"Auld Reekie," as it is fondly called, still raises its

smokiest chimneys and most weathered walls along the "hoary ridge of

ancient town" that culminates in the Castle Rock, looking across a long

central line of gardens to the farther swell of land on which stands the

New Town of Scott's day. But New Town now seems a misnomer, since the

cramped site of the old city, itself much sweetened and aerated by

innovations, is surrounded by newer towns expanding in other directions.

Southwards, of late years, Edinburgh has grown more rapidly up to the foot

of the hills that here edge the suburbs of Newington, Grange, and

Morningside. Westwards she spreads out towards Corstorphine Hill and

Craiglockhart. On the east her progress is barred by the mass of Arthur's

Seat, but round the base of this creep rows of tall houses that will soon

connect her with Portobello, that minor Margate of the capital, now

comprised within her municipal boundaries. Northwards, she goes on

"flinging her white arms to the sea," which she almost touches at Granton

and Trinity; and a long unlovely street leads to the Piraeus of this

modern Athens, Leith, still stiffly standing aloof in civic independence.

Including Leith, which refuses to be included, the Scottish metropolis

began the century with a population not far short of 400,000.

On high in the midst of these modern settings, the

charms of Old Edinburgh are thrown into becoming relief, as the medley

smartness of Princes Street is enhanced by its facing the grim backs of

the High Street "lands." Ruskin and other critics have said hard things of

the New Town's architects; but their strictures do not go without

question. What, at all events, must strike strangers is an imposing

solidity of the modern buildings, whether tall "stairs"—Anglicé

flats—or roomy private houses, nearly all built of a grey stone that seems

in keeping with the atmosphere; and this not only in the central streets

and squares, but in outer suburbs, innocent of brick and stucco. If a too

classical regularity has been aimed at, this is tempered by the unevenness

of the ground, breaking up the " draughty parallelograms," giving vistas

into the open country, and at night such long panoramas of glittering

lights displayed on slopes and crests. The place, says R. L. Stevenson,

who has so well caught the picturesque points of his native city, "is full

of theatre tricks in the way of scenery. . . . You turn a corner, and

there is the sun going down into the Highland hills. You look down an

alley, and see ships tacking for the Baltic." And if the city fathers have

been ill advised in the past, its municipality may claim the credit of

being first in the kingdom to take powers for disinfecting it against the

plague of mendacious and hideous advertisements that are too much allowed

to pock our highways and byways.

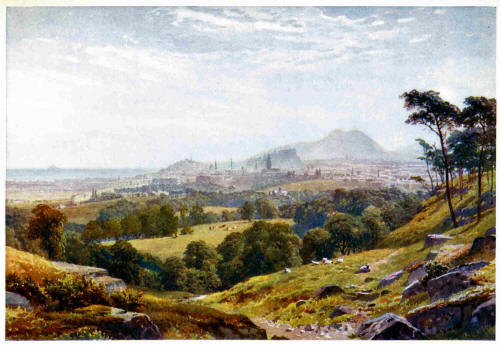

Edinburgh from "Rest and be Thankful"

A peculiar feature of the city is its "Bridges," by

which certain streets span others at different levels, physically and

socially. From the unique Dean Bridge, in the heart of the West End, one

overlooks what might be taken for a Highland glen but for the lines of

mansions that edge it above. When I came to Edinburgh as a homesick little

schoolboy, appalled by the "boundless continuity" of street, I devoted my

first Saturday freedom to an attempt at discovering the open country. This

was happily before the days of schoolboys being driven and drilled to

play. Striking the Water of Leith at Stockbridge, I turned along the path

leading into this glen that might well satisfy desires for a green

solitude. But on reaching the village of Dean, embedded below the bridge,

I climbed up to find myself beside the dome of St. George's Church, lost

deeper than ever in that bewildering city. Still, a little trimmed and

tamed, an oasis of wooded bank shuts in the rushing stream, now purified

and stocked with trout, where we were content to catch loaches and

sticklebacks.

