PREFACE

There are few subjects of greater value, or of more

interest to the diligent inquirer into the early history of our

country, than that of Seals This, indeed, is readily admitted by all

who have paid the least attention to the subject; while the best

historical works afford evidence that Seals form no unimportant

element in archaeological research. The importance of the subject

being so generally acknowledged, renders it unnecessary to offer any

lengthened introductory remarks with a view to direct attention to

the following pages.

It is hoped, however, that the following brief

remarks illustrating the art may not he considered impertinent or

out of place, and though they may contain nothing worthy the

attention of such persons whose opportunities of acquiring knowledge

have been more favourable than those of the writer, they may yet be

read with interest by others who have not paid much attention to it,

and may also prove interesting as being the result of the writer’s

own observations on a subject, the proper treatment of which

requires far higher qualifications than he can pretend to claim.

The art of engraving Gems or Seals is one that claims

the highest antiquity; and there is abundant evidence that it was

known and practised by nations long previous to the period of which

we have now any written records. Not only do the numerous gems of

the most remote antiquity found in India and Egypt prove this, but

we have the unshaken authority of the Holy Scriptures, an authority

which it is delightful to see is being-strengthened daily, by the

discoveries made by the intelligent and persevering Layard, of races

and nations whose very existence and names had wellnigh been

forgotten.

It is unnecessary to dwell longer on the art as

practised in India and Egypt, than merely to observe that it was

evidently held in esteem and importance by the natives of those

countries, and arrived at the same degree of perfection with the

sister arts of sculpture, painting, and architecture, which, judged

by the standard of excellence of modern times, may perhaps be

thought defective, yet in their kind were certainly excellent.

It was in Greece, in common with all that was

beautiful in art, that Gem or Seal engraving attained its highest

perfection ; but as the Roman power extended its possessions and

influence, the practice of the art was transferred from Greece to

the West, and under the Empire we find many works produced equalling

in excellence those of the Greek artists. With the decline and fall

of the Empire the art suffered also, and though never lost, it

lingered on almost in barbarity, till in the general revival of

letters and art under the magnificent family of the De Medici, it

again rose to perfection, and many works were produced that will

bear an honourable comparison with the ancient Masters. These

remarks, though perhaps not bearing directly on the particular kind

of Seals described in this work, may yet not be unnecessary as

pointing out the source, and tracing the progress of the art to the

period embraced in it.

It is yet undecided at what period the engraving of

Metal Seals, to which we are now to confine our attention, was

invented, or rather when they became more generally adopted, since

it cannot be doubted that the ancients were acquainted with the art

of engraving on metals; the beautiful coins, both of Greece and

Rome, are sufficient evidences of the fact, but it does not appear

that they extended the practice of it beyond engraving the die for

striking the coin. It seems most probable that the application and

extension of the art to Metal Seals may date from a period

subsequent to the fall of the Roman Empire, and in the rising

kingdom of the Franks ; or it may, as some believe, have arisen at

Constantinople, and thence been early adopted by the Franks; but at

whatever period or place such Seals may have become generally

adopted, there can be no doubt that from the sixth, and during the

following centuries, their use became very extensively spread

through the continental kingdoms of the north, and, doubtless, the

adjacent islands adopted the art and use of Seals not very long

thereafter. Leaving untouched the question regarding the use of

Seals by the Saxons, we will now confine our remarks to the Seals

immediately connected with Scotland.

The earliest Seal of that country yet met with, is of

Duncan II., in the latter part of the eleventh century. The twelfth

furnishes us with many interesting specimens both of the

Ecclesiastical Seals and of those of the Nobility and Gentry; and

though those of the earlier period may seem rudely executed, yet we

feel assured, that could perfect impressions of them be obtained,

they would be found not deficient in a certain degree of merit and

proficiency, sufficient at least to prove that the Art must have

been practised a long time previous to that of which we have now any

examples. From the time of Duncan, a.d. 1094, we have an

uninterrupted succession of the Great Seals of the Kingdom, all

executed in a manner that shows the excellence to which the art had

arrived at the respective periods; and, perhaps, on these Seals may

be best observed the progressive changes in the armour of the

Knight. In the earlier ones are specimens of the Flat-Ring,

Trellised or Maseled, and Chain Mail, which are gradually superseded

by Plate till the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, when the whole

defensive armour is of Plate, with its numerous additions fabricated

in the most elegant and costly style. (See Nos. 1, 3, 11, 13, 19,

27, 33, 39, 67, 72.)

