|

THE moralist who loved a good hater has surely no

right to complain of not attracting affection ; but I fear to shock many

excellent persons in professing that Dr. Johnson seems to me an overrated

personality. It is a commonplace that he shows much greater in Boswell

than in his own books; and to that infatuated worshipper we owe a rarely

intimate knowledge of one who appeals to John Bull as full of darling

national faults. No wonder that English writers should take a warm

interest in such a "character," and that Cockneys should crown him as

their king; but when one finds Scotsmen of insight, like Macaulay and

Carlyle, joining the chorus of veneration, one hesitates to put forward

one's own doubts to the contrary.

Still, at the risk of seeming to kick a dead lion,

let me say what an advocatus diaboli might bring against the canonisation

of Fleet Street's saint. For generations it has been dinned into our ears

that this man was wise, sturdy, manly, pious, and so forth, above his

fellows, while it is admitted that he was narrow-minded, ill-bred, full of

petty prejudices and credulities, much of a bully, as well as on occasion

a bit of a snob, as when he humbly deferred to the opinion of a Hanoverian

king, whose pension he had accepted after all he said on that subject. He

dealt much in moral maxims. So did Mr. Pecksniff. He was generous and

kindhearted to queer objects of charity let that stand to his credit. What

was his vaunted sense of religion but an erudite superstition, wide awake

to the "folly and meanness of all bigotry but his own," and not saving him

from craven dread of death? He had such a lazy conscience that only when

stung by Churchill's satire did he bring out the volumes on the

subscription for which he had been living for years. As to his love of

truth, even Boswell confesses the "robust sophistry" with which he would

argue for the sake of contradiction. As to his taste, let his criticisms

on Shakespeare and Milton speak. And why should we all be in a tale of

reverence for the wisdom whose deliverances have proved wrong on so many

points, notably in his opinion of Scotsmen. But for one Scot who was no

great honour to Scotland, this ponderous writer would surely have been

long ago "banished to that remote uncivil Pontus of the British poets,"

instead of being still welcome "within the cheery circle of the evening

lamp and fire."

Even if one be moved to belittle this literary

leviathan, one cannot but respect the courage that took him as an inactive

and infirm senior into those ill-known isles, where indeed he shows to

more advantage than on some other scenes of his life, the Jacobite

sentiments that were his leaven of romance seeming to soften down such

insolent contempt of outlandish starvelings as counts with your stout John

Bull for virtue. He visited the Hebrides at an interesting time, when

their old life was undergoing a rapid transition under new conditions, the

commercial order, as R. L. Stevenson says, "succeeding at a bound to an

age of war abroad and patriarchal communism at home." Some account of his

venturesome journey, then, may not be without interest for a generation

that does not much read that classical Journey to the Western Isles, nor

even Boswell's own account of his bear-show, which in truth is more

readable, none the less so for embalming some of the oracle's raciest

impromptus before they were cooked up into "Johnsonese."

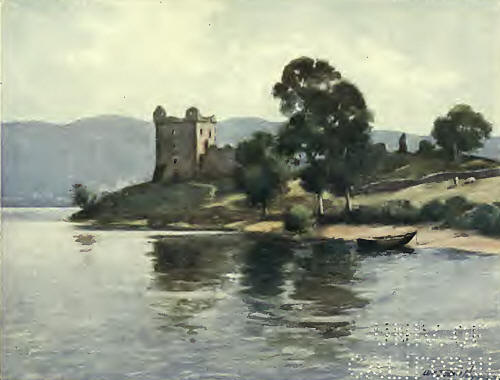

At Inverness the tourists took to horseback, with two

Highlanders running beside them to bring back the horses. They travelled

down the east side of Loch Ness to Fort - Augustus, beyond which they

found soldiers at work upon the new military road by which they struck

across the Rough Bounds into Glenmoriston, and thence by Glenshiel to

Glenelg. Neither Boswell nor Johnson has much to say of the

picturesqueness that moves their successors ; the devout biographer is

more concerned to record their fear of dirt and vermin, and the great

lexicographer emits such recondite observations as—" Mountainous countries

are not passed but with difficulty, not merely from the labour of

climbing, for to climb is not always necessary; but because that which is

not mountain is commonly bog, through which the way must be picked with

caution." After the ascent of one trying steep the sage was so cross that

his Highland attendant cried out to him, "See such pretty goats !" as to a

naughty child. This familiarity amazed Boswell, who found it quite natural

that his tired mentor should fly into a passion with him for riding on

ahead. When they reached the inn at Gleneig there was some excuse for

being sulky, since, a dirty fellow bouncing out of the bed where they were

to sleep, they chose to lie rather on hay, and got nothing to eat or drink

but a bottle of rum and some sugar, sent in by a gentleman as tribute to

the philosopher, who now behaved more philosophically, while it was the

turn of his famulus to be fretful. Had the tourist of to-day seen those

inns before they were turned into hotels, he might well bless the

road-makers of the Highlands. But in Glenmoriston our travellers had had

the luck to find an inn of which one room possessed a chimney and another

a small glass window. A generation later the Rev. James Hall has to tell

of one of the havens on this route, that after a hungry journey he

confined his refreshment to bottled porter, on observing the hands of both

mistress and maid.