What a loss to this city was the classically-minded

Gothicism or carelessness through which came to be rooted up so many noble

trees that once dotted the parks of Drumsheugh and Bellevue! But Edinburgh

has been well endowed afresh with open spaces and shrubberies, those that

separate the blocks of the New Town mainly private joint-stock paradises,

yet serving for public amenity. The Old Town is enclosed between the noble

stretch of the Princes Street Gardens on the north, and on the south the

open Meadows, with its "Philosopher's Walk" of Dugald Stewart's and

Playfair's days, rising into the Bruntsfield Links. Then the city is

almost ringed about by parks, more than one of them including grand

features of natural scenery. Philadelphia is the only city I know which

has such wild scenes at her very doors, in her case collected together in

the Fairmount Park, where miles of hill and river landscape have been left

almost untouched among the streets and suburbs, yet boasting no points so

noble as the head of Arthur's Seat, with its girdle of crags,

screes, and lakes.

This miniature Ben, imposing as it looks, is under 1000

feet high, and easily climbed. Those almost past their climbing days may

seek Blackford Hill on the south side, where Scott tells us that he

bird's-nested as a truant boy, and speaks of it as at a later day brought

under cultivation ; but it has relapsed again to its native wildness, laid

out as a rough park and as site for the squat domes of the new

Observatory. From this eminence one gets Marmion's view of the city, now

grown up to its foot, shut in between Arthur's Seat and the wooded ridge

of Corstorphine, and bounded to the north across the Firth by the heights

of Fife, above which, in clear weather, stand up the blue bastions of the

Highlands. Behind Blackford, one may keep up the wooded hollow of the

Hermitage, by a public path following the stream, and thus gain the Braid

Hills, overlooking the city a little farther back. Keeping along their

edge, at some risk from flying golf balls, one can hold on to the hotel

built between the old and the new south roads. Here, at the terminus of

suburban trams, looking to the Pentlands up the valley of the Braid Burn,

by which runs a field path towards Swanston, the country home of R. L.

Stevenson, one might hardly guess oneself so near a great city, but for

the lordly poorhouse and fever-hospital buildings to the back of

Craiglockhart Hill.

In the very heart of the city are view-points fine

enough to content hasty travellers, from the battlements of the Castle,

from the spire of Scott's Monument, from the slopes of the Calton

Hill, with its array of ready-made ruins and monuments with which

Edinburgh has sought to live up to her classical pretensions. This rises

beyond the east end of Princes Street, opposite the battlemented gaol, and

a little way past that Charing Cross of Auld Reekie, where its main ways

meet between the Post Office, the Register House and the tower of a new

North British Hotel looking down upon the glass roofs of the sunken

Waverley Station. At the other end of Princes Street, an opening before

the Caledonian Station may be called Edinburgh's Piccadilly Circus,

radiating into its Mayfair quarter. This end is dominated by the Castle,

suggesting to Algerian travellers a duodecimo edition of that wonderful

rock-set city Constantine. It shows little of the modern fortress, rather

a pile of ugly barracks which a Japanese cruiser could knock to pieces

from the Firth; but one understands how in old days its site made it a

Gibraltar citadel, that often could hold out when the town was overrun by

foemen taking care to keep themselves beyond range of the Castle guns.

Taylor, the Water Poet, who had seen something of war in his youth, judged

it "so strongly grounded, bounded, and founded, that by force of man it

can never be confounded." The King himself did not gain admittance on his

recent visit without a ceremony of summons by the Lord Lyon King of Arms;

but all and sundry, at reasonable hours, may stroll across its drawbridge

to lounge on the ramparts, to be conducted over historic relics by veteran

ciceroni, or to wait for the stunning report of the gun, which, fired from

Greenwich at one o'clock, brings every watch within hearing to the test.

From this "Maiden Castle," safe refuge for princesses

of the good old times, a conscientious tourist makes for Holyrood by the

long line of High Street and Canongate, bringing him past most of the

historic sites and monuments—the "Heart of Midlothian," the Parliament

House, the swept and garnished Cathedral of St. Giles, beside which John

Knox now lies literally buried in a highway, as was Dr. Johnson's pious

wish for him ; the restored Market Cross, the Tron Church, Knox's House,

which counts rather among Edinburgh's Apocrypha, and many another ancient

mansion, once alive with Scotland's proudest names, now degraded to an

Alsatia of huge dingy tenements, swarming forth vice and misery at

nightfall. The way narrows through an unsavoury slum as it approaches the

deserted home of kings, beyond which opens a park such as no king has at

his back door.

