|

Beyond Edinburgh, perhaps the best known town in

Scotland is Stirling, which hordes of pilgrims pass in the round trip of a

single day through the famous Trossachs District, displaying such a finely

mixed assortment of Scottish scenery, lochs, woods, and mountains

that like giants stand

To sentinel enchanted land.

Stirling, on the edge of the Highlands, played a

central part, even long after the Scottish kings had been drawn down to

the rich fields of Lothian and the Merse. From the rock on which the

Castle stands, only less boldly than that of Edinburgh, one looks over the

Links of Forth, making such sinuous meanderings upon its Carse, and across

to the Ochil Hills that border Fife ; then from another point of view

appear the rugged Bens among which Roderick Dhu had his strongholds. Not

fair prospects alone are tourists' attraction to Stirling. The palace of

James V., the houses of great nobles like Argyll and Mar, the execution

place of the last Roman Catholic Archbishop of Scotland, the memorials of

Protestant martyrs, the proud monuments of Bruce and Wallace, the ruins of

Cambuskenneth Abbey, with its royal sepulchre, all show this region the

heart of mediaeval Scottish history. While Edinburgh grew to be recognised

as the capital, Stirling Castle was the birthplace and the favourite

residence of several among the James Stuarts that came to such an uneasy

crown in boyhood ; sometimes it was their prison or their school of

sanguinary politics, when possession of the royal person counted as ace in

the game played by truculently treacherous nobles. It has the distinction

of being the last British castle to stand a siege, raised in 1746 by the

Duke of Cumberland, when, as his panegyrical historian says, "in the Space

of one single Week, his Royal Highness quitted the Court of the King his

Father, put himself at the head of his Troops in Scotland, and saw

the Enemy flying with Precipitation before him, so that it may be said

that his progress was like Lightning, the rebels fled at the flash,

fearing the Thunder that was to follow." Its ramparts look down on

Scotland's dearest battlefields, that where Wallace ensnared the invader

at the Old Bridge, and that of Bannockburn, when Bruce turned the flower

of English chivalry to dust and to gold, for, as the latest historian

says, "it rained ransoms" in Scotland after this profitable victory.

One may speculate what might have been the fate of the

United Kingdom had Bannockburn ended otherwise. Would the barons of the

north have found a master in Edward III.? Would the Plantagenets, with

Scotland to back them, have made good their conquest of France? Would the

stern reformers across the Tweed have suffered the Tudors to shape and

re-shape the Church as they

Stirling Castle from The King's Knot

did? Would the Scottish adventurers who once kept their

swords sharp as soldiers of fortune all over Europe, have sooner found a

career in forcing themselves to the front of British society? This much

seems clear, that there has been a woeful waste of ill-blood before a

union that came about after all, in the way of peace. Yet are we so made

that the most philosophic Scot, even fresh from a course of John Stuart

Mill or Herbert Spencer, cannot look down upon these battle-grounds

without a throb in his heart. It was Bannockburn that made us a nation,

poor but free to be ourselves. Then, since we did not always come off so

well in our battles with England, naturally we make much of the points won

in a doubtful game. When I was at school there came among us perfervid

young Scots an English boy, before whom, we agreed, it would be courteous

and kind not to mention Bannockburn. Yet in the end some itching tongue

let slip this moving name, but without ruffling our new comrade's pride.

It turned out that he complacently took Bannockburn to have been an

English victory ; at all events, one more or less made no great matter to

his thinking. Englishmen take their own national trophies so much for

granted, that they are apt to forget the susceptibilities of other

peoples. Such a one was rebuked by a coachman driving him over the field

of Bannockburn. "You Scotch are always boasting of your country, but when

you come south you are in no hurry to get back again." With thumb pointed

to the ground, the Scot made stern answer: "There was thirty thousand o'

you cam north, and no mahny o' them went back again!" There are other

battlefields about Stirling, of which Scotland has no such title to be

proud, as that of Falkirk, where Wallace brought his renown to a falling

market and Prince Charles Edward had but half a victory; that of

Sauchieburn, where James III. was foully slain; and that of Sheriffmuir,

the Culloden of 1715.

Let us hang a little longer upon the Castle ramparts to

take a bird's-eye view of the stirring story that often came to centre

round this rock. Over Highland mountain and Lowland strath the clouds lift

away, giving here and there a doubtful glimpse of Scots from Ireland,

Celts from who knows how far, Britons of Strathclyde, and dim Picts of the

east, each such a wild race as "slew the slayer and shall himself be

slain," among whom intrude Roman legions and Norse pirates, the former

falling back from their thistly conquest, the latter settling themselves

firmly on the coasts. Out of this welter, as out of the Heptarchy in the

south, emerges a more or less dominant kingdom seated on the Tay. While

the power of the Scots seems to have gone under, their name floats at the

top, so as to christen the new nation, that on the south side, from the

wide bounds of Northumbria, takes in a stable element destined to be the

cement of the whole.

