Unless for that modern knight-errant, the cyclist,

speeding to achieve the quest of John o' Groat's House, the far northern

Highlands seem as unduly neglected by tourists as the southern mountains

of Wales. Yet across the Moray Firth, that half insulates the north end of

Britain, lie charms and grandeurs none the less admirable for being

somewhat out of the scope of tourist tickets. The best face of this region

it turns to adventurers who brave the Hebridean seas; but also it has

winning smiles and impressive frowns for those who on the east side follow

the Highland line to its Pillars of Hercules.

The railway to the far north begins by running westward

from Inverness to round the inner basin of the Moray Firth at Beauly,

indeed a Beau lieu. Here, beside the ruins of a priory, is a seat

of Lord Lovat, whose shifty ancestor, after Culloden, lurked for six weeks

in a secret chamber of Cawdor Castle, but was finally run down in a hollow

tree after adventures trying for the age of fourscore and four. The falls

of Kilmorack make perhaps the finest point in a district full of

attraction. Gilliechrist is noted for a grim story that does not go

without question: in the church here a congregation of Mackenzies is said

to have been burned alive, to the sound of the bagpipes, by their

Christian enemies of Glengarry, a memory of ancient manners which

Wordsworth laments as "withering to the root." One of Lord Lovat's

hiding-places was an island in the river, that afterwards became a summer

retreat of Sir Robert Peel ; and its romantic cottage was for a time the

home of the two Sobieski or Allan brothers who made a mysterious claim to

represent the Stuarts, and were treated with royal honours by some

Scottish families. They were a stately pair, after a somewhat theatrical

style, taking the part of silent Pretenders in the Highland dress, on

which they published a sumptuous volume. In later years, when both were

well-known figures in the Reading-room of the British Museum, they, or at

least one of them, came down to lodgings in Pimlico, where I have heard

pseudo-majesty calling for his boots from the upper floor like a dignified

Fred Bayham.

All this part of the railway is set among varied

beauty, as it bends away from the western mountains and curves about the

heads of the deep eastern firths. Beyond Beauly, it crosses the neck of

the peninsula called the Black Isle, on which stand the ex-cathedral city

of Fortrose, and Cromarty on the deep inlet guarded by its cave-worn

Sutors, where one can ferry over the mouth of this Cromarty Firth to the

farther promontory, ended by one of Scotland's several "Tarbets," name

denoting an isthmus or portage. Cromarty no longer exists as a separate

and much-separated county, of which Macbeth seems to have been Maormor or

satrap. Before the boundary

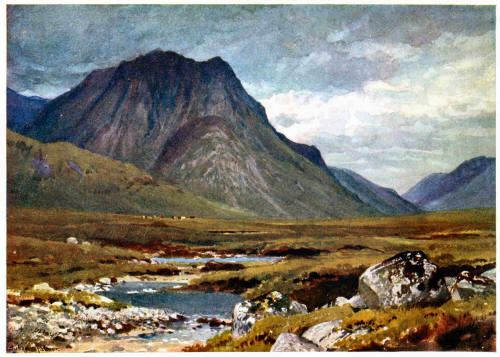

The River Glass near Beauly, Inverness-shire

adjustment in our generation, several Scottish shires

had outlying fragments islanded within their neighbours' bounds, an

arrangement probably due to the intrigues of interested nobles ; but this

one was all disjecta membra, the largest lying away up in the

north-west corner of Ross, with which environing county Cromarty is now

incorporated. The county town, at the point of the Black Isle, still

flourishes in a modest way, after shifting its site so that the Cross had

to be bodily removed. It has reared at least two notable sons, one that

literary Cavalier Sir Thomas Urquhart, who so well translated Rabelais

while a prisoner in the Tower, whence he published other ingenious works

that but feebly represent his industry, for some hundreds of his

manuscripts, lost at the battle of Worcester, went to such base uses as

lighting the pipes of Roundhead troopers. The other was Hugh Miller, the

stone-mason's apprentice, who rose to be an esteemed author, a geologist

of note, and editor of the Witness, that full-toned organ that

lifted with no uncertain sound the testimony of the Free Church.