The more luminous and voluminous Pennant, who had

preceded that pair of tourists in the Highlands by a couple of years,

exclaims over the fact that for two hundred miles along the west coast,

from Campbeltown to Thurso, there was nothing that could be called a town.

In Skye there were only one or two inns, and not one shop, according to

Johnson, who gives the population of the island at some 15,000. The

strangers had to depend on private hospitality ; and their first

experience was not cheering, as Sir Alexander Macdonald, who had come to a

small house on the shore to receive them, was liberal only in bagpipe

music. There were not even sugar-tongs on the table, Johnson noted with

disgust, where knives and forks had made their appearance not long before;

while indeed this fastidious citizen himself was in the way of eating fish

with his fingers, so that his convives might have felt some need for

sugar-tongs. But "Sir Sawney IS) " as he nicknames the parsimonious chief,

was the one house at which he complains of mean entertainment. Usually he

was treated like a lion, all the society of the district being gathered to

hear him roar; and for the nonce he proved so little pock-puddingish as to

enunciate "that which is not best may be yet very far from bad, and he

that shall complain of his fare in the Hebrides has improved his delicacy

more than his manhood." Boswell was satisfied with the respectful

recognition given to his great man; and it was only towards the end of

their trip that one ignorant laird asked if he belonged to the Johnsons

(i.e. the MacTans) of Glencoe or of Ardnamurchan. Both travellers were

edified by the books possessed by their hosts, who on the whole proved

more cultured than they had expected, though their expectations were not

pitched quite so low as that of an English tourist party stated, a

generation later, to have equipped themselves with beads, red cloth, and

such gewgaws for traffic with the naked islanders.

Skye was then mainly divided among three clans,

Macdonald, Macleod, and Mackinnon, whose hereditary feuds, at last kept

down by the arm of the law, began to be confused by the intrusion of

strangers. The clansmen, unplaided and disarmed, had turned their

claymores into such crooked spades as served them to dig up their rough

soil; and Boswell observed how their targets came in useful to cover

buttermilk barrels. The chiefs no longer went in semi-barbarous state with

a "tail" of swashbuckling henchmen, and had ceased to keep a petty court

of bards and sennachies, though a piper or two would not be wanting.

Deprived of their hereditary jurisdiction, as some of them were ready to

forget where the nearest magistrate might not be easily appealed to, they

still had such dignity and influence that it would be their own fault if

they did not attract the affectionate loyalty of which our travellers

record some notable signs. But this sentiment was being uprooted by a

disposition to raise the rents of their poor land, now commonly paid in

money instead of kind and service. A new spirit of calculation was abroad

since the days when faithful tenants had taxed themselves to pay double

dues, to the power in possession, and to the exiled lord. Johnson shrewdly

observed how the pastoral state began "to be a little variegated with

commerce," how this Arcadia had been "a muddy mixture of pride and

ignorance," and how the chiefs were disposed to take out in profit what

they lost in power, then "as they gradually degenerate from patriarchal

rulers to rapacious landlords, they will divest themselves of the little

that remains." Pennant, who takes more note of the misery and dejection of

the people, puts their numbers lower than Johnson, and states that the

rental of the island, 13500 in 1750, had in twenty years been doubled or

trebled on some farms.

The gentry of the island, lairds, "tacksmen," i.e.

the higher class of tenants, and ministers, lived with more or less show

of comfort in decent houses of two storeys, where, indeed, the parlours

had often to do double duty as bedrooms, and the floors were not always

clean or dry. The gentlemen, Johnson asserts, were inclined to the

Episcopal Church; but could not afford any services beyond those of the

parish ministers, who might have to preach in a room, at intervals of two

or three weeks, beside the ruined chapels "which now stand faithful

witnesses of the triumph of the Reformation." Of these pastors were "found

several with whom I could not converse, without wishing, as my respect

increased, that they had not been Presbyterians." He rather exaggerates in

giving them the credit of having exterminated the popular superstitions,

that would still take a good deal of extermination. He tells the story of

Maclean caning the people of Rum away from mass, a high-handed conversion

that in the neighbouring Catholic islands earned for Protestantism the

nickname "religion of the yellow stick." He shows how schools were at work

for enlightenment, where a century would yet pass before the three R's

came within reach of every bare- trotting Gael. In Skye he heard of two

grammar schools, at which boys boarded for three or four pounds a year,

but only during the summer months, "for in winter provision cannot be made

for any considerable number in one place."