The next act shows the struggle of a partly Saxonised

people against the Anglo-Norman kings and their claims to feudal

superiority. The curtain rises on a sensational melodrama of confused

alarms and excursions, where the ill-drilled Celtic supernumeraries at the

back of the stage often fall to fighting like wild cats among themselves,

while the mail-clad barons prance now on one side and now on the other, as

the scenes shift about a border-line almost rubbed out by the crossing and

recrossing of

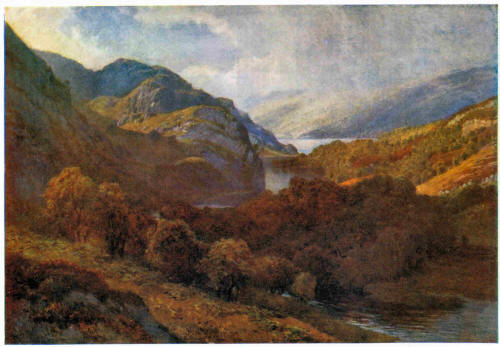

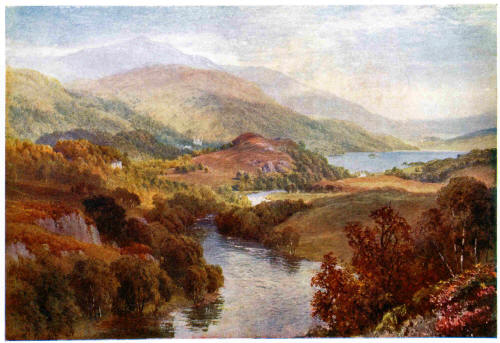

The Outflow of Loch Katrine, Perthshire

armies. The heroes of the most thrilling tableaux are

Wallace and Bruce ; and the loudest applause hails the culminating blaze

of lime-light on Bannockburn.

The wars of Independence are not yet at an end, but the

Scots people have learned more or less firmly to stand together, and their

chiefs, when not led astray by feud and treachery, begin to enter into the

spirit of the piece, in which France now takes a leading part. But

Banquo's ill-fortune dogs the line not yet fully consecrated by

misfortune. Over the stage passes that woeful procession of boy kings,

most of them cut off before they had learned to rule, each leaving his son

to be in turn kidnapped and tutored by fierce nobles to whom John Knox

might well have preached on the text "Woe to thee, O land, when thy king

is a child!" more profitably than he denounced that "monstrous regiment of

women." This act culminates in the Reformation, when for a generation

Scotland is not clear whether to cry "Unhand me, villain!" to France, or

to England, the two powers that at her side play Codlin and Short in a

tragic mask.

When James VI. had posted off to his richer

inheritance, we might expect an idyllic transformation scene of peace out

of pain. But the Scot has no turn for peace. Is it the mists and east

winds that set such a keen edge on his temper? When not at loyal war, he

is robbing and raiding his neighbours, as if to keep his hand in; and if

no strife be stirring at home, he hires himself out as a professional

fighter or football player over foreign countries and counties, for pelf

indeed, but also for the zest of the game. And now that Scotland has no

longer its wonted national exercise of defending itself against England,

it developed at home that notable taste for spiritual combat; so the next

act has for its main interest a controversy as to what things were

Caesar's, throughout which the hard-headed and hot-hearted theologians of

the north made fitful efforts to be loyal to Caesar, who, on his part,

gave them little cause for loyalty.

With the Revolution Settlement and the Act of Union the

stage appears cleared for a happy denouement, which, indeed, but for

episodes of rebellion and vulgar grudges on both sides, comes on at length

as the two rivals learn how after all they are not hero and villain, but

long-lost brothers, the one rich and proud but generous, the other poor

and honest. Already, before the world's footlights, we see them fallen

into each other's arms, blessed by nature and fortune, to the music of

"Rule, Britannia," amid the cheers of a crowd of colonies, though foreign

spectators may shrug their shoulders and twirl their moustaches when

invited to applaud.

But may there not be an epilogue to the sensational

acts of Scottish history? As Saxondom overcame the plaided and kilted

clans, is not Scotland in turn destined to overlie the rest of the island?

Here we approach a delicate subject of consideration. In this enlightened

age when, as a great Scotsman says, "the Torch of Science has now been

brandished and borne about with more or less effect for five thousand

years and upwards," the truly philosophic mind should be capable of rising

above the pettiness of national prejudice. Only foolish and uninstructed

persons can cling to the belief that their peculiar community, large or

small, is necessarily identified with the highest excellences of creation.

Wise

In the Heart of the Trossachs, Perthshire

men agree to recognise that as a poor vanity which

winks fondly at the halo consecrating its own faults, while blind to the

plainest merits of its neighbours. Excesses, defects, and compensations

must be everywhere recognised and allowed for, then at last we can take a

calm and exact account of human nature in its different manifestations

regarded by the light of impartial candour. And when in such a judicious

spirit we come to survey mankind from China to Peru, there can surely be

little doubt as to the due place of Scots in the broken clan of McAdam.

