|

Perth, the central city of Scotland, whose name has

been so flourishingly transplanted to the antipodes, is a very ancient

place. Not to insist on fond derivation from a Roman Bertha, there

seems to have been a Roman station on the Tay, probably at the confluence

of the Almond ; and curious antiquarians have found cause for confessing

to Pontius Pilate as perhaps born in the county, a reproach softened by

the consideration of his father being little better than a Roman exciseman.

The alias of St. Johnston Perth got from its patron saint, who came

to be so scurvily handled at the Reformation. At this date it was the only

walled city of Scotland. Before this, it had been intermittently the

Stuart capital in such a sense as the residence of its Negus is for

Abyssinia; and farther back Tayside was the seat of the Alpine kingdom

that succeeded a Pictish power. Now sunk in relative importance, Perth

makes the central knot of Scottish railway travelling; so on the Eve of

St. Grouse its palatial station becomes one of the busiest spots in the

kingdom, though the main platform is a third of a mile long. To the

stay-at-home public it may perhaps be best known by an industry that

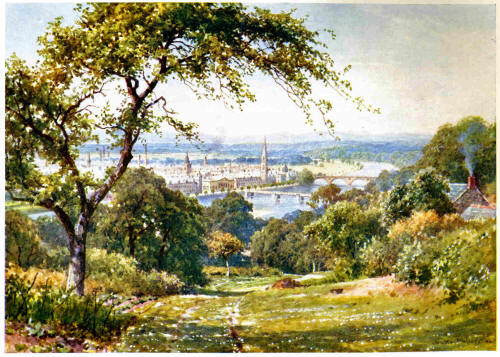

Perth from the Slopes of Kinnoul Hill

has given rise to the proverb "See Perth and dye"

one which might have darker significance in days when this low site

depended for drainage on the floods of the Tay flushing its cellars and

cesspools. But its own citizens are brought up to believe that no Naples

of them all has so much right to the title of the "Fair City."

Legend tells how Roman soldiers gaining a prospect of

the Tay from the heights south of Perth, exclaimed on its North Inch as

another Campus Martius; but later visitors have not always shared the

local admiration. One modern Italian traveller, Signor Piovanelli, after

wandering two or three hours about the Perth streets, took away an

impression of dull melancholy ; but then he began with an unsatisfactory

experience at the Refreshment Room. An else conscientious French tourist

explains the bustle of Perth station as its being the rendezvous of the

inhabitants seeking distraction from their triste life. These be

ignorant calumnies. At least our northern York is a typical Scottish town,

well displaying the strata of its development. In quite recent years it

has been much transmogrified by a new thoroughfare, fittingly named Scott

Street, which, running from near the station right through the city, has

altered its centre of gravity. The old High Street and South Street, with

their "vennels" and "closes," lead transversely from Scott Street to the

river, cut at the other end by George Street and John Street, which had

supplanted them as main lines of business. "Where are the shops?" I was

once asked by a bewildered party of country excursionists, wandering

unedified about the vicinity of the station. In those days one had to send

them across the city to the streets parallel with the river; but now Scott

Street has attracted the Post Office, the Theatre and the Free Library,

and bids fair to become the Strand or the Regent Street of the Fair City,

fringed by such a display of latter-day villas as attests the prosperity

of its business quarters.

Fragments of mediaeval antiquity also must be sought

for towards the river. Off John Street stands the old Cathedral, in the

practical Scottish manner shared into three places of worship, once

containing dozens of altars, among which an impudent schoolboy threw the

first image-breaking stone that spread such a ripple of icono-clasm

through the shrines of Scotland. Close by, on the river bank, the Gaol

occupies the site of Gowrie House, where James VI. had his mysterious or

mythical escape from treason. The Parliament House, too, has vanished, its

memory preserved by the name of a "close," the Scottish equivalent for

alley. The citizens have lately adopted a traditional "Fair Maid's" house

as their official lion, to which indicators point the way from all over

the city. This, whatever the higher criticism may say of its claims, has

been well restored as a specimen of a solid burgher's home in those days

when Simon the Glover was so vexed by the vagaries of his Highland

apprentice and by the roistering suitors of his daughter. Since then,

Perth has not wanted Fair Maids; but in our time the title has sometimes

had a satiric tang as implying what the French stigmatise as une rosse.