Even in the better-class houses wheaten bread was

exceptional, oaten and barley cakes being the staff of life, with meat,

game, fish, cheese, and preparations of milk. The cottars' fare was

chiefly some kind of brose. Their poor crops went largely in making

whisky, like that "Talisker," now renowned, which is said to owe its

excellence to the water coming over some dozens of falls ; but an English

distillery has made in vain the expensive experiment of importing this

charmed water. Only in Iona did Johnson hear of beer being brewed. Though

every man took his "morning" as a matter of course, he did not see "much

intemperance," convivial gentlemen being perhaps a little shy before the

philosopher, who tasted whisky only once out of curiosity ("Let me know

what it is that makes a Scotchman happy!"); but he cared not to inquire as

to the process of distilling, "nor do I wish to improve the art of making

poison pleasant." He certainly saw one "drunken dog" in the person of

Boswell, who on a certain occasion sat up over a punch-bowl till 5 A.M.,

to be satirically rebuked by his monitor: "It is a poor thing for a fellow

to get drunk at night, and skulk to bed, and let his friends have no

sport." Boswell took special care to have this teetotaler provided with

water at dinner, who was also well supplied with his beloved tea, and with

the honey and preserves he admired on a northern breakfast table,

"polluted as it was with slices of strong cheese." The main deficiency was

in fruit and vegetables, chiefly represented by barley broth. Punch, made

for dinner and supper, which etymologically should have five ingredients,

here wanted one, for Sydney Smith was never so far from a lemon. "Under

such skies can be expected no great exuberance of vegetation," indeed, and

"few vows are made to Flora in the Hebrides." Some of the lairds were

trying to cultivate orchards about their houses. Others were zealously

introducing turnips and potatoes, that have made such a difference to the

Highlands but for years were banned by the stubborn conservatism of their

people, as in other parts of Europe. What late hay they gathered "by most

English farmers would be thrown away."

Their stock consisted chiefly of the small cattle, in

which a Highland maiden's dowry would formerly be paid, like the price of

a Kaffir bride. They had also ponies, an inferior breed of sheep, many

goats, with fowls and half-wild geese. The Highland prejudice against pigs

was still so strong that Johnson saw only one in the Hebrides; [It is a

question whether the Celtic aversion to pork had not its origin in some

such reverence as the cow bears among the Hindoos. The Gaelic for pig,

which to Saxon ears sounds so fitting, Muck, has honour in place- names,

as that of the great Ben Muich Dhu himself, not to speak of the "Boar" of

Badenoch, the "Sow" of Athole, and frequent names of lochs and islands. In

older days the Highlanders appear to have abstained from eating all fish ;

so at least some antiquaries assert.] and a like scunner, older than their

knowledge of the Bible, kept the people from eating hares, eels, and

scaleless fish such as turbot. Hares and rabbits had no chance against the

big foxes, on whose head was set a guinea blood-money. Rats and mice were

strangers to Skye, but the Hanover rat now began to invade some of the

islands. The place of these vermin was taken by weasels, which infested

even the houses.

In this land of "little sun and no shade," so deeply

fretted by inlets that no part of it lies more than a few miles from the

sea, where "every step is on rock or mire," Johnson missed villages and

enclosures. "The traveller," he laments to Mrs. Thrale, "wanders through a

naked desert, gratified sometimes, but rarely, with the sight of cows, and

now and then finds a heap of loose stones and turf in a cavity between

rocks, where a being born with all those powers which education expands,

and all those sensations which culture refines, is condemned to shelter

itself from the wind and rain." These "its" were often half starved, so

could not but excite a mixture of contempt and pity in the well-fed

English visitor. Pennant, with his practical eye, speaks of the people as

torpid from idleness, only bestirring themselves at the pinch of famine ;

but he does not want sympathy for them in the almost chronic famines due

to improvidence under a miserable climate, where hundreds "annually drag

through the season a wretched life; and numbers unknown, in all parts of

the western isles, fall beneath the pressure, some of hunger and some of

the putrid fever, the epidemic of the coasts, originating from unwholesome

food."

Leaving the comparatively green promontory of Sleat,

Johnson's party rode over moors and bogs to Corriechatachin, near

Broadford, where bad weather kept them a couple of days till Macleod of

Raasay sent his "carriage" for them, and as conductor a gentleman of the

clan who had done the same service to Prince Charlie in his wanderings.

The carriage turned out to be an open boat, in which four half-naked men,

chorusing Gaelic songs, rowed them through the Sound of Scalpa, and across

a rough open sea to the island of Raasay, Dr. Johnson sitting high on the

stern "like a magnificent Triton." In the new mansion-house, to which the

Laird had removed from his tumbledown castle, they found a whole troop of

Macleods, who every night danced and sang in honour of their guests; but

where they all slept was not so evident, some forty persons in eleven

rooms. Among the rest was the Macleod of Dunvegan, a young man fresh from

Oxford, who invited the strangers to his castle, for which they set out,

not without scruple, on a fine Sunday. Landed at the harbour of Portree,

then not even a village, where an emigrant ship was lying as hint of new

times for the Highlands, they went round by Kingsburgh, that Johnson might

have the satisfaction of making Flora Macdonald's acquaintance and of

occupying the very bed in which the Wanderer had slept ; but the royal

sheets had been devoted as shroud for the hostess. "These are not Whigs."