The above edifying principles were earnestly enforced

upon me by a French savant with whom I once travelled in the Desert

of Sahara, who yet almost foamed at the mouth if one pointed the moral

with a Prussian helmet-spike. Hitherto, alas! international

characterisations have been coarse work, usually touched with a spice of

malice Every parish flatters itself by locating Gotham just over its

boundary, as any county may have some unkind reproach against its

neighbours, Wiltshire moon-rakers, Hampshire hogs, or what not; and

nations, too, bandy satirical epithets, like those of a certain poet—

France is the land of sober common-sense,

And Spain of intellectual eminence.

In Russia there are no such things as chains;

Supreme at Rome enlightened reason reigns.

Unbounded liberty is Austria's boast,

And iron Prussia is as free—almost.

America, that stationary clime,

Boasts of tradition and the olden time.

England, the versatile and gay,

Rejoices in theatrical display.

The sons of Scotia are impulsive, rash,

Infirm of purpose, prodigal of cash.

But Paddy------

But, indeed, the rest is too scandalous for publication.

The most marked feature of the Scottish national

character is perhaps an engaging modesty that forbids me to dwell on the

achievements of a small country's thin population, who have written so

many names so widely over the world. But it must be admitted how the King

of Great Britain sits on his throne in virtue of the Scottish blood that

exalted a "wee bit German lairdie." Our men of light and leading are

naturally Scotsmen, the leaders of both parties in the House of Commons,

for instance. Since Disraeli—himself sprung from the Chosen People of the

old Dispensation—Lord Salisbury was our only Premier not a Scotsman. Both

the present Archbishops of the Anglican Church come from Presbyterian

Scotland. The heads of other professions in England usually are or ought

to be Scotsmen. The United States Constitution seems to require an

amendment permitting the President to be a born Scot; but such names as

Adams, Polk, Scott, Grant, McClellan, and McKinley have their significance

in the history of that country, while in Canada, of course, Mac has come

to mean much what Pharaoh did in Egypt. It is believed that no Scotsman

has as yet been Pope; but there appears a sad falling away in the Catholic

Church since its earliest Fathers were well known as sound Presbyterians.

The first man mentioned in the Bible was certainly a Scot, though English

jealousy seeks to disguise him as James I. Your "beggarly Scot" has the

Apostles as accomplices in what Englishmen look on as his worst sin, a

vice of

Brig O' Turk and Ben Venue, Perthshire

poverty which, in the fulness of time, he begins to

live down. Both Major and Minor Prophets deal with their Ahabs and

Jezebels much in the tone of John Knox. A legend, not lightly to be

despised, makes our ancestress Scota, Pharaoh's daughter; but I do not

insist on a possible descent from the lost Tribes of Israel. Noah is

recorded as the first Covenanter. Cain and Abel appear to have started the

feud of Highlander and Lowlander. Father Adam is certainly understood to

have worn the kilt. The Royal Scots claim to have furnished the guard over

the Garden of Eden, in which case unpleasing questions are suggested as to

the duties of the Black Watch at that epoch. The name of Eden was at one

time held to fix the site of Paradise in the East Neuk of Fife; but the

higher criticism inclines to Glasgow Green. In the south of Lanark,

indeed, are four streams that have yielded gold; but they compass a

country more abounding in lead, and the climate seems not congenial to

fruit trees. "I confess, my brethren," said the controversial divine,

"that there is a difficulty here ; but let us look it boldly in the face,

and pass on."

The antiquities of Stirling contrast with the modern

trimness of its neighbour, the Bridge of Allan, lying at the foot of the

Ochils two or three miles off, a Leamington to the Scottish Warwick, the

tramway between them passing the hill on which, to humble southron

tourists, Professor Blackie and other ardent patriots reared that tall

Wallace Monument whose interior makes a Walhalla of memorials to eminent

Scotsmen like Carlyle and Gladstone. Bridge of Allan is a place of mills

and bleach works, and of resort for its Spa of saline water, recommended,

too, by its repute for a mild spring climate, rare in the north. The

"Bridge," which we have so often in Scottish place-names, points to a time

when bridges were not matters of course; as in the Highlands we shall find

"Boats" recording a more backward stage of ferries. This bridge spans the

wooded "banks of Allan Water," up which a pleasant path leads one to

Dunblane, with the Ochil moorlands for its background.

Dunblane is notable for one of the few Gothic

cathedrals still used in Scotland as a parish church. Sympathetically

restored, it has even become the scene of forms of worship which

scandalised true-blue Presbyterians, while on the other hand I once came

across an Anglican lady much shocked to find how "actually there was a

Presbyterian service going on!" Carved screen, stalls, and communion table

make ornaments seldom seen in the bareness of a northern kirk, this one

admirable in its proportions and mouldings, if without the elaborate

decoration of Melrose. It has a valuable legacy in the library of a divine

well known in both countries, the tolerant Archbishop Leighton.

