The Highland Line is an oblique one, in the main facing

south-east; and in much the same direction, between the head of deep

inlets, extends the cleft of some threescore miles that cuts the Highlands

into near and off halves, the former far the harder worked as a tourist

ground, the latter retaining more of its Celtic poverty, while not less

richly endowed by nature. From either side smaller glens and straths, each

the "country" of some clan, debouch into Glenmore, bed of a chain of lochs

and streams linked together as the Caledonian Canal, their varying levels

made navigable by the locks that come easier to a Sassenach tongue. This

canal is now nearly a century old. In the century before its trenches were

opened, King George's soldiers had islanded the farther Highlands by a

road between three fortified posts, in the centre and at either end of

this Great Glen, thus used as a base for dominating and civilising a

region over which the fiery cross ran more freely than the king's writ.

The northernmost of the three, Fort-George, above Inverness, is still a

military station, serving as depot for the Seaforth and Cameron

Highlanders.

Inverness is called the capital of the Highlands,

though it lies on an edge of Celtic Scotland, at the north end of the

Great Glen, and near the head of the Moray Firth. This is not a Gaelic

city, whose inhabitants had at one time the fame of speaking the best

English in Scotland, or, for the matter of that, in England, a merit

sometimes traced back to a colony of Cromwell's soldiers. Of late years,

to tell the truth, the speech of Inverness has hardened and vulgarised

somewhat in the mouths of a very mixed population; yet still in some of

the secluded glens of the county may be heard a tongue not their own used

with a melodious refinement unknown within the sound of Bow Bells.

Smart, cheerful, and regularly built, Inverness has the

air of a lowland town, spread out on a river plain, across which fragments

of the Highlands have drifted from the grand mountains in view, as the

Alps from Berne. The Ness has the distinction of being the shortest river

in Britain, shorter even than London's New River ; but its course of only

a few miles, from Loch Ness to the Moray Firth's inner recess, is enough

to make it a resort for big salmon and small shipping. Hector Boece

records a former great "plenty and take of herring," which vanished "for

offence made against some Saint." Sheltered from the winds of the east and

the "weather" of the west, the district has a genial climate where,

indeed, the air often "nimbly and sweetly recommends itself unto our

gentle senses." Shakespeare, not having the advantage of Black's Guide,

says little about the scenery around, which has been much described in

Wild Eelin, William Black's last and not his worst novel, though it

has the deplorable fault of

Inverness from near the Islands

bringing in real personages not less thinly disguised

than Inverness is as Invernish.

The famous Castle still stands by the river-side, in

its modern form serving as a court-house and prison for ungracious Duncans

made both drunk and bold; while the grounds of its "pleasant seat" are a

lounge for honest inhabitants, kept in memory, by a statue of Flora

Macdonald, how Prince Charles Edward's men blew up the old blood-stained

walls. Opposite, across the river, is the modern Cathedral of the

Episcopal Church, here a considerable body which once had a soul of

Jacobite sentiment. Inverness shows several fragments of antiquity, most

revered of them that palladium Clach-na-Cudain— "stone of the tubs," now

built into the base of the restored Town Cross. A little way up the river

its "Islands" have been adapted as a unique "combination of public park

and natural wilderness, of clear brown swirls and eddies under the

overhanging hazels and alders, and open and foaming white cataracts where

artificial barriers divert the broad rush of the river." This beauty-spot

of wood and water no stranger should fail to seek out; then not far beyond

he may gain Tom-na-hurich, "hill of the fairies," which makes a

picturesque cemetery, commanding what a pre-Wordsworthian writer describes

as "a boundless view of gentlemen's seats, seated generally under the

shelter of eminences, and surrounded by wooded plantations." Another fine

prospect can be had a mile or so behind the station from the heights

called "Hut of Health," on which have been built extensive barracks.

