Like Somerset, claiming to be something more than a

mere shire, the county half fondly, half jestingly entitled a kingdom,

lies islanded between two firths, cut off from the world by the sea and

from the rest of Scotland by the Ochil ridges. The "Fifers" are thus

supposed to be a race apart; but it would be more like the truth to take

Fifeishness as the essence of Saxon Scotland. Fife is, in fact, an epitome

of the Lowlands, showing great stretches of practically prosaic farming,

others of grimy coal-field, with patches of moor, bog, and wind-blown

firs, here and there swelling into hill features, that in the abrupt

Lomonds attain almost mountain dignity in face of their Highland namesake,

sixty miles away. Open to cold sea winds, it nurses the hardy frames of "buirdly

chiels and clever hizzies"; and all the invigorating discipline of the

northern climate is understood to be concentrated in the East Neuk of

Fife, where a weakling like R. L. Stevenson might well sigh over the

"flaws of fine weather that we call our northern summer." It is in the

late autumn that this eastern coast is at its best of halcyon days. As we

have seen, the poet lived a little farther south who still laid himself

open to Tom Hood's reproach—

'Come, gentle spring, ethereal mildness come!'

O Thomson, void of rhyme as well as reason,

How could'st thou thus poor human nature hum—

There's no such season!

In the Antiquary's period, we know how Fife was

reached from Edinburgh by crossing the Firth at Queensferry, as old as

Malcolm Canmore's English consort, or by the longer sail from Leith to

Kinghorn, where Alexander III. broke his neck to Scotland's woe. A more

roundabout land route was via Stirling, chosen by prudent souls

like the old wife who, being advised to put her trust in Providence for

the passage, replied, "Na, na, sae lang as there's a brig at Stirling I'll

no fash Providence!" Lord Cockburn records how that conscientious divine,

Dr. John Erskine, feeling it his duty to vote in a Fife election, when too

infirm to bear the motion of boat or carriage, arranged to walk all the

way by Stirling, but was saved this fortnight's pilgrimage by the contest

being given up. Till the building of its Firth bridges, the North British

Railway's passengers had to tranship both in entering and leaving Fife, a

mild taste of adventure for small schoolboys. Now, as all the world knows,

the shores of Lothian are joined to Fife by that monumental Forth Bridge

that humps itself into view miles away. Then all the world has heard of

the unlucky Tay Bridge, graceful but treacherous serpent as it proved in

its first form, when one stormy Sabbath night it let a train be blown into

the sea. By these constructions the line has now a clear course on which

to race its Caledonian rival, either for Perth or Aberdeen. But

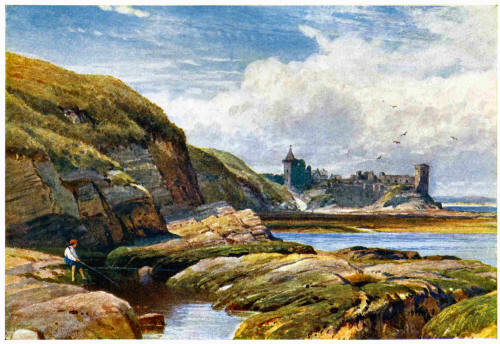

The Castle of St. Andrews, Fifeshire

there is no racing done on the cobweb of North British

branches woven to catch Fife-farers, at whose junctions, as a local

statistician has calculated, the average Fifer wastes one-seventh of his

life or thereabouts. Ladybank Junction, stranded on its moor, used to have

the name of a specially penitential waiting-place, which yet lent itself

to romantic account in one of those Tales from Blackwood.

The towns of Fife are many rather than much. Cupar, the

county seat, is still a quiet little place, whose Academy stands on the

site of a Macduff stronghold, recalling that Thane of Fife with whom the

Dukedom of our generation is connected only in title. "He that maun to

Cupar, maun to Cupar," says the proverb, but few strangers seem to risk

this vague condemnation. When James Ray passed through the town on his way

to Culloden, he has little to tell of it unless that he put up at the

"Cooper's Arms" which, more by token, was kept by the Widow Cooper. The

above proverb, by the way, seems to belong to Coupar-Angus, usually so

distinguished in spelling, and is transferred to its namesake by "Cupar-justice,"

a Fife version of the code honoured at Jedburgh. A Scotch cooper or couper

may not have to do with barrels, unless indirectly in the way of business,

but is also a chaffer or chapman, par excellence, of horses ; and

one would like to believe, if philologists did not shake their heads, that

these towns got their name as markets, like English Chippings and Cheaps.