So little had they prospered on princely gratitude

that Flora and her husband were on the point of emigrating to America,

from which she eventually returned to be buried at Kilmuir in a grave left

for our time to honour. From the heroine's own mouth, with ekings-out of

other information, Boswell compiled an account of Charles Edward's escape,

which could now be safely published: even when she had been brought a

prisoner to London, the authorities seemed not very eager to convict a

fair traitor whose case excited much sympathy; and perhaps the prince owed

not more to her courage than to other half-loyal Macs who, in command of

the local militia, winked hard at the tricks of their kinsfolk, and did

not very keenly play the bloodhound upon the fugitive's doublings.

Macdonalds, Macleods, and Mackinnons all were willing to help him away,

though not many of them had turned out to take risks in his rash

enterprise; and the poorest cottar despised that price set on his head,

while one of the men who would not earn £30,000 by betraying him came

afterwards to be hanged for stealing a cow. The most zealous agents of the

Government in this matter seem to have been Presbyterian ministers, Lord

Macaulay's grandfather for one : this might be quoted as a case of

ascending heredity.

Dunvegan, to Boswell's delight, was a real old

castle, romantically placed on a rock, and his companion rejoiced to find

that its chatelaine, having lived in London, "knew all the arts of

southern elegance and all the modes of English economy." Pennant gives the

prosaic detail that there was a post-office here, in something like a

village, whence a packet sailed once a fortnight for the Long Island. "We

came in at the wrong end of the island!" Johnson exclaimed, in no hurry to

leave such good quarters. The old gentleman was suffering from a cold,

having "very strangely slept without a nightcap," but one of the ladies of

this hospitable family made him a large flannel one. As to that "strange"

habit of sleeping bare-headed but for a handkerchief, Boswell very

ingenuously owns that if his oracle had always worn a nightcap, and found

the Highlanders not doing so, "he would have wondered at their barbarity."

We may remember how in 1746 it was one of the royal fugitive's hardships

to part with his wig. Now the well- nightcapped Doctor settled down in

clover, dropping pearls of gruff wisdom eagerly picked up by Boswell, who

for his part chuckled to be the keeper of such a treasure, comparing

himself to "a dog who has got hold of a large piece of meat, and runs away

with it to a corner, where he may devour it in peace." But if he had no

longer to share Johnson's talk with the members of the Club, he had a

rival satellite in the Rev. Donald Macqueen, minister of Snizort, who

"adhered to" them on most of their journeys in Skye, and so well pleased

the great man as only now and then to get a taste of his rough tongue,

while his book duly compliments this gentleman on account "of our

intelligence facilitated and our conversation enlarged."

At Dunvegan they stayed a week, hearing the

traditions of the castle, and seeing its relics, for one that horn of

Rorie More, to hold two or three bottles of wine, which every Laird of

Macleod must drink at a draught in proof of his manhood; in our degenerate

age, it appears, this ceremony has to be performed by help of a false

bottom. No doubt they also saw, though neither of them mentions it,

another more lordly drinking-cup bearing the date 993, which seems to have

been a chalice; also the "fairy flag" of Dunvegan, a faded silk banner

from the East, probably a relic of crusading, which may be displayed

thrice and thrice only to save the house of Macleod from ruin— as it has

done twice, and may do once more. Though the young chief was deep in debt,

he let wine flow generously,—there being, indeed, no custom-house in

Skye,—" and venison came to the table every day in its various forms.

Boswell could hardly get his unwieldy companion moved

from this Capua ; but on September 21 they set out on their way back,

travelling from the west coast by Ullinish and Talisker, put up by one

Macleod or other as best he could ; and it made part of Highland

hospitality to convoy the guests on to their next shelter. At Talisker,

where their host was a colonel in the Dutch service, they met young

Maclean of Coll, who henceforth became their cicerone for the southern

isles. This promising laird Johnson compared to Peter the Great. He had

apprenticed himself to practical farming in England as a school of

improvement for the barren islands, on which he was the first to plant

turnips, an innovation pronounced by Highland wiseacres "the idle project

of an idle head, heated by English fancies." His father lived at Aberdeen

for education of the family, leaving such full power in the hands of the

son that he commonly bore the family title of "Coil," like the young

Lochiel and Glengarry of '45. To the veriest cit it is hardly needful to

explain that a northern laird was known by the name of his property, or a

farmer by that of his holding, where indeed certain surnames may be so

little distinguishing that in a hive of Campbells, Macleans, or what not,

one gets to speak of children as "Johnny Loch so-and-so" or "Jessie Glen

this-or-that."

