|

The clan Anaba or Macnab has been said by some

to have been a branch of the Macdonalds, but we have given above a bond of manrent which

shows that they were allied to the Mackinnons and the Macgregors. "From their

comparitively central position in the Highlands", says Smibert, "as well as

other circumstances, it seems much more likely that they were of the primitive Albionic

race, a shoot of the Siol Alpine". The chief has his residence at Kinnell, on the

banks of the Docjart, and the family possessions, which originally were considerable, lay

mainly on the western shores of Loch Tay. The founder of the Macnabs, like the founder of

the Macphersons, is said to have belonged to the clerical profession, the name Mac-anab

being said to mean in Gaelic, the son of the abbot. He is said to have been abbot of

Glendochart.

The Macnabs were a considerable clan before the reign of Alexander III. When Robert the

Bruce commenced his struggle for the crown, the baron of Macnab, with his clan, joined the

Macdougalls of Lorn, and fought against Bruce at the battle of Dalree. Afterwards, when

the cause of Bruce prevailed, the lands of the Macnabs were ravaged by his victorious

troops, their homes burnt, and all their family writs destroyed. Of all their possessions

only the barony of Bowain or Bovain, in Glendochart, remained to them, and of it, Gilbert

Macnab of that ilk, from whom the line is usually deduced, as the first undoubted laird of

Macnab, received from David II, on being reconciled to that monarch, a charter, under the

great seal, to him and his heirs whomsoever, dated in 1336. He died in the reign of Robert

II.

His son, Finlay Macnab, styled of Bovain, as well as "of that ilk", died in the

reign of James I. He is said tohave been a famous bard. According to tradition he composed

one of the Gaelic poems which Macpherson attributed to Oaaian. He was the father of

Patrick Macnab of Bovain and of that ilk, whose son was named Finlay Macnab, after his

grandfather. Indeed, Finlay appears to have been, at this time, a favourite name of the

chief, as the next three lairds were so designated. Upon his father's resignation, he got

a charter, under the great seal, in the reign of James III, of the lands of Ardchyle, and

Wester Duinish, in the barony of Glendochart and county of Perth, dated January 1, 1486.

He had also a charter from James IV, of the lands of Ewir and Leiragan, in the same

barony, dated January 9, 1502. He died soon thereafter, leaving a son, Finlay

Macnab,

fifth laird of Macnab, who is witness in a charter, under the great seal, to Duncan

Campbell of Glenorchy, wherein he is designed "Finlaus Macnab, dominus de

eodem", &c, Sept 18, 1511. He died about the close of the reign of James V.

His son, Finlay Macnab of Bovain and of that ilk, sixth chief from Gilbert, alienated or

mortgaged a great portion of his lands to Campbell of Glenorchy, ancestor of the Marquis

of Breadalbane, as appears by a charter to "Colin Campbell of Glenorchy, his heirs

and assignees whatever, according to the deed granted to him by Finlay

Macnab of Bovain,

24th November 1552, of all and sundry the lands of Bovain and Ardchyle, &c, confirmed

by a charter under the great seal from Mary, dated 27th June 1553". Glenorchy's right

of superiority the Macnabs always refused to acknowledge.

His son, Finlay Macnab, the seventh laird, who lived in the reign of James VI, was the

chief who entered into the bond of friendship and manrent with his cousin, Lauchlan

Mackinnon of Strathairdle, 12th July 1606. This chief carried on a deadly feud with the

Neishes or M'Ilduys, a tribe which possessed the upper parts of Strathearn, and inhabited

an island in the lower part of Loch Earn, called from them Neish Island. Many battles were

fought between them, with various success. The last was at Glenboultachan, about two miles

north of Loch Earn foot, in which the Macnabs were victorious, and the Neishes cut off

almost to a man. A small remnant of them, however, still lived in the island referred to,

the head of which was an old man, who subsisted by plundering the people in the

neighbourhood. One Christmas, the chief of the Macnabs had sent his servant to Crieff for

provisions, but, on his return, he was waylaid, and robbed of all his purchases. He went

home, therefore, emply-handed, and told his tale to the laird. Macnab had twelve sons, all

men of great strength, but one in particular exceedingly athletic, who was called for a

bye name, Iain mion Mac an Appa, of "Smooth John Macnab". In the evening, these

men were gloomily meditating some signal revenge on their old enemies, when their father

entered, and said in Gaelic, "The night is the night, if the lads were but

lads!". Each man instantly started to his feet, and belted on his dirk, his claymore,

and his pistols. Led by their brother John, they set out, taking a fishing boat on their

shoulders from Loch Tay, carrying it over the mountains and glens till they reached Loch