Among Scotsmen, Dunblane enjoys a modest repute as a

place of villeggiatura; to tourists it is perhaps best known as

junction of the Caledonian line to Oban, which brings them to Callander, a

few miles from the Trossachs. This line at first follows the course of the

Teith, "daughter of three mighty lakes," past Doune Castle, not Burns's

"Bonnie Doon," but an imposing monument of feudal struggles and crimes,

that has housed many a royal guest, if not, as one of its parish ministers

gravely declares for unquestionable, Fitz-James himself on the night

before his adventurous chase. So late as 1745,

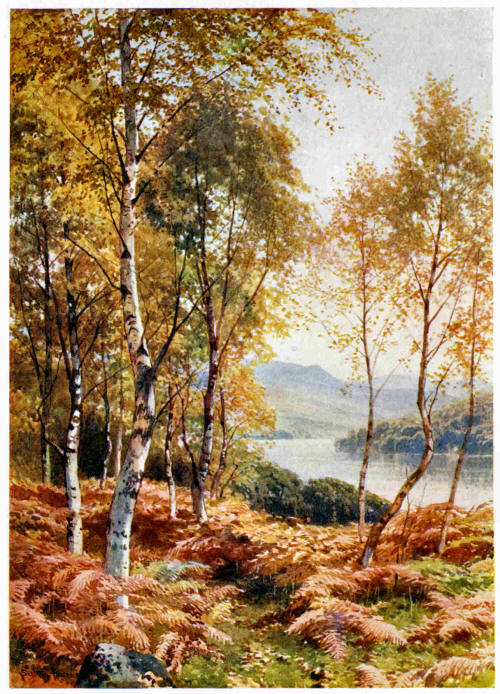

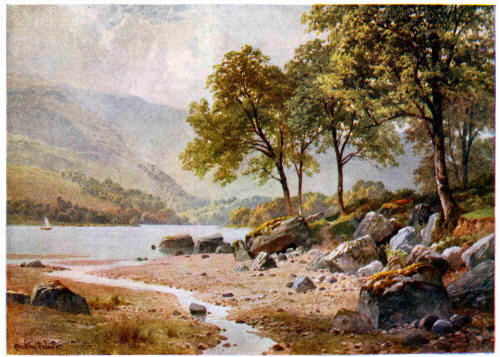

Birches by Loch Achray, Perthshire

Home, the author of Douglas, had an adventure

here, confined as prisoner of war in a Jacobite dungeon, from which he

escaped, with five fellow-captives, in quite romantic style ; and this, we

know, was one of the stages of Captain Edward Waverley's journey. Farther

up the river, another place of note is Cambusmore, where Scott spent the

youthful holidays that made him familiar with the Trossachs country.

Callander he does not mention, its name not fitting into his metre,

whereas its neighbour Dunblane's amenity to rhyme brought to be planted

there a flower of song at the hands of a writer who perhaps knew it only

by name. But Callander has grown into a snug little town of hotels and

lodging-houses below most lovely scenery, little spoiled by the chain of

lakes above being harnessed as water-works for thirsty Glasgow, whose

Bailie Nicol Jarvies now lord it over the country of Rob Roy and Roderick

Dhu.

Another way to the Trossachs is by "the varied realms

of fair Menteith," through which a railway joins the banks of the Forth

and the Clyde. The name of Menteith has an ugly association to Scottish

ears through Sir John Menteith, a son of its earl, who betrayed Wallace to

the English; the signal for these Philistines' onrush was given by his

turning a loaf upside down, and so to handle bread was long an insult to

any man of the execrated name. Sir John afterwards fought under Bruce; but

however Scottish nobles might change sides in the game of feudal

allegiance, the Commons were always true to patriotic resentment; and no

services of that house have quite wiped out the memory of a traitor

remembered as Gan among the peers of Charlemagne or Simon Girty on the

backwoods frontier of America. And fortune seems to have concurred in the

popular verdict, for till even the shadow of it died out in a wandering

beggar, little luck went with the title of Menteith, least of all in a

claim to legitimate heirship of the Crown; then this earldom seemed doubly

cursed when transferred to the Grahams, one of whom was ringleader in the

murder of James I.

Menteith, one of the chief provinces of old Scotland,

has shrunk to the name of a district described in a witty booklet by a son

of the soil, far travelled in other lands. [Notes on the District of

Menteith, by R. B. Cunninghame Graham.]

"A kind of sea of moss and heath, a bristly country (Trossachs is said to

mean the bristled land) shut in by hills on every side," in which " nearly

every hill and strath has had its battles between the Grahams and the

Macgregors"; but now "over the Fingalian path, where once the red-shank

trotted on his Highland garron, the bicyclist, the incarnation of the age,

looks to a sign-post and sees This hill is dangerous." Its stony fields

and lochans lying between hummocks are horizoned by grand mountains, among

which Ben Lomond, to the west, is the dominating feature, "in winter, a

vast white sugar-loaf; in summer, a prismatic cone of yellow and amethyst

and opal lights; in spring, a grey, gloomy, stony pile of rocks; in

autumn, a weather indicator; for when the mist curls down its sides, and

hangs in heavy wreaths from its double summit 'it has to rain,' as the

Spaniards say.