Simon, as we know, lived close to the royal lodging,

which, after the destruction of the castle, was wont to be thriftily taken

in the great monastery of Blackfriars, now represented only by the names

of a house and a street. In it were enacted stirring scenes of history as

well as of fiction, its darkest tragedy the murder of James I. on a

February night of 1437. Handsome, brave, a scholar and poet, with the

advantage of an involuntary English education, in quieter times this king

might have shown himself the best of the Stuarts. He had the welfare of

the people at heart, and on his return from the captivity in which he

spent his boyhood, tried to bring some degree of order among the lawless

feuds of his barons, using against them indeed high-handed and crooked

means that were the statecraft of the age. Thus he roused fell enemies who

were able to take him unawares, though the story goes that, like Alexander

and Caesar, he had warning from an uncredited seer. Betrayed by false

courtiers, he was retiring to bed when the monastery rang with the tramp

and cries of the fierce Highlandmen seeking his blood. While the queen and

her ladies tried to defend the door, Catherine Douglas giving her broken

arm, says the legend, as a bar, James tore up the flooring and let himself

down into a drain which he had, unluckily, blocked up a few days before,

since in it his tennis balls got lost. There he was discovered by the

conspirators, and after a desperate struggle their leader, Sir Thomas

Graham, stabbed him to death. Not a minute too soon, for already the good

burghers were roused to the rescue, and the regicides had some ado to spur

off to the Highlands, safe only for a time, the principal criminals being

taken for tortures that horrified even their cruel contemporaries.

From the windings of the Blackfriars quarter, one

emerges by what was the North Port, upon Perth's famous Inch, bordered by

erections that a generation ago were the modest West End of the city—Athole

Place, the Crescent, Rose Terrace, and Barossa Place. At the foot of the

Inch, by the river, stands a tall obelisk in honour of the 90th Regiment,

the "Perthshire Volunteers," now amalgamated with the Cameronians; and

near it the customary statue of Prince Albert, one of the first

inaugurated by Queen Victoria, who then insisted on knighting the Lord

Provost of the city, a worthy grocer, much to his discontent, and, if all

tales be true, to his loss in business. Perth, as becomes the ex-capital,

has a Lord Provost, who cannot meet the Lord Provost of Glasgow without

raising sore points of precedence. Invested with special powers when Perth

was a royal residence, its magistrates were not persons to be trifled

with, as an English officer found early in the eighteenth century. This

mettlesome spark, quartered here, had fatally stabbed a dancing-master who

stood in the way of troublesome attentions to one of his pupils. The same

day, tradition has it, the slaughterer was seized, tried, and hanged under

the old law of "red-hand," then put in force for the last time. An

ornament to the story is that the criminal's brother commanded a ship of

war in the Firth of Forth, over which was the way to Edinburgh, and that

he long kept watch for a chance of capturing some Perth bailie on whom to

take revenge. These were the good old times.

By the bridge at the foot of the North Inch, a

pretentious classical structure, marking the era of Provost Marshall whom

it commemorates, rears its dome above a Museum of Antiquities such as

becomes an ancient city. This faces the end of Tay Street, the pleasant

riverside boulevard between the North and South Inches,

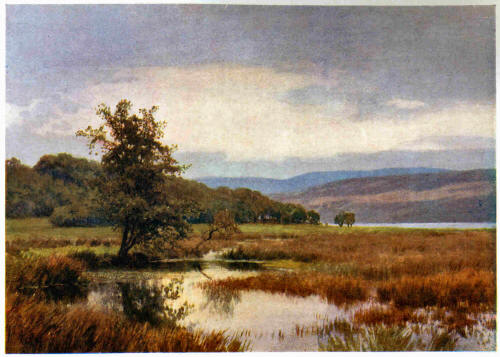

Ben A' An, Corner of Loch Katrine, Perthshire

towards the farther end of which a newer Museum

contains a remarkable natural history collection. At its corner of South

Street are the County Buildings, adorned with portraits of local worthies,

and at the end of High Street, the City Buildings with windows

illustrating Perth's history. Perth has now two bridges and everything

handsome about it—besides the Dundee railway bridge with its footway from

the South Inch. The central bridge is only three or four years old, but

here stood one washed away in 1621, since when the citizens had long to

depend on what is now the old bridge below the North Inch.