Earn, where they launched it, and passed over to the island. All was silent inthe

habitation of Neish. Having all the boats at the island secured, they had gone to sleep

withour fear of surprise. Smooth John, with his foot dashed open the door of Neish's

house; and the party, rushing in, attacked the unfortunate family, every one of whom was

put to the sword, with the exception of one man and a boy, who concealed themselves under

a bed. Carrying off the heads of the Neishes, and any plunder they could secure, the

youths presented themselves to their father, while the piper struck up the pibroch of

victory.

The next laird, "Smooth John", the son of this Finlay, made a distinguished

figure in the reign of Charles I, and suffered many hardships on account of his attachment

to the royal cause. He was killed at the battle of Worcester in 1651. During the

commonwealth, his castle of Eilan Rowan was burned, his estates ravaged and sequestered,

and the family papers again lost. Taking advantage of the troubles of the times, his

powerful neighbour, Campbell of Glenorchy, in the heart of whose possessions

Macnab's

lands were situated, on the pretence that he had sustained considerable losses from the

clan Macnab, got possession of the estates in recompense thereof.

The chief of the Macnabs married a daughter of Campbell of Glenlyon, and with one daughter

had a son, Alexander Macnab, ninth laird, who was only four years old when his father was

killed on Worcester battle-field. His mother and friends applied to General Monk for some

relief from the family estates for herself and children. That general made a favourable

report on the application, but it had no effect.

After the Restoration, application was made to the Scottish estates, by Lady

Macnab and

her son, for redress, and in 1661 they received a considerable portion of their lands,

which the family enjoyed till the beginning of the present century, when they were sold.

By his wife, Elizabeth, a sister of Sir Alexander Menzies of Weem, Baronet, Alexander

Macnab of that ilk had a son and heir, Robert Macnab, tenth laird, who married Anne

Campbell, sister of the Earl of Breadalbane. Of several children only two survived, John,

who succeeded his father, and Archibald. The elder son, John, held a commission in the

Black Watch, and was taken prisoner at the battle of Prestonpans, and, with several

others, confined to Doune Castle, under the charge of Macgregor of Glengyle, where he

remained till after the battle of Culloden. The majority of the clan took the side of the

hosue of Stuart, and were led by Allister Macnab of Inshewan and Archibald

Macnab of

Acharne.

John Macnab, the eleventh laird, married the only sister of Francis Buchanan, Esq of

Arnprior, and had a son, Francis, twelfth laird.

Francis, twellfth laird, died, unmarried, at Callander, Perthshire, May 25, 1816, in his

82d year. One of the most eccentric men of his time, many anecdotes are related of his

curious sayings and doings.

We give the following as a specimen, for which we are indebted to Mr Smibert's excellent

work on the clans:-

"Macnab had an intense antiphathy to excisemen, whom he looked on as a race of

intruders, commissioned to suck the blood of his country: he never gave them any better

name than vermin. One day, early in the last war, he was marching to Stirling at the head

of a corps of fencibles, of which he was commander. In those days the Highlanders were

notorious for incurable smuggling propensities; and an excursion to the Lowlands, whatever

might be its cause or import, was an opportunity by no means to be neglected. The

Breadalbane men had accordingly contrived to stow a considerable quantity of the genuine

'peat reek' (whisky) into the baggage carts. All went well with the party for some time.