In an out-of-the-way edge of the county, below the

Lomonds, lies Falkland, whose royal palace, restored by the late Marquis

of Bute, was the scene of that dubious tragedy enacted in the Fair Maid

of Perth, where the dissolute Duke of Rothesay is a little

white-washed to heighten the dramatic atrocity of his death. A

few miles behind Queensferry is Dunfermline, another place where kings

once sat "drinking the blood-red wine," now a thriving seat of linen

manufacture, among its mills and bleachfields containing choice fragments

of royal and ecclesiastical architecture, as well as modern adornments

given by its bounteous son Mr. Andrew Carnegie, native of the town where

Charles I. was born, and Robert Bruce buried beside Malcolm Canmore and

his queen. There are some fine modern monuments in the new church, which

adjoins the monastic old one, testifying stiffly to Presbyterian distrust

of Popish arts; and altogether Dunfermline is one of those places that

might well "delay the tourist."

But the largest congregation in Fife is that "long

town" of Kirkcaldy, flourishing on jute and linoleum since the days when

Carlyle and Irving were dominies here, the former a humane pedagogue,

though he scourged grownup dunces so unmercifully, while the bygone peace

of the place was often broken by the wailing of Irving's pupils under the

tawse with which he sought to drive them into unknown tongues. Kirkcaldy

has older historic memories; but somehow it is one of those Scottish towns

that, like Peebles and Paisley, lend their names to vulgar or comic

associations. Was it not a bailie of Kirkcaldy who said, "What wi' a' thae

schules and railways, ye canna' tell the dufference atween a Scotchman and

an Englishman noo-a-days!"

Let the above words be text for a sermon, to which I

invite seriously-minded readers, while the otherwise-minded may amuse

themselves by taking a daunder among the lions of Kirkcaldy. The subject

is Scottish Humour, which Englishmen are apt to rank with the snakes of

Iceland or the breeks of a Highlander. Foreigners do not make the same

mistake, as how can they when the best known English humorists are so

often Scotsmen or Irishmen? It is the pure John Bull whose notions of the

humorous are apt to be rather childish; so when he gets hold of a joke

like that about the surgical instrument, he runs about squibbing it in

everybody's face, and never seems to grow tired of such a smart saying,

nor cares to ask if there be any truth in it beyond the fact that one

people may not readily relish another's wit or wisdom.

The vulgar of all nations have a very rudimentary sense

of the comic, coarse enough in many Scotsmen who can appreciate no more

pointed repartee than—

The never a word had Dickie to say,

Sae he ran the lance through his fause bodie!

The characteristic form of English humour is more or

less good-natured chaff, bearing the same relation to keen raillery as a

bludgeon does to a rapier. A master of this fence was Dr. Johnson, who, if

his pistol missed fire, knocked you down with the butt end of it. Sydney

Smith's residence in Edinburgh should have given him a finer style, which

he turned to so unworthy use in mocking at Scottish "wut." As to the

distinction between wit and humour, I know of no better than that which

defines the one as a flash, the other as an atmosphere. It may be granted

that the Scottish nature does not coruscate in flashes. But what your

Sydney Smiths do not observe is that it develops a very high quality of

humour, which has self-criticism as its essence. Know thyself, has been

styled the acme of wisdom; and when the Scotsman's best stories come to be

analysed, the point of them appears to be a more or less conscious making

fun of his own faults and shortcomings, which is a wholesomer form of

intellectual exercise than that parrot-trick of nicknaming one's

neighbours. The bailie's boast above quoted is a characteristic instance

over which an Englishman may chuckle without seeing the true force of it.