This end of Scotland, like the south-west, has been

strongly Whig in its sympathies. Even its Highland clans were often led by

their chiefs to support the Protestant succession. It was a Mackay who

commanded for King William against Claverhouse; the Munroes did service to

King George against the Pretender; and President Forbes of Culloden kept

the Mackenzies, or many of them, from joining the prince, who at his

mansion spent a last quiet night on Scottish soil. Hugh Miller tells us

how the Cromarty folk watched the smoke of Culloden across the Firth, of

their rejoicing for Cumberland's victory, and of their savage exultation

over Lovat's head. Religious enthusiasm here was kin to that of the

Covenanters. To the south, as we have seen, lies a belt of Catholicism;

and some glens of the Highlands shelter knots of Episcopacy; but when the

Gael does take to Presbyterianism, he likes it hot and strong. This was

the diocese of the "Men," those inquisitorial elders who played such a

severe part in church life of older days. The Free Church movement found

great acceptation in the Highlands, so much so that in many parishes the

Old Kirk has been almost deserted. And the Free Church in the far north is

still largely officered by a school of ministers, who, fervidly rejecting

the conclusions of criticism and latitudinarian liberality, are known as

the "Highland host," by humorous inversion of a phrase that once applied

to an instrument of the prelatical party. The recent broadening of this

body's base has here been fiercely resisted, some congregations even

coming to blows over Disruption principles. There was a time when the

Sabbath could be said not to come above the Pass of Killiecrankie; but now

the northern Highlands are the fastness of a Sabbatarianism that dies hard

all over rural Scotland. In Ross, the late Queen Victoria had the unwonted

experience of being refused horses for a Sunday journey by a

postmaster incarnating the spirit of John Knox; then it is understood that

Her Majesty gave directions he should in no way suffer for conscience'

sake. There were "godly" lords in these parts, to whose influence Hugh

Miller attributes this temper of faith; and here was the diocese of that

"Black John," the "Apostle of the North," whose field-preachings stirred

the bones of martyrs to old prelatic tyranny.

It is no wonder that Hugh Miller became a champion

of the Free Church in its pristine glow. Alas ! his promising career

was cut short by his own hand. It is believed that the trial of

reconciling the Mosaic geology with advancing science proved too much for

his brain. Had his lot been cast in our generation, divines of his own

beloved communion would have taught him more accommodating

interpretations, that might have helped to a longer lease of usefulness

one of Scotland's many self-taught sons, whose Schools and

Schoolmasters remains the best book on this countryside.

At Dingwall, the little county town of Ross, which,

like the Devonshire Torrington, has been fondly thought to resemble

Jerusalem in site, a short branch line turns westward to Strathpeffer, the

Scottish Harrogate, thriving apace since it got a railway. Till then its

clients were chiefly local, many of them seeking an antidote to more

potent waters distilled hereabouts ; but now in the later part of the

season it is crowded with visitors from both sides of the Border.

Strathpeffer has varied advantages to bring patients all the way from

London. It boasts the strongest sulphur water in the kingdom, also such an

effervescing chalybeate spring as is rarer in Britain than in Germany; it

has adopted peat baths, douches, and other balneological devices from the

Continent; while a remarkably good climate helps it to distinction among

northern spas. It is sheltered by mountains from the wet and windy west;

then its show of flourishing crofts, originally granted to a disbanded

Highland regiment, attests a genial summer; and beside the Pump-room

Highland Eves tempt the drinkers with tantalising piles of strawberries,

forbidden by the faculty as plum-pudding at Kissingen; but it is to be

feared that British invalids are less docile to Kurgemass rules.