This bridge leads over into the transpontine suburb,

above which, on the slopes of Kinnoul Hill, the rank and fashion of the

city have inclined to seek "eligible building sites," Scotticé, "feuing

plots." The banks of the river, too, on this side have long been bordered

by villas and cottages of gentility; but about "Bridge End" there is still

a fragment of the humbler suburb that has had more than one famous

sojourner in our time. Here, in a house now distinguished by a tablet, and

afterwards in Rose Terrace opposite, John Ruskin spent bits of his

childhood with an aunt, wife of the tanner whose unsavoury business had

the credit of keeping the cholera away from Bridge End. That amateur of

beauty, for his part, has nothing but good to say of Perth : he remembers

with pleasure the precipices of Kinnoul, the swirling pools of the

"Goddess-river," even the humble "Lead," in which other less gifted

children have found "a treasure of flowing diamond," now covered up to

belie his vision of its defilement; and his lifelong impression was that

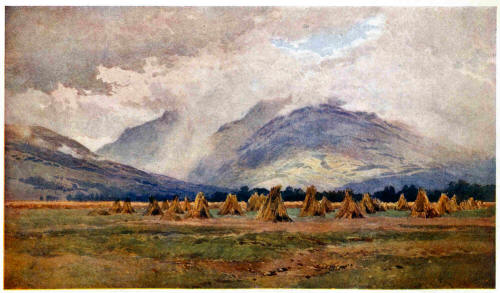

"Scottish sheaves are more golden than are bound in other lands, and that

no harvests elsewhere visible to human eyes are so like the 'corn of

heaven' as those of Strath Tay and Strath-Earn." Yet youthful gladness

turned to pain, when through his connection with Perth Ruskin came to make

that ill-matched marriage with its fairest maid, afterwards known as Lady

Millais. Their brief union he passes over in silence in his else most

communicative reminiscences; and the writer were indiscreet indeed who

should revive rumours spun round a case of hopeless incompatibility. One

misty legend, probably untrue, declares him, for certain reasons, to have

vowed never to enter the house in which her family lived, that Bowerswell

mansion, a little up the hill, where a crystal spring had often arrested

his childish attention. He did enter the house once, to be married,

according to the custom of the bride's Presbyterian Church: hinc illae

lacrimae, according to the legend.

Like that great prose-poet, the reader's humble

servant, without being able to boast himself a native of Perth, spent part

of his youth here and has pleasant memories that tempt him, too, to

be garrulous. I have no recollection of seeing Ruskin at Perth, but I well

remember Millais in the prime of manly beauty. In the early days of his

fame he lived much with his wife's family at Bowerswell; and several of

the children he then painted so charmingly were playmates of mine, who

would come to our Christmas parties in the picturesque costumes he had

been putting on canvas. For some reason or other, he never proposed to

immortalise my features; but I have boyish memories of him that seem to

hint at the two sides of his art. My sister sat for one of his most famous

pictures, on which, in the capacity of escort to his child model, I had

the unappreciated privilege of seeing him at work. What struck a little

Philistine like me was how the painter paid no attention to a call to

lunch, working away in such a furor of industry as I could

sympathise with only if mischief were in question. Someone brought him a

plate of soup and a glass of wine, which he hastily swallowed on his

knees, and again flung himself into his absorbing task. My internal

reflection was that in thus despising his meals this man showed such sense

as Macfarlane's geese who, as Scott records, loved their play better than

their meat. But a quite different behaviour on another occasion excited

stronger disapproval of the future P.R.A. in my schoolboy mind. When out

shooting with my father one hot day, I took him to a little moorland farm

where the people would offer us a glass of milk. Millais rather scornfully

asked if they had no cream. They brought him a tumblerful, the whole yield

for the day probably, and he tossed if off with a "Das ist kleine Gabe!"

air that set me criticising the artistic temperament. It was a fixed

notion with young Scots that all English people were greedy: "Set roasted

beef and pudding on the opposite side o' the pit o' Tophet, and an

Englishman will make a spang at it! " exclaimed the goodwife of Aberfoyle.