With young Coil they now travelled back to Sleat,

looking out for a chance of leaving Skye, which would not present itself

every day in any lull of the equinoctial gales. By this time the townsmen,

who had expected to slip from island to island as easily as ordering a

postchaise, found it was more a question of going where and when they

could. Boswell began to fidget about getting back to Edinburgh in time for

the legal session, while Johnson in his whimsical moods now talked gaily

of fresh adventures, then again grumbled at not being safe and comfortable

on the mainland. At Armadale they were entertained more hospitably by his

factor than they had been on landing by the now absent Macdonald

chieftain, and the people appeared in no haste to get rid of that "honest

man" who had done them the honour of coming so far to lecture them. But

the wind suddenly changing, on the morning of Sunday, October 3, they were

hurried on board a vessel bound for Mull. Soon a storm came on; both the

unseasoned voyagers were sea-sick; Boswell was frightened to his prayers

neither of them had anything to eat; and after being tossed about all day,

even the skipper was glad to run before the wind for Coil, where they cast

anchor.

Safely landed, young Coll took them over the island

to his own house, a new one which was the best they had seen in the

Hebrides, but Johnson's humour was to belittle it as "a tradesman's box."

Not being occupied by the old laird, it was hardly in a state to entertain

distinguished guests, for whose entertainment Coll collected from his

kinsfolk such books as Lucas On Happiness, More's Dialogues, and Gregory's

Geometry, that might pass for light reading beside the pocket volume

Johnson had laid in at Inverness—Cocker's Arithmetic! —Boswell having then

equipped himself with Ovid's Epistles to "solace many a weary hour."

Johnson took interest in the traditions of the family, while his host was

forward to show him signs of nascent civilisation, about huts with gardens

gathered into a clachan. Coil had a shop and actually a mile of road, not

to speak of a school kept in summer by a young man who walked all the way

to Aberdeen for the university session. Here the visitors remained

imprisoned for a week, then moved down to the harbour to be ready for the

sailing of a Campbeltown kelp-ship on which they had engaged passage for

Mull. On the morning of the 14th the chance came by a fair breeze, and

with Coll in attendance they reached Tobermory at mid-day, just in time to

escape the daily gale that kept some dozen ships bound in this harbour.

At Tobermory they found rest in a "tolerable inn,"

from which Boswell hints how it was not easy to start his companion, while

Johnson admits that the eagerness to see Iona, as bouquet of their tour,

was mainly on Boswell's side. Taking horse, they rode through thick and

thin over the northern part of Mull, "a most dolorous country," where

Johnson lost the oak stick which he declared to be a valuable piece of

timber in such a wilderness. "Your country consists of two things, stone

and water. There is indeed a little earth above the stone in some places,

but a very little; and the stone is always appearing. It is like a man in

rags the naked skin is still peeping out." Such were the complimentary

jests by which Boswell reports him earning from the open-mouthed natives

so admiring epithets as "a hogshead of sense" and a "dungeon of wit,"

where indeed any kind of stranger would be as welcome as a peepshow, and

two learned gentlemen from London and Edinburgh made a whole circus.

At night the boat of an Irish vessel obligingly

ferried them across to put up with M'Quarrie, "chief of Ulva's isle,"

about to sell his possessions for debt and to enter the army at the age of

sixty-two, with forty years of life still before him. A Campbell, of

course, was the purchaser. Next day they went on by boat to Inch Kenneth,

where in dwindled state lived Sir Allan Maclean, head of another clan

whose star paled before the risen sun of the Campbells. On this island

Johnson's heart was cheered by the sight of a cart road, and Boswell's by

a parcel of the Caledonian Mercury, the first newspaper he had seen for

many a day. A little later, on the mainland, they found in a Glasgow paper

a report that Dr. Johnson was still kept in Skye by bad weather, on which

the paragrapher of the period smartly remarked—"Such a philosopher

detained on an almost barren island resembles a whale left upon the

strand." Could he have heard Goldsmith's happy hit at the stylist who

"would make little fishes talk like whales"?

After a day's rest, parting with Coil, they put

themselves in charge of his chief, who took them along the coast in an

open boat to Iona, till lately his own property, but now sold to the Duke

of Argyll. None the less was Maclean welcomed with humble affection by his

transferred clansmen, to one of whom, that had offended him by not sending

some rum, his bitterest reproach was, "I believe you are a Campbell!"

These men belonged to the generation over which their chief had once power

of life and death; and to Boswell the culprit protested, "Had he sent his

dog for the rum, I would have given it; I would cut my bones for him!" The

pilgrims from Fleet Street, who embraced each other on touching this

sacred shore, were in too exalted mood to grumble at having to sleep in a

barn. In the morning they examined the ruins that stirred Johnson's famous

paragraph—" Far be from me and from my friends such frigid philosophy as

may conduct us indifferent and unmoved over any ground which has been

dignified by wisdom, bravery, or virtue." At the time Boswell showed

himself the more deeply affected, who left his breakfast to return to the

cathedral for solitary meditation. "I hoped that, ever after having been

in this holy place, I should maintain an exemplary conduct." Johnson

mischievously writes to Mrs. Thrale how at Inch Kenneth his disciple had

stolen into the ruins there to pray, but was soon scared out by fear of

spectres.