On passing Alloa, however, the excisemen there having got a hint as to what the carts

contained, hurried out by a shorter path to intercept them. In the meantime,

Macnab,

accompanied by a gillie, in the true feudal style, was proceeding slowly at the head of

his men, not far in the rear of the baggage. Soon after leaving Alloa, one of the party in

charge of the carts came running back and informed their chief that they had all been

seized by a posse of excisemen. This intelligence at once roused the blood of

Macnab. 'Did

the lousy villans dare to obstruct the march of the Breadalbane Highlanders!' he

exclaimed, inspired with the wrath of a thousand heros; and away he rushed to the scene of

contention. There, sure enough, he found a party of excisemen in possession of the carts.

'Who the devil are you?' demanded the angry chieften. 'Gentlemen of the excise', was the

answer. 'Robbers" thieves! you mean; how dare you lay hands on His Majesty's stores?

If you be gaugers, show me your commission'. Unfortunately for the excisemen, they had not

deemed it necessary in their haste to bring such documents with them. In vain they

asserted their authority, and declared they were well known in the neighbourhood.'Ay, just

what I took ye for; a parcel of highway robbers and scoundrels. Come, my good fellows',

(addressing the soldiers in charge of the baggage, and extending his voice with the lungs

of a stentor), 'prime! - load! -' The excisemen did not wait the completion of the

sentance; away they feld at top speed towards Alloa, no doubt glad they had not caused the

waste of His Majesty's ammunition. 'Now, my lads', said Macnab, 'proceed - your shisky's

safe'".

He was a man of gigantic height and strong originality of character, and cherished many of

the manners and ideas of a Highland gentleman, having in particular a high notion of the

dignity of the chieftainship. He left numerous illegitimate children.

The only portion of the property of the Macnabs remaining is the small islet of InnisBuie,

formed by the parting of the water of the Dochart just before it issues into Loch Tay, in

which is the most ancient burial place of the family; and outside there are numerous

gravestones of other members of the clan. The lands of the town of Callander chiefly

belong to a descendant of this laird, not in marriage.

Archibald Macnab of Macnab, newphew of Francis, succeeded as thirteenth chief. The estates

being considerably encumbered, he was obliged to sell his property for behoof of his

creditors.

Many of the clan having emigrated to Canada about the beginning of the nineteenth century,

and being very successful, 300 of those remaining in Scotland were induced about 1817 to

try their fortunes in America, and in 1821, the chief himself, with some more of the clan,

took their departure for Canada. He returned in 1853, and died at Lannion, Cotes du Nord,

France, Aug 12, 1860, aged 83. He left a window, and one surviving daughter, Sophia

Frances.

The next Macnabs by descent entitled to the chiefship are believed to be Sir Allan Napier

Macnab, Bart, Canada; Dr Robert Macnab, 5th Fusileers; and Mr John Macnab, Glenmavis,

Bathgate.

The lairds of Macnab, previous to the reign of Charles I, intermarried with the families

of Lord Gray of Kilfauns, Gleneagles, Inchbraco, Robertson of Stowan, &c.

The chief cadets of the family were the Macnabs of Dundurn, Acharne, Newton, Cowie, and

Inchewen.

Another Account of the Clan

BADGE: Giuthas (Pinus sylvestris) pine.

PIBROCH: Failte mihic an Abba.