The hotels of Inverness are not too many to accommodate

the crowds that flit through it in the tourist and shooting season. It has

two annual galas, when accommodation may be hardest to find for love or

money. The first is the "Character Fair" in July, so called because then

some half a million changes hands over dealings in wool on the security of

the dealer's character, not a fleece being brought to market, nor even a

sample, unless of human brawn and beards well displayed in the brightest

of tartan and the roughest of homespun. The second is the Northern Meeting

in September, gayest and smartest of those gatherings by which the old

Highland games, dress, and music are kept up. But ah ! this touch of local

colour is too like the artificial bloom on a faded cheek. The glow of

tartans here revived by what a German might call "Sunday Highlanders," is

but a Vanity Fair. The stalwart athletes, some of them "professionals,"

who exert themselves to make a London holiday, have little more of

Arcadian simplicity than the fine folk who look on. The clansmen forget

old feuds; the chiefs no longer command the old loyalty; the greyness and

greed of our practical world are settling down over the Highlands,

conquered by gold, as hardly by southron steel.

If the

pensive tourist seek a purer vision of the past, let him go out to the

lonely station of Culloden Moor, some half a dozen miles from Inverness.

From the great viaduct that here typifies modern enterprise, he may hold

up the Nairn to the roughly overgrown field on which are half buried those

pre-historic stones of Clava, monuments of a past beyond Scott's ken.

Then, crossing the river and mounting the heights, he comes on the

commonplace road that will lead him over Drumossie, where the romantic

cause fell hopelessly when Cumberland's red-coats mowed down and bayoneted

its jealous, sullen, and weary champions, more than a tenth of them dying

here for the Prince who, according to one story, fled basely, but others

report him as forced from the field. Fir plantations and fields have now

clad the wild nakedness of this tableland ; but by the roadside are seen

the mounds beneath which lie each clan together, still shoulder to

shoulder, and the monumental cairn that is yearly hung with votive wreaths

by a certain perfervid Jacobite. If these men gave way before disciplined

valour and artillery, if their own martial spirit was marred by

quarrelsome ill-temper, let us remember how many of them joined or

rejoined the cause when it was as good as lost, after the Jacobite squires

of the south had held back from its first flush of success. The next time

the Cockney be moved to his sneer about bawbees, let him consider how

neither bribes, nor threats, nor torture could tempt these poor

Highlanders to betray their prince in his desperate wanderings with a

price set on his head. And let us all forget, if we can, the cruelty with

which the victors followed up that last rout of sentimental devotion. One

poor fellow took hundreds of lashes on an English ship of war, without

opening his mouth to confess how he had ferried the fugitive to a safer

isle. Such stories of humble fidelity are too much forgotten by historians

who bear in mind how the heads of certain houses — father and son — ranked

themselves on opposite sides with a politic eye to escape forfeiture,

whether James or George were king. The most romantic case, if true, is

that of the Macintosh in the royal ranks, said to have yielded himself

prisoner to his own wife, who had taken his place at the head of the

rebellious clansmen. Another family manoeuvre turned out luckily for a

Lowland peer who, as preparation for taking the field with the Pretender,

treated himself to a foot-bath which his prudent wife made so hot that her

valorous spouse could not boot nor spur for many a day, and thus was kept

out of political hot water. The same story, indeed, is told of another

couple, whose sympathies were divided the opposite way on.

