|

The Clan Rose,

descended from Hugh Rose of Geddes, came over from Ireland in the early 12th century. They were,

before the forfeiture of the last Lord of the Isles, vassals of the old Earls of Ross.

They are quite separate in origin from Clan Ross. Mr Hugh Rose, the geologist of the

Kilravock Family, believed them to be English in origin because of their coat of arms

which contains three bouggets (buckets) which was similar to the English family of Roos

but this similarity was also carried by other families. The family of Rose of Kilravock

(pronounced Ross of Kilraik) appear to have settled in Nairn, in the North of Scotland, in

the reign of David the First, around the year 1219 when Hugh Rose of Geddes was witness to

the foundation of the Priory of Beauly. The name Rose of Geddes changed to Rose of

Kilravock when Hugh Rose of Geddes' son, of the same name, acquired the lands of Kilravock

through marriage, Kilravock becoming the chief title of the family. The Roses enjoyed the

friendship of the MacKintoshes from a very early date, and by an act of council dated 28th

July 1643, 'The broken men of the name of Rose were bound upon MacKintosh who each ordained

to be accountable for them'. The French Connection with the Rose of Kilravock family is

with J.A. Rose who was an extraordinary player in the French Revolution. He was born in

Scotland in 1757 and went to Paris in his early years. He became an Usher of the National

Assembly but raised himself above that position to become closely related to distinguished

figures of that eventful epoch. He was able to inform the unfortunate Louis the Sixteenth

of his imminent demise and did likewise for Marie Antoinette. Therefore he was thought of

as playing a better role than that of the fictional Scarlet Pimpernel. Other septs

associated with Clan Rose are Barron, Geddes, Baron, Ross.

Another Account of the Clan

BADGE: Ros-mhairi fiadhaich (Andromeda

media) wild rosemary.

As

with many other clans of the north, the origin of the Roses of Kilravock

has been the subject of considerable debate. It has been urged that the

name is derived from the Gaelic" Ros," a promontory, in the same

way as that of the Rosses farther north; but in Douglasís Baronage the

similarity of the coat armour of the chiefs to that of the Rooses or Roses

of Normandy and England is taken as evidence that the race was of Saxon

origin, and in his account of the house in Sketches of Early Scottish

History, Mr. Cosmo Innes, who was closely connected with the family,

and had made an exhaustive study of its charters and other documents,

supports the Norman source. Innes declares the history of the house

written in 1683-4 by Mr. Hew Rose, parson of Nairn, to be a careful and

generally very correct statement of the pedigree of the family. As

with many other clans of the north, the origin of the Roses of Kilravock

has been the subject of considerable debate. It has been urged that the

name is derived from the Gaelic" Ros," a promontory, in the same

way as that of the Rosses farther north; but in Douglasís Baronage the

similarity of the coat armour of the chiefs to that of the Rooses or Roses

of Normandy and England is taken as evidence that the race was of Saxon

origin, and in his account of the house in Sketches of Early Scottish

History, Mr. Cosmo Innes, who was closely connected with the family,

and had made an exhaustive study of its charters and other documents,

supports the Norman source. Innes declares the history of the house

written in 1683-4 by Mr. Hew Rose, parson of Nairn, to be a careful and

generally very correct statement of the pedigree of the family.