IT

is recorded by Lockhart in his Life of Sir Walter Scott that the

great romancer once confessed that he found it difficult to tell over

again a story which had caught his fancy without "giving it a hat and

stick." Among the stories to which Sir Walter was no doubt wont to

make such additions were more than one which had for their subject the

somewhat fantastic figure of Francis Macnab, chief of that clan, whose

portrait, painted by Raeburn, is one of the most famous achievements of

that great Scottish artist, and who, after a warm-hearted and somewhat

convival career, died at Callander on 25th May, 1816. It was one of these

presumably partly true stories, fathered upon the Chief, which Scott was

on one occasion telling at the breakfast table at Abbotsford when his

wife, who did not always understand the point of the narrative, looked up

from her coffee pot, and, with an attempt to show herself interested in

the matter in hand, exclaimed "And is Macnab dead?" Struck of a

heap by the innocent ineptitude of the remark, Scott, says Lockhart,

looked quizzically at his wife, and with a smile replied, "Well, my

dear, if he isn’t dead they’ve done him a grave injustice, for they’ve

buried him." IT

is recorded by Lockhart in his Life of Sir Walter Scott that the

great romancer once confessed that he found it difficult to tell over

again a story which had caught his fancy without "giving it a hat and

stick." Among the stories to which Sir Walter was no doubt wont to

make such additions were more than one which had for their subject the

somewhat fantastic figure of Francis Macnab, chief of that clan, whose

portrait, painted by Raeburn, is one of the most famous achievements of

that great Scottish artist, and who, after a warm-hearted and somewhat

convival career, died at Callander on 25th May, 1816. It was one of these

presumably partly true stories, fathered upon the Chief, which Scott was

on one occasion telling at the breakfast table at Abbotsford when his

wife, who did not always understand the point of the narrative, looked up

from her coffee pot, and, with an attempt to show herself interested in

the matter in hand, exclaimed "And is Macnab dead?" Struck of a

heap by the innocent ineptitude of the remark, Scott, says Lockhart,

looked quizzically at his wife, and with a smile replied, "Well, my

dear, if he isn’t dead they’ve done him a grave injustice, for they’ve

buried him."

Another story of Macnab, told by Sir

Walter, this time in print, had probably truth behind it, for it was in

full agreement with the humour and shortcomings of the Chief. The latter,

it is said, was somewhat in the habit of forgetting to pay all his

outstanding debts before he left Edinburgh for his Highland residence at

the western end of Loch Tay, and on one occasion a creditor had the

temerity to send a Sheriff’s officer into the Highlands to collect the

account. Macnab, who saw the messenger arrive at Kinnell, at once guessed

his errand. With great show of Highland hospitality he made the man

welcome, and would not allow any talk of business that night. In the

morning, when the messenger awoke and looked from his bedroom window, he

was horrified to see the figure of a man suspended from the branch of a

tree in front of the house. Making his way downstairs, he enquired of a

servant the meaning of the fearful sight, and was answered by the

man casually that it was "Just a bit tam messenger body that had the

presumption to bring a bit o’ paper frae Edinburgh to ta Laird."

Needless to say, when breakfast time came the Sheriff’s officer was

nowhere to be found.

Many other stories not told by Sir Walter

Scott, were wont to be fathered upon the picturesque figure of the Macnab

Chief. One of these may be enough to show their character.

On one occasion, it is said,

Macnab paid a

visit to the new Saracen Head Inn in Glasgow, and, on being shown to his

room for the night, found himself confronted with a great four-poster bed,

a contrivance with which he had not hitherto made acquaintance. Looking at

it for a moment he said to his man, "Donald, you go in there,"

pointing to the bed itself; "the Macnab must go aloft." And with

his man’s help he made his way to the higher place on the canopy. After

an hour or two, it is said, he addressed his henchman. "Donald,"

he whispered; but the only reply was a snore from the happy individual

ensconced upon the feathers below. " Donald, ye rascal," he

repeated, and, having at last secured his man’s attention, enquired,

"Are ye comfortable doun there?" Donald declared that he was

comfortable, whereupon Macnab is said to have rejoined, "Man, if it

werena for the honour of the thing I think I would come doun beside

ye!"

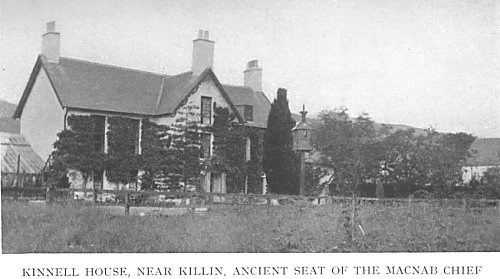

The little old mansion-house of Kinnell, in

which Francis, Chief of Macnab, entertained his friends not wisely but too

well, still stands in the pleasant meadows on the ban of the Dochart

opposite Killin, not far from the spot where that river enters Loch Tay.