The village lies in a valley begirt by charming scenery of "dwarf

Highlands" about the course of the Conon and other streams. Hugh Miller

worked here as a mason lad, and his "recollections of this rich tract of

country, with its woods and towers and noble river, seem as if bathed in

the rich light of gorgeous sunsets." The long summer evenings light up

patches of heather over which is the way to such beauty spots as Loch

Achilty, the Falls of Conon, and the Falls of Rogie, that have been

compared to Tivoli. Close at hand is Castle Leod, famed for enormous

Spanish chestnuts that give the lie to Dr. Johnson; and farther off are

other ancient mansions, Brahan Castle, whose gardens were laid out by

Paxton; Coul with its fine grounds, and the spectral ruin of Fairburn

Tower. Above the village the wooded ridge of the Cat's Back leads to a

noble view from green Knockfarril, where is perhaps the best of the

"vitrified forts" so common in the far north. Rheumatic patients would

once celebrate their cure by dancing a Highland fling before the

Pump-room, a saltatory exercise said to have originated in the experience

of a kilt among midges. To prove themselves sound in wind and limb,

Sassenach visitors might ascend Ben Wyvis, the "Mount of Storms," a

ten-miles tramp or pony ride. There is no difficulty on the way unless a

bog at the bottom, that must be skirted in wet weather ; and the prospect

from the top is rarely extensive in proportion to the trouble of reaching

it: on a fine day may be seen the mountains of Argyll, of Braemar, of

Sutherland, and of Skye, perhaps grandly half revealed through distant

haze or thunderstorm.

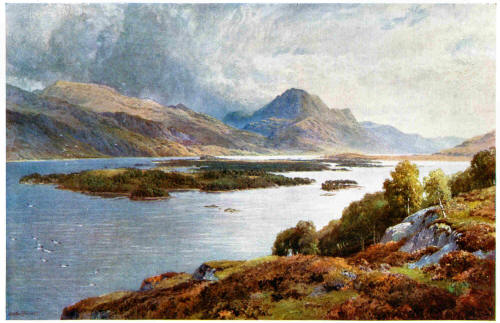

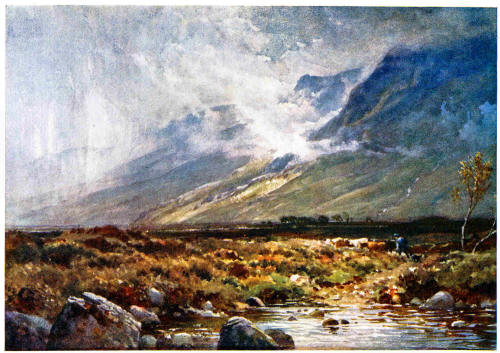

Moor of Rannoch, Perthshire and Argyllshire

At Dingwall diverges also the branch line to Lochalsh,

the ferry for Skye. This takes one through a real Highland country, where

at Auchnasheen goes off the coach route to Loch Maree, which some judge

the finest scene in Scotland. Less smiling than Loch Lomond, it lies more

wildly among naked pyramids of quartz, Ben Slioch the most conspicuous

point of them, but this lake has the same beauty of wooded islets at the

lower end, where a group of half-drowned hillocks "form a miniature

archipelago, grey with lichened stone, and bosky with birch and hazel." On

one of these are the ruins of a chapel of the Virgin Mary, who was perhaps

godmother to Loch Maree. Beyond it open the sea-inlets Torridon, Gairloch,

and Loch Ewe; and the coast northwards by Ullapool and Loch Inver is

pierced by deep fiords and overlooked by grand summits, worn down from

Himalayan masses of old. On the road from Garve to Ullapool, beside the

strath looking down to Loch Broom, an oasis of greenery enshrines the

Measach Falls of Corriehalloch, a stream tumbling through a deep-bitten

chasm, which some have pronounced the grandest Highland scene in the

genre of that Black Rock ravine mentioned below. If we are ever to

reach John o' Groat's House let us turn away from the transparent waters

of this coast and from the gloomy glories of Skye. The sportsmen to whom

these northern wilds are best known would not thank any guide of idle

tourists, and such a guide must be pitied in his task of repeating

epithets.