Where are the sons of the scattered clans? Many of them

peacefully settled among law-abiding Lowlanders, many of them gone to

America, where among other mountains, on fruitfuller straths and by

mightier streams, they often cherish their Gaelic and their kilts,

sometimes against sore pricks of climate and mosquitoes, sharper than the

ancestral itch of dirt and poverty. In one district of Nova Scotia alone,

there are said to thrive three thousand of those Macdonalds whose offended

pride hung back from the clash of Culloden. Before the '45, emigration to

America had already begun with the colony settled in Georgia by General

Oglethorpe; even earlier indeed hardy Highlanders and Orkneymen were in

demand for service in the wilds of Hudson's Bay; but after Culloden the

exodus became considerable, increasing as the chieftains, turned into

lairds, found idle and prejudiced dependants only in the way of improving

their estates; and "another for Hector!" came to mean a fresh clansman

shipped across the Atlantic to see Lochaber no more. Harsh as it was, the

wrench proved often a blessing in disguise, when the last look at those

misty Hebrides had softened into a tender memory with the farmers of New

Glengarry or ice-bound Antigonish. Our day saw two Prime Ministers of

Canada who, if kept at home, might have

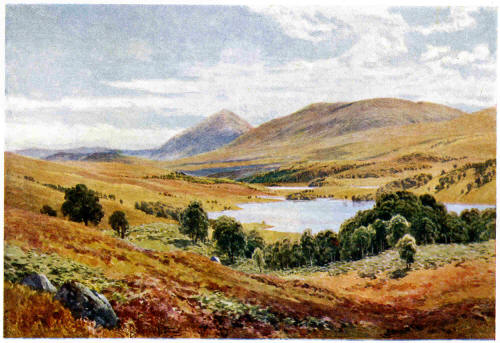

Tomdoun, Glen Garry, Inverness-shire

been carrying the southron's game-bag, as one of them

perhaps did in his bare-legged youth.

Perhaps the most remarkable Highland-American has never

been duly brought into the light of history, as neither has that

mysterious soldier of fortune Gregor MacGregor, "Cacique of Poyais," who

made such a stir in two worlds, but is now hardly remembered unless by the

mention of him in the Ingoldsby Legends, and the banknotes of his

bankrupt kingdom, treasured by collectors of curiosities. Did the general

reader ever hear of Alexander MacGillivray, who was born at once a

Highland gentleman and a Red Indian chief? His career, which I hope to

write some day, if once able to bridge over certain gaps in my

information, makes an extraordinary mixture of romance with very opposite

features, better fitting the vulgar idea of a Scot.

Some time during the Jacobite disturbances, one Lachlan

MacGillivray emigrated from Inverness to the Southern States, where he

became a prosperous Indian trader, and, perhaps in the way of business,

married a "princess" of the great Creek Confederacy. Alexander, the son of

this mesalliance, was well educated and brought up to trade, but early in

life betook himself to his mother's people, among whom his attainments as

well as his birth gave him influence. Rank, by Indian law, as by "Lycian

custom," being inherited on the spindle side, before he was thirty he had

been recognised as chief of the Creeks, and for many years played a

leading part in their fitful politics. Little is known of his rule beyond

the main facts, our clearest accounts of him being derived from a rare

book written by another young adventurer, the Frenchman Leclerc Milfort,

whose story, in plain English, seems not to be always trusted.

According to himself, Milfort, having also wandered

among the Creeks, was chosen by them as their war chief, an office

separate from the civil headship of an Indian tribe. Then the Scotsman and

the Frenchman appear to have governed the Creeks for years, making a

congenial disposition of power, the one the head, the other the hand, of a

powerful though somewhat unstable body politic. MacGillivray had no

stomach for fighting, was even a coward, if Milfort is to be believed; but

he was crafty, resourceful, and of a clear Caledonian eye to the main

chance. Milfort found him living in a good house, with herds of cattle and

dozens of negro slaves. Another source of profit he had in a secret

partnership with a firm of brother Scots at Pensacola, to which he

directed the trade of the Creek nation, jealously intrigued for by their

British and Spanish neighbours. The Revolutionary War had nearly caused a

rupture between these Creek consuls. MacGillivray's sympathies were with

the British; Milfort had no scruple in fighting against the Americans, but

when French troops came to take part in the struggle, he was disposed to

side with his compatriots. His colleague, however, persuaded him to remain

neutral; and by this Scotsman's influence, the Creeks seem to have been

kept from throwing into the scale the weight of their war parties. The

canny chief entered into a maze of tricky negotiations with the various

bordering Powers, pretending to each to be in its special interest,

receiving bribes from all, throughout, as far as his dealings can be

traced, "true to one party, and that is himself."

The States having secured their independence, the

eagerness of American settlers to press over the Creek bounds had almost

brought about an Indian war with the great republic. Scenes of bloodshed

took place on the frontier; and if MacGillivray was cunning and not

warlike, he showed the civilised virtue of humanity in sparing and

rescuing captives. Peace was negotiated by an Indian deputation which he

led to New York. A secret article provided for his being appointed a

general in the U.S. service, with a pension of $1200. At the same time, or

soon afterwards, the wily chief accepted similar distinctions and payments

from the British and the Spanish Governments, and between them he must

have enjoyed a considerable income for steadily promoting his own

interests, while impartially betraying all his rival employers in turn.

