of us envisaged. Engaged for one lecture on a Tuesday he was

scheduled to fly in on the Monday and out on the Thursday, the direct

plane to Rennes only operating twice a week.

When I left on the Friday

he was still there, and indeed was apparently still there the following

Friday having missed the weather window three times. No doubt they are

still talking about him in the surrounding Breton fishing villages.

They are talking about

him elsewhere too. He touched so many lives that it is hard to find

anyone in Scotland above forty, who cannot regale you with his or her

one personal experience of Hamish, drunk or sober.

He was a fixture around

Edinburgh when I was a student of Scottish History and Scottish

Literature in the early 1970s and. he had a reputation not just for

extraordinary scholarship, but particularly for his strong and constant

advocacy of those who could not

speak for themselves, or who could not be heard in the clamour of the

capitalist twentieth century. But because he was

first and foremost a poet he did not just

agitate and campaign — he thought and felt, and one always got the sense

that the rawness of his feelings for suffering man and woman kind were

what drove him on.

There are still elitist enclaves

where the study of folk song and folk tradition are regarded as minor

disciplines. Hamish was the greatest of a generation who proved them

wrong and whose interest in travelling people, working people and people

from the linguistic and cultural minorities of Scotland led to a huge

body of recorded work and a huge development in understanding of our

mongrel nation and its cultures. Scotland is literally a different place

as a result of his endeavours.

But

like all cultural nationalists — in the best

sense of the words — he was also an internationalist. Indeed the two

stances are indivisible, for they both arise from a curiosity about, and

identification with, the question of our humanity and our relationships

one with another. It was, after all, Hamish who wrote those haunting

words of unity and compassion at the very start of his "Eleges for the

Dead in Cyrenaica" —"There are many dead in the brutish desert"

and who followed them later with the equally haunting "There were no

gods and precious few heroes/What they regretted when they died had

nothing to do with race and leader".

With all his other achievements and his more

accessible writings — particularly "The Freedom" and "The John MacLean

March" — it has sometimes been

possible to forget those early

poems and their great impact. Writing about

the poems of this former soldier, reflecting upon his experience and its

place in a suffering world, the Times Literary Supplement in January

1949 noted that

"Mr Henderson ‘s compassion

....

gives his poetry a rough humanity, a

sincerity and emotional truth that make it valuable".

Compassion, rough

humanity, sincerity and emotional truth were words that defined Hamish's

whole life. Scotland still has need of them.

Michael Russell MSP |