From Dingwall the railway holds up the side of the

Cromarty Firth by a country of Munroes and Mackenzies, who have taken all

the world for their province. A notable natural feature

here is the chasm of the Black Rock, through which a stream from Loch

Glass leaps in a series of cascades gouging out an open tunnel that

sometimes is only a few yards wide at the top, whence one looks down upon

waters foaming into gloomy linns, an American canon in miniature, its

edges bristling like the Trossachs, its mouth thus described by Hugh

Miller:—

"The river—after wailing for miles in a pent-up

channel, narrow as one of the lanes of old Edinburgh, and hemmed in by

walls quite as perpendicular, and nearly twice as lofty—suddenly expands,

first into a deep, brown pool, and then into a broad, tumbling stream,

that, as if permanently affected in temper by the strict severity of the

discipline to which its early life had been subjected, frets and chafes in

all its after course, till it loses itself in the sea. The banks, ere we

reach the opening of the chasm, have become steep and wild and densely

wooded, and there stand out on either hand giant crags, that plant their

iron feet in the stream; here girdled with belts of rank, succulent

herbs, that love the damp shade and the frequent drizzle of the spray; and

there, hollow and bare, with their round pebbles sticking out from the

partially decomposed surface, like the piled-up skulls in the great

underground cemetery of the Parisians. . . . And over the sullen pool in

front we may see the stern pillars of the portal rising from eighty to a

hundred feet in height, and scarce twelve feet apart, like the massive

obelisks of some Egyptian temple; while in gloomy vista within, projection

starts out beyond projection, like column beyond column in some narrow

avenue of approach to Luxor or Carnac. The precipices are green, with some

moss or byssus, that, like the miner, chooses a subterranean habitat—for

here the rays of the sun never fall; the dead mossy water beneath, from

which the cliffs rise so abruptly, bears the hue of molten pitch; the

trees, fast anchored in the rock, shoot out their branches across the

opening, to form a thick tangled roof, at the height of a hundred and

fifty feet overhead; while from the recesses within, where the eye fails

to penetrate, there issues a combination of the strangest and wildest

sounds ever yet produced by water: there is the deafening rush of the

torrent, blent as if with the clang of hammers, the roar of vast bellows,

and the confused gabble of a thousand voices."

Turning away from the sea, the line soon strikes it

again at the ancient borough of Tain, on the Dornoch Firth. Near the head

of the inlet we cross into Sutherland, and soon by the gorge of the Shin

come to Lairg, port of the mail-cars that cruise into far corners of this

county. The southern land, whose name tells how it was once counted part

of nakeder Caithness, has truly northern features of mountains and open

moors, lakes, "waters," "straths," and the "kyles" of its coast, those

deep narrow sounds taking their Gaelic name from the same root as Calais.

Three of its five sides are washed by the sea. The interior is chiefly

given up to deer and sheep, with here and there an oasis of moorland farm,

rescued from the heather as Holland from salt water, and only by ceaseless

industry held against Nature's encroachments. Too much of the land,

indeed, makes "a wilderness of brown and ragged moorland," whose

"monotonous features" are "masses of wet rock and dark russet heather,

black swamps, low and bare hills, and now and again the grey glimmer of a

stream or tarn "among heights" dulled with hurrying showers and glittering

out again to the sun."

The fish of its inland waters is one of Sutherland's

richest harvests. Its lakes are legion; one large parish alone is said to

contain hundreds of sheets; and the coming and going of anglers keeps up

the good roads and fair inns of a thinly-populated region, from which have

been swept away the traces of homes made desolate by the "Sutherland

evictions." Loch Shin, running half across the county from Lairg, is the

longest lake, about which man has waged feeble war with the sternness of

Nature ; but the wildest scene is Loch Assynt, near the west coast,

tapering among a group of grand mountains such as the Sutherlandshire Ben

More and the three-peaked mass of Quinaig. This remote nook seems

neglected by authors, yet a picturesque novelist might here find material

for a second Legend of Montrose, whose last adventure brought him

to be captured by Macleod of Assynt and confined in the Castle of Ardvreck.