But the arrangement which he brought about with young

Uncle Sam roused the Indians against him. A rebel leader appeared in one

"General" Bowles, who, originally a private soldier, in the course of many

dubious adventures more than once played the pretender among the Creeks. A

civil war raged in the Confederacy; MacGillivray at one time was driven to

flight; but, still backed up by Milfort, he succeeded in partly restoring

his power, though not with the same firmness. In the middle of his

tortuous policies, he died at the age of fifty, leaving a son, who was

sent home to Scotland, where old Lachlan is said to have been still alive

in Inverness-shire. It was his half-breed nephew, William Weatherford,

who, later on, led the last struggle of the Creeks against American

encroachment.

As for Leclerc Milfort, he was left for a time

struggling against Bowles and other rivals for authority. According to his

own story, the French Revolution brought him back to France, where he

laboured to persuade Buonaparte how easily an empire might be won in

America. It is said that the First Consul was taken by the idea, and that

in 1801 a small French expedition had even been prepared to conquer the

Creek country under Milfort's guidance. But vaster plans interfered with

any such scheme, and in 1803, Louisiana and the great South-West were sold

by France to the United States. The ex-chief had a chance to gratify his

taste for fighting at home, when France was invaded in 1814; but he did

not return to resume the authority of which he boasts in his book, so rare

that I have never seen a copy except my own. If one only had all the truth

about these two white adventurers, what a strange romance it would make!

The Highlands may be all the more prosperous for the

new husbandry that drove so many of their sons to seek fortune in distant

lands, often to find fame. It might be well for the people to have such

enterprise roughly forced on a conservative spirit which scowled at the

introduction of potatoes, turnips, and other improvements to their

backward culture. What their good old days were in truth may be guessed in

the smoky huts where they still love to pig together, stubbornly refusing

to adapt themselves to an order in which sheep are found more profitable

than men, and deer than sheep. The big sheep-farmer from the south makes

more of the land than the easy-going crofter; yet the smallest drop of

Celtic blood cannot but stir to see a clansman touching his hat for tips

from

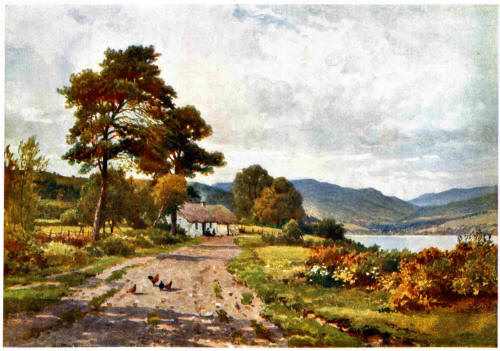

A Shepherd's Cot in Glen Nevis, Inverness-shire

southron stockbrokers, and serving as obsequious

attendant to the American millionaires who enclose his native heath.

Naturally the Highlander is a gentleman, for all his faults, with

instinctive courtesy to soften his somewhat sullen pride. More than once I

have had a tip refused by a Highland servant, as nowhere else in the world

unless in the United States before their social independence, too, began

to be demoralised by the largesses of successful speculators, who, after

piling up dollars by "rings" and "corners," find they can buy less

observance for their money at home than by corrupting a race declared by

Mrs. Grant of Laggan, herself reared in America, "to resemble the French

in being poor with a better grace than other people."

The Highlander was a born sportsman as well as a

gentleman, who by his paternal chiefs would not be called closely to

account for every deer and salmon that went to eke out his frugal fare.

Now he can shoot or fish only in the way of business, the very laird

making two ends meet by letting out his moors and streams to a stranger,

in whose service the sons of warriors play the gamekeeper and gillie, with

more or less good will, loading the gun and carrying the well-stocked

luncheon basket, perhaps not always very hearty in hunting down those

Ishmaelite brethren who do a little grouse-netting on their own account

for the supply of London tables by the 12th of August. Sometimes the Gael

takes revenge by being able to hint his scorn for the sportsmanship of

these new masters; but as often, to do them justice, they will not give

him this poor satisfaction. A well-known southron humorist tells a story

which needs his voice to bring out the point, how he missed a deer, to the

disgust of the keeper, and how, trying to conciliate this worthy by

admiration of a fine head, he got the dry answer—"It's no near so fine as

the one ye shot this morning—a-a-at!"

