HIGHLANDS AND ISLANDS, as we Scots chuckle to

ourselves, is the one phrase which an Englishman cannot mispronounce. I

read lately a book of Scottish travel by an American, who made my

countrymen leave out their h's like any Cockney; then I at once laid

aside this writer's observations as vain. The humblest Scot never drops an

h, unless in words like hospital, which the Southron painfully aspirates

in his anxiety not to be judged vulgar, as in living memory he has tacked

this test of breeding on to humour and humble. More fairly we may be

charged with overdoing the i sound; and there are two or three words in

which we insert it: huz, for instance, said in some parts for "us." In the

game of "tig," anglicé "touch" or "tag," my childish conception of the

formula "who's hit?" made it a participle meaning "struck" or "touched,"

till I heard German children crying in like case "Ich bin es!" when I did

not know how hit is the old English pronoun, preserved by Scots dialects,

which are the truest copies of our national tongue.

Once, indeed—it was

in Derbyshire-1 came across a man speaking with a strong West Highland

accent, yet misusing the letter Ii. This seemed such a prodigy that I made

a point of getting it explained. It turned out he was the son of a

Yorkshire shepherd, who had taken service on the Isle of Mull. There the boy carne to

be most at home in Gaelic, while what English he had was on a bad model -

the reverse of lingua Toscana in bocca Romana. His younger brothers, he

told me, grew up hardly speaking English at all, and he, the bilingual

member of the family, had often to interpret between them and their

mother, who could never get her tongue round the strange speech. We speak

of a mother-tongue; but it is from their playfellows that active lads

seem to learn fastest. The Italian author De Amicis relates an experience

like that of this Yorkshire family: transplanted at the age of two from a

Genoese to a Piedmontese town, he picked up the Piedmontese dialect so

readily that his own mother could not always understand him when once he

got loose from her apron-strings.

In the far Highlands and Islands can

still be found countrymen of ours who speak no language but Gaelic, these

hardly, indeed, unless among older people, the rising generation being

schooled into the dominant tongue, in their case often a stiff book

English, spangled with Lowland idioms and native constructions. Distrust

the author who reports true Highlanders talking broad Scots after the

school of Stratford-atte-Bow. This remark does not fully apply to the

Central and Inner Highlands, where some generations have passed since

people living a mile off spoke tongues foreign to each other, as may still

happen on the borders of Wales. In the Highlands best known to tourists,

the blending of blood, language, and customs has gone so far that a

stranger may be excused for confounding a Perthshire strath with the true

kailyard scenery. Beyond the Great Glen, still more markedly beyond the

sounds, firths, and minches of the west coast, we find Highlanders less

touched by the spirit of a practical age, whose first breath sets them

shivering and drawing their tartans about them as they wake from fond

dreams of a romantic past. All Scotland, alas! has been too much overrun

by the alien clan of MacMillion, who, as one of its most eloquent sons

complains, go on cutting it up into "moors" and "forests," and its rivers

into "beats." Sheep-farming on a large scale and other industries have

here and there brought Saxon sojourners, like my Derbyshire acquaintance,

to the western wilds. The aristocracy are much Anglified, even in these

"Highlands of the Highlands." But the mass of their human life is still

Celtic, or at least Gaelic, if language can be trusted, with an old blend

of Teuton infused both by sea and land, through Norse, Norman, and Saxon

invaders, and with touches of Spanish Armada or other shipwrecked blood

surmisable here and there among waifs and strays all going to make up a

stock that may have absorbed who knows what prehistoric elements. The

controversy between Thwackum and Square is not more famous than that hot

debate between Mr. Jonathan Oldbuck and Sir Arthur Wardour, which stands

as warning to a modest writer not to quarrel with any readers, at least at

an early stage of his book, by taking sides on certain much-vexed

ethnological and philological questions.

To reach those rain-bitten and

wave-carved coasts where the true Highlander mainly holds his own, we have

various ways now made smooth by arts which go on sapping his seclusion. It

does not much matter which way the stranger takes, for he can hardly go

wrong, to understand how right Gray was when he told his mole-eyed

generation, "the Lowlands were worth seeing once, but the mountains are

ecstatic, and ought to be visited in pilgrimage once a year." All roads to

the Inner Highlands lead through the Outer Highlands, more fully described

in Bonnie Scotland.