The Seals of the Nobility and others of the twelfth

and thirteenth centuries, also afford interesting specimens of the

different kinds of armour; but it is not thought necessary to make

particular reference to the numbers where they occur.

During the thirteenth century, the Seals become more

numerous and of a greatly improved style. The Great Seal of

Alexander III., (Nos. 13, 14,) and those of the Ecclesiastics and

Nobles of the same period, are exceedingly beautiful, and executed

with a taste and truth of detail that would do no discredit to

modern art. This century also furnishes many and valuable

illustrations of the practice and definitive principles of heraldry.

The devices upon the Seals of the preceding century, though they

cannot he considered as heraldic, certainly contained the elements

of the science; thus the fleur-de-lis ou the Seal of John

Montgomerie, (No. 590,) afterwards became, with two additional ones,

the proper heraldic bearing of the family, and has so continued to

adorn their escutcheon unchanged for nearly eight centuries. Other

instances will he found in the following Catalogue that will readily

suggest themselves to the observant reader.

During the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the

art continued to maintain its excellence, which is particularly

apparent in the Seals of the Douglasses, the Lindsays, and other

magnates of the country; but towards the latter part of the

fifteenth century, the art began to decline, and during the

following one, few appear that can he compared as works of art with

those of an earlier time.

The Ecclesiastical Seals of the thirteenth and two

following centuries, afford most interesting specimens of the

costume of the different orders in the Church. The Bishops are

exhibited as vested in the chasuble, amice, alh, stole, maniple; and

the pall seems represented on one, (No. 856, and perhaps also on No.

939,) though not an Archbishop, yet perhaps as Primate of Scotland.

On the Monastic Seals also, or indeed wherever a figure of an Abbot

or Priest appears, may be observed the same propriety of costume.

(See Nos. 863, 903, 939, 942, 946, 94S, 969, 1005, 1006, 1067.)

About the latter end of the fourteenth century, the

design of the Episcopal Seals was changed by substituting for the

simple figure of the Bishop, which had hitherto been the usual

design, either a representation of the Trinity, the Virgin, or the

patron saint, within a niche or beneath a canopy.

The rich architectural design of these Seals cannot

fail to excite attention as valuable illustrations of the art.

Indeed from these Seals alone, might be almost distinctly traced the

rise, progress, and decline of that beautiful style of architecture

which prevailed during that period. Very instructive examples of

this may be seen in Nos. 870, S72, 877.

But the chief value of such a collection as the

following pages describe, will of course be found to consist in the

many important illustrations it affords of heraldry, of which, in

frequent instances, it may be said to be the earliest, if not the

only authentic record.

"When it is considered that very few and scanty

heraldic records of any kind are preserved in this country, and

those only of a very late period, Sir David Lindsay’s work in 1542,

being, it is believed, the earliest of the kind extant, it becomes

obvious that such a record of arms as the present work must be of

great value.

It. wouid far exceed the proper limits of these

remarks, to point out the numerous instances which might materially

assist in correcting many mis-statements and erroneous blazon, which

either through ignorance or inadvertency, have found a place in

several valuable works on Heraldry. One or two instances only will

be referred to as an evidence of the utility of the present work.

Sir James Balfour and other authors have stated, that the Merchiston

family of Napier assumed their arms upon the marriage of John Napier

with Elizabeth Menteith, the heiress of Rusky, and co-heiress of

Lennox, after the year 1455. The Seal, No. 621, a.d. 1453, is

sufficient proof that the Napier family carried those arms previous

to the marriage.