Deer-stalking is a sport that still demands manly skill

and hardihood, however many menials can be hired to mark down and

circumvent the great game. So much cannot always be said of other

shooting, when the noble sportsman entrenches himself behind

fortifications to which the fierce wild fowl are driven to be shot down by

gun after gun placed in his hands. Sport, that was once a bond between

classes, becomes more and more a monopoly of the rich. The very meaning of

the word suffers a change in our day from the doing of something oneself

to a performance where most of the activity is by paid assistants or

"professionals." One good feature of Highland sport is in not lending

itself to the collection of gate-money from a mob of lookers-on ; but the

dollar-hunting and coup-landing chieftain need not expect to be

loved by those whom he would fain bar out of his solitary playground.

I, too, have lived in Arcadia, and was duly entered at

this craft, not that I ever took very heartily to it, or that a big

capercailzie, then a rara avis in Highland woods, ran much more

risk from me than from Mr. Winkle. But I know the free joy of tramping

over wet moors behind dogs, shooting for sport and not for slaughter,

lunching off bread and cheese, or a cold grouse, with fingers for forks,

and coming home to a dinner won by one's own hands. That old-fashioned

muzzle-loading work is scorned by the present generation who, indeed, pay

such rents for moors and coverts that they have some reason to be keen

after a big bag. Well I remember a true Nimrod's scorn for the first great

noble in our part of the world who sold his game! We children in

the nursery would be fed on grouse and salmon to use up what could not be

sent away as presents; and, for my part, I have never quite got over a

stickjaw conception of these expensive dainties.

There was a Highland shooting which in those days

seemed a paradise of schoolboy holiday. It belonged to a well-known

Scottish peeress married to a French nobleman, on whom it was thrown away,

though their son grew to be of a different mind. Thus it came on a long

lease into the occupation of keen sportsmen of my family, who naturally

did not care to build for their inevitable successors. The "lodge" was a

short row of white cottages, the centre one turned into a parlour, the

others into bedrooms; and as youngsters grew up, extra accommodations were

provided in the shape of a tent and iron shanties, the whole group backed

by a thin clump of wind-blown firs visible some dozen miles away on the

bare mountain side. All through the summer months it made an encampment

for a band of kilted youngsters, "hardy, bold, and wild," taking in the

Highland air at every pore, with miles of moor and burn for their

playground, which they knew not to be haunted by the victims of Druid

rites. Not that more sophisticated guests were unknown at this eyry of

eyases. The great little Earl Russell, at that time, if I am not mistaken,

Prime Minister, was tenant of a neighbouring moor. One day he had come

over for a sociable beat, broken in on by a messenger, hot foot across the

heather, bearing a huge official envelope superscribed with the name of a

ducal colleague. The statesman requested a private apartment in which to

examine this communication, but the only-closet available was a bedroom,

where he opened the cover to find—a caricature of himself from Punch

!

I have been led away by a grumble at the self-indulgent

and well-appointed sportsmen who in this generation invade my native

heath. But, however much they make themselves at home here, we chuckle to

think that they at least cannot tune their ears to the native music. For

what says the poet—

A Sassenach chief may be bonnily built,

He may purchase a sporran, a bonnet, and kilt;

Stick a skean in his hose—wear an acre of stripes—

But he cannot assume an affection for pipes.

Another comfort taken by the dispossessed son of the

mist is in hearing the weather abused by strangers, who may as well stay

at home under shelter of their Twopenny Tubes and Burlington Arcades if

they are afraid of rain. Dr. Johnson was not, and a gentler critic of his

time observed that the Highlanders minded snow "no more than hair powder."