All those hoary Punch jests as to "bang went saxpence," and so

forth, are good old home-made Scottish stories, which the southron brings

back with him from their native heath, and dresses them up for his own

taste with a spice of malice, then rejoices over the savoury dish which he

has prepared by seething poached kids in their mother's milk. Yet often

print fails to bring out the true gust that needs a Doric tongue for

sauce; and the Englishman who attempts any Scottish accent is apt to merit

their fate who ventured to meddle with the ark, not being of the tribe of

Judah. The effect of such a story depends as much on the actor as on the

words. To mention but one of many noted masters of this art, who that ever

spent an evening with the late Sir Daniel Macnee, President of the

Scottish Academy, could hold the legendary view of his countrymen's want

of fun? He had to be heard to be appreciated ; but, at the risk of

misrepresenting his gift, here is one of his anecdotes. He was travelling

with a talkative oil merchant who, after much boast of his own business,

began to rally the other on his want of communicativeness— "Come now, what

line are you in?"— "I'm in the oil trade too," confessed the painter,

whereupon his companion fell to pressing him for an order.— "We'll do

cheaper for you than any house in the trade!" At last, to get rid of his

persistency, Sir Daniel said, "I don't mind taking a gallon from you."—"A

gallon! Man, ye're in a sma' way!"

Perhaps this humour is a modern production, like

certain fruits cultivated in Scotland "with deeficulty." There were times,

indeed, when life here was no laughing matter. But even the sun-loving

vine is all the better for a touch of frost at its roots, and the best

wines are not those the most easily made. In contrast with other

home-brewed fun that soon goes flat, and with such cheap brands as "Joe

Miller," the vintage of Scottish humour, if not distinguished by

effervescing spurts of fancy, has body and character which only improve by

age, keeping well even when decanted, and giving a marked flavour when

mixed with less potent materials, into Punch, let us say. There is

also a dry quality thrown away on palates used to the public-house tap;

Ally Sloper, for instance, might not taste the womanthropy, as he would

call it, of that bachelor divine who began his discourse on the Ten

Virgins with "What strikes us here, my brethren, is the unusually large

proportion of wise Virgins." A good Scotch story, with the real

smack upon the tongue, bears to be told again, like an aphorism distilled

from the wisdom of generations. Sound humour is but the seamy side of

common-sense, for a sense of the incongruous degenerates into nonsense if

not shaped by a clear eye for the relation and proportion of things. If

the reader will consider the many specimens of Scottish humour now current

in England, or to be drawn from such treasuries as Dean Ramsay's ; and if

he will reflect on their weight and minting, he may understand the value

of this coinage in the national life.