The original patrimony of

the Roses appears to have been the lands of Geddes in the county of

Inverness. In the days of Alexander II., as early as 1219, Hugh Rose of

Geddes appears as a witness to the founding of the Priory of Beaulieu, now

Beauly. The founders of that priory were the Byssets, at that time one of

the great houses of the north, the downfall of whose family forms one of

the strangest stories of Alexanderís reign. The incident is detailed in

Wyntounís Chronicle. In 1242, after a great tournament at

Haddington, Patrick, the young Earl of Atholl, was treacherously murdered

and "burnt to coals" in his lodging at the west end of that

town. Suspicion fell upon the Byssets, who were at bitter feud with the

house of Atholl. Sir William Bysset had just entertained the King and

Queen at his castle of Aboyne, and on the night of the murder had sat late

at supper with the Queen in Forfar. In vain the Queen offered to swear his

innocence. In vain Bysset himself had the murderers cursed "Wyth buk

and bell," and offered to prove his innocence by the ordeal of

battle. All men believed him guilty. The Byssets saw their lands harried

utterly of goods and cattle, and before the fury of the powerful kinsmen

of Atholl, they were finally banished the Kingdom. Sir John de Bysset,

however, had left three daughters, the eldest of whom inherited the lands

of Lovat and Beaufort, and became ancestress of the Frasers, while the

youngest inherited Redcastle in the Black Isle and Kilravock on the River

Nairn, and married Sir Andrew de Bosco. Mary, one of the daughters of this

latter union, married Hugh Rose of Geddes, and brought him the lands of

Kilravock and of Culcowie in the Black Isle as her marriage portion. This

was at the latter end of the reign of Alexander III., and from that day to

this the Roses have been lairds of Kilravock in unbroken succession.

No house in Scotland seems

to have kept more carefully its charters and family papers from the

earliest times, and from these Cosmo Innes derived many interesting facts

for his sketch of the intimate customs and history of this old Scottish

family.

From a very early time,

even before there is evidence of their lands having been erected into a

feudal barony, the Roses were known as Barons of Kilravock. They were

never a leading family in the country. The heads of the house preferred to

lead a quiet life, and though by marriage and otherwise they acquired and

held for many generations considerable territories in Ross-shire and in

the valleys of the Nairn and the Findhorn, we find them emerging only

occasionally into the limelight of history. For the most part the Roses

intermarried with substantial families of their own rank. William, son of

the first Rose of Kilravock, married Morella or Muriel, daughter of

Alexander de Doun, and Andrew, his second son, became ancestor of the

Roses of Auchlossan in Mar. Williamís grandson, Hugh, again, married

Janet, daughter of Sir Robert Chisholm, Constable of Urquhart Castle, who

brought her husband large possessions in Strathnairn. This chiefís

grandson, John, also, who succeeded in 1431, married Isabella, daughter of

Cheyne, laird of Esslemont in Aberdeenshire, and further secured his

position by procuring from the King a feudal charter de novo of all

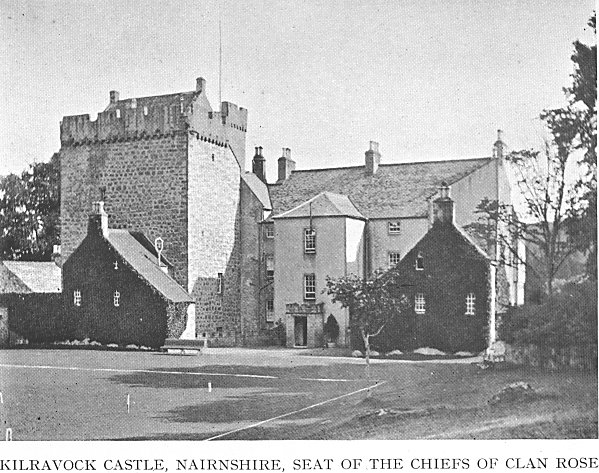

his lands. It was Johnís son Hugh who built the existing old tower of

Kilravock in 1460, and his energy, or his need for protection, is shown by

the fact, recorded as marvellous, that he finished it within a year.

The family at this time was

at serious variance with one of its most powerful neighbours, the Thane of

Cawdor. This Thaneís father, six years earlier, had built the present

keep of Cawdor Castle, and Thane William himself had made one of the best

matches of his time by marrying a daughter of Alexander Sutherland of

Dunbeath, whose wife was a daughter of one of the Lords of the Isles.

Thane William was an ambitious man. He had his estates changed into a

Crown holding by resigning them into the hands of the King and procuring a

new charter, and, to make sure of the permanence of his family, he set

aside with a pension his eldest son, William, who had some personal

defect, and settled the whole thanedom and heritage of the family on his

second son, John, whom, to close the feud between the families, he married

to Isabella, daughter of Rose of Kilravock. The marriage, however, was not

happy, and out of it arose one of the most curious romances of the north.

The young Thane John did

not long survive his marriage; he died in 1498, leaving as sole heiress to

the Cawdor estates an infant daughter, Muriel. The old Thane, William, and

his four sons were naturally furious. They did their best to have Muriel

declared illegitimate; but their efforts were useless. By reason of the

new charter the child was a ward of the Crown, and the Earl of Argyll, who

was then Justiciar of Scotland, procured her wardship and marriage from

James IV. The Roses were no doubt glad to have the keeping of the child

entrusted to so powerful a guardian, but old Lady Kilravock was evidently

not without her doubts as to the good faith of Murielís new protector.