For leisurely tourists the choice road is still by

water, down the Clyde from Glasgow. If the name of this river be derived,

as is said, from a Celtic word meaning clean, that title has become a

mockery, since its banks from Glasgow to Greenock sucked together the most

industrious life of Scotland. "Come, bright Improvement, on the Car of

Time!" sang Glasgow's youthful poet, but lived to exclaim against the

questionable shape in which came a spirit he had invoked so hopefully:

And call they this Improvement?—to have changed,

My native Clyde, thy

once romantic shore,

Where Nature's face is banished and estranged,

And Heaven reflected in thy wave no more;

Whose banks, that sweetened

May-day's breath before,

Lie sere and leafless now in summer's beam,

With sooty exhalations covered o'er;

And for the daisied

green-sward, down thy stream

Unsightly brick-lanes smoke, and clanking

engines gleam.

The banks of the Clyde have not grown more Arcadian since

Campbell's day, so the traveller does well to hurry by rail over the

windings of the smoky river, embarking at Greenock or Helensburgh, where

it broadens out into a firth deep enough to drown the offences of man.

Here launch forth a fleet of steamboats, whose admirals, almost alone in

Britain, rival the luxurious arks of the Hudson and the Mississippi; and

here begins a "delectable voyage," too often spoiled by rain, else warmly

praised by a hundred pens, for instance in Colonel Lockhart's Fair to See,

one of the most amusing of Highland novels, as readers might not guess

from this opening passage:

The mountain panorama which greets you as you

start, noble though it be, is but the noble promise of still better things

for it cannot show you the exquisite variety, the contrasts, the

combinations, the marvellous chiaroscuro, the subtle harmonies, the

sublime discords, that meet you and thrill you at every turn, passing

through the inner penetralia of all that is most glorious in the land of

mountain and of flood. Gliding through those strange sounds and estuaries,

with their infinite sinuosities, traced about peninsula and cape and

island—traced as it were with a design of delighting the eye with sudden

presentments of scenic surprises, as it were with a design of furnishing

not one, but twenty points of view, wherefrom to consider each salient

wonder and beauty round which they seem to conduct you proudly on their

glittering paths—there must be something far wrong with you if you find no

delight in all this. For here indeed you have a succession of the noblest

pictures,—no mere iteration of rugged mountains, monotonous in their grim

severity and sublime desolation,—no mere sleepy tracts of unbroken forest,

nor blank heaths losing themselves vaguely in the horizon, nor undulating

expanses of lawn-like pasture-land, but with something of all these

features blending in each of the splendid series; every feature in turn

claiming its predominance, when all the others seem to pose themselves

about the one central object, sinking for the moment their own

individualities that it may be glorified.

For the first stage of this

voyage, indeed, the shore is too much masked by a long line of bathing and

boating resorts, to which Glasgow folk love to escape even from the

comforts of the Saltmarket. On the right-hand side stands Dunoon, whose

fragment of ruined fortress looks stranded above a flood of hotels, shops,

and villas, in which several villages have run together into a town.

Farther down, on the Isle of Bute, Rothesay makes the focus of Clyde

pleasure trips, no mushroom resort, but seat of an ancient royal castle

that titled the heir of Scotland. The Stuarts still flourish here in the

person of the Marquis of Bute, who is as great a man in the Principality

of Wales as in the Dukedom of Rothesay. The old town has expanded into a

couple of miles of esplanade, curving below green hills upon a land-locked

bay, its surface lively with yachts, pleasure boats, and steamers that in

the summer season turn out myriads of excursionists to sack the joys of

the place. I was about to belittle Rothesay by calling it the Southend of

Glasgow; but in view of its hydros, its mineral spring, and its background

of dwarf Highland scenery, its character may better be expressed in terms

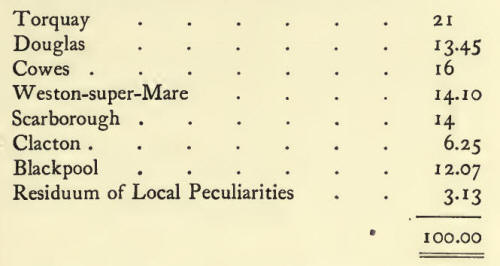

of chemical analysis:

In winter, when "Wee Macgreegors" and the like desert its waters, Rothesay

becomes the Ventnor of Scotland, recommended by a sheltered western

mildness, which indeed its own guide-book advocate has to qualify as

"rather humid." Even in ordinary winters it may bear comparison with South

Devon or the Isle of Wight, while sometimes a whim of Nature has set the

thermometer standing higher here than at Mentone. This mildness is

attested by exotic plants in Lord Bute's park, whose late owner,

Disraeli's "Lothair," for a time maintained colonies of kangaroos,

beavers, and other outlandish creatures. Whatever harsh things may be said

of Eastern Scotland's climate, the West Highland skies are more apt to be

"soft," and to snow only "whiles." Some patriotic Scots go so far as to

claim that their country is on the whole warmer than England, no part of

the former being over forty miles from the Gulf Stream that so muggily

wraps the islands of our far north.

For the rest, Bute makes a miniature

of the Highlands, once rich in chapels and hermitages, as in monuments of

a dimmer faith, too many of which have been destroyed, like that monastic

ruin carted away to baser uses by a thrifty farmer, who thought to gain

his lord's approval for "clearing" a beautiful spot. A modern memorial,

not to be pointed out to French visitors, is the woods of Southhall,

planted by a veteran owner as plan of the battle of Waterloo. The boss of

the island, Barone Hill, rises over Soo feet, from which, or from the park

above Rothesay, fond local eyes have tried to count a dozen counties, and

half a dozen are certainly in view. "Why don't you pretend to see to

America, while you are about it?" quoth a rude Southron to some local

prospect-monger; and the dry answer was, "Ye can see farther than that—as

far as the moon!"

Bute, of course, sinks to a mere Isle of Wight when

compared with the grandeurs and loveliness of Arran, lying to the south.

This island indeed has scenery which some declare unsurpassed in Britain,

notably on the flanks of its Goatfell summit. Yet while Glen Rosa, Glen

Sannox, and Loch Ranza have often been famed by painters, it seems the

case that poets, novelists, and other artists in words make not much copy

out of the charms of Arran. One feels inclined to suspect authors

Glen Rosa, Arran

of Sybarite tastes, since a weak point of Arran as

tourist ground is, or has been, a want of accommodation under the shadow

of a ducal house that looked askance on building. The only two towniets on

the island, Brodick and Lamlash, count their population in hundreds; and

their hotels are hard put to it to accommodate the strangers who have

often had to be content with a shakedown in the room used as an English

chapel, or with shelter in one of the few bathing machines; I have heard

of a whole boatful of excursionists lodged in a hay-field. Holiday

quarters in this paradise are engaged for a year ahead, and Piccadilly

prices may have to be paid as rent of a hovel. Thus hitherto Arran has

been preserved as a haunt of real nature-lovers, and within two or three

hours' sail of Glasgow one could find an almost pristine solitude of

purple heather and solemn crags all unprofaned by watering-place gaiety or

luxury. The sourest Radical of sound taste might here exclaim, "God bless

the Duke!"—not of Argyll —yet one wonders what a late duke's creditors

thought of such a demesne being kept clear from vulgar considerations of

profit.

I am not going to try my hand at word-pictures of these glorious

landscapes, for "how can a man can what he canna can?" as I once heard a

Highland lad sagaciously express himself in our foreign tongue. One had

better not invite one's readers even to land on Arran, lest there might be

a difficulty in getting them off again; but if they do, let them not omit

the ascent of Goatfell, no perilous adventure, for a view hardly surpassed

in Scotland, as shown in Black's Where shall we go? a work over which the

present author has some rights of plagiarism.