Holyrood was originally an abbey, founded by David I.

"in gratitude," says the legend, "for his miraculous deliverance from a

stag on Holy Rood Day, and prompted thereto by a dream." Similar stories

are told of many another prince less disposed to ecclesiastical

benefactions than David, that "sair saint to the crown"; even John of

England founded one abbey, at Beaulieu, as an act of grace prompted by

nightmare visions. Beside David's Abbey of the Holy Cross sprang up a

palace that, as well the sacred precincts, suffered much in the troubles

of the Stuart reigns, being frequently burned or spoiled by

Edinburgh Evening, from Salisbury Crags

English tourists of their period, on the last occasion

"personally conducted" by one Oliver Cromwell, who had small respect

either for palaces or abbeys. In Charles II.'s time it was rebuilt

somewhat after the style of Hampton Court, while the Abbey, devastated by

a Presbyterian mob, came to be refitted with a too heavy roof that crushed

it into utter ruin. The present building is thus modern, but for the ruins

behind, and the restored portion incorporating Queen Mary's apartments.

The name of the Sanctuary opposite was no vain one up till about half a

century ago, when impecunious debtors used to take asylum within its

bounds, privileged to issue free on Sundays, else venturing forth to feast

or sport only at the risk of thrilling adventures with bailiffs.

Everyone who has been to Edinburgh knows the sights of

this show place: the portraits of Scottish kings, more or less mythical,

"awful examples" as works of art, the whole gallery, it is said, done by a

Dutch painter of the seventeenth century for a lump sum of £250; the

tapestried rooms of Darnley; the Queen's bedchamber; and the dark stain on

the flooring where Rizzio is believed to have gasped out his life, after

being dragged from the side of his mistress. Every reader must know

Scott's story of the traveller in some patent fluid for removing stains,

who pressed the use of his nostrum on the horrified custodian. What every

stranger does not know is how this "virtuous palace where no monarch

dwells" is still used for functions of state. Annually, in May, the Lord

High Commissioner takes up his quarters here as representative of the

Crown in the General Assembly of the Church, when green peas ought to come

into season to make their first appearance on the

quasi-royal table. Ireland, that makes such loud boast of her grievances,

basks in the smiles of a Lord-Lieutenant all the year, while poor patient

Scotland has a blink of reflected royalty for one scrimp fortnight, during

which the old palace wakes to the life of levees, drawing-rooms,

and dinners, where black gowns and coats are more in evidence than in most

courtly circles. The Commissioner's procession from the palace to open the

Assembly lights up the old Canongate with a martial display; and more or

less festivity is held within the walls according to the wealth or

liberality of the Commissioner, who, like the Lord Mayor of London, should

be a rich man to fill his office with due eclat. But when King

Edward VII. recently visited Edinburgh, to the regret of the citizens, he

did not take up his quarters in the palace, pronounced unsuitable by the

prosaic reason of its drains being somewhat too Georgian, a matter that

has now been amended.

A more occasional function fitly transacted here is the

election of representative peers for Scotland in a new parliament. As

every schoolboy ought to know, our Constitution admits only sixteen

Scottish peers to sit in Parliament, most of them indeed having place

there in virtue of British peerages—the Duke of Atholl as Lord

Strange, for instance, the Duke of Montrose as Lord Graham, and so forth.

Of those left out in the cold, sixteen are "elected" by a somewhat

cut-and-dried process very free from the heat and excitement of

popular voting. As I have seen it, the ceremony seemed to lack

impressiveness. Some dozen gentlemen in pot hats and shooting jackets

assembled in the Picture Gallery before an audience chiefly consisting of

ladies, more than one of these legislators in mien and appearance

suggesting what Fielding says about Joseph Andrews, that he might have

been taken for a nobleman by one who had not seen many noblemen. Each of

the privileged order, in turn, wrote and read out a list of the peers for

whom he voted, usually ending "and myself." Certain practically-minded

peers sent in their votes by post. The most moving incident was the

expected one of an advocate in wig and gown rising to put in for a client

some unrecognised claim to a title or protest as to precedency, duly

listened to and noted down. The whole ceremony struck one as rather a

waste of time; but perhaps the same might be said of most ceremonies. One

thing has to be remembered about these unimposing lords, that they are a

highly select body in point of blue blood, all representing old families,

as the fount of their honour was dried up at the Union, and the king can

make an honest man as soon as a Scottish peer.