The same respectable authorities also state, that the

old Earls of Lennox bore a saltire engrailed cantoned with four

roses. In this collection are four (Nos. 489, 491, 492, 493) most

interesting and perfect Seals of this noble family, and in all of

them the saltire is carried without any engrailing. Neither is it

carried engrailed by the Stuarts, when they succeeded to the title

of Earl of Lennox, until about 1576. (See No. S04.)

The well known crest of the noble house of Hamilton,

which commemorates' a very doubtful tradition, will be found to be

very different from the crest on the Seal used by the chief of that

family in a.d. 1388, and who, moreover, was the first of the chief

line that assumed the name, (No. 400 ;) though it should be observed

the Earl of Arran in a.d. 1549, (No. 404,) carried the present

crest.

Mistakes have also been made by modern heralds in the

supporters.

Thus they have made the supporters of the arms of

Maxwell of Polloe, two monkeys, while upon the Seal No. 574, a.d. 1400,

they are undoubtedly lions ; and with great propriety the present

Baronet has dismissed the monkeys, and resumed the noble animals

adopted by his ancestors. These are only a few Instances of the use

of ancient Seals, many others will be found by the careful observer.

The custom of placing the crest above the shield,

seems to have been introduced about the middle of the fourteenth

century. The earliest instance in this Collection is No. 237, a.d. 135G,

a period rather earlier than that when it is supposed the same

custom was first introduced into England. Supporters seem also to

have been introduced about this period, and the same Seal, No. 237,

which gives the date of the one custom, supplies us also with the

date of the other. There are certainly earlier instances where the

shield is placed on the breast of an eagle, or where lizards and

other animals are placed at the sides and top of the shield, (See

Nos. 375, 7S5 ;) and there is the well known Seal of Muriel of

Stratherne, (No. 764,) cited by some writers as an example of an

early supporter; but none of them can properly be considered such,

being introduced merely to fill up the vacant spaces of the Seal,

from which practice, indeed, some have stated supporters to derive

their origin.

The Privy Seal of James I., a.d. 1429, (No. 43,) is

the earliest instance of the National Arms having supporters, and

these it will be seen are lions ; the unicorns do not make their

appearance before the reign of Mary, whose Great Seal, No. 59, first

brings us acquainted with them.

The examples of composed arms, (Nos. 768 and 1241,)

are interesting illustrations of the practice before the present

system of marshalling was adopted. Nos. 205 and 231 are the earliest

examples of impaling ; and No. 496 gives the first and finest

example of quartered arms, A.D. 1367.

Though well known to all acquainted with heraldry, it

may be necessary to mention that the useful system of indicating

colour by certain lines and marks was not adopted till a late period; any attempt, therefore, to give the proper tinctures of the arms

blazoned in this work could only have been made on conjectural or

doubtful authority ; it was therefore considered better not to give

any tincture, even in comparatively modern and well-known instances.

A few remarks may here be offered on the shape of the

shield, which has varied considerably at different periods. In the

earliest will be found the narrow kite-shaped shield of the Normans,

which prevailed with some modification, tending rather to the

pear-shape, till about the middle of the thirteenth century, when

the shield very generally became of that elegant form known by the

name heater-shape, a form well adapted for displaying with grace and

distinctness—a most essential matter in heraldry— the charges which

the science, then becoming practised on more definite principles,

rendered necessary. This shape continued to prevail during the two

following centuries, with some variations however having a tendency

to increase its breadth rather disproportionally. During the

sixteenth century, in common with all that was elegant in the arts,

the shield suffered many changes of form by no means adding to its

beauty or usefulness. The most fantastic and ill-conceived forms

were used, many such will be found in this Collection, though

special reference to them has not been made in the description.