When the Earlís emissary, Campbell of Inverliver, arrived at Kilravock

to convey the child south to Loch Awe, the old lady is said to have thrust

the key of her coffer into the fire, and branded Muriel with it on the

thigh.

Inverliver bad not gone far

on his way to the south when he was overtaken by the childís four uncles

and their following. With shrewd ability he devised a stratagem. Sending

Muriel off hotfoot through the hills under a small guard, he dressed a

stook of corn in her clothes, placed it where it could be seen by the

enemy, and proceeded to give battle with the greater part of his force.

Seven of his sons, it is said, fell before he gave way, and even then he

only retired when he felt sure the child was far beyond the reach of

pursuit. When someone afterwards asked whether he thought the prize worth

such sacrifice, and suggested that the heiress might die before reaching

womanhood, he is said to have replied, "Muriel of Cawdor will never

die as long as thereís a red-haired lassie on the shores of Loch

Awe." Muriel, however, survived, and indeed lived to a good old age.

The Earl of Argyll married her when twelve years old to his second son,

Sir John Campbell, and the Earls of Cawdor of the present day are directly

descended from the pair.

Hugh Rose of Kilravock,

grandson of him who built the tower, for some reason now unknown seized

William Galbraith, Abbot of Kinloss, and imprisoned him at Kilravock. For

this he was himself arrested and kept long a prisoner in Dunbarton Castle,

then commanded by Sir George Stirling of Glorat. A deed is extant by

which, while a prisoner, in June, 1536, the laird engaged a burgess of

Paisley as a gardener for Kilravockó"Thom Daueson and ane servand

man with him is comyn man and servand for all his life to the said Huchion."

The next laird was known as

the Black Baron. He lived in the troublous time of the Reformation, and in

his youth he fought and was made prisoner at Pinkiecleugh; yet he managed

to pay his ransom, 100 angels, and to provide portions for his seventeen

sisters and daughters, built the manor place beside his ancient tower, and

reigned as laird of Kilravock for more than fifty years. It was in his

time that Queen Mary paid her visit to Kilravock. The Castle of Inverness,

of which the Earl of Huntly was keeper, had closed its gates against her

and her half-brother, whom she had just made Earl of Moray, and the Queen,

while preparing to storm the stronghold, took up her quarters at Kilravock.

Here possibly it was that she made the famous remark that she

"repented she was not a man, to know what life it was to lie all

night in the fields, or walk the rounds with a Jack and knapscull." A

few days later, overawed by her preparations, the captain of Inverness

Castle surrendered and was hanged, and shortly afterwards the Queen

defeated Huntly himself at Corrichie, and brought the great rebellion in

the north to an end.

The Black Baron of

Kilravock was justice depute of the north under Argyll, sheriff of

Inverness and constable of its castle under Queen Mary, and commissioner

for the Regent Moray. He lived to be summoned to Parliament by James VI.

in 1593.

In the time of the eleventh

and twelfth Barons we have pictures of Kilravock as a happy family house,

where sons and grandsons were educated and brought up in kindly, wise, and

hospitable fashion. The thirteenth baron, who died young in 1649, was well

skilled in music, vocal and instrumental. Hugh, the fourteenth baron,

lived through the trying times of Charles II. and James VII., but, though

sharing his wifeís warm sympathy with the persecuted Covenanters,

managed himself to avoid the persecutions of his time. The fifteenth

baron, again, educated in a licentious age, began life as a supporter of

the divine right of kings, but afterwards admitted the justice and

necessity of the Revolution. He voted against the Act of Union, but

declared openly for the Protestant Succession, and, after the Union, was

appointed one of the Scottish Commissioners to the first Parliament of

Great Britain. On the outbreak of the Earl of Marís rebellion in 1715 he

stood firm for King Georgeís Government, armed two hundred of his clan,

kept the peace in his country side, and maintained Kilravock Castle as a

refuge for persons in dread of harm by the Jacobites. He even planned to

reduce the Jacobite garrison at Inverness, and, along with Forbes of

Culloden and Lord Lovat, blockaded the town. His brother, Arthur Rose, who

had but lately been ransomed from slavery with the pirates of Algiers, and

whose portrait in Turkish dress may still be seen at Kilravock, tried to

seize the garrison. At the head of a small party he made his way to the

Tolbooth, but was betrayed by his guide. As Rose pushed past the door,

sword in hand, the fellow called out "An ehemy! an enemy I" Upon

this the guard rushed forward, shot him through the body, and crushed the

life out of him between the door and the wall. On hearing of his brotherís

end, Kilravock sent a message to the garrison, ordering it to leave the

place, or he would lay the town in ashes, and so assured were the governor

and magistrates that he would keep his word that they evacuated the town

and castle during the night, and he entered and took possession next day.