Menteith became a resort before Callander, when, early

in the eighteenth century, we find Clerk of Penicuik taking

Head of Loch Lomond, Looking up Glen Falloch, Perthshire

his family there on a "goat's whey campaign," for which

remedy the Highland borders were often visited in his day. At an earlier

day, canny Lowlanders would be shy of trusting themselves, on business or

pleasure, beyond the Forth; and, even later, we know how Bailie Nicol

Jarvie thought twice before venturing into the haunts of that "honest"

kinsman of his. As Ben Lomond dominates this landscape, so looms out the

memory of Rob Roy Macgregor, that doughty outlaw who, like Robin Hood, has

taken such hold on popular imagination. Graham as he is, one suspects the

above-quoted representative of the old earls to have his heart with an

ancestral enemy who practised a kind of wild socialism—

To spoil the spoiler as he may,

And from the robber rend the prey.

It appears that Scott had Rob Roy in his eye as a

model for Roderick Dhu, and it is the Macgregor country which he has

given to his fictitious Vich Alpines. Mr. Cunninghame Graham points out

how the Highland borders were always more troubled than the interior

clandom, and how here especially the vicinity of a rich lowland offered

constant temptation for followers of the "good old rule, the simple plan"

recorded by Wordsworth. The Forth made a boundary against these predatory

excursions, yet sometimes a Roderick Dhu would harry fields and farms as

far as the home of "poor Blanche of Devon," beyond Stirling. The "red

soldiers" in turn came to pass the Highland line. On Ellen's Isle women

and children took refuge from Cromwell's men; Monk marched by

Aberfoyle, noting for destruction its woods that harboured rebels; and not

to speak of Captain Thornton's unlucky expedition, no less authentic a

hero than Wolfe once commanded the fortress which the Georges placed at

Inversnaid, near Rob Roy's home, to bridle that broken clan of Ishmaelites.

The railway, from Glasgow or from Stirling, passes to

the south of the Loch of Menteith, with its islands, to which a short

divagation might be made. Here, on the " Isle of Rest," shaded by giant

chestnuts which tradition brings from Rome, are the ruins of a cloister

whither the child Queen Mary was carried for refuge after the battle of

Pinkie, before setting out for France with her playmate maids of honour.

Last night the Queen had four Marys,

To-night she'll have but three;

There was Mary Beaton and Mary Seaton

And Mary Carmichael and me.

Mary Livingston was the authentic fourth of the

quartette in those days, and Mary Fleming held the place of Mary

Carmichael. The luckless heroine of this touching ballad was a Mary

Hamilton supposed by Scott to have been one of the Queen's attendants

later on, but her identity is somewhat dubious ; and one writer shows

reason to believe that the story of her crime and punishment has been

strangely shifted from the Russian Court of Peter the Great, where she

might well exclaim—

Ah! little did my minnie think,

The night she cradled me

The lands that I should travel in,

The death that I should dee!

Beyond this lake a railway branch brings us to

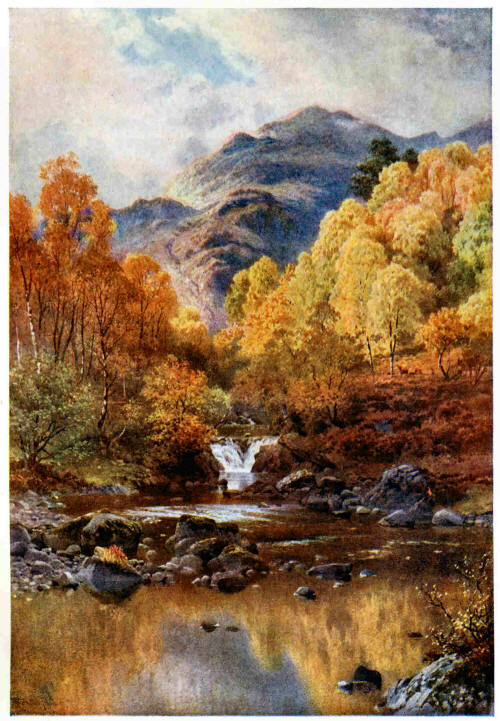

Golden Autumn, The Trossachs, Perthshire

Aberfoyle, on the banks of the "infant Forth," its

nursery name the Avon Dhu, "Blackwater," haunted like a child's dreams by

fairies of whom prudent Bailie Nicol Jarvie spoke under his breath, though

he professed to hold them as "deceits of Satan." Here the change-house of

Lucky M'Alpine has been replaced by an hotel offering all the comforts of

the Saltmarket, along with golf links and fishing at Loch Ard. As Ipswich

shows the very room in the White Hart occupied by Mr. Pickwick and the

green gate at which Sam Weller met Job Trotter, so among the lions here

are the ploughshare valiantly handled by Bailie Nicol Jarvie, nay, even

the identical bough from which he swung suspended by his coat tails. Such

relics let one guess why that worthy citizen would not give "the finest

sight in the Hielands for the first keek o' the Gorbals of Glasgow!" But

he might have taken another view had he seen the great slate quarries that

now scar the braes of Aberfoyle, or that pleasure-house on Loch Katrine

set apart for Glasgow magistrates to disport themselves at the source of

their city's water supply.