The lozenge-shape, perhaps the worst that could be

conceived for the purpose of displaying armorial charges, has been

imperatively assigned as the only proper shape which ladies should

carry; but it seems remarkable that in the long period embraced in

this Collection, including the best periods of heraldry, in which

occur numerous instances of arms carried by females, but in no one

instance docs the shield take any other form than the prevailing one

of the period. In England, as early as the fourteenth century, the

lozenge-shape appears to have been used by ladies, (perhaps

exclusively in their widowhood,) but it certainly is singular that

no instance of that shape has been met with here until a very recent

period, and, considering how very unsuitable such a shape is for the

purpose, perhaps the sooner it is discontinued the better. Equally

unsuitable is the absurd fashion which has too extensively prevailed

in modern times, of having angular projecting points at the upper

part; it is, however, pleasing to observe at the present time a

return to the elegant form of earlier ages.

The subject of the mottoes and devices cannot be

passed unnoticed. Tt is of considerable interest, well deserving the

attention of the archaeologist, for as such Seals were probably

intended not for official or public purposes, but for private and

confidential intercourse, they become valuable and interesting

evidences of individual taste, or of the feelings or sentiments

prevalent at the time. Thus, the very early seal of Thor Longus,

(eleventh century, of which unfortunately there is no impression in

this Collection,) having the motto, “thor me mittit amico,” and the

Seals of the Dunbars, (Nos. 287-293,) are pretty examples of

individual friendly intercourse, and even the more tender sentiment

is observable on those of the latter. The very pretty Seal of

Alexander Til., (No. 15.) “ esto prudens ut serpens et simplex sicut

columba,” may well indicate the prudent policy of that able monarch.

The mottoes on the Ecclesiastical Seals (in which

class they are found more numerous) are, as might be expected, of a

devotional character ; and though, in some instances, they may

perhaps be adverse to the feeling of the present age, there are few

which, if considered rightly, would not afford instruction and

delight; certainly they are all expressive of a deep devotional

feeling that demands respect.

In some instances but little attention seems to have

been paid in adapting the motto to the device. It would seem as if

an antique gem were almost capriciously taken, and a motto engraved

around, not having the least apparent connexion or reference to the

device; hence some strange discrepancies arise. We have lately seen

one of this description from a collection in England, which has the

design of a young faun attending with the wine-cup upon Bacchus, and

the motto surrounding it is “jesps est amor h,” (Jesus is my love.)

In other instances the device and motto is most appropriate, and

produce a pleasing and striking effect. The Seal of Brian Fitzalan,

(No. 336,) is of this description. Also one from the collection of

Albert Wav, Esq., deserves particular mention :—a figure of a priest

consecrating the chalice, of course to be understood as emblematic

of that Divine work of love by which alone eternal peace can be

obtained, and the motto. “crede jiichi et est satis,” (Believe in

me, and it is sufficient.)

These examples are sufficient to show that mottoes

were generally in use from the earliest period ; but mottoes as

forming part of the accessories of arms are supposed not to have a

very early origin ; very few such occur in this collection, and

those not earlier than the sixteenth century. The Seal of Margaret,

Queen of James IV., a.d. 1526, (No. 55,) has the motto on a scroll

beneath the shield ; and the Great Seal of Queen Mary, No. 59, is

the first of that kind which has on it a motto instead of merely the

name and style. Yet it cannot be doubted that mottoes were used (as

part of accessories) at a much earlier period, and there is

certainly one, though it has not been read, on the Seal of Archibald

Douglas, Lord of Galloway, as early as a.d. 1373, (No. 23.9.)

It may well be feared that these remarks are

extending to an unreasonable length ; yet it is hoped the indulgence

of the reader will be granted while a few words on the material of

the Seal, the shape, and the method of cutting it, &c., will bring

this Address to a close.

The earliest mention of Seals in the Scriptures is

under the general term of signet or rings, which conveys no

information as to the material of which they were composed; but at a

later period where they are mentioned in connexion with the gems

adorning the breastplate of the High Priest, there appears pretty

certain evidence for believing that these signets or rings were

engraved gems set in gold or other metal.