Thus we give back the southron's sneer for our frugal poverty. Our old

Adam might welcome the good things of life that fairly came our way; but

we schooled each other in a Spartan point of honour that forbade too frank

enjoyment. Millais was born very far south; and there are those who say

that he might have been a still greater painter, had he shown less taste

for the cream of life.

From Bowerswell, an artist had not far to go for scenes

of beauty. The road past the house, winding up to a Roman Catholic

monastery built since those days, leads on into the woods of Kinnoul Hill,

which is to Perth what Arthur's Seat is to Edinburgh. No tourist should,

as many do, neglect to take the shady climb through those woods,

suggesting the scenes of a tamed German "Wald." At the farther side one

comes out on the edge of a grand crag, the view from which has been

compared to the Rhine valley, and to carry out this similitude, a mock

ruin crowns the adjacent cliff. We have here turned our backs on the

Grampians so finely seen from the Perth slope of the hill, and are looking

down upon the Tay as it bends eastward between this spur of the Sidlaws

and the wooded outposts of the Ochils opposite, then, swollen by the Earn,

opens out into its Firth in the Carse of Gowrie, dotted with snug villages

and noble seats such as the Castle of Kinfauns among the woods at our

feet, a scene most lovely when

The sun was setting on the Tay,

The blue hills melting into grey;

The mavis and the blackbird's lay

Were sweetly heard in Gowrie.

The Gowrie earldom, once so powerful in Perth, has

disappeared from its life; but the title is still familiar as covering one

of those districts of a Scottish county that bear enduring by-names, like

the Devonshire South Hams or the Welsh Vale of Glamorgan. To a native ear,

the scene is half suggested by the word Carse,

Loch Vennachar, Perthshire

implying a stretch of rich lowland along a riverside,

whereas Strath is the more broken and extensive valley of a river that has

its upper course in some wilder Glen or tiny Den, the Dean of so

many southern villages. The course of the Tay from Perth to Dundee, below

Kinnoul, ceases to be romantic while remaining beautiful in a more sedate

and stately fashion as it flows between its receding walls of wooded

heights, underneath which the "Carles of the Carse" had once such an ill

name as Goldsmith's rude Carinthian boor, but so many a "Lass of Gowrie"

has shown a softer heart—

She whiles did smile and whiles did greet;

The blush and tear were on her cheek.

There are various versions of this ballad, whose tune

makes the Perth local anthem ; but they all tell the same old tale and

often told, with that most hackneyed of ends—

The old folks syne gave their consent;

And then unto Mass-John we went;

Who tied us to our hearts' content,

Me and the Lass o' Gowrie.

Many a stranger comes and goes at Perth without

guessing what charming prospects may be sought out on its environing

heights. But half an hour's stroll through the streets must make him aware

of those Inches that prompt a hoary jest concerning the size of the Fair

City. The North and South Inches, between which it lies, properly islands,

green flats beside the Tay, are in their humble way its Hyde Park and

Regent Park. The South Inch, close below the station, is the less

extensive, once the grounds of a great Carthusian

monastery, then site of a strong fort built by Cromwell, now notable

mainly for the avenue through which the road from Edinburgh comes in over

it, and for the wharf at its side that forms a port for small vessels and

excursion steamers plying by leave of the tide. On the landward side,

beyond the station, Perth is spreading itself up the broomy slopes of

Craigie Hill, which still offers pleasant rambles. Beyond the farther end

stands a gloomy building once well known to evil-doers as the General

Prison for Scotland ; but of late years its character has undergone some

change; and I am not sure how far the old story may still keep its point

that represents an inmate set loose from these walls, when hailed by a

friendly wayfarer as "honest man," giving back glumly "None of your dry

remarks!"