Landed again in Mull, they travelled round its south

shore by Loch Buy, and on October 22 were ferried across to Oban. Next day

they rode on to Inveraray, in bad weather, which almost for the first time

moved Johnson to what our generation finds a becoming sentiment. "The wind

was low, the rain was heavy, and the whistling of the blast, the fall of

the shower, the rush of the cataracts, and the roar of the torrent, made a

nobler chorus of the rough music of nature than it had ever been my chance

to hear before." In ten miles they crossed fifty-five streams. He was

better pleased to come upon a good road that led them to an inn "not only

commodious but magnificent," at Inveraray, where "the difficulties of

peregrination were now at an end."

The distinguished chiels who had been taking such

notes spent nearly two months on a trip done by the live transatlantic

tourist in as many days. They had passed through and near some of the

scenic wonders of the kingdom, with as little notice as if these had been

Primrose Hill or Turnham Green. Wherever they stopped they made a point of

civilly visiting what ruins, antiquities, and such like were on show, but

it does not appear that they asked for beauty or sublimity, nor did their

guides suggest going out of the way for any prospect beyond that of a bed

and a dinner. Boswell wa, the less Cockneyish of the two, who could cry

out at sight of an "immense mountain" which Johnson scornfully put in its

place as an "immense protuberance"; and we know how he thought one green

field as like another as two straws. They did turn aside to see the Falls

of Foyers, as to Boswell seems not worth mentioning, while the rough

scramble made Johnson wish "that our curiosity might have been gratified

with less trouble and danger."

All travellers of that century, till Gray, were much

of the same mind. Pennant has small space to waste on Highland scenery,

though he so far comes under the genius loci as to put his very wide-awake

view of the people in the form of a fictitious dream. Burt frankly found

the mountains ugly, "most disagreeable when the heather is in bloom

"—prodigious! On Raasay Boswell was so frisky as to walk over the island

and dance at the top of Duncan, but he has not a word to say about the

view. For all their interest in Prince Charlie, nobody took the Fleet

Street gentlemen to see his cave near Portree; and but for passing by

Kingsburgh they left untouched the north-eastern peninsula of Trotternish,

tipped by the Macdonald castle of Duntulm and edged by the long line of

precipitous faces showing the giant's teeth of the Storr and such a

"nightmare of nature" as the Quiraing. The north-western headland,

Vaternish, they skirted to gain the Macleod castle, where Johnson "tasted

lotus" at the young chief's board, but was less concerned about the mighty

moor-mounds called "Macleod's Tables," and never heard of "Macleod's

Maidens," those graceful spires rising sheer out of the sea, nor of that

dizzy 'Waterstein cliff that faces the Atlantic near Dunvegan, and is

continued by precipitous walls down to Talisker. He could not help hearing

Rorie More's cascade, to which he one day took a toddle between the

showers; but neither the bear nor his monkey put himself much about unless

to look owlishly at some "Temple of Anaitis," or some cave recalling that

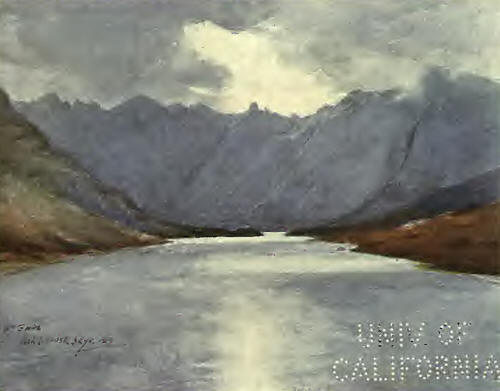

of Virgil's Sibyl. Boswell just mentions the Coolins, as reminding him of

Corsica, but nobody drew their attention to that wild sierra conspicuous

from nearly every part of Skye, an eerie chaos of wrinkled, rusted, ruined

tops that "resemble the other hills on the earth's surface as Hindoo

deities resemble human beings"; nobody told them of the black lochs and

gloomy corries hidden in those storm-breeding recesses nobody advised them

to make the rough tramp up Glen Sligachan or the perilous ascent of

Blaaven, or even to look at that highest point whose name titles it

Inachievable, as it is not to practised mountaineers of our own time. Two

well-to-do gentlemen had not come all the way from London and Edinburgh to

distress themselves by going near that "most savage scene of desolation in

Britain "—hardly accessible still unless through Loch Scavaig's brighter

anteroom, and then shunned by the Skyemen as goblin-haunted—the naked

hollow of Loch Coruisk, whose uncanny solitude a child then in the nursery

would bring to fame as a Highland Acheron:

Seems that primeval earthquake's sway

Hath rent a

strange and shatter'd way

Through the rude bosom of the hill,

And

that each naked precipice,

Sable ravine, and dark abyss,

Tells of

the outrage still.

The wildest glen, but this, can show

Some touch

of Nature's genial glow;

On high Benmore green mosses grow,

And

heath-bells bud in deep Glencoe,

And copse on Cruchan-Ben

But

here,—above, around, below,

On mountain or in glen,

Nor tree, nor

shrub, nor plant, nor flower,

Nor ought of vegetative power,

The

weary eye may ken.