There seems little doubt that the original matrices

of the Seals described in this work have been entirely formed of

metal. Of the few remaining specimens still preserved in the

cabinets of various collectors, they are for the most part formed of

brass, some are of silver, and one instance (No. 44) at least

supplies a fine specimen of a gold matrix. No matrices of a very

early date have been preserved, none indeed, it is believed,

previous to the fourteenth century, unless we except those

interesting gems in a metal setting which are met with about the

eleventh and twelfth centuries, of which it is believed there are

good specimens in Dublin. The occurrence of these gems on the Seals

of our early Barons is an interesting subject for inquiry. As they

are found pretty numerous on the Seals of the De Vescis and the

Avenels, we may suppose these warlike Knights to have been

collectors, and to have formed a cabinet during their crusading

expedition, of which perhaps it was the best fruits. They are

pleasing evidences of a desire for refinement which the possession

of such luxuries of art always inspire.

The Seals of the Nobility and Gentry present little

variation from the circular-shape; occasionally in the earlier

periods we find some of an oval, and more rarely the triangular or

same shape as the shield. On the other hand the Ecclesiastical class

presents little variation from that pointed oval-shape known as the Vesica

Piscis, and which seems to have been almost exclusively appropriated

to the Seals of Ecclesiastical persons and Institutions, at least

from the twelfth century.

This form is supposed to have some symbolical

signification, audit may not unnaturally be supposed to represent

the Church. For as the two circles, the intersection of which gives

this figure, may symbolically represent the circles of time and

eternity, so the figure given, may well represent the Church, where

in a peculiar manner are united the affairs of time with the more

important affairs of eternity; or in other words, the Church in the

faithful discharge of its duties, forms, as it were, a connecting

link or introductory passage,—a resting-place where, though within

the circle of time and still militant, may yet be met and enjoyed in

some slight degree the blessings of eternity.

The method of engraving or cutting these Seals was

entirely by the hand, with the aid of small chisels and suitable

punches of hardened steel, much in the same manner as the dies for

striking coins or medals are executed. The letters of the

inscription round the Seal, some of which are very beautiful, have

most probably been struck in from steel punches, but in the majority

of eases, they have evidently been cut with the hand.

The method of engraving gems or precious stones for

Seals is effected by quite a different mechanical process, being

accomplished by means of small tools of soft iron fixed in a lathe,

which is kept in motion by the foot of the engraver, in the same way

as the ordinary turning-lathe. The tool is kept moist with oil and

finely powdered diamond ; the stone to be engraved is then held and

guided by the hand against it, while the rapidly revolving motion of

the tool, aided by the diamond dust, cuts into the stone the desired

figure. By this simple process, and which has undergone no material

change from the earliest periods, have been executed the finest gems

of antiquity, which still command the admiration of the most refined

taste and judgment. Within the last few years, metal Seals have been

engraved by the same means as gems, only dispensing with the oil and

diamond dust, and using steel tools having serrated or file-like

edges. This method, however, is far from being generally practised,

though there is little doubt, when better known, it will be as

generally used for the engraving of Metals as of Stones. The greater

facility with which the rapidly revolving- tool is managed in the

hand of the artist, gives a decided advantage over the older and

ordinary method of cutting with chisels.

To complete these remarks, it seems necessary to

notice very briefly the wax of which these impressions were formed,

and the mode of appending them to the instrument. The wax has varied

much in colour during different ages, green, white, or the natural

colour of the wax, and red, have been used indiscriminately, without

being regulated by any particular rule, except, perhaps, the taste

of the owner or the fashion of the times. White, or the natural

colour of the wax, continued to be used for the Great Seals, and the

Burghs and Monasteries, at least for such as have a Counter Seal of

the same size ; but the green—in which colour they look exceedingly

beautiful— went out of use after the fourteenth century, and the red

predominated.