A more cheerful sight is the golf links on Moncrieff

Island, above which crosses the railway to Dundee. This neighbour has long

surpassed Perth, grown on jute and linen to be the third city of Scotland,

its name perhaps most familiar through the marmalade which used to be

manufactured, I understand, in the Channel Islands, when wicked wit

declared its maker to have a contract for sweeping out the Dundee theatre.

Northern undergraduates at Oxford and Cambridge are believed to have

spread to southern breakfasts the use of this confection in the form so

well known now that its materials are so cheap. The name has a Greek

ancestry, and the thing seems to have come to us as quince-preserve,

through the Portuguese marmelo, in time transferred and restricted

to another fruit. Oranges, indeed, could not have been as plentiful as

blackberries in Britain, when the Euphuist Lyly compared life without love

to a meal without marmalade.

Such a twenty-miles digression from the South Inch

implies how little there is to say about it. Now let us take a dander up

the larger North Inch, Perth's Campus Martius, at once promenade,

race-course, review ground, grazing common, washing green, golf links,

cricket-field, and area for unfenced football games in which, summer and

winter, young Scots learn betimes to earn gate-money for English clubs.

Opposite the Perth Academy appears to have been the arena where that early

professional, Hal o' the Wynd, played up so well in the deadly match by

which the Clan Kay and the Clan Chattan enacted the less authentic tragedy

of the Kilkenny cats. This spacious playground is now edged by a neat

walk, which makes the constitutional round of sedate citizens, who on the

safe riverside have the spectacle of pleasure boating against the

difficulties of a strong stream and shallow rapids, and of the pulling of

salmon nets in the season. Here a barelegged laddie, with the rudest

tackle, has been known to hook a 30-lb. fish, holding on to the monster

for two hours till some men helped him out with his fortune. The salmon of

the Tay, reared in the Stormontfield Ponds above Perth, are famous for

size, a weight of over 70 lbs. being not unknown; and cavillers on other

streams cannot belittle its bigger fish by the sneer of "bigger liars

there!" The keeping of fish in ice, and railway communications, have much

enhanced the price, to the astonished of a Highland laird who in a London

tavern ordered a steak for himself and a "salmon for Donald" without

guessing that his henchman's meal must be paid for in gold as his own in

silver. The old story of masters contracting not to feed their servants on

salmon more than twice a week, is told, by Ruskin for one, of Tay-side as

of other river-lands. But so masterful are the demands of London now, that

salmon may sometimes be dearer on the banks of the Tay than in the glutted

metropolitan market. The Tay has another treasure, for now and then

valuable pearls have been fished out of it by boys who, in a dry summer,

can wade across its shallows just above the old bridge. A very different

sight might be seen here when the river was frozen across and roughened by

a jam of miniature icebergs.

Half-way up the town side of the Inch, where a few

trees dotted across it mark its old limits, extended more than a century

ago, stands the now restored mansion of Balhousie, which used to be known

as Bushy by that curious trick of contraction, more common in

Scottish than in English names, that drove a bewildered foreigner to

complain of our pronouncing as Marchbanks what we spelt as

Cholmondeley. But one notes how in Scotland as in England, the

tendency is to restore such words to their full sound, as in this case.