The tourist who comes in for any of such functions will

realise the truth of what R. L. Stevenson says for his native city:—

"There is a spark among the embers; from time to time

the old volcano smokes. Edinburgh has but partly abdicated, and still

wears, in parody, her metropolitan trappings. Half a capital and half a

country town, the whole city leads a double existence; it has long trances

of the one and flashes of the other; like the king of the Black Isles, it

is half alive and half a monumental marble. There are armed men and cannon

in the citadel overhead; you may see the troops marshalled on the high

parade; and at night after the early winter evenfall, and in the morning

before the laggard winter dawn, the wind carries abroad over Edinburgh the

sound of drums and bugles. Grave judges sit bewigged in what was once the

scene of imperial deliberations. Close by in the High Street perhaps the

trumpets may sound about the stroke of noon; and you see a troop of

citizens in tawdry masquerade; tabard above, heather-mixture trowser

below, and the men themselves trudging in the mud among unsympathetic

bystanders. The grooms of a well-appointed circus tread the streets with a

better presence. And yet these are the Heralds and Pursuivants of

Scotland, who are about to proclaim a new law of the United Kingdom before

two-score boys, and thieves, and hackney-coachmen."

Tourists are too much in the way of seeing no more of

Edinburgh than its historic lions and rich museums, as indicated in the

guide-books. I would invite them to pay more attention to the suburbs

straggling on three sides into such fine hill scenery as is the

environment of this city. Open cabs are easily to be had in the chief

thoroughfares; and Edinburgh cabmen have the name of being rarely decent

and civil, as if the Shorter Catechism made an antidote to the human

demoralisation spread from that honest friend of man, the horse. Give a

London Jehu something over his fare, and his first thought seems to be

that you are a person to be imposed upon; but I, for one, never had the

same experience here. I know of a stranger who took a cheaper mode of

finding his way through Edinburgh; he had himself booked as an express

parcel and put in charge of a telegraph messenger, who would not leave him

without a receipt duly signed at his destination. But the wandering

pedestrian is at great advantage where he seldom has out of sight such

landmarks as the Castle and Arthur's Seat. There is no better way of

seeing the city than from the top of the tramcars that run in all

directions, the main line being a circular

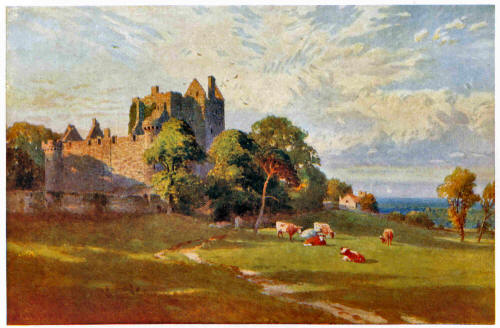

Craigmillar Castle, near Edinburgh

route from the Waverley Station round the west side of

the Castle, then through the south suburbs, and back beneath Arthur's Seat

to the Post Office. Public motor cars also ply their terror along the

chief thoroughfares. The trams are on the cable system, invented for the

steep ascents of San Francisco, but out of favour in most cities. The

excuse for its adoption here was that bunches of overhead wires would

spoil such amenities as are the city's stock in tourist trade. It has the

objectionable habit of keeping up along the line a rattle disquieting to

nervous people, while the car itself steals upon one like a thief in the

night; but it appears that accidents to life and limb are not so common as

hitches in the working.

The trams now run on Sunday, an innovation that shocks

many good folk, brought up in days when the streets of a Scottish city

were as stricken by the plague, unless at the hours when all the

population came streaming on foot to and from their different places of

worship. A few years ago, I felt it my duty to correct the late Max O'Rell,

who had gathered some wonderful stories supposed to illustrate the manners

of Scotland. As he related how, getting into an Edinburgh tramcar on

Sunday, his companion insisted on their riding inside not to be seen of

men, one was able to inform him that since the days of Moses no public

vehicle had disturbed Edinburgh's Sabbath quiet. It is not so now; and all

the old stories about "whustlin' on the Sabbath" and so forth will soon be

legends, so fast is the peculiar observance of Scottish piety melting

away.