From Aberfoyle or from Callander, the rest of the

journey is by road to the Trossachs Hotel, which seems to represent

Fitz-James's imagination of "lordly tower" or "cloister grey"; then on

through the mile of bristling pass to the foot of Loch Katrine. How many a

peaceful stranger has passed this way since the Knight of Snowdoun's steed

here "stretched his stiff limbs to rise no more"! What "cost thy life, my

gallant grey" would be the fact that even in the poet's day, the path to

Ellen's Isle was more like a ladder than a road. Now the danger most to be

feared is from Sassenach cycling, which caused a coach accident in the

vicinity a few years ago. Umbrellas had replaced claymores so far back as

Wordsworth's time ; and waterproofs are the armour most displayed, where

once

Refluent through the pass of fear

The battle's tide was pour'd;

Vanish'd the Saxon's struggling spear,

Vanish'd the mountain-sword.

As Bracklinn's chasm, so black and steep,

Receives her roaring linn,

As the dark caverns of the deep

Suck the wild whirlpool in,

So did the deep and darksome pass

Devour the battle's mingled mass:

None linger now upon the plain,

Save those who ne'er shall fight again.

Macaulay, in his slap-dash style, has explained the

want of taste for the picturesque in a bailie or such like of more

romantic times. "He is not likely to be thrown into ecstasies by the

abruptness of a precipice from which he is in imminent danger of falling

two thousand feet perpendicular; by the boiling waves of a torrent which

suddenly whirls away his baggage and forces him to run for his life; by

the gloomy grandeur of a pass where he finds a corpse which marauders have

just stripped and mangled; or by the screams of those eagles whose next

meal may probably be on his own eyes." But Dr. Hume Brown {Early

Travellers in Scotland) shows how there were bold and not

unappreciative tourists in the Highlands before the era of return tickets.

Whatever the guidebooks say, it is certainly not the case that the

Trossachs were discovered by Scott. In Dr. T. Garnett's Tour through

the Highlands, published 1800, he relates a visit

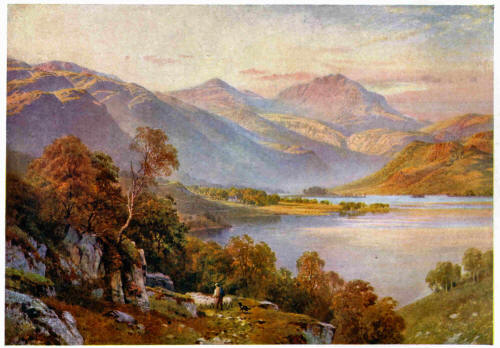

The River Teith, with Lochs Achray and Vennachar, Perthshire

to the "Drosacks," and speaks of the place as sought

out by foreigners. Several years before the publication of the Lady of

the Lake, Wordsworth, with Coleridge and his sister, on a Scottish

tour, turned aside to this beauty-spot, which they duly admired in spite

of the rain ; and there they met a drawing-master from Edinburgh on the

same picturesque-hunting errand. Dorothy Wordsworth's Journal tells

us how the cottars were amused to hear of their secluded home being known

in England; how two huts had been erected by Lady Perth for the

accommodation of visitors; and how a dozen years before the minister of

Callander had published an account of the Trossachs as a scene "that

beggars all description."

The bad weather proved too much for Coleridge, who

turned back from the tour here; and his muse seems not to have been

inspired by this land of the mountain which he found also a land of the

flood. Wordsworth, however, made several attempts to annex Scotland to his

native domain. Truth to tell, the lake poet's harp sounds sometimes out of

tune across the Border, as witness his woeful travesty of the "Helen of

Kirkconnel" story, and the philosophic considerations which he attributes

to Rob Roy over what may have been that bold outlaw's grave. There is one

verse in his "Highland Reaper" which seems a perfect epitome of the future

Laureate's qualities, who, if he "uttered nothing base," could come too

near being commonplace. "Will no one tell me what she sings?" is

surely in the flat tone which one irreverent critic describes as a

"bleat." "Perhaps the plaintive numbers flow"—is not this the false

gallop of eighteenth-century verse, out of which Wordsworth vainly

believed that he had broken his Pegasus? But in such pinchbeck setting,

what a pearl of price—

For old, unhappy, far-off things,

And battles long ago!

Thus to him, too, "Caledonia stern and wild" could

breathe her secret, while to put life into the raids and combats of long

ago was for another bard who plays drum and trumpet in the orchestra of

British poetry. I am not going to string vain epithets on the Trossachs,

familiar to all readers if only from the pages of their great advertiser.