It is now a possession of the Earl of Breadalbane, but it still contains

many curious and interesting pieces of antique furniture and other

household plenishing which belonged to the old chiefs of the clan. Among

these, in the little old low-roofed dining-room, which has seen many a

revel in days gone by, remains the quaint gate-legged oak table with

folding wings and drawers, the little low sideboard, black with age, with

spindle legs and brass mountings, the corner cupboard with carved doors,

the fine old writing bureau with folding top and drawers underneath, and

the antique "wag at the wa’ " clock still ticking away the

time, between the two windows, which witnessed the hospitalities of the

redoubtable Laird of Macnab himself. Among minor relics in a case in the

drawing-room are his watch, dated 1787, his stuff-box, seal, spectacles,

and shoe buckles, while above the dining-room door are some pewter flagons

bearing the inscriptions, probably carved on them by some guest:

Here’s beef on the board

And there’s troot on the slab,

Here’s welcome for a’

And a health to Macnab.

and

For warlocks and bogies

We’re nae carin’ a dab,

Syne safe for the night

‘Neath the roof o’ Macnab.

Besides old toddy ladles of horn and

silver, great cut-glass decanters, silver quaichs, and pewter salvers, and

a set of rare old round-bowled pewter spoons, some or all of which were

Macnab possessions, there is the Kinnell Bottle bearing the following

inscription: " It is stated the Laird had a bottle that held nine

gallons (nine bottles?) which was the joy of his friends. This holds nine

bottles, the gift of a friend." The late Laird of Kinnell, the

Marquess of Breadalbane, took great pains to collect and retain within the

walls of the little old mansion as many relics as possible of its bygone

owners, and amid such suggestive relics as "the long gun" of the

Macnabs, a primitive weapon of prodigious length and weight; the old

Kinnell basting-spoon, known as Francis’s Porridge Spoon—long enough

to be used for supping with a certain personage; and the actual brass

candlestick which belonged to the terrible Smooth John Macnab presently to

be mentioned, it is not difficult to picture the life which was led here

in the valley of the Dochart by the old lairds of Macnab and their

households.

Kinnell

is famous to-day for another possession, nothing less than the largest

vine in the world. This is a black Hamburg of excellent quality, half as

large again as that at Hampton Court. It has occupied its present position

since 1837, and is capable of yielding a thousand bunches of grapes in the

year, each weighing a pound and a half, though it is never allowed to

ripen more than half that number. Kinnell

is famous to-day for another possession, nothing less than the largest

vine in the world. This is a black Hamburg of excellent quality, half as

large again as that at Hampton Court. It has occupied its present position

since 1837, and is capable of yielding a thousand bunches of grapes in the

year, each weighing a pound and a half, though it is never allowed to

ripen more than half that number.

Kinnell House of the

present day, however, is not the original seat of the Macnab Chief. This

was situated some hundreds of yards nearer the loch than the present

mansion-house, and though no traces of it now exist, the spot is

associated with not a few incidents which remain among the most dramatic

and characteristic in Highland history.

Most famous of these

incidents is that which terminated the feud of the Macnabs with Clan Neish,

whose head-quarters were at St. Fillans on Lochearnside, some twelve miles

away. The two clans had fought out their feud in a great battle in Glen

Boltachan, above St. Fillans. In that battle the Neishes had been all but

wiped out, and the remnant of them, retiring to the only island in

Lochearn, took to a life of plunder, and secured themselves from reprisals

by allowing no boats but their own on the loch. After a time, however,

encouraged by immunity, they went so far as to plunder the messenger of

Macnab himself, as he returned on one occasion from Crieff with the Chief’s

Christmas fare. On news of the affront reaching Kinnell, Macnab became red

with wrath. Striding into the room where his twelve sons sat, he told them

of what had occurred, and ended his harangue with the significant hint,

"The night is the night, if the lads were the lads." At that, it

is said, the twelve got up, filed out, and, headed by Smooth John, so

called because he was the biggest and brawniest of the household,

proceeded to vindicate the honour of their name. Taking a boat from Loch

Tay, they carried it in relays across the hills and launched it on Loch

Earn. When they reached the island fastness of their enemies in the middle

of the night, all were asleep but old Neish himself, who called out in

alarm to know who was there. "Whom do you least wish to see?"

was the answer, to which he replied, "There is no one I would fear if

it were not Smooth John Macnab." "And Smooth John it is,"

returned that brawny individual, as he drove in the door. Next morning, as

the twelve young men filed into their father’s presence at Kinnell,

Smooth John set the head of the Neish Chief on the table with the words,

"The night was the night, and the lads were the lads." At that,

it is said, old Macnab looked up and answered only "Dread nought!"