R. L. Stevenson humorously called himself "a countryman

of the Sabbath," but this institution is not so clearly a native of

Scotland as has been taken for granted. John Knox played bowls on Sunday;

and the rigidity that came in later was due as much to English Puritanism

as to the thrawnness of Scottish revolt against Catholic practices.

Whatever its origin, Sabbatarianism once weighed heavily on human nature

north of the Tweed. "Is this a day to be talking of days!" was the

rebuke of the Highlander to a tourist who ventured to remark that it was a

fine Sunday. Not so many years ago, I have known a Highland farmer refuse

the loan of a girdle to bake scones for a breadless family, "not on the

Sabbath"; yet this orthodox worthy and his sons, living as far from a

church as from a baker's shop, seemed to spend most of the day of rest

lying by the roadside smoking their pipes and reading the newspaper. An

exiled Scot, in far distant lands, has told me how the shadow of the

coming Sabbath began to fall on his youth as early as Wednesday night. The

holy day was a term of imprisonment for juvenile spirits, its treadmill

two long services, chiefly sermon, sometimes run into one, or separated by

only a few minutes' interval, to economise short winter light in

which worshippers might have to trudge miles to church. It is in the

Highlands and other out-of-the-way parts, of course, that such austerities

linger, while the urban populations more readily adopt English compromises

on this head.

In Edinburgh one generation has seen a great thawing of

the Sabbath spirit. I can remember the excitement caused all over Scotland

by a sermon in which Dr. Norman Macleod proclaimed that there was no harm

in taking a walk on Sunday. The Scotsman, a paper that has never

much flattered its readers' prejudices, came out with a sly humorous

article headed "Murder of Moses' Law by Dr. Norman Macleod," and it is

said that some good people read this in the sense that the "broad" divine

had actually committed homicide. Even earlier, Edinburgh people had

tacitly sanctioned a walk to a cemetery, as echoing the teachings of the

pulpit. The story went that the present King, when at Edinburgh

University, was sternly denied admission to the Botanic Gardens on Sunday;

but he might unblamed have taken a stroll through the adjacent tombs of

Warriston. From the Dean Cemetery, the West End ventured on extending its

Sunday ramble as far as "Rest and be Thankful" on Corstorphine Hill; then

it was a fresh scandal when a very Lord of Session came to show himself on

this road in tweeds, instead of the full phylacteries that might attest

previous church-going. Of another judge living at Corstorphine it is told

that he once sought to mend the morals of a cobbler helplessly drunk at

his gate on Sunday afternoon, but was met by the hiccoughed repartee, "Wha's

you, without your Sabbath blacks?"

In my youth the police would put a stop to skating or

such like diversions on Sabbath; but now Sunday bicycles flit over the

country; the iniquity of a Sunday band is tolerated in the parks; while a

society is suffered to promote Sunday concerts and lectures indoors.

Another sign of the times is that Christmas in Edinburgh begins to be

almost as much observed as the national festival of New Year's Day,

whereas orthodox Presbyterianism once made a point of ignoring fasts and

feasts sanctioned by prelacy or popery. As for its own fasts, they have

long been transmuted into junketings; and the sacramental "preachings" of

large towns are now frankly abolished in favour of public holidays

answering to the English saturnalia of St. Lubbock, observed only by banks

across the Tweed. The Communion, in old days administered but once or

twice a year, and regarded in some parts with such awe that few ventured

to put themselves forward as participants, is now a frequent rite in

Presbyterian Churches, whose congregations are throwing off their horror

of ornament and ceremony, as may be seen in St. Giles. Old-fashioned

English rectors of the Simeon school have been known to shake their heads

at the services now read in the ears of descendants of that Jenny Geddes

who so forcibly testified against a prayer-book declared by ribald jesters

hateful to Scotland through its too frequent mention of "Collect."