As for the features of the west coast, behind which rise so wildly

weather-worn crags above glacier-planed glens and fiords, like those of

Norway on a smaller scale, they are thus summed up by Mr. John Sinclair in

his Scenes and Stories of the North of Scotland :—

"The Gaelic word 'Assynt' is a compound and signifies

'out and in.' If so, like almost all place-names in the Highlands, it is

most fitting and felicitous. Indeed it applies admirably, not only to the

district so called, but to the entire west coast of Sutherland from the

borders of Ross-shire to Cape Wrath itself. Looking, for instance, at the

map, we can still see in the endless contortions of the shore, as we used

to do when children, the figures and profiles of men and beasts—not one of

them in any degree like to any other. There are brows flat and high on the

headlands; eyes large and small in the lochs and tarns; noses Roman,

Grecian, retroussé, on the rocky capes; bay-mouths wide and narrow,

open and shut, drooping in sadness, curving upward in joy; chins which are

impudent, and chins which are retiring; cheeks smooth and furrowed, shaven

and bearded; and in all these you can clearly see, if you have any

discernment at all, grumpy grandfathers and grinning fools, laughing

children and scolding

The Isles of Loch Maree, Ross-Shire

dominies, gaping crocodiles and snarling monkeys,

weeping maids and wistful lovers. The surface of the country inland from

the shore is extremely varied, rugged, and wild, but full of interest and

charm for healthy and buoyant natures. If you believe, as I for one do,

that in order to see the beauties and taste the sweets of land and water

there is needed not only sight but insight, which is something far

more and better, you will find at every turn of the highway new

matter of surprise and admiration. Island-studded bays like Badcall,

picturesque retreats like Scourie; deeply indented lochs like Laxford, the

'Fiord of salmon'; distant views of a mountain-chain of peaks; long

successions of rocky knolls crowned with brushwood and heather—these are a

few of the elements which go to make up the panorama between Assynt

and the Kyle of Durness. When at length you look down over the brindled

cliffs of Cape Wrath ; when you behold its rugged masses of God-made

masonry; when you hear the thunder-throb of the waves in its vaulted

caverns; when you gaze to south and west and north over the hungry heaving

sea, you can but look and marvel and adore."

The north coast, with its Cave of Smoo and its Kyles of

Durness and of Tongue, is also grandly broken. The east shore, along which

the railway runs to Helmsdale, is rather a strip of fields and woods. In

the southeast corner lies Dornoch, which enjoys the distinction of being

the smallest county town in the kingdom, literally a village, with a

restored Cathedral as proof of city dignity, and on the site of its

Episcopal palace a prison that has been closed for want of custom among

the honest Highlanders. There has been little crime here since the last

witch was burned on British soil in 1722 at Dornoch. What brings strangers

to Dornoch, now that it has a railway branch, is its golf-links, extending

for thousands of acres on the seashore; and this far-northern understudy

of St. Andrews offers a remarkably good autumn climate, often mild up till

Christmas. Not much bigger is Golspie, with its sea-girt pile of Dunrobin,

seat of the ducal family that, owning most of Sutherland, and having

incorporated the title and estate of Cromarty as well as the English

peerages of Stafford and Gower, can hold up its head as the largest

landowner in Britain. With a thousand or so people of its own, Golspie has

a good hotel, from which strangers may visit the Dunrobin Glen and

waterfall, the traces of gold-working that once promised to pay in this

neighbourhood, and Ben Bhraggie conspicuously crowned by Chantrey's statue

of the first Duke of Sutherland.

Above Helmsdale, the Ord ridge makes the Caithness

frontier, round the end of which winds what is literally a highroad into

our northernmost county, described by Pennant as more terrible than the

Penmaenmawr track that used to be the bugbear of travellers to Ireland.

The road has been improved, but the railway is here forced away from the

sea, seeking an entry into Caithness farther inland. The southern part of

this county is still Highland, where the train runs on miles and miles

over unbroken stretches of heather ; then farther north these fall away

into a windy expanse of hollows and ridges, in which Nature would seem to

have come short of material for ending off our island with picturesque

effect; the central part has even been called the most forlorn wilderness

in Britain. Caithness, like other countrysides, has been "improved" in our

time; but still it shows wide, cheerless prospects of bog and waste, with

peat stacks more frequent than trees, and scattered, turf-walled houses

having their thatch bound on by straw ropes and weighted down by stones to

keep them from being blown away. Verses signed by the well-known initials,

"J. S. B.," set in a frame of honour at John o' Groat's House, describe

the bareness and bleakness of these poor fields, fenced by

Flagstones and slates in a row

Where hedges are frightened to grow;

and

Shrubs in the flap of the breeze,

Sweating to make themselves trees.