In the warm south of England, I once caught a cold which stuck to me all

summer and seemed like to settle on my lungs. Late in autumn, in a kill or

cure mood, I went down to the dampest side of the Highlands, got wet from

morning to night, and in a week my cough had gone like dew from the

heather. But nature's hydropathy does not always work so well, even on

seasoned constitutions. The severest loss of our Volunteer force, as yet,

on British soil, has been from that soaking royal review at Edinburgh,

when Highlanders were killed and crippled by a long railway journey in

drenched clothes, even though at the way-stations matron

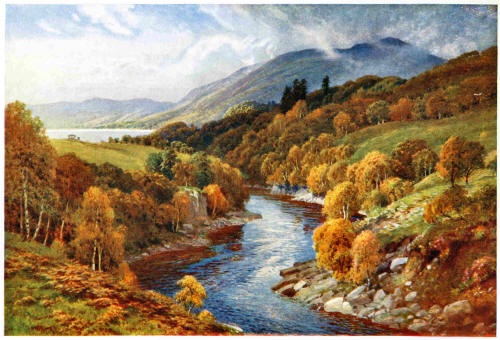

River Awe flowing to Loch Etive, Argyllshire

and maid brought them patriotic offerings of dry hose,

with which at least to " change their feet."

Now let us turn to the tourist, who has neither lust

nor license to ruffle the least feather of grouse or gull, but calls forth

angry passions when his red guide-book or her sunshade come scaring the

prey stalked by lords of Cockaigne and Porkopolis. He and she, by coveys,

swarm in various directions from Inverness, but chiefly by the Caledonian

Canal, that highroad of pleasure, as once of business, between the North

and the South Highlands. Had we seen this road "before it was made," we

should find little difference to-day, unless for a few more modern

mansions that have swallowed up many a lowly home, still, perhaps, marked

by patches of green about the ruined mountain shielings where, as on

Alpine pastures, Highland Sennerin made butter and cheese through

the long summer days. A steamboat carries one right through the Great

Glen, beneath mountain giants, clad in nature's own tartan of green and

purple chequered by brown and grey, with bare knees of crag, and streaming

sporrans of cascade, and feathers of fir-wood, too often wrapped in a

plaid of mist, or hidden by a mackintosh of drenching rain. Else, against

the clear sky-line, one may catch sight of a noble stag on the hill head,

displayed like its crest, sniffing motionless at the steamer far below,

unconscious of an unseen enemy stealing up the rearward corrie with heart

athrob for his blood, which, at the pull of a trigger, may or may not

stain the heath.

From its port below Craig Phadric, believed to have

been the stronghold of a king older than Duncan, then past the hill

bearing his name, the Canal soon takes us through the

fertile strath into the wilder Highlands. The first stage of that grand

panorama is through deep Loch Ness, where on one side Mealfourvonie towers

like a hayrick, round which goes the way to those remote Falls of Glomach,

called the noblest in Britain, and on the other are more easily reached

the Falls of Foyers, chained and set to work by an Aluminium Company that

did not tremble at the rhapsody of Christopher North:—

"Here is solitude with a vengeance—stern, grim, dungeon

solitude ! How ghostlike those white, skeleton pines, stripped of their

rind by tempest and lightning, and dead to the din of the raging cauldron!