But let me hint to tourists who come duly furnished with the Lady of

the Lake, that Black's Guide to the Trossachs includes an

excellent commentary on the poem from what may seem an unpoetical source,

the pen of an Astronomer-Royal, Sir G. B. Airey, whose topographical

analysis will be found most instructive. These scenes appear somewhat

trimmed since an old writer described the Highlands "as a part of the

creation left undrest." The lake edges have been smoothed off, as

the "unfathomable glades " of the Trossachs are opened up by a road, below

the line of the old pass and the hill tracks by which the Fiery Cross was

sped towards Strath-Ire.

For an account of this country as it is in our day, we

may refer to a French story by a writer named, of all names, Andre Laurie,

whose native heath ought to be the bonny braes of Maxwelton. This book has

the serious purpose of giving a view of English school athletics, and

pointing the moral that Frenchmen so trained would be all the fitter for

la revanche. The hero, sent to school in England, is, as part of

his educational course, taken by the schoolmaster on a shooting excursion

in the Highlands.

Veiled Sunshine, The Trossachs, Perthshire

They put up at the White Heart, one of the

principal hotels of Glascow, and the landlord is so interested in

their bold enterprise that he personally conducts them on the chasse

aux grouses. Nay more, he equips them with a pack of piebald pointers,

well trained to retrieve in water, which he had come by in a remarkable

manner: a certain Lord Stilton, breakfasting at the hotel, with true

British generosity made his host a present of these matchless hounds by

way of largesse for an excellent dish of trout—a rare treat, it

seems, in this part of the world.

The first day's proceedings of the sporting troop are

most notable. They "leave the civilised country" at Renfrew. How they get

across the Clyde does not appear ; but there are no doubt stepping-stones

in all Highland streams. Having thus invaded the Lennox, they forthwith

stalk its desolate moors from Loch Lomond to Loch Katrine, where as a

touch of local colour the author is careful to point out that one must not

use the word lakes. Nine or ten strong, the company is thrown out in

skirmishing order, those who have guns marching in front behind the dogs,

while the unarmed members are invited to bring up the rear "as simple

spectators." Scotland being such a proverbially hospitable country, they

do not judge it necessary to provide themselves with leave or license, but

their hotel-keeper for two or three shillings hires a bare-legged shepherd

in "a short petticoat" to show them where the game lies. In spite of this

liberality, towards the end of the day the bag amounts only to three or

four head, including one hare, explained to be a rara avis

hereabouts, and one fierce bull which has given a spice of danger to their

sport. In the evening, however, the grouse begin to "rise," spring up

"every instant under their feet," and nearly two dozen are brought down,

enough to serve for supper. The question of lodging presents more

difficulty, the Trossachs being an "absolutely desert" country without a

village for six leagues round; but the whole party are comfortably

accommodated in a fisherman's hut, fifteen to twenty feet square, which

must have been a tight fit for ten, even though there was no furniture

beyond a table, two benches and a sheepskin. With genuine Scottish pride

the fisherman refuses to accept a bawbee from his guests; though rather

too much given to "bird's eye tobacco" and "that abominable product of

civilisation Scotch whisky," he is a superior person, by his parents

designed for the national church, but the honour of "wearing a surplice,"

it is explained, had not seemed to him worth the frequent birching which

makes the discipline of parish schools in the north.

Next day, for a change, the strangers give themselves

up to the kindred sport of angling ; and two of them undertake the Alpine

ascent of one of the peaks above Loch Katrine, but, without a guide, come

to sore grief, and have to be rescued by a search party led by those

sagacious pointers in true Ben St. Bernard style. In such cases, our

author points out "the superiority of the savage over the civilised man,

at least in the desert." Only to the Highland fisherman had it occurred

that those luckless adventurers might want something to eat; but he,

taught by experience, produces in the nick of time a bottle of whisky, a

biscuit and a slice of bacon; and thus

Near Ardlui, Loch Lomond, Dumbartonshire

the perishing hero's life is saved to "dance a Scottish

gigue"—O M. Laurie, M. Laurie, O!

The dancing comes through a luxurious experience of

Highland high-life, when this band of youths fall in with an old

schoolfellow, a Scottish nobleman who bears what seems the exotic title of

Lord Camember, but his family name is that well-known aristocratic one of

Orton. He welcomes them to his castle, where his coming of age is being

celebrated by crowds strangely enormous for such a "desert country," who

are entertained under tents "vast as cathedrals," with splendid

hospitality open to all comers, fountains flowing with beer, speeches,

music, dancing, and fireworks. As bouquet of the festivities, he

invites the strangers to a review of his stags, driven together "in full

trot" till their gigantic antlers "gave the illusion of the marching

forest in the Macbeth legend." The drive past lasts more than an hour, in

the course of which are enumerated 5947 horns, so that, allowing for

absentees, the young lord estimates a round number of seven thousand as

the stock of his deer forest. There could have been no such head of game

in the district when Fitz-James galloped all the way from the Earn to Loch

Katrine after one stag, losing it as well as his way. One can't help

feeling that our author's excursion through the scenes of his story must

have been an equally rapid one.