And from that hour the Neish’s head has remained the cognisance and

"Dread nought" the motto of the Macnab Clan. A number of years

ago, as if to corroborate the details of this narrative, the fragments of

a boat were found far up on the hills between Loch Tay and Loch Earn,

where it may be supposed Smooth John and his brothers had grown tired of

carrying it, and abandoned their craft.

Many other warlike incidents are narrated

of the clan. It has been claimed that the race were originally MacDonalds;

but from its location and other facts it seems now to be admitted that the

clan was a branch of the Siol Alpin, of which the MacGregors were the main

stem. From the earliest time the chiefs possessed extensive lands in the

lower part of Glendochart, at the western end of Loch Tay. A son of the

chief who flourished during the reign of David I. in the twelfth century,

was abbot or prior of Glendochart, and from him the race took its

subsequent name of Mac an Abba, or Macnab, "the son of the

abbot." At the beginning of the fourteenth century, however, the

Macnab Chief took part with his powerful neighbour, the Lord of Lorne, on

the side of the Baliols and Comyns, and against King Robert the Bruce. The

king’s historian, John Barbour, records that Bruce’s brother-in-law,

Sir Christopher Seton, was betrayed to the English and a fearful death by

his confidant and familiar friend Macnab, and it is said the Macnabs

particularly distinguished themselves in the famous fight at Dal Righ,

near Tyndrum, at the western end of Glendochart, in which John of Lorne

nearly succeeded in cutting off and capturing Bruce himself. For this they

came under Bruce’s extreme displeasure, with the result that they lost a

large part of their possessions. The principal messuage of the lands which

remained to them was known as the Bowlain, and for this the chief received

a crown charter from David II. in 1336. This charter was renewed with

additions in 1486, 1502, and at other dates.

Already, however, in the fifteenth century,

the Macnabs had begun to suffer from the schemes and encroachments of the

great house of Campbell, which was then extending its possessions in all

directions from its original stronghold of Inch Connell amid the waters of

Loch Awe. Among other enterprises the Macnabs were instigated by Campbell

of Loch Awe to attack their own kinsman, the MacGregors. The upshot was a

stiff fight near Crianlarich, in which the Macnabs were almost

exterminated. After the fight, when both clans were considerably weakened,

the Knight of Lochow proceeded to vindicate the law upon both of them, not

without considerable advantage to himself.

In 1645, when the Marquess of Montrose

raised the standard of Charles I. in Scotland, he was joined by the Chief

of Macnab, who, with his clansmen, fought bravely in Montrose’s crowning

victory at Kilsyth. He was then appointed to garrison Montrose’s own

castle of Kincardine, near Auchterarder in Strathearn. The stronghold,

however, was besieged presently by a Convenanting force under General

Leslie, and Macnab found that it would be impossible to maintain the

defence. Accordingly, in the middle of the night, he sallied forth, sword

in hand, at the head of his three hundred clansmen, when all managed to

cut their way through the beseiging force, except the Chief himself and

one follower. These were made captive and sent to Edinburgh, where Macnab,

though a prisoner of war, was accorded at the hands of Covenanters the

same treatment as they meted out at Newark Castle and elsewhere to the

other adherents of Montrose, who had been captured at the battle of

Philiphaugh. Macnab was condemned to death, but on the night before his

execution he contrived to escape, and afterwards, joining the young King

Charles II., he followed him into England, and fell at the battle of

Worcester in 1651.

Meanwhile his house had been burnt, his

charters destroyed, and his property given to Campbell of Glenurchy,

kinsman of the Marquess of Argyll, then at the head of the Covenanting

party and the Government of Scotland. So reduced was the state of the

house that Macnab’s widow was forced to apply for relief to General

Monk, Cromwell’s plenipotentiary in Scotland. That General ordered

Glenurchy, one of whose chief strongholds was Finlarig Castle, close to

Kinnell on Loch Tay side, to restore the Macnab possessions to the widow

and her son. The order, however, had little effect, and after the

Restoration only a portion of the ancient lands were restored to them by

the Scottish Parliament.