That cataract, if descending on a cathedral, would shatter down the pile

into a million of fragments. But it meets the black foundations of the

cliff, and flies up to the starless heaven in a storm of spray. We are

drenched, as if leaning in a hurricane over the gunwale of a ship, rolling

under bare poles through a heavy sea. The very solid globe of earth quakes

through her entrails. The eye, reconciled to the darkness, now sees a

glimmering and gloomy light—and lo, a bridge of a single arch hung across

the chasm, just high enough to let through the triumphant torrent. Has

some hill-loch burst its barriers? For what a world of waters come now

tumbling into the abyss! Niagara! hast thou a fiercer roar? Listen—and you

think there are momentary pauses of the thunder, filled up with goblin

groans! All the military music-bands of the army of Britain would here be

dumb as mutes—Trumpet, Cymbal, and the Great Drum! There is a desperate

temptation in the hubbub to leap into destruction. Water-horses and

kelpies, keep stabled in your rock-stalls—for if you issue forth the river

will sweep you down, before you have finished one neigh, to Castle

Urquhart, and dash you, in a sheet of foam, to the top of her rocking

battlements. . . . We emerge, like a gay creature of the element, from the

chasm, and wing our way up the glen towards the source of the cataract. In

a few miles all is silent. A more peaceful place is not among all

the mountains. The water-spout that had fallen during night has found its

way into Loch Ness, and the torrent has subsided into a burn. What the

trouts did with themselves in the 'red jawing speat' we are not naturalist

enough to affirm, but we must suppose they have galleries running far into

the banks, and corridors cut in the rocks, where they swim about in water

without a gurgle, safe as golden and silver fishes in a glass-globe, on

the table of my lady's boudoir. Not a fin on their backs has been

injured—not a scale struck from their starry sides. There they leap in the

sunshine among the burnished clouds of insects, that come floating along

on the morning air from bush and bracken, the licheny cliff-stones, and

the hollow-rinded woods."

At the head of Loch Ness our boat takes to locks again

at Fort-Augustus, now turned into a Catholic monastery, arms yielding to

the gown. Hence, if the rain persistently blot out all prospect, we might

hasten on by branch railway to the West Highland Line, passing near those

geological lions called the "parallel roads" of Glenroy. Else we thread

the water between the heights of Keppoch and Glengarry, marked by the

cairns of many a forgotten feud, and through Loch Oich and Loch Lochy come

to cross the West Highland Railway at Banavie, where the Canal descends to

sea level by a staircase of locks like that at Trollhatta on the not less

famous waterway from Gothenburg to Stockholm.

Loch Oich, the smallest of the chain into which the

Garry comes down from its basin, has an authentic legend as retreat of

Ewen Macphee, perhaps the last British outlaw above the rank of a lurking

poacher or illicit distiller. Early in the nineteenth century he enlisted

in a Highland regiment, from which he deserted, and though captured and

handcuffed, made a romantic escape to his native wilds of Glengarry. After

camping in the woods till the hue and cry after him had died out, he

settled on an islet of Loch Oich, where he took to himself a wife and

reared a sturdy brood. For long he played Rob Roy on a small scale,

"lifting" sheep and helping himself to game, while he enjoyed the sanctity

of a seer's reputation. When a southern landlord bought the property, he

established a not unfriendly modus vivendi with this tackless

tenant, who introduced himself to the new owner by sticking his dirk into

the table as title-deed to his island—"By this right I hold it!" But by

and by the minions of the law pressed upon his retreat; and in spite of a

resolute defence, in which his wife handled a gun like a modern Helen Mac-gregor,

he was arrested for sheep stealing, and taken to prison, where he pined

away after a long life of lawless freedom. Bales of sheep skins and

tallow, found hidden about his fastness, were evidence of how he had lived

at the expense of his neighbours, a feature too much left out of sight in

modern regret for the picturesque old times.

Banavie—that seems to be a kilted cousin of Banff, and

forebear of the Rocky Mountain paradise an American geographer presumes to

spell Bamf—is close to Fort-William, the southernmost of the three

military posts that bridled the Great Glen. In Stuart days this was

Inverlochy, scene of that battle between Montrose and Argyle. It is now a

town of snug hotels, over which rises the proclaimed monarch of British

mountains, his gloomy brow often crowned with mist and his precipitous

shoulders ermined with snow at any season. But if the weather favour, from

the Observatory Tower at the top,

A Croft near Taynuilt, Loch Etive, Argyllshire

wild magnificence. Now the West Highland Railway takes

one on through Glenfinnan and the Lochiel country, where Charles Edward

raised that last standard of rebellion, against the prudent judgment of

the Cameron chief whose loyal pride yet followed it to Culloden, and where

a tall column records how a later Cameron fell as gallantly in the service

of the established dynasty. Thus we come to Arisaig on the west coast, and

to Mallaig opposite Skye, in which a book that draws to its end must not

venture to enter upon the most gloomily grand aspects of Highland scenery.

All this, like the country above the Moray Firth, comes under the head of

"counsels of perfection"; but every conscientious Highland tour takes in

Inverness, on the round made by the Highland Railway and the Caledonian

Canal, the most perfunctory minimum being the Trossachs trip, which might

be extended to pass by Oban and the Clyde.