The Trossachs pass leads us to that lake that gets a

fair-seeming name not from any saint, but from the Highland Caterans

who once infested its banks; and it is hinted that "Ellen's Isle" may

have come to be christened through Scott's mistaking the Gaelic word

Eilean (island). There was, indeed, a certain Helen Stuart who played

a grimly fierce part in defending this place of refuge, as related in the

poem, but her exploit was performed against Cromwell's soldiers. In sight

of the "Silver Strand," tourists are wont to take steamboat as far as

Stronachlachar, and there cross by coach to the "bonny, bonny banks of

Loch Lomond." They whose "free course" moves not by "such fixed cause,"

might well hold on to the head of Loch Katrine, crossing to Loch Lomond

over the wild heights of Glengyle; or they would not find it amiss to turn

back to Aberfoyle, thence past Loch Ard and the Falls of Ledard, following

the track round Ben Lomond on which Rob Roy led Osbaldistone and the

Bailie out of his country. But one knows not how to direct strangers to

that wild region vaguely outlined by the above-mentioned French author,

where our generation may shoot grouse and bulls as they go, and find

quarters in any convenient hut or castle, when the Trossachs hotel happens

to have "not a bed for love or money." His story, one fears, must be

counted with the mediaeval wonders of Loch Lomond, fish without fins,

waves without wind, and such a floating island as still emerges after hot

summers in Derwentwater.

Dorothy Wordsworth, for one, rather belittles Loch

Katrine as an "Ulswater dismantled of its grandeur and cropped of its

lesser beauties," though she compliments the upper part as "very pleasing,

resembling Thirlmere below Armboth." But no critic can carp at the fame of

Loch Lomond as the most beautiful lake in Scotland; and one author who, as

a native of the Lennox, is not indeed unprejudiced, Smollett to wit, gives

it the palm over all the lakes he has seen in Italy or Switzerland. Dr.

Chalmers wondered if there would not be a Loch Lomond in heaven.

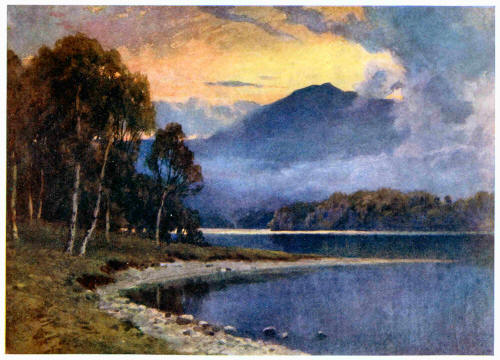

The Silver Strand, Loch Katrine, Perthshire

"A little Mediterranean" is the style given by a

seventeenth-century English tourist, Franck, to what Scott boldly

pronounces "one of the most surprising, beautiful, and sublime spectacles

in nature," its narrow upper fiord "lost among dusky and retreating

mountains," at the foot opening into an archipelago of wooded islands,

threaded by steamboats, while up the western shore runs one of the best

cycling roads in the kingdom, past memorials of Stuarts and Buchanans,

Colquhouns and wild Macfarlanes. On the other side are caves associated

with the adventures of Rob Roy, and spots sung by Wordsworth. And all this

wonderland is overshadowed by Ben Lomond, its ascent easily made on foot

or pony-back by a traveller not bound to do this whole round in one day.

But let him beware of getting lost in the mist and having to spend all

night on the mountain, as was the lot of that New England Sibyl, Margaret

Fuller. Also he should not imitate a facetious friend of mine who left his

card in the cairn at the top, and two or three days later received it

enclosed in this note: "Mr. Ben Lomond presents his compliments to

Mr.------and begs to say that not only does his position prevent him from

returning visits, but he has no desire for Mr.------'s further

acquaintance."

At the foot of Loch Lomond we regain the rails that

will carry us to Edinburgh, to Glasgow, to Stirling, or to the western

Highlands. The first stage is down the Vale of Leven to Dumbarton, arx

inexpugnabilis of old Scotland, its name Dunbritton recording

the older days when it was the stronghold of a Cumbrian kingdom. Here the

literary genius loci is that not very ethereal shade Tobias

Smollett, who, born on the banks of Leven, has nothing to say of the

Trossachs, but looked back on the scene of Roderick Random's pranks as an

eighteenth-century Arcadia, that could move him to a rare strain of

sentiment in his "Ode to Leven Water."

Devolving from thy parent lake,

A charming maze thy waters make,

By bowers of birch, and groves of pine,

And hedges flower'd with eglantine.

Still on thy banks, so gaily green,

May numerous herds and flocks be seen,

And lasses chanting o'er the pail,

And shepherds piping in the dale,

And ancient faith that knows no guile,

And industry embrown'd with toil,

And hearts resolved, and hands prepared,

The blessings they enjoy to guard.

Loch Achray and Ben Venue, Perthshire |