For all is rocks at random thrown,

Black waves,

bare crags, and banks of stone,

As if were here denied

The summer

sun, the spring's sweet dew,

That clothe with many a varied hue

The

bleakest mountain-side.

In coasting Skye, not indeed along the finest

stretch, all our ponderous Rambler observed was how the crags made landing

difficult, especially for an enemy ; while Boswell cast a glance at "hills

and mountains in gradations of wildness." The latter, even when not

perturbed by a rough sea-passage, owns that he finds "a difficulty in

describing visible objects," such as those revealing themselves thus to a

ready writer of our time.

Here we beheld a sight which seemed the glorious

fabric of a vision :—a range of small heights sloping from the deep green

sea, every height crowned with a columnar cliff of basalt, and each rising

over each, higher and higher, till they ended in a cluster of towering

columns, minarets, and spires, over which hovered wreaths of delicate

mist, suffused with the pink light from the east. We were looking on the

spiral pillars of the Q uiraing. In a few minutes the vision had faded;

for the yacht was flying faster and faster, assisted a little too much by

a savage puff from off the Quiraing's great cliffs ; but other forms of

beauty arose before us as we went. The whole coast from Aird Point to

Portrec forms a panorama of cliff-scenery quite unmatched in Scotland.

Layers of limestone dip into the sea, which washes them into horizontal

forms, resembling gigantic slabs of white and grey masonry, rising

sometimes stair above stair, water-stained, and hung with many-coloured

weed; and on these slabs stand the dark cliffs and spiral columns:

towering into the air like the fretwork of some Gothic temple, roofless to

the sky; clustered sometimes together in black masses of eternal shadow;

torn open here and there to show glimpses of shining lawns sown in the

heart of the stone, or flashes of torrents rushing in silver veins through

the darkness; crowned in some places by a green patch, on which the goats

feed small as mice; and twisting frequently into towers of most

fantastical device, that lie dark and spectral against the grey background

of the air. To our left we could now behold the island of Rona, and the

northern end of Raasay. All our faculties, however, were soon engaged in

contemplating the Storr, the highest part of the northern ridge of Skye,

terminating in a mighty insulated rock or monolith which points solitary

to heaven, two thousand three hundred feet above the sea, while at its

base rock and crag have been torn into the wildest forms by the teeth of

earthquake, and a great torrent leaps foaming into the Sound. As we shot

past, a dense white vapour enveloped the lower part of the Storr, and

towers, pyramids, turrets, monoliths were shooting out above it like a

supernatural city in the clouds.

From writers like Robert Buchanan one might quote

dozens of such enthusiastic descriptions, showing how a later generation

has gone back closer to the bosom of Mother Nature than lay that age of

wigs and nightcaps. Yet it is those whose play rather than their work

takes them into the wilds who are most prone to such new enthusiasm. Now

that Skye is somewhat thinly dotted with birch and larch clumps and

gardens, and belted with a high-road winding round her deep inlets between

groups of houses where church, schoolhouse, and hotel have sprung up

beneath cairns and ruins, her inhabitants are rather apt to wonder why

strangers give themselves so much trouble in seeking out the most

forbidding wilds of their island, that excite their own feelings no more

than Cobbett admired Hindhead when he found the roads rough and the soil

not suitable for turnips. Those weird scenes which the well-fed Sassenach

seeks, as Buchanan says, to "galvanise" his soul with holiday emotion,

overshadow the cottar's daily life with poverty, hunger, and dread. Some

parts of Skye have now been made comparatively trim and tame, beside

others left hopelessly barren and dismal, with peat and rushes for their

best crop; but nowhere perhaps in Britain can one better learn how "nature

is not always gracious; that not always does she outstretch herself in

low-lying bounteous lands, over which sober sunsets redden and heavy-uddered

cattle low; but that she has fierce hysterical moods in which she congeals

into granite precipice and peak, and draws around herself and her

companions the winds that moan and bluster, veils of livid rain." This

poor "island of cloud" is indeed most rich in "frozen terror and

superstition" for those who have eyes to see.