The honest stranger, then, has nothing to fear from the

austerity of Scottish morals, not even the supposed risk of being married

by mistake. It will be his own fault if he fail to find a welcome across

the Tweed. Effusive manners are not the Scot's strong point, and he may be

accused of a certain suspicion of offence, kept sharp by the careless and

not ill-natured insolence of southrons who are so free with their jovial

jests about "bawbees" and such like, well-worn and rusty pleasantries

coined in the days of Bute's unpopularity and Johnson's bearish dogmatism.

Among the baser sorts of Scots are still current inverse sarcasms against

English "pock-puddings," conceived as fat and greedy; but they would have

to be fished up from a low social stratum by the travelling gent who

cannot understand that, however little disposed

Linlithgow Palace

Sandy may have been to hang his head for honest

poverty, he ill relishes its being flung in his face. "A sooth bourd is

nae bourd," says the old proverb; but now, what with tourists, and trade,

and Scotsmen who come back again, bringing the spoils of the world with

them, the reproach of poverty ceases to be so sore a one.

Though in the eyes of busy Glasgow Edinburgh may pass

as a retired capital, living on its means of attraction, it has; in fact

several industries from which to earn a livelihood. Along with the lodging

and amusing of strangers, it must do a good business in the tartans,

pebbles, silver-work, and other showy wares displayed in Princes Street

shop windows. "Edinbury Rock," done up in tartan wrappers, is much pressed

upon the notice of tourists; the same indeed, being sold in other towns

under their own name. As for shortbread, scones, biscuits, and other

manufactures of the "Land of Cakes," these have invaded London, where

every baker not a German is like to be a Scot. It will be noted by Cockney

revilers as a proof of Scotch thriftiness, which might bear another

interpretation, that what costs a penny in a London baker's shop is here

sold for a halfpenny. Well known to strangers are the Princes Street

confectioners' shops, several of them extensive restaurants like that one

which, crowning its storeys of accommodation, has a roof garden looking

upon the Castle opposite.

The staple trades of Edinburgh have come to be printing

and publishing, and, as the nettle grows near the dock, brewing and

distilling. The great Scottish publishing firms have of late years shown a

tendency to gravitate towards London; but more than one still keeps its

headquarters here, beside some of the largest and best printing

establishments in the kingdom. It must be confessed that what is spoken of

as "the trade," is whisky, too much consumed about the premises, as

visitors are apt to note. The worst shame a Scotsman need take for

Scotland is on account of what Englishmen specially distinguish as

"Scotch." I never heard sadder jest than the laughing comment of a group

of Dundee lasses, as they passed a braw lad wallowing in the gutter

at mid-day—"He's having his holidays!" Yet as to this reproach, something

might be said in plea for mitigation of judgment. Something to the purpose

was said by that experienced toper who explained how "whusky makes ye

drunk before ye are fu', but yill makes ye fu' before ye are drunk." The

whisky drunk by the lower classes here is a demon that takes no disguise.

It seems that, while there is more brutal intoxication in Scotland, there

may be less toping sottishness than in England. Men seen so helplessly

overcome at the ninth hour of a holiday are perhaps of ordinarily sober

habits, all the more readily affected by occasional indulgence in fiery

spirit. A woman frequenting public-houses implies a lower depth of

degradation. In the north, a larger proportion of the population

are abstainers; young people and the class of domestic servants for

instance, drink water where in English families they would expect beer. In

all classes, there are still too many Scotsmen religious in the worship of

their native Bacchus, vulgar and violent deity as he is; but every year

adds to the number of Protestants against this perverted fanaticism. By

the Forbes Mackenzie Act, all public-houses are

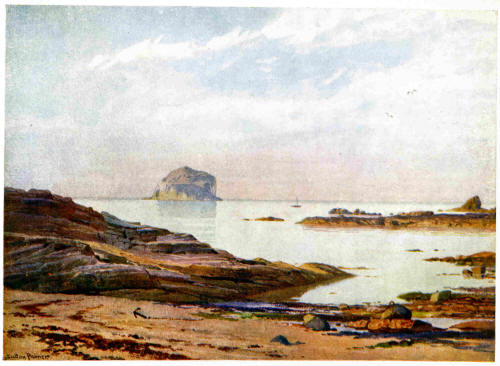

The Bass Rock - A Tranquil Evening

closed on Sunday, when, however, if all stories be

true, a good deal of shebeening or illicit drinking goes on in the

cities. It is not unreasonable to suppose that the austerity of Scottish

Sabbatarianism has driven many into vicious indulgence; and much is to be

hoped from the churches taking an interest in honest amusement as a help

and not a hindrance to religion. But a sneer often thrown out by strangers

against the supposed hypocrisy of Scotsmen, only shows ignorance of a

country where those most concerned about Sabbath observance have long been

the deadliest enemies of drinking habits.