The northern Attic salt abounds in one savour that

appears in a hundred stories like that of the preacher who, at Kirkcaldy

or elsewhere, apologised for his want of preparation: "I have been obliged

to say what the Lord put into my mouth, but next Sabbath I hope to come

better provided!" If there is any subject which the Scot takes seriously

it is religion, that yet makes the favourite theme of his jests. Revilers

have gone so far as to state that the incongruous elements of Scottish

humour are usually supplied by a minister and a whisky bottle. It is

certainly the case that a Scotsman relishes playing upon the edge of

sacred things, and that the pillars of his church will shake their sides

over stories which strike Englishmen as irreverent. But has not vigorous

faith often shown a tendency to overflow into backwaters of comicality, as

in the gargoyles of our cathedrals, the mediaeval parodies of church

rites, and the homely wit of Puritan preachers? There are some believers

who can afford a laugh now and then at their sturdy solemnities, others

who must keep hush lest a titter bring down their fane like a house of

cards. Familiarity with the language of the Bible counts for a good deal

in what seems the too free handling of it in the north. But note how the

irreverence of the Scot's humour is usefully directed against his own

tendency to fanaticism. It is only of late years, I think, that he has

taken to joking on the religious practices of his neighbours, whose

shortcomings once seemed too serious for joking. That

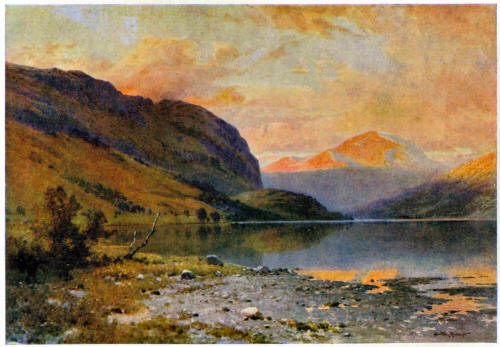

Loch Lubnaig, Perthshire

"one" of the servant girl who described the services at

Westminster Abbey as "an awful way of spending the Sabbath" may be taken

as a sign of growing charity. Yet, in the past, too, a Scotsman seldom

chuckled so heartily as over any rebuke to priestly pretension within his

own borders. Jenny Geddes's rough form of remonstrance with the dignitary

who would have read the mass in her lug was a practical form of Scotch

humour, that on such subjects is apt to have a good deal of hard earnest

in it. As for the Kirk's own ministers, the tyranny ascribed to them by

Buckle has long been tempered by stories at their expense. Buckle's famous

comparison of Spain and Scotland is vitiated by his leaving out of account

that natural sense of humour that has aided popular instruction in

counteracting superstition. Dean Ramsay ekes out Carlyle and other weighty

authors who explain how Irving found no depth of earth in Scotland for the

seeds of his wild enthusiasm, and why the tourist seeks in vain for

winking Madonnas at Kirkcaldy, long ago done with all relics and images

but the battered figureheads of her whalers.

Kirkcaldy's whalers now grow legendary, and strangers

beholding her shipping to-day, may take for a northern joke that this

ranks as the third Scottish port of entry ; but the fact is that a whole

string of Fife harbours are officially knotted together under its name, as

all North America was once tacked on to the manor of Greenwich, and every

British child born at sea belongs to the parish of Stepney. The coast-line

here is thick-set with little towns of business and pleasure, grimy coal

ports and odorous fishing havens, alternating with bathing beaches and

golf-links in the openings of the low cliffs. At the western edge has now

been taken in the old burgh Culross, pronounced in a manner that may

strike strangers as curious. Not far from the Forth Bridge is the

prettiest of Edinburgh seaside resorts, Aberdour, with its own ruins to

show, and the remains of an abbey on Inchcolm that shuts in its bay, and

behind it Lord Moray's mansion of Doni-bristle, part of which stands a

charred shell, burned down and rebuilt three times till its owner accepted

what seemed a decree of fate. Opposite Edinburgh, Burntisland's prosaic

features make a setting for the castle of Rossend, with its romantic

scandal about Queen Mary and Chastelard. Beyond Kirkcaldy come Leven and

Largo, trying to grow together about the statue of Alexander Selkirk; and

Largo House was home of a more ancient Fifeshire mariner, Andrew Wood, his

"Yellow Frigate" a sore thorn in England's side, as commemorated by a

novel of James Grant, who wrote so many once-so-popular romances of war.

Fife coast towns have a way of sorting themselves in couples. At the

corner of the bay overlooked by Largo Law, Elie and Earlsferry flourish

together as a family bathing place, behind which, at the pronunciation

of Kilconquhar the uninitiated may take a thousand guesses in vain.

Then we have Anstruther and Crail on Fifeness, that sharp point of the

East Neuk of Fife. Round this, at the mouth of the Eden, we come to St.

Andrews, "gem of the province."

Everybody has heard of St. Andrews, but only those who

have seen it understand its peculiar rank among seaside resorts. It is

distinguished by a certain quiet air, like some high-born spinster's,

accustomed to command respect, whose heirlooms of lace and jewellery put

her above any need of following the fashions. Her parvenu rivals must lay

themselves out to attract, must make the best of their advantages, must

ogle and flirt, and strain themselves to profit by the vogue of public

favour. St. Andrews does not display so much as an esplanade, standing

secure upon her sober dignity, a little dashed, indeed, of Saturday

afternoons by excursions from Dundee. Other sea-side places may be said to

flourish, but the word seems inappropriate in the case of this resort,

that yet thrives sedately, as how should she not with so many strings to

her bow? First of all she is a venerable University city, whose Mrs.

Bouncers ought to make a good thing of it with the students and the

sea-bathing visitors playing "Box and Cox" for them through the winter

session and the summer season. Then she is a Scottish Clifton or Brighton

of schools, recommended by the singular healthiness of the place. Unless

in the smart new quarter near the railway station, the dignified bearing

of an ancient town carries it over the flighty manners of a

watering-place. The only pier is a thing of use, where the wholesome smell

of seaweed mingles with a strong fishy flavour. No gilded pagoda of a

bandstand profanes the "Scores," that cliff road which your Margates would

have made into a formal promenade. A few bathing machines on the sands

alone hint at one side of the town's character. In one of the rocky coves

of the cliff is a Ladies' bathing place, which I can praise only by report

But the Step Rock, with its recent enclosure to catch the tide, is now

more than ever the best swimming place on the East Coast.