These lands might still have belonged to

the Macnabs but for the extraordinary character and exuberant hospitality

of Francis, the twelfth Chief, already referred to. Two more stories of

this redoubtable personage may be repeated. He was deputed on one occasion

to go to Edinburgh to secure from the military authorities clothing and

accoutrements for the Breadalbane Fencibles, then being raised. The

General in Command ventured to express some doubt as to the existence of

the force, and Macnab proceeded to further his case with the high military

authority by addressing him again and again as "My little man."

Macnab himself, it may be mentioned, was a personage of towering height,

and, with his lofty bonnet, belted plaid, and other appurtenances, made a

truly formidable figure. The Fencibles being raised, he marched them to

Edinburgh, and was much mortified on being stopped by an excise party, who

took them for a party of smugglers carrying a quantity of whisky, of whom

they had received intimation. Macnab, it is said, indignantly refused to

stop, and on the excisemen insisting in the name of His Majesty, the Chief

haughtily replied, "I also am on His Majesty’s service. Halt! This,

my lads, is a serious affair, load—with ball." At this, it is said,

the officers perceived the sort of personage they had to do with, and

prudently gave up their attempt.

By reason of the burdens accumulated on the

estate by the twelfth Chief the greater part of the possessions of the

family passed into the hands of the House of Breadalbane. Then the last

Chief who had his home at Kinnell betook himself to Canada. At a later day

he returned and sold the last of his possessions in this country, the

Dreadnought Hotel in Callander. When he died he bequeathed all his

heirlooms to Sir Allan Macnab, Bart., Prime Minister of Canada, whom he

considered the next Chief. But Sir Allan’s son was killed by a gun

accident when shooting in the Dominion, and since then the chiefship has

been claimed by more than one person. Sir Allan Macnab’s second

daughter, Sophia Mary, married the seventh Earl of Albemarle.

The chief memorial of the old

Macnab family

in Glendochart to-day is their romantic burying-place among the trees on

the rocky islet of Inch Buidhe in the Dochart, a little way above Kinnell.

There, with the Dochart in its rocky bed singing its great old song for

ever around their dust, rest in peace the once fierce beating hearts of

these old descendants of the Abbot of Glendochart and the royal race of

Alpin.

Septs of Clan Macnab: Abbotson, Abbot,

Dewar, Gilfillan, Macandeoir.

Another account of the clan...

The name

Macnab means in Gaelic

"son of the Abbot", hence the name Clann-an-Aba, descendants of the Abbot. The

Macnabs were in fact descendants from the Abbots of Glendochart. The clan possessed lands

on the shores of Loch Tay, in Strathfillan and Glendochart, with their seat at Kinnel.

Unfortunately the Macnabs joined the wrong side against Robert the Bruce and were

forfeited of all their possessions except the lands of Bovain in Glendochart. This area

was later confirmed to them by a charter from David II to Gilbert Macnab in 1336 and hence

the clan was restored. Findlay, 12th chief was father of eleven sons who are reputed to

have slain the Macneishes on their island stronghold and carried the head of the chief

back to their father. Iain, known as "Smooth John of Macnab", was one of the

sons faithful to the Royal cause who died fighting for Charles II at Worcester in 1651.

The Macnabs were dispossesed of their lands by the Campbells but after the Restoration in

1660, when the Campbell chief was executed their property was restored. The last chief,

Francis Macnab, despite inheriting considerable estates and fathering many illegitimate

children, squandered his patrimony and failed to produce an heir. He was succeeded by his

nephew, Archibald who ran up debts so great that he had to flee to Canada, deserting his

wife and family. There, despite his past he managed to establish the Macnabs under a

feudal clan system. Eventually he was convicted and returned to Scotland in 1853. The chiefship lay dormant untill it was confirmed on Archibald

Macnab of Arthurstone, 22nd

chief in 1955 who had repurchased Kinnel the seat of the Clan Macnab in 1949. |