In the earliest periods the impressions have been

most carefully made, the wax being of one colour only, and without

leaving any border round the edge of the Seal; but at a later

period, it seems the impression was first taken in coloured, and

then imbedded in a mass of uncoloured wax, forming in some instances

a deep and broad border round the design. It is surprising how very

durable the wax has proved in many instances, preserving the

original sharpness and beauty of the impression almost perfect. In

the majority of cases, however, we have to lament not only the

ravages of time, but the still more fatal effects of carelessness.

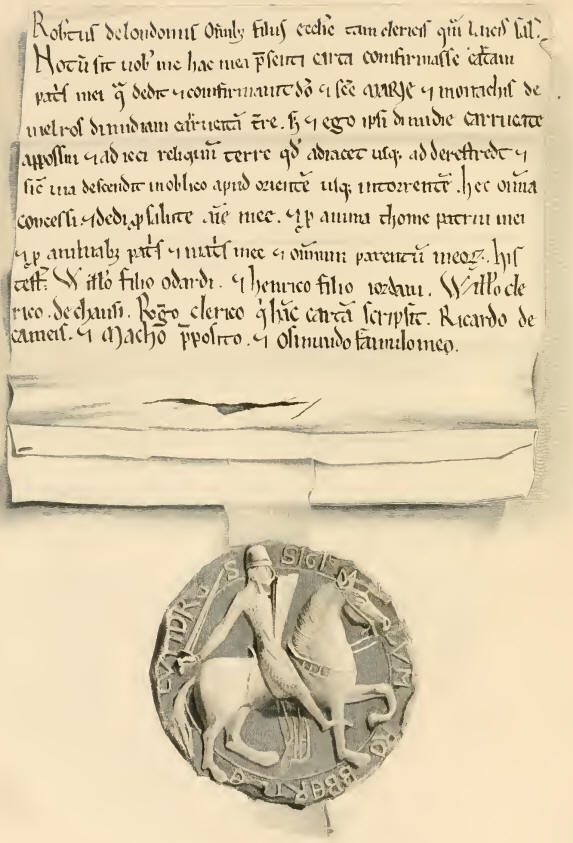

The manner in which these Seals were appended to the

document, was by passing a narrow strip of parchment, or a silk cord

plaited or twisted, through a slit in the parchment document at the

lower edge, and the ends being held together, the wax was pressed or

moulded round them a short distance from the ends, and the Seal

impressed on it, thus securely appending it to the document. In some

cases the wax was spread on the document itself, and the Seal

impressed. This however very rarely occurs, and in almost all in

this Collection the Seals are pendent.

That this was the practice in early periods even

among the Romans, some evidence is afforded by a passage in the

writings of the apostle Paul, where a figurative allusion is made to

a Seal having two distinct sentences, which we may suppose to have

been inscribed on each side of the Seal ; and if this be a correct

view of the apostle’s illustration, it furnishes evidence both of

the Seal being pendent and having a Counter Seal.

All the Seals described in this Catalogue have been

taken from original documents preserved either in public archives or

private collections, (a list of these will be found at page xxv.)

excepting those referred to as being at Durham. To the rich

collection there preserved the opportunity of gaining access has not

been afforded, and the few Seals in this Catalogue from that

collection, and one from the Duchy of Lancaster, are from casts

communicated by the Rev. J. II. Hughes, M.A.

It is believed that no work similar to the present

has yet appeared ; and if—though the result of many years’ labour—it

be not so complete as could be wished, it is hoped it will be found

to supply in some degree a want that has long been felt by the

zealous archaeologist. The hope is also cherished, that from the

publicity now given to the subject, and its great importance as

illustrating early history, greater facilities will be afforded for

increasing the collection, so that, eventually, Scotland may possess

a complete armory based exclusively upon Seals of an early date.

Such a work would do much to preserve heraldry in its legitimate

purity. There can be little doubt but abundance of rich materials

for such a work are in existence, and if the subject be viewed in

its proper light by our landed proprietors and chiefs of ancient

families, it is hoped that in that spirit of liberality which is

characteristic of the age, every facility will be afforded to

explore the hidden treasures of their charter-rooms, and bring to

light much that may benefit the public, and materially aid the

labours of the historian.