What first strikes one in St. Andrews is its union of

regularity and picturesqueness, and of a cheerful well-to-do present with

relics of a romantic past. Its airy thoroughfares, with their plain

solidity of modern Scottish architecture, form an effective setting for

bits of antiquity, such as the ivy-clad fragment of Blackfriars' Chapel,

and the Abbey wall, beneath which no professor cares to walk, lest then

should be fulfilled a prophecy that it is one day to fall upon the wisest

head in St. Andrews. The architectural treasures of this historic

cathedral city would alone be enough to make it a place of pilgrimage.

"You have here," says Carlyle, "the essence of all the antiquity of

Scotland in good and clean condition." Southron strangers will hardly

understand how these fragments of ecclesiasticism have become a nursery of

Protestant sentiment. A generation ago it was stated that but one solitary

Romanist could be found in the little city. Generations of Scottish

children, like myself, have been shown that gloomy dungeon at the bottom

of which once pined the victims of Giant Pope, a sight to fill us with

shuddering horror and hate of persecuting times ; but we were not told how

Protestants could persecute, too, while they knew not yet of what spirit

they were. What shades of grim romance haunt these crumbling walls, what

memories of Knox and Beaton, what dreams of the old Stuart days! I never

realised the power of their associations till one evening, on the Scores,

there sat down beside me two French tourists who had somehow strayed into

St. Andrews, and their light talk of boulevards, theatres, and such like,

seemed sacrilegious under the shadow of the Martyrs' Memorial.

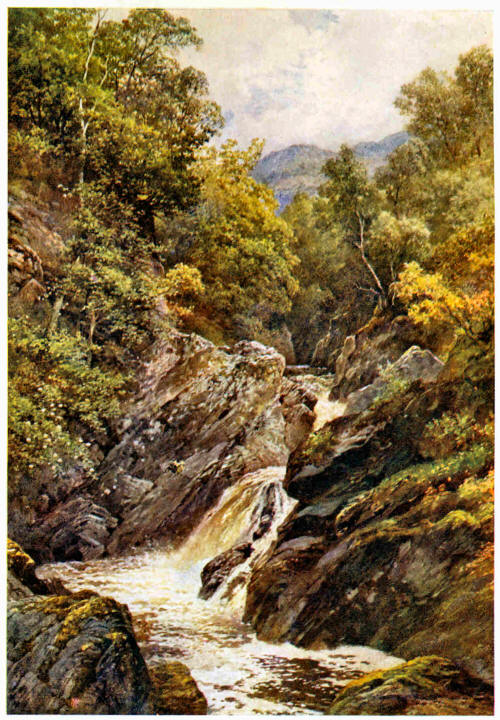

In Glenfinlas, Perthshire

I have an acquaintance with St. Andrews going back more

than half a century. My introduction to club life was at the club

here, then a cottage of two or three rooms, into which I was invited under

charge of my nurse, and treated to the refreshment of gingerbread snaps by

a member who seemed to me little short of a patriarch. In the scenery of

my childhood, nothing stands out more clearly and cheerfully than those

sandy green links dotted with red jackets and red flags, not to speak of

the red balls with which enthusiasts bid defiance to snow and ice. Nay,

another among my earliest reminiscences is of seeing the multitudinous

seas themselves incarnadined, when, for once, the golfers allowed their

attention to be drawn from their own hazards. A cry had been raised that a

lady was drowning; then every group of red jackets within hearing forgot

their balls, flung down their clubs, raced across the links, dashed into

the waves, and struggled emulously to the rescue. I think a caddie, after

all, was the fortunate youth who had the glory of achieving such an

adventure.