The most flourishing production of Caithness appears to

be the flagstones, layers of mud and fish bones pressed together ages ago,

which its quarries send forth to pave more genial regions. Its waters,

too, grow a valuable crop, as one may know who has ever seen the

multitudinous herring-fishing fleet set sail from Wick in the long summer

twilight. Angling can be had in a chain of some dozen lochs drained by the

Thurso river that runs through the county from south to north, at the

mouth of which over 2500 salmon were once netted in one haul. In the

south, if heather were edible, the folk should be fat; and below darkly

naked cones, we find glens such as Berriedale, in parts rich as well as

romantic, like a miniature Switzerland of which Morven is the Matterhorn.

Here again we have a duodecimo edition of Highlands and

Lowlands bound together. In the north-east the people are tall and sturdy,

with plain marks of Scandinavian origin, like their sters and

dales. On the south and west rather, we find clans bearing such names

as Mackay, Sutherland, Keith, and Gunn, the last certainly a Norse tribe

who can wear only an adopted tartan. Most illustrious of all were the

Sinclairs, that held the now dwindled Earldom of Caithness, one of those

Norman families settling themselves so masterfully all over Scotland. From

this farthest point of the kingdom, hundreds of them followed their Earl

to Flodden, and hardly one came back to tell the tale of that "Black

Monday," since when, it is said, no Sinclair will cross the Ord ridge on a

Monday. Another sore loss fell on the clan a century later, when a certain

Colonel Sinclair, heedless of what foreign enlistment regulations had then

taken shape, led a regiment of his clan to serve Gustavus Adolphus against

Norway, but, attacked by Norwegian peasants in a narrow gorge, more than

half of them were crushed beneath rocks hurled down from above, as

the French soldiers in Tyrol, or the Turks in defiles of the Kurdish

Dersim. The monument on the spot records the death of fourteen hundred

kindly Scots, which appears an exaggeration; but it is said that not a

score escaped with their lives. Many other grim and gory tales might be

told of this race, as some are in Mr. John Sinclair's book above

mentioned. The shells of castles fringing these shores have as often as

not had a Sinclair lord at one period or other, like Castle Sinclair,

almost crumbled away, while the older Girnigo, on to which it was built,

still stoutly defies the weather. Today the most outstanding branch of the

family is that of Thurso, first distinguished in a new field by Sir John

Sinclair's Statistical Account of Scotland, and by his improvements

in the county; then by the author of Holiday House, and by more

than one dignitary of the English Church. This family is notable for

stature as well as

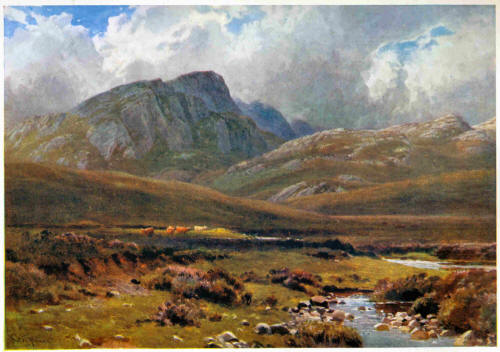

Moor and Mountain, Ross-shire

wisdom. I forget whether it was Catherine Sinclair's

father or brother who was said to have three dozen feet of daughters ; and

when he put down a new pavement— probably from his own quarries—opposite

his house in Edinburgh, it was readily nicknamed the "Giant's Causeway."

The main branch of the Sinclairs, whose titles at one time, says Sir

Walter, might have wearied a herald when they were not so rich as many an

English yeoman, is represented near Edinburgh by the ruins of Rosslyn

Castle and the monuments of that beautiful chapel—

Where Rosslyn's chiefs uncoffined lie

Each baron for a sable shroud

Sheathed in his iron panoply.