Near the station in Perth is Pomarium Street, marking the orchard of the

old Carthusian monastery, or, as some have held, the outskirt of the Roman

City. Consule Planco, I knew it only as the Pow; but out of

curiosity I lately tried this abbreviation in vain on a postman and on a

telegraph boy of the present generation. Methven, near Perth, was always

pronounced Meffen; Henry VIII. spells it Muffyn; as Ruthven

was and perhaps still is Riven. The station of Milngavie is no

longer

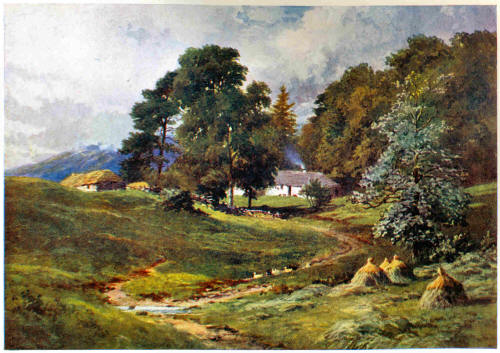

A Croft near Dalmally, Argyllshire

proclaimed by railway porters as Millguy, and

the place Claverhouse—no hero indeed at spelling—spells Ruglen,

tends to assume its full dignity of Rutherglen, as Cirencester or

Abergavenny lose their old contractions in this generation's mouth. Many

other examples might be given of a change, with which, I fancy, railway

porters have much to do; but one of the best authorities on such matters,

Dr. H. Bradley, puts it down to what he calls half-education, setting up

spelling as an idol. As for the altered pronunciation of Scottish

family names, that seems often to come from English blundering, modestly

adopted by their owners. Balfour, to take a distinguished example, was

Balfour, till the trick of southern speech shifted back the accent. Forbes

is still vernacularly a dissyllable in the Forbes country, as in

Marmion, and in the old schoolboy saw about General 4 B's, who marched

his 4 C's, etc. Dalziels and Menzies must have long given up in despair

the attempt to get their names properly pronounced in the south as Déél

and Meengus. The family known at home as Jimmyson become

now content to have made a noise in the world as Jameson. But some such

changes have been long in progress. It was "bloody Mackengie" whom

audacious boys dared to come out of his grave in Greyfriars' Churchyard;

and if we go far enough back we find the name of this persecutor written

Mackennich. In the good old times every gentleman had his own spelling, as

what for no? There is a deed, and not a very ancient one, drawn up by

certain forebears of mine, in which, among them, they spell their name

five different ways. In general, it may be remembered, the z that

makes such a stumbling-block to strangers in so many Scottish names, is to

be taken as a y. When we have such real enigmas as Colquhoun and

Kirkcudbright to boggle over, the wonder is that Milton should make any

ado at Gordon or "Galasp," by which he probably meant Gillespie.

Nearly opposite Balhousie, which has suggested this

digression, across the Tay, peeps out the house of Spring-lands, which

reminds me how Perth has been the cradle of a sect. The Sandemans of

Springlands in my youth exhibited some marked religious leanings, but none

of them, I think, followed the doctrine of their ancestor. The sect in

question was founded in the days of early methodism by John Glass, a

Scottish clergyman; but his son-in-law, Robert Sandeman, proved so much

the Paul of the new faith by preaching it as far as America, that there,

as in England, the body is known as Sandemanians, while in Scotland they

still sometimes bear the original name Glassites. Their most famous member

was Michael Faraday, who preached in the London meeting-house. Its

doctrine had, like Plymouth Brethrenism, a strange attraction for old

Indian officers, who, cut off from home influences, repelled by

surrounding heathenism, and their brains perhaps a little addled by the

sun, have often been led to read odd meanings into revelations and

prophecies, studied late in life. There used to be a detachment of retired

veterans encamped about Perth as headquarters of their Bethel, whose wives

and children, in some cases, attended the Episcopal Chapel. A peculiarity

of their belief was an absolute horror of being present at any alien

worship, even family prayers, as I could show from some striking

instances. This must have borne hard on soldier converts, who, in the

army, are allowed a choice of only three forms of worship. "No fancy

religions in the service," growled the sergeant to a recruit who professed

himself a Seventh Day Baptist: "fall in with the Roman Catholics!" Another

note of the Sandemanians was an unwillingness to communicate their views,

what even seemed a resentful-of inquiry by outsiders. Disraeli excused a

similar trait in the Jews by the dry remark, "The House of Lords does not

seek converts." I once in the innocent confidence of youth asked a

Glassite leader to enlighten me as to their faith, and was snubbed with a

short "The doors are open." But I never heard of any stranger trusting

himself within the doors of that meeting-house. Report gave out a

love-feast as a main function, from which the sect got "kailites" as a

nickname. The kiss of peace, it was understood, went round; and ribald

jesters represented the presiding official as obliged to exhort, "Dinna

pass over the auld wife!" This much one can truly say of the congregation,

that they were kind and helpful to each other, a Glassite in distress

being unknown in the Fair City, where they had adherents in all classes.