Since those days, when feather balls cost half-a-crown

and few profane foreigners had penetrated its mysteries, the Golf Club has

been transformed in a style becoming the chief temple of this Benares,

hard by a more modest "howff" for the "professionals" who are its

Brahmins, where little "caddies" swarm like the monkeys of an Indian

sanctuary. For golf is the idol of a cult that draws here many pilgrims

from far lands, now that, in the international commerce of amusement,

while barelegged little Macs take kindly to cricket, the time-honoured

Caledonian game spreads fast and far over England, over the world, indeed,

for on dusty Indian maidans good Scotsmen can be seen trying to

play the rounds of Zion in that strange land, and under the very Pyramids

a golf course is laid out, where the dust of Pharaohs may serve as a tee,

or a mummy pit prove the most provoking of bunkers. In the home of its

birth this pastime flourishes more than ever. Parties are given for golf

along with tea and tennis; schools begin to lay out their golf ground as

well as their football field; and at St. Andrews we have the Ladies'

Links, where many a masculine heart has been gently spooned or putted into

the hole of matrimony. Fair damsels may even be seen lifting and driving

in a "foursome," an innovation frowned at by some old stagers, who hardly

care to talk about the game till it is ended, and then can talk of nothing

else. "Tee, veniente die, tee, decedente—!" is the song of

St. Andrews, which asks for no more absorbing joy than a round in the

morning and a round in the evening. In the eyes of inveterate golfers, all

prospects are poor beside those links that make the Mecca, the Monte

Carlo, the Epsom of the royal game, so one is free to give up the

surrounding country as not much contributing to the attractions of the

place, many of whose visitors hardly care to stir beyond their beloved

arena, unless for a Sunday afternoon walk along the shore as far as that

curious freak of the elements known as the Spindle Rock.

Besides its devotion to the game where clubs are always

trumps, St. Andrews has in the last generation had an attraction for

celebrities in literature and science. The University staff, of course,

makes a permanent depot of intellect. The facile essayist A.K.H.B. was

long parish minister here, when the Episcopal bishop was a nephew of

Wordsworth, himself an author too well known to schoolboys. Here Robert

Chambers spent the evening of his days. Blackwood the publisher had a

house close at hand, where many famous authors have been guests. In the

vicinity, too, is Mount Melville, seat of Whyte-Melville, the novelist.

Not to mention living names, the late Mrs. Lynn Linton was a warm lover of

St. Andrews. It must have been well known to Mrs. Oliphant, more than one

of whose novels take this country for their scene.

Is it impertinent to say a word in praise of a writer,

too soon forgotten at circulating libraries, where she was but too

voluminously in evidence for the best part of her lifetime? Had she been

content with a flat in Grub Street, Mrs. Oliphant might now be better

remembered than by the mass of often hasty work for which her way of life

gave hostages to fortune and to publishers. Her novels often smell too

much of an Aladdin's lamp that had to be rubbed hard for copy; there is

awful example to money-making authorship in a middle period of them that

scared off readers for whom again she would rise to her early charm.

Defects she had, notably a curious warp of sympathy that led her to do

less than poetic justice to prodigal ne'er-do-weels; but her chief fault

was in writing too much, when at her best she was very good. Her best

known stories are those which deal with English life; yet she was not less

happy in describing her native Scotland, having an extraordinary insight

that set her at home in very varied scenes and classes of society. Few

writers are found in touch with so many phases of life. Even George Eliot,

sure as she is in portraying her Midland middle-class life, seems a little

depaysé when she strays among fine folk; and many a skilful

novelist might be mentioned who falls into convention or caricature as

soon as he gets out of his own familiar environment. But, after Sir

Walter, I doubt if there be any author who has given us such a varied

gallery of Scottish characters, high and low, divined with Scott's

sympathy and often drawn with Jane Austen's minute skill. Her servants and

farmers seem as natural as her baronets and ministers, all of them indeed

ordinary human beings, not the freaks and monsters of the overcharged art

that for the moment has thrown such work as hers into the shade.