The summit is composed of

mighty rocks, ensconced among which one may shelter from the searching

wind and gaze in comfort at the wild picture around and below—Glen Rosa at

our feet, with its sharp precipices beyond rising into the pinnacled

heights of A Chir and Cir Vohr; the saddle into Glen Sannox (the glen

itself is invisible from here), and the equally sharp and even loftier

ridges beyond that glen ; the nearer range of Goatfell itself extending

round a nameless glen below us, and terminating in a sharp peak that

overhangs the village of Corrie; and beyond the limits of the island

itself and the broad belt of sea which allows the eye to range unchecked,

a glorious bewilderment of heights and hollows innumerable, with here the

smoke of a manufacturing town, and there the familiar shape of some

mainland mountain-giant, the view extending on a clear day, it is said,

from Ben Nevis to the Isle of Man.

Arran owes its unsophisticated state

also in part to lying a little off the highway of travel. Strong-

stomached voyagers may round the Mull of Cantyre, to be tossed upon

Atlantic waves, and thus get a chance of seeing Ailsa Craig, "Paddy's

Milestone," whose cliffs are in some respects finer than the much- visited

Staffa. The gentle tourist takes an easier and straighter line to Oban.

His boat threads the beautiful Kyles of Bute, then stands across to

Tarbert, on the Isthmus of Cantyre, from the farther side of which goes

the steamer to Islay. Up Loch Fyne is reached Ardrishaig, terminus of the

big ark whose Oban-bound passengers are transferred to a smaller craft for

the Crinan Canal cut, that brings them over to the island- studded and

cliff-cornered sounds of the west coast. Well then for the land-lubber

that he fares forward on one of Messrs. MacBrayne's stout craft! To play

the Viking here without experience were a perilous task, so thick-set are

these waters with rocks and shallows, so tormented by sudden shifty

squalls, so distracted by currents, eddies, and rushing tideways. But the

steamer pants masterfully through the Dorus Mor, keeps clear of the

Maelstrom of Corryvreckan, whose roar may be heard leagues off in calm

weather, and steers safe along the islands of the Firth of Lorne, past the

great slate quarries on Easdale, round the bridged island of Seil, and

inside the dark heights of Kerrera, by a narrow sound to reach its port at

Oban, whose once mighty strongholds are overshadowed by such an eruption

of smart hotels and villas.

Here we come into touch with the Caledonian

Railway, which is the shortest way to this "Charing Cross of the

Highlands." Having entered the mountains beyond Stirling Castle and

Dunbiane, passing near the Trossachs and under the Braes of Balquhidder,

the line turns westward to wind through the mountains of southern

Perthshire, and reaches Argyll by some of Scotland's grandest scenes,

finding a way between the head of Loch Awe and the mighty Ben Cruachan,

after a glimpse, at Dalmally, into the strath of Glenorchy, oasis-like

after terrific Glen Ogle and dreary Glen Lochy. The railway holds on

through the stern Pass of Brander, scene of the Highland Widow, where

cairns still record the crushing of the Macdougalls of Lorne by Robert

Bruce. Then we gain Oban by Loch Etive, whose upper part runs into one of

the grandest of Highland glens, and its waters rush out with the tide in

Ossian's Falls of Lora, through the narrow throat now bridged by a branch

to Ballachulish.

On one side, this line takes in tributaries of tourist

traffic from Loch Earn and Loch Tay, and roads through the grand

Breadalbane Highlands marked by their name as heart of ancient Albin. On

the other side, by coaches and steamboats, Ben Cruachan is reached from

Inveraray or from the head of Loch Long. Campbell seems the dominant name

now in this country, but once it was the land of the Macgregors, whose

hearts still turn to fair Glenorchy, whence they were driven landless and

nameless. This ancient clan stood as model for Scott's Vich-Alpines, a

name which they in fact claim as descended from Gregor, son of King Alpin.

Not every one reads Scott nowadays; few read his introductions and

miscellaneous essays; and perhaps nobody, without special interest in the

subject, will go through Miss Murray Macgregor's elaborate history of her

name; so there will be many of my readers to whom may not come amiss a

short digression on the peculiar fortunes of a clan distinguished by

ferocity among warlike neighbours in a ruthless age. It was not the Saxon

that to them "came with iron hand," but men of their own blood and speech,

who "from our fathers rent the land" about which the moon could be

significantly known as "Macgregor's Lantern," as also indeed "Macfarlane's

Lantern," and the lamp of other Highlandmen bent on business that would

not well bear brighter light.