In conclusion, the writer of these remarks begs to

state, that he has taken every care to make the following work

accurate and interesting, but quite sensible of his many

disqualifications for the proper treatment of such a subject, he is

far from supposing it perfect, or that it will escape perhaps

merited censure ; he trusts, however, that no very serious errors

will be found. In works of this kind, produced even under the most

favourable circumstances, it is almost impossible to avoid mistakes;

he therefore craves some consideration. His labours are now

concluded, and he sincerely hopes that his humble efforts hitherto

made amid many disadvantages, but in the spirit of love for the

work, will be found worthy the patronage which has been bestowed ;

and should it be the means of leading any one better qualified than

himself to treat the subject in that large and comprehensive manner

it deserves, he will be much gratified at having been instrumental

in so doing.

It is now the pleasing duty of the writer gratefully

to acknowledge the favour and encouragement he has received from

numerous gentlemen, and the willing and efficient aid rendered to

the present work. To the Members of the lfannatyne flub in

particular he is much indebted, as without the assistance of that

honourable body it would have been impossible for him to have

produced the volume in the style in which it is now presented to the

Subscribers. His thanks are due to the authorities of the Register

House, for access to the valuable collection of charters contained

therein; to the Earl of Morton, the Marquess of Tweeddale, and other

proprietors, for the like favour; and in an especial manner is he

indebted to the following gentlemen, who have ever shown a lively

interest in the work, and have willingly contributed much valuable

information and assistance in forming this Collection:—Lord Lindsay

; Sir Walter Calverly Trevelyan, Bart.; P. Chalmers, Esq., of

Auldbar; Thomas Thomson, Esq., P.C.S.; Cosmo Innes, Esq.; W. B. D.

D. Turnbull, Esq.; Alexander Macdonald, Esq.; David Laing, Esq.;

Albert Way, Esq.; George Seton, Esq.; William Fraser, Esq.; and the

Rev. James Henry Hughes, M.A., late fellow of Magdalen College,

Oxford, Chaplain 1I.E.I.C.S., whose extensive knowledge of heraldry

and genealogy has proved a source of great assistance during the

period which his more important duties in a distant country allowed

him to remain in Edinburgh.

The name of the late George Smythe, Esq., younger of

Methven, should be included among those to whom the author is much

indebted for many valuable additions at an early period of the

formation of this Collection, and whose premature removal from a

sphere of usefulness is justly lamented by all who had the happiness

of knowing him.

To the liberality of C. K. Sharpe, Esq.; W. W. Hay

Newton, Esq.; and James Gibson Craig, Esq.; he is indebted for three

plates which illustrate the volume, in addition to those contributed

by the Bannatyne Club.

He has to acknowledge the kindness of Henry Drummond,

Esq., M.P., in permitting the use of some woodcuts which had been

engraved for illustrating his work of the “History of Noble British

Families.”

To Mark Napier, Esq., he is also indebted for the

woodcuts of the Seals of the Napiers.

To those gentlemen, and to all who have encouraged

the writer In the present undertaking, he returns his sincere

thanks, in the hope that the manner in which he has performed his

task will give satisfaction to those whose approbation he will

esteem as his best reward.

H. LAING.

Edinburgh, July 1850.

You can download

this book here

Additional Information

The following books provide

additional information on the Seals of Scotland

Supplemental

Descriptive Catalogue

History of Scottish Seals

from the eleventh to the seventeenth century, with upwards of two

hundred illustrations derived from the finest and most interesting

examples extant. By Walter de Gray Birch, LLD., F.S.A., Late of the

British Museum (1905) in 2 volumes.

Volume 1

| Volume 2

Scottish

Armorial Seals

By William Rae MacDonald, Carrick Pursuivant (1904)

Ancient Seals found at

Carrickfergus

Town Council

Seals of Scotland

You can view these down this page |