Of her tales dealing with Fife, perhaps the best, at

least the longest, is "The Primrose Path," a beautiful idyll of this East

Neuk, its scene laid within a few miles of St. Andrews, evidently at

Leuchars, where such a noble Norman chancel is disgraced by the modern

meeting-house built on to it, and the old shell of Earl's Hall offered

itself as a fit setting for the drama of an innocent girl's heart, that at

the end shifts its stage to England. The hero, he that is to be made happy

after all, plays a somewhat colourless part in the background; but heroes

have license to be lay figures. The real protagonist, the imperfectly

villainous Rob Glen, seems to walk out of the canvas; and all the other

characters, from the high-bred, scholarly father to the love-sick servant

lass, are alive with humour and kindliness. As for the scenery, it is thus

that Mrs. Oliphant puts the East Neuk in its best point of view:—

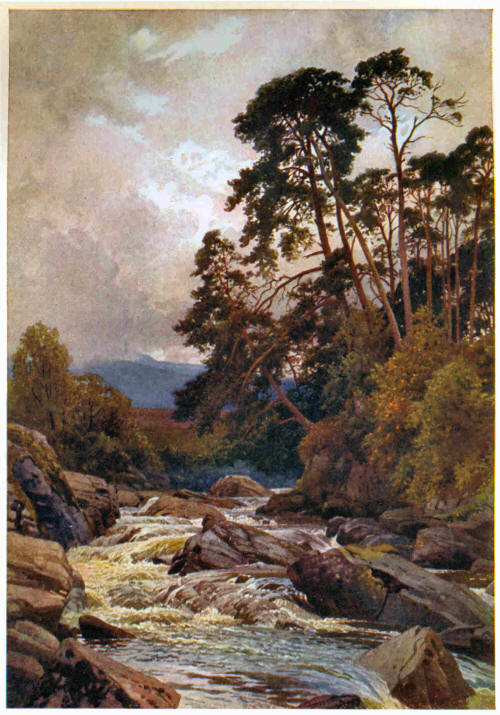

On the Dochart, Killin, Perthshire

"There does not seem much beauty to spare in the east

of Fife. Low hills, great breadths of level fields: the sea a great

expanse of blue or leaden grey, fringed with low reefs of dark rocks like

the teeth of some hungry monster, dangerous and grim without being

picturesque, without a ship to break its monotony. But yet with those

limitless breadths of sky and cloud, the wistful clearness and golden

after-glow, and all the varying blueness of the hills, it would have been

difficult to surpass the effect of the great amphitheatre of sea and land

of which this solitary grey old house formed the centre. The hill, behind

which the sun had set, is scarcely considerable enough to have a name; but

it threw up its outline against the wonderful greenness, blueness,

goldenness of the sky with a grandeur which would not have misbecome an

Alp. Underneath its shelter, grey and sweet, lay the soft levels of

Stratheden in all their varying hues of colour, green corn, and brown

earth, and red fields of clover, and dark belts of wood. Behind were the

two paps of the Lomonds, rising green against the clear serene: and on the

other side entwining lines of hills, with gleams of golden light breaking

through the mists, clearing here and there as far as the mysterious

Grampians, far off" under Highland skies. This was one side of the circle;

and the other was the sea, a sea still blue under the faint evening skies,

in which the young moon was rising ; the yellow sands of Forfarshire on

one hand, stretching downwards from the mouth of the Tay, the low brown

cliffs and green headlands bending away on the other towards Fifeness—and

the great bow of water reaching to the horizon between. Nearer the eye,

showing half against the slope of the coast, and half against the water,

rose St. Andrews on its cliff, the fine dark tower of the college church

poised over the little city, the jagged ruins of the castle marking the

outline, the cathedral rising majestically in naked pathos; and old St.

Rule, homely and weather-beaten, oldest venerable pilgrim of all, standing

strong and steady, at watch upon the younger centuries."

From the flattest part of Fife, let us turn to its

inland Highland side. The main North British line to Perth, after passing

a dreary coal-field, brings us suddenly beneath the bold swell of Benarty,

round which we come in view of the Lomonds with Loch Leven

sparkling at their foot. Here indeed we soon get into the small shire of

Kinross; but this may be taken as a dependency of the kingdom of Fife, its

lowlands also running on the west side into a miniature Highland region,

reached by the railway branch that from Loch Leven goes off to

Stirling by the Devon Valley and the Ochils, at the end of which

Clackmannan vies with Kinross as the Rutland of Scottish counties.