As for their spiritual exclusiveness, against that reproach may be set the

old story of the "burgher " lass who, having once attended an

"anti-burgher" service with her lad, was rebuked by her own kirk-session

for the sin of "promiscuous hearing."

Above the Inch comes the less trim space called the "Whins,"

where lucky caddies glean lost golf balls in its patches of scrub and in

pools formed by the highest flowing of the tide from the Firth. With this

ends the public pleasure-ground but the walk may be prolonged along the

elevated bank of the river, above the sward that makes the town

bathing-place, and brown pools that Ruskin might have found perilous as

well as picturesque, but as he speaks of himself as keeping company with

his girl cousin, not to speak of the fear of his careful mother, we may

suppose that he made no rash excursions into the water. One deep swirl

within a miniature promontory is aptly known as the "Pen and Ink"; then

higher up a shallow creek encloses the " Woody Island," no island to

bare-legged laddies who here play Robinson Crusoe.

The opposite bank shows a lordly park with timber that

should bring a blush to the cheek of Dr. Johnson's ghost, concealing the

castellated Scone Palace, seat of its Hereditary Keeper, Lord Mansfield,

who has another enviable home beside Hampstead Heath. Little remains of

the old royal Castle and Abbey of Scone; the Stone of Destiny, that

ancient palladium, fabled pillow of Jacob's vision of the angels, on which

the Scottish kings were crowned, has been in Westminster Abbey since

Edward I.'s invasion. The modern mansion contains some relics of Queen

Mary and her son, but its owners do not encourage visitors. An eminence

near at hand is known by the curious name of the Boot Hill, tradition

making it formed by the earth which nobles after a coronation emptied out

of their boots, so stuffed that each proud baron might feel the

satisfaction of standing on his own ground!

Half-a-dozen miles farther up the river, on this side,

one is free to seek the top of Dunsinnan Hill for what is believed to have

been the site of Macbeth's Castle, and for a fine prospect of the

Grampians with Birnam Wood in the foreground. Shakespeare, and the legend

he followed,

Wet Harvest Time near Dalmally, Argyllshire

make no account of the fact that a considerable river

guarded Dunsinnan from hostile advance of its distant neighbour. Yet a

parish minister of these parts has convinced himself that the author of

Macbeth must have known the neighbourhood. One conjecture is that he

visited Perth with a far-strolling troop of actors. "You will say next

that Shakespeare was Scotch!" exclaimed a scornful southron to a Scot who

seemed too patriotic; and the cautious answer was, "Weel, his abeelity

would warrant the supposeetion." As for Macbeth and his good lady, it is

time that some serious attempt were made to whitewash their characters, as

Renan has done for Jezebel, and Froude for Henry VIII. No doubt these two

worthies represented the good old Scottish party, strong on Disruption

principles and sternly set against the Anglican influences introduced

through Malcolm Canmore, in favour of whose family the southern poet shows

a natural bias. Did we know the whole truth, that gracious Duncan may have

had a scheme to serve the Macbeths as the Macdonalds of Glencoe were

served by their guests. The one thing clear in early Scottish history is

that the dagger played a greater part than the ballot box, and that

scandals in high life might sometimes be obscured by an eloquent advocate

on one side or other. Sir Walter does give some hints for a brief in

Macbeth's case, though in his Tales of a Grandfather he sets the

orthodox legend strutting with its "cocked hat and stick." Macbeth, as he

says, probably met Duncan in fair fight near Elgin; and the scene of his

own discomfiture appears to have been the Mar country rather than the Tay

valley.