From very early times the Macgregors

passed for Ishmaelites, every hand against them, their fastnesses again

and again threatened by commissions of fire and sword as soon as troubled

Scottish kings could attempt to settle the quarrels of the Highland

border. Their most resounding offence was the slaughter of the Colquhouns

at Glenfruin by Loch Lomond, a little before James VI. posted off to his

softer throne in London. This was a fair fight, made flagrant in tradition

by the murder of the Dumbarton schoolboys who had come out to see the

battle, as in our day lads might go some way to a football match. It is

stated that the Macgregor chief bid these non-combatants take refuge in a

church, either to keep them out of the way of shots, or to have under his

hand a troop of hostages from among the principal families in Scotland;

and that it was his foster-brother or some of his followers who stabbed

the unfortunate youths, to the chief's indignation. Another legend tells

of a barn in which the poor boys were burned to death. One tradition

points out two murderers, who henceforth lived as outlaws from the clan.

Miss Murray Macgregor naturally defends her kinsmen from the charge of an

atrocity so heavily weighing on their own conscience that for long no

Macgregor would cross after nightfall the stream in that "Glen of Sorrow,"

believed to be haunted by the ghosts of the victims. It is in print,

though I cannot find any authority of weight, that up to the middle of the

eighteenth century the Dumbarton schoolboys annually went through a

ceremony of funeral rites on what was taken for the anniversary of the

massacre, their dux being laid on a bier and with Gaelic chants carried to

an open grave as effigy of those luckless predecessors.

The story of the

scholars may have been exaggerated. But when eleven score widows of the

slain Colquhouns, dressed in black on white palfreys, each bearing her

husband's bloody shirt on a spear, came before James demanding vengeance,

this object-lesson deeply moved the pacific king. The very name of

Macgregor was proscribed on pain of death. The clan was handed over to the

Campbells for execution; and when its chief surrendered to Argyll on

promise of escaping with exile, this condition was kept to the letter by

sending him over the English border and at once bringing him back to be

hanged at Edinburgh. Throughout the century, acts of proscription against

the Macgregors were repeatedly renewed, most of them having to disguise

themselves as Campbells, Drummonds, Murrays, or other neighbour names,

while one branch, settled in Aberdeenshire, took that of Gregory, and some

wandered north as far as Ross. The bulk of their lands passed to the

Campbells. But still a tough stock of them held fast near their old seats,

not to be rooted out by all the power of the crown or of the Campbells, as

we know from Rob Roy's exploits, who, "ower bad for blessing, and ower

good for banning," hardly played the hero in the political strife of his

day, but did a good deal of doughty fighting for his own hand.

This last

of semi-mythical heroes had come to look on Argyll as a protector, and

turned his depredations chiefly against the house of Graham; whereas in

the former century many of the clan had followed Montrose, which was worth

to them the favour of Charles abolishing the penal laws against their

name, afterwards reenacted under William. It was not till George Ill.'s

reign, when the tamed Macgregors had amply proved their loyalty in arms as

well as their ability in other walks of life, that their proscription was

finally annulled, the scattered clan free to take their own name, for

which they recognised Sir John Murray as chief, in a deed signed by over

800 Macgregors. Rob Roy had represented the junior branch of Glengyle,

claiming descent from that ruffian on whom was laid the blood of the

Dumbarton scholars. Rob appears to have died a Catholic; but a

contemporary divine of his clan tells how they were in the way of boasting

that they had a religion of their own, "neither Papist nor Protestant,

just Macgregors! " So much for a stock that seems to have been more

unlucky but not more undeserving, perhaps, than its neighbours.