The railway, forking for the only Caithness towns, Wick

and Thurso, with their ports Pulteneytown and Scrabster, does not give a

fair view of the county. Its most impressive features, as at our other

Land's End, are to be looked for in its rim of brown cliffs, tight-packed

layers of flagstones, their faces "etched out in alternate lines of

cornice and frieze," here dappled by hardy vegetation, there alive with

clamorous sea-fowl. Like the granite, slate, and serpentine edges of

Cornwall, these sandstone rocks have been carved by wind and water into

boldest shapes of capes and bays, dark caverns, funnels, overhanging

shelves and gables, swirling "pots" and foaming reefs, isolated stacks

lashed by every tide, broken teeth bored and filled by every storm, and

the deep chasms here called geos, that sometimes lead down to

beaches rich in fine and rare shells, for one, "John o' Groat's Buckie,"

akin to the cowries of the tropics. In the damp crevices, also, grow rare

herbs such as that "Holy Grass" found by Robert Dick of Thurso, one of Mr.

Smiles's "discoveries" in the species of self-helped naturalists. More

truly than of Cornwall, it may be said that Caithness seldom grows wood

enough to make a coffin. Where Cornwall comes short of Caithness is in the

numerous castles, not all of them left to decay, that on the verge of

those northern precipices might often be confounded with Nature's own

ruins. It was only about the beginning of the eighteenth century that such

strongholds could be deserted for snugger mansions. Here, in 1680, was the

scene of our last private war, when the head of the Breadalbane Campbells

invaded Caithness with a small army, that overcame the Sinclairs, it is

said, by the wily stratagem of causing to be stranded on their coast a

ship freighted with whisky to drown the enemy's prudence and resolution.

Traces of older inhabitants are very frequent in

Caithness, its moors thickly strewn with hut circles, standing stones,

tumuli, and those curious underground excavations known as "Picts'

Houses," which appear to have been dwellings rather than burial-places.

One usual feature of such burrows is the cells and passages fitting a

smaller race than our noble selves, who must crawl on hands and knees in

grimy explorations not likely to be undertaken by the general tourist.

Hence there is reason to suppose that Scotland and other countries have

been inhabited by a stunted race of aborigines, like the dwarfish Ainos of

Yesso or the pygmies who turn up in various parts of Africa. Mr. David

MacRitchie, an antiquary who has paid special attention to so-called

Pictish remains, is doughty champion of a theory which connects the dimly

historic Picts or Pechts and the legendary Fians with the whole fabulous

family of fairies, elves, goblins, brownies, pixies, trolls, or what not,

who are represented as dwarfish and subterranean, issuing forth from their

retreats to hold varied relations of service or mischief with ordinary

men. The name of the Fians, belonging to Ireland as well as to the

Scottish Highlands, and fitly represented in the dark doings of Fenians,

may point to Finland, where small Laplanders still exist in flesh and

blood. The "good people," who long haunted Highland and Lowland glens,—but

it seems they cannot abide the scratching of steel pens or the squeaking

of slate pencils,— were apt to be tiny, of retiring habits, and in the way

of disappearing underground. So the fairies may have been real enough, for

all the scorn of that " self-styled science of the so-called nineteenth

century." Scott, who seems well disposed to the theory, tells us of

stunted, servile clans, such as the M'Couls, who were hereditary

Gibeonites to the Stewarts of Appin. In our own time Hebridean herds have

been found encamped inside beehive hillocks of turf such as opened to take

in the captives of fairy adventure. As for the objection that such beings

sometimes appeared as giants rather than dwarfs, it will be remembered how

a similar transformation came quite easy to Alice in Wonderland, how

omne ignotum pro magnifies is very apt to hold true in a misty

climate, and how visions of the spiritual in this country have often had

an origin disturbing to the senses—

Wi' tippenny we'll fear nae evil,

Wi' usquebaugh we'll face the devil.