But we are still strolling on the right bank of the Tay,

to be followed for a mile or two up to the mouth of the Almond, a pretty

walk, which few strangers find out for themselves. There is in Scotland a

want of the field paths which Hawthorne so much admired in England,

"wandering from stile to stile, along hedges and across broad fields, and

through wooded parks leading you to little hamlets of thatched cottages,

ancient, solitary farmhouses, picturesque old mills, streamlets, pools,

and all those quiet, secret, unexpected, yet strangely-familiar features

of English scenery that Tennyson shows us in his idylls and eclogues."

Every inch of tillable land is in the north more economically dealt with;

the farmer, struggling against a harsher climate, cannot afford to leave

shady hedges and winding paths; his fields are fenced by uncompromising

stone walls against a looser law of trespass. Embowered lanes, too, "for

whispering lovers made," are rarer in this land of practical farming. Here

it is rather on wild " banks and braes "of streams, unless where their

waters can be coined into silver as salmon-fishings, that lovers and poets

may ramble at will, shut out from the work-a-day world by thickets of

hawthorn, brier, woodbine, and other "weeds of glorious feature":—

The Muse, nae poet ever fand her

Till by himsel' he learned to wander

Adown some trotting burn's meander,

An' no think lang.

If any ill-advised stranger find the streets of the

Fair City dull, as would hardly be his lot on market-day, let him turn to

Kinnoul Hill for a noble scene, and to the Tay banks for a characteristic

one of broad fields and stately woods, backed by the ridge of the

Grampians a dozen miles away. For another sample of Scottish aspects he

might take the Edinburgh road across the South Inch, and over by Moncrieff

Hill to the Bridge of Earn, where he comes into the lower flats of

Strathearn, on which a tamed Highland stream winds sinuously to the Tay

between its craggy rim and the rounded ridge of the Ochils. The village

has a well-built air, due to the neighbourhood of Pitkaithly spa, that in

Scott's day was a local St. Ronan's, whose patrons lodged at the Bridge of

Earn, or even walked out from Perth, to take the waters, which before

breakfast, on the top of this exercise, must have had a notable effect in

certain cases. The original Spa in Belgium owed much of its credit to the

fact of its springs being a mile or two out of the town. Our forefathers'

ignorance of microbes seems to have been tempered by active habits: it was

more than a dozen miles Piscator and his friends had to trudge from

Tottenham before reaching their morning draught at Hoddesdon. As for

Pitkaithly, there is at present an attempt to resuscitate the use of its

waters, still dispensed near Kilgraston, a house founded by a Jamaica

planter, who had two such sons as General Sir Hope Grant and Sir Francis

Grant, P.R.A.

This part of Strathearn is a flat lowland plain, on

which, once in a way, I have seen a pack of foxhounds, whereas, in the

ruggeder mass of the county, as English squires must be scandalised to

learn—

Though space and law the stag we lend,

Ere hound we slip or bow we bend,

Whoever recked where, how, and when,

The treacherous fox is trapped or slain.

Where foxes are sometimes like wolves for size and

destructiveness, a Highland fox-hunter ranks with a ratcatcher. But Fife,

at hand over the Ochils, is a civilised region in which Reynard claims his

due observance. Near its border, still in Perthshire, is the sadly-decayed

town of Abernethy, whose Round Tower makes the only monument of the days

when it was a Pictish capital. Another seat of Pictish princes, not far

away, was at Forteviot, near the Kinnoul Earls' Dupplin Castle, where

Edward Balliol defeated the Regent Mar in a hot fight, before marching on

to Perth to be crowned for a time, when Scotland, like Brentford, had two

kings. If only for their natural amenities, these spots might well be

visited; yet to tourists they are unknown unless as way-stations

respectively on the rival North British and Caledonian railways from

Edinburgh to Perth. But to me each of their now obscure names is dearly

familiar, since the days when they were landmarks on my way back from

school, from which in those days one came back more gladly; and

Auchterarder, Forteviot, FORGANDENNY, made a crescendo of

joyful sounds, each hailing a stage nearer home. |