Loch Leven is celebrated for its breed of trout,

and for that grey tower half hidden by trees on an islet, which was poor

Mary Stuart's prison. The dourest Scotsman's heart has three soft spots,

the memory of Robert Burns, the romance of Prince Charlie, and the

misfortunes that seem to wash out the errors of that girl queen. This is

dubious ground, into which tons of paper and barrels of ink have been

thrown without filling up a quaking bog of controversy. I myself have

heard a distinguished scholar hissed off the most philosophic platform in

Scotland for throwing a doubt on Queen Mary's innocence, so I will say no

more than that her harshest historian, if shut up with her in Loch Leven

as page or squire, might have been tempted to steal the keys and take an

oar in the boat that bore her over those dark waters to brief freedom and

safety. Had Charles Edward only had the luck to get his head cut off in

solemn state, how much more gloriously dear might now be his memory!

As Scott points out, Fife was noted for a thick crop of

gentry, who were apt to be found on the side of the Queen Marys and Prince

Charlies, whereas its sturdy common folk rather favoured Whig principles.

Not far from Kinross the grey homespun of Scottish life is proclaimed by

one of those ugly obelisks that have so much commended themselves for the

expression of Protestant sentiment. At Gairney Bridge, on the Fife and

Kinross border, in 1733, four suspended ministers formed themselves into

the first Presbytery of the Original Secession Church, a most fissiparous

body which brought forth a brood of sects not yet altogether swallowed up

in the recent union of the Free and United Presbyterian churches. I am

bound to special interest in that foundation, for as a forebear of mine

appears riding away from the shores of Loch Leven in Queen Mary's train,

so one of those four seceders was my great-great-great-great (or

thereabouts) grandfather, Moncrieff of Culfargie, himself grandson of a

still remembered Covenanter. His spiritual descendants make a point of the

fact that being a small laird, he yet testified against the unpopular

system of patronage, and thus is taken to have been before his time. But

Plato amicus, etc., or as Sterne translates, "Dinah is my aunt, but

truth is my sister," and a closer examination reveals among the heads of

my forefather's testimony against the Church of Scotland a conscientious

protest in favour of executing witches and persecuting Roman Catholics, so

perhaps the less said about his views the better. A few years before, a

poor old wife, rubbing her hands in crazy delight at the blaze, had been

burned as a witch for the last time in Scotland; and the "moderate"

ministers were now content to ignore an imaginary crime which a few years

later became wiped out of the statute-book.

The ancestral shade should know how filial piety urged

me, perhaps alone in this generation, to perform the rite of

reading his works, which indeed want such "go" and "snap" as are admired

by congregations who "have lost the art of listening to two hours'

sermons. "He was truly a painful and earnest preacher, in one volume of

whose discourses I note this mark of wide-mindedness, that it is entitled

"England's Alarm," whereas other old Scottish divines seem rather

to treat the neighbour country as beyond hope of alarming. His

brother-in-law, Clerk of Penicuik, characterises Culfargie as "a very

sober, good man, except he should carry his very religious whims so far as

to be very uneasy to everybody about him." It is recorded of him that he

prayed from his pulpit for the Hanoverian King in face of the

Pretender's bristling soldiery, like that other stout Whig divine whose

petition ran, "As for this young man who has come among us seeking an

earthly crown, may it please Thee to bestow upon him a heavenly one!"

Loyalty to the same line was less frankly shown by a very different member

of our clan, Margaret Moncrieff, a name little renowned on this side the

Atlantic, while she figures in more than one American book as the

"Beautiful Spy." Being shut up among rebels in New York, when the

besieging Engineers were commanded by her father Colonel Moncrieff, she

got leave to send him little presents, among them flower-paintings on

velvet, beneath which were traced plans of the American works. The device

being discovered, it might have gone hard with her but for Yankee

chivalry, that expelled that artful hussy unhurt, in the end to bring no

honour upon her name, if all tales of her be true.

The ancestral worthy whose memory has led me into a

digression, lived and laboured in Strathearn, to which from Kinross we

pass by Glenfarg, no Highland glen but a fine gulf of greenery with

stream, road, and railway winding side by side through its banks and

knolls, that called forth Queen Victoria's warm admiration on her first

visit to Scotland. At the other end of this Ochil gorge we are welcomed to

Perthshire by the wooded crags of Moncrieff Hill, round which the Earn

bends to the Tay; then some dozen miles behind, rises the edge of the true

Highlands, where "to the north-west a sea of mountains rolls away to Cape

Wrath in wave after wave of gneiss, schist, quartzite, granite, and other

crystalline masses."