Whisky, as well as golf, has now so masterfully invaded

England, that this can no longer be called "Scottish Drink," as it was not

by Burns. In his day, home-brewed beer was the Lowland beverage, of which

a Cromwellian soldier complained as more like brose for its thickness. Up

to our day "Edinburgh Ale" made the capital's chief contribution to the

heady gaiety of nations. Whisky came in from the Highlands, its name a

contraction of uisgebeatha, "water of life," which Burns and Scott

write usquebaugh, the Celtic word for water being the same that

appears in so many river names Esk, Usk, Exe, Axe, and so forth.

Even in the Highlands, this mountain dew would seem to have supplanted

beer within historic times; and old writers admire the temperance as much

as the honesty and courage of Highlanders. Both Highland and Lowland

gentlemen preferred brandy, in the days when, as Lord Cockburn tells us,

claret was hawked about the Edinburgh streets in a cart, a jug of any

reasonable size being filled for sixpence.

Firm and erect the Caledonian stood,

Old was his mutton, and his claret good.

Let him drink port! a beef-fed statesman cried.

He drank the poison and his spirit died.

The preference for French wine and spirits before the

days of Hanoverian fiscalities, relates to the old alliance with France,

which has left its mark also on Scottish speech. That warning cry "Gardy-loo"

(gardez I'eau), which gave such scandal to early English tourists,

was of course a survival of a far-spread practice in cities before the

days of drainage or even of ash-buckets (baquets). Many French

household words are used in Scotland at this day, as "caraff" (carafe),

"ashet" (assiette), a "jiggot" of mutton (gigot), a

"haggis" (hachis); and Burns's "silver tassie" was of course a

tasse. A "cummer" (commère) "canna be fashed" (sefacher)

to step out to the "merchant's," who may be "douce" or "dour" and an

"honest" man (honnete), though sharp in his bargains. "Ma certie

(certes), that's a braw (brave) vest!" quoth a lass to her lad,

a word here used like the French garcon or gars, while

gosse will be distinguished as a "laddie," who grows to be a "young

lad" in spite of orgies on sour "grozers" or "grozets" and "gheans," which

in France are groseilles and guignes, but in England

gooseberries and wild cherries. French names too have taken root in

Scotland, Janet (Jeannette) being very common with one sex, as Louis or

Ludovic is not unknown in the other. For the matter of that, one might

string together instances of how the well of Old English flows undefiled

by time in the north.

Then brought to him that maiden meek

Hose and shoon and sark and breek.

These words are used to this day in every Scottish

cottage, as once in the stately style of an early southron minstrel.

Shakespeare and the Bible show many picked phrases which are now wild

flowers in the north; and high example might be found for the shalls

and wills that here run loose from the enclosures of modern

grammarians. But as Mr. David MacRitchie suggests in an interesting

pamphlet "to doubt that one is colded and can't go to the

church" seem rather specimens of French idioms transplanted during the

three centuries or so that Capets and Stuarts stood together against the

Plantagenets.

Protestantism availed to draw Scotland from the arms of

France into those of England; then Prelacy and Presbytery set the near

neighbours again at odds. For some generations, the young Scotsmen who had

once sought the Catholic schools of the Continent, were more in the way of

finishing their education at Dutch or German Universities. Scotland had

also an old connection, chiefly in the way of trade, with Scandinavia and

Poland, in both of which countries Scottish family names are naturalised,

as Swedish Dicksons and Polish Gordons. Scots students of our day still

look to Germany, under whose professors they are apt to forget the Shorter

Catechism for the categories of Kant and the secret of Hegel. The Union

was not fully consummated till Macs began to make themselves at home in

Oxford and Cambridge, while for a time the renown of Scottish philosophy

drew some of the promising English youth to Edinburgh, whose medical

school kept up the attrac