In the

Macgregor country the Caledonian line crosses its rival the West Highland

Railway, that from Helensburgh turns northward up the shores of Loch Long

and Loch Lomond to mount into the wilds of Perthshire, the great

Caledonian Forest of old, still showing a wide waste, the Moor of Rannoch,

about which lay hid Charles Edward in fact, as Stevenson's David Balfour

in fiction slunk before the redcoat dragoons over that naked moorland,

crawling on all fours from patch to patch of heather among its moss bogs

and peaty pools. Above the loftiest point of the line stands a

shooting-lodge which used to boast itself the highest habitation in

Britain, but has been far overtopped by the Observatory on Ben Nevis,

round whose snow-streaked flanks the railway turns west at Fort-William

towards its terminus on the coast.

This is bound to be a somewhat flat

chapter, in which one can merely hint at the landmarks of rapid routes to

the Inner Highlands, most of them by scenery already traversed in Bonnie

Scotland. From Ben Nevis there is a straight way to Inverness by the bed

of the Caledonian Canal. To that "capital of the Highlands," the highroad

from the centre of Scotland is by the famed Highland Railway over the

wilds of Atholl and Badenoch. Other lines lead less directly from the

south to Inverness. The Caledonian through Strathmore, and the North

British over the Firths of Forth and Tay, unite to reach Aberdeen by the

rocky coast on which stands out Dunottar Castle, that old Scottish

Gibraltar, honoured with the custody of the Regalia, and accursed by the

cruel confinement of Covenanters. At Aberdeen, close to the rounded and

trimmed beauties of Deeside, avenue for Balmoral and Braemar, one has a

choice of routes to Inverness, over a fine half-Highland, half-Lowland

country, or along the rocky coast of the Moray Firth.

From Inverness a single line runs on to the far north, with a branch to

the ferries of Skye, rivalled now by the West Highland extension to

Mallaig. Half a century ago Dean Stanley declared it easier to get to

Jerusalem than to Skye. Jerusalem to-day has its railway ; while Skye is

reached by steamers from Oban, besides the easy crossings for which

cyclists wind upon good roads through the bens and glens beyond Inverness.

Oban, Fort-William, and Inverness are the chief bases of West Highland

touring. To Lorne and to Lochaber we shall return anon. Of Inverness,

properly a Highland frontier city, if capital of the Highland Railway,

enough has been said in my former volume; but here I would take the

opportunity of correcting a slight anachronism by which I there spoke of

Inverness Castle as used for a prison. I learn that within the last two or

three years it has been freed from this degradation. The Highlands have

not much need of prisons; the Fiji Islanders did not more quickly shift a

character for fierce violence. But for whisky and political or religious

agitation, there would be little need of police in this country. It is

many a year since a Highlander was "justified." During the last quarter of

a century or so, some half-dozen executions have served all Scotland; and

it is stated on good authority that not one of the criminals was of native

blood or religion indeed, sound Presbyterians have the satisfaction of

noting—but let sleeping dogs lie!

Peacefulness and honesty were not

always characteristic virtues of the Highlands; and even yet, now that we

are about to visit Donald in his native wilds, let us understand how, like

the rest of us, he has his weak points as well as his strong ones, both of

them sometimes exaggerated into a caricature as like the original as is

the rigid Highlander of a snuff shop. His critics are apt to dwell on

certain faults which may be often regarded as the seamy side of fine

qualities that also distinguish him. His groundwork of laziness will be

chequered by spells of energy and endurance. He may still put too much of

the hard drudgery on women; but he does not shrink from tasks of danger

and death. His want of smart practical turn goes with his readiness for

romantic imaginings. His hot temper is related to a pride that begets

chastity and courtesy as well as brawls. His loves as well as his hates

catch fire more briskly than in the coarser Saxon nature, whose

affections, indeed, if harder to kindle, may burn with an intenser glow

when once well alight. The Lowlander is a better man of business, but the

Highlander more of a gentleman, as the stranger will soon remark. And now

that old feuds have smouldered out, the dourest Whig will not care to

contradict a Tory poet—

Nowhere beats the heart so kindly

As beneath the tartan plaid.

All the same, Aytoun might have found

cause to choose another epithet for Highland hearts, if, in those loyal

old days of his, wearing a MacTavish plaid, let us say, he had chanced to

forgather on some lonely moor with the tartans of "ta Fairshon."