In 1704 Kilravockís

following was stated as five hundred men, but in 1725 General Wade

estimated it at no more than three hundred.

In 1734 the sixteenth baron

was returned to Parliament for Ross-shire, and he might have been elected

again, but preferred the pleasures of country life. He built the house of

Coulmonie on the Findhorn, and married Elizabeth Clephane, daughter of a

soldier of fortune, and friend of the Countess of Sutherland. He was

engaged in the quiet life of a country gentleman, hawking and shooting and

fishing, when in 1745 the storm of Jacobite rebellion again swept over the

country. Two days before the battle of Culloden, Prince Charles Edward

rode out from Inverness to bring in his outposts on the Spey, which were

retiring before Cumberlandís army, and he spent an hour or two at

Kilravock Castle. He kissed the children, begged a tune on the violin from

the laird, and walked out with him to see some plantations of trees he was

making. Before leaving he expressed envy of the lairdís peaceful life in

the midst of a country so disturbed by war. Next day the Duke of

Cumberland arrived at the Castle, where it is said he spent the night. His

boots, a pair of huge Wellingtons, are still to be seen there. In course

of talk he remarked to the laird, "You have had my cousin here?"

and on Kilravock hastening to explain that he had had no means of refusing

entertainment, the Duke stopped him with the remark that he had done quite

right. The laird was then Provost of Nairn, and a silver-mounted drinking

cup of cocoanut still preserved at Kilravock bears the inscription,

"This cup belongs to the Provost of Nairn, 1746, the year of our

deliverance. A bumper to the Duke of Cumberland."

For a hundred years the

Sheriffship of Ross had been all but hereditary in the family, and after

the abolition of heritable jurisdictions in 1746, Hugh Rose, the

seventeenth baron, was still appointed sheriff depute by the King. Books

and music, gardening and hospitality, filled up the pleasant life at

Kilravock in this lairdís time. He himself was a good classical scholar,

and was consulted constantly by Professor Moore, of Glasgow, regarding his

great edition of Homer.

It was the daughter and

heiress of this laird who was known in so much of the correspondence of

the north in her time as Mrs. Elizabeth Rose. This lady succeeded her

brother, the eighteenth baron, in 1782, married her cousin, Hugh Rose of

Brea, the heir-male, and lived through a long widowhood till 1815. Lady

Kilravock, as she was called, had a high reputation for taste in music and

literature, and when Robert Burns set out on his Highland tour in the

autumn of 1787, he carried an introduction to her from her cousin, Henry

MacKenzie, the "Man of Feeling." The Poetís two visits to the

castle within a couple of days of each other are noted in his journal, and

referred to in a letter in the following spring.

Below the crag on which the

castle stands, winds the wild sequestered path known as the Fairy Walk, on

which Burns is said to have rambled with the ladies of the house. The

highly accomplished character of Mrs. Elizabeth Rose is also attested in

the writings of Hugh Miller and other well-known authors.

From first to last, indeed,

the Roses of Kilravock stand distinguished among the chiefs of Highland

clans for their refined and literary taste. Something of the popular

impression of this is to be seen in the well-known ballad of "Sir

James the Rose," which had probably some member of the house for its

subject. Major James Rose, the late laird and head of the house, was

Lord-Lieutenant of Nairnshire from 1889 to 1904. His son, the present

laird, Colonel Hugh Rose, had just retired from active service in the Army

when the Great European War broke out in 1914. He then again offered his

services, and shortly after the beginning of hostilities was appointed

Camp Commandant of one of the divisions of the British Expeditionary Force

in France. Among other distinguished holders of the name in recent times

have been William Stewart Rose, the well-known scholar, poet, and friend

of Sir Walter Scott, and his nephew, Hugh Henry Rose, Lord Strathnairn,

who won his way by distinguished services in India to the position of

Commander-in-Chief in that great dependency.

|