Between contemporary pilgrims of the picturesque and

the dull observers of older days, came to Skye an invasion of geologists

and such like, who did much towards proclaiming its grand points. One of

the pioneers of scientific invasion was the Frenchman Faujas de St. Fond,

who does not shine in the orthography of Scottish names. But of these

explorers one need not speak here, unless to distinguish that humorous and

hard-headed savant MacCulloch, whose hammer was brought to bear on many

time-weathered sentiments. His Western Islands is more strictly

geological, but his Highlands and Western Isles is full of rollicking

pages, though stuffed rather too much with learned facetiousness, which

would have tickled Mr. Shandy, while it may prove hard reading "when, in

after ages, the youths of Polynesia shall be flogged into English and

Gaelic as we have been into Greek and Latin "a sentence that appears rough

sketch for a more celebrated Mac's New Zealander. Macaulay may also have

lifted the formula, "every schoolboy knows," from this author, who varies

that phrase by "the merest schoolboy" or "the minutest Grecian," and in

more boldly laying down "all the world knows what Callimachus says," will

not recommend himself to a generation better acquainted with Macaulay's

dicta and dogmata than with what song the Sirens sang, or what tartan

Achilles wore when he seems to have disguised himself in a kilt. Another

famous saying, that has become a cliché in our day, as to the South Sea

islanders' trade of taking in one another's washing, seems adumbrated by

MacCulloch's wonder how Highland shopkeepers contrive to keep open,

"unless they have agreed to live on gingerbread kings and carraway

comfits, and to buy all their pins and tape from each other." And for a

final sample of this author's shrewd wit, let us hear that "never have

books been so black, so thick, so large and so long, as when they have

been written about nothings." This warning spurs me on from digressions

that might be extended to a folio—

Heavy and thick as a wall of brick,

But not so

heavy and not so thick

As—

some volumes of travel one could mention.

One need not waste many words on the Cockney tourists

who get the length of Skye to stare at the children's bare legs and to

sniff at the peat fires, such admiration as they are capable of being

directed by tourist tickets and guide-books. By Cockneyism I do not mean

citizenship of the world's greatest city; indeed it is not for me to file

the international nest that has grown so big round the sound of Bow Bells.

To be a right Cockney is to be impotent of any outlook but from our own

Charing Cross or other restricted observatory, in which moral sense we are

all by nature Cockneys, some more, some less. There are Cockneys of time

as well as of place. The eighteenth was very much of a Cockney century,

hoodwinked by its own wigs, nightcaps, pews, quartos, and other

indispensable institutions. The nineteenth century has taken pains to

foster a more catholic spirit ; but some of its sons are slow to learn how

poor is their little duck paddle or brackish lochan beside the ocean that

goes round the earth, itself a drop in that inconceivable immensity of

forces and phenomena against which the brightest human life flies out to

die like the tiniest peat spark.

To my mind some of the most offensive Cockneys are

those who never drop the Ii of" Hail Columbia!" I am not specially dotting

the i's of this remark for a certain couple that some years ago undertook

to make Johnson's tour on foot, then, finding the weather chill and wet,

came back to publish an ill-humoured and well-illustrated book that got

them into critical hot water. Still less need one have anything but a

thousand welcomes for the American travellers who are travellers indeed,

who look through glasses of knowledge and sympathy rather than through

prejudiced goggles dulling every prospect, seen as from the rush of a

motor-car. But there is a kind of U.S.A. bookmaker, who very much

"fancies" his acuteness, bounded on one side by the spelling-book and on

the other by the sensational newspaper ; and such a smart descendant of

ours has no shame in exposing his narrow-mindedness while exulting over

the nakedness of his grandfatherland. Boswell did not write himself down

an ass more plainly than some note-takers I could quote, whose standard of

measurement seems always the Capitol at Washington, the water tower of

Chicago, the Nob Hill of 'Frisco, or some other universal hub of their

self-satisfaction. What they always cry out upon is the poverty, the

shiftlessness, the backwardness of Highland homes, for which they go on to

blame the landlords as tyrants unscrupulous as Tammany bosses, or Western

evictors of Nez Percés Indians. Their pity for the poor does them credit;

but much of it is wasted by complacent philanthropists unable to conceive

how life may be worth living without ice-cream, elevators, political

"machines," hourly newspaper editions, endless Stock Exchange tapes, and

the like necessaries of high-toned civilisation. To this kind of

transatlantic tripper who comes hurriedly poking into lordly hail and

smoky hovel, peeping with such an uppish air on our manners and customs as

if we were Sandwich Islanders, one would say Proculeste profani! but of

course one might as well try to scare a yellow - press reporter with a

notice to trespassers. And when the like of him has published his hasty

impressions, these may make wholesome study for us as showing how our

ancient idols strike a stranger from some exceedingly "up to date"

standpoint.

To find the western islands described with insight

and sympathy one can go to the writers above quoted, and to Miss Gordon

Cumming's Hebrides, which I have not quoted on Skye, for fear of being

tempted to deck my grey page unduly in borrowed plumes as from some bird

of paradise. She was doubly a Highlander by blood, who could also inform

her survey with comparisons wide-drawn from other lands. Buchanan, I fear,

was born south of the Border, yet his forebears must have heard the slogan

of the wild Macfarlanes on Loch Lomond. As for Alexander Smith, unless

descended from some Highland Gow, such as that Hal who fought on the Inch

of Perth, he may frankly be set down for a Sassenach, a Kilmarnock body

"at that" but this poet's prose is thick set with Highlands of fancy; and

no book of the kind makes better reading than his Summer in Skye. All

these writers, by the way, have a good word for Dr. Johnson, who so

roughly abused their country; and when I consider how that worthy did

penance at Uttoxeter for a sin of his youth, I am half-minded to humble

myself on the cutty-stool as else unable to look up to one whom so many

better men have judged great and wise.

|