But neither Mr. MacRitchie, in his Fians, Fairies,

and Picts and other writings, nor any of his

brother ethnologists, has much to tell us about John o' Groat, whose house

is the shrine of so many cyclists, wheeling piously from the Land's End, a

road of more than nine hundred miles at the shortest, through hundreds of

villages, scores of towns, and dozens of cities or places of fame. All

that way they come to see a low grassy mound and a flagstaff in front of

an hotel, a mile or two west from the pointed stacks of Duncansbay Head.

The story goes that this John was a Dutchman by descent, whose family,

split into eight branches, kept up meeting for an annual feast; then to

avoid squabblings for precedence, John hit on the idea of an octagonal

table in an eight-sided house, with eight doors and eight windows, in

which, let us trust, his kinsmen were not at sixes and sevens. Here we may

have some hint of such a contest for chieftainship as is not unknown among

Highland clans, else the folk-lorists must find this a hard text to

expound. Three, seven, and nine are all mystic numbers; five is time-honoured

in the East, as four in the Western world; two and ten have a practical

importance; six bears with it a sense of satisfaction, as do a dozen or a

score; thirteen and fourteen fit themselves to legend and superstition ;

even four-and-twenty blackbirds have been sagely interpreted as the hours

of the day and night ; but what can one say of eight in tale or history?

It might take a mathematician to make a myth here. Maybe the points of the

compass, doubled for the sake of emphasis, are at the bottom of it.

Perhaps there is some political allusion to James VI.'s Octavian board of

administrators. Or may some printer, short of copy, not

Crags near Poolewe, Ross-shire

have tried his hand at composing an octavo legend?

Possibly the story is more or less true, in which the Scotticised Dutchman

is further stated to have flourished as owner of a ferry to the Orkneys.

The suggestion that his fare was a groat must give way before the fact of

Groat being apparently a real Dutch name. Nor is it "past dispute" that

here geese are bred from barnacles, as asserted by sundry authors, among

them that tourist of Cromwell's time, Richard Franck, who seems to have

made his way so far, and gives us much quaint information about divinity,

scenery, and fishing, spoilt by a most affected style, by slap-dash

spelling of names, and by an evident "scunner" at his model Izaak Walton.

One thing seems certain, that John o' Groat was a

humbug if he gave out this non-existent house of his for the northernmost

point of our mainland, as stiff-kneed cyclists fondly reckon. That honour

properly belongs to Dunnet Head, the lofty line of red cliffs stretching

to the east of Thurso Bay, hollowed out by billows that shake the

lighthouse on the farthest point, from which one looks to the Orkneys over

the "still vexed" Pentland Firth. I wonder if that modern John o' Groat be

still to the fore, who some twenty years ago was presented with a

testimonial for his constancy in carrying across the mail during the

lifetime of a generation. He belonged to a school of ancient mariners who

had the knack of smelling their way about the sea, whereas our modern

Nelsons, it seems, don't know where they are till they have gone down into

their cabin and worked out a sum. I once crossed with this "skeely

skipper," and was much struck by his method of navigation. A thick fog

came on half-way across a tide that races at ten miles an hour ; then to

clear his inner light, he had up a glass of grog, through which he took

frequent observations. Every now and again he stopped the engines and

bawled out into the fog without any response; but when at last a muffled

hail came back, we were within a hundred yards of Scrabster Pier. On

another occasion, he is said to have hit it off still more closely,

carrying away the pier-head as a proof of his straight-steered course.

But here we must turn back, lest a darkless summer day

tempt us to cross to Orkney, and on to the much-battered Shetlands by the

stepping-stone of the Fair Isle, whose name, like that of the foreign

Faroe Isles, denotes not beauty but sheep. This muggy and windy

archipelago, indeed, is hardly Scottish ground, but an ex-Danish

possession, held in pledge by us for a princess's dowry that seems like to

be paid on the Greek Calends. Its people indignantly decline to be called

Scotchmen. And though our Thule has grand and fine features of its own,

too often wrapped in fog, they are hardly such as go to make up the

character